|

|

The address was “The Three Gables, Harrow Weald.” The address was “The Three Gables, Harrow Weald.”

“So that’s that!” said Holmes. “And now,

if you can spare the time, Watson, we will get upon our way.” “So that’s that!” said Holmes. “And now,

if you can spare the time, Watson, we will get upon our way.”

A short railway journey, and a shorter drive, brought us to

the house, a brick and timber villa, standing in its own acre of undeveloped grassland.

Three small projections above the upper windows made a feeble attempt to justify its name.

Behind was a grove of melancholy, half-grown pines, and the whole aspect of the place was

poor and depressing. None the less, we found the house to be well furnished, and the lady

who received us was a most engaging elderly person, who bore every mark of refinement and

culture. A short railway journey, and a shorter drive, brought us to

the house, a brick and timber villa, standing in its own acre of undeveloped grassland.

Three small projections above the upper windows made a feeble attempt to justify its name.

Behind was a grove of melancholy, half-grown pines, and the whole aspect of the place was

poor and depressing. None the less, we found the house to be well furnished, and the lady

who received us was a most engaging elderly person, who bore every mark of refinement and

culture.

“I remember your husband well, madam,” said Holmes,

“though it is some years since he used my services in some trifling matter.” “I remember your husband well, madam,” said Holmes,

“though it is some years since he used my services in some trifling matter.”

[1025]

“Probably you would be more familiar with the name of my son Douglas.” [1025]

“Probably you would be more familiar with the name of my son Douglas.”

Holmes looked at her with great interest. Holmes looked at her with great interest.

“Dear me! Are you the mother of Douglas Maberley? I knew

him slightly. But of course all London knew him. What a magnificent creature he was! Where

is he now?” “Dear me! Are you the mother of Douglas Maberley? I knew

him slightly. But of course all London knew him. What a magnificent creature he was! Where

is he now?”

“Dead, Mr. Holmes, dead! He was attache at Rome, and he

died there of pneumonia last month.” “Dead, Mr. Holmes, dead! He was attache at Rome, and he

died there of pneumonia last month.”

“I am sorry. One could not connect death with such a man.

I have never known anyone so vitally alive. He lived intensely–every fibre of

him!” “I am sorry. One could not connect death with such a man.

I have never known anyone so vitally alive. He lived intensely–every fibre of

him!”

“Too intensely, Mr. Holmes. That was the ruin of him. You

remember him as he was–debonair and splendid. You did not see the moody, morose,

brooding creature into which he developed. His heart was broken. In a single month I

seemed to see my gallant boy turn into a worn-out cynical man.” “Too intensely, Mr. Holmes. That was the ruin of him. You

remember him as he was–debonair and splendid. You did not see the moody, morose,

brooding creature into which he developed. His heart was broken. In a single month I

seemed to see my gallant boy turn into a worn-out cynical man.”

“A love affair–a woman?” “A love affair–a woman?”

“Or a fiend. Well, it was not to talk of my poor lad that

I asked you to come, Mr. Holmes.” “Or a fiend. Well, it was not to talk of my poor lad that

I asked you to come, Mr. Holmes.”

“Dr. Watson and I are at your service.” “Dr. Watson and I are at your service.”

“There have been some very strange happenings. I have

been in this house more than a year now, and as I wished to lead a retired life I have

seen little of my neighbours. Three days ago I had a call from a man who said that he was

a house agent. He said that this house would exactly suit a client of his, and that if I

would part with it money would be no object. It seemed to me very strange as there are

several empty houses on the market which appear to be equally eligible, but naturally I

was interested in what he said. I therefore named a price which was five hundred pounds

more than I gave. He at once closed with the offer, but added that his client desired to

buy the furniture as well and would I put a price upon it. Some of this furniture is from

my old home, and it is, as you see, very good, so that I named a good round sum. To this

also he at once agreed. I had always wanted to travel, and the bargain was so good a one

that it really seemed that I should be my own mistress for the rest of my life. “There have been some very strange happenings. I have

been in this house more than a year now, and as I wished to lead a retired life I have

seen little of my neighbours. Three days ago I had a call from a man who said that he was

a house agent. He said that this house would exactly suit a client of his, and that if I

would part with it money would be no object. It seemed to me very strange as there are

several empty houses on the market which appear to be equally eligible, but naturally I

was interested in what he said. I therefore named a price which was five hundred pounds

more than I gave. He at once closed with the offer, but added that his client desired to

buy the furniture as well and would I put a price upon it. Some of this furniture is from

my old home, and it is, as you see, very good, so that I named a good round sum. To this

also he at once agreed. I had always wanted to travel, and the bargain was so good a one

that it really seemed that I should be my own mistress for the rest of my life.

“Yesterday the man arrived with the agreement all drawn

out. Luckily I showed it to Mr. Sutro, my lawyer, who lives in Harrow. He said to me,

‘This is a very strange document. Are you aware that if you sign it you could not

legally take anything out of the house–not even your own private

possessions?’ When the man came again in the evening I pointed this out, and I said

that I meant only to sell the furniture. “Yesterday the man arrived with the agreement all drawn

out. Luckily I showed it to Mr. Sutro, my lawyer, who lives in Harrow. He said to me,

‘This is a very strange document. Are you aware that if you sign it you could not

legally take anything out of the house–not even your own private

possessions?’ When the man came again in the evening I pointed this out, and I said

that I meant only to sell the furniture.

“ ‘No, no, everything,’ said he. “ ‘No, no, everything,’ said he.

“ ‘But my clothes? My jewels?’ “ ‘But my clothes? My jewels?’

“ ‘Well, well, some concession might be made for

your personal effects. But nothing shall go out of the house unchecked. My client is a

very liberal man, but he has his fads and his own way of doing things. It is everything or

nothing with him.’ “ ‘Well, well, some concession might be made for

your personal effects. But nothing shall go out of the house unchecked. My client is a

very liberal man, but he has his fads and his own way of doing things. It is everything or

nothing with him.’

“ ‘Then it must be nothing,’ said I. And there

the matter was left, but the whole thing seemed to me to be so unusual that I

thought– –” “ ‘Then it must be nothing,’ said I. And there

the matter was left, but the whole thing seemed to me to be so unusual that I

thought– –”

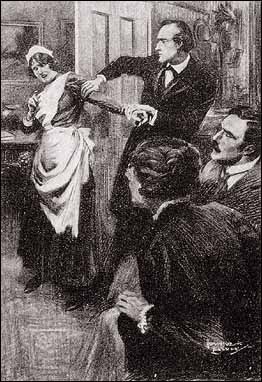

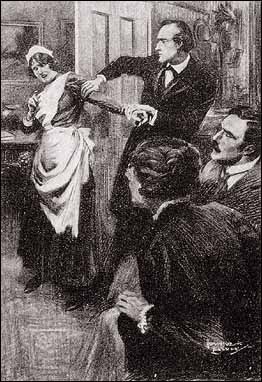

Here we had a very extraordinary interruption. Here we had a very extraordinary interruption.

Holmes raised his hand for silence. Then he strode across the

room, flung open the door, and dragged in a great gaunt woman whom he had seized by the

shoulder. She entered with ungainly struggle like some huge awkward chicken, torn,

squawking, out of its coop. Holmes raised his hand for silence. Then he strode across the

room, flung open the door, and dragged in a great gaunt woman whom he had seized by the

shoulder. She entered with ungainly struggle like some huge awkward chicken, torn,

squawking, out of its coop.

