|

|

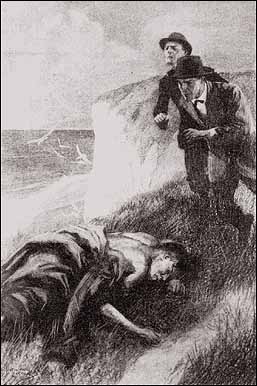

My companion was paralyzed by the sudden horror of it, but I,

as may well be imagined, had every sense on the alert. And I had need, for it was speedily

evident that we were in the presence of an extraordinary case. The man was dressed only in

his Burberry overcoat, his trousers, and an unlaced pair of canvas shoes. As he fell over,

his Burberry, which had been simply thrown round his shoulders, slipped off, exposing his

trunk. We stared at it in amazement. His back was covered with dark red lines as though he

had been terribly flogged by a thin wire scourge. The instrument with which this

punishment had been inflicted was clearly flexible, for the long, angry weals curved round

his shoulders and ribs. There was blood dripping down his chin, for he had bitten through

his lower lip in the paroxysm of his agony. His drawn and distorted face told how terrible

that agony had been. My companion was paralyzed by the sudden horror of it, but I,

as may well be imagined, had every sense on the alert. And I had need, for it was speedily

evident that we were in the presence of an extraordinary case. The man was dressed only in

his Burberry overcoat, his trousers, and an unlaced pair of canvas shoes. As he fell over,

his Burberry, which had been simply thrown round his shoulders, slipped off, exposing his

trunk. We stared at it in amazement. His back was covered with dark red lines as though he

had been terribly flogged by a thin wire scourge. The instrument with which this

punishment had been inflicted was clearly flexible, for the long, angry weals curved round

his shoulders and ribs. There was blood dripping down his chin, for he had bitten through

his lower lip in the paroxysm of his agony. His drawn and distorted face told how terrible

that agony had been.

I was kneeling and Stackhurst standing by the body when a

shadow fell across us, and we found that Ian Murdoch was by our side. Murdoch was the

mathematical coach at the establishment, a tall, dark, thin man, so taciturn and aloof

that none can be said to have been his friend. He seemed to live in some high, abstract

region of surds and conic sections, with little to connect him with ordinary life. He was

looked upon as an oddity by the students, and would have been their butt, but there was

some strange outlandish blood in the man, which showed itself not only in his coal-black

eyes and swarthy face but also in occasional outbreaks of temper, which could only be

described as ferocious. On one occasion, being plagued by a little dog belonging to

McPherson, he had caught the creature up and hurled it through the plate-glass window, an

action for which Stackhurst would certainly have given him his dismissal had he not been a

very valuable teacher. Such was the strange complex man who now appeared beside us. He

seemed to be [1085] honestly

shocked at the sight before him, though the incident of the dog may show that there was no

great sympathy between the dead man and himself. I was kneeling and Stackhurst standing by the body when a

shadow fell across us, and we found that Ian Murdoch was by our side. Murdoch was the

mathematical coach at the establishment, a tall, dark, thin man, so taciturn and aloof

that none can be said to have been his friend. He seemed to live in some high, abstract

region of surds and conic sections, with little to connect him with ordinary life. He was

looked upon as an oddity by the students, and would have been their butt, but there was

some strange outlandish blood in the man, which showed itself not only in his coal-black

eyes and swarthy face but also in occasional outbreaks of temper, which could only be

described as ferocious. On one occasion, being plagued by a little dog belonging to

McPherson, he had caught the creature up and hurled it through the plate-glass window, an

action for which Stackhurst would certainly have given him his dismissal had he not been a

very valuable teacher. Such was the strange complex man who now appeared beside us. He

seemed to be [1085] honestly

shocked at the sight before him, though the incident of the dog may show that there was no

great sympathy between the dead man and himself.

“Poor fellow! Poor fellow! What can I do? How can I

help?” “Poor fellow! Poor fellow! What can I do? How can I

help?”

“Were you with him? Can you tell us what has

happened?” “Were you with him? Can you tell us what has

happened?”

“No, no, I was late this morning. I was not on the beach

at all. I have come straight from The Gables. What can I do?” “No, no, I was late this morning. I was not on the beach

at all. I have come straight from The Gables. What can I do?”

“You can hurry to the police-station at Fulworth. Report

the matter at once.” “You can hurry to the police-station at Fulworth. Report

the matter at once.”

Without a word he made off at top speed, and I proceeded to

take the matter in hand, while Stackhurst, dazed at this tragedy, remained by the body. My

first task naturally was to note who was on the beach. From the top of the path I could

see the whole sweep of it, and it was absolutely deserted save that two or three dark

figures could be seen far away moving towards the village of Fulworth. Having satisfied

myself upon this point, I walked slowly down the path. There was clay or soft marl mixed

with the chalk, and every here and there I saw the same footstep, both ascending and

descending. No one else had gone down to the beach by this track that morning. At one

place I observed the print of an open hand with the fingers towards the incline. This

could only mean that poor McPherson had fallen as he ascended. There were rounded

depressions, too, which suggested that he had come down upon his knees more than once. At

the bottom of the path was the considerable lagoon left by the retreating tide. At the

side of it McPherson had undressed, for there lay his towel on a rock. It was folded and

dry, so that it would seem that, after all, he had never entered the water. Once or twice

as I hunted round amid the hard shingle I came on little patches of sand where the print

of his canvas shoe, and also of his naked foot, could be seen. The latter fact proved that

he had made all ready to bathe, though the towel indicated that he had not actually done

so. Without a word he made off at top speed, and I proceeded to

take the matter in hand, while Stackhurst, dazed at this tragedy, remained by the body. My

first task naturally was to note who was on the beach. From the top of the path I could

see the whole sweep of it, and it was absolutely deserted save that two or three dark

figures could be seen far away moving towards the village of Fulworth. Having satisfied

myself upon this point, I walked slowly down the path. There was clay or soft marl mixed

with the chalk, and every here and there I saw the same footstep, both ascending and

descending. No one else had gone down to the beach by this track that morning. At one

place I observed the print of an open hand with the fingers towards the incline. This

could only mean that poor McPherson had fallen as he ascended. There were rounded

depressions, too, which suggested that he had come down upon his knees more than once. At

the bottom of the path was the considerable lagoon left by the retreating tide. At the

side of it McPherson had undressed, for there lay his towel on a rock. It was folded and

dry, so that it would seem that, after all, he had never entered the water. Once or twice

as I hunted round amid the hard shingle I came on little patches of sand where the print

of his canvas shoe, and also of his naked foot, could be seen. The latter fact proved that

he had made all ready to bathe, though the towel indicated that he had not actually done

so.

And here was the problem clearly defined–as strange a one

as had ever confronted me. The man had not been on the beach more than a quarter of an

hour at the most. Stackhurst had followed him from The Gables, so there could be no doubt

about that. He had gone to bathe and had stripped, as the naked footsteps showed. Then he

had suddenly huddled on his clothes again–they were all dishevelled and

unfastened–and he had returned without bathing, or at any rate without drying

himself. And the reason for his change of purpose had been that he had been scourged in

some savage, inhuman fashion, tortured until he bit his lip through in his agony, and was

left with only strength enough to crawl away and to die. Who had done this barbarous deed?

There were, it is true, small grottos and caves in the base of the cliffs, but the low sun

shone directly into them, and there was no place for concealment. Then, again, there were

those distant figures on the beach. They seemed too far away to have been connected with

the crime, and the broad lagoon in which McPherson had intended to bathe lay between him

and them, lapping up to the rocks. On the sea two or three fishing-boats were at no great

distance. Their occupants might be examined at our leisure. There were several roads for

inquiry, but none which led to any very obvious goal. And here was the problem clearly defined–as strange a one

as had ever confronted me. The man had not been on the beach more than a quarter of an

hour at the most. Stackhurst had followed him from The Gables, so there could be no doubt

about that. He had gone to bathe and had stripped, as the naked footsteps showed. Then he

had suddenly huddled on his clothes again–they were all dishevelled and

unfastened–and he had returned without bathing, or at any rate without drying

himself. And the reason for his change of purpose had been that he had been scourged in

some savage, inhuman fashion, tortured until he bit his lip through in his agony, and was

left with only strength enough to crawl away and to die. Who had done this barbarous deed?

