|

|

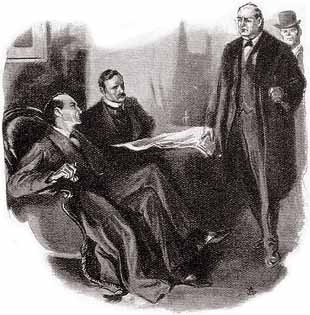

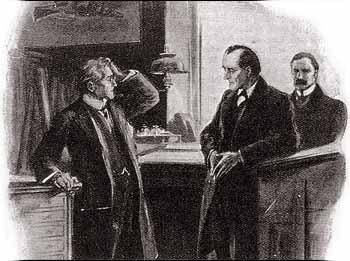

A moment later the tall and portly form of Mycroft Holmes was

ushered into the room. Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth

physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so

masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-gray, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and

so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body

and remembered only the dominant mind. A moment later the tall and portly form of Mycroft Holmes was

ushered into the room. Heavily built and massive, there was a suggestion of uncouth

physical inertia in the figure, but above this unwieldy frame there was perched a head so

masterful in its brow, so alert in its steel-gray, deep-set eyes, so firm in its lips, and

so subtle in its play of expression, that after the first glance one forgot the gross body

and remembered only the dominant mind.

At his heels came our old friend Lestrade, of Scotland

Yard–thin and austere. The gravity of both their faces foretold some weighty quest.

The detective shook hands without a word. Mycroft Holmes struggled out of his overcoat and

subsided into an armchair. At his heels came our old friend Lestrade, of Scotland

Yard–thin and austere. The gravity of both their faces foretold some weighty quest.

The detective shook hands without a word. Mycroft Holmes struggled out of his overcoat and

subsided into an armchair.

“A most annoying business, Sherlock,” said he.

“I extremely dislike altering my habits, but the powers that be would take no denial.

In the present state of Siam it is most awkward that I should be away from the office. But

it is a real crisis. I have never seen the Prime Minister so upset. As to the

Admiralty–it is buzzing like an overturned bee-hive. Have you read up the case?” “A most annoying business, Sherlock,” said he.

“I extremely dislike altering my habits, but the powers that be would take no denial.

In the present state of Siam it is most awkward that I should be away from the office. But

it is a real crisis. I have never seen the Prime Minister so upset. As to the

Admiralty–it is buzzing like an overturned bee-hive. Have you read up the case?”

“We have just done so. What were the technical

papers?” “We have just done so. What were the technical

papers?”

“Ah, there’s the point! Fortunately, it has not come

out. The press would be furious if it did. The papers which this wretched youth had in his

pocket were the plans of the Bruce-Partington submarine.” “Ah, there’s the point! Fortunately, it has not come

out. The press would be furious if it did. The papers which this wretched youth had in his

pocket were the plans of the Bruce-Partington submarine.”

Mycroft Holmes spoke with a solemnity which showed his sense

of the importance of the subject. His brother and I sat expectant. Mycroft Holmes spoke with a solemnity which showed his sense

of the importance of the subject. His brother and I sat expectant.

“Surely you have heard of it? I thought everyone had

heard of it.” “Surely you have heard of it? I thought everyone had

heard of it.”

“Only as a name.” “Only as a name.”

“Its importance can hardly be exaggerated. It has been

the most jealously guarded of all government secrets. You may take it from me that naval

warfare becomes impossible within the radius of a Bruce-Partington’s operation. Two

years ago a very large sum was smuggled through the Estimates and was expended in

acquiring a monopoly of the invention. Every effort has been made to keep the secret. The

plans, which are exceedingly intricate, comprising some thirty separate patents, each

essential to the working of the whole, are kept in an elaborate safe in a confidential

office adjoining the arsenal, with burglar-proof doors and windows. Under no conceivable

circumstances were the plans to be taken from the office. If the chief constructor of the

Navy desired to consult them, even he was forced to go to the Woolwich office for the

purpose. And yet here we find them in the pocket of a dead junior clerk in the heart of

London. From an official point of view it’s simply awful.” “Its importance can hardly be exaggerated. It has been

the most jealously guarded of all government secrets. You may take it from me that naval

warfare becomes impossible within the radius of a Bruce-Partington’s operation. Two

years ago a very large sum was smuggled through the Estimates and was expended in

acquiring a monopoly of the invention. Every effort has been made to keep the secret. The

plans, which are exceedingly intricate, comprising some thirty separate patents, each

essential to the working of the whole, are kept in an elaborate safe in a confidential

office adjoining the arsenal, with burglar-proof doors and windows. Under no conceivable

circumstances were the plans to be taken from the office. If the chief constructor of the

Navy desired to consult them, even he was forced to go to the Woolwich office for the

purpose. And yet here we find them in the pocket of a dead junior clerk in the heart of

London. From an official point of view it’s simply awful.”