[1026]

“Leave me alone! What are you a-doin’ of?” she screeched. [1026]

“Leave me alone! What are you a-doin’ of?” she screeched.

“Why, Susan, what is this?” “Why, Susan, what is this?”

“Well, ma’am, I was comin’ in to ask if the

visitors was stayin’ for lunch when this man jumped out at me.” “Well, ma’am, I was comin’ in to ask if the

visitors was stayin’ for lunch when this man jumped out at me.”

“I have been listening to her for the last five minutes,

but did not wish to interrupt your most interesting narrative. Just a little wheezy,

Susan, are you not? You breathe too heavily for that kind of work.” “I have been listening to her for the last five minutes,

but did not wish to interrupt your most interesting narrative. Just a little wheezy,

Susan, are you not? You breathe too heavily for that kind of work.”

Susan turned a sulky but amazed face upon her captor.

“Who be you, anyhow, and what right have you a-pullin’ me about like this?” Susan turned a sulky but amazed face upon her captor.

“Who be you, anyhow, and what right have you a-pullin’ me about like this?”

“It was merely that I wished to ask a question in your

presence. Did you, Mrs. Maberley, mention to anyone that you were going to write to me and

consult me?” “It was merely that I wished to ask a question in your

presence. Did you, Mrs. Maberley, mention to anyone that you were going to write to me and

consult me?”

“No, Mr. Holmes, I did not.” “No, Mr. Holmes, I did not.”

“Who posted your letter?” “Who posted your letter?”

“Susan did.” “Susan did.”

“Exactly. Now, Susan, to whom was it that you wrote or

sent a message to say that your mistress was asking advice from me?” “Exactly. Now, Susan, to whom was it that you wrote or

sent a message to say that your mistress was asking advice from me?”

“It’s a lie. I sent no message.” “It’s a lie. I sent no message.”

“Now, Susan, wheezy people may not live long, you know.

It’s a wicked thing to tell fibs. Whom did you tell?” “Now, Susan, wheezy people may not live long, you know.

It’s a wicked thing to tell fibs. Whom did you tell?”

“Susan!” cried her mistress, “I believe you are

a bad, treacherous woman. I remember now that I saw you speaking to someone over the

hedge.” “Susan!” cried her mistress, “I believe you are

a bad, treacherous woman. I remember now that I saw you speaking to someone over the

hedge.”

“That was my own business,” said the woman sullenly. “That was my own business,” said the woman sullenly.

“Suppose I tell you that it was Barney Stockdale to whom

you spoke?” said Holmes. “Suppose I tell you that it was Barney Stockdale to whom

you spoke?” said Holmes.

“Well, if you know, what do you want to ask for?” “Well, if you know, what do you want to ask for?”

“I was not sure, but I know now. Well now, Susan, it will

be worth ten pounds to you if you will tell me who is at the back of Barney.” “I was not sure, but I know now. Well now, Susan, it will

be worth ten pounds to you if you will tell me who is at the back of Barney.”

“Someone that could lay down a thousand pounds for every

ten you have in the world.” “Someone that could lay down a thousand pounds for every

ten you have in the world.”

“So, a rich man? No; you smiled–a rich woman. Now we

have got so far, you may as well give the name and earn the tenner.” “So, a rich man? No; you smiled–a rich woman. Now we

have got so far, you may as well give the name and earn the tenner.”

“I’ll see you in hell first.” “I’ll see you in hell first.”

“Oh, Susan! Language!” “Oh, Susan! Language!”

“I am clearing out of here. I’ve had enough of you

all. I’ll send for my box to-morrow.” She flounced for the door. “I am clearing out of here. I’ve had enough of you

all. I’ll send for my box to-morrow.” She flounced for the door.

“Good-bye, Susan. Paregoric is the stuff. . . .

Now,” he continued, turning suddenly from lively to severe when the door had closed

behind the flushed and angry woman, “this gang means business. Look how close they

play the game. Your letter to me had the 10 P. M. postmark. And yet Susan

passes the word to Barney. Barney has time to go to his employer and get instructions; he

or she–I incline to the latter from Susan’s grin when she thought I had

blundered–forms a plan. Black Steve is called in, and I am warned off by eleven

o’clock next morning. That’s quick work, you know.” “Good-bye, Susan. Paregoric is the stuff. . . .

Now,” he continued, turning suddenly from lively to severe when the door had closed

behind the flushed and angry woman, “this gang means business. Look how close they

play the game. Your letter to me had the 10 P. M. postmark. And yet Susan

passes the word to Barney. Barney has time to go to his employer and get instructions; he

or she–I incline to the latter from Susan’s grin when she thought I had

blundered–forms a plan. Black Steve is called in, and I am warned off by eleven

o’clock next morning. That’s quick work, you know.”

“But what do they want?” “But what do they want?”

“Yes, that’s the question. Who had the house before

you?” “Yes, that’s the question. Who had the house before

you?”

“A retired sea captain called Ferguson.” “A retired sea captain called Ferguson.”

“Anything remarkable about him?” “Anything remarkable about him?”

“Not that ever I heard of.” “Not that ever I heard of.”

“I was wondering whether he could have buried something.

Of course, when [1027]

people bury treasure nowadays they do it in the Post-Office bank. But there are always

some lunatics about. It would be a dull world without them. At first I thought of some

buried valuable. But why, in that case, should they want your furniture? You don’t

happen to have a Raphael or a first folio Shakespeare without knowing it?” “I was wondering whether he could have buried something.

Of course, when [1027]

people bury treasure nowadays they do it in the Post-Office bank. But there are always

some lunatics about. It would be a dull world without them. At first I thought of some

buried valuable. But why, in that case, should they want your furniture? You don’t

happen to have a Raphael or a first folio Shakespeare without knowing it?”

“No, I don’t think I have anything rarer than a

Crown Derby tea-set.” “No, I don’t think I have anything rarer than a

Crown Derby tea-set.”

“That would hardly justify all this mystery. Besides, why

should they not openly state what they want? If they covet your tea-set, they can surely

offer a price for it without buying you out, lock, stock, and barrel. No, as I read it,

there is something which you do not know that you have, and which you would not give up if

you did know.” “That would hardly justify all this mystery. Besides, why

should they not openly state what they want? If they covet your tea-set, they can surely

offer a price for it without buying you out, lock, stock, and barrel. No, as I read it,

there is something which you do not know that you have, and which you would not give up if

you did know.”

“That is how I read it,” said I. “That is how I read it,” said I.

“Dr. Watson agrees, so that settles it.” “Dr. Watson agrees, so that settles it.”

“Well, Mr. Holmes, what can it be?” “Well, Mr. Holmes, what can it be?”

“Let us see whether by this purely mental analysis we can

get it to a finer point. You have been in this house a year.” “Let us see whether by this purely mental analysis we can

get it to a finer point. You have been in this house a year.”

“Nearly two.” “Nearly two.”

“All the better. During this long period no one wants

anything from you. Now suddenly within three or four days you have urgent demands. What

would you gather from that?” “All the better. During this long period no one wants

anything from you. Now suddenly within three or four days you have urgent demands. What

would you gather from that?”

