|

|

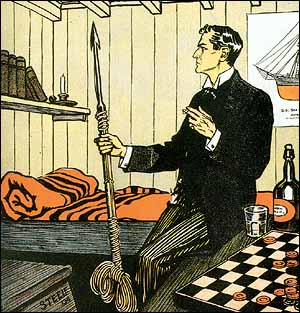

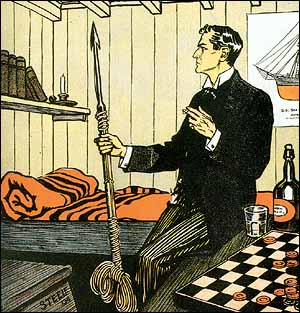

“If you could have looked into Allardyce’s back

shop, you would have seen a dead pig swung from a hook in the ceiling, and a gentleman in

his shirt sleeves furiously stabbing at it with this weapon. I was that energetic person,

and I have satisfied myself that by no exertion of my strength can I transfix the pig with

a single blow. Perhaps you would care to try?” “If you could have looked into Allardyce’s back

shop, you would have seen a dead pig swung from a hook in the ceiling, and a gentleman in

his shirt sleeves furiously stabbing at it with this weapon. I was that energetic person,

and I have satisfied myself that by no exertion of my strength can I transfix the pig with

a single blow. Perhaps you would care to try?”

“Not for worlds. But why were you doing this?” “Not for worlds. But why were you doing this?”

“Because it seemed to me to have an indirect bearing upon

the mystery of Woodman’s Lee. Ah, Hopkins, I got your wire last night, and I have

been expecting you. Come and join us.” “Because it seemed to me to have an indirect bearing upon

the mystery of Woodman’s Lee. Ah, Hopkins, I got your wire last night, and I have

been expecting you. Come and join us.”

Our visitor was an exceedingly alert man, thirty years of age,

dressed in a quiet tweed suit, but retaining the erect bearing of one who was accustomed

to official [560] uniform. I

recognized him at once as Stanley Hopkins, a young police inspector, for whose future

Holmes had high hopes, while he in turn professed the admiration and respect of a pupil

for the scientific methods of the famous amateur. Hopkins’s brow was clouded, and he

sat down with an air of deep dejection. Our visitor was an exceedingly alert man, thirty years of age,

dressed in a quiet tweed suit, but retaining the erect bearing of one who was accustomed

to official [560] uniform. I

recognized him at once as Stanley Hopkins, a young police inspector, for whose future

Holmes had high hopes, while he in turn professed the admiration and respect of a pupil

for the scientific methods of the famous amateur. Hopkins’s brow was clouded, and he

sat down with an air of deep dejection.

“No, thank you, sir. I breakfasted before I came round. I

spent the night in town, for I came up yesterday to report.” “No, thank you, sir. I breakfasted before I came round. I

spent the night in town, for I came up yesterday to report.”

“And what had you to report?” “And what had you to report?”

“Failure, sir, absolute failure.” “Failure, sir, absolute failure.”

“You have made no progress?” “You have made no progress?”

“None.” “None.”

“Dear me! I must have a look at the matter.” “Dear me! I must have a look at the matter.”

“I wish to heavens that you would, Mr. Holmes. It’s

my first big chance, and I am at my wit’s end. For goodness’ sake, come down and

lend me a hand.” “I wish to heavens that you would, Mr. Holmes. It’s

my first big chance, and I am at my wit’s end. For goodness’ sake, come down and

lend me a hand.”

“Well, well, it just happens that I have already read all

the available evidence, including the report of the inquest, with some care. By the way,

what do you make of that tobacco pouch, found on the scene of the crime? Is there no clue

there?” “Well, well, it just happens that I have already read all

the available evidence, including the report of the inquest, with some care. By the way,

what do you make of that tobacco pouch, found on the scene of the crime? Is there no clue

there?”

Hopkins looked surprised. Hopkins looked surprised.

“It was the man’s own pouch, sir. His initials were

inside it. And it was of sealskin–and he was an old sealer.” “It was the man’s own pouch, sir. His initials were

inside it. And it was of sealskin–and he was an old sealer.”

“But he had no pipe.” “But he had no pipe.”

“No, sir, we could find no pipe. Indeed, he smoked very

little, and yet he might have kept some tobacco for his friends.” “No, sir, we could find no pipe. Indeed, he smoked very

little, and yet he might have kept some tobacco for his friends.”

“No doubt. I only mention it because, if I had been

handling the case, I should have been inclined to make that the starting-point of my

investigation. However, my friend, Dr. Watson, knows nothing of this matter, and I should

be none the worse for hearing the sequence of events once more. Just give us some short

sketches of the essentials.” “No doubt. I only mention it because, if I had been

handling the case, I should have been inclined to make that the starting-point of my

investigation. However, my friend, Dr. Watson, knows nothing of this matter, and I should

be none the worse for hearing the sequence of events once more. Just give us some short

sketches of the essentials.”

Stanley Hopkins drew a slip of paper from his pocket. Stanley Hopkins drew a slip of paper from his pocket.

“I have a few dates here which will give you the career

of the dead man, Captain Peter Carey. He was born in ’45–fifty years of age. He

was a most daring and successful seal and whale fisher. In 1883 he commanded the steam

sealer Sea Unicorn, of Dundee. He had then had several successful voyages in succession,

and in the following year, 1884, he retired. After that he travelled for some years, and

finally he bought a small place called Woodman’s Lee, near Forest Row, in Sussex.

There he has lived for six years, and there he died just a week ago to-day. “I have a few dates here which will give you the career

of the dead man, Captain Peter Carey. He was born in ’45–fifty years of age. He

was a most daring and successful seal and whale fisher. In 1883 he commanded the steam

sealer Sea Unicorn, of Dundee. He had then had several successful voyages in succession,

and in the following year, 1884, he retired. After that he travelled for some years, and

finally he bought a small place called Woodman’s Lee, near Forest Row, in Sussex.

There he has lived for six years, and there he died just a week ago to-day.

“There were some most singular points about the man. In

ordinary life, he was a strict Puritan–a silent, gloomy fellow. His household

consisted of his wife, his daughter, aged twenty, and two female servants. These last were

continually changing, for it was never a very cheery situation, and sometimes it became

past all bearing. The man was an intermittent drunkard, and when he had the fit on him he

was a perfect fiend. He has been known to drive his wife and daughter out of doors in the

middle of the night and flog them through the park until the whole village outside the

gates was aroused by their screams. “There were some most singular points about the man. In

ordinary life, he was a strict Puritan–a silent, gloomy fellow. His household

consisted of his wife, his daughter, aged twenty, and two female servants. These last were

continually changing, for it was never a very cheery situation, and sometimes it became

past all bearing. The man was an intermittent drunkard, and when he had the fit on him he

was a perfect fiend. He has been known to drive his wife and daughter out of doors in the

middle of the night and flog them through the park until the whole village outside the

gates was aroused by their screams.

“He was summoned once for a savage assault upon the old

vicar, who had called upon him to remonstrate with him upon his conduct. In short, Mr.

Holmes, you would go far before you found a more dangerous man than Peter Carey, and I

have heard that he bore the same character when he commanded his ship. He was known in the

trade as Black Peter, and the name was given him, not only on [561] account of his swarthy features and the colour of his

huge beard, but for the humours which were the terror of all around him. I need not say

that he was loathed and avoided by every one of his neighbours, and that I have not heard

one single word of sorrow about his terrible end. “He was summoned once for a savage assault upon the old

vicar, who had called upon him to remonstrate with him upon his conduct. In short, Mr.

Holmes, you would go far before you found a more dangerous man than Peter Carey, and I

have heard that he bore the same character when he commanded his ship. He was known in the

trade as Black Peter, and the name was given him, not only on [561] account of his swarthy features and the colour of his

huge beard, but for the humours which were the terror of all around him. I need not say

that he was loathed and avoided by every one of his neighbours, and that I have not heard

one single word of sorrow about his terrible end.

