|

|

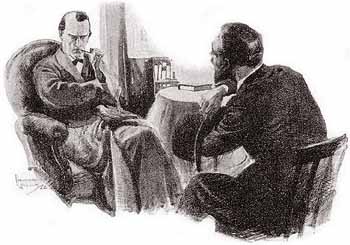

I lit my pipe and leaned back in my chair. I lit my pipe and leaned back in my chair.

“Perhaps you will explain what you are talking

about.” “Perhaps you will explain what you are talking

about.”

My client grinned mischievously. My client grinned mischievously.

“I had got into the way of supposing that you knew

everything without being told,” said he. “But I will give you the facts, and I

hope to God that you will be able to tell me what they mean. I’ve been awake all

night puzzling my brain, and the more I think the more incredible does it become. “I had got into the way of supposing that you knew

everything without being told,” said he. “But I will give you the facts, and I

hope to God that you will be able to tell me what they mean. I’ve been awake all

night puzzling my brain, and the more I think the more incredible does it become.

“When I joined up in January, 1901–just two years

ago–young Godfrey Emsworth had joined the same squadron. He was Colonel

Emsworth’s only son– Emsworth, the Crimean V. C.–and he had the fighting

blood in him, so it is no wonder he volunteered. There was not a finer lad in the

regiment. We formed a friendship–the sort of friendship which can only be made when

one lives the same life and shares the same joys and sorrows. He was my mate–and that

means a good deal in the Army. We took the rough and the smooth together for a year of

hard fighting. Then he was hit with a bullet from an elephant gun in the action near

Diamond Hill outside Pretoria. I got one letter from the hospital at Cape Town and one

from Southampton. Since then not a word–not one word, Mr. Holmes, for six months and

more, and he my closest pal. “When I joined up in January, 1901–just two years

ago–young Godfrey Emsworth had joined the same squadron. He was Colonel

Emsworth’s only son– Emsworth, the Crimean V. C.–and he had the fighting

blood in him, so it is no wonder he volunteered. There was not a finer lad in the

regiment. We formed a friendship–the sort of friendship which can only be made when

one lives the same life and shares the same joys and sorrows. He was my mate–and that

means a good deal in the Army. We took the rough and the smooth together for a year of

hard fighting. Then he was hit with a bullet from an elephant gun in the action near

Diamond Hill outside Pretoria. I got one letter from the hospital at Cape Town and one

from Southampton. Since then not a word–not one word, Mr. Holmes, for six months and

more, and he my closest pal.

“Well, when the war was over, and we all got back, I

wrote to his father and asked where Godfrey was. No answer. I waited a bit and then I

wrote again. This time I had a reply, short and gruff. Godfrey had gone on a voyage round

the world, and it was not likely that he would be back for a year. That was all. “Well, when the war was over, and we all got back, I

wrote to his father and asked where Godfrey was. No answer. I waited a bit and then I

wrote again. This time I had a reply, short and gruff. Godfrey had gone on a voyage round

the world, and it was not likely that he would be back for a year. That was all.

“I wasn’t satisfied, Mr. Holmes. The whole thing

seemed to me so damned unnatural. He was a good lad, and he would not drop a pal like

that. It was not like him. Then, again, I happened to know that he was heir to a lot of

money, and also that his father and he did not always hit it off too well. The old man was

sometimes a bully, and young Godfrey had too much spirit to stand it. No, I wasn’t

satisfied, and I determined that I would get to the root of the matter. It happened,

however, that my own affairs needed a lot of straightening out, after two years’

absence, and so it is only this week that I have been able to take up Godfrey’s case

again. But since I have taken it up I mean to drop everything in order to see it

through.” “I wasn’t satisfied, Mr. Holmes. The whole thing

seemed to me so damned unnatural. He was a good lad, and he would not drop a pal like

that. It was not like him. Then, again, I happened to know that he was heir to a lot of

money, and also that his father and he did not always hit it off too well. The old man was

sometimes a bully, and young Godfrey had too much spirit to stand it. No, I wasn’t

satisfied, and I determined that I would get to the root of the matter. It happened,

however, that my own affairs needed a lot of straightening out, after two years’

absence, and so it is only this week that I have been able to take up Godfrey’s case

again. But since I have taken it up I mean to drop everything in order to see it

through.”

Mr. James M. Dodd appeared to be the sort of person whom it

would be better to have as a friend than as an enemy. His blue eyes were stern and his

square jaw had set hard as he spoke. Mr. James M. Dodd appeared to be the sort of person whom it

would be better to have as a friend than as an enemy. His blue eyes were stern and his

square jaw had set hard as he spoke.

“Well, what have you done?” I asked. “Well, what have you done?” I asked.

“My first move was to get down to his home, Tuxbury Old

Park, near Bedford, and to see for myself how the ground lay. I wrote to the mother,

therefore–I had had quite enough of the curmudgeon of a father–and I made a

clean frontal [1002] attack:

Godfrey was my chum, I had a great deal of interest which I might tell her of our common

experiences, I should be in the neighbourhood, would there be any objection, et cetera? In

reply I had quite an amiable answer from her and an offer to put me up for the night. That

was what took me down on Monday. “My first move was to get down to his home, Tuxbury Old

Park, near Bedford, and to see for myself how the ground lay. I wrote to the mother,

therefore–I had had quite enough of the curmudgeon of a father–and I made a

clean frontal [1002] attack:

Godfrey was my chum, I had a great deal of interest which I might tell her of our common

experiences, I should be in the neighbourhood, would there be any objection, et cetera? In

reply I had quite an amiable answer from her and an offer to put me up for the night. That

was what took me down on Monday.

“Tuxbury Old Hall is inaccessible–five miles from

anywhere. There was no trap at the station, so I had to walk, carrying my suitcase, and it

was nearly dark before I arrived. It is a great wandering house, standing in a

considerable park. I should judge it was of all sorts of ages and styles, starting on a

half-timbered Elizabethan foundation and ending in a Victorian portico. Inside it was all

panelling and tapestry and half-effaced old pictures, a house of shadows and mystery.

There was a butler, old Ralph, who seemed about the same age as the house, and there was

his wife, who might have been older. She had been Godfrey’s nurse, and I had heard

him speak of her as second only to his mother in his affections, so I was drawn to her in

spite of her queer appearance. The mother I liked also–a gentle little white mouse of

a woman. It was only the colonel himself whom I barred. “Tuxbury Old Hall is inaccessible–five miles from

anywhere. There was no trap at the station, so I had to walk, carrying my suitcase, and it

was nearly dark before I arrived. It is a great wandering house, standing in a

considerable park. I should judge it was of all sorts of ages and styles, starting on a

half-timbered Elizabethan foundation and ending in a Victorian portico. Inside it was all

panelling and tapestry and half-effaced old pictures, a house of shadows and mystery.

There was a butler, old Ralph, who seemed about the same age as the house, and there was

his wife, who might have been older. She had been Godfrey’s nurse, and I had heard

him speak of her as second only to his mother in his affections, so I was drawn to her in

spite of her queer appearance. The mother I liked also–a gentle little white mouse of

a woman. It was only the colonel himself whom I barred.

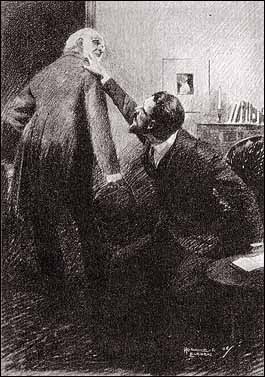

“We had a bit of barney right away, and I should have

walked back to the station if I had not felt that it might be playing his game for me to

do so. I was shown straight into his study, and there I found him, a huge, bow-backed man

with a smoky skin and a straggling gray beard, seated behind his littered desk. A

red-veined nose jutted out like a vulture’s beak, and two fierce gray eyes glared at

me from under tufted brows. I could understand now why Godfrey seldom spoke of his father. “We had a bit of barney right away, and I should have

walked back to the station if I had not felt that it might be playing his game for me to

do so. I was shown straight into his study, and there I found him, a huge, bow-backed man

with a smoky skin and a straggling gray beard, seated behind his littered desk. A

red-veined nose jutted out like a vulture’s beak, and two fierce gray eyes glared at

me from under tufted brows. I could understand now why Godfrey seldom spoke of his father.