“It can only mean,” said I, “that the object,

whatever it may be, has only just come into the house.” “It can only mean,” said I, “that the object,

whatever it may be, has only just come into the house.”

“Settled once again,” said Holmes. “Now, Mrs.

Maberley, has any object just arrived?” “Settled once again,” said Holmes. “Now, Mrs.

Maberley, has any object just arrived?”

“No, I have bought nothing new this year.” “No, I have bought nothing new this year.”

“Indeed! That is very remarkable. Well, I think we had

best let matters develop a little further until we have clearer data. Is that lawyer of

yours a capable man?” “Indeed! That is very remarkable. Well, I think we had

best let matters develop a little further until we have clearer data. Is that lawyer of

yours a capable man?”

“Mr. Sutro is most capable.” “Mr. Sutro is most capable.”

“Have you another maid, or was the fair Susan, who has

just banged your front door, alone?” “Have you another maid, or was the fair Susan, who has

just banged your front door, alone?”

“I have a young girl.” “I have a young girl.”

“Try and get Sutro to spend a night or two in the house.

You might possibly want protection.” “Try and get Sutro to spend a night or two in the house.

You might possibly want protection.”

“Against whom?” “Against whom?”

“Who knows? The matter is certainly obscure. If I

can’t find what they are after, I must approach the matter from the other end and try

to get at the principal. Did this house-agent man give any address?” “Who knows? The matter is certainly obscure. If I

can’t find what they are after, I must approach the matter from the other end and try

to get at the principal. Did this house-agent man give any address?”

“Simply his card and occupation. Haines-Johnson,

Auctioneer and Valuer.” “Simply his card and occupation. Haines-Johnson,

Auctioneer and Valuer.”

“I don’t think we shall find him in the directory.

Honest business men don’t conceal their place of business. Well, you will let me know

any fresh development. I have taken up your case, and you may rely upon it that I shall

see it through.” “I don’t think we shall find him in the directory.

Honest business men don’t conceal their place of business. Well, you will let me know

any fresh development. I have taken up your case, and you may rely upon it that I shall

see it through.”

As we passed through the hall Holmes’s eyes, which missed

nothing, lighted upon several trunks and cases which were piled in a corner. The labels

shone out upon them. As we passed through the hall Holmes’s eyes, which missed

nothing, lighted upon several trunks and cases which were piled in a corner. The labels

shone out upon them.

“ ‘Milano.’ ‘Lucerne.’ These are from

Italy.” “ ‘Milano.’ ‘Lucerne.’ These are from

Italy.”

“They are poor Douglas’s things.” “They are poor Douglas’s things.”

“You have not unpacked them? How long have you had

them?” “You have not unpacked them? How long have you had

them?”

“They arrived last week.” “They arrived last week.”

[1028]

“But you said–why, surely this might be the missing link. How do we know that

there is not something of value there?” [1028]

“But you said–why, surely this might be the missing link. How do we know that

there is not something of value there?”

“There could not possibly be, Mr. Holmes. Poor Douglas

had only his pay and a small annuity. What could he have of value?” “There could not possibly be, Mr. Holmes. Poor Douglas

had only his pay and a small annuity. What could he have of value?”

Holmes was lost in thought. Holmes was lost in thought.

“Delay no longer, Mrs. Maberley,” he said at last.

“Have these things taken upstairs to your bedroom. Examine them as soon as possible

and see what they contain. I will come to-morrow and hear your report.” “Delay no longer, Mrs. Maberley,” he said at last.

“Have these things taken upstairs to your bedroom. Examine them as soon as possible

and see what they contain. I will come to-morrow and hear your report.”

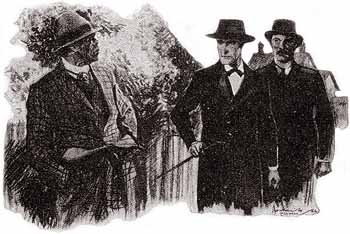

It was quite evident that The Three Gables was under very

close surveillance, for as we came round the high hedge at the end of the lane there was

the negro prize-fighter standing in the shadow. We came on him quite suddenly, and a grim

and menacing figure he looked in that lonely place. Holmes clapped his hand to his pocket. It was quite evident that The Three Gables was under very

close surveillance, for as we came round the high hedge at the end of the lane there was

the negro prize-fighter standing in the shadow. We came on him quite suddenly, and a grim

and menacing figure he looked in that lonely place. Holmes clapped his hand to his pocket.

“Lookin’ for your gun, Masser Holmes?” “Lookin’ for your gun, Masser Holmes?”

“No, for my scent-bottle, Steve.” “No, for my scent-bottle, Steve.”

“You are funny, Masser Holmes, ain’t you?” “You are funny, Masser Holmes, ain’t you?”

“It won’t be funny for you, Steve, if I get after

you. I gave you fair warning this morning.” “It won’t be funny for you, Steve, if I get after

you. I gave you fair warning this morning.”

“Well, Masser Holmes, I done gone think over what you

said, and I don’t want no more talk about that affair of Masser Perkins. S’pose

I can help you, Masser Holmes, I will.” “Well, Masser Holmes, I done gone think over what you

said, and I don’t want no more talk about that affair of Masser Perkins. S’pose

I can help you, Masser Holmes, I will.”

“Well, then, tell me who is behind you on this job.” “Well, then, tell me who is behind you on this job.”

“So help me the Lord! Masser Holmes, I told you the truth

before. I don’t know. My boss Barney gives me orders and that’s all.” “So help me the Lord! Masser Holmes, I told you the truth

before. I don’t know. My boss Barney gives me orders and that’s all.”

“Well, just bear in mind, Steve, that the lady in that

house, and everything under that roof, is under my protection. Don’t forget it.” “Well, just bear in mind, Steve, that the lady in that

house, and everything under that roof, is under my protection. Don’t forget it.”

“All right, Masser Holmes. I’ll remember.” “All right, Masser Holmes. I’ll remember.”

“I’ve got him thoroughly frightened for his own

skin, Watson,” Holmes remarked as we walked on. “I think he would double-cross

his employer if he knew who he was. It was lucky I had some knowledge of the Spencer John

crowd, and that Steve was one of them. Now, Watson, this is a case for Langdale Pike, and

I am going to see him now. When I get back I may be clearer in the matter.” “I’ve got him thoroughly frightened for his own

skin, Watson,” Holmes remarked as we walked on. “I think he would double-cross

his employer if he knew who he was. It was lucky I had some knowledge of the Spencer John

crowd, and that Steve was one of them. Now, Watson, this is a case for Langdale Pike, and

I am going to see him now. When I get back I may be clearer in the matter.”