“You must have read in the account of the inquest about

the man’s cabin, Mr. Holmes, but perhaps your friend here has not heard of it. He had

built himself a wooden outhouse–he always called it the ‘cabin’–a few

hundred yards from his house, and it was here that he slept every night. It was a little,

single-roomed hut, sixteen feet by ten. He kept the key in his pocket, made his own bed,

cleaned it himself, and allowed no other foot to cross the threshold. There are small

windows on each side, which were covered by curtains and never opened. One of these

windows was turned towards the high road, and when the light burned in it at night the

folk used to point it out to each other and wonder what Black Peter was doing in there.

That’s the window, Mr. Holmes, which gave us one of the few bits of positive evidence

that came out at the inquest. “You must have read in the account of the inquest about

the man’s cabin, Mr. Holmes, but perhaps your friend here has not heard of it. He had

built himself a wooden outhouse–he always called it the ‘cabin’–a few

hundred yards from his house, and it was here that he slept every night. It was a little,

single-roomed hut, sixteen feet by ten. He kept the key in his pocket, made his own bed,

cleaned it himself, and allowed no other foot to cross the threshold. There are small

windows on each side, which were covered by curtains and never opened. One of these

windows was turned towards the high road, and when the light burned in it at night the

folk used to point it out to each other and wonder what Black Peter was doing in there.

That’s the window, Mr. Holmes, which gave us one of the few bits of positive evidence

that came out at the inquest.

“You remember that a stonemason, named Slater, walking

from Forest Row about one o’clock in the morning–two days before the

murder–stopped as he passed the grounds and looked at the square of light still

shining among the trees. He swears that the shadow of a man’s head turned sideways

was clearly visible on the blind, and that this shadow was certainly not that of Peter

Carey, whom he knew well. It was that of a bearded man, but the beard was short and

bristled forward in a way very different from that of the captain. So he says, but he had

been two hours in the public-house, and it is some distance from the road to the window.

Besides, this refers to the Monday, and the crime was done upon the Wednesday. “You remember that a stonemason, named Slater, walking

from Forest Row about one o’clock in the morning–two days before the

murder–stopped as he passed the grounds and looked at the square of light still

shining among the trees. He swears that the shadow of a man’s head turned sideways

was clearly visible on the blind, and that this shadow was certainly not that of Peter

Carey, whom he knew well. It was that of a bearded man, but the beard was short and

bristled forward in a way very different from that of the captain. So he says, but he had

been two hours in the public-house, and it is some distance from the road to the window.

Besides, this refers to the Monday, and the crime was done upon the Wednesday.

“On the Tuesday, Peter Carey was in one of his blackest

moods, flushed with drink and as savage as a dangerous wild beast. He roamed about the

house, and the women ran for it when they heard him coming. Late in the evening, he went

down to his own hut. About two o’clock the following morning, his daughter, who slept

with her window open, heard a most fearful yell from that direction, but it was no unusual

thing for him to bawl and shout when he was in drink, so no notice was taken. On rising at

seven, one of the maids noticed that the door of the hut was open, but so great was the

terror which the man caused that it was midday before anyone would venture down to see

what had become of him. Peeping into the open door, they saw a sight which sent them

flying, with white faces, into the village. Within an hour, I was on the spot and had

taken over the case. “On the Tuesday, Peter Carey was in one of his blackest

moods, flushed with drink and as savage as a dangerous wild beast. He roamed about the

house, and the women ran for it when they heard him coming. Late in the evening, he went

down to his own hut. About two o’clock the following morning, his daughter, who slept

with her window open, heard a most fearful yell from that direction, but it was no unusual

thing for him to bawl and shout when he was in drink, so no notice was taken. On rising at

seven, one of the maids noticed that the door of the hut was open, but so great was the

terror which the man caused that it was midday before anyone would venture down to see

what had become of him. Peeping into the open door, they saw a sight which sent them

flying, with white faces, into the village. Within an hour, I was on the spot and had

taken over the case.

“Well, I have fairly steady nerves, as you know, Mr.

Holmes, but I give you my word, that I got a shake when I put my head into that little

house. It was droning like a harmonium with the flies and bluebottles, and the floor and

walls were like a slaughter-house. He had called it a cabin, and a cabin it was, sure

enough, for you would have thought that you were in a ship. There was a bunk at one end, a

sea-chest, maps and charts, a picture of the Sea Unicorn, a line of logbooks on a

shelf, all exactly as one would expect to find it in a captain’s room. And there, in

the middle of it, was the man himself–his face twisted like a lost soul in torment,

and his great brindled beard stuck upward in his agony. Right through his broad breast a

steel harpoon had been driven, and it had sunk deep into the wood of the wall behind him.

He was pinned like a beetle on a card. Of course, he was quite dead, and had been so from

the instant that he had uttered that last yell of agony. “Well, I have fairly steady nerves, as you know, Mr.

Holmes, but I give you my word, that I got a shake when I put my head into that little

house. It was droning like a harmonium with the flies and bluebottles, and the floor and

walls were like a slaughter-house. He had called it a cabin, and a cabin it was, sure

enough, for you would have thought that you were in a ship. There was a bunk at one end, a

sea-chest, maps and charts, a picture of the Sea Unicorn, a line of logbooks on a

shelf, all exactly as one would expect to find it in a captain’s room. And there, in

the middle of it, was the man himself–his face twisted like a lost soul in torment,

and his great brindled beard stuck upward in his agony. Right through his broad breast a

steel harpoon had been driven, and it had sunk deep into the wood of the wall behind him.

He was pinned like a beetle on a card. Of course, he was quite dead, and had been so from

the instant that he had uttered that last yell of agony.

[562] “I

know your methods, sir, and I applied them. Before I permitted anything to be moved, I

examined most carefully the ground outside, and also the floor of the room. There were no

footmarks.” [562] “I

know your methods, sir, and I applied them. Before I permitted anything to be moved, I

examined most carefully the ground outside, and also the floor of the room. There were no

footmarks.”

“Meaning that you saw none?” “Meaning that you saw none?”

“I assure you, sir, that there were none.” “I assure you, sir, that there were none.”

“My good Hopkins, I have investigated many crimes, but I

have never yet seen one which was committed by a flying creature. As long as the criminal

remains upon two legs so long must there be some indentation, some abrasion, some trifling

displacement which can be detected by the scientific searcher. It is incredible that this

blood-bespattered room contained no trace which could have aided us. I understand,

however, from the inquest that there were some objects which you failed to overlook?” “My good Hopkins, I have investigated many crimes, but I

have never yet seen one which was committed by a flying creature. As long as the criminal

remains upon two legs so long must there be some indentation, some abrasion, some trifling

displacement which can be detected by the scientific searcher. It is incredible that this

blood-bespattered room contained no trace which could have aided us. I understand,

however, from the inquest that there were some objects which you failed to overlook?”

The young inspector winced at my companion’s ironical

comments. The young inspector winced at my companion’s ironical

comments.

“I was a fool not to call you in at the time, Mr. Holmes.

However, that’s past praying for now. Yes, there were several objects in the room

which called for special attention. One was the harpoon with which the deed was committed.

It had been snatched down from a rack on the wall. Two others remained there, and there

was a vacant place for the third. On the stock was engraved ‘SS. Sea Unicorn,

Dundee.’ This seemed to establish that the crime had been done in a moment of fury,

and that the murderer had seized the first weapon which came in his way. The fact that the

crime was committed at two in the morning, and yet Peter Carey was fully dressed,

suggested that he had an appointment with the murderer, which is borne out by the fact

that a bottle of rum and two dirty glasses stood upon the table.” “I was a fool not to call you in at the time, Mr. Holmes.

However, that’s past praying for now. Yes, there were several objects in the room

which called for special attention. One was the harpoon with which the deed was committed.

It had been snatched down from a rack on the wall. Two others remained there, and there

was a vacant place for the third. On the stock was engraved ‘SS. Sea Unicorn,

Dundee.’ This seemed to establish that the crime had been done in a moment of fury,

and that the murderer had seized the first weapon which came in his way. The fact that the

crime was committed at two in the morning, and yet Peter Carey was fully dressed,

suggested that he had an appointment with the murderer, which is borne out by the fact

that a bottle of rum and two dirty glasses stood upon the table.”

“Yes,” said Holmes; “I think that both

inferences are permissible. Was there any other spirit but rum in the room?” “Yes,” said Holmes; “I think that both

inferences are permissible. Was there any other spirit but rum in the room?”