There were, it is true, small grottos and caves in the base of the cliffs, but the low sun

shone directly into them, and there was no place for concealment. Then, again, there were

those distant figures on the beach. They seemed too far away to have been connected with

the crime, and the broad lagoon in which McPherson had intended to bathe lay between him

and them, lapping up to the rocks. On the sea two or three fishing-boats were at no great

distance. Their occupants might be examined at our leisure. There were several roads for

inquiry, but none which led to any very obvious goal.

When I at last returned to the body I found that a little

group of wondering folk had gathered round it. Stackhurst was, of course, still there, and

Ian Murdoch had just arrived with Anderson, the village constable, a big,

ginger-moustached man of the slow, solid Sussex breed–a breed which covers much good

sense under a heavy, silent exterior. He listened to everything, took note of all we said,

and finally drew me aside. When I at last returned to the body I found that a little

group of wondering folk had gathered round it. Stackhurst was, of course, still there, and

Ian Murdoch had just arrived with Anderson, the village constable, a big,

ginger-moustached man of the slow, solid Sussex breed–a breed which covers much good

sense under a heavy, silent exterior. He listened to everything, took note of all we said,

and finally drew me aside.

[1086] “I’d

be glad of your advice, Mr. Holmes. This is a big thing for me to handle, and I’ll

hear of it from Lewes if I go wrong.” [1086] “I’d

be glad of your advice, Mr. Holmes. This is a big thing for me to handle, and I’ll

hear of it from Lewes if I go wrong.”

I advised him to send for his immediate superior, and for a

doctor; also to allow nothing to be moved, and as few fresh footmarks as possible to be

made, until they came. In the meantime I searched the dead man’s pockets. There were

his handkerchief, a large knife, and a small folding card-case. From this projected a slip

of paper, which I unfolded and handed to the constable. There was written on it in a

scrawling, feminine hand: I advised him to send for his immediate superior, and for a

doctor; also to allow nothing to be moved, and as few fresh footmarks as possible to be

made, until they came. In the meantime I searched the dead man’s pockets. There were

his handkerchief, a large knife, and a small folding card-case. From this projected a slip

of paper, which I unfolded and handed to the constable. There was written on it in a

scrawling, feminine hand:

- I will be there, you may be sure.

- MAUDIE.

It read like a love affair, an assignation, though when and where were a blank. The

constable replaced it in the card-case and returned it with the other things to the

pockets of the Burberry. Then, as nothing more suggested itself, I walked back to my house

for breakfast, having first arranged that the base of the cliffs should be thoroughly

searched.

Stackhurst was round in an hour or two to tell me that the

body had been removed to The Gables, where the inquest would be held. He brought with him

some serious and definite news. As I expected, nothing had been found in the small caves

below the cliff, but he had examined the papers in McPherson’s desk, and there were

several which showed an intimate correspondence with a certain Miss Maud Bellamy, of

Fulworth. We had then established the identity of the writer of the note. Stackhurst was round in an hour or two to tell me that the

body had been removed to The Gables, where the inquest would be held. He brought with him

some serious and definite news. As I expected, nothing had been found in the small caves

below the cliff, but he had examined the papers in McPherson’s desk, and there were

several which showed an intimate correspondence with a certain Miss Maud Bellamy, of

Fulworth. We had then established the identity of the writer of the note.

“The police have the letters,” he explained. “I

could not bring them. But there is no doubt that it was a serious love affair. I see no

reason, however, to connect it with that horrible happening save, indeed, that the lady

had made an appointment with him.” “The police have the letters,” he explained. “I

could not bring them. But there is no doubt that it was a serious love affair. I see no

reason, however, to connect it with that horrible happening save, indeed, that the lady

had made an appointment with him.”

“But hardly at a bathing-pool which all of you were in

the habit of using,” I remarked. “But hardly at a bathing-pool which all of you were in

the habit of using,” I remarked.

“It is mere chance,” said he, “that several of

the students were not with McPherson.” “It is mere chance,” said he, “that several of

the students were not with McPherson.”

“Was it mere chance?” “Was it mere chance?”

Stackhurst knit his brows in thought. Stackhurst knit his brows in thought.

“Ian Murdoch held them back,” said he. “He

would insist upon some algebraic demonstration before breakfast. Poor chap, he is

dreadfully cut up about it all.” “Ian Murdoch held them back,” said he. “He

would insist upon some algebraic demonstration before breakfast. Poor chap, he is

dreadfully cut up about it all.”

“And yet I gather that they were not friends.” “And yet I gather that they were not friends.”

“At one time they were not. But for a year or more

Murdoch has been as near to McPherson as he ever could be to anyone. He is not of a very

sympathetic disposition by nature.” “At one time they were not. But for a year or more

Murdoch has been as near to McPherson as he ever could be to anyone. He is not of a very

sympathetic disposition by nature.”

“So I understand. I seem to remember your telling me once

about a quarrel over the ill-usage of a dog.” “So I understand. I seem to remember your telling me once

about a quarrel over the ill-usage of a dog.”

“That blew over all right.” “That blew over all right.”

“But left some vindictive feeling, perhaps.” “But left some vindictive feeling, perhaps.”

“No, no, I am sure they were real friends.” “No, no, I am sure they were real friends.”

“Well, then, we must explore the matter of the girl. Do

you know her?” “Well, then, we must explore the matter of the girl. Do

you know her?”

“Everyone knows her. She is the beauty of the

neighbourhood–a real beauty, Holmes, who would draw attention everywhere. I knew that

McPherson was attracted by her, but I had no notion that it had gone so far as these

letters would seem to indicate.” “Everyone knows her. She is the beauty of the

neighbourhood–a real beauty, Holmes, who would draw attention everywhere. I knew that

McPherson was attracted by her, but I had no notion that it had gone so far as these

letters would seem to indicate.”

[1087] “But

who is she?” [1087] “But

who is she?”

“She is the daughter of old Tom Bellamy, who owns all the

boats and bathing-cots at Fulworth. He was a fisherman to start with, but is now a man of

some substance. He and his son William run the business.” “She is the daughter of old Tom Bellamy, who owns all the

boats and bathing-cots at Fulworth. He was a fisherman to start with, but is now a man of

some substance. He and his son William run the business.”

“Shall we walk into Fulworth and see them?” “Shall we walk into Fulworth and see them?”

“On what pretext?” “On what pretext?”

“Oh, we can easily find a pretext. After all, this poor

man did not ill-use himself in this outrageous way. Some human hand was on the handle of

that scourge, if indeed it was a scourge which inflicted the injuries. His circle of

acquaintances in this lonely place was surely limited. Let us follow it up in every

direction and we can hardly fail to come upon the motive, which in turn should lead us to

the criminal.” “Oh, we can easily find a pretext. After all, this poor

man did not ill-use himself in this outrageous way. Some human hand was on the handle of

that scourge, if indeed it was a scourge which inflicted the injuries. His circle of

acquaintances in this lonely place was surely limited. Let us follow it up in every

direction and we can hardly fail to come upon the motive, which in turn should lead us to

the criminal.”

It would have been a pleasant walk across the thyme-scented

downs had our minds not been poisoned by the tragedy we had witnessed. The village of

Fulworth lies in a hollow curving in a semicircle round the bay. Behind the old-fashioned

hamlet several modern houses have been built upon the rising ground. It was to one of

these that Stackhurst guided me. It would have been a pleasant walk across the thyme-scented

downs had our minds not been poisoned by the tragedy we had witnessed. The village of

Fulworth lies in a hollow curving in a semicircle round the bay. Behind the old-fashioned

hamlet several modern houses have been built upon the rising ground. It was to one of

these that Stackhurst guided me.

“That’s The Haven, as Bellamy called it. The one

with the corner tower and slate roof. Not bad for a man who started with nothing but–

– By Jove, look at that!” “That’s The Haven, as Bellamy called it. The one

with the corner tower and slate roof. Not bad for a man who started with nothing but–

– By Jove, look at that!”

