|

|

“Exactly, Mr. Holmes. You amaze me. How could you

possibly know that?” “Exactly, Mr. Holmes. You amaze me. How could you

possibly know that?”

“Pray continue your very interesting statement.” “Pray continue your very interesting statement.”

“For an instant I imagined that Bannister had taken the

unpardonable liberty of examining my papers. He denied it, however, with the utmost

earnestness, and I am convinced that he was speaking the truth. The alternative was that

someone passing had observed the key in the door, had known that I was out, and had

entered to look at the papers. A large sum of money is at stake, for the scholarship is a

very valuable one, and an unscrupulous man might very well run a risk in order to gain an

advantage over his fellows. “For an instant I imagined that Bannister had taken the

unpardonable liberty of examining my papers. He denied it, however, with the utmost

earnestness, and I am convinced that he was speaking the truth. The alternative was that

someone passing had observed the key in the door, had known that I was out, and had

entered to look at the papers. A large sum of money is at stake, for the scholarship is a

very valuable one, and an unscrupulous man might very well run a risk in order to gain an

advantage over his fellows.

“Bannister was very much upset by the incident. He had

nearly fainted when we found that the papers had undoubtedly been tampered with. I gave

him a little brandy and left him collapsed in a chair, while I made a most careful

examination of the room. I soon saw that the intruder had left other traces of his

presence besides the rumpled papers. On the table in the window were several shreds from a

pencil which had been sharpened. A broken tip of lead was lying there also. Evidently the

rascal had copied the paper in a great hurry, had broken his pencil, and had been

compelled to put a fresh point to it.” “Bannister was very much upset by the incident. He had

nearly fainted when we found that the papers had undoubtedly been tampered with. I gave

him a little brandy and left him collapsed in a chair, while I made a most careful

examination of the room. I soon saw that the intruder had left other traces of his

presence besides the rumpled papers. On the table in the window were several shreds from a

pencil which had been sharpened. A broken tip of lead was lying there also. Evidently the

rascal had copied the paper in a great hurry, had broken his pencil, and had been

compelled to put a fresh point to it.”

“Excellent!” said Holmes, who was recovering his

good-humour as his attention became more engrossed by the case. “Fortune has been

your friend.” “Excellent!” said Holmes, who was recovering his

good-humour as his attention became more engrossed by the case. “Fortune has been

your friend.”

“This was not all. I have a new writing-table with a fine

surface of red leather. I am prepared to swear, and so is Bannister, that it was smooth

and unstained. Now I found a clean cut in it about three inches long–not a mere

scratch, but a positive cut. Not only this, but on the table I found a small ball of black

dough or clay, with specks of something which looks like sawdust in it. I am convinced

that these marks were left by the man who rifled the papers. There were no [598] footmarks and no other

evidence as to his identity. I was at my wit’s end, when suddenly the happy thought

occurred to me that you were in the town, and I came straight round to put the matter into

your hands. Do help me, Mr. Holmes. You see my dilemma. Either I must find the man or else

the examination must be postponed until fresh papers are prepared, and since this cannot

be done without explanation, there will ensue a hideous scandal, which will throw a cloud

not only on the college, but on the university. Above all things, I desire to settle the

matter quietly and discreetly.” “This was not all. I have a new writing-table with a fine

surface of red leather. I am prepared to swear, and so is Bannister, that it was smooth

and unstained. Now I found a clean cut in it about three inches long–not a mere

scratch, but a positive cut. Not only this, but on the table I found a small ball of black

dough or clay, with specks of something which looks like sawdust in it. I am convinced

that these marks were left by the man who rifled the papers. There were no [598] footmarks and no other

evidence as to his identity. I was at my wit’s end, when suddenly the happy thought

occurred to me that you were in the town, and I came straight round to put the matter into

your hands. Do help me, Mr. Holmes. You see my dilemma. Either I must find the man or else

the examination must be postponed until fresh papers are prepared, and since this cannot

be done without explanation, there will ensue a hideous scandal, which will throw a cloud

not only on the college, but on the university. Above all things, I desire to settle the

matter quietly and discreetly.”

“I shall be happy to look into it and to give you such

advice as I can,” said Holmes, rising and putting on his overcoat. “The case is

not entirely devoid of interest. Had anyone visited you in your room after the papers came

to you?” “I shall be happy to look into it and to give you such

advice as I can,” said Holmes, rising and putting on his overcoat. “The case is

not entirely devoid of interest. Had anyone visited you in your room after the papers came

to you?”

“Yes, young Daulat Ras, an Indian student, who lives on

the same stair, came in to ask me some particulars about the examination.” “Yes, young Daulat Ras, an Indian student, who lives on

the same stair, came in to ask me some particulars about the examination.”

“For which he was entered?” “For which he was entered?”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

“And the papers were on your table?” “And the papers were on your table?”

“To the best of my belief, they were rolled up.” “To the best of my belief, they were rolled up.”

“But might be recognized as proofs?” “But might be recognized as proofs?”

“Possibly.” “Possibly.”

“No one else in your room?” “No one else in your room?”

“No.” “No.”

“Did anyone know that these proofs would be there?” “Did anyone know that these proofs would be there?”

“No one save the printer.” “No one save the printer.”

“Did this man Bannister know?” “Did this man Bannister know?”

“No, certainly not. No one knew.” “No, certainly not. No one knew.”

“Where is Bannister now?” “Where is Bannister now?”

“He was very ill, poor fellow. I left him collapsed in

the chair. I was in such a hurry to come to you.” “He was very ill, poor fellow. I left him collapsed in

the chair. I was in such a hurry to come to you.”

“You left your door open?” “You left your door open?”

“I locked up the papers first.” “I locked up the papers first.”

“Then it amounts to this, Mr. Soames: that, unless the

Indian student recognized the roll as being proofs, the man who tampered with them came

upon them accidentally without knowing that they were there.” “Then it amounts to this, Mr. Soames: that, unless the

Indian student recognized the roll as being proofs, the man who tampered with them came

upon them accidentally without knowing that they were there.”

“So it seems to me.” “So it seems to me.”

Holmes gave an enigmatic smile. Holmes gave an enigmatic smile.

“Well,” said he, “let us go round. Not one of

your cases, Watson–mental, not physical. All right; come if you want to. Now, Mr.

Soames–at your disposal!” “Well,” said he, “let us go round. Not one of

your cases, Watson–mental, not physical. All right; come if you want to. Now, Mr.

Soames–at your disposal!”

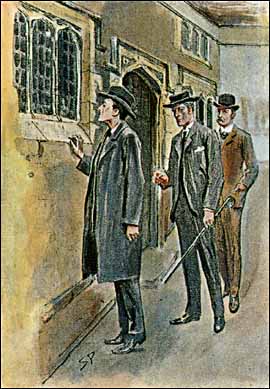

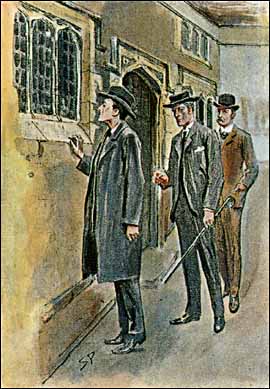

The sitting-room of our client opened by a long, low, latticed

window on to the ancient lichen-tinted court of the old college. A Gothic arched door led

to a worn stone staircase. On the ground floor was the tutor’s room. Above were three

students, one on each story. It was already twilight when we reached the scene of our

problem. Holmes halted and looked earnestly at the window. Then he approached it, and,

standing on tiptoe with his neck craned, he looked into the room. The sitting-room of our client opened by a long, low, latticed

window on to the ancient lichen-tinted court of the old college. A Gothic arched door led

to a worn stone staircase. On the ground floor was the tutor’s room. Above were three

students, one on each story. It was already twilight when we reached the scene of our

problem. Holmes halted and looked earnestly at the window. Then he approached it, and,

standing on tiptoe with his neck craned, he looked into the room.