“ ‘Well, sir,’ said he in a rasping voice,

‘I should be interested to know the real reasons for this visit.’ “ ‘Well, sir,’ said he in a rasping voice,

‘I should be interested to know the real reasons for this visit.’

“I answered that I had explained them in my letter to his

wife. “I answered that I had explained them in my letter to his

wife.

“ ‘Yes, yes, you said that you had known Godfrey in

Africa. We have, of course, only your word for that.’ “ ‘Yes, yes, you said that you had known Godfrey in

Africa. We have, of course, only your word for that.’

“ ‘I have his letters to me in my pocket.’ “ ‘I have his letters to me in my pocket.’

“ ‘Kindly let me see them.’ “ ‘Kindly let me see them.’

“He glanced at the two which I handed him, and then he

tossed them back. “He glanced at the two which I handed him, and then he

tossed them back.

“ ‘Well, what then?’ he asked. “ ‘Well, what then?’ he asked.

“ ‘I was fond of your son Godfrey, sir. Many ties

and memories united us. Is it not natural that I should wonder at his sudden silence and

should wish to know what has become of him?’ “ ‘I was fond of your son Godfrey, sir. Many ties

and memories united us. Is it not natural that I should wonder at his sudden silence and

should wish to know what has become of him?’

“ ‘I have some recollections, sir, that I had

already corresponded with you and had told you what had become of him. He has gone upon a

voyage round the world. His health was in a poor way after his African experiences, and

both his mother and I were of opinion that complete rest and change were needed. Kindly

pass that explanation on to any other friends who may be interested in the matter.’ “ ‘I have some recollections, sir, that I had

already corresponded with you and had told you what had become of him. He has gone upon a

voyage round the world. His health was in a poor way after his African experiences, and

both his mother and I were of opinion that complete rest and change were needed. Kindly

pass that explanation on to any other friends who may be interested in the matter.’

“ ‘Certainly,’ I answered. ‘But perhaps

you would have the goodness to let me have the name of the steamer and of the line by

which he sailed, together with the date. I have no doubt that I should be able to get a

letter through to him.’ “ ‘Certainly,’ I answered. ‘But perhaps

you would have the goodness to let me have the name of the steamer and of the line by

which he sailed, together with the date. I have no doubt that I should be able to get a

letter through to him.’

“My request seemed both to puzzle and to irritate my

host. His great eyebrows came down over his eyes, and he tapped his fingers impatiently on

the table. He looked up at last with the expression of one who has seen his adversary make

a dangerous move at chess, and has decided how to meet it. “My request seemed both to puzzle and to irritate my

host. His great eyebrows came down over his eyes, and he tapped his fingers impatiently on

the table. He looked up at last with the expression of one who has seen his adversary make

a dangerous move at chess, and has decided how to meet it.

“ ‘Many people, Mr. Dodd,’ said he, ‘would

take offence at your infernal pertinacity and would think that this insistence had reached

the point of damned impertinence.’ “ ‘Many people, Mr. Dodd,’ said he, ‘would

take offence at your infernal pertinacity and would think that this insistence had reached

the point of damned impertinence.’

[1003] “

‘You must put it down, sir, to my real love for your son.’ [1003] “

‘You must put it down, sir, to my real love for your son.’

“ ‘Exactly. I have already made every allowance upon

that score. I must ask you, however, to drop these inquiries. Every family has its own

inner knowledge and its own motives, which cannot always be made clear to outsiders,

however well-intentioned. My wife is anxious to hear something of Godfrey’s past

which you are in a position to tell her, but I would ask you to let the present and the

future alone. Such inquiries serve no useful purpose, sir, and place us in a delicate and

difficult position.’ “ ‘Exactly. I have already made every allowance upon

that score. I must ask you, however, to drop these inquiries. Every family has its own

inner knowledge and its own motives, which cannot always be made clear to outsiders,

however well-intentioned. My wife is anxious to hear something of Godfrey’s past

which you are in a position to tell her, but I would ask you to let the present and the

future alone. Such inquiries serve no useful purpose, sir, and place us in a delicate and

difficult position.’

“So I came to a dead end, Mr. Holmes. There was no

getting past it. I could only pretend to accept the situation and register a vow inwardly

that I would never rest until my friend’s fate had been cleared up. It was a dull

evening. We dined quietly, the three of us, in a gloomy, faded old room. The lady

questioned me eagerly about her son, but the old man seemed morose and depressed. I was so

bored by the whole proceeding that I made an excuse as soon as I decently could and

retired to my bedroom. It was a large, bare room on the ground floor, as gloomy as the

rest of the house, but after a year of sleeping upon the veldt, Mr. Holmes, one is not too

particular about one’s quarters. I opened the curtains and looked out into the

garden, remarking that it was a fine night with a bright half-moon. Then I sat down by the

roaring fire with the lamp on a table beside me, and endeavoured to distract my mind with

a novel. I was interrupted, however, by Ralph, the old butler, who came in with a fresh

supply of coals. “So I came to a dead end, Mr. Holmes. There was no

getting past it. I could only pretend to accept the situation and register a vow inwardly

that I would never rest until my friend’s fate had been cleared up. It was a dull

evening. We dined quietly, the three of us, in a gloomy, faded old room. The lady

questioned me eagerly about her son, but the old man seemed morose and depressed. I was so

bored by the whole proceeding that I made an excuse as soon as I decently could and

retired to my bedroom. It was a large, bare room on the ground floor, as gloomy as the

rest of the house, but after a year of sleeping upon the veldt, Mr. Holmes, one is not too

particular about one’s quarters. I opened the curtains and looked out into the

garden, remarking that it was a fine night with a bright half-moon. Then I sat down by the

roaring fire with the lamp on a table beside me, and endeavoured to distract my mind with

a novel. I was interrupted, however, by Ralph, the old butler, who came in with a fresh

supply of coals.

“ ‘I thought you might run short in the night-time,

sir. It is bitter weather and these rooms are cold.’ “ ‘I thought you might run short in the night-time,

sir. It is bitter weather and these rooms are cold.’

“He hesitated before leaving the room, and when I looked

round he was standing facing me with a wistful look upon his wrinkled face. “He hesitated before leaving the room, and when I looked

round he was standing facing me with a wistful look upon his wrinkled face.

“ ‘Beg your pardon, sir, but I could not help

hearing what you said of young Master Godfrey at dinner. You know, sir, that my wife

nursed him, and so I may say I am his foster-father. It’s natural we should take an

interest. And you say he carried himself well, sir?’ “ ‘Beg your pardon, sir, but I could not help

hearing what you said of young Master Godfrey at dinner. You know, sir, that my wife

nursed him, and so I may say I am his foster-father. It’s natural we should take an

interest. And you say he carried himself well, sir?’

“ ‘There was no braver man in the regiment. He

pulled me out once from under the rifles of the Boers, or maybe I should not be

here.’ “ ‘There was no braver man in the regiment. He

pulled me out once from under the rifles of the Boers, or maybe I should not be

here.’

“The old butler rubbed his skinny hands. “The old butler rubbed his skinny hands.

“ ‘Yes, sir, yes, that is Master Godfrey all over.

He was always courageous. There’s not a tree in the park, sir, that he has not

climbed. Nothing would stop him. He was a fine boy–and oh, sir, he was a fine

man.’ “ ‘Yes, sir, yes, that is Master Godfrey all over.

He was always courageous. There’s not a tree in the park, sir, that he has not

climbed. Nothing would stop him. He was a fine boy–and oh, sir, he was a fine

man.’

“I sprang to my feet. “I sprang to my feet.

“ ‘Look here!’ I cried. ‘You say he was.

You speak as if he were dead. What is all this mystery? What has become of Godfrey

Emsworth?’ “ ‘Look here!’ I cried. ‘You say he was.

You speak as if he were dead. What is all this mystery? What has become of Godfrey

Emsworth?’