“Yes, there was a tantalus containing brandy and whisky

on the sea-chest. It is of no importance to us, however, since the decanters were full,

and it had therefore not been used.” “Yes, there was a tantalus containing brandy and whisky

on the sea-chest. It is of no importance to us, however, since the decanters were full,

and it had therefore not been used.”

“For all that, its presence has some significance,”

said Holmes. “However, let us hear some more about the objects which do seem to you

to bear upon the case.” “For all that, its presence has some significance,”

said Holmes. “However, let us hear some more about the objects which do seem to you

to bear upon the case.”

“There was this tobacco-pouch upon the table.” “There was this tobacco-pouch upon the table.”

“What part of the table?” “What part of the table?”

“It lay in the middle. It was of coarse sealskin–the

straight-haired skin, with a leather thong to bind it. Inside was ‘P. C.’ on the

flap. There was half an ounce of strong ship’s tobacco in it.” “It lay in the middle. It was of coarse sealskin–the

straight-haired skin, with a leather thong to bind it. Inside was ‘P. C.’ on the

flap. There was half an ounce of strong ship’s tobacco in it.”

“Excellent! What more?” “Excellent! What more?”

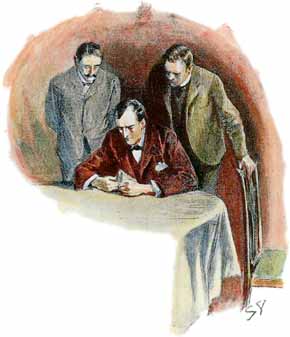

Stanley Hopkins drew from his pocket a drab-covered notebook.

The outside was rough and worn, the leaves discoloured. On the first page were written the

initials “J. H. N.” and the date “1883.” Holmes laid it on the table

and examined it in his minute way, while Hopkins and I gazed over each shoulder. On the

second page were the printed letters “C. P. R.,” and then came several sheets of

numbers. Another heading was “Argentine,” another “Costa Rica,” and

another “San Paulo,” each with pages of signs and figures after it. Stanley Hopkins drew from his pocket a drab-covered notebook.

The outside was rough and worn, the leaves discoloured. On the first page were written the

initials “J. H. N.” and the date “1883.” Holmes laid it on the table

and examined it in his minute way, while Hopkins and I gazed over each shoulder. On the

second page were the printed letters “C. P. R.,” and then came several sheets of

numbers. Another heading was “Argentine,” another “Costa Rica,” and

another “San Paulo,” each with pages of signs and figures after it.

“What do you make of these?” asked Holmes. “What do you make of these?” asked Holmes.

“They appear to be lists of Stock Exchange securities. I

thought that ‘J. H. N.’ were the initials of a broker, and that ‘C. P.

R.’ may have been his client.” “They appear to be lists of Stock Exchange securities. I

thought that ‘J. H. N.’ were the initials of a broker, and that ‘C. P.

R.’ may have been his client.”

“Try Canadian Pacific Railway,” said Holmes. “Try Canadian Pacific Railway,” said Holmes.

Stanley Hopkins swore between his teeth, and struck his thigh

with his clenched hand. Stanley Hopkins swore between his teeth, and struck his thigh

with his clenched hand.

[563] “What

a fool I have been!” he cried. “Of course, it is as you say. Then ‘J. H.

N.’ are the only initials we have to solve. I have already examined the old Stock

Exchange lists, and I can find no one in 1883, either in the house or among the outside

brokers, whose initials correspond with these. Yet I feel that the clue is the most

important one that I hold. You will admit, Mr. Holmes, that there is a possibility that

these initials are those of the second person who was present–in other words, of the

murderer. I would also urge that the introduction into the case of a document relating to

large masses of valuable securities gives us for the first time some indication of a

motive for the crime.” [563] “What

a fool I have been!” he cried. “Of course, it is as you say. Then ‘J. H.

N.’ are the only initials we have to solve. I have already examined the old Stock

Exchange lists, and I can find no one in 1883, either in the house or among the outside

brokers, whose initials correspond with these. Yet I feel that the clue is the most

important one that I hold. You will admit, Mr. Holmes, that there is a possibility that

these initials are those of the second person who was present–in other words, of the

murderer. I would also urge that the introduction into the case of a document relating to

large masses of valuable securities gives us for the first time some indication of a

motive for the crime.”

Sherlock Holmes’s face showed that he was thoroughly

taken aback by this new development. Sherlock Holmes’s face showed that he was thoroughly

taken aback by this new development.

“I must admit both your points,” said he. “I

confess that this notebook, which did not appear at the inquest, modifies any views which

I may have formed. I had come to a theory of the crime in which I can find no place for

this. Have you endeavoured to trace any of the securities here mentioned?” “I must admit both your points,” said he. “I

confess that this notebook, which did not appear at the inquest, modifies any views which

I may have formed. I had come to a theory of the crime in which I can find no place for

this. Have you endeavoured to trace any of the securities here mentioned?”

“Inquiries are now being made at the offices, but I fear

that the complete register of the stockholders of these South American concerns is in

South America, and that some weeks must elapse before we can trace the shares.” “Inquiries are now being made at the offices, but I fear

that the complete register of the stockholders of these South American concerns is in

South America, and that some weeks must elapse before we can trace the shares.”

Holmes had been examining the cover of the notebook with his

magnifying lens. Holmes had been examining the cover of the notebook with his

magnifying lens.

“Surely there is some discolouration here,” said he. “Surely there is some discolouration here,” said he.

“Yes, sir, it is a blood-stain. I told you that I picked

the book off the floor.” “Yes, sir, it is a blood-stain. I told you that I picked

the book off the floor.”

“Was the blood-stain above or below?” “Was the blood-stain above or below?”

“On the side next the boards.” “On the side next the boards.”

“Which proves, of course, that the book was dropped after

the crime was committed.” “Which proves, of course, that the book was dropped after

the crime was committed.”

“Exactly, Mr. Holmes. I appreciated that point, and I

conjectured that it was dropped by the murderer in his hurried flight. It lay near the

door.” “Exactly, Mr. Holmes. I appreciated that point, and I

conjectured that it was dropped by the murderer in his hurried flight. It lay near the

door.”

“I suppose that none of these securities have been found

among the property of the dead man?” “I suppose that none of these securities have been found

among the property of the dead man?”

“No, sir.” “No, sir.”

“Have you any reason to suspect robbery?” “Have you any reason to suspect robbery?”

“No, sir. Nothing seemed to have been touched.” “No, sir. Nothing seemed to have been touched.”

“Dear me, it is certainly a very interesting case. Then

there was a knife, was there not?” “Dear me, it is certainly a very interesting case. Then

there was a knife, was there not?”

“A sheath-knife, still in its sheath. It lay at the feet

of the dead man. Mrs. Carey has identified it as being her husband’s property.” “A sheath-knife, still in its sheath. It lay at the feet

of the dead man. Mrs. Carey has identified it as being her husband’s property.”

Holmes was lost in thought for some time. Holmes was lost in thought for some time.

“Well,” said he, at last, “I suppose I shall

have to come out and have a look at it.” “Well,” said he, at last, “I suppose I shall

have to come out and have a look at it.”

Stanley Hopkins gave a cry of joy. Stanley Hopkins gave a cry of joy.

“Thank you, sir. That will, indeed, be a weight off my

mind.” “Thank you, sir. That will, indeed, be a weight off my

mind.”

Holmes shook his finger at the inspector. Holmes shook his finger at the inspector.

“It would have been an easier task a week ago,” said

he. “But even now my visit may not be entirely fruitless. Watson, if you can spare

the time, I should be very glad of your company. If you will call a four-wheeler, Hopkins,

we shall be ready to start for Forest Row in a quarter of an hour.” “It would have been an easier task a week ago,” said

he. “But even now my visit may not be entirely fruitless. Watson, if you can spare

the time, I should be very glad of your company. If you will call a four-wheeler, Hopkins,

we shall be ready to start for Forest Row in a quarter of an hour.”