“He must have entered through the door. There is no

opening except the one pane,” said our learned guide. “He must have entered through the door. There is no

opening except the one pane,” said our learned guide.

“Dear me!” said Holmes, and he smiled in a singular

way as he glanced at our companion. “Well, if there is nothing to be learned here, we

had best go inside.” “Dear me!” said Holmes, and he smiled in a singular

way as he glanced at our companion. “Well, if there is nothing to be learned here, we

had best go inside.”

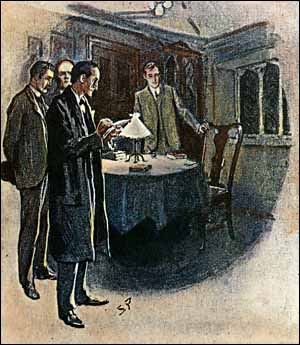

[599] The

lecturer unlocked the outer door and ushered us into his room. We stood at the entrance

while Holmes made an examination of the carpet. [599] The

lecturer unlocked the outer door and ushered us into his room. We stood at the entrance

while Holmes made an examination of the carpet.

“I am afraid there are no signs here,” said he.

“One could hardly hope for any upon so dry a day. Your servant seems to have quite

recovered. You left him in a chair, you say. Which chair?” “I am afraid there are no signs here,” said he.

“One could hardly hope for any upon so dry a day. Your servant seems to have quite

recovered. You left him in a chair, you say. Which chair?”

“By the window there.” “By the window there.”

“I see. Near this little table. You can come in now. I

have finished with the carpet. Let us take the little table first. Of course, what has

happened is very clear. The man entered and took the papers, sheet by sheet, from the

central table. He carried them over to the window table, because from there he could see

if you came across the courtyard, and so could effect an escape.” “I see. Near this little table. You can come in now. I

have finished with the carpet. Let us take the little table first. Of course, what has

happened is very clear. The man entered and took the papers, sheet by sheet, from the

central table. He carried them over to the window table, because from there he could see

if you came across the courtyard, and so could effect an escape.”

“As a matter of fact, he could not,” said Soames,

“for I entered by the side door.” “As a matter of fact, he could not,” said Soames,

“for I entered by the side door.”

“Ah, that’s good! Well, anyhow, that was in his

mind. Let me see the three strips. No finger impressions–no! Well, he carried over

this one first, and he copied it. How long would it take him to do that, using every

possible contraction? A quarter of an hour, not less. Then he tossed it down and seized

the next. He was in the midst of that when your return caused him to make a very hurried

retreat–very hurried, since he had not time to replace the papers which would tell

you that he had been there. You were not aware of any hurrying feet on the stair as you

entered the outer door?” “Ah, that’s good! Well, anyhow, that was in his

mind. Let me see the three strips. No finger impressions–no! Well, he carried over

this one first, and he copied it. How long would it take him to do that, using every

possible contraction? A quarter of an hour, not less. Then he tossed it down and seized

the next. He was in the midst of that when your return caused him to make a very hurried

retreat–very hurried, since he had not time to replace the papers which would tell

you that he had been there. You were not aware of any hurrying feet on the stair as you

entered the outer door?”

“No, I can’t say I was.” “No, I can’t say I was.”

“Well, he wrote so furiously that he broke his pencil,

and had, as you observe, to sharpen it again. This is of interest, Watson. The pencil was

not an ordinary one. It was above the usual size, with a soft lead, the outer colour was

dark blue, the maker’s name was printed in silver lettering, and the piece remaining

is only about an inch and a half long. Look for such a pencil, Mr. Soames, and you have

got your man. When I add that he possesses a large and very blunt knife, you have an

additional aid.” “Well, he wrote so furiously that he broke his pencil,

and had, as you observe, to sharpen it again. This is of interest, Watson. The pencil was

not an ordinary one. It was above the usual size, with a soft lead, the outer colour was

dark blue, the maker’s name was printed in silver lettering, and the piece remaining

is only about an inch and a half long. Look for such a pencil, Mr. Soames, and you have

got your man. When I add that he possesses a large and very blunt knife, you have an

additional aid.”

Mr. Soames was somewhat overwhelmed by this flood of

information. “I can follow the other points,” said he, “but really, in this

matter of the length– –” Mr. Soames was somewhat overwhelmed by this flood of

information. “I can follow the other points,” said he, “but really, in this

matter of the length– –”

Holmes held out a small chip with the letters NN and a space

of clear wood after them. Holmes held out a small chip with the letters NN and a space

of clear wood after them.

“You see?” “You see?”

“No, I fear that even now– –” “No, I fear that even now– –”

“Watson, I have always done you an injustice. There are

others. What could this NN be? It is at the end of a word. You are aware that Johann Faber

is the most common maker’s name. Is it not clear that there is just as much of the

pencil left as usually follows the Johann?” He held the small table sideways to the

electric light. “I was hoping that if the paper on which he wrote was thin, some

trace of it might come through upon this polished surface. No, I see nothing. I don’t

think there is anything more to be learned here. Now for the central table. This small

pellet is, I presume, the black, doughy mass you spoke of. Roughly pyramidal in shape and

hollowed out, I perceive. As you say, there appear to be grains of sawdust in it. Dear me,

this is very interesting. And the cut–a positive tear, I see. It began with a thin

scratch and ended in a jagged hole. I am much indebted to you for directing my attention

to this case, Mr. Soames. Where does that door lead to?” “Watson, I have always done you an injustice. There are

others. What could this NN be? It is at the end of a word. You are aware that Johann Faber

is the most common maker’s name. Is it not clear that there is just as much of the

pencil left as usually follows the Johann?” He held the small table sideways to the

electric light. “I was hoping that if the paper on which he wrote was thin, some

trace of it might come through upon this polished surface. No, I see nothing. I don’t

think there is anything more to be learned here. Now for the central table. This small

pellet is, I presume, the black, doughy mass you spoke of. Roughly pyramidal in shape and

hollowed out, I perceive. As you say, there appear to be grains of sawdust in it. Dear me,

this is very interesting. And the cut–a positive tear, I see. It began with a thin

scratch and ended in a jagged hole. I am much indebted to you for directing my attention

to this case, Mr. Soames. Where does that door lead to?”

“To my bedroom.” “To my bedroom.”

[600] “Have

you been in it since your adventure?” [600] “Have

you been in it since your adventure?”

“No, I came straight away for you.” “No, I came straight away for you.”

“I should like to have a glance round. What a charming,

old-fashioned room! Perhaps you will kindly wait a minute, until I have examined the

floor. No, I see nothing. What about this curtain? You hang your clothes behind it. If

anyone were forced to conceal himself in this room he must do it there, since the bed is

too low and the wardrobe too shallow. No one there, I suppose?” “I should like to have a glance round. What a charming,

old-fashioned room! Perhaps you will kindly wait a minute, until I have examined the

floor. No, I see nothing. What about this curtain? You hang your clothes behind it. If

anyone were forced to conceal himself in this room he must do it there, since the bed is

too low and the wardrobe too shallow. No one there, I suppose?”