The garden gate of The Haven had opened and a man had emerged.

There was no mistaking that tall, angular, straggling figure. It was Ian Murdoch, the

mathematician. A moment later we confronted him upon the road. The garden gate of The Haven had opened and a man had emerged.

There was no mistaking that tall, angular, straggling figure. It was Ian Murdoch, the

mathematician. A moment later we confronted him upon the road.

“Hullo!” said Stackhurst. The man nodded, gave us a

sideways glance from his curious dark eyes, and would have passed us, but his principal

pulled him up. “Hullo!” said Stackhurst. The man nodded, gave us a

sideways glance from his curious dark eyes, and would have passed us, but his principal

pulled him up.

“What were you doing there?” he asked. “What were you doing there?” he asked.

Murdoch’s face flushed with anger. “I am your

subordinate, sir, under your roof. I am not aware that I owe you any account of my private

actions.” Murdoch’s face flushed with anger. “I am your

subordinate, sir, under your roof. I am not aware that I owe you any account of my private

actions.”

Stackhurst’s nerves were near the surface after all he

had endured. Otherwise, perhaps, he would have waited. Now he lost his temper completely. Stackhurst’s nerves were near the surface after all he

had endured. Otherwise, perhaps, he would have waited. Now he lost his temper completely.

“In the circumstances your answer is pure impertinence,

Mr. Murdoch.” “In the circumstances your answer is pure impertinence,

Mr. Murdoch.”

“Your own question might perhaps come under the same

heading.” “Your own question might perhaps come under the same

heading.”

“This is not the first time that I have had to overlook

your insubordinate ways. It will certainly be the last. You will kindly make fresh

arrangements for your future as speedily as you can.” “This is not the first time that I have had to overlook

your insubordinate ways. It will certainly be the last. You will kindly make fresh

arrangements for your future as speedily as you can.”

“I had intended to do so. I have lost to-day the only

person who made The Gables habitable.” “I had intended to do so. I have lost to-day the only

person who made The Gables habitable.”

He strode off upon his way, while Stackhurst, with angry eyes,

stood glaring after him. “Is he not an impossible, intolerable man?” he cried. He strode off upon his way, while Stackhurst, with angry eyes,

stood glaring after him. “Is he not an impossible, intolerable man?” he cried.

The one thing that impressed itself forcibly upon my mind was

that Mr. Ian Murdoch was taking the first chance to open a path of escape from the scene

of the crime. Suspicion, vague and nebulous, was now beginning to take outline in my mind.

Perhaps the visit to the Bellamys might throw some further light upon the matter.

Stackhurst pulled himself together, and we went forward to the house. The one thing that impressed itself forcibly upon my mind was

that Mr. Ian Murdoch was taking the first chance to open a path of escape from the scene

of the crime. Suspicion, vague and nebulous, was now beginning to take outline in my mind.

Perhaps the visit to the Bellamys might throw some further light upon the matter.

Stackhurst pulled himself together, and we went forward to the house.

Mr. Bellamy proved to be a middle-aged man with a flaming red

beard. He seemed to be in a very angry mood, and his face was soon as florid as his hair. Mr. Bellamy proved to be a middle-aged man with a flaming red

beard. He seemed to be in a very angry mood, and his face was soon as florid as his hair.

“No, sir, I do not desire any particulars. My son

here”–indicating a powerful young man, with a heavy, sullen face, in the corner

of the sitting-room –“is of one mind with me that Mr. McPherson’s

attentions to Maud were insulting. Yes, sir, [1088]

the word ‘marriage’ was never mentioned, and yet there were letters and

meetings, and a great deal more of which neither of us could approve. She has no mother,

and we are her only guardians. We are determined– –” “No, sir, I do not desire any particulars. My son

here”–indicating a powerful young man, with a heavy, sullen face, in the corner

of the sitting-room –“is of one mind with me that Mr. McPherson’s

attentions to Maud were insulting. Yes, sir, [1088]

the word ‘marriage’ was never mentioned, and yet there were letters and

meetings, and a great deal more of which neither of us could approve. She has no mother,

and we are her only guardians. We are determined– –”

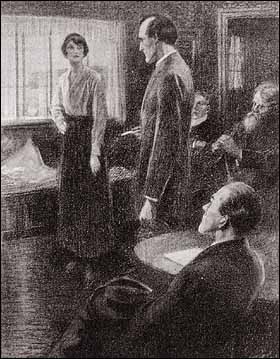

But the words were taken from his mouth by the appearance of

the lady herself. There was no gainsaying that she would have graced any assembly in the

world. Who could have imagined that so rare a flower would grow from such a root and in

such an atmosphere? Women have seldom been an attraction to me, for my brain has always

governed my heart, but I could not look upon her perfect clear-cut face, with all the soft

freshness of the downlands in her delicate colouring, without realizing that no young man

would cross her path unscathed. Such was the girl who had pushed open the door and stood

now, wide-eyed and intense, in front of Harold Stackhurst. But the words were taken from his mouth by the appearance of

the lady herself. There was no gainsaying that she would have graced any assembly in the

world. Who could have imagined that so rare a flower would grow from such a root and in

such an atmosphere? Women have seldom been an attraction to me, for my brain has always

governed my heart, but I could not look upon her perfect clear-cut face, with all the soft

freshness of the downlands in her delicate colouring, without realizing that no young man

would cross her path unscathed. Such was the girl who had pushed open the door and stood

now, wide-eyed and intense, in front of Harold Stackhurst.

“I know already that Fitzroy is dead,” she said.

“Do not be afraid to tell me the particulars.” “I know already that Fitzroy is dead,” she said.

“Do not be afraid to tell me the particulars.”

“This other gentleman of yours let us know the

news,” explained the father. “This other gentleman of yours let us know the

news,” explained the father.

“There is no reason why my sister should be brought into

the matter,” growled the younger man. “There is no reason why my sister should be brought into

the matter,” growled the younger man.

The sister turned a sharp, fierce look upon him. “This is

my business, William. Kindly leave me to manage it in my own way. By all accounts there

has been a crime committed. If I can help to show who did it, it is the least I can do for

him who is gone.” The sister turned a sharp, fierce look upon him. “This is

my business, William. Kindly leave me to manage it in my own way. By all accounts there

has been a crime committed. If I can help to show who did it, it is the least I can do for

him who is gone.”

She listened to a short account from my companion, with a

composed concentration which showed me that she possessed strong character as well as

great beauty. Maud Bellamy will always remain in my memory as a most complete and

remarkable woman. It seems that she already knew me by sight, for she turned to me at the

end. She listened to a short account from my companion, with a

composed concentration which showed me that she possessed strong character as well as

great beauty. Maud Bellamy will always remain in my memory as a most complete and

remarkable woman. It seems that she already knew me by sight, for she turned to me at the

end.

“Bring them to justice, Mr. Holmes. You have my sympathy

and my help, whoever they may be.” It seemed to me that she glanced defiantly at her

father and brother as she spoke. “Bring them to justice, Mr. Holmes. You have my sympathy

and my help, whoever they may be.” It seemed to me that she glanced defiantly at her

father and brother as she spoke.

“Thank you,” said I. “I value a woman’s

instinct in such matters. You use the word ‘they.’ You think that more than one

was concerned?” “Thank you,” said I. “I value a woman’s

instinct in such matters. You use the word ‘they.’ You think that more than one

was concerned?”

“I knew Mr. McPherson well enough to be aware that he was

a brave and a strong man. No single person could ever have inflicted such an outrage upon

him.” “I knew Mr. McPherson well enough to be aware that he was

a brave and a strong man. No single person could ever have inflicted such an outrage upon

him.”

“Might I have one word with you alone?” “Might I have one word with you alone?”

“I tell you, Maud, not to mix yourself up in the

matter,” cried her father angrily. “I tell you, Maud, not to mix yourself up in the

matter,” cried her father angrily.

She looked at me helplessly. “What can I do?” She looked at me helplessly. “What can I do?”