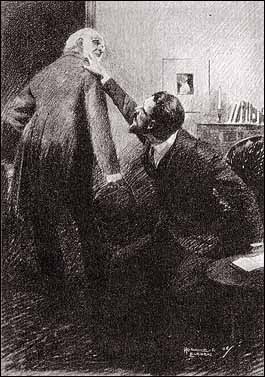

“I gripped the old man by the shoulder, but he shrank

away. “I gripped the old man by the shoulder, but he shrank

away.

“ ‘I don’t know what you mean, sir. Ask the

master about Master Godfrey. He knows. It is not for me to interfere.’ “ ‘I don’t know what you mean, sir. Ask the

master about Master Godfrey. He knows. It is not for me to interfere.’

“He was leaving the room, but I held his arm. “He was leaving the room, but I held his arm.

“ ‘Listen,’ I said. ‘You are going to

answer one question before you leave if I have to hold you all night. Is Godfrey

dead?’ “ ‘Listen,’ I said. ‘You are going to

answer one question before you leave if I have to hold you all night. Is Godfrey

dead?’

“He could not face my eyes. He was like a man hypnotized.

The answer was dragged from his lips. It was a terrible and unexpected one. “He could not face my eyes. He was like a man hypnotized.

The answer was dragged from his lips. It was a terrible and unexpected one.

“ ‘I wish to God he was!’ he cried, and,

tearing himself free, he dashed from the room. “ ‘I wish to God he was!’ he cried, and,

tearing himself free, he dashed from the room.

“You will think, Mr. Holmes, that I returned to my chair

in no very happy [1004] state

of mind. The old man’s words seemed to me to bear only one interpretation. Clearly my

poor friend had become involved in some criminal or, at the least, disreputable

transaction which touched the family honour. That stern old man had sent his son away and

hidden him from the world lest some scandal should come to light. Godfrey was a reckless

fellow. He was easily influenced by those around him. No doubt he had fallen into bad

hands and been misled to his ruin. It was a piteous business, if it was indeed so, but

even now it was my duty to hunt him out and see if I could aid him. I was anxiously

pondering the matter when I looked up, and there was Godfrey Emsworth standing before

me.” “You will think, Mr. Holmes, that I returned to my chair

in no very happy [1004] state

of mind. The old man’s words seemed to me to bear only one interpretation. Clearly my

poor friend had become involved in some criminal or, at the least, disreputable

transaction which touched the family honour. That stern old man had sent his son away and

hidden him from the world lest some scandal should come to light. Godfrey was a reckless

fellow. He was easily influenced by those around him. No doubt he had fallen into bad

hands and been misled to his ruin. It was a piteous business, if it was indeed so, but

even now it was my duty to hunt him out and see if I could aid him. I was anxiously

pondering the matter when I looked up, and there was Godfrey Emsworth standing before

me.”

My client had paused as one in deep emotion. My client had paused as one in deep emotion.

“Pray continue,” I said. “Your problem presents

some very unusual features.” “Pray continue,” I said. “Your problem presents

some very unusual features.”

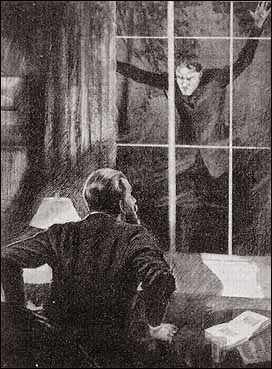

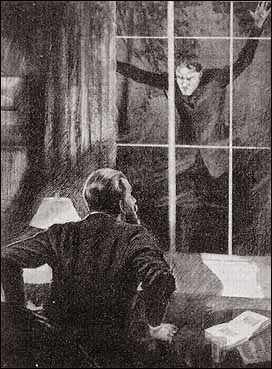

“He was outside the window, Mr. Holmes, with his face

pressed against the glass. I have told you that I looked out at the night. When I did so I

left the curtains partly open. His figure was framed in this gap. The window came down to

the ground and I could see the whole length of it, but it was his face which held my gaze.

He was deadly pale–never have I seen a man so white. I reckon ghosts may look like

that; but his eyes met mine, and they were the eyes of a living man. He sprang back when

he saw that I was looking at him, and he vanished into the darkness. “He was outside the window, Mr. Holmes, with his face

pressed against the glass. I have told you that I looked out at the night. When I did so I

left the curtains partly open. His figure was framed in this gap. The window came down to

the ground and I could see the whole length of it, but it was his face which held my gaze.

He was deadly pale–never have I seen a man so white. I reckon ghosts may look like

that; but his eyes met mine, and they were the eyes of a living man. He sprang back when

he saw that I was looking at him, and he vanished into the darkness.

“There was something shocking about the man, Mr.

Holmes. It wasn’t merely that ghastly face glimmering as white as cheese in the

darkness. It was more subtle than that–something slinking, something furtive,

something guilty– something very unlike the frank, manly lad that I had known. It

left a feeling of horror in my mind. “There was something shocking about the man, Mr.

Holmes. It wasn’t merely that ghastly face glimmering as white as cheese in the

darkness. It was more subtle than that–something slinking, something furtive,

something guilty– something very unlike the frank, manly lad that I had known. It

left a feeling of horror in my mind.

“But when a man has been soldiering for a year or two

with brother Boer as a playmate, he keeps his nerve and acts quickly. Godfrey had hardly

vanished before I was at the window. There was an awkward catch, and I was some little

time before I could throw it up. Then I nipped through and ran down the garden path in the

direction that I thought he might have taken. “But when a man has been soldiering for a year or two

with brother Boer as a playmate, he keeps his nerve and acts quickly. Godfrey had hardly

vanished before I was at the window. There was an awkward catch, and I was some little

time before I could throw it up. Then I nipped through and ran down the garden path in the

direction that I thought he might have taken.

“It was a long path and the light was not very good, but

it seemed to me something was moving ahead of me. I ran on and called his name, but it was

no use. When I got to the end of the path there were several others branching in different

directions to various outhouses. I stood hesitating, and as I did so I heard distinctly

the sound of a closing door. It was not behind me in the house, but ahead of me, somewhere

in the darkness. That was enough, Mr. Holmes, to assure me that what I had seen was not a

vision. Godfrey had run away from me, and he had shut a door behind him. Of that I was

certain. “It was a long path and the light was not very good, but

it seemed to me something was moving ahead of me. I ran on and called his name, but it was

no use. When I got to the end of the path there were several others branching in different

directions to various outhouses. I stood hesitating, and as I did so I heard distinctly

the sound of a closing door. It was not behind me in the house, but ahead of me, somewhere

in the darkness. That was enough, Mr. Holmes, to assure me that what I had seen was not a

vision. Godfrey had run away from me, and he had shut a door behind him. Of that I was

certain.

“There was nothing more I could do, and I spent an uneasy

night turning the matter over in my mind and trying to find some theory which would cover

the facts. Next day I found the colonel rather more conciliatory, and as his wife remarked

that there were some places of interest in the neighbourhood, it gave me an opening to ask

whether my presence for one more night would incommode them. A somewhat grudging

acquiescence from the old man gave me a clear day in which to make my observations. I was

already perfectly convinced that Godfrey was in hiding somewhere near, but where and why

remained to be solved. “There was nothing more I could do, and I spent an uneasy

night turning the matter over in my mind and trying to find some theory which would cover

the facts. Next day I found the colonel rather more conciliatory, and as his wife remarked

that there were some places of interest in the neighbourhood, it gave me an opening to ask

whether my presence for one more night would incommode them. A somewhat grudging

acquiescence from the old man gave me a clear day in which to make my observations. I was

already perfectly convinced that Godfrey was in hiding somewhere near, but where and why

remained to be solved.

“The house was so large and so rambling that a regiment

might be hid away in it and no one the wiser. If the secret lay there it was difficult for

me to penetrate it. But the door which I had heard close was certainly not in the house. I

must [1005] explore the

garden and see what I could find. There was no difficulty in the way, for the old people

were busy in their own fashion and left me to my own devices. “The house was so large and so rambling that a regiment

might be hid away in it and no one the wiser. If the secret lay there it was difficult for

me to penetrate it. But the door which I had heard close was certainly not in the house. I

must [1005] explore the

garden and see what I could find. There was no difficulty in the way, for the old people

were busy in their own fashion and left me to my own devices.