As Holmes drew the curtain I was aware, from some little

rigidity and alertness of his attitude, that he was prepared for an emergency. As a matter

of fact, the drawn curtain disclosed nothing but three or four suits of clothes hanging

from a line of pegs. Holmes turned away, and stooped suddenly to the floor. As Holmes drew the curtain I was aware, from some little

rigidity and alertness of his attitude, that he was prepared for an emergency. As a matter

of fact, the drawn curtain disclosed nothing but three or four suits of clothes hanging

from a line of pegs. Holmes turned away, and stooped suddenly to the floor.

“Halloa! What’s this?” said he. “Halloa! What’s this?” said he.

It was a small pyramid of black, putty-like stuff, exactly

like the one upon the table of the study. Holmes held it out on his open palm in the glare

of the electric light. It was a small pyramid of black, putty-like stuff, exactly

like the one upon the table of the study. Holmes held it out on his open palm in the glare

of the electric light.

“Your visitor seems to have left traces in your bedroom

as well as in your sitting-room, Mr. Soames.” “Your visitor seems to have left traces in your bedroom

as well as in your sitting-room, Mr. Soames.”

“What could he have wanted there?” “What could he have wanted there?”

“I think it is clear enough. You came back by an

unexpected way, and so he had no warning until you were at the very door. What could he

do? He caught up everything which would betray him, and he rushed into your bedroom to

conceal himself.” “I think it is clear enough. You came back by an

unexpected way, and so he had no warning until you were at the very door. What could he

do? He caught up everything which would betray him, and he rushed into your bedroom to

conceal himself.”

“Good gracious, Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that,

all the time I was talking to Bannister in this room, we had the man prisoner if we had

only known it?” “Good gracious, Mr. Holmes, do you mean to tell me that,

all the time I was talking to Bannister in this room, we had the man prisoner if we had

only known it?”

“So I read it.” “So I read it.”

“Surely there is another alternative, Mr. Holmes. I

don’t know whether you observed my bedroom window?” “Surely there is another alternative, Mr. Holmes. I

don’t know whether you observed my bedroom window?”

“Lattice-paned, lead framework, three separate windows,

one swinging on hinge, and large enough to admit a man.” “Lattice-paned, lead framework, three separate windows,

one swinging on hinge, and large enough to admit a man.”

“Exactly. And it looks out on an angle of the courtyard

so as to be partly invisible. The man might have effected his entrance there, left traces

as he passed through the bedroom, and finally, finding the door open, have escaped that

way.” “Exactly. And it looks out on an angle of the courtyard

so as to be partly invisible. The man might have effected his entrance there, left traces

as he passed through the bedroom, and finally, finding the door open, have escaped that

way.”

Holmes shook his head impatiently. Holmes shook his head impatiently.

“Let us be practical,” said he. “I understand

you to say that there are three students who use this stair, and are in the habit of

passing your door?” “Let us be practical,” said he. “I understand

you to say that there are three students who use this stair, and are in the habit of

passing your door?”

“Yes, there are.” “Yes, there are.”

“And they are all in for this examination?” “And they are all in for this examination?”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

“Have you any reason to suspect any one of them more than

the others?” “Have you any reason to suspect any one of them more than

the others?”

Soames hesitated. Soames hesitated.

“It is a very delicate question,” said he. “One

hardly likes to throw suspicion where there are no proofs.” “It is a very delicate question,” said he. “One

hardly likes to throw suspicion where there are no proofs.”

“Let us hear the suspicions. I will look after the

proofs.” “Let us hear the suspicions. I will look after the

proofs.”

“I will tell you, then, in a few words the character of

the three men who inhabit these rooms. The lower of the three is Gilchrist, a fine scholar

and athlete, plays in the Rugby team and the cricket team for the college, and got his

Blue for the hurdles and the long jump. He is a fine, manly fellow. His father was the

notorious Sir Jabez Gilchrist, who ruined himself on the turf. My scholar has been left

very poor, but he is hard-working and industrious. He will do well. “I will tell you, then, in a few words the character of

the three men who inhabit these rooms. The lower of the three is Gilchrist, a fine scholar

and athlete, plays in the Rugby team and the cricket team for the college, and got his

Blue for the hurdles and the long jump. He is a fine, manly fellow. His father was the

notorious Sir Jabez Gilchrist, who ruined himself on the turf. My scholar has been left

very poor, but he is hard-working and industrious. He will do well.

[601] “The

second floor is inhabited by Daulat Ras, the Indian. He is a quiet, inscrutable fellow; as

most of those Indians are. He is well up in his work, though his Greek is his weak

subject. He is steady and methodical. [601] “The

second floor is inhabited by Daulat Ras, the Indian. He is a quiet, inscrutable fellow; as

most of those Indians are. He is well up in his work, though his Greek is his weak

subject. He is steady and methodical.

“The top floor belongs to Miles McLaren. He is a

brilliant fellow when he chooses to work–one of the brightest intellects of the

university; but he is wayward, dissipated, and unprincipled. He was nearly expelled over a

card scandal in his first year. He has been idling all this term, and he must look forward

with dread to the examination.” “The top floor belongs to Miles McLaren. He is a

brilliant fellow when he chooses to work–one of the brightest intellects of the

university; but he is wayward, dissipated, and unprincipled. He was nearly expelled over a

card scandal in his first year. He has been idling all this term, and he must look forward

with dread to the examination.”

“Then it is he whom you suspect?” “Then it is he whom you suspect?”

“I dare not go so far as that. But, of the three, he is

perhaps the least unlikely.” “I dare not go so far as that. But, of the three, he is

perhaps the least unlikely.”

“Exactly. Now, Mr. Soames, let us have a look at your

servant, Bannister.” “Exactly. Now, Mr. Soames, let us have a look at your

servant, Bannister.”

He was a little, white-faced, clean-shaven, grizzly-haired

fellow of fifty. He was still suffering from this sudden disturbance of the quiet routine

of his life. His plump face was twitching with his nervousness, and his fingers could not

keep still. He was a little, white-faced, clean-shaven, grizzly-haired

fellow of fifty. He was still suffering from this sudden disturbance of the quiet routine

of his life. His plump face was twitching with his nervousness, and his fingers could not

keep still.

“We are investigating this unhappy business,

Bannister,” said his master. “We are investigating this unhappy business,

Bannister,” said his master.

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“I understand,” said Holmes, “that you left

your key in the door?” “I understand,” said Holmes, “that you left

your key in the door?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“Was it not very extraordinary that you should do this on

the very day when there were these papers inside?” “Was it not very extraordinary that you should do this on

the very day when there were these papers inside?”

“It was most unfortunate, sir. But I have occasionally

done the same thing at other times.” “It was most unfortunate, sir. But I have occasionally

done the same thing at other times.”

“When did you enter the room?” “When did you enter the room?”

“It was about half-past four. That is Mr. Soames’

tea time.” “It was about half-past four. That is Mr. Soames’

tea time.”

“How long did you stay?” “How long did you stay?”

“When I saw that he was absent, I withdrew at once.” “When I saw that he was absent, I withdrew at once.”

“Did you look at these papers on the table?” “Did you look at these papers on the table?”

“No, sir–certainly not.” “No, sir–certainly not.”

“How came you to leave the key in the door?” “How came you to leave the key in the door?”

“I had the tea-tray in my hand. I thought I would come

back for the key. Then I forgot.” “I had the tea-tray in my hand. I thought I would come

back for the key. Then I forgot.”

“Has the outer door a spring lock?” “Has the outer door a spring lock?”

“No, sir.” “No, sir.”

“Then it was open all the time?” “Then it was open all the time?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“Anyone in the room could get out?” “Anyone in the room could get out?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“When Mr. Soames returned and called for you, you were

very much disturbed?” “When Mr. Soames returned and called for you, you were

very much disturbed?”