“The whole world will know the facts presently, so there

can be no harm if I discuss them here,” said I. “I should have preferred

privacy, but if your father will not allow it he must share the deliberations.” Then

I spoke of the note which had been found in the dead man’s pocket. “It is sure

to be produced at the inquest. May I ask you to throw any light upon it that you

can?” “The whole world will know the facts presently, so there

can be no harm if I discuss them here,” said I. “I should have preferred

privacy, but if your father will not allow it he must share the deliberations.” Then

I spoke of the note which had been found in the dead man’s pocket. “It is sure

to be produced at the inquest. May I ask you to throw any light upon it that you

can?”

“I see no reason for mystery,” she answered.

“We were engaged to be married, and we only kept it secret because Fitzroy’s

uncle, who is very old and said to be dying, might have disinherited him if he had married

against his wish. There was no other reason.” “I see no reason for mystery,” she answered.

“We were engaged to be married, and we only kept it secret because Fitzroy’s

uncle, who is very old and said to be dying, might have disinherited him if he had married

against his wish. There was no other reason.”

“You could have told us,” growled Mr. Bellamy. “You could have told us,” growled Mr. Bellamy.

“So I would, father, if you had ever shown

sympathy.” “So I would, father, if you had ever shown

sympathy.”

“I object to my girl picking up with men outside her own

station.” “I object to my girl picking up with men outside her own

station.”

[1089] “It

was your prejudice against him which prevented us from telling you. As to this

appointment”–she fumbled in her dress and produced a crumpled note–

“it was in answer to this.” [1089] “It

was your prejudice against him which prevented us from telling you. As to this

appointment”–she fumbled in her dress and produced a crumpled note–

“it was in answer to this.”

- DEAREST [ran the message]:

The old place on the beach just after sunset on Tuesday. It is

the only time I can get away. The old place on the beach just after sunset on Tuesday. It is

the only time I can get away.

- F. M.

“Tuesday was to-day, and I had meant to meet him

to-night.” “Tuesday was to-day, and I had meant to meet him

to-night.”

I turned over the paper. “This never came by post. How

did you get it?” I turned over the paper. “This never came by post. How

did you get it?”

“I would rather not answer that question. It has

really nothing to do with the matter which you are investigating. But anything which bears

upon that I will most freely answer.” “I would rather not answer that question. It has

really nothing to do with the matter which you are investigating. But anything which bears

upon that I will most freely answer.”

She was as good as her word, but there was nothing which was

helpful in our investigation. She had no reason to think that her fiance had any hidden

enemy, but she admitted that she had had several warm admirers. She was as good as her word, but there was nothing which was

helpful in our investigation. She had no reason to think that her fiance had any hidden

enemy, but she admitted that she had had several warm admirers.

“May I ask if Mr. Ian Murdoch was one of them?” “May I ask if Mr. Ian Murdoch was one of them?”

She blushed and seemed confused. She blushed and seemed confused.

“There was a time when I thought he was. But that was all

changed when he understood the relations between Fitzroy and myself.” “There was a time when I thought he was. But that was all

changed when he understood the relations between Fitzroy and myself.”

Again the shadow round this strange man seemed to me to be

taking more definite shape. His record must be examined. His rooms must be privately

searched. Stackhurst was a willing collaborator, for in his mind also suspicions were

forming. We returned from our visit to The Haven with the hope that one free end of this

tangled skein was already in our hands. Again the shadow round this strange man seemed to me to be

taking more definite shape. His record must be examined. His rooms must be privately

searched. Stackhurst was a willing collaborator, for in his mind also suspicions were

forming. We returned from our visit to The Haven with the hope that one free end of this

tangled skein was already in our hands.

A week passed. The inquest had thrown no light upon the matter

and had been adjourned for further evidence. Stackhurst had made discreet inquiry about

his subordinate, and there had been a superficial search of his room, but without result.

Personally, I had gone over the whole ground again, both physically and mentally, but with

no new conclusions. In all my chronicles the reader will find no case which brought me so

completely to the limit of my powers. Even my imagination could conceive no solution to

the mystery. And then there came the incident of the dog. A week passed. The inquest had thrown no light upon the matter

and had been adjourned for further evidence. Stackhurst had made discreet inquiry about

his subordinate, and there had been a superficial search of his room, but without result.

Personally, I had gone over the whole ground again, both physically and mentally, but with

no new conclusions. In all my chronicles the reader will find no case which brought me so

completely to the limit of my powers. Even my imagination could conceive no solution to

the mystery. And then there came the incident of the dog.

It was my old housekeeper who heard of it first by that

strange wireless by which such people collect the news of the countryside. It was my old housekeeper who heard of it first by that

strange wireless by which such people collect the news of the countryside.

“Sad story this, sir, about Mr. McPherson’s

dog,” said she one evening. “Sad story this, sir, about Mr. McPherson’s

dog,” said she one evening.

I do not encourage such conversations, but the words arrested

my attention. I do not encourage such conversations, but the words arrested

my attention.

“What of Mr. McPherson’s dog?” “What of Mr. McPherson’s dog?”

“Dead, sir. Died of grief for its master.” “Dead, sir. Died of grief for its master.”

“Who told you this?” “Who told you this?”

“Why, sir, everyone is talking of it. It took on

terrible, and has eaten nothing for a week. Then to-day two of the young gentlemen from

The Gables found it dead–down on the beach, sir, at the very place where its master

met his end.” “Why, sir, everyone is talking of it. It took on

terrible, and has eaten nothing for a week. Then to-day two of the young gentlemen from

The Gables found it dead–down on the beach, sir, at the very place where its master

met his end.”

“At the very place.” The words stood out clear in my

memory. Some dim perception that the matter was vital rose in my mind. That the dog should

die was after the beautiful, faithful nature of dogs. But “in the very place”!

Why should this lonely beach be fatal to it? Was it possible that it also had been

sacrificed to some revengeful feud? Was it possible– –? Yes, the perception was

dim, but already something was building up in my mind. In a few minutes I was on my way [1090] to The Gables, where I found

Stackhurst in his study. At my request he sent for Sudbury and Blount, the two students

who had found the dog. “At the very place.” The words stood out clear in my

memory. Some dim perception that the matter was vital rose in my mind. That the dog should

die was after the beautiful, faithful nature of dogs. But “in the very place”!

Why should this lonely beach be fatal to it? Was it possible that it also had been

sacrificed to some revengeful feud? Was it possible– –? Yes, the perception was

dim, but already something was building up in my mind. In a few minutes I was on my way [1090] to The Gables, where I found

Stackhurst in his study. At my request he sent for Sudbury and Blount, the two students

who had found the dog.

“Yes, it lay on the very edge of the pool,” said one

of them. “It must have followed the trail of its dead master.” “Yes, it lay on the very edge of the pool,” said one

of them. “It must have followed the trail of its dead master.”

I saw the faithful little creature, an Airedale terrier, laid

out upon the mat in the hall. The body was stiff and rigid, the eyes projecting, and the

limbs contorted. There was agony in every line of it. I saw the faithful little creature, an Airedale terrier, laid

out upon the mat in the hall. The body was stiff and rigid, the eyes projecting, and the

limbs contorted. There was agony in every line of it.

From The Gables I walked down to the bathing-pool. The sun had

sunk and the shadow of the great cliff lay black across the water, which glimmered dully

like a sheet of lead. The place was deserted and there was no sign of life save for two

sea-birds circling and screaming overhead. In the fading light I could dimly make out the

little dog’s spoor upon the sand round the very rock on which his master’s towel

had been laid. For a long time I stood in deep meditation while the shadows grew darker

around me. My mind was filled with racing thoughts. You have known what it was to be in a

nightmare in which you feel that there is some all-important thing for which you search

and which you know is there, though it remains forever just beyond your reach. That was

how I felt that evening as I stood alone by that place of death. Then at last I turned and

walked slowly homeward. From The Gables I walked down to the bathing-pool. The sun had

sunk and the shadow of the great cliff lay black across the water, which glimmered dully

like a sheet of lead. The place was deserted and there was no sign of life save for two

sea-birds circling and screaming overhead. In the fading light I could dimly make out the

little dog’s spoor upon the sand round the very rock on which his master’s towel

had been laid. For a long time I stood in deep meditation while the shadows grew darker

around me. My mind was filled with racing thoughts. You have known what it was to be in a

nightmare in which you feel that there is some all-important thing for which you search

and which you know is there, though it remains forever just beyond your reach. That was

how I felt that evening as I stood alone by that place of death. Then at last I turned and

walked slowly homeward.