Alighting at the small wayside station, we drove for some

miles through the remains of widespread woods, which were once part of that great forest

which for [564] so long held

the Saxon invaders at bay–the impenetrable “weald,” for sixty years the

bulwark of Britain. Vast sections of it have been cleared, for this is the seat of the

first iron-works of the country, and the trees have been felled to smelt the ore. Now the

richer fields of the North have absorbed the trade, and nothing save these ravaged groves

and great scars in the earth show the work of the past. Here, in a clearing upon the green

slope of a hill, stood a long, low, stone house, approached by a curving drive running

through the fields. Nearer the road, and surrounded on three sides by bushes, was a small

outhouse, one window and the door facing in our direction. It was the scene of the murder. Alighting at the small wayside station, we drove for some

miles through the remains of widespread woods, which were once part of that great forest

which for [564] so long held

the Saxon invaders at bay–the impenetrable “weald,” for sixty years the

bulwark of Britain. Vast sections of it have been cleared, for this is the seat of the

first iron-works of the country, and the trees have been felled to smelt the ore. Now the

richer fields of the North have absorbed the trade, and nothing save these ravaged groves

and great scars in the earth show the work of the past. Here, in a clearing upon the green

slope of a hill, stood a long, low, stone house, approached by a curving drive running

through the fields. Nearer the road, and surrounded on three sides by bushes, was a small

outhouse, one window and the door facing in our direction. It was the scene of the murder.

Stanley Hopkins led us first to the house, where he introduced

us to a haggard, gray-haired woman, the widow of the murdered man, whose gaunt and

deep-lined face, with the furtive look of terror in the depths of her red-rimmed eyes,

told of the years of hardship and ill-usage which she had endured. With her was her

daughter, a pale, fair-haired girl, whose eyes blazed defiantly at us as she told us that

she was glad that her father was dead, and that she blessed the hand which had struck him

down. It was a terrible household that Black Peter Carey had made for himself, and it was

with a sense of relief that we found ourselves in the sunlight again and making our way

along a path which had been worn across the fields by the feet of the dead man. Stanley Hopkins led us first to the house, where he introduced

us to a haggard, gray-haired woman, the widow of the murdered man, whose gaunt and

deep-lined face, with the furtive look of terror in the depths of her red-rimmed eyes,

told of the years of hardship and ill-usage which she had endured. With her was her

daughter, a pale, fair-haired girl, whose eyes blazed defiantly at us as she told us that

she was glad that her father was dead, and that she blessed the hand which had struck him

down. It was a terrible household that Black Peter Carey had made for himself, and it was

with a sense of relief that we found ourselves in the sunlight again and making our way

along a path which had been worn across the fields by the feet of the dead man.

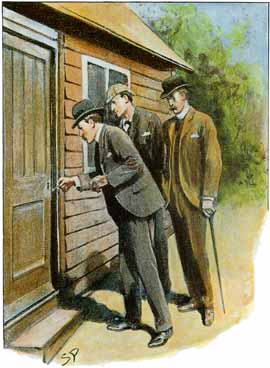

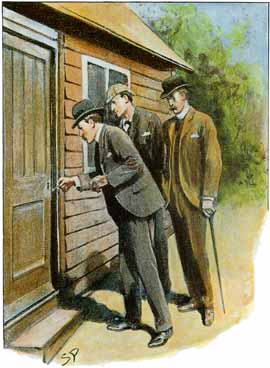

The outhouse was the simplest of dwellings, wooden-walled,

shingle-roofed, one window beside the door and one on the farther side. Stanley Hopkins

drew the key from his pocket and had stooped to the lock, when he paused with a look of

attention and surprise upon his face. The outhouse was the simplest of dwellings, wooden-walled,

shingle-roofed, one window beside the door and one on the farther side. Stanley Hopkins

drew the key from his pocket and had stooped to the lock, when he paused with a look of

attention and surprise upon his face.

“Someone has been tampering with it,” he said. “Someone has been tampering with it,” he said.

There could be no doubt of the fact. The woodwork was cut, and

the scratches showed white through the paint, as if they had been that instant done.

Holmes had been examining the window. There could be no doubt of the fact. The woodwork was cut, and

the scratches showed white through the paint, as if they had been that instant done.

Holmes had been examining the window.

“Someone has tried to force this also. Whoever it was has

failed to make his way in. He must have been a very poor burglar.” “Someone has tried to force this also. Whoever it was has

failed to make his way in. He must have been a very poor burglar.”

“This is a most extraordinary thing,” said the

inspector, “I could swear that these marks were not here yesterday evening.” “This is a most extraordinary thing,” said the

inspector, “I could swear that these marks were not here yesterday evening.”

“Some curious person from the village, perhaps,” I

suggested. “Some curious person from the village, perhaps,” I

suggested.

“Very unlikely. Few of them would dare to set foot in the

grounds, far less try to force their way into the cabin. What do you think of it, Mr.

Holmes?” “Very unlikely. Few of them would dare to set foot in the

grounds, far less try to force their way into the cabin. What do you think of it, Mr.

Holmes?”

“I think that fortune is very kind to us.” “I think that fortune is very kind to us.”

“You mean that the person will come again?” “You mean that the person will come again?”

“It is very probable. He came expecting to find the door

open. He tried to get in with the blade of a very small penknife. He could not manage it.

What would he do?” “It is very probable. He came expecting to find the door

open. He tried to get in with the blade of a very small penknife. He could not manage it.

What would he do?”

“Come again next night with a more useful tool.” “Come again next night with a more useful tool.”

“So I should say. It will be our fault if we are not

there to receive him. Meanwhile, let me see the inside of the cabin.” “So I should say. It will be our fault if we are not

there to receive him. Meanwhile, let me see the inside of the cabin.”

The traces of the tragedy had been removed, but the furniture

within the little room still stood as it had been on the night of the crime. For two

hours, with most intense concentration, Holmes examined every object in turn, but his face

showed that his quest was not a successful one. Once only he paused in his patient

investigation. The traces of the tragedy had been removed, but the furniture

within the little room still stood as it had been on the night of the crime. For two

hours, with most intense concentration, Holmes examined every object in turn, but his face

showed that his quest was not a successful one. Once only he paused in his patient

investigation.

“Have you taken anything off this shelf,

Hopkins?” “Have you taken anything off this shelf,

Hopkins?”

“No, I have moved nothing.” “No, I have moved nothing.”

[565] “Something

has been taken. There is less dust in this corner of the shelf than elsewhere. It may have

been a book lying on its side. It may have been a box. Well, well, I can do nothing more.

Let us walk in these beautiful woods, Watson, and give a few hours to the birds and the

flowers. We shall meet you here later, Hopkins, and see if we can come to closer quarters

with the gentleman who has paid this visit in the night.” [565] “Something

has been taken. There is less dust in this corner of the shelf than elsewhere. It may have

been a book lying on its side. It may have been a box. Well, well, I can do nothing more.

Let us walk in these beautiful woods, Watson, and give a few hours to the birds and the

flowers. We shall meet you here later, Hopkins, and see if we can come to closer quarters

with the gentleman who has paid this visit in the night.”

It was past eleven o’clock when we formed our little

ambuscade. Hopkins was for leaving the door of the hut open, but Holmes was of the opinion

that this would rouse the suspicions of the stranger. The lock was a perfectly simple one,

and only a strong blade was needed to push it back. Holmes also suggested that we should

wait, not inside the hut, but outside it, among the bushes which grew round the farther

window. In this way we should be able to watch our man if he struck a light, and see what

his object was in this stealthy nocturnal visit. It was past eleven o’clock when we formed our little

ambuscade. Hopkins was for leaving the door of the hut open, but Holmes was of the opinion

that this would rouse the suspicions of the stranger. The lock was a perfectly simple one,

and only a strong blade was needed to push it back. Holmes also suggested that we should

wait, not inside the hut, but outside it, among the bushes which grew round the farther

window. In this way we should be able to watch our man if he struck a light, and see what

his object was in this stealthy nocturnal visit.

It was a long and melancholy vigil, and yet brought with it

something of the thrill which the hunter feels when he lies beside the water-pool, and

waits for the coming of the thirsty beast of prey. What savage creature was it which might

steal upon us out of the darkness? Was it a fierce tiger of crime, which could only be

taken fighting hard with flashing fang and claw, or would it prove to be some skulking

jackal, dangerous only to the weak and unguarded? It was a long and melancholy vigil, and yet brought with it

something of the thrill which the hunter feels when he lies beside the water-pool, and

waits for the coming of the thirsty beast of prey. What savage creature was it which might

steal upon us out of the darkness? Was it a fierce tiger of crime, which could only be

taken fighting hard with flashing fang and claw, or would it prove to be some skulking

jackal, dangerous only to the weak and unguarded?