“Yes, sir. Such a thing has never happened during the

many years that I have been here. I nearly fainted, sir.” “Yes, sir. Such a thing has never happened during the

many years that I have been here. I nearly fainted, sir.”

“So I understand. Where were you when you began to feel

bad?” “So I understand. Where were you when you began to feel

bad?”

“Where was I, sir? Why, here, near the door.” “Where was I, sir? Why, here, near the door.”

“That is singular, because you sat down in that chair

over yonder near the corner. Why did you pass these other chairs?” “That is singular, because you sat down in that chair

over yonder near the corner. Why did you pass these other chairs?”

“I don’t know, sir, it didn’t matter to me

where I sat.” “I don’t know, sir, it didn’t matter to me

where I sat.”

“I really don’t think he knew much about it, Mr.

Holmes. He was looking very bad–quite ghastly.” “I really don’t think he knew much about it, Mr.

Holmes. He was looking very bad–quite ghastly.”

“You stayed here when your master left?” “You stayed here when your master left?”

“Only for a minute or so. Then I locked the door and went

to my room.” “Only for a minute or so. Then I locked the door and went

to my room.”

[602] “Whom

do you suspect?” [602] “Whom

do you suspect?”

“Oh, I would not venture to say, sir. I don’t

believe there is any gentleman in this university who is capable of profiting by such an

action. No, sir, I’ll not believe it.” “Oh, I would not venture to say, sir. I don’t

believe there is any gentleman in this university who is capable of profiting by such an

action. No, sir, I’ll not believe it.”

“Thank you, that will do,” said Holmes. “Oh,

one more word. You have not mentioned to any of the three gentlemen whom you attend that

anything is amiss?” “Thank you, that will do,” said Holmes. “Oh,

one more word. You have not mentioned to any of the three gentlemen whom you attend that

anything is amiss?”

“No, sir–not a word.” “No, sir–not a word.”

“You haven’t seen any of them?” “You haven’t seen any of them?”

“No, sir.” “No, sir.”

“Very good. Now, Mr. Soames, we will take a walk in the

quadrangle, if you please.” “Very good. Now, Mr. Soames, we will take a walk in the

quadrangle, if you please.”

Three yellow squares of light shone above us in the gathering

gloom. Three yellow squares of light shone above us in the gathering

gloom.

“Your three birds are all in their nests,” said

Holmes, looking up. “Halloa! What’s that? One of them seems restless

enough.” “Your three birds are all in their nests,” said

Holmes, looking up. “Halloa! What’s that? One of them seems restless

enough.”

It was the Indian, whose dark silhouette appeared suddenly

upon his blind. He was pacing swiftly up and down his room. It was the Indian, whose dark silhouette appeared suddenly

upon his blind. He was pacing swiftly up and down his room.

“I should like to have a peep at each of them,” said

Holmes. “Is it possible?” “I should like to have a peep at each of them,” said

Holmes. “Is it possible?”

“No difficulty in the world,” Soames answered.

“This set of rooms is quite the oldest in the college, and it is not unusual for

visitors to go over them. Come along, and I will personally conduct you.” “No difficulty in the world,” Soames answered.

“This set of rooms is quite the oldest in the college, and it is not unusual for

visitors to go over them. Come along, and I will personally conduct you.”

“No names, please!” said Holmes, as we knocked at

Gilchrist’s door. A tall, flaxen-haired, slim young fellow opened it, and made us

welcome when he understood our errand. There were some really curious pieces of mediaeval

domestic architecture within. Holmes was so charmed with one of them that he insisted on

drawing it in his notebook, broke his pencil, had to borrow one from our host, and finally

borrowed a knife to sharpen his own. The same curious accident happened to him in the

rooms of the Indian–a silent, little, hook-nosed fellow, who eyed us askance, and was

obviously glad when Holmes’s architectural studies had come to an end. I could not

see that in either case Holmes had come upon the clue for which he was searching. Only at

the third did our visit prove abortive. The outer door would not open to our knock, and

nothing more substantial than a torrent of bad language came from behind it. “I

don’t care who you are. You can go to blazes!” roared the angry voice.

“To-morrow’s the exam, and I won’t be drawn by anyone.” “No names, please!” said Holmes, as we knocked at

Gilchrist’s door. A tall, flaxen-haired, slim young fellow opened it, and made us

welcome when he understood our errand. There were some really curious pieces of mediaeval

domestic architecture within. Holmes was so charmed with one of them that he insisted on

drawing it in his notebook, broke his pencil, had to borrow one from our host, and finally

borrowed a knife to sharpen his own. The same curious accident happened to him in the

rooms of the Indian–a silent, little, hook-nosed fellow, who eyed us askance, and was

obviously glad when Holmes’s architectural studies had come to an end. I could not

see that in either case Holmes had come upon the clue for which he was searching. Only at

the third did our visit prove abortive. The outer door would not open to our knock, and

nothing more substantial than a torrent of bad language came from behind it. “I

don’t care who you are. You can go to blazes!” roared the angry voice.

“To-morrow’s the exam, and I won’t be drawn by anyone.”

“A rude fellow,” said our guide, flushing with anger

as we withdrew down the stair. “Of course, he did not realize that it was I who was

knocking, but none the less his conduct was very uncourteous, and, indeed, under the

circumstances rather suspicious.” “A rude fellow,” said our guide, flushing with anger

as we withdrew down the stair. “Of course, he did not realize that it was I who was

knocking, but none the less his conduct was very uncourteous, and, indeed, under the

circumstances rather suspicious.”

Holmes’s response was a curious one. Holmes’s response was a curious one.

“Can you tell me his exact height?” he asked. “Can you tell me his exact height?” he asked.

“Really, Mr. Holmes, I cannot undertake to say. He is

taller than the Indian, not so tall as Gilchrist. I suppose five foot six would be about

it.” “Really, Mr. Holmes, I cannot undertake to say. He is

taller than the Indian, not so tall as Gilchrist. I suppose five foot six would be about

it.”

“That is very important,” said Holmes. “And

now, Mr. Soames, I wish you good-night.” “That is very important,” said Holmes. “And

now, Mr. Soames, I wish you good-night.”

Our guide cried aloud in his astonishment and dismay.

“Good gracious, Mr. Holmes, you are surely not going to leave me in this abrupt

fashion! You don’t seem to realize the position. To-morrow is the examination. I must

take some definite action to-night. I cannot allow the examination to be held if one of

the papers has been tampered with. The situation must be faced.” Our guide cried aloud in his astonishment and dismay.

“Good gracious, Mr. Holmes, you are surely not going to leave me in this abrupt

fashion! You don’t seem to realize the position. To-morrow is the examination. I must

take some definite action to-night. I cannot allow the examination to be held if one of

the papers has been tampered with. The situation must be faced.”

[603] “You

must leave it as it is. I shall drop round early to-morrow morning and chat the matter

over. It is possible that I may be in a position then to indicate some course of action.

Meanwhile, you change nothing–nothing at all.” [603] “You

must leave it as it is. I shall drop round early to-morrow morning and chat the matter

over. It is possible that I may be in a position then to indicate some course of action.

Meanwhile, you change nothing–nothing at all.”

“Very good, Mr. Holmes.” “Very good, Mr. Holmes.”

“You can be perfectly easy in your mind. We shall

certainly find some way out of your difficulties. I will take the black clay with me, also

the pencil cuttings. Good-bye.” “You can be perfectly easy in your mind. We shall

certainly find some way out of your difficulties. I will take the black clay with me, also

the pencil cuttings. Good-bye.”