“There were several small outhouses, but at the end of

the garden there was a detached building of some size–large enough for a

gardener’s or a gamekeeper’s residence. Could this be the place whence the sound

of that shutting door had come? I approached it in a careless fashion as though I were

strolling aimlessly round the grounds. As I did so, a small, brisk, bearded man in a black

coat and bowler hat–not at all the gardener type–came out of the door. To my

surprise, he locked it after him and put the key in his pocket. Then he looked at me with

some surprise on his face. “There were several small outhouses, but at the end of

the garden there was a detached building of some size–large enough for a

gardener’s or a gamekeeper’s residence. Could this be the place whence the sound

of that shutting door had come? I approached it in a careless fashion as though I were

strolling aimlessly round the grounds. As I did so, a small, brisk, bearded man in a black

coat and bowler hat–not at all the gardener type–came out of the door. To my

surprise, he locked it after him and put the key in his pocket. Then he looked at me with

some surprise on his face.

“ ‘Are you a visitor here?’ he asked. “ ‘Are you a visitor here?’ he asked.

“I explained that I was and that I was a friend of

Godfrey’s. “I explained that I was and that I was a friend of

Godfrey’s.

“ ‘What a pity that he should be away on his

travels, for he would have so liked to see me,’ I continued. “ ‘What a pity that he should be away on his

travels, for he would have so liked to see me,’ I continued.

“ ‘Quite so. Exactly,’ said he with a rather

guilty air. ‘No doubt you will renew your visit at some more propitious time.’

He passed on, but when I turned I observed that he was standing watching me,

half-concealed by the laurels at the far end of the garden. “ ‘Quite so. Exactly,’ said he with a rather

guilty air. ‘No doubt you will renew your visit at some more propitious time.’

He passed on, but when I turned I observed that he was standing watching me,

half-concealed by the laurels at the far end of the garden.

“I had a good look at the little house as I passed it,

but the windows were heavily curtained, and, so far as one could see, it was empty. I

might spoil my own game and even be ordered off the premises if I were too audacious, for

I was still conscious that I was being watched. Therefore, I strolled back to the house

and waited for night before I went on with my inquiry. When all was dark and quiet I

slipped out of my window and made my way as silently as possible to the mysterious lodge. “I had a good look at the little house as I passed it,

but the windows were heavily curtained, and, so far as one could see, it was empty. I

might spoil my own game and even be ordered off the premises if I were too audacious, for

I was still conscious that I was being watched. Therefore, I strolled back to the house

and waited for night before I went on with my inquiry. When all was dark and quiet I

slipped out of my window and made my way as silently as possible to the mysterious lodge.

“I have said that it was heavily curtained, but now I

found that the windows were shuttered as well. Some light, however, was breaking through

one of them, so I concentrated my attention upon this. I was in luck, for the curtain had

not been quite closed, and there was a crack in the shutter, so that I could see the

inside of the room. It was a cheery place enough, a bright lamp and a blazing fire.

Opposite to me was seated the little man whom I had seen in the morning. He was smoking a

pipe and reading a paper.” “I have said that it was heavily curtained, but now I

found that the windows were shuttered as well. Some light, however, was breaking through

one of them, so I concentrated my attention upon this. I was in luck, for the curtain had

not been quite closed, and there was a crack in the shutter, so that I could see the

inside of the room. It was a cheery place enough, a bright lamp and a blazing fire.

Opposite to me was seated the little man whom I had seen in the morning. He was smoking a

pipe and reading a paper.”

“What paper?” I asked. “What paper?” I asked.

My client seemed annoyed at the interruption of his narrative. My client seemed annoyed at the interruption of his narrative.

“Can it matter?” he asked. “Can it matter?” he asked.

“It is most essential.” “It is most essential.”

“I really took no notice.” “I really took no notice.”

“Possibly you observed whether it was a broad-leafed

paper or of that smaller type which one associates with weeklies.” “Possibly you observed whether it was a broad-leafed

paper or of that smaller type which one associates with weeklies.”

“Now that you mention it, it was not large. It might have

been the Spectator. However, I had little thought to spare upon such details, for

a second man was seated with his back to the window, and I could swear that this second

man was Godfrey. I could not see his face, but I knew the familiar slope of his shoulders.

He was leaning upon his elbow in an attitude of great melancholy, his body turned towards

the fire. I was hesitating as to what I should do when there was a sharp tap on my

shoulder, and there was Colonel Emsworth beside me. “Now that you mention it, it was not large. It might have

been the Spectator. However, I had little thought to spare upon such details, for

a second man was seated with his back to the window, and I could swear that this second

man was Godfrey. I could not see his face, but I knew the familiar slope of his shoulders.

He was leaning upon his elbow in an attitude of great melancholy, his body turned towards

the fire. I was hesitating as to what I should do when there was a sharp tap on my

shoulder, and there was Colonel Emsworth beside me.

“ ‘This way, sir!’ said he in a low voice. He

walked in silence to the house, and I followed him into my own bedroom. He had picked up a

time-table in the hall. “ ‘This way, sir!’ said he in a low voice. He

walked in silence to the house, and I followed him into my own bedroom. He had picked up a

time-table in the hall.

[1006] “

‘There is a train to London at 8:30,’ said he. ‘The trap will be at the

door at eight.’ [1006] “

‘There is a train to London at 8:30,’ said he. ‘The trap will be at the

door at eight.’

“He was white with rage, and, indeed, I felt myself in so

difficult a position that I could only stammer out a few incoherent apologies in which I

tried to excuse myself by urging my anxiety for my friend. “He was white with rage, and, indeed, I felt myself in so

difficult a position that I could only stammer out a few incoherent apologies in which I

tried to excuse myself by urging my anxiety for my friend.

“ ‘The matter will not bear discussion,’ said

he abruptly. ‘You have made a most damnable intrusion into the privacy of our family.

You were here as a guest and you have become a spy. I have nothing more to say, sir, save

that I have no wish ever to see you again.’ “ ‘The matter will not bear discussion,’ said

he abruptly. ‘You have made a most damnable intrusion into the privacy of our family.

You were here as a guest and you have become a spy. I have nothing more to say, sir, save

that I have no wish ever to see you again.’

“At this I lost my temper, Mr. Holmes, and I spoke with

some warmth. “At this I lost my temper, Mr. Holmes, and I spoke with

some warmth.

“ ‘I have seen your son, and I am convinced that for

some reason of your own you are concealing him from the world. I have no idea what your

motives are in cutting him off in this fashion, but I am sure that he is no longer a free

agent. I warn you, Colonel Emsworth, that until I am assured as to the safety and

well-being of my friend I shall never desist in my efforts to get to the bottom of the

mystery, and I shall certainly not allow myself to be intimidated by anything which you

may say or do.’ “ ‘I have seen your son, and I am convinced that for

some reason of your own you are concealing him from the world. I have no idea what your

motives are in cutting him off in this fashion, but I am sure that he is no longer a free

agent. I warn you, Colonel Emsworth, that until I am assured as to the safety and

well-being of my friend I shall never desist in my efforts to get to the bottom of the

mystery, and I shall certainly not allow myself to be intimidated by anything which you

may say or do.’

“The old fellow looked diabolical, and I really thought

he was about to attack me. I have said that he was a gaunt, fierce old giant, and though I

am no weakling I might have been hard put to it to hold my own against him. However, after

a long glare of rage he turned upon his heel and walked out of the room. For my part, I

took the appointed train in the morning, with the full intention of coming straight to you

and asking for your advice and assistance at the appointment for which I had already

written.” “The old fellow looked diabolical, and I really thought

he was about to attack me. I have said that he was a gaunt, fierce old giant, and though I

am no weakling I might have been hard put to it to hold my own against him. However, after

a long glare of rage he turned upon his heel and walked out of the room. For my part, I

took the appointed train in the morning, with the full intention of coming straight to you

and asking for your advice and assistance at the appointment for which I had already

written.”

Such was the problem which my visitor laid before me. It

presented, as the astute reader will have already perceived, few difficulties in its

solution, for a very limited choice of alternatives must get to the root of the matter.