“But you have recovered them?” “But you have recovered them?”

“No, Sherlock, no! That’s the pinch. We have not.

Ten papers were taken from Woolwich. There were seven in the pocket of Cadogan West. The

three most essential are gone–stolen, vanished. You must drop everything, Sherlock.

Never mind your usual petty puzzles of the police-court. It’s a vital international

problem [917] that you have

to solve. Why did Cadogan West take the papers, where are the missing ones, how did he

die, how came his body where it was found, how can the evil be set right? Find an answer

to all these questions, and you will have done good service for your country.” “No, Sherlock, no! That’s the pinch. We have not.

Ten papers were taken from Woolwich. There were seven in the pocket of Cadogan West. The

three most essential are gone–stolen, vanished. You must drop everything, Sherlock.

Never mind your usual petty puzzles of the police-court. It’s a vital international

problem [917] that you have

to solve. Why did Cadogan West take the papers, where are the missing ones, how did he

die, how came his body where it was found, how can the evil be set right? Find an answer

to all these questions, and you will have done good service for your country.”

“Why do you not solve it yourself, Mycroft? You can see

as far as I.” “Why do you not solve it yourself, Mycroft? You can see

as far as I.”

“Possibly, Sherlock. But it is a question of getting

details. Give me your details, and from an armchair I will return you an excellent expert

opinion. But to run here and run there, to cross-question railway guards, and lie on my

face with a lens to my eye–it is not my m´┐Żtier. No, you are the one man who

can clear the matter up. If you have a fancy to see your name in the next honours

list– –” “Possibly, Sherlock. But it is a question of getting

details. Give me your details, and from an armchair I will return you an excellent expert

opinion. But to run here and run there, to cross-question railway guards, and lie on my

face with a lens to my eye–it is not my m´┐Żtier. No, you are the one man who

can clear the matter up. If you have a fancy to see your name in the next honours

list– –”

My friend smiled and shook his head. My friend smiled and shook his head.

“I play the game for the game’s own sake,” said

he. “But the problem certainly presents some points of interest, and I shall be very

pleased to look into it. Some more facts, please.” “I play the game for the game’s own sake,” said

he. “But the problem certainly presents some points of interest, and I shall be very

pleased to look into it. Some more facts, please.”

“I have jotted down the more essential ones upon this

sheet of paper, together with a few addresses which you will find of service. The actual

official guardian of the papers is the famous government expert, Sir James Walter, whose

decorations and sub-titles fill two lines of a book of reference. He has grown gray in the

service, is a gentleman, a favoured guest in the most exalted houses, and, above all, a

man whose patriotism is beyond suspicion. He is one of two who have a key of the safe. I

may add that the papers were undoubtedly in the office during working hours on Monday, and

that Sir James left for London about three o’clock taking his key with him. He was at

the house of Admiral Sinclair at Barclay Square during the whole of the evening when this

incident occurred.” “I have jotted down the more essential ones upon this

sheet of paper, together with a few addresses which you will find of service. The actual

official guardian of the papers is the famous government expert, Sir James Walter, whose

decorations and sub-titles fill two lines of a book of reference. He has grown gray in the

service, is a gentleman, a favoured guest in the most exalted houses, and, above all, a

man whose patriotism is beyond suspicion. He is one of two who have a key of the safe. I

may add that the papers were undoubtedly in the office during working hours on Monday, and

that Sir James left for London about three o’clock taking his key with him. He was at

the house of Admiral Sinclair at Barclay Square during the whole of the evening when this

incident occurred.”

“Has the fact been verified?” “Has the fact been verified?”

“Yes; his brother, Colonel Valentine Walter, has

testified to his departure from Woolwich, and Admiral Sinclair to his arrival in London;

so Sir James is no longer a direct factor in the problem.” “Yes; his brother, Colonel Valentine Walter, has

testified to his departure from Woolwich, and Admiral Sinclair to his arrival in London;

so Sir James is no longer a direct factor in the problem.”

“Who was the other man with a key?” “Who was the other man with a key?”