When we were out in the darkness of the quadrangle, we again

looked up at the windows. The Indian still paced his room. The others were invisible. When we were out in the darkness of the quadrangle, we again

looked up at the windows. The Indian still paced his room. The others were invisible.

“Well, Watson, what do you think of it?” Holmes

asked, as we came out into the main street. “Quite a little parlour game–sort of

three-card trick, is it not? There are your three men. It must be one of them. You take

your choice. Which is yours?” “Well, Watson, what do you think of it?” Holmes

asked, as we came out into the main street. “Quite a little parlour game–sort of

three-card trick, is it not? There are your three men. It must be one of them. You take

your choice. Which is yours?”

“The foul-mouthed fellow at the top. He is the one with

the worst record. And yet that Indian was a sly fellow also. Why should he be pacing his

room all the time?” “The foul-mouthed fellow at the top. He is the one with

the worst record. And yet that Indian was a sly fellow also. Why should he be pacing his

room all the time?”

“There is nothing in that. Many men do it when they are

trying to learn anything by heart.” “There is nothing in that. Many men do it when they are

trying to learn anything by heart.”

“He looked at us in a queer way.” “He looked at us in a queer way.”

“So would you, if a flock of strangers came in on you

when you were preparing for an examination next day, and every moment was of value. No, I

see nothing in that. Pencils, too, and knives–all was satisfactory. But that fellow

does puzzle me.” “So would you, if a flock of strangers came in on you

when you were preparing for an examination next day, and every moment was of value. No, I

see nothing in that. Pencils, too, and knives–all was satisfactory. But that fellow

does puzzle me.”

“Who?” “Who?”

“Why, Bannister, the servant. What’s his game in the

matter?” “Why, Bannister, the servant. What’s his game in the

matter?”

“He impressed me as being a perfectly honest man.” “He impressed me as being a perfectly honest man.”

“So he did me. That’s the puzzling part. Why should

a perfectly honest man– – Well, well, here’s a large stationer’s. We

shall begin our researches here.” “So he did me. That’s the puzzling part. Why should

a perfectly honest man– – Well, well, here’s a large stationer’s. We

shall begin our researches here.”

There were only four stationers of any consequences in the

town, and at each Holmes produced his pencil chips, and bid high for a duplicate. All were

agreed that one could be ordered, but that it was not a usual size of pencil, and that it

was seldom kept in stock. My friend did not appear to be depressed by his failure, but

shrugged his shoulders in half-humorous resignation. There were only four stationers of any consequences in the

town, and at each Holmes produced his pencil chips, and bid high for a duplicate. All were

agreed that one could be ordered, but that it was not a usual size of pencil, and that it

was seldom kept in stock. My friend did not appear to be depressed by his failure, but

shrugged his shoulders in half-humorous resignation.

“No good, my dear Watson. This, the best and only final

clue, has run to nothing. But, indeed, I have little doubt that we can build up a

sufficient case without it. By Jove! my dear fellow, it is nearly nine, and the landlady

babbled of green peas at seven-thirty. What with your eternal tobacco, Watson, and your

irregularity at meals, I expect that you will get notice to quit, and that I shall share

your downfall–not, however, before we have solved the problem of the nervous tutor,

the careless servant, and the three enterprising students.” “No good, my dear Watson. This, the best and only final

clue, has run to nothing. But, indeed, I have little doubt that we can build up a

sufficient case without it. By Jove! my dear fellow, it is nearly nine, and the landlady

babbled of green peas at seven-thirty. What with your eternal tobacco, Watson, and your

irregularity at meals, I expect that you will get notice to quit, and that I shall share

your downfall–not, however, before we have solved the problem of the nervous tutor,

the careless servant, and the three enterprising students.”

Holmes made no further allusion to the matter that day, though

he sat lost in thought for a long time after our belated dinner. At eight in the morning,

he came into my room just as I finished my toilet. Holmes made no further allusion to the matter that day, though

he sat lost in thought for a long time after our belated dinner. At eight in the morning,

he came into my room just as I finished my toilet.

“Well, Watson,” said he, “it is time we went

down to St. Luke’s. Can you do without breakfast?” “Well, Watson,” said he, “it is time we went

down to St. Luke’s. Can you do without breakfast?”

“Certainly.” “Certainly.”

“Soames will be in a dreadful fidget until we are able to

tell him something positive.” “Soames will be in a dreadful fidget until we are able to

tell him something positive.”

“Have you anything positive to tell him?” “Have you anything positive to tell him?”

“I think so.” “I think so.”

[604] “You

have formed a conclusion?” [604] “You

have formed a conclusion?”

“Yes, my dear Watson, I have solved the mystery.” “Yes, my dear Watson, I have solved the mystery.”

“But what fresh evidence could you have got?” “But what fresh evidence could you have got?”

“Aha! It is not for nothing that I have turned myself out

of bed at the untimely hour of six. I have put in two hours’ hard work and covered at

least five miles, with something to show for it. Look at that!” “Aha! It is not for nothing that I have turned myself out

of bed at the untimely hour of six. I have put in two hours’ hard work and covered at

least five miles, with something to show for it. Look at that!”

He held out his hand. On the palm were three little pyramids

of black, doughy clay. He held out his hand. On the palm were three little pyramids

of black, doughy clay.

“Why, Holmes, you had only two yesterday.” “Why, Holmes, you had only two yesterday.”

“And one more this morning. It is a fair argument that

wherever No. 3 came from is also the source of Nos. 1 and 2. Eh, Watson? Well, come along

and put friend Soames out of his pain.” “And one more this morning. It is a fair argument that

wherever No. 3 came from is also the source of Nos. 1 and 2. Eh, Watson? Well, come along

and put friend Soames out of his pain.”

The unfortunate tutor was certainly in a state of pitiable

agitation when we found him in his chambers. In a few hours the examination would

commence, and he was still in the dilemma between making the facts public and allowing the

culprit to compete for the valuable scholarship. He could hardly stand still, so great was

his mental agitation, and he ran towards Holmes with two eager hands outstretched. The unfortunate tutor was certainly in a state of pitiable

agitation when we found him in his chambers. In a few hours the examination would

commence, and he was still in the dilemma between making the facts public and allowing the

culprit to compete for the valuable scholarship. He could hardly stand still, so great was

his mental agitation, and he ran towards Holmes with two eager hands outstretched.

“Thank heaven that you have come! I feared that you had

given it up in despair. What am I to do? Shall the examination proceed?” “Thank heaven that you have come! I feared that you had

given it up in despair. What am I to do? Shall the examination proceed?”

“Yes, let it proceed, by all means.” “Yes, let it proceed, by all means.”

“But this rascal?” “But this rascal?”

“He shall not compete.” “He shall not compete.”

“You know him?” “You know him?”

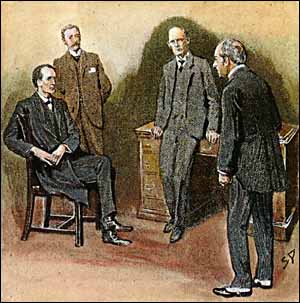

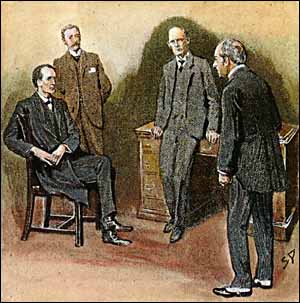

“I think so. If this matter is not to become public, we

must give ourselves certain powers and resolve ourselves into a small private

court-martial. You there, if you please, Soames! Watson, you here! I’ll take the

armchair in the middle. I think that we are now sufficiently imposing to strike terror

into a guilty breast. Kindly ring the bell!” “I think so. If this matter is not to become public, we

must give ourselves certain powers and resolve ourselves into a small private

court-martial. You there, if you please, Soames! Watson, you here! I’ll take the

armchair in the middle. I think that we are now sufficiently imposing to strike terror

into a guilty breast. Kindly ring the bell!”