Still, elementary as it was, there were points of interest and novelty about it which may

excuse my placing it upon record. I now proceeded, using my familiar method of logical

analysis, to narrow down the possible solutions. Such was the problem which my visitor laid before me. It

presented, as the astute reader will have already perceived, few difficulties in its

solution, for a very limited choice of alternatives must get to the root of the matter.

Still, elementary as it was, there were points of interest and novelty about it which may

excuse my placing it upon record. I now proceeded, using my familiar method of logical

analysis, to narrow down the possible solutions.

“The servants,” I asked; “how many were in the

house?” “The servants,” I asked; “how many were in the

house?”

“To the best of my belief there were only the old butler

and his wife. They seemed to live in the simplest fashion.” “To the best of my belief there were only the old butler

and his wife. They seemed to live in the simplest fashion.”

“There was no servant, then, in the detached house?” “There was no servant, then, in the detached house?”

“None, unless the little man with the beard acted as

such. He seemed, however, to be quite a superior person.” “None, unless the little man with the beard acted as

such. He seemed, however, to be quite a superior person.”

“That seems very suggestive. Had you any indication that

food was conveyed from the one house to the other?” “That seems very suggestive. Had you any indication that

food was conveyed from the one house to the other?”

“Now that you mention it, I did see old Ralph carrying a

basket down the garden walk and going in the direction of this house. The idea of food did

not occur to me at the moment.” “Now that you mention it, I did see old Ralph carrying a

basket down the garden walk and going in the direction of this house. The idea of food did

not occur to me at the moment.”

“Did you make any local inquiries?” “Did you make any local inquiries?”

“Yes, I did. I spoke to the station-master and also to

the innkeeper in the village. I simply asked if they knew anything of my old comrade,

Godfrey Emsworth. Both of them assured me that he had gone for a voyage round the world.

He had come home and then had almost at once started off again. The story was evidently

universally accepted.” “Yes, I did. I spoke to the station-master and also to

the innkeeper in the village. I simply asked if they knew anything of my old comrade,

Godfrey Emsworth. Both of them assured me that he had gone for a voyage round the world.

He had come home and then had almost at once started off again. The story was evidently

universally accepted.”

“You said nothing of your suspicions?” “You said nothing of your suspicions?”

“Nothing.” “Nothing.”

[1007] “That

was very wise. The matter should certainly be inquired into. I will go back with you to

Tuxbury Old Park.” [1007] “That

was very wise. The matter should certainly be inquired into. I will go back with you to

Tuxbury Old Park.”

“To-day?” “To-day?”

It happened that at the moment I was clearing up the case

which my friend Watson has described as that of the Abbey School, in which the Duke of

Greyminster was so deeply involved. I had also a commission from the Sultan of Turkey

which called for immediate action, as political consequences of the gravest kind might

arise from its neglect. Therefore it was not until the beginning of the next week, as my

diary records, that I was able to start forth on my mission to Bedfordshire in company

with Mr. James M. Dodd. As we drove to Euston we picked up a grave and taciturn gentleman

of iron-gray aspect, with whom I had made the necessary arrangements. It happened that at the moment I was clearing up the case

which my friend Watson has described as that of the Abbey School, in which the Duke of

Greyminster was so deeply involved. I had also a commission from the Sultan of Turkey

which called for immediate action, as political consequences of the gravest kind might

arise from its neglect. Therefore it was not until the beginning of the next week, as my

diary records, that I was able to start forth on my mission to Bedfordshire in company

with Mr. James M. Dodd. As we drove to Euston we picked up a grave and taciturn gentleman

of iron-gray aspect, with whom I had made the necessary arrangements.

“This is an old friend,” said I to Dodd. “It is

possible that his presence may be entirely unnecessary, and, on the other hand, it may be

essential. It is not necessary at the present stage to go further into the matter.” “This is an old friend,” said I to Dodd. “It is

possible that his presence may be entirely unnecessary, and, on the other hand, it may be

essential. It is not necessary at the present stage to go further into the matter.”

The narratives of Watson have accustomed the reader, no doubt,

to the fact that I do not waste words or disclose my thoughts while a case is actually

under consideration. Dodd seemed surprised, but nothing more was said, and the three of us

continued our journey together. In the train I asked Dodd one more question which I wished

our companion to hear. The narratives of Watson have accustomed the reader, no doubt,

to the fact that I do not waste words or disclose my thoughts while a case is actually

under consideration. Dodd seemed surprised, but nothing more was said, and the three of us

continued our journey together. In the train I asked Dodd one more question which I wished

our companion to hear.

“You say that you saw your friend’s face quite

clearly at the window, so clearly that you are sure of his identity?” “You say that you saw your friend’s face quite

clearly at the window, so clearly that you are sure of his identity?”

“I have no doubt about it whatever. His nose was pressed

against the glass. The lamplight shone full upon him.” “I have no doubt about it whatever. His nose was pressed

against the glass. The lamplight shone full upon him.”

“It could not have been someone resembling him?” “It could not have been someone resembling him?”

“No, no, it was he.” “No, no, it was he.”

“But you say he was changed?” “But you say he was changed?”

“Only in colour. His face was–how shall I describe

it?–it was of a fish-belly whiteness. It was bleached.” “Only in colour. His face was–how shall I describe

it?–it was of a fish-belly whiteness. It was bleached.”

“Was it equally pale all over?” “Was it equally pale all over?”

“I think not. It was his brow which I saw so clearly as

it was pressed against the window.” “I think not. It was his brow which I saw so clearly as

it was pressed against the window.”

“Did you call to him?” “Did you call to him?”

“I was too startled and horrified for the moment. Then I

pursued him, as I have told you, but without result.” “I was too startled and horrified for the moment. Then I

pursued him, as I have told you, but without result.”

My case was practically complete, and there was only one small

incident needed to round it off. When, after a considerable drive, we arrived at the

strange old rambling house which my client had described, it was Ralph, the elderly

butler, who opened the door. I had requisitioned the carriage for the day and had asked my

elderly friend to remain within it unless we should summon him. Ralph, a little wrinkled

old fellow, was in the conventional costume of black coat and pepper-and-salt trousers,

with only one curious variant. He wore brown leather gloves, which at sight of us he

instantly shuffled off, laying them down on the hall-table as we passed in. I have, as my

friend Watson may have remarked, an abnormally acute set of senses, and a faint but

incisive scent was apparent. It seemed to centre on the hall-table. I turned, placed my

hat there, knocked it off, stooped to pick it up, and contrived to bring my nose within a

foot of the gloves. Yes, it was undoubtedly from them that the curious tarry odour was

oozing. I passed on into the study with my case complete. Alas, that I should have to show

my hand so when [1008] I

tell my own story! It was by concealing such links in the chain that Watson was enabled to

produce his meretricious finales. My case was practically complete, and there was only one small

incident needed to round it off. When, after a considerable drive, we arrived at the

strange old rambling house which my client had described, it was Ralph, the elderly

butler, who opened the door. I had requisitioned the carriage for the day and had asked my

elderly friend to remain within it unless we should summon him. Ralph, a little wrinkled

old fellow, was in the conventional costume of black coat and pepper-and-salt trousers,

with only one curious variant. He wore brown leather gloves, which at sight of us he

instantly shuffled off, laying them down on the hall-table as we passed in. I have, as my

friend Watson may have remarked, an abnormally acute set of senses, and a faint but

incisive scent was apparent. It seemed to centre on the hall-table. I turned, placed my

hat there, knocked it off, stooped to pick it up, and contrived to bring my nose within a

foot of the gloves. Yes, it was undoubtedly from them that the curious tarry odour was

oozing. I passed on into the study with my case complete. Alas, that I should have to show

my hand so when [1008] I

tell my own story! It was by concealing such links in the chain that Watson was enabled to

produce his meretricious finales.

Colonel Emsworth was not in his room, but he came quickly

enough on receipt of Ralph’s message. We heard his quick, heavy step in the passage.

The door was flung open and he rushed in with bristling beard and twisted features, as

terrible an old man as ever I have seen. He held our cards in his hand, and he tore them

up and stamped on the fragments. Colonel Emsworth was not in his room, but he came quickly

enough on receipt of Ralph’s message. We heard his quick, heavy step in the passage.