In absolute silence we crouched amongst the bushes, waiting

for whatever might come. At first the steps of a few belated villagers, or the sound of

voices from the village, lightened our vigil, but one by one these interruptions died

away, and an absolute stillness fell upon us, save for the chimes of the distant church,

which told us of the progress of the night, and for the rustle and whisper of a fine rain

falling amid the foliage which roofed us in. In absolute silence we crouched amongst the bushes, waiting

for whatever might come. At first the steps of a few belated villagers, or the sound of

voices from the village, lightened our vigil, but one by one these interruptions died

away, and an absolute stillness fell upon us, save for the chimes of the distant church,

which told us of the progress of the night, and for the rustle and whisper of a fine rain

falling amid the foliage which roofed us in.

Half-past two had chimed, and it was the darkest hour which

precedes the dawn, when we all started as a low but sharp click came from the direction of

the gate. Someone had entered the drive. Again there was a long silence, and I had begun

to fear that it was a false alarm, when a stealthy step was heard upon the other side of

the hut, and a moment later a metallic scraping and clinking. The man was trying to force

the lock. This time his skill was greater or his tool was better, for there was a sudden

snap and the creak of the hinges. Then a match was struck, and next instant the steady

light from a candle filled the interior of the hut. Through the gauze curtain our eyes

were all riveted upon the scene within. Half-past two had chimed, and it was the darkest hour which

precedes the dawn, when we all started as a low but sharp click came from the direction of

the gate. Someone had entered the drive. Again there was a long silence, and I had begun

to fear that it was a false alarm, when a stealthy step was heard upon the other side of

the hut, and a moment later a metallic scraping and clinking. The man was trying to force

the lock. This time his skill was greater or his tool was better, for there was a sudden

snap and the creak of the hinges. Then a match was struck, and next instant the steady

light from a candle filled the interior of the hut. Through the gauze curtain our eyes

were all riveted upon the scene within.

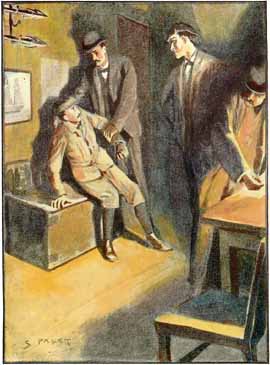

The nocturnal visitor was a young man, frail and thin, with

a black moustache, which intensified the deadly pallor of his face. He could not have been

much above twenty years of age. I have never seen any human being who appeared to be in

such a pitiable fright, for his teeth were visibly chattering, and he was shaking in every

limb. He was dressed like a gentleman, in Norfolk jacket and knickerbockers, with a cloth

cap upon his head. We watched him staring round with frightened eyes. Then he laid the

candle-end upon the table and disappeared from our view into one of the corners. He

returned with a large book, one of the logbooks which formed a line upon the shelves.

Leaning on the table, he rapidly turned over the leaves of this volume until he came to

the entry which he sought. Then, with an angry gesture of his clenched hand, he closed the

book, replaced it in the corner, and put out the light. He had hardly turned to leave the

hut when Hopkins’s hand was on the fellow’s collar, and I heard his loud gasp of

terror as he understood that he was taken. The candle was relit, and there was our

wretched captive, shivering [566] and

cowering in the grasp of the detective. He sank down upon the sea-chest, and looked

helplessly from one of us to the other. The nocturnal visitor was a young man, frail and thin, with

a black moustache, which intensified the deadly pallor of his face. He could not have been

much above twenty years of age. I have never seen any human being who appeared to be in

such a pitiable fright, for his teeth were visibly chattering, and he was shaking in every

limb. He was dressed like a gentleman, in Norfolk jacket and knickerbockers, with a cloth

cap upon his head. We watched him staring round with frightened eyes. Then he laid the

candle-end upon the table and disappeared from our view into one of the corners. He

returned with a large book, one of the logbooks which formed a line upon the shelves.

Leaning on the table, he rapidly turned over the leaves of this volume until he came to

the entry which he sought. Then, with an angry gesture of his clenched hand, he closed the

book, replaced it in the corner, and put out the light. He had hardly turned to leave the

hut when Hopkins’s hand was on the fellow’s collar, and I heard his loud gasp of

terror as he understood that he was taken. The candle was relit, and there was our

wretched captive, shivering [566] and

cowering in the grasp of the detective. He sank down upon the sea-chest, and looked

helplessly from one of us to the other.

“Now, my fine fellow,” said Stanley Hopkins,

“who are you, and what do you want here?” “Now, my fine fellow,” said Stanley Hopkins,

“who are you, and what do you want here?”

The man pulled himself together, and faced us with an effort

at self-composure. The man pulled himself together, and faced us with an effort

at self-composure.

“You are detectives, I suppose?” said he. “You

imagine I am connected with the death of Captain Peter Carey. I assure you that I am

innocent.” “You are detectives, I suppose?” said he. “You

imagine I am connected with the death of Captain Peter Carey. I assure you that I am

innocent.”

“We’ll see about that,” said Hopkins.

“First of all, what is your name?” “We’ll see about that,” said Hopkins.

“First of all, what is your name?”

“It is John Hopley Neligan.” “It is John Hopley Neligan.”

I saw Holmes and Hopkins exchange a quick glance. I saw Holmes and Hopkins exchange a quick glance.

“What are you doing here?” “What are you doing here?”

“Can I speak confidentially?” “Can I speak confidentially?”

“No, certainly not.” “No, certainly not.”

“Why should I tell you?” “Why should I tell you?”

“If you have no answer, it may go badly with you at the

trial.” “If you have no answer, it may go badly with you at the

trial.”

The young man winced. The young man winced.

“Well, I will tell you,” he said. “Why should I

not? And yet I hate to think of this old scandal gaining a new lease of life. Did you ever

hear of Dawson and Neligan?” “Well, I will tell you,” he said. “Why should I

not? And yet I hate to think of this old scandal gaining a new lease of life. Did you ever

hear of Dawson and Neligan?”

I could see, from Hopkins’s face, that he never had, but

Holmes was keenly interested. I could see, from Hopkins’s face, that he never had, but

Holmes was keenly interested.

“You mean the West Country bankers,” said he.

“They failed for a million, ruined half the county families of Cornwall, and Neligan

disappeared.” “You mean the West Country bankers,” said he.

“They failed for a million, ruined half the county families of Cornwall, and Neligan

disappeared.”

“Exactly. Neligan was my father.” “Exactly. Neligan was my father.”

At last we were getting something positive, and yet it seemed

a long gap between an absconding banker and Captain Peter Carey pinned against the wall

with one of his own harpoons. We all listened intently to the young man’s words. At last we were getting something positive, and yet it seemed

a long gap between an absconding banker and Captain Peter Carey pinned against the wall

with one of his own harpoons. We all listened intently to the young man’s words.

“It was my father who was really concerned. Dawson had

retired. I was only ten years of age at the time, but I was old enough to feel the shame

and horror of it all. It has always been said that my father stole all the securities and

fled. It is not true. It was his belief that if he were given time in which to realize

them, all would be well and every creditor paid in full. He started in his little yacht

for Norway just before the warrant was issued for his arrest. I can remember that last

night, when he bade farewell to my mother. He left us a list of the securities he was

taking, and he swore that he would come back with his honour cleared, and that none who

had trusted him would suffer. Well, no word was ever heard from him again. Both the yacht

and he vanished utterly. We believed, my mother and I, that he and it, with the securities

that he had taken with him, were at the bottom of the sea. We had a faithful friend,

however, who is a business man, and it was he who discovered some time ago that some of

the securities which my father had with him had reappeared on the London market. You can

imagine our amazement. I spent months in trying to trace them, and at last, after many

doubtings and difficulties, I discovered that the original seller had been Captain Peter

Carey, the owner of this hut. “It was my father who was really concerned. Dawson had

retired. I was only ten years of age at the time, but I was old enough to feel the shame

and horror of it all. It has always been said that my father stole all the securities and

fled. It is not true. It was his belief that if he were given time in which to realize

them, all would be well and every creditor paid in full. He started in his little yacht

for Norway just before the warrant was issued for his arrest. I can remember that last

night, when he bade farewell to my mother. He left us a list of the securities he was

taking, and he swore that he would come back with his honour cleared, and that none who

had trusted him would suffer. Well, no word was ever heard from him again. Both the yacht

and he vanished utterly. We believed, my mother and I, that he and it, with the securities

that he had taken with him, were at the bottom of the sea. We had a faithful friend,

however, who is a business man, and it was he who discovered some time ago that some of

the securities which my father had with him had reappeared on the London market. You can

imagine our amazement. I spent months in trying to trace them, and at last, after many

doubtings and difficulties, I discovered that the original seller had been Captain Peter

Carey, the owner of this hut.