I saw no more of Holmes during the day, but I could well

imagine how he spent it, for Langdale Pike was his human book of reference upon all

matters of social scandal. This strange, languid creature spent his waking hours in the

bow window of a St. James’s Street club and was the receiving-station as well as the

transmitter for all the gossip of the metropolis. He made, it was said, a four-figure

income by the paragraphs which he contributed every week to the garbage papers which cater

to an inquisitive public. If ever, far down in the turbid depths of London life, there was

some strange swirl or eddy, it was marked with automatic exactness by this human dial upon

the surface. Holmes discreetly helped Langdale to knowledge, and on occasion was helped in

turn. I saw no more of Holmes during the day, but I could well

imagine how he spent it, for Langdale Pike was his human book of reference upon all

matters of social scandal. This strange, languid creature spent his waking hours in the

bow window of a St. James’s Street club and was the receiving-station as well as the

transmitter for all the gossip of the metropolis. He made, it was said, a four-figure

income by the paragraphs which he contributed every week to the garbage papers which cater

to an inquisitive public. If ever, far down in the turbid depths of London life, there was

some strange swirl or eddy, it was marked with automatic exactness by this human dial upon

the surface. Holmes discreetly helped Langdale to knowledge, and on occasion was helped in

turn.

When I met my friend in his room early next morning, I was

conscious from his bearing that all was well, but none the less a most unpleasant surprise

was awaiting us. It took the shape of the following telegram: When I met my friend in his room early next morning, I was

conscious from his bearing that all was well, but none the less a most unpleasant surprise

was awaiting us. It took the shape of the following telegram:

Please come out at once. Client’s house burgled in the

night. Police in possession. Please come out at once. Client’s house burgled in the

night. Police in possession.

- SUTRO.

[1029]

Holmes whistled. “The drama has come to a crisis, and quicker than I had expected.

There is a great driving-power at the back of this business, Watson, which does not

surprise me after what I have heard. This Sutro, of course, is her lawyer. I made a

mistake, I fear, in not asking you to spend the night on guard. This fellow has clearly

proved a broken reed. Well, there is nothing for it but another journey to Harrow

Weald.” [1029]

Holmes whistled. “The drama has come to a crisis, and quicker than I had expected.

There is a great driving-power at the back of this business, Watson, which does not

surprise me after what I have heard. This Sutro, of course, is her lawyer. I made a

mistake, I fear, in not asking you to spend the night on guard. This fellow has clearly

proved a broken reed. Well, there is nothing for it but another journey to Harrow

Weald.”

We found The Three Gables a very different establishment to

the orderly household of the previous day. A small group of idlers had assembled at the

garden gate, while a couple of constables were examining the windows and the geranium

beds. Within we met a gray old gentleman, who introduced himself as the lawyer, together

with a bustling, rubicund inspector, who greeted Holmes as an old friend. We found The Three Gables a very different establishment to

the orderly household of the previous day. A small group of idlers had assembled at the

garden gate, while a couple of constables were examining the windows and the geranium

beds. Within we met a gray old gentleman, who introduced himself as the lawyer, together

with a bustling, rubicund inspector, who greeted Holmes as an old friend.

“Well, Mr. Holmes, no chance for you in this case,

I’m afraid. Just a common, ordinary burglary, and well within the capacity of the

poor old police. No experts need apply.” “Well, Mr. Holmes, no chance for you in this case,

I’m afraid. Just a common, ordinary burglary, and well within the capacity of the

poor old police. No experts need apply.”

“I am sure the case is in very good hands,” said

Holmes. “Merely a common burglary, you say?” “I am sure the case is in very good hands,” said

Holmes. “Merely a common burglary, you say?”

“Quite so. We know pretty well who the men are and where

to find them. It is that gang of Barney Stockdale, with the big nigger in

it–they’ve been seen about here.” “Quite so. We know pretty well who the men are and where

to find them. It is that gang of Barney Stockdale, with the big nigger in

it–they’ve been seen about here.”

“Excellent! What did they get?” “Excellent! What did they get?”

“Well, they don’t seem to have got much. Mrs.

Maberley was chloroformed and the house was– – Ah! here is the lady

herself.” “Well, they don’t seem to have got much. Mrs.

Maberley was chloroformed and the house was– – Ah! here is the lady

herself.”

Our friend of yesterday, looking very pale and ill, had

entered the room, leaning upon a little maidservant. Our friend of yesterday, looking very pale and ill, had

entered the room, leaning upon a little maidservant.

“You gave me good advice, Mr. Holmes,” said she,

smiling ruefully. “Alas, I did not take it! I did not wish to trouble Mr. Sutro, and

so I was unprotected.” “You gave me good advice, Mr. Holmes,” said she,

smiling ruefully. “Alas, I did not take it! I did not wish to trouble Mr. Sutro, and

so I was unprotected.”

“I only heard of it this morning,” the lawyer

explained. “I only heard of it this morning,” the lawyer

explained.

“Mr. Holmes advised me to have some friend in the house.

I neglected his advice, and I have paid for it.” “Mr. Holmes advised me to have some friend in the house.

I neglected his advice, and I have paid for it.”

“You look wretchedly ill,” said Holmes.

“Perhaps you are hardly equal to telling me what occurred.” “You look wretchedly ill,” said Holmes.

“Perhaps you are hardly equal to telling me what occurred.”

“It is all here,” said the inspector, tapping a

bulky notebook. “It is all here,” said the inspector, tapping a

bulky notebook.

“Still, if the lady is not too exhausted–

–” “Still, if the lady is not too exhausted–

–”

“There is really so little to tell. I have no doubt that

wicked Susan had planned an entrance for them. They must have known the house to an inch.

I was conscious for a moment of the chloroform rag which was thrust over my mouth, but I

have no notion how long I may have been senseless. When I woke, one man was at the bedside

and another was rising with a bundle in his hand from among my son’s baggage, which

was partially opened and littered over the floor. Before he could get away I sprang up and

seized him.” “There is really so little to tell. I have no doubt that

wicked Susan had planned an entrance for them. They must have known the house to an inch.

I was conscious for a moment of the chloroform rag which was thrust over my mouth, but I

have no notion how long I may have been senseless. When I woke, one man was at the bedside

and another was rising with a bundle in his hand from among my son’s baggage, which

was partially opened and littered over the floor. Before he could get away I sprang up and

seized him.”

“You took a big risk,” said the inspector. “You took a big risk,” said the inspector.

“I clung to him, but he shook me off, and the other may

have struck me, for I can remember no more. Mary the maid heard the noise and began

screaming out of the window. That brought the police, but the rascals had got away.” “I clung to him, but he shook me off, and the other may

have struck me, for I can remember no more. Mary the maid heard the noise and began

screaming out of the window. That brought the police, but the rascals had got away.”

“What did they take?” “What did they take?”

“Well, I don’t think there is anything of value

missing. I am sure there was nothing in my son’s trunks.” “Well, I don’t think there is anything of value

missing. I am sure there was nothing in my son’s trunks.”

“Did the men leave no clue?” “Did the men leave no clue?”

“There was one sheet of paper which I may have torn from

the man that I [1030]

grasped. It was lying all crumpled on the floor. It is in my son’s handwriting.” “There was one sheet of paper which I may have torn from

the man that I [1030]

grasped. It was lying all crumpled on the floor. It is in my son’s handwriting.”

“Which means that it is not of much use,” said the

inspector. “Now if it had been in the burglar’s– –” “Which means that it is not of much use,” said the

inspector. “Now if it had been in the burglar’s– –”

“Exactly,” said Holmes. “What rugged common

sense! None the less, I should be curious to see it.” “Exactly,” said Holmes. “What rugged common

sense! None the less, I should be curious to see it.”

The inspector drew a folded sheet of foolscap from his

pocketbook. The inspector drew a folded sheet of foolscap from his

pocketbook.