I had just reached the top of the path when it came to me.

Like a flash, I remembered the thing for which I had so eagerly and vainly grasped. You

will know, or Watson has written in vain, that I hold a vast store of out-of-the-way

knowledge without scientific system, but very available for the needs of my work. My mind

is like a crowded box-room with packets of all sorts stowed away therein–so many that

I may well have but a vague perception of what was there. I had known that there was

something which might bear upon this matter. It was still vague, but at least I knew how I

could make it clear. It was monstrous, incredible, and yet it was always a possibility. I

would test it to the full. I had just reached the top of the path when it came to me.

Like a flash, I remembered the thing for which I had so eagerly and vainly grasped. You

will know, or Watson has written in vain, that I hold a vast store of out-of-the-way

knowledge without scientific system, but very available for the needs of my work. My mind

is like a crowded box-room with packets of all sorts stowed away therein–so many that

I may well have but a vague perception of what was there. I had known that there was

something which might bear upon this matter. It was still vague, but at least I knew how I

could make it clear. It was monstrous, incredible, and yet it was always a possibility. I

would test it to the full.

There is a great garret in my little house which is stuffed

with books. It was into this that I plunged and rummaged for an hour. At the end of that

time I emerged with a little chocolate and silver volume. Eagerly I turned up the chapter

of which I had a dim remembrance. Yes, it was indeed a far-fetched and unlikely

proposition, and yet I could not be at rest until I had made sure if it might, indeed, be

so. It was late when I retired, with my mind eagerly awaiting the work of the morrow. There is a great garret in my little house which is stuffed

with books. It was into this that I plunged and rummaged for an hour. At the end of that

time I emerged with a little chocolate and silver volume. Eagerly I turned up the chapter

of which I had a dim remembrance. Yes, it was indeed a far-fetched and unlikely

proposition, and yet I could not be at rest until I had made sure if it might, indeed, be

so. It was late when I retired, with my mind eagerly awaiting the work of the morrow.

But that work met with an annoying interruption. I had hardly

swallowed my early cup of tea and was starting for the beach when I had a call from

Inspector Bardle of the Sussex Constabulary–a steady, solid, bovine man with

thoughtful eyes, which looked at me now with a very troubled expression. But that work met with an annoying interruption. I had hardly

swallowed my early cup of tea and was starting for the beach when I had a call from

Inspector Bardle of the Sussex Constabulary–a steady, solid, bovine man with

thoughtful eyes, which looked at me now with a very troubled expression.

“I know your immense experience, sir,” said he.

“This is quite unofficial, of course, and need go no farther. But I am fairly up

against it in this McPherson case. The question is, shall I make an arrest, or shall I

not?” “I know your immense experience, sir,” said he.

“This is quite unofficial, of course, and need go no farther. But I am fairly up

against it in this McPherson case. The question is, shall I make an arrest, or shall I

not?”

“Meaning Mr. Ian Murdoch?” “Meaning Mr. Ian Murdoch?”

“Yes, sir. There is really no one else when you come to

think of it. That’s the advantage of this solitude. We narrow it down to a very small

compass. If he did not do it, then who did?” “Yes, sir. There is really no one else when you come to

think of it. That’s the advantage of this solitude. We narrow it down to a very small

compass. If he did not do it, then who did?”

“What have you against him?” “What have you against him?”

He had gleaned along the same furrows as I had. There was

Murdoch’s character and the mystery which seemed to hang round the man. His furious

bursts of temper, [1091] as

shown in the incident of the dog. The fact that he had quarrelled with McPherson in the

past, and that there was some reason to think that he might have resented his attentions

to Miss Bellamy. He had all my points, but no fresh ones, save that Murdoch seemed to be

making every preparation for departure. He had gleaned along the same furrows as I had. There was

Murdoch’s character and the mystery which seemed to hang round the man. His furious

bursts of temper, [1091] as

shown in the incident of the dog. The fact that he had quarrelled with McPherson in the

past, and that there was some reason to think that he might have resented his attentions

to Miss Bellamy. He had all my points, but no fresh ones, save that Murdoch seemed to be

making every preparation for departure.

“What would my position be if I let him slip away with

all this evidence against him?” The burly, phlegmatic man was sorely troubled in his

mind. “What would my position be if I let him slip away with

all this evidence against him?” The burly, phlegmatic man was sorely troubled in his

mind.

“Consider,” I said, “all the essential gaps in

your case. On the morning of the crime he can surely prove an alibi. He had been with his

scholars till the last moment, and within a few minutes of McPherson’s appearance he

came upon us from behind. Then bear in mind the absolute impossibility that he could

single-handed have inflicted this outrage upon a man quite as strong as himself. Finally,

there is this question of the instrument with which these injuries were inflicted.” “Consider,” I said, “all the essential gaps in

your case. On the morning of the crime he can surely prove an alibi. He had been with his

scholars till the last moment, and within a few minutes of McPherson’s appearance he

came upon us from behind. Then bear in mind the absolute impossibility that he could

single-handed have inflicted this outrage upon a man quite as strong as himself. Finally,

there is this question of the instrument with which these injuries were inflicted.”

“What could it be but a scourge or flexible whip of some

sort?” “What could it be but a scourge or flexible whip of some

sort?”

“Have you examined the marks?” I asked. “Have you examined the marks?” I asked.

“I have seen them. So has the doctor.” “I have seen them. So has the doctor.”

“But I have examined them very carefully with a lens.

They have peculiarities.” “But I have examined them very carefully with a lens.

They have peculiarities.”

“What are they, Mr. Holmes?” “What are they, Mr. Holmes?”

I stepped to my bureau and brought out an enlarged photograph.

“This is my method in such cases,” I explained. I stepped to my bureau and brought out an enlarged photograph.

“This is my method in such cases,” I explained.

“You certainly do things thoroughly, Mr. Holmes.” “You certainly do things thoroughly, Mr. Holmes.”

“I should hardly be what I am if I did not. Now let us

consider this weal which extends round the right shoulder. Do you observe nothing

remarkable?” “I should hardly be what I am if I did not. Now let us

consider this weal which extends round the right shoulder. Do you observe nothing

remarkable?”

“I can’t say I do.” “I can’t say I do.”

“Surely it is evident that it is unequal in its

intensity. There is a dot of extravasated blood here, and another there. There are similar

indications in this other weal down here. What can that mean?” “Surely it is evident that it is unequal in its

intensity. There is a dot of extravasated blood here, and another there. There are similar

indications in this other weal down here. What can that mean?”

“I have no idea. Have you?” “I have no idea. Have you?”

“Perhaps I have. Perhaps I haven’t. I may be able to

say more soon. Anything which will define what made that mark will bring us a long way

towards the criminal.” “Perhaps I have. Perhaps I haven’t. I may be able to

say more soon. Anything which will define what made that mark will bring us a long way

towards the criminal.”

“It is, of course, an absurd idea,” said the

policeman, “but if a red-hot net of wire had been laid across the back, then these

better marked points would represent where the meshes crossed each other.” “It is, of course, an absurd idea,” said the

policeman, “but if a red-hot net of wire had been laid across the back, then these

better marked points would represent where the meshes crossed each other.”

“A most ingenious comparison. Or shall we say a very

stiff cat-o’-nine-tails with small hard knots upon it?” “A most ingenious comparison. Or shall we say a very

stiff cat-o’-nine-tails with small hard knots upon it?”

“By Jove, Mr. Holmes, I think you have hit it.” “By Jove, Mr. Holmes, I think you have hit it.”

“Or there may be some very different cause, Mr. Bardle.

But your case is far too weak for an arrest. Besides, we have those last words–the

‘Lion’s Mane.’ ” “Or there may be some very different cause, Mr. Bardle.