“Naturally, I made some inquiries about the man. I found

that he had been in command of a whaler which was due to return from the Arctic seas at

the very time when my father was crossing to Norway. The autumn of that year was a stormy

one, and there was a long succession of southerly gales. My father’s yacht may well

have been blown to the north, and there met by Captain Peter Carey’s [567] ship. If that were so, what

had become of my father? In any case, if I could prove from Peter Carey’s evidence

how these securities came on the market it would be a proof that my father had not sold

them, and that he had no view to personal profit when he took them. “Naturally, I made some inquiries about the man. I found

that he had been in command of a whaler which was due to return from the Arctic seas at

the very time when my father was crossing to Norway. The autumn of that year was a stormy

one, and there was a long succession of southerly gales. My father’s yacht may well

have been blown to the north, and there met by Captain Peter Carey’s [567] ship. If that were so, what

had become of my father? In any case, if I could prove from Peter Carey’s evidence

how these securities came on the market it would be a proof that my father had not sold

them, and that he had no view to personal profit when he took them.

“I came down to Sussex with the intention of seeing the

captain, but it was at this moment that his terrible death occurred. I read at the inquest

a description of his cabin, in which it stated that the old logbooks of his vessel were

preserved in it. It struck me that if I could see what occurred in the month of August,

1883, on board the Sea Unicorn, I might settle the mystery of my father’s

fate. I tried last night to get at these logbooks, but was unable to open the door.

To-night I tried again and succeeded, but I find that the pages which deal with that month

have been torn from the book. It was at that moment I found myself a prisoner in your

hands.” “I came down to Sussex with the intention of seeing the

captain, but it was at this moment that his terrible death occurred. I read at the inquest

a description of his cabin, in which it stated that the old logbooks of his vessel were

preserved in it. It struck me that if I could see what occurred in the month of August,

1883, on board the Sea Unicorn, I might settle the mystery of my father’s

fate. I tried last night to get at these logbooks, but was unable to open the door.

To-night I tried again and succeeded, but I find that the pages which deal with that month

have been torn from the book. It was at that moment I found myself a prisoner in your

hands.”

“Is that all?” asked Hopkins. “Is that all?” asked Hopkins.

“Yes, that is all.” His eyes shifted as he said it. “Yes, that is all.” His eyes shifted as he said it.

“You have nothing else to tell us?” “You have nothing else to tell us?”

He hesitated. He hesitated.

“No, there is nothing.” “No, there is nothing.”

“You have not been here before last night?” “You have not been here before last night?”

“No.” “No.”

“Then how do you account for that?” cried

Hopkins, as he held up the damning notebook, with the initials of our prisoner on the

first leaf and the blood-stain on the cover. “Then how do you account for that?” cried

Hopkins, as he held up the damning notebook, with the initials of our prisoner on the

first leaf and the blood-stain on the cover.

The wretched man collapsed. He sank his face in his hands, and

trembled all over. The wretched man collapsed. He sank his face in his hands, and

trembled all over.

“Where did you get it?” he groaned. “I did not

know. I thought I had lost it at the hotel.” “Where did you get it?” he groaned. “I did not

know. I thought I had lost it at the hotel.”

“That is enough,” said Hopkins, sternly.

“Whatever else you have to say, you must say in court. You will walk down with me now

to the police-station. Well, Mr. Holmes, I am very much obliged to you and to your friend

for coming down to help me. As it turns out your presence was unnecessary, and I would

have brought the case to this successful issue without you, but, none the less, I am

grateful. Rooms have been reserved for you at the Brambletye Hotel, so we can all walk

down to the village together.” “That is enough,” said Hopkins, sternly.

“Whatever else you have to say, you must say in court. You will walk down with me now

to the police-station. Well, Mr. Holmes, I am very much obliged to you and to your friend

for coming down to help me. As it turns out your presence was unnecessary, and I would

have brought the case to this successful issue without you, but, none the less, I am

grateful. Rooms have been reserved for you at the Brambletye Hotel, so we can all walk

down to the village together.”

“Well, Watson, what do you think of it?” asked

Holmes, as we travelled back next morning. “Well, Watson, what do you think of it?” asked

Holmes, as we travelled back next morning.

“I can see that you are not satisfied.” “I can see that you are not satisfied.”

“Oh, yes, my dear Watson, I am perfectly satisfied. At

the same time, Stanley Hopkins’s methods do not commend themselves to me. I am

disappointed in Stanley Hopkins. I had hoped for better things from him. One should always

look for a possible alternative, and provide against it. It is the first rule of criminal

investigation.” “Oh, yes, my dear Watson, I am perfectly satisfied. At

the same time, Stanley Hopkins’s methods do not commend themselves to me. I am

disappointed in Stanley Hopkins. I had hoped for better things from him. One should always

look for a possible alternative, and provide against it. It is the first rule of criminal

investigation.”

“What, then, is the alternative?” “What, then, is the alternative?”

“The line of investigation which I have myself been

pursuing. It may give us nothing. I cannot tell. But at least I shall follow it to the

end.” “The line of investigation which I have myself been

pursuing. It may give us nothing. I cannot tell. But at least I shall follow it to the

end.”

Several letters were waiting for Holmes at Baker Street. He

snatched one of them up, opened it, and burst out into a triumphant chuckle of laughter. Several letters were waiting for Holmes at Baker Street. He

snatched one of them up, opened it, and burst out into a triumphant chuckle of laughter.

“Excellent, Watson! The alternative develops. Have you

telegraph forms? Just write a couple of messages for me: ‘Sumner, Shipping Agent,

Ratcliff Highway. [568] Send

three men on, to arrive ten to-morrow morning.–Basil.’ That’s my name in

those parts. The other is: ‘Inspector Stanley Hopkins, 46 Lord Street, Brixton. Come

breakfast to-morrow at nine-thirty. Important. Wire if unable to come.–Sherlock

Holmes.’ There, Watson, this infernal case has haunted me for ten days. I hereby

banish it completely from my presence. To-morrow, I trust that we shall hear the last of

it forever.” “Excellent, Watson! The alternative develops. Have you

telegraph forms? Just write a couple of messages for me: ‘Sumner, Shipping Agent,

Ratcliff Highway. [568] Send

three men on, to arrive ten to-morrow morning.–Basil.’ That’s my name in

those parts. The other is: ‘Inspector Stanley Hopkins, 46 Lord Street, Brixton. Come

breakfast to-morrow at nine-thirty. Important. Wire if unable to come.–Sherlock

Holmes.’ There, Watson, this infernal case has haunted me for ten days. I hereby

banish it completely from my presence. To-morrow, I trust that we shall hear the last of

it forever.”

Sharp at the hour named Inspector Stanley Hopkins appeared,

and we sat down together to the excellent breakfast which Mrs. Hudson had prepared. The

young detective was in high spirits at his success. Sharp at the hour named Inspector Stanley Hopkins appeared,

and we sat down together to the excellent breakfast which Mrs. Hudson had prepared. The

young detective was in high spirits at his success.

“You really think that your solution must be

correct?” asked Holmes. “You really think that your solution must be

correct?” asked Holmes.

“I could not imagine a more complete case.” “I could not imagine a more complete case.”

“It did not seem to me conclusive.” “It did not seem to me conclusive.”

“You astonish me, Mr. Holmes. What more could one ask

for?” “You astonish me, Mr. Holmes. What more could one ask

for?”

“Does your explanation cover every point?” “Does your explanation cover every point?”

“Undoubtedly. I find that young Neligan arrived at the

Brambletye Hotel on the very day of the crime. He came on the pretence of playing golf.