Bannister entered, and shrank back in evident surprise and

fear at our judicial appearance. Bannister entered, and shrank back in evident surprise and

fear at our judicial appearance.

“You will kindly close the door,” said Holmes.

“Now, Bannister, will you please tell us the truth about yesterday’s

incident?” “You will kindly close the door,” said Holmes.

“Now, Bannister, will you please tell us the truth about yesterday’s

incident?”

The man turned white to the roots of his hair. The man turned white to the roots of his hair.

“I have told you everything, sir.” “I have told you everything, sir.”

“Nothing to add?” “Nothing to add?”

“Nothing at all, sir.” “Nothing at all, sir.”

“Well, then, I must make some suggestions to you. When

you sat down on that chair yesterday, did you do so in order to conceal some object which

would have shown who had been in the room?” “Well, then, I must make some suggestions to you. When

you sat down on that chair yesterday, did you do so in order to conceal some object which

would have shown who had been in the room?”

Bannister’s face was ghastly. Bannister’s face was ghastly.

“No, sir, certainly not.” “No, sir, certainly not.”

“It is only a suggestion,” said Holmes, suavely.

“I frankly admit that I am unable to prove it. But it seems probable enough, since

the moment that Mr. Soames’s back was turned, you released the man who was hiding in

that bedroom.” “It is only a suggestion,” said Holmes, suavely.

“I frankly admit that I am unable to prove it. But it seems probable enough, since

the moment that Mr. Soames’s back was turned, you released the man who was hiding in

that bedroom.”

Bannister licked his dry lips. Bannister licked his dry lips.

“There was no man, sir.” “There was no man, sir.”

“Ah, that’s a pity, Bannister. Up to now you may

have spoken the truth, but now I know that you have lied.” “Ah, that’s a pity, Bannister. Up to now you may

have spoken the truth, but now I know that you have lied.”

[605] The

man’s face set in sullen defiance. [605] The

man’s face set in sullen defiance.

“There was no man, sir.” “There was no man, sir.”

“Come, come, Bannister!” “Come, come, Bannister!”

“No, sir, there was no one.” “No, sir, there was no one.”

“In that case, you can give us no further information.

Would you please remain in the room? Stand over there near the bedroom door. Now, Soames,

I am going to ask you to have the great kindness to go up to the room of young Gilchrist,

and to ask him to step down into yours.” “In that case, you can give us no further information.

Would you please remain in the room? Stand over there near the bedroom door. Now, Soames,

I am going to ask you to have the great kindness to go up to the room of young Gilchrist,

and to ask him to step down into yours.”

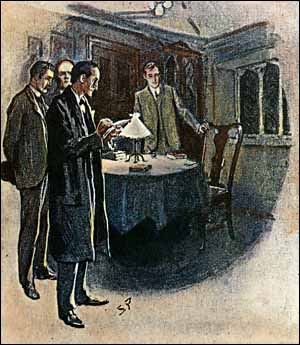

An instant later the tutor returned, bringing with him the

student. He was a fine figure of a man, tall, lithe, and agile, with a springy step and a

pleasant, open face. His troubled blue eyes glanced at each of us, and finally rested with

an expression of blank dismay upon Bannister in the farther corner. An instant later the tutor returned, bringing with him the

student. He was a fine figure of a man, tall, lithe, and agile, with a springy step and a

pleasant, open face. His troubled blue eyes glanced at each of us, and finally rested with

an expression of blank dismay upon Bannister in the farther corner.

“Just close the door,” said Holmes. “Now,

Mr. Gilchrist, we are all quite alone here, and no one need ever know one word of what

passes between us. We can be perfectly frank with each other. We want to know, Mr.

Gilchrist, how you, an honourable man, ever came to commit such an action as that of

yesterday?” “Just close the door,” said Holmes. “Now,

Mr. Gilchrist, we are all quite alone here, and no one need ever know one word of what

passes between us. We can be perfectly frank with each other. We want to know, Mr.

Gilchrist, how you, an honourable man, ever came to commit such an action as that of

yesterday?”

The unfortunate young man staggered back, and cast a look full

of horror and reproach at Bannister. The unfortunate young man staggered back, and cast a look full

of horror and reproach at Bannister.

“No, no, Mr. Gilchrist, sir, I never said a

word–never one word!” cried the servant. “No, no, Mr. Gilchrist, sir, I never said a

word–never one word!” cried the servant.

“No, but you have now,” said Holmes. “Now, sir,

you must see that after Bannister’s words your position is hopeless, and that your

only chance lies in a frank confession.” “No, but you have now,” said Holmes. “Now, sir,

you must see that after Bannister’s words your position is hopeless, and that your

only chance lies in a frank confession.”

For a moment Gilchrist, with upraised hand, tried to

control his writhing features. The next he had thrown himself on his knees beside the

table, and burying his face in his hands, he had burst into a storm of passionate sobbing. For a moment Gilchrist, with upraised hand, tried to

control his writhing features. The next he had thrown himself on his knees beside the

table, and burying his face in his hands, he had burst into a storm of passionate sobbing.

“Come, come,” said Holmes, kindly, “it is human

to err, and at least no one can accuse you of being a callous criminal. Perhaps it would

be easier for you if I were to tell Mr. Soames what occurred, and you can check me where I

am wrong. Shall I do so? Well, well, don’t trouble to answer. Listen, and see that I

do you no injustice. “Come, come,” said Holmes, kindly, “it is human

to err, and at least no one can accuse you of being a callous criminal. Perhaps it would

be easier for you if I were to tell Mr. Soames what occurred, and you can check me where I

am wrong. Shall I do so? Well, well, don’t trouble to answer. Listen, and see that I

do you no injustice.

“From the moment, Mr. Soames, that you said to me that

no one, not even Bannister, could have told that the papers were in your room, the case

began to take a definite shape in my mind. The printer one could, of course, dismiss. He

could examine the papers in his own office. The Indian I also thought nothing of. If the

proofs were in a roll, he could not possibly know what they were. On the other hand, it

seemed an unthinkable coincidence that a man should dare to enter the room, and that by

chance on that very day the papers were on the table. I dismissed that. The man who

entered knew that the papers were there. How did he know? “From the moment, Mr. Soames, that you said to me that

no one, not even Bannister, could have told that the papers were in your room, the case

began to take a definite shape in my mind. The printer one could, of course, dismiss. He

could examine the papers in his own office. The Indian I also thought nothing of. If the

proofs were in a roll, he could not possibly know what they were. On the other hand, it

seemed an unthinkable coincidence that a man should dare to enter the room, and that by

chance on that very day the papers were on the table. I dismissed that. The man who

entered knew that the papers were there. How did he know?

“When I approached your room, I examined the window. You

amused me by supposing that I was contemplating the possibility of someone having in broad

daylight, under the eyes of all these opposite rooms, forced himself through it. Such an

idea was absurd. I was measuring how tall a man would need to be in order to see, as he

passed, what papers were on the central table. I am six feet high, and I could do it with

an effort. No one less than that would have a chance. Already you see I had reason to

think that, if one of your three students was a man of unusual height, he was the most

worth watching of the three. “When I approached your room, I examined the window. You

amused me by supposing that I was contemplating the possibility of someone having in broad

daylight, under the eyes of all these opposite rooms, forced himself through it. Such an

idea was absurd. I was measuring how tall a man would need to be in order to see, as he

passed, what papers were on the central table. I am six feet high, and I could do it with

an effort. No one less than that would have a chance. Already you see I had reason to

think that, if one of your three students was a man of unusual height, he was the most

worth watching of the three.