But your case is far too weak for an arrest. Besides, we have those last words–the

‘Lion’s Mane.’ ”

“I have wondered whether Ian– –” “I have wondered whether Ian– –”

“Yes, I have considered that. If the second word had

borne any resemblance to Murdoch–but it did not. He gave it almost in a shriek. I am

sure that it was ‘Mane.’ ” “Yes, I have considered that. If the second word had

borne any resemblance to Murdoch–but it did not. He gave it almost in a shriek. I am

sure that it was ‘Mane.’ ”

“Have you no alternative, Mr. Holmes?” “Have you no alternative, Mr. Holmes?”

“Perhaps I have. But I do not care to discuss it until

there is something more solid to discuss.” “Perhaps I have. But I do not care to discuss it until

there is something more solid to discuss.”

“And when will that be?” “And when will that be?”

“In an hour–possibly less.” “In an hour–possibly less.”

The inspector rubbed his chin and looked at me with dubious

eyes. The inspector rubbed his chin and looked at me with dubious

eyes.

[1092] “I

wish I could see what was in your mind, Mr. Holmes. Perhaps it’s those

fishing-boats.” [1092] “I

wish I could see what was in your mind, Mr. Holmes. Perhaps it’s those

fishing-boats.”

“No, no, they were too far out.” “No, no, they were too far out.”

“Well, then, is it Bellamy and that big son of his? They

were not too sweet upon Mr. McPherson. Could they have done him a mischief?” “Well, then, is it Bellamy and that big son of his? They

were not too sweet upon Mr. McPherson. Could they have done him a mischief?”

“No, no, you won’t draw me until I am ready,”

said I with a smile. “Now, Inspector, we each have our own work to do. Perhaps if you

were to meet me here at midday– –” “No, no, you won’t draw me until I am ready,”

said I with a smile. “Now, Inspector, we each have our own work to do. Perhaps if you

were to meet me here at midday– –”

So far we had got when there came the tremendous interruption

which was the beginning of the end. So far we had got when there came the tremendous interruption

which was the beginning of the end.

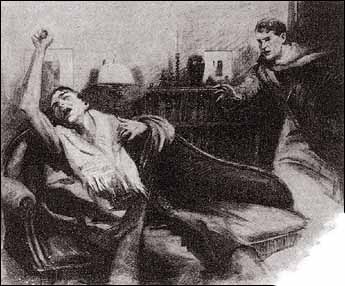

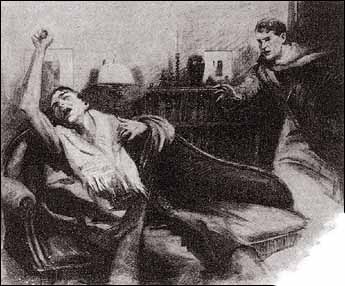

My outer door was flung open, there were blundering footsteps

in the passage, and Ian Murdoch staggered into the room, pallid, dishevelled, his clothes

in wild disorder, clawing with his bony hands at the furniture to hold himself erect.

“Brandy! Brandy!” he gasped, and fell groaning upon the sofa. My outer door was flung open, there were blundering footsteps

in the passage, and Ian Murdoch staggered into the room, pallid, dishevelled, his clothes

in wild disorder, clawing with his bony hands at the furniture to hold himself erect.

“Brandy! Brandy!” he gasped, and fell groaning upon the sofa.

He was not alone. Behind him came Stackhurst, hatless and

panting, almost as distrait as his companion. He was not alone. Behind him came Stackhurst, hatless and

panting, almost as distrait as his companion.

“Yes, yes, brandy!” he cried. “The man is at

his last gasp. It was all I could do to bring him here. He fainted twice upon the

way.” “Yes, yes, brandy!” he cried. “The man is at

his last gasp. It was all I could do to bring him here. He fainted twice upon the

way.”

Half a tumbler of the raw spirit brought about a wondrous

change. He pushed himself up on one arm and swung his coat from his shoulders. “For

God’s sake, oil, opium, morphia!” he cried. “Anything to ease this infernal

agony!” Half a tumbler of the raw spirit brought about a wondrous

change. He pushed himself up on one arm and swung his coat from his shoulders. “For

God’s sake, oil, opium, morphia!” he cried. “Anything to ease this infernal

agony!”

The inspector and I cried out at the sight. There,

crisscrossed upon the man’s naked shoulder, was the same strange reticulated pattern

of red, inflamed lines which had been the death-mark of Fitzroy McPherson. The inspector and I cried out at the sight. There,

crisscrossed upon the man’s naked shoulder, was the same strange reticulated pattern

of red, inflamed lines which had been the death-mark of Fitzroy McPherson.

The pain was evidently terrible and was more than local, for

the sufferer’s breathing would stop for a time, his face would turn black, and then

with loud gasps he would clap his hand to his heart, while his brow dropped beads of

sweat. At any moment he might die. More and more brandy was poured down his throat, each

fresh dose bringing him back to life. Pads of cotton-wool soaked in salad-oil seemed to

take the agony from the strange wounds. At last his head fell heavily upon the cushion.

Exhausted Nature had taken refuge in its last storehouse of vitality. It was half a sleep

and half a faint, but at least it was ease from pain. The pain was evidently terrible and was more than local, for

the sufferer’s breathing would stop for a time, his face would turn black, and then

with loud gasps he would clap his hand to his heart, while his brow dropped beads of

sweat. At any moment he might die. More and more brandy was poured down his throat, each

fresh dose bringing him back to life. Pads of cotton-wool soaked in salad-oil seemed to

take the agony from the strange wounds. At last his head fell heavily upon the cushion.

Exhausted Nature had taken refuge in its last storehouse of vitality. It was half a sleep

and half a faint, but at least it was ease from pain.

To question him had been impossible, but the moment we were

assured of his condition Stackhurst turned upon me. To question him had been impossible, but the moment we were

assured of his condition Stackhurst turned upon me.

“My God!” he cried, “what is it, Holmes? What

is it?” “My God!” he cried, “what is it, Holmes? What

is it?”

“Where did you find him?” “Where did you find him?”

“Down on the beach. Exactly where poor McPherson met his

end. If this man’s heart had been weak as McPherson’s was, he would not be here

now. More than once I thought he was gone as I brought him up. It was too far to The

Gables, so I made for you.” “Down on the beach. Exactly where poor McPherson met his

end. If this man’s heart had been weak as McPherson’s was, he would not be here

now. More than once I thought he was gone as I brought him up. It was too far to The

Gables, so I made for you.”

“Did you see him on the beach?” “Did you see him on the beach?”

“I was walking on the cliff when I heard his cry. He was

at the edge of the water, reeling about like a drunken man. I ran down, threw some clothes

about him, and brought him up. For heaven’s sake, Holmes, use all the powers you have

and spare no pains to lift the curse from this place, for life is becoming unendurable.

Can you, with all your world-wide reputation, do nothing for us?” “I was walking on the cliff when I heard his cry. He was

at the edge of the water, reeling about like a drunken man. I ran down, threw some clothes

about him, and brought him up. For heaven’s sake, Holmes, use all the powers you have

and spare no pains to lift the curse from this place, for life is becoming unendurable.

Can you, with all your world-wide reputation, do nothing for us?”

“I think I can, Stackhurst. Come with me now! And you,

Inspector, come along! We will see if we cannot deliver this murderer into your

hands.” “I think I can, Stackhurst. Come with me now! And you,

Inspector, come along! We will see if we cannot deliver this murderer into your

hands.”