The door was flung open and he rushed in with bristling beard and twisted features, as

terrible an old man as ever I have seen. He held our cards in his hand, and he tore them

up and stamped on the fragments.

“Have I not told you, you infernal busybody, that you are

warned off the premises? Never dare to show your damned face here again. If you enter

again without my leave I shall be within my rights if I use violence. I’ll shoot you,

sir! By God, I will! As to you, sir,” turning upon me, “I extend the same

warning to you. I am familiar with your ignoble profession, but you must take your reputed

talents to some other field. There is no opening for them here.” “Have I not told you, you infernal busybody, that you are

warned off the premises? Never dare to show your damned face here again. If you enter

again without my leave I shall be within my rights if I use violence. I’ll shoot you,

sir! By God, I will! As to you, sir,” turning upon me, “I extend the same

warning to you. I am familiar with your ignoble profession, but you must take your reputed

talents to some other field. There is no opening for them here.”

“I cannot leave here,” said my client firmly,

“until I hear from Godfrey’s own lips that he is under no restraint.” “I cannot leave here,” said my client firmly,

“until I hear from Godfrey’s own lips that he is under no restraint.”

Our involuntary host rang the bell. Our involuntary host rang the bell.

“Ralph,” he said, “telephone down to the county

police and ask the inspector to send up two constables. Tell him there are burglars in the

house.” “Ralph,” he said, “telephone down to the county

police and ask the inspector to send up two constables. Tell him there are burglars in the

house.”

“One moment,” said I. “You must be aware, Mr.

Dodd, that Colonel Emsworth is within his rights and that we have no legal status within

his house. On the other hand, he should recognize that your action is prompted entirely by

solicitude for his son. I venture to hope that if I were allowed to have five

minutes’ conversation with Colonel Emsworth I could certainly alter his view of the

matter.” “One moment,” said I. “You must be aware, Mr.

Dodd, that Colonel Emsworth is within his rights and that we have no legal status within

his house. On the other hand, he should recognize that your action is prompted entirely by

solicitude for his son. I venture to hope that if I were allowed to have five

minutes’ conversation with Colonel Emsworth I could certainly alter his view of the

matter.”

“I am not so easily altered,” said the old soldier.

“Ralph, do what I have told you. What the devil are you waiting for? Ring up the

police!” “I am not so easily altered,” said the old soldier.

“Ralph, do what I have told you. What the devil are you waiting for? Ring up the

police!”

“Nothing of the sort,” I said, putting my back to

the door. “Any police interference would bring about the very catastrophe which you

dread.” I took out my notebook and scribbled one word upon a loose sheet.

“That,” said I as I handed it to Colonel Emsworth, “is what has brought us

here.” “Nothing of the sort,” I said, putting my back to

the door. “Any police interference would bring about the very catastrophe which you

dread.” I took out my notebook and scribbled one word upon a loose sheet.

“That,” said I as I handed it to Colonel Emsworth, “is what has brought us

here.”

He stared at the writing with a face from which every

expression save amazement had vanished. He stared at the writing with a face from which every

expression save amazement had vanished.

“How do you know?” he gasped, sitting down heavily

in his chair. “How do you know?” he gasped, sitting down heavily

in his chair.

“It is my business to know things. That is my

trade.” “It is my business to know things. That is my

trade.”

He sat in deep thought, his gaunt hand tugging at his

straggling beard. Then he made a gesture of resignation. He sat in deep thought, his gaunt hand tugging at his

straggling beard. Then he made a gesture of resignation.

“Well, if you wish to see Godfrey, you shall. It is no

doing of mine, but you have forced my hand. Ralph, tell Mr. Godfrey and Mr. Kent that in

five minutes we shall be with them.” “Well, if you wish to see Godfrey, you shall. It is no

doing of mine, but you have forced my hand. Ralph, tell Mr. Godfrey and Mr. Kent that in

five minutes we shall be with them.”

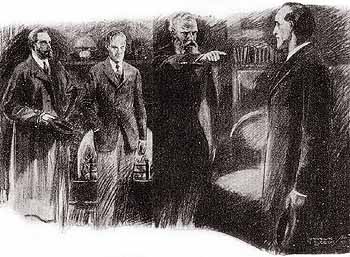

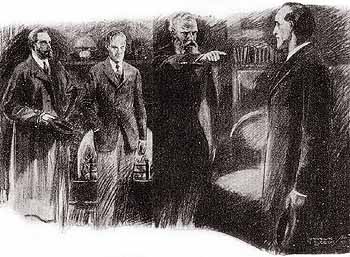

At the end of that time we passed down the garden path and

found ourselves in front of the mystery house at the end. A small bearded man stood at the

door with a look of considerable astonishment upon his face. At the end of that time we passed down the garden path and

found ourselves in front of the mystery house at the end. A small bearded man stood at the

door with a look of considerable astonishment upon his face.

“This is very sudden, Colonel Emsworth,” said he.

“This will disarrange all our plans.” “This is very sudden, Colonel Emsworth,” said he.

“This will disarrange all our plans.”

“I can’t help it, Mr. Kent. Our hands have been

forced. Can Mr. Godfrey see us?” “I can’t help it, Mr. Kent. Our hands have been

forced. Can Mr. Godfrey see us?”

“Yes, he is waiting inside.” He turned and led us

into a large, plainly furnished front room. A man was standing with his back to the fire,

and at the sight of him my client sprang forward with outstretched hand. “Yes, he is waiting inside.” He turned and led us

into a large, plainly furnished front room. A man was standing with his back to the fire,

and at the sight of him my client sprang forward with outstretched hand.

“Why, Godfrey, old man, this is fine!” “Why, Godfrey, old man, this is fine!”

[1009] But

the other waved him back. [1009] But

the other waved him back.

“Don’t touch me, Jimmie. Keep your distance. Yes,

you may well stare! I don’t quite look the smart Lance-Corporal Emsworth, of B

Squadron, do I?” “Don’t touch me, Jimmie. Keep your distance. Yes,

you may well stare! I don’t quite look the smart Lance-Corporal Emsworth, of B

Squadron, do I?”

His appearance was certainly extraordinary. One could see that

he had indeed been a handsome man with clear-cut features sunburned by an African sun, but

mottled in patches over this darker surface were curious whitish patches which had

bleached his skin. His appearance was certainly extraordinary. One could see that

he had indeed been a handsome man with clear-cut features sunburned by an African sun, but

mottled in patches over this darker surface were curious whitish patches which had

bleached his skin.

“That’s why I don’t court visitors,” said

he. “I don’t mind you, Jimmie, but I could have done without your friend. I

suppose there is some good reason for it, but you have me at a disadvantage.” “That’s why I don’t court visitors,” said

he. “I don’t mind you, Jimmie, but I could have done without your friend. I

suppose there is some good reason for it, but you have me at a disadvantage.”

“I wanted to be sure that all was well with you, Godfrey.

I saw you that night when you looked into my window, and I could not let the matter rest

till I had cleared things up.” “I wanted to be sure that all was well with you, Godfrey.

I saw you that night when you looked into my window, and I could not let the matter rest

till I had cleared things up.”

“Old Ralph told me you were there, and I couldn’t

help taking a peep at you. I hoped you would not have seen me, and I had to run to my

burrow when I heard the window go up.” “Old Ralph told me you were there, and I couldn’t

help taking a peep at you. I hoped you would not have seen me, and I had to run to my

burrow when I heard the window go up.”

“But what in heaven’s name is the matter?” “But what in heaven’s name is the matter?”

“Well, it’s not a long story to tell,” said he,

lighting a cigarette. “You remember that morning fight at Buffelsspruit, outside

Pretoria, on the Eastern railway line? You heard I was hit?” “Well, it’s not a long story to tell,” said he,

lighting a cigarette. “You remember that morning fight at Buffelsspruit, outside

Pretoria, on the Eastern railway line? You heard I was hit?”

“Yes, I heard that, but I never got particulars.” “Yes, I heard that, but I never got particulars.”

“Three of us got separated from the others. It was very

broken country, you may remember. There was Simpson–the fellow we called Baldy

Simpson– and Anderson, and I. We were clearing brother Boer, but he lay low and got

the three of us. The other two were killed. I got an elephant bullet through my shoulder.