“I entered, and I took you into my confidence as to the

suggestions of the side table. Of the centre table I could make nothing, until in your

description of [606] Gilchrist

you mentioned that he was a long-distance jumper. Then the whole thing came to me in an

instant, and I only needed certain corroborative proofs, which I speedily obtained. “I entered, and I took you into my confidence as to the

suggestions of the side table. Of the centre table I could make nothing, until in your

description of [606] Gilchrist

you mentioned that he was a long-distance jumper. Then the whole thing came to me in an

instant, and I only needed certain corroborative proofs, which I speedily obtained.

“What happened was this: This young fellow had employed

his afternoon at the athletic grounds, where he had been practising the jump. He returned

carrying his jumping-shoes, which are provided, as you are aware, with several sharp

spikes. As he passed your window he saw, by means of his great height, these proofs upon

your table, and conjectured what they were. No harm would have been done had it not been

that, as he passed your door, he perceived the key which had been left by the carelessness

of your servant. A sudden impulse came over him to enter, and see if they were indeed the

proofs. It was not a dangerous exploit, for he could always pretend that he had simply

looked in to ask a question. “What happened was this: This young fellow had employed

his afternoon at the athletic grounds, where he had been practising the jump. He returned

carrying his jumping-shoes, which are provided, as you are aware, with several sharp

spikes. As he passed your window he saw, by means of his great height, these proofs upon

your table, and conjectured what they were. No harm would have been done had it not been

that, as he passed your door, he perceived the key which had been left by the carelessness

of your servant. A sudden impulse came over him to enter, and see if they were indeed the

proofs. It was not a dangerous exploit, for he could always pretend that he had simply

looked in to ask a question.

“Well, when he saw that they were indeed the proofs, it

was then that he yielded to temptation. He put his shoes on the table. What was it you put

on that chair near the window?” “Well, when he saw that they were indeed the proofs, it

was then that he yielded to temptation. He put his shoes on the table. What was it you put

on that chair near the window?”

“Gloves,” said the young man. “Gloves,” said the young man.

Holmes looked triumphantly at Bannister. “He put his

gloves on the chair, and he took the proofs, sheet by sheet, to copy them. He thought the

tutor must return by the main gate, and that he would see him. As we know, he came back by

the side gate. Suddenly he heard him at the very door. There was no possible escape. He

forgot his gloves, but he caught up his shoes and darted into the bedroom. You observe

that the scratch on that table is slight at one side, but deepens in the direction of the

bedroom door. That in itself is enough to show us that the shoe had been drawn in that

direction, and that the culprit had taken refuge there. The earth round the spike had been

left on the table, and a second sample was loosened and fell in the bedroom. I may add

that I walked out to the athletic grounds this morning, saw that tenacious black clay is

used in the jumping-pit, and carried away a specimen of it, together with some of the fine

tan or sawdust which is strewn over it to prevent the athlete from slipping. Have I told

the truth, Mr. Gilchrist?” Holmes looked triumphantly at Bannister. “He put his

gloves on the chair, and he took the proofs, sheet by sheet, to copy them. He thought the

tutor must return by the main gate, and that he would see him. As we know, he came back by

the side gate. Suddenly he heard him at the very door. There was no possible escape. He

forgot his gloves, but he caught up his shoes and darted into the bedroom. You observe

that the scratch on that table is slight at one side, but deepens in the direction of the

bedroom door. That in itself is enough to show us that the shoe had been drawn in that

direction, and that the culprit had taken refuge there. The earth round the spike had been

left on the table, and a second sample was loosened and fell in the bedroom. I may add

that I walked out to the athletic grounds this morning, saw that tenacious black clay is

used in the jumping-pit, and carried away a specimen of it, together with some of the fine

tan or sawdust which is strewn over it to prevent the athlete from slipping. Have I told

the truth, Mr. Gilchrist?”

The student had drawn himself erect. The student had drawn himself erect.

“Yes, sir, it is true,” said he. “Yes, sir, it is true,” said he.

“Good heavens! have you nothing to add?” cried

Soames. “Good heavens! have you nothing to add?” cried

Soames.

“Yes, sir, I have, but the shock of this disgraceful

exposure has bewildered me. I have a letter here, Mr. Soames, which I wrote to you early

this morning in the middle of a restless night. It was before I knew that my sin had found

me out. Here it is, sir. You will see that I have said, ‘I have determined not to go

in for the examination. I have been offered a commission in the Rhodesian Police, and I am

going out to South Africa at once.’ ” “Yes, sir, I have, but the shock of this disgraceful

exposure has bewildered me. I have a letter here, Mr. Soames, which I wrote to you early

this morning in the middle of a restless night. It was before I knew that my sin had found

me out. Here it is, sir. You will see that I have said, ‘I have determined not to go

in for the examination. I have been offered a commission in the Rhodesian Police, and I am

going out to South Africa at once.’ ”

“I am indeed pleased to hear that you did not intend

to profit by your unfair advantage,” said Soames. “But why did you change your

purpose?” “I am indeed pleased to hear that you did not intend

to profit by your unfair advantage,” said Soames. “But why did you change your

purpose?”

Gilchrist pointed to Bannister. Gilchrist pointed to Bannister.

“There is the man who set me in the right path,”

said he. “There is the man who set me in the right path,”

said he.

“Come now, Bannister,” said Holmes. “It will be

clear to you, from what I have said, that only you could have let this young man out,

since you were left in the room, and must have locked the door when you went out. As to

his escaping by that window, it was incredible. Can you not clear up the last point in

this mystery, and tell us the reasons for your action?” “Come now, Bannister,” said Holmes. “It will be

clear to you, from what I have said, that only you could have let this young man out,

since you were left in the room, and must have locked the door when you went out. As to

his escaping by that window, it was incredible. Can you not clear up the last point in

this mystery, and tell us the reasons for your action?”

“It was simple enough, sir, if you only had known, but,

with all your cleverness, [607] it

was impossible that you could know. Time was, sir, when I was butler to old Sir Jabez

Gilchrist, this young gentleman’s father. When he was ruined I came to the college as

servant, but I never forgot my old employer because he was down in the world. I watched

his son all I could for the sake of the old days. Well, sir, when I came into this room

yesterday, when the alarm was given, the very first thing I saw was Mr. Gilchrist’s

tan gloves a-lying in that chair. I knew those gloves well, and I understood their

message. If Mr. Soames saw them, the game was up. I flopped down into that chair, and

nothing would budge me until Mr. Soames went for you. Then out came my poor young master,

whom I had dandled on my knee, and confessed it all to me. Wasn’t it natural, sir,

that I should save him, and wasn’t it natural also that I should try to speak to him

as his dead father would have done, and make him understand that he could not profit by

such a deed? Could you blame me, sir?” “It was simple enough, sir, if you only had known, but,

with all your cleverness, [607] it

was impossible that you could know. Time was, sir, when I was butler to old Sir Jabez

Gilchrist, this young gentleman’s father. When he was ruined I came to the college as

servant, but I never forgot my old employer because he was down in the world. I watched

his son all I could for the sake of the old days. Well, sir, when I came into this room

yesterday, when the alarm was given, the very first thing I saw was Mr. Gilchrist’s

tan gloves a-lying in that chair. I knew those gloves well, and I understood their

message. If Mr. Soames saw them, the game was up. I flopped down into that chair, and

nothing would budge me until Mr. Soames went for you. Then out came my poor young master,

whom I had dandled on my knee, and confessed it all to me. Wasn’t it natural, sir,

that I should save him, and wasn’t it natural also that I should try to speak to him

as his dead father would have done, and make him understand that he could not profit by

such a deed? Could you blame me, sir?”