His room was on the ground-floor, and he could get out when he liked. That very night he

went down to Woodman’s Lee, saw Peter Carey at the hut, quarrelled with him, and

killed him with the harpoon. Then, horrified by what he had done, he fled out of the hut,

dropping the notebook which he had brought with him in order to question Peter Carey about

these different securities. You may have observed that some of them were marked with

ticks, and the others–the great majority –were not. Those which are ticked have

been traced on the London market, but the others, presumably, were still in the possession

of Carey, and young Neligan, according to his own account, was anxious to recover them in

order to do the right thing by his father’s creditors. After his flight he did not

dare to approach the hut again for some time, but at last he forced himself to do so in

order to obtain the information which he needed. Surely that is all simple and

obvious?” “Undoubtedly. I find that young Neligan arrived at the

Brambletye Hotel on the very day of the crime. He came on the pretence of playing golf.

His room was on the ground-floor, and he could get out when he liked. That very night he

went down to Woodman’s Lee, saw Peter Carey at the hut, quarrelled with him, and

killed him with the harpoon. Then, horrified by what he had done, he fled out of the hut,

dropping the notebook which he had brought with him in order to question Peter Carey about

these different securities. You may have observed that some of them were marked with

ticks, and the others–the great majority –were not. Those which are ticked have

been traced on the London market, but the others, presumably, were still in the possession

of Carey, and young Neligan, according to his own account, was anxious to recover them in

order to do the right thing by his father’s creditors. After his flight he did not

dare to approach the hut again for some time, but at last he forced himself to do so in

order to obtain the information which he needed. Surely that is all simple and

obvious?”

Holmes smiled and shook his head. Holmes smiled and shook his head.

“It seems to me to have only one drawback, Hopkins, and

that is that it is intrinsically impossible. Have you tried to drive a harpoon through a

body? No? Tut, tut, my dear sir, you must really pay attention to these details. My friend

Watson could tell you that I spent a whole morning in that exercise. It is no easy matter,

and requires a strong and practised arm. But this blow was delivered with such violence

that the head of the weapon sank deep into the wall. Do you imagine that this anaemic

youth was capable of so frightful an assault? Is he the man who hobnobbed in rum and water

with Black Peter in the dead of the night? Was it his profile that was seen on the blind

two nights before? No, no, Hopkins, it is another and more formidable person for whom we

must seek.” “It seems to me to have only one drawback, Hopkins, and

that is that it is intrinsically impossible. Have you tried to drive a harpoon through a

body? No? Tut, tut, my dear sir, you must really pay attention to these details. My friend

Watson could tell you that I spent a whole morning in that exercise. It is no easy matter,

and requires a strong and practised arm. But this blow was delivered with such violence

that the head of the weapon sank deep into the wall. Do you imagine that this anaemic

youth was capable of so frightful an assault? Is he the man who hobnobbed in rum and water

with Black Peter in the dead of the night? Was it his profile that was seen on the blind

two nights before? No, no, Hopkins, it is another and more formidable person for whom we

must seek.”

The detective’s face had grown longer and longer during

Holmes’s speech. His hopes and his ambitions were all crumbling about him. But he

would not abandon his position without a struggle. The detective’s face had grown longer and longer during

Holmes’s speech. His hopes and his ambitions were all crumbling about him. But he

would not abandon his position without a struggle.

“You can’t deny that Neligan was present that night,

Mr. Holmes. The book will prove that. I fancy that I have evidence enough to satisfy a

jury, even if you are able to pick a hole in it. Besides, Mr. Holmes, I have laid my hand

upon my man. As to this terrible person of yours, where is he?” “You can’t deny that Neligan was present that night,

Mr. Holmes. The book will prove that. I fancy that I have evidence enough to satisfy a

jury, even if you are able to pick a hole in it. Besides, Mr. Holmes, I have laid my hand

upon my man. As to this terrible person of yours, where is he?”

“I rather fancy that he is on the stair,” said

Holmes, serenely. “I think, Watson, that you would do well to put that revolver where

you can reach it.” He rose and laid a written paper upon a side-table. “Now we

are ready,” said he. “I rather fancy that he is on the stair,” said

Holmes, serenely. “I think, Watson, that you would do well to put that revolver where

you can reach it.” He rose and laid a written paper upon a side-table. “Now we

are ready,” said he.

[569] There

had been some talking in gruff voices outside, and now Mrs. Hudson opened the door to say

that there were three men inquiring for Captain Basil. [569] There

had been some talking in gruff voices outside, and now Mrs. Hudson opened the door to say

that there were three men inquiring for Captain Basil.

“Show them in one by one,” said Holmes. “Show them in one by one,” said Holmes.

The first who entered was a little Ribston pippin of a man,

with ruddy cheeks and fluffy white side-whiskers. Holmes had drawn a letter from his

pocket. The first who entered was a little Ribston pippin of a man,

with ruddy cheeks and fluffy white side-whiskers. Holmes had drawn a letter from his

pocket.

“What name?” he asked. “What name?” he asked.

“James Lancaster.” “James Lancaster.”

“I am sorry, Lancaster, but the berth is full. Here is

half a sovereign for your trouble. Just step into this room and wait there for a few

minutes.” “I am sorry, Lancaster, but the berth is full. Here is

half a sovereign for your trouble. Just step into this room and wait there for a few

minutes.”

The second man was a long, dried-up creature, with lank hair

and sallow cheeks. His name was Hugh Pattins. He also received his dismissal, his

half-sovereign, and the order to wait. The second man was a long, dried-up creature, with lank hair

and sallow cheeks. His name was Hugh Pattins. He also received his dismissal, his

half-sovereign, and the order to wait.

The third applicant was a man of remarkable appearance. A

fierce bull-dog face was framed in a tangle of hair and beard, and two bold, dark eyes

gleamed behind the cover of thick, tufted, overhung eyebrows. He saluted and stood

sailor-fashion, turning his cap round in his hands. The third applicant was a man of remarkable appearance. A

fierce bull-dog face was framed in a tangle of hair and beard, and two bold, dark eyes

gleamed behind the cover of thick, tufted, overhung eyebrows. He saluted and stood

sailor-fashion, turning his cap round in his hands.

“Your name?” asked Holmes. “Your name?” asked Holmes.

“Patrick Cairns.” “Patrick Cairns.”

“Harpooner?” “Harpooner?”

“Yes, sir. Twenty-six voyages.” “Yes, sir. Twenty-six voyages.”

“Dundee, I suppose?” “Dundee, I suppose?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“And ready to start with an exploring ship?” “And ready to start with an exploring ship?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“What wages?” “What wages?”

“Eight pounds a month.” “Eight pounds a month.”

“Could you start at once?” “Could you start at once?”

“As soon as I get my kit.” “As soon as I get my kit.”

“Have you your papers?” “Have you your papers?”

“Yes, sir.” He took a sheaf of worn and greasy forms

from his pocket. Holmes glanced over them and returned them. “Yes, sir.” He took a sheaf of worn and greasy forms

from his pocket. Holmes glanced over them and returned them.

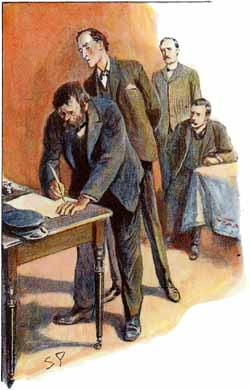

“You are just the man I want,” said he.

“Here’s the agreement on the side-table. If you sign it the whole matter will be

settled.” “You are just the man I want,” said he.

“Here’s the agreement on the side-table. If you sign it the whole matter will be

settled.”

The seaman lurched across the room and took up the pen. The seaman lurched across the room and took up the pen.

“Shall I sign here?” he asked, stooping over the

table. “Shall I sign here?” he asked, stooping over the

table.

Holmes leaned over his shoulder and passed both hands over

his neck. Holmes leaned over his shoulder and passed both hands over

his neck.

“This will do,” said he. “This will do,” said he.

I heard a click of steel and a bellow like an enraged bull.

The next instant Holmes and the seaman were rolling on the ground together. He was a man

of such gigantic strength that, even with the handcuffs which Holmes had so deftly

fastened upon his wrists, he would have very quickly overpowered my friend had Hopkins and

I not rushed to his rescue. Only when I pressed the cold muzzle of the revolver to his

temple did he at last understand that resistance was vain. We lashed his ankles with cord,

and rose breathless from the struggle. I heard a click of steel and a bellow like an enraged bull.