I stuck on to my horse, however, and he galloped several miles before I fainted and rolled

off the saddle. “Three of us got separated from the others. It was very

broken country, you may remember. There was Simpson–the fellow we called Baldy

Simpson– and Anderson, and I. We were clearing brother Boer, but he lay low and got

the three of us. The other two were killed. I got an elephant bullet through my shoulder.

I stuck on to my horse, however, and he galloped several miles before I fainted and rolled

off the saddle.

“When I came to myself it was nightfall, and I raised

myself up, feeling very weak and ill. To my surprise there was a house close beside me, a

fairly large house with a broad stoep and many windows. It was deadly cold. You remember

the kind of numb cold which used to come at evening, a deadly, sickening sort of cold,

very different from a crisp healthy frost. Well, I was chilled to the bone, and my only

hope seemed to lie in reaching that house. I staggered to my feet and dragged myself

along, hardly conscious of what I did. I have a dim memory of slowly ascending the steps,

entering a wide-opened door, passing into a large room which contained several beds, and

throwing myself down with a gasp of satisfaction upon one of them. It was unmade, but that

troubled me not at all. I drew the clothes over my shivering body and in a moment I was in

a deep sleep. “When I came to myself it was nightfall, and I raised

myself up, feeling very weak and ill. To my surprise there was a house close beside me, a

fairly large house with a broad stoep and many windows. It was deadly cold. You remember

the kind of numb cold which used to come at evening, a deadly, sickening sort of cold,

very different from a crisp healthy frost. Well, I was chilled to the bone, and my only

hope seemed to lie in reaching that house. I staggered to my feet and dragged myself

along, hardly conscious of what I did. I have a dim memory of slowly ascending the steps,

entering a wide-opened door, passing into a large room which contained several beds, and

throwing myself down with a gasp of satisfaction upon one of them. It was unmade, but that

troubled me not at all. I drew the clothes over my shivering body and in a moment I was in

a deep sleep.

“It was morning when I wakened, and it seemed to me that

instead of coming out into a world of sanity I had emerged into some extraordinary

nightmare. The African sun flooded through the big, curtainless windows, and every detail

of the great, bare, whitewashed dormitory stood out hard and clear. In front of me was

standing a small, dwarf-like man with a huge, bulbous head, who was jabbering excitedly in

Dutch, waving two horrible hands which looked to me like brown sponges. Behind him stood a

group of people who seemed to be intensely amused by the situation, but a chill came over

me as I looked at them. Not one of them was a normal human being. Every one was twisted or

swollen or disfigured in some strange way. The laughter of these strange monstrosities was

a dreadful thing to hear. “It was morning when I wakened, and it seemed to me that

instead of coming out into a world of sanity I had emerged into some extraordinary

nightmare. The African sun flooded through the big, curtainless windows, and every detail

of the great, bare, whitewashed dormitory stood out hard and clear. In front of me was

standing a small, dwarf-like man with a huge, bulbous head, who was jabbering excitedly in

Dutch, waving two horrible hands which looked to me like brown sponges. Behind him stood a

group of people who seemed to be intensely amused by the situation, but a chill came over

me as I looked at them. Not one of them was a normal human being. Every one was twisted or

swollen or disfigured in some strange way. The laughter of these strange monstrosities was

a dreadful thing to hear.

[1010] “It

seemed that none of them could speak English, but the situation wanted clearing up, for

the creature with the big head was growing furiously angry, and, uttering wild-beast

cries, he had laid his deformed hands upon me and was dragging me out of bed, regardless

of the fresh flow of blood from my wound. The little monster was as strong as a bull, and

I don’t know what he might have done to me had not an elderly man who was clearly in

authority been attracted to the room by the hubbub. He said a few stern words in Dutch,

and my persecutor shrank away. Then he turned upon me, gazing at me in the utmost

amazement. [1010] “It

seemed that none of them could speak English, but the situation wanted clearing up, for

the creature with the big head was growing furiously angry, and, uttering wild-beast

cries, he had laid his deformed hands upon me and was dragging me out of bed, regardless

of the fresh flow of blood from my wound. The little monster was as strong as a bull, and

I don’t know what he might have done to me had not an elderly man who was clearly in

authority been attracted to the room by the hubbub. He said a few stern words in Dutch,

and my persecutor shrank away. Then he turned upon me, gazing at me in the utmost

amazement.

“ ‘How in the world did you come here?’ he

asked in amazement. ‘Wait a bit! I see that you are tired out and that wounded

shoulder of yours wants looking after. I am a doctor, and I’ll soon have you tied up.

But, man alive! you are in far greater danger here than ever you were on the battlefield.

You are in the Leper Hospital, and you have slept in a leper’s bed.’ “ ‘How in the world did you come here?’ he

asked in amazement. ‘Wait a bit! I see that you are tired out and that wounded

shoulder of yours wants looking after. I am a doctor, and I’ll soon have you tied up.

But, man alive! you are in far greater danger here than ever you were on the battlefield.

You are in the Leper Hospital, and you have slept in a leper’s bed.’

“Need I tell you more, Jimmie? It seems that in view of

the approaching battle all these poor creatures had been evacuated the day before. Then,

as the British advanced, they had been brought back by this, their medical superintendent,

who assured me that, though he believed he was immune to the disease, he would none the

less never have dared to do what I had done. He put me in a private room, treated me

kindly, and within a week or so I was removed to the general hospital at Pretoria. “Need I tell you more, Jimmie? It seems that in view of

the approaching battle all these poor creatures had been evacuated the day before. Then,

as the British advanced, they had been brought back by this, their medical superintendent,

who assured me that, though he believed he was immune to the disease, he would none the

less never have dared to do what I had done. He put me in a private room, treated me

kindly, and within a week or so I was removed to the general hospital at Pretoria.

“So there you have my tragedy. I hoped against hope, but

it was not until I had reached home that the terrible signs which you see upon my face

told me that I had not escaped. What was I to do? I was in this lonely house. We had two

servants whom we could utterly trust. There was a house where I could live. Under pledge

of secrecy, Mr. Kent, who is a surgeon, was prepared to stay with me. It seemed simple

enough on those lines. The alternative was a dreadful one –segregation for life among

strangers with never a hope of release. But absolute secrecy was necessary, or even in

this quiet countryside there would have been an outcry, and I should have been dragged to

my horrible doom. Even you, Jimmie–even you had to be kept in the dark. Why my father

has relented I cannot imagine.” “So there you have my tragedy. I hoped against hope, but

it was not until I had reached home that the terrible signs which you see upon my face

told me that I had not escaped. What was I to do? I was in this lonely house. We had two

servants whom we could utterly trust. There was a house where I could live. Under pledge

of secrecy, Mr. Kent, who is a surgeon, was prepared to stay with me. It seemed simple

enough on those lines. The alternative was a dreadful one –segregation for life among

strangers with never a hope of release. But absolute secrecy was necessary, or even in

this quiet countryside there would have been an outcry, and I should have been dragged to

my horrible doom. Even you, Jimmie–even you had to be kept in the dark. Why my father

has relented I cannot imagine.”

Colonel Emsworth pointed to me. Colonel Emsworth pointed to me.

“This is the gentleman who forced my hand.” He

unfolded the scrap of paper on which I had written the word “Leprosy.” “It

seemed to me that if he knew so much as that it was safer that he should know all.” “This is the gentleman who forced my hand.” He

unfolded the scrap of paper on which I had written the word “Leprosy.” “It

seemed to me that if he knew so much as that it was safer that he should know all.”

“And so it was,” said I. “Who knows but good

may come of it? I understand that only Mr. Kent has seen the patient. May I ask, sir, if

you are an authority on such complaints, which are, I understand, tropical or

semi-tropical in their nature?” “And so it was,” said I. “Who knows but good

may come of it? I understand that only Mr. Kent has seen the patient. May I ask, sir, if

you are an authority on such complaints, which are, I understand, tropical or

semi-tropical in their nature?”

“I have the ordinary knowledge of the educated medical

man,” he observed with some stiffness. “I have the ordinary knowledge of the educated medical

man,” he observed with some stiffness.