“I never pass anything, however trifling,” said he

with some pomposity. “That is my advice to you, Mr. Holmes. In twenty-five

years’ experience I have learned my lesson. There is always the chance of

finger-marks or something.” “I never pass anything, however trifling,” said he

with some pomposity. “That is my advice to you, Mr. Holmes. In twenty-five

years’ experience I have learned my lesson. There is always the chance of

finger-marks or something.”

Holmes inspected the sheet of paper. Holmes inspected the sheet of paper.

“What do you make of it, Inspector?” “What do you make of it, Inspector?”

“Seems to be the end of some queer novel, so far as I can

see.” “Seems to be the end of some queer novel, so far as I can

see.”

“It may certainly prove to be the end of a queer

tale,” said Holmes. “You have noticed the number on the top of the page. It is

two hundred and forty-five. Where are the odd two hundred and forty-four pages?” “It may certainly prove to be the end of a queer

tale,” said Holmes. “You have noticed the number on the top of the page. It is

two hundred and forty-five. Where are the odd two hundred and forty-four pages?”

“Well, I suppose the burglars got those. Much good may it

do them!” “Well, I suppose the burglars got those. Much good may it

do them!”

“It seems a queer thing to break into a house in order to

steal such papers as that. Does it suggest anything to you, Inspector?” “It seems a queer thing to break into a house in order to

steal such papers as that. Does it suggest anything to you, Inspector?”

“Yes, sir, it suggests that in their hurry the rascals

just grabbed at what came first to hand. I wish them joy of what they got.” “Yes, sir, it suggests that in their hurry the rascals

just grabbed at what came first to hand. I wish them joy of what they got.”

“Why should they go to my son’s things?” asked

Mrs. Maberley. “Why should they go to my son’s things?” asked

Mrs. Maberley.

“Well, they found nothing valuable downstairs, so they

tried their luck upstairs. That is how I read it. What do you make of it, Mr.

Holmes?” “Well, they found nothing valuable downstairs, so they

tried their luck upstairs. That is how I read it. What do you make of it, Mr.

Holmes?”

“I must think it over, Inspector. Come to the window,

Watson.” Then, as we stood together, he read over the fragment of paper. It began in

the middle of a sentence and ran like this: “I must think it over, Inspector. Come to the window,

Watson.” Then, as we stood together, he read over the fragment of paper. It began in

the middle of a sentence and ran like this:

“... face bled considerably from the cuts and blows,

but it was nothing to the bleeding of his heart as he saw that lovely face, the face for

which he had been prepared to sacrifice his very life, looking out at his agony and

humiliation. She smiled–yes, by Heaven! she smiled, like the heartless fiend she was,

as he looked up at her. It was at that moment that love died and hate was born. Man must

live for something. If it is not for your embrace, my lady, then it shall surely be for

your undoing and my complete revenge.” “... face bled considerably from the cuts and blows,

but it was nothing to the bleeding of his heart as he saw that lovely face, the face for

which he had been prepared to sacrifice his very life, looking out at his agony and

humiliation. She smiled–yes, by Heaven! she smiled, like the heartless fiend she was,

as he looked up at her. It was at that moment that love died and hate was born. Man must

live for something. If it is not for your embrace, my lady, then it shall surely be for

your undoing and my complete revenge.”

“Queer grammar!” said Holmes with a smile as he

handed the paper back to the inspector. “Did you notice how the ‘he’

suddenly changed to ‘my’? The writer was so carried away by his own story that

he imagined himself at the supreme moment to be the hero.” “Queer grammar!” said Holmes with a smile as he

handed the paper back to the inspector. “Did you notice how the ‘he’

suddenly changed to ‘my’? The writer was so carried away by his own story that

he imagined himself at the supreme moment to be the hero.”

“It seemed mighty poor stuff,” said the inspector as

he replaced it in his book. “What! are you off, Mr. Holmes?” “It seemed mighty poor stuff,” said the inspector as

he replaced it in his book. “What! are you off, Mr. Holmes?”

“I don’t think there is anything more for me to do

now that the case is in such capable hands. By the way, Mrs. Maberley, did you say you

wished to travel?” “I don’t think there is anything more for me to do

now that the case is in such capable hands. By the way, Mrs. Maberley, did you say you

wished to travel?”

“It has always been my dream, Mr. Holmes.” “It has always been my dream, Mr. Holmes.”

“Where would you like to go–Cairo, Madeira, the

Riviera?” “Where would you like to go–Cairo, Madeira, the

Riviera?”

“Oh, if I had the money I would go round the world.” “Oh, if I had the money I would go round the world.”

“Quite so. Round the world. Well, good-morning. I may

drop you a line in the evening.” As we passed the window I caught a glimpse of the

inspector’s smile and shake of the head. “These clever fellows have always a

touch of madness.” That was what I read in the inspector’s smile. “Quite so. Round the world. Well, good-morning. I may

drop you a line in the evening.” As we passed the window I caught a glimpse of the

inspector’s smile and shake of the head. “These clever fellows have always a

touch of madness.” That was what I read in the inspector’s smile.

[1031]

“Now, Watson, we are at the last lap of our little journey,” said Holmes when we

were back in the roar of central London once more. “I think we had best clear the

matter up at once, and it would be well that you should come with me, for it is safer to

have a witness when you are dealing with such a lady as Isadora Klein.” [1031]

“Now, Watson, we are at the last lap of our little journey,” said Holmes when we

were back in the roar of central London once more. “I think we had best clear the

matter up at once, and it would be well that you should come with me, for it is safer to

have a witness when you are dealing with such a lady as Isadora Klein.”

We had taken a cab and were speeding to some address in

Grosvenor Square. Holmes had been sunk in thought, but he roused himself suddenly. We had taken a cab and were speeding to some address in

Grosvenor Square. Holmes had been sunk in thought, but he roused himself suddenly.

“By the way, Watson, I suppose you see it all

clearly?” “By the way, Watson, I suppose you see it all

clearly?”

“No, I can’t say that I do. I only gather that we

are going to see the lady who is behind all this mischief.” “No, I can’t say that I do. I only gather that we

are going to see the lady who is behind all this mischief.”

“Exactly! But does the name Isadora Klein convey nothing

to you? She was, of course, the celebrated beauty. There was never a woman to

touch her. She is pure Spanish, the real blood of the masterful Conquistadors, and her

people have been leaders in Pernambuco for generations. She married the aged German sugar

king, Klein, and presently found herself the richest as well as the most lovely widow upon

earth. Then there was an interval of adventure when she pleased her own tastes. She had

several lovers, and Douglas Maberley, one of the most striking men in London, was one of

them. It was by all accounts more than an adventure with him. He was not a society

butterfly but a strong, proud man who gave and expected all. But she is the ‘belle

dame sans merci’ of fiction. When her caprice is satisfied the matter is ended,

and if the other party in the matter can’t take her word for it she knows how to

bring it home to him.” “Exactly! But does the name Isadora Klein convey nothing

to you? She was, of course, the celebrated beauty. There was never a woman to

touch her. She is pure Spanish, the real blood of the masterful Conquistadors, and her

people have been leaders in Pernambuco for generations. She married the aged German sugar

king, Klein, and presently found herself the richest as well as the most lovely widow upon

earth. Then there was an interval of adventure when she pleased her own tastes. She had

several lovers, and Douglas Maberley, one of the most striking men in London, was one of

them. It was by all accounts more than an adventure with him. He was not a society

butterfly but a strong, proud man who gave and expected all. But she is the ‘belle

dame sans merci’ of fiction. When her caprice is satisfied the matter is ended,

and if the other party in the matter can’t take her word for it she knows how to

bring it home to him.”