“No, indeed,” said Holmes, heartily, springing to

his feet. “Well, Soames, I think we have cleared your little problem up, and our

breakfasts awaits us at home. Come, Watson! As to you, sir, I trust that a bright future

awaits you in Rhodesia. For once you have fallen low. Let us see, in the future, how high

you can rise.” “No, indeed,” said Holmes, heartily, springing to

his feet. “Well, Soames, I think we have cleared your little problem up, and our

breakfasts awaits us at home. Come, Watson! As to you, sir, I trust that a bright future

awaits you in Rhodesia. For once you have fallen low. Let us see, in the future, how high

you can rise.”

|

![]() We were residing at the time in furnished lodgings close to a

library where Sherlock Holmes was pursuing some laborious researches in early English

charters –researches which led to results so striking that they may be the subject of

one of my future narratives. Here it was that one evening we received a visit from an

acquaintance, Mr. Hilton Soames, tutor and lecturer at the College of St. Luke’s. Mr.

Soames was a tall, spare man, of a nervous and excitable temperament. I had always known

him to be restless in his manner, but on this particular occasion he was in such a state

of uncontrollable agitation that it was clear something very unusual had occurred.

We were residing at the time in furnished lodgings close to a

library where Sherlock Holmes was pursuing some laborious researches in early English

charters –researches which led to results so striking that they may be the subject of

one of my future narratives. Here it was that one evening we received a visit from an

acquaintance, Mr. Hilton Soames, tutor and lecturer at the College of St. Luke’s. Mr.

Soames was a tall, spare man, of a nervous and excitable temperament. I had always known

him to be restless in his manner, but on this particular occasion he was in such a state

of uncontrollable agitation that it was clear something very unusual had occurred.![]() “I trust, Mr. Holmes, that you can spare me a few hours

of your valuable time. We have had a very painful incident at St. Luke’s, and really,

but for the happy chance of your being in town, I should have been at a loss what to

do.”

“I trust, Mr. Holmes, that you can spare me a few hours

of your valuable time. We have had a very painful incident at St. Luke’s, and really,

but for the happy chance of your being in town, I should have been at a loss what to

do.”![]() “I am very busy just now, and I desire no

distractions,” my friend answered. “I should much prefer that you called in the

aid of the police.”

“I am very busy just now, and I desire no

distractions,” my friend answered. “I should much prefer that you called in the

aid of the police.”![]() “No, no, my dear sir; such a course is utterly

impossible. When once the law is evoked it cannot be stayed again, and this is just one of

those cases where, for the credit of the college, it is most essential to avoid scandal.

Your discretion is as well known as your powers, and you are the one man in the world who

can help me. I beg you, Mr. Holmes, to do what you can.”

“No, no, my dear sir; such a course is utterly

impossible. When once the law is evoked it cannot be stayed again, and this is just one of

those cases where, for the credit of the college, it is most essential to avoid scandal.

Your discretion is as well known as your powers, and you are the one man in the world who

can help me. I beg you, Mr. Holmes, to do what you can.”![]() My friend’s temper had not improved since he had been

deprived of the congenial surroundings of Baker Street. Without his scrapbooks, his

chemicals, and his homely untidiness, he was an uncomfortable man. He shrugged his

shoulders in ungracious acquiescence, while our visitor in hurried words and with much

excitable gesticulation poured forth his story.

My friend’s temper had not improved since he had been

deprived of the congenial surroundings of Baker Street. Without his scrapbooks, his

chemicals, and his homely untidiness, he was an uncomfortable man. He shrugged his

shoulders in ungracious acquiescence, while our visitor in hurried words and with much

excitable gesticulation poured forth his story.![]() “I must explain to you, Mr. Holmes, that to-morrow is the

first day of the examination for the Fortescue Scholarship. I am one of the examiners. My

subject is Greek, and the first of the papers consists of a large passage of Greek

translation which the candidate has not seen. This passage is printed on the examination

paper, and it would naturally be an immense advantage if the candidate could prepare it in

advance. For this reason, great care is taken to keep the paper secret.

“I must explain to you, Mr. Holmes, that to-morrow is the

first day of the examination for the Fortescue Scholarship. I am one of the examiners. My

subject is Greek, and the first of the papers consists of a large passage of Greek

translation which the candidate has not seen. This passage is printed on the examination

paper, and it would naturally be an immense advantage if the candidate could prepare it in

advance. For this reason, great care is taken to keep the paper secret.![]() [597] “To-day,

about three o’clock, the proofs of this paper arrived from the printers. The exercise

consists of half a chapter of Thucydides. I had to read it over carefully, as the text

must be absolutely correct. At four-thirty my task was not yet completed. I had, however,

promised to take tea in a friend’s rooms, so I left the proof upon my desk. I was

absent rather more than an hour.

[597] “To-day,

about three o’clock, the proofs of this paper arrived from the printers. The exercise

consists of half a chapter of Thucydides. I had to read it over carefully, as the text

must be absolutely correct. At four-thirty my task was not yet completed. I had, however,

promised to take tea in a friend’s rooms, so I left the proof upon my desk. I was

absent rather more than an hour.![]() “You are aware, Mr. Holmes, that our college doors are

double–a green baize one within and a heavy oak one without. As I approached my outer

door, I was amazed to see a key in it. For an instant I imagined that I had left my own

there, but on feeling in my pocket I found that it was all right. The only duplicate which

existed, so far as I knew, was that which belonged to my servant, Bannister–a man who

has looked after my room for ten years, and whose honesty is absolutely above suspicion. I

found that the key was indeed his, that he had entered my room to know if I wanted tea,

and that he had very carelessly left the key in the door when he came out. His visit to my

room must have been within a very few minutes of my leaving it. His forgetfulness about

the key would have mattered little upon any other occasion, but on this one day it has

produced the most deplorable consequences.

“You are aware, Mr. Holmes, that our college doors are

double–a green baize one within and a heavy oak one without. As I approached my outer

door, I was amazed to see a key in it. For an instant I imagined that I had left my own

there, but on feeling in my pocket I found that it was all right. The only duplicate which

existed, so far as I knew, was that which belonged to my servant, Bannister–a man who

has looked after my room for ten years, and whose honesty is absolutely above suspicion. I

found that the key was indeed his, that he had entered my room to know if I wanted tea,

and that he had very carelessly left the key in the door when he came out. His visit to my

room must have been within a very few minutes of my leaving it. His forgetfulness about

the key would have mattered little upon any other occasion, but on this one day it has

produced the most deplorable consequences.![]() “The moment I looked at my table, I was aware that

someone had rummaged among my papers. The proof was in three long slips. I had left them

all together. Now, I found that one of them was lying on the floor, one was on the side

table near the window, and the third was where I had left it.”

“The moment I looked at my table, I was aware that

someone had rummaged among my papers. The proof was in three long slips. I had left them

all together. Now, I found that one of them was lying on the floor, one was on the side

table near the window, and the third was where I had left it.”![]() Holmes stirred for the first time.

Holmes stirred for the first time.![]() “The first page on the floor, the second in the window,

the third where you left it,” said he.

“The first page on the floor, the second in the window,

the third where you left it,” said he.