“I have no doubt, sir, that you are fully competent, but

I am sure that you will agree that in such a case a second opinion is valuable. You have

avoided this, I understand, for fear that pressure should be put upon you to segregate the

patient.” “I have no doubt, sir, that you are fully competent, but

I am sure that you will agree that in such a case a second opinion is valuable. You have

avoided this, I understand, for fear that pressure should be put upon you to segregate the

patient.”

“That is so,” said Colonel Emsworth. “That is so,” said Colonel Emsworth.

“I foresaw this situation,” I explained, “and I

have brought with me a friend whose discretion may absolutely be trusted. I was able once

to do him a professional service, and he is ready to advise as a friend rather than as a

specialist. His name is Sir James Saunders.” “I foresaw this situation,” I explained, “and I

have brought with me a friend whose discretion may absolutely be trusted. I was able once

to do him a professional service, and he is ready to advise as a friend rather than as a

specialist. His name is Sir James Saunders.”

[1011] The

prospect of an interview with Lord Roberts would not have excited greater wonder and

pleasure in a raw subaltern than was now reflected upon the face of Mr. Kent. [1011] The

prospect of an interview with Lord Roberts would not have excited greater wonder and

pleasure in a raw subaltern than was now reflected upon the face of Mr. Kent.

“I shall indeed be proud,” he murmured. “I shall indeed be proud,” he murmured.

“Then I will ask Sir James to step this way. He is at

present in the carriage outside the door. Meanwhile, Colonel Emsworth, we may perhaps

assemble in your study, where I could give the necessary explanations.” “Then I will ask Sir James to step this way. He is at

present in the carriage outside the door. Meanwhile, Colonel Emsworth, we may perhaps

assemble in your study, where I could give the necessary explanations.”

And here it is that I miss my Watson. By cunning questions and

ejaculations of wonder he could elevate my simple art, which is but systematized common

sense, into a prodigy. When I tell my own story I have no such aid. And yet I will give my

process of thought even as I gave it to my small audience, which included Godfrey’s

mother in the study of Colonel Emsworth. And here it is that I miss my Watson. By cunning questions and

ejaculations of wonder he could elevate my simple art, which is but systematized common

sense, into a prodigy. When I tell my own story I have no such aid. And yet I will give my

process of thought even as I gave it to my small audience, which included Godfrey’s

mother in the study of Colonel Emsworth.

“That process,” said I, “starts upon the

supposition that when you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains,

however improbable, must be the truth. It may well be that several explanations remain, in

which case one tries test after test until one or other of them has a convincing amount of

support. We will now apply this principle to the case in point. As it was first presented

to me, there were three possible explanations of the seclusion or incarceration of this

gentleman in an outhouse of his father’s mansion. There was the explanation that he

was in hiding for a crime, or that he was mad and that they wished to avoid an asylum, or

that he had some disease which caused his segregation. I could think of no other adequate

solutions. These, then, had to be sifted and balanced against each other. “That process,” said I, “starts upon the

supposition that when you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains,

however improbable, must be the truth. It may well be that several explanations remain, in

which case one tries test after test until one or other of them has a convincing amount of

support. We will now apply this principle to the case in point. As it was first presented

to me, there were three possible explanations of the seclusion or incarceration of this

gentleman in an outhouse of his father’s mansion. There was the explanation that he

was in hiding for a crime, or that he was mad and that they wished to avoid an asylum, or

that he had some disease which caused his segregation. I could think of no other adequate

solutions. These, then, had to be sifted and balanced against each other.

“The criminal solution would not bear inspection. No

unsolved crime had been reported from that district. I was sure of that. If it were some

crime not yet discovered, then clearly it would be to the interest of the family to get

rid of the delinquent and send him abroad rather than keep him concealed at home. I could

see no explanation for such a line of conduct. “The criminal solution would not bear inspection. No

unsolved crime had been reported from that district. I was sure of that. If it were some

crime not yet discovered, then clearly it would be to the interest of the family to get

rid of the delinquent and send him abroad rather than keep him concealed at home. I could

see no explanation for such a line of conduct.

“Insanity was more plausible. The presence of the second

person in the outhouse suggested a keeper. The fact that he locked the door when he came

out strengthened the supposition and gave the idea of constraint. On the other hand, this

constraint could not be severe or the young man could not have got loose and come down to

have a look at his friend. You will remember, Mr. Dodd, that I felt round for points,

asking you, for example, about the paper which Mr. Kent was reading. Had it been the Lancet

or the British Medical Journal it would have helped me. It is not illegal,

however, to keep a lunatic upon private premises so long as there is a qualified person in

attendance and that the authorities have been duly notified. Why, then, all this desperate

desire for secrecy? Once again I could not get the theory to fit the facts. “Insanity was more plausible. The presence of the second

person in the outhouse suggested a keeper. The fact that he locked the door when he came

out strengthened the supposition and gave the idea of constraint. On the other hand, this

constraint could not be severe or the young man could not have got loose and come down to

have a look at his friend. You will remember, Mr. Dodd, that I felt round for points,

asking you, for example, about the paper which Mr. Kent was reading. Had it been the Lancet

or the British Medical Journal it would have helped me. It is not illegal,

however, to keep a lunatic upon private premises so long as there is a qualified person in

attendance and that the authorities have been duly notified. Why, then, all this desperate

desire for secrecy? Once again I could not get the theory to fit the facts.

“There remained the third possibility, into which, rare

and unlikely as it was, everything seemed to fit. Leprosy is not uncommon in South Africa.

By some extraordinary chance this youth might have contracted it. His people would be

placed in a very dreadful position, since they would desire to save him from segregation.

Great secrecy would be needed to prevent rumours from getting about and subsequent

interference by the authorities. A devoted medical man, if sufficiently paid, would easily

be found to take charge of the sufferer. There would be no reason why the latter should

not be allowed freedom after dark. Bleaching of the skin is a common result of the

disease. The case was a strong one–so strong that I determined to act as if it were

actually proved. When on arriving here I noticed [1012] that Ralph, who carries out the meals, had gloves

which are impregnated with disinfectants, my last doubts were removed. A single word

showed you, sir, that your secret was discovered, and if I wrote rather than said it, it

was to prove to you that my discretion was to be trusted.” “There remained the third possibility, into which, rare

and unlikely as it was, everything seemed to fit. Leprosy is not uncommon in South Africa.

By some extraordinary chance this youth might have contracted it. His people would be

placed in a very dreadful position, since they would desire to save him from segregation.

Great secrecy would be needed to prevent rumours from getting about and subsequent

interference by the authorities. A devoted medical man, if sufficiently paid, would easily

be found to take charge of the sufferer. There would be no reason why the latter should

not be allowed freedom after dark. Bleaching of the skin is a common result of the

disease. The case was a strong one–so strong that I determined to act as if it were

actually proved. When on arriving here I noticed [1012] that Ralph, who carries out the meals, had gloves

which are impregnated with disinfectants, my last doubts were removed. A single word

showed you, sir, that your secret was discovered, and if I wrote rather than said it, it

was to prove to you that my discretion was to be trusted.”

I was finishing this little analysis of the case when the door

was opened and the austere figure of the great dermatologist was ushered in. But for once

his sphinx-like features had relaxed and there was a warm humanity in his eyes. He strode

up to Colonel Emsworth and shook him by the hand. I was finishing this little analysis of the case when the door

was opened and the austere figure of the great dermatologist was ushered in. But for once

his sphinx-like features had relaxed and there was a warm humanity in his eyes. He strode

up to Colonel Emsworth and shook him by the hand.

“It is often my lot to bring ill-tidings and seldom

good,” said he. “This occasion is the more welcome. It is not leprosy.” “It is often my lot to bring ill-tidings and seldom

good,” said he. “This occasion is the more welcome. It is not leprosy.”

“What?” “What?”

“A well-marked case of pseudo-leprosy or ichthyosis, a

scale-like affection of the skin, unsightly, obstinate, but possibly curable, and

certainly noninfective. Yes, Mr. Holmes, the coincidence is a remarkable one. But is it

coincidence? Are there not subtle forces at work of which we know little? Are we assured

that the apprehension from which this young man has no doubt suffered terribly since his