“Then that was his own story– –” “Then that was his own story– –”

“Ah! you are piecing it together now. I hear that she is

about to marry the young Duke of Lomond, who might almost be her son. His Grace’s ma

might overlook the age, but a big scandal would be a different matter, so it is

imperative– – Ah! here we are.” “Ah! you are piecing it together now. I hear that she is

about to marry the young Duke of Lomond, who might almost be her son. His Grace’s ma

might overlook the age, but a big scandal would be a different matter, so it is

imperative– – Ah! here we are.”

It was one of the finest corner-houses of the West End. A

machine-like footman took up our cards and returned with word that the lady was not at

home. “Then we shall wait until she is,” said Holmes cheerfully. It was one of the finest corner-houses of the West End. A

machine-like footman took up our cards and returned with word that the lady was not at

home. “Then we shall wait until she is,” said Holmes cheerfully.

The machine broke down. The machine broke down.

“Not at home means not at home to you,”

said the footman. “Not at home means not at home to you,”

said the footman.

“Good,” Holmes answered. “That means that we

shall not have to wait. Kindly give this note to your mistress.” “Good,” Holmes answered. “That means that we

shall not have to wait. Kindly give this note to your mistress.”

He scribbled three or four words upon a sheet of his notebook,

folded it, and handed it to the man. He scribbled three or four words upon a sheet of his notebook,

folded it, and handed it to the man.

“What did you say, Holmes?” I asked. “What did you say, Holmes?” I asked.

“I simply wrote: ‘Shall it be the police,

then?’ I think that should pass us in.” “I simply wrote: ‘Shall it be the police,

then?’ I think that should pass us in.”

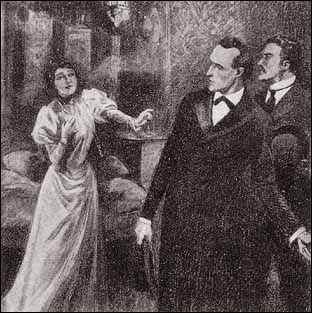

It did–with amazing celerity. A minute later we were in

an Arabian Nights drawing-room, vast and wonderful, in a half gloom, picked out with an

occasional pink electric light. The lady had come, I felt, to that time of life when even

the proudest beauty finds the half light more welcome. She rose from a settee as we

entered: tall, queenly, a perfect figure, a lovely mask-like face, with two wonderful

Spanish eyes which looked murder at us both. It did–with amazing celerity. A minute later we were in

an Arabian Nights drawing-room, vast and wonderful, in a half gloom, picked out with an

occasional pink electric light. The lady had come, I felt, to that time of life when even

the proudest beauty finds the half light more welcome. She rose from a settee as we

entered: tall, queenly, a perfect figure, a lovely mask-like face, with two wonderful

Spanish eyes which looked murder at us both.

“What is this intrusion–and this insulting

message?” she asked, holding up the slip of paper. “What is this intrusion–and this insulting

message?” she asked, holding up the slip of paper.

“I need not explain, madame. I have too much respect for

your intelligence to do so–though I confess that intelligence has been surprisingly

at fault of late.” “I need not explain, madame. I have too much respect for

your intelligence to do so–though I confess that intelligence has been surprisingly

at fault of late.”

“How so, sir?” “How so, sir?”

“By supposing that your hired bullies could frighten me

from my work. Surely [1032]

no man would take up my profession if it were not that danger attracts him. It was you,

then, who forced me to examine the case of young Maberley.” “By supposing that your hired bullies could frighten me

from my work. Surely [1032]

no man would take up my profession if it were not that danger attracts him. It was you,

then, who forced me to examine the case of young Maberley.”

“I have no idea what you are talking about. What have I

to do with hired bullies?” “I have no idea what you are talking about. What have I

to do with hired bullies?”

Holmes turned away wearily. Holmes turned away wearily.

“Yes, I have underrated your intelligence. Well,

good-afternoon!” “Yes, I have underrated your intelligence. Well,

good-afternoon!”

“Stop! Where are you going?” “Stop! Where are you going?”

“To Scotland Yard.” “To Scotland Yard.”

We had not got halfway to the door before she had overtaken us

and was holding his arm. She had turned in a moment from steel to velvet. We had not got halfway to the door before she had overtaken us

and was holding his arm. She had turned in a moment from steel to velvet.

“Come and sit down, gentlemen. Let us talk this matter

over. I feel that I may be frank with you, Mr. Holmes. You have the feelings of a

gentleman. How quick a woman’s instinct is to find it out. I will treat you as a

friend.” “Come and sit down, gentlemen. Let us talk this matter

over. I feel that I may be frank with you, Mr. Holmes. You have the feelings of a

gentleman. How quick a woman’s instinct is to find it out. I will treat you as a

friend.”

“I cannot promise to reciprocate, madame. I am not the

law, but I represent justice so far as my feeble powers go. I am ready to listen, and then

I will tell you how I will act.” “I cannot promise to reciprocate, madame. I am not the

law, but I represent justice so far as my feeble powers go. I am ready to listen, and then

I will tell you how I will act.”

“No doubt it was foolish of me to threaten a brave man

like yourself.” “No doubt it was foolish of me to threaten a brave man

like yourself.”

“What was really foolish, madame, is that you have placed

yourself in the power of a band of rascals who may blackmail or give you away.” “What was really foolish, madame, is that you have placed

yourself in the power of a band of rascals who may blackmail or give you away.”

“No, no! I am not so simple. Since I have promised to be

frank, I may say that no one, save Barney Stockdale and Susan, his wife, have the least

idea who their employer is. As to them, well, it is not the first– –” She

smiled and nodded with a charming coquettish intimacy. “No, no! I am not so simple. Since I have promised to be

frank, I may say that no one, save Barney Stockdale and Susan, his wife, have the least

idea who their employer is. As to them, well, it is not the first– –” She

smiled and nodded with a charming coquettish intimacy.

“I see. You’ve tested them before.” “I see. You’ve tested them before.”

“They are good hounds who run silent.” “They are good hounds who run silent.”

“Such hounds have a way sooner or later of biting the

hand that feeds them. They will be arrested for this burglary. The police are already

after them.” “Such hounds have a way sooner or later of biting the

hand that feeds them. They will be arrested for this burglary. The police are already

after them.”

“They will take what comes to them. That is what they are

paid for. I shall not appear in the matter.” “They will take what comes to them. That is what they are

paid for. I shall not appear in the matter.”

“Unless I bring you into it.” “Unless I bring you into it.”

“No, no, you would not. You are a gentleman. It is a

woman’s secret.” “No, no, you would not. You are a gentleman. It is a

woman’s secret.”

“In the first place, you must give back this

manuscript.” “In the first place, you must give back this

manuscript.”