Leaving the unconscious man in the charge of my housekeeper,

we all three [1093] went

down to the deadly lagoon. On the shingle there was piled a little heap of towels and

clothes left by the stricken man. Slowly I walked round the edge of the water, my comrades

in Indian file behind me. Most of the pool was quite shallow, but under the cliff where

the beach was hollowed out it was four or five feet deep. It was to this part that a

swimmer would naturally go, for it formed a beautiful pellucid green pool as clear as

crystal. A line of rocks lay above it at the base of the cliff, and along this I led the

way, peering eagerly into the depths beneath me. I had reached the deepest and stillest

pool when my eyes caught that for which they were searching, and I burst into a shout of

triumph. Leaving the unconscious man in the charge of my housekeeper,

we all three [1093] went

down to the deadly lagoon. On the shingle there was piled a little heap of towels and

clothes left by the stricken man. Slowly I walked round the edge of the water, my comrades

in Indian file behind me. Most of the pool was quite shallow, but under the cliff where

the beach was hollowed out it was four or five feet deep. It was to this part that a

swimmer would naturally go, for it formed a beautiful pellucid green pool as clear as

crystal. A line of rocks lay above it at the base of the cliff, and along this I led the

way, peering eagerly into the depths beneath me. I had reached the deepest and stillest

pool when my eyes caught that for which they were searching, and I burst into a shout of

triumph.

“Cyanea!” I cried. “Cyanea! Behold the

Lion’s Mane!” “Cyanea!” I cried. “Cyanea! Behold the

Lion’s Mane!”

The strange object at which I pointed did indeed look like a

tangled mass torn from the mane of a lion. It lay upon a rocky shelf some three feet under

the water, a curious waving, vibrating, hairy creature with streaks of silver among its

yellow tresses. It pulsated with a slow, heavy dilation and contraction. The strange object at which I pointed did indeed look like a

tangled mass torn from the mane of a lion. It lay upon a rocky shelf some three feet under

the water, a curious waving, vibrating, hairy creature with streaks of silver among its

yellow tresses. It pulsated with a slow, heavy dilation and contraction.

“It has done mischief enough. Its day is over!” I

cried. “Help me, Stackhurst! Let us end the murderer forever.” “It has done mischief enough. Its day is over!” I

cried. “Help me, Stackhurst! Let us end the murderer forever.”

There was a big boulder just above the ledge, and we pushed it

until it fell with a tremendous splash into the water. When the ripples had cleared we saw

that it had settled upon the ledge below. One flapping edge of yellow membrane showed that

our victim was beneath it. A thick oily scum oozed out from below the stone and stained

the water round, rising slowly to the surface. There was a big boulder just above the ledge, and we pushed it

until it fell with a tremendous splash into the water. When the ripples had cleared we saw

that it had settled upon the ledge below. One flapping edge of yellow membrane showed that

our victim was beneath it. A thick oily scum oozed out from below the stone and stained

the water round, rising slowly to the surface.

“Well, this gets me!” cried the inspector.

“What was it, Mr. Holmes? I’m born and bred in these parts, but I never saw such

a thing. It don’t belong to Sussex.” “Well, this gets me!” cried the inspector.

“What was it, Mr. Holmes? I’m born and bred in these parts, but I never saw such

a thing. It don’t belong to Sussex.”

“Just as well for Sussex,” I remarked. “It may

have been the southwest gale that brought it up. Come back to my house, both of you, and I

will give you the terrible experience of one who has good reason to remember his own

meeting with the same peril of the seas.” “Just as well for Sussex,” I remarked. “It may

have been the southwest gale that brought it up. Come back to my house, both of you, and I

will give you the terrible experience of one who has good reason to remember his own

meeting with the same peril of the seas.”

When we reached my study we found that Murdoch was so far

recovered that he could sit up. He was dazed in mind, and every now and then was shaken by

a paroxysm of pain. In broken words he explained that he had no notion what had occurred

to him, save that terrific pangs had suddenly shot through him, and that it had taken all

his fortitude to reach the bank. When we reached my study we found that Murdoch was so far

recovered that he could sit up. He was dazed in mind, and every now and then was shaken by

a paroxysm of pain. In broken words he explained that he had no notion what had occurred

to him, save that terrific pangs had suddenly shot through him, and that it had taken all

his fortitude to reach the bank.

“Here is a book,” I said, taking up the little

volume, “which first brought light into what might have been forever dark. It is Out

of Doors, by the famous observer, J. G. Wood. Wood himself very nearly perished from

contact with this vile creature, so he wrote with a very full knowledge. Cyanea

capillata is the miscreant’s full name, and he can be as dangerous to life as,

and far more painful than, the bite of the cobra. Let me briefly give this extract. “Here is a book,” I said, taking up the little

volume, “which first brought light into what might have been forever dark. It is Out

of Doors, by the famous observer, J. G. Wood. Wood himself very nearly perished from

contact with this vile creature, so he wrote with a very full knowledge. Cyanea

capillata is the miscreant’s full name, and he can be as dangerous to life as,

and far more painful than, the bite of the cobra. Let me briefly give this extract.

“If the bather should see a loose roundish mass of

tawny membranes and fibres, something like very large handfuls of lion’s mane and

silver paper, let him beware, for this is the fearful stinger, Cyanea capillata. “If the bather should see a loose roundish mass of

tawny membranes and fibres, something like very large handfuls of lion’s mane and

silver paper, let him beware, for this is the fearful stinger, Cyanea capillata.

Could our sinister acquaintance be more clearly described?

“He goes on to tell of his own encounter with one when

swimming off the coast of Kent. He found that the creature radiated almost invisible

filaments to the distance of fifty feet, and that anyone within that circumference from

the deadly centre was in danger of death. Even at a distance the effect upon Wood was

almost fatal. “He goes on to tell of his own encounter with one when

swimming off the coast of Kent. He found that the creature radiated almost invisible

filaments to the distance of fifty feet, and that anyone within that circumference from

the deadly centre was in danger of death. Even at a distance the effect upon Wood was

almost fatal.

[1094]

“The multitudinous threads caused light scarlet lines upon the skin which on

closer examination resolved into minute dots or pustules, each dot charged as it were with

a red-hot needle making its way through the nerves. [1094]

“The multitudinous threads caused light scarlet lines upon the skin which on

closer examination resolved into minute dots or pustules, each dot charged as it were with

a red-hot needle making its way through the nerves.

“The local pain was, as he explains, the least part of

the exquisite torment. “The local pain was, as he explains, the least part of

the exquisite torment.

“Pangs shot through the chest, causing me to fall as if

struck by a bullet. The pulsation would cease, and then the heart would give six or seven

leaps as if it would force its way through the chest. “Pangs shot through the chest, causing me to fall as if

struck by a bullet. The pulsation would cease, and then the heart would give six or seven

leaps as if it would force its way through the chest.

“It nearly killed him, although he had only been

exposed to it in the disturbed ocean and not in the narrow calm waters of a bathing-pool.

He says that he could hardly recognize himself afterwards, so white, wrinkled and

shrivelled was his face. He gulped down brandy, a whole bottleful, and it seems to have

saved his life. There is the book, Inspector. I leave it with you, and you cannot doubt

that it contains a full explanation of the tragedy of poor McPherson.” “It nearly killed him, although he had only been

exposed to it in the disturbed ocean and not in the narrow calm waters of a bathing-pool.

He says that he could hardly recognize himself afterwards, so white, wrinkled and

shrivelled was his face. He gulped down brandy, a whole bottleful, and it seems to have

saved his life. There is the book, Inspector. I leave it with you, and you cannot doubt

that it contains a full explanation of the tragedy of poor McPherson.”

“And incidentally exonerates me,” remarked Ian

Murdoch with a wry smile. “I do not blame you, Inspector, nor you, Mr. Holmes, for

your suspicions were natural. I feel that on the very eve of my arrest I have only cleared

myself by sharing the fate of my poor friend.” “And incidentally exonerates me,” remarked Ian

Murdoch with a wry smile. “I do not blame you, Inspector, nor you, Mr. Holmes, for

your suspicions were natural. I feel that on the very eve of my arrest I have only cleared

myself by sharing the fate of my poor friend.”

“No, Mr. Murdoch. I was already upon the track, and had I

been out as early as I intended I might well have saved you from this terrific

experience.” “No, Mr. Murdoch. I was already upon the track, and had I

been out as early as I intended I might well have saved you from this terrific

experience.”

“But how did you know, Mr. Holmes?” “But how did you know, Mr. Holmes?”