The next instant Holmes and the seaman were rolling on the ground together. He was a man

of such gigantic strength that, even with the handcuffs which Holmes had so deftly

fastened upon his wrists, he would have very quickly overpowered my friend had Hopkins and

I not rushed to his rescue. Only when I pressed the cold muzzle of the revolver to his

temple did he at last understand that resistance was vain. We lashed his ankles with cord,

and rose breathless from the struggle.

“I must really apologize, Hopkins,” said Sherlock

Holmes. “I fear that the scrambled eggs are cold. However, you will enjoy the rest of

your breakfast all the better, will you not, for the thought that you have brought your

case to a triumphant conclusion.” “I must really apologize, Hopkins,” said Sherlock

Holmes. “I fear that the scrambled eggs are cold. However, you will enjoy the rest of

your breakfast all the better, will you not, for the thought that you have brought your

case to a triumphant conclusion.”

Stanley Hopkins was speechless with amazement. Stanley Hopkins was speechless with amazement.

[570] “I

don’t know what to say, Mr. Holmes,” he blurted out at last, with a very red

face. “It seems to me that I have been making a fool of myself from the beginning. I

understand now, what I should never have forgotten, that I am the pupil and you are the

master. Even now I see what you have done, but I don’t know how you did it or what it

signifies.” [570] “I

don’t know what to say, Mr. Holmes,” he blurted out at last, with a very red

face. “It seems to me that I have been making a fool of myself from the beginning. I

understand now, what I should never have forgotten, that I am the pupil and you are the

master. Even now I see what you have done, but I don’t know how you did it or what it

signifies.”

“Well, well,” said Holmes, good-humouredly. “We

all learn by experience, and your lesson this time is that you should never lose sight of

the alternative. You were so absorbed in young Neligan that you could not spare a thought

to Patrick Cairns, the true murderer of Peter Carey.” “Well, well,” said Holmes, good-humouredly. “We

all learn by experience, and your lesson this time is that you should never lose sight of

the alternative. You were so absorbed in young Neligan that you could not spare a thought

to Patrick Cairns, the true murderer of Peter Carey.”

The hoarse voice of the seaman broke in on our conversation. The hoarse voice of the seaman broke in on our conversation.

“See here, mister,” said he, “I make no

complaint of being man-handled in this fashion, but I would have you call things by their

right names. You say I murdered Peter Carey, I say I killed Peter Carey, and

there’s all the difference. Maybe you don’t believe what I say. Maybe you think

I am just slinging you a yarn.” “See here, mister,” said he, “I make no

complaint of being man-handled in this fashion, but I would have you call things by their

right names. You say I murdered Peter Carey, I say I killed Peter Carey, and

there’s all the difference. Maybe you don’t believe what I say. Maybe you think

I am just slinging you a yarn.”

“Not at all,” said Holmes. “Let us hear what

you have to say.” “Not at all,” said Holmes. “Let us hear what

you have to say.”

“It’s soon told, and, by the Lord, every word of it

is truth. I knew Black Peter, and when he pulled out his knife I whipped a harpoon through

him sharp, for I knew that it was him or me. That’s how he died. You can call it

murder. Anyhow, I’d as soon die with a rope round my neck as with Black Peter’s

knife in my heart.” “It’s soon told, and, by the Lord, every word of it

is truth. I knew Black Peter, and when he pulled out his knife I whipped a harpoon through

him sharp, for I knew that it was him or me. That’s how he died. You can call it

murder. Anyhow, I’d as soon die with a rope round my neck as with Black Peter’s

knife in my heart.”

“How came you there?” asked Holmes. “How came you there?” asked Holmes.

“I’ll tell it you from the beginning. Just sit me up

a little, so as I can speak easy. It was in ’83 that it happened–August of that

year. Peter Carey was master of the Sea Unicorn, and I was spare harpooner. We

were coming out of the ice-pack on our way home, with head winds and a week’s

southerly gale, when we picked up a little craft that had been blown north. There was one

man on her –a landsman. The crew had thought she would founder and had made for the

Norwegian coast in the dinghy. I guess they were all drowned. Well, we took him on board,

this man, and he and the skipper had some long talks in the cabin. All the baggage we took

off with him was one tin box. So far as I know, the man’s name was never mentioned,

and on the second night he disappeared as if he had never been. It was given out that he

had either thrown himself overboard or fallen overboard in the heavy weather that we were

having. Only one man knew what had happened to him, and that was me, for, with my own

eyes, I saw the skipper tip up his heels and put him over the rail in the middle watch of

a dark night, two days before we sighted the Shetland Lights. “I’ll tell it you from the beginning. Just sit me up

a little, so as I can speak easy. It was in ’83 that it happened–August of that

year. Peter Carey was master of the Sea Unicorn, and I was spare harpooner. We

were coming out of the ice-pack on our way home, with head winds and a week’s

southerly gale, when we picked up a little craft that had been blown north. There was one

man on her –a landsman. The crew had thought she would founder and had made for the

Norwegian coast in the dinghy. I guess they were all drowned. Well, we took him on board,

this man, and he and the skipper had some long talks in the cabin. All the baggage we took

off with him was one tin box. So far as I know, the man’s name was never mentioned,

and on the second night he disappeared as if he had never been. It was given out that he

had either thrown himself overboard or fallen overboard in the heavy weather that we were

having. Only one man knew what had happened to him, and that was me, for, with my own

eyes, I saw the skipper tip up his heels and put him over the rail in the middle watch of

a dark night, two days before we sighted the Shetland Lights.

”Well, I kept my knowledge to myself, and waited to see

what would come of it. When we got back to Scotland it was easily hushed up, and nobody

asked any questions. A stranger died by accident, and it was nobody’s business to

inquire. Shortly after Peter Carey gave up the sea, and it was long years before I could

find where he was. I guessed that he had done the deed for the sake of what was in that

tin box, and that he could afford now to pay me well for keeping my mouth shut. ”Well, I kept my knowledge to myself, and waited to see

what would come of it. When we got back to Scotland it was easily hushed up, and nobody

asked any questions. A stranger died by accident, and it was nobody’s business to

inquire. Shortly after Peter Carey gave up the sea, and it was long years before I could

find where he was. I guessed that he had done the deed for the sake of what was in that

tin box, and that he could afford now to pay me well for keeping my mouth shut.

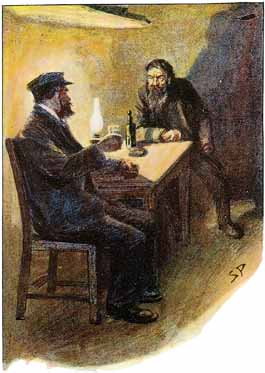

“I found out where he was through a sailor man that

had met him in London, and down I went to squeeze him. The first night he was reasonable

enough, and was ready to give me what would make me free of the sea for life. We were to

fix it all two nights later. When I came, I found him three parts drunk and in a vile

temper. We sat down and we drank and we yarned about old times, but the more he drank the

less I liked the look on his face. I spotted that harpoon upon the wall, and I thought I

might need it before I was through. Then at last he broke out at [571] me, spitting and cursing, with murder in his eyes and a

great clasp-knife in his hand. He had not time to get it from the sheath before I had the

harpoon through him. Heavens! what a yell he gave! and his face gets between me and my

sleep. I stood there, with his blood splashing round me, and I waited for a bit, but all

was quiet, so I took heart once more. I looked round, and there was the tin box on the

shelf. I had as much right to it as Peter Carey, anyhow, so I took it with me and left the

hut. Like a fool I left my baccy-pouch upon the table. “I found out where he was through a sailor man that

had met him in London, and down I went to squeeze him. The first night he was reasonable

enough, and was ready to give me what would make me free of the sea for life. We were to

fix it all two nights later. When I came, I found him three parts drunk and in a vile

temper. We sat down and we drank and we yarned about old times, but the more he drank the

less I liked the look on his face. I spotted that harpoon upon the wall, and I thought I

might need it before I was through. Then at last he broke out at [571] me, spitting and cursing, with murder in his eyes and a