She broke into a ripple of laughter and walked to the

fireplace. There was a calcined mass which she broke up with the poker. “Shall I give

this back?” she asked. So roguish and exquisite did she look as she stood before us

with a challenging smile that I felt of all Holmes’s criminals this was the one whom

he would find it hardest to face. However, he was immune from sentiment. She broke into a ripple of laughter and walked to the

fireplace. There was a calcined mass which she broke up with the poker. “Shall I give

this back?” she asked. So roguish and exquisite did she look as she stood before us

with a challenging smile that I felt of all Holmes’s criminals this was the one whom

he would find it hardest to face. However, he was immune from sentiment.

“That seals your fate,” he said coldly. “You

are very prompt in your actions, madame, but you have overdone it on this occasion.” “That seals your fate,” he said coldly. “You

are very prompt in your actions, madame, but you have overdone it on this occasion.”

She threw the poker down with a clatter. She threw the poker down with a clatter.

“How hard you are!” she cried. “May I tell you

the whole story?” “How hard you are!” she cried. “May I tell you

the whole story?”

“I fancy I could tell it to you.” “I fancy I could tell it to you.”

“But you must look at it with my eyes, Mr. Holmes. You

must realize it from the point of view of a woman who sees all her life’s ambition

about to be ruined at the last moment. Is such a woman to be blamed if she protects

herself?” “But you must look at it with my eyes, Mr. Holmes. You

must realize it from the point of view of a woman who sees all her life’s ambition

about to be ruined at the last moment. Is such a woman to be blamed if she protects

herself?”

“The original sin was yours.” “The original sin was yours.”

“Yes, yes! I admit it. He was a dear boy, Douglas, but it

so chanced that he could not fit into my plans. He wanted marriage–marriage, Mr.

Holmes– with a penniless commoner. Nothing less would serve him. Then he became

pertinacious. [1033]

Because I had given he seemed to think that I still must give, and to him only. It was

intolerable. At last I had to make him realize it.” “Yes, yes! I admit it. He was a dear boy, Douglas, but it

so chanced that he could not fit into my plans. He wanted marriage–marriage, Mr.

Holmes– with a penniless commoner. Nothing less would serve him. Then he became

pertinacious. [1033]

Because I had given he seemed to think that I still must give, and to him only. It was

intolerable. At last I had to make him realize it.”

“By hiring ruffians to beat him under your own

window.” “By hiring ruffians to beat him under your own

window.”

“You do indeed seem to know everything. Well, it is true.

Barney and the boys drove him away, and were, I admit, a little rough in doing so. But

what did he do then? Could I have believed that a gentleman would do such an act? He wrote

a book in which he described his own story. I, of course, was the wolf; he the lamb. It

was all there, under different names, of course; but who in all London would have failed

to recognize it? What do you say to that, Mr. Holmes?” “You do indeed seem to know everything. Well, it is true.

Barney and the boys drove him away, and were, I admit, a little rough in doing so. But

what did he do then? Could I have believed that a gentleman would do such an act? He wrote

a book in which he described his own story. I, of course, was the wolf; he the lamb. It

was all there, under different names, of course; but who in all London would have failed

to recognize it? What do you say to that, Mr. Holmes?”

“Well, he was within his rights.” “Well, he was within his rights.”

“It was as if the air of Italy had got into his blood and

brought with it the old cruel Italian spirit. He wrote to me and sent me a copy of his

book that I might have the torture of anticipation. There were two copies, he said

–one for me, one for his publisher.” “It was as if the air of Italy had got into his blood and

brought with it the old cruel Italian spirit. He wrote to me and sent me a copy of his

book that I might have the torture of anticipation. There were two copies, he said

–one for me, one for his publisher.”

“How did you know the publisher’s had not reached

him?” “How did you know the publisher’s had not reached

him?”

“I knew who his publisher was. It is not his only novel,

you know. I found out that he had not heard from Italy. Then came Douglas’s sudden

death. So long as that other manuscript was in the world there was no safety for me. Of

course, it must be among his effects, and these would be returned to his mother. I set the

gang at work. One of them got into the house as servant. I wanted to do the thing

honestly. I really and truly did. I was ready to buy the house and everything in it. I

offered any price she cared to ask. I only tried the other way when everything else had

failed. Now, Mr. Holmes, granting that I was too hard on Douglas–and, God knows, I am

sorry for it!–what else could I do with my whole future at stake?” “I knew who his publisher was. It is not his only novel,

you know. I found out that he had not heard from Italy. Then came Douglas’s sudden

death. So long as that other manuscript was in the world there was no safety for me. Of

course, it must be among his effects, and these would be returned to his mother. I set the

gang at work. One of them got into the house as servant. I wanted to do the thing

honestly. I really and truly did. I was ready to buy the house and everything in it. I

offered any price she cared to ask. I only tried the other way when everything else had

failed. Now, Mr. Holmes, granting that I was too hard on Douglas–and, God knows, I am

sorry for it!–what else could I do with my whole future at stake?”

Sherlock Holmes shrugged his shoulders. Sherlock Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“Well, well,” said he, “I suppose I shall have

to compound a felony as usual. How much does it cost to go round the world in first-class

style?” “Well, well,” said he, “I suppose I shall have

to compound a felony as usual. How much does it cost to go round the world in first-class

style?”

The lady stared in amazement. The lady stared in amazement.

“Could it be done on five thousand pounds?” “Could it be done on five thousand pounds?”

“Well, I should think so, indeed!” “Well, I should think so, indeed!”

“Very good. I think you will sign me a check for that,

and I will see that it comes to Mrs. Maberley. You owe her a little change of air.

Meantime, lady” –he wagged a cautionary forefinger–“have a care! Have

a care! You can’t play with edged tools forever without cutting those dainty

hands.” “Very good. I think you will sign me a check for that,

and I will see that it comes to Mrs. Maberley. You owe her a little change of air.

Meantime, lady” –he wagged a cautionary forefinger–“have a care! Have

a care! You can’t play with edged tools forever without cutting those dainty

hands.”

|

![]() The door had flown open and a huge negro had burst into the

room. He would have been a comic figure if he had not been terrific, for he was dressed in

a very loud gray check suit with a flowing salmon-coloured tie. His broad face and

flattened nose were thrust forward, as his sullen dark eyes, with a smouldering gleam of

malice in them, turned from one of us to the other.

The door had flown open and a huge negro had burst into the

room. He would have been a comic figure if he had not been terrific, for he was dressed in

a very loud gray check suit with a flowing salmon-coloured tie. His broad face and

flattened nose were thrust forward, as his sullen dark eyes, with a smouldering gleam of

malice in them, turned from one of us to the other.![]() “Which of you gen’l’men is Masser Holmes?”

he asked.

“Which of you gen’l’men is Masser Holmes?”

he asked.![]() Holmes raised his pipe with a languid smile.

Holmes raised his pipe with a languid smile.![]() “Oh! it’s you, is it?” said our visitor, coming

with an unpleasant, stealthy step round the angle of the table. “See here, Masser

Holmes, you keep your hands out of other folks’ business. Leave folks to manage their

own affairs. Got that, Masser Holmes?”

“Oh! it’s you, is it?” said our visitor, coming

with an unpleasant, stealthy step round the angle of the table. “See here, Masser

Holmes, you keep your hands out of other folks’ business. Leave folks to manage their

own affairs. Got that, Masser Holmes?”