“I am an omnivorous reader with a strangely retentive

memory for trifles. That phrase ‘the Lion’s Mane’ haunted my mind. I knew

that I had seen it somewhere in an unexpected context. You have seen that it does describe

the creature. I have no doubt that it was floating on the water when McPherson saw it, and

that this phrase was the only one by which he could convey to us a warning as to the

creature which had been his death.” “I am an omnivorous reader with a strangely retentive

memory for trifles. That phrase ‘the Lion’s Mane’ haunted my mind. I knew

that I had seen it somewhere in an unexpected context. You have seen that it does describe

the creature. I have no doubt that it was floating on the water when McPherson saw it, and

that this phrase was the only one by which he could convey to us a warning as to the

creature which had been his death.”

“Then I, at least, am cleared,” said Murdoch, rising

slowly to his feet. “There are one or two words of explanation which I should give,

for I know the direction in which your inquiries have run. It is true that I loved this

lady, but from the day when she chose my friend McPherson my one desire was to help her to

happiness. I was well content to stand aside and act as their go-between. Often I carried

their messages, and it was because I was in their confidence and because she was so dear

to me that I hastened to tell her of my friend’s death, lest someone should forestall

me in a more sudden and heartless manner. She would not tell you, sir, of our relations

lest you should disapprove and I might suffer. But with your leave I must try to get back

to The Gables, for my bed will be very welcome.” “Then I, at least, am cleared,” said Murdoch, rising

slowly to his feet. “There are one or two words of explanation which I should give,

for I know the direction in which your inquiries have run. It is true that I loved this

lady, but from the day when she chose my friend McPherson my one desire was to help her to

happiness. I was well content to stand aside and act as their go-between. Often I carried

their messages, and it was because I was in their confidence and because she was so dear

to me that I hastened to tell her of my friend’s death, lest someone should forestall

me in a more sudden and heartless manner. She would not tell you, sir, of our relations

lest you should disapprove and I might suffer. But with your leave I must try to get back

to The Gables, for my bed will be very welcome.”

Stackhurst held out his hand. “Our nerves have all been

at concert-pitch,” said he. “Forgive what is past, Murdoch. We shall understand

each other better in the future.” They passed out together with their arms linked in

friendly fashion. The inspector remained, staring at me in silence with his ox-like eyes. Stackhurst held out his hand. “Our nerves have all been

at concert-pitch,” said he. “Forgive what is past, Murdoch. We shall understand

each other better in the future.” They passed out together with their arms linked in

friendly fashion. The inspector remained, staring at me in silence with his ox-like eyes.

“Well, you’ve done it!” he cried at last.

“I had read of you, but I never believed it. It’s wonderful!” “Well, you’ve done it!” he cried at last.

“I had read of you, but I never believed it. It’s wonderful!”

I was forced to shake my head. To accept such praise was to

lower one’s own standards. I was forced to shake my head. To accept such praise was to

lower one’s own standards.

“I was slow at the outset–culpably slow. Had the

body been found in the water I could hardly have missed it. It was the towel which misled

me. The poor fellow had never thought to dry himself, and so I in turn was led to believe

that he had [1095] never

been in the water. Why, then, should the attack of any water creature suggest itself to

me? That was where I went astray. Well, well, Inspector, I often ventured to chaff you

gentlemen of the police force, but Cyanea capillata very nearly avenged Scotland

Yard.” “I was slow at the outset–culpably slow. Had the

body been found in the water I could hardly have missed it. It was the towel which misled

me. The poor fellow had never thought to dry himself, and so I in turn was led to believe

that he had [1095] never

been in the water. Why, then, should the attack of any water creature suggest itself to

me? That was where I went astray. Well, well, Inspector, I often ventured to chaff you

gentlemen of the police force, but Cyanea capillata very nearly avenged Scotland

Yard.”

|

![]() My villa is situated upon the southern slope of the downs,

commanding a great view of the Channel. At this point the coast-line is entirely of chalk

cliffs, which can only be descended by a single, long, tortuous path, which is steep and

slippery. At the bottom of the path lie a hundred yards of pebbles and shingle, even when

the tide is at full. Here and there, however, there are curves and hollows which make

splendid swimming-pools filled afresh with each flow. This admirable beach extends for

some miles in each direction, save only at one point where the little cove and village of

Fulworth break the line.

My villa is situated upon the southern slope of the downs,

commanding a great view of the Channel. At this point the coast-line is entirely of chalk

cliffs, which can only be descended by a single, long, tortuous path, which is steep and

slippery. At the bottom of the path lie a hundred yards of pebbles and shingle, even when

the tide is at full. Here and there, however, there are curves and hollows which make

splendid swimming-pools filled afresh with each flow. This admirable beach extends for

some miles in each direction, save only at one point where the little cove and village of

Fulworth break the line.![]() My house is lonely. I, my old housekeeper, and my bees have

the estate all to ourselves. Half a mile off, however, is Harold Stackhurst’s

well-known coaching establishment, The Gables, quite a large place, which contains some

score of young fellows preparing for various professions, with a staff of several masters.

Stackhurst himself was a well-known rowing Blue in his day, and an excellent all-round

scholar. He and I were always friendly from the day I came to the coast, and he was the

one man who was on such terms with me that we could drop in on each other in the evenings

without an invitation.

My house is lonely. I, my old housekeeper, and my bees have

the estate all to ourselves. Half a mile off, however, is Harold Stackhurst’s

well-known coaching establishment, The Gables, quite a large place, which contains some

score of young fellows preparing for various professions, with a staff of several masters.

Stackhurst himself was a well-known rowing Blue in his day, and an excellent all-round

scholar. He and I were always friendly from the day I came to the coast, and he was the

one man who was on such terms with me that we could drop in on each other in the evenings

without an invitation.![]() Towards the end of July, 1907, there was a severe gale, the

wind blowing up-channel, heaping the seas to the base of the cliffs and leaving a lagoon

at the turn of the tide. On the morning of which I speak the wind had abated, and all

Nature was newly washed and fresh. It was impossible to work upon so delightful a day, [1084] and I strolled out before

breakfast to enjoy the exquisite air. I walked along the cliff path which led to the steep

descent to the beach. As I walked I heard a shout behind me, and there was Harold

Stackhurst waving his hand in cheery greeting.

Towards the end of July, 1907, there was a severe gale, the

wind blowing up-channel, heaping the seas to the base of the cliffs and leaving a lagoon

at the turn of the tide. On the morning of which I speak the wind had abated, and all

Nature was newly washed and fresh. It was impossible to work upon so delightful a day, [1084] and I strolled out before

breakfast to enjoy the exquisite air. I walked along the cliff path which led to the steep

descent to the beach. As I walked I heard a shout behind me, and there was Harold

Stackhurst waving his hand in cheery greeting.![]() “What a morning, Mr. Holmes! I thought I should see you

out.”

“What a morning, Mr. Holmes! I thought I should see you

out.”![]() “Going for a swim, I see.”

“Going for a swim, I see.”![]() “At your old tricks again,” he laughed, patting his

bulging pocket. “Yes. McPherson started early, and I expect I may find him

there.”

“At your old tricks again,” he laughed, patting his

bulging pocket. “Yes. McPherson started early, and I expect I may find him

there.”![]() Fitzroy McPherson was the science master, a fine upstanding

young fellow whose life had been crippled by heart trouble following rheumatic fever. He

was a natural athlete, however, and excelled in every game which did not throw too great a

strain upon him. Summer and winter he went for his swim, and, as I am a swimmer myself, I

have often joined him.

Fitzroy McPherson was the science master, a fine upstanding

young fellow whose life had been crippled by heart trouble following rheumatic fever. He

was a natural athlete, however, and excelled in every game which did not throw too great a

strain upon him. Summer and winter he went for his swim, and, as I am a swimmer myself, I

have often joined him.![]() At this moment we saw the man himself. His head showed above

the edge of the cliff where the path ends. Then his whole figure appeared at the top,

staggering like a drunken man. The next instant he threw up his hands and, with a terrible

cry, fell upon his face. Stackhurst and I rushed forward–it may have been fifty

yards–and turned him on his back. He was obviously dying. Those glazed sunken eyes