![]() “Keep on talking,” said Holmes. “It’s

fine.”

“Keep on talking,” said Holmes. “It’s

fine.”![]() “Oh! it’s fine, is it?” growled the savage.

“It won’t be so damn fine if I have to trim you up a bit. I’ve handled your

kind before now, and they didn’t look fine when I was through with them. Look at

that, Masser Holmes!”

“Oh! it’s fine, is it?” growled the savage.

“It won’t be so damn fine if I have to trim you up a bit. I’ve handled your

kind before now, and they didn’t look fine when I was through with them. Look at

that, Masser Holmes!”![]() He swung a huge knotted lump of a fist under my friend’s

nose. Holmes examined it closely with an air of great interest. “Were you born

so?” he asked. “Or did it come by degrees?”

He swung a huge knotted lump of a fist under my friend’s

nose. Holmes examined it closely with an air of great interest. “Were you born

so?” he asked. “Or did it come by degrees?”![]() It may have been the icy coolness of my friend, or it may have

been the slight clatter which I made as I picked up the poker. In any case, our

visitor’s manner became less flamboyant.

It may have been the icy coolness of my friend, or it may have

been the slight clatter which I made as I picked up the poker. In any case, our

visitor’s manner became less flamboyant.![]() “Well, I’ve given you fair warnin’,” said

he. “I’ve a friend that’s interested out Harrow way–you know what

I’m meaning–and he don’t intend to have no buttin’ in by you. Got

that? You ain’t the law, and I ain’t the law either, and if you come in

I’ll be on hand also. Don’t you forget it.”

“Well, I’ve given you fair warnin’,” said

he. “I’ve a friend that’s interested out Harrow way–you know what

I’m meaning–and he don’t intend to have no buttin’ in by you. Got

that? You ain’t the law, and I ain’t the law either, and if you come in

I’ll be on hand also. Don’t you forget it.”![]() “I’ve wanted to meet you for some time,” said

Holmes. “I won’t ask you to sit down, for I don’t like the smell of you,

but aren’t you Steve Dixie, the bruiser?”

“I’ve wanted to meet you for some time,” said

Holmes. “I won’t ask you to sit down, for I don’t like the smell of you,

but aren’t you Steve Dixie, the bruiser?”![]() “That’s my name, Masser Holmes, and you’ll get

put through it for sure if you give me any lip.”

“That’s my name, Masser Holmes, and you’ll get

put through it for sure if you give me any lip.”![]() “It is certainly the last thing you need,” said

Holmes, staring at our visitor’s hideous mouth. “But it was the killing of young

Perkins outside the Holborn Bar– – What! you’re not going?”

“It is certainly the last thing you need,” said

Holmes, staring at our visitor’s hideous mouth. “But it was the killing of young

Perkins outside the Holborn Bar– – What! you’re not going?”![]() The negro had sprung back, and his face was leaden. “I

won’t listen to no such talk,” said he. “What have I to do with this

’ere Perkins, Masser Holmes? I was trainin’ at the Bull Ring in Birmingham when

this boy done gone get into trouble.”

The negro had sprung back, and his face was leaden. “I

won’t listen to no such talk,” said he. “What have I to do with this

’ere Perkins, Masser Holmes? I was trainin’ at the Bull Ring in Birmingham when

this boy done gone get into trouble.”![]() [1024]

“Yes, you’ll tell the magistrate about it, Steve,” said Holmes.

“I’ve been watching you and Barney Stockdale– –”

[1024]

“Yes, you’ll tell the magistrate about it, Steve,” said Holmes.

“I’ve been watching you and Barney Stockdale– –”![]() “So help me the Lord! Masser Holmes– –”

“So help me the Lord! Masser Holmes– –”![]() “That’s enough. Get out of it. I’ll pick you up

when I want you.”

“That’s enough. Get out of it. I’ll pick you up

when I want you.”![]() “Good-mornin’, Masser Holmes. I hope there

ain’t no hard feelin’s about this ’ere visit?”

“Good-mornin’, Masser Holmes. I hope there

ain’t no hard feelin’s about this ’ere visit?”![]() “There will be unless you tell me who sent you.”

“There will be unless you tell me who sent you.”![]() “Why, there ain’t no secret about that, Masser

Holmes. It was that same gen’l’man that you have just done gone mention.”

“Why, there ain’t no secret about that, Masser

Holmes. It was that same gen’l’man that you have just done gone mention.”![]() “And who set him on to it?”

“And who set him on to it?”![]() “S’elp me. I don’t know, Masser Holmes. He just

say, ‘Steve, you go see Mr. Holmes, and tell him his life ain’t safe if he go

down Harrow way.’ That’s the whole truth.” Without waiting for any further

questioning, our visitor bolted out of the room almost as precipitately as he had entered.

Holmes knocked out the ashes of his pipe with a quiet chuckle.

“S’elp me. I don’t know, Masser Holmes. He just

say, ‘Steve, you go see Mr. Holmes, and tell him his life ain’t safe if he go

down Harrow way.’ That’s the whole truth.” Without waiting for any further

questioning, our visitor bolted out of the room almost as precipitately as he had entered.

Holmes knocked out the ashes of his pipe with a quiet chuckle.![]() “I am glad you were not forced to break his woolly head,

Watson. I observed your manoeuvres with the poker. But he is really rather a harmless

fellow, a great muscular, foolish, blustering baby, and easily cowed, as you have seen. He

is one of the Spencer John gang and has taken part in some dirty work of late which I may

clear up when I have time. His immediate principal, Barney, is a more astute person. They

specialize in assaults, intimidation, and the like. What I want to know is, who is at the

back of them on this particular occasion?”

“I am glad you were not forced to break his woolly head,

Watson. I observed your manoeuvres with the poker. But he is really rather a harmless

fellow, a great muscular, foolish, blustering baby, and easily cowed, as you have seen. He

is one of the Spencer John gang and has taken part in some dirty work of late which I may

clear up when I have time. His immediate principal, Barney, is a more astute person. They

specialize in assaults, intimidation, and the like. What I want to know is, who is at the

back of them on this particular occasion?”![]() “But why do they want to intimidate you?”

“But why do they want to intimidate you?”![]() “It is this Harrow Weald case. It decides me to look into

the matter, for if it is worth anyone’s while to take so much trouble, there must be

something in it.”

“It is this Harrow Weald case. It decides me to look into

the matter, for if it is worth anyone’s while to take so much trouble, there must be

something in it.”![]() “But what is it?”

“But what is it?”![]() “I was going to tell you when we had this comic

interlude. Here is Mrs. Maberley’s note. If you care to come with me we will wire her

and go out at once.”

“I was going to tell you when we had this comic

interlude. Here is Mrs. Maberley’s note. If you care to come with me we will wire her

and go out at once.” I have had a succession of strange incidents occur to me in

connection with this house, and I should much value your advice. You would find me at home

any time to-morrow. The house is within a short walk of the Weald Station. I believe that

my late husband, Mortimer Maberley, was one of your early clients.

I have had a succession of strange incidents occur to me in

connection with this house, and I should much value your advice. You would find me at home

any time to-morrow. The house is within a short walk of the Weald Station. I believe that

my late husband, Mortimer Maberley, was one of your early clients.