“The senior clerk and draughtsman, Mr. Sidney Johnson. He

is a man of forty, married, with five children. He is a silent, morose man, but he has, on

the whole, an excellent record in the public service. He is unpopular with his colleagues,

but a hard worker. According to his own account, corroborated only by the word of his

wife, he was at home the whole of Monday evening after office hours, and his key has never

left the watch-chain upon which it hangs.” “The senior clerk and draughtsman, Mr. Sidney Johnson. He

is a man of forty, married, with five children. He is a silent, morose man, but he has, on

the whole, an excellent record in the public service. He is unpopular with his colleagues,

but a hard worker. According to his own account, corroborated only by the word of his

wife, he was at home the whole of Monday evening after office hours, and his key has never

left the watch-chain upon which it hangs.”

“Tell us about Cadogan West.” “Tell us about Cadogan West.”

“He has been ten years in the service and has done good

work. He has the reputation of being hot-headed and impetuous, but a straight, honest man.

We have nothing against him. He was next Sidney Johnson in the office. His duties brought

him into daily, personal contact with the plans. No one else had the handling of

them.” “He has been ten years in the service and has done good

work. He has the reputation of being hot-headed and impetuous, but a straight, honest man.

We have nothing against him. He was next Sidney Johnson in the office. His duties brought

him into daily, personal contact with the plans. No one else had the handling of

them.”

“Who locked the plans up that night?” “Who locked the plans up that night?”

“Mr. Sidney Johnson, the senior clerk.” “Mr. Sidney Johnson, the senior clerk.”

“Well, it is surely perfectly clear who took them away.

They are actually found upon the person of this junior clerk, Cadogan West. That seems

final, does it not?” “Well, it is surely perfectly clear who took them away.

They are actually found upon the person of this junior clerk, Cadogan West. That seems

final, does it not?”

“It does, Sherlock, and yet it leaves so much

unexplained. In the first place, why did he take them?” “It does, Sherlock, and yet it leaves so much

unexplained. In the first place, why did he take them?”

“I presume they were of value?” “I presume they were of value?”

“He could have got several thousands for them very

easily.” “He could have got several thousands for them very

easily.”

[918] “Can

you suggest any possible motive for taking the papers to London except to sell them?” [918] “Can

you suggest any possible motive for taking the papers to London except to sell them?”

“No, I cannot.” “No, I cannot.”

“Then we must take that as our working hypothesis. Young

West took the papers. Now this could only be done by having a false key– –” “Then we must take that as our working hypothesis. Young

West took the papers. Now this could only be done by having a false key– –”

“Several false keys. He had to open the building and the

room.” “Several false keys. He had to open the building and the

room.”

“He had, then, several false keys. He took the papers to

London to sell the secret, intending, no doubt, to have the plans themselves back in the

safe next morning before they were missed. While in London on this treasonable mission he

met his end.” “He had, then, several false keys. He took the papers to

London to sell the secret, intending, no doubt, to have the plans themselves back in the

safe next morning before they were missed. While in London on this treasonable mission he

met his end.”

“How?” “How?”

“We will suppose that he was travelling back to Woolwich

when he was killed and thrown out of the compartment.” “We will suppose that he was travelling back to Woolwich

when he was killed and thrown out of the compartment.”

“Aldgate, where the body was found, is considerably past

the station for London Bridge, which would be his route to Woolwich.” “Aldgate, where the body was found, is considerably past

the station for London Bridge, which would be his route to Woolwich.”

“Many circumstances could be imagined under which he

would pass London Bridge. There was someone in the carriage, for example, with whom he was

having an absorbing interview. This interview led to a violent scene in which he lost his

life. Possibly he tried to leave the carriage, fell out on the line, and so met his end.

The other closed the door. There was a thick fog, and nothing could be seen.” “Many circumstances could be imagined under which he

would pass London Bridge. There was someone in the carriage, for example, with whom he was

having an absorbing interview. This interview led to a violent scene in which he lost his

life. Possibly he tried to leave the carriage, fell out on the line, and so met his end.

The other closed the door. There was a thick fog, and nothing could be seen.”

“No better explanation can be given with our present

knowledge; and yet consider, Sherlock, how much you leave untouched. We will suppose, for

argument’s sake, that young Cadogan West had determined to convey these

papers to London. He would naturally have made an appointment with the foreign agent and

kept his evening clear. Instead of that he took two tickets for the theatre, escorted his

fiancee halfway there, and then suddenly disappeared.” “No better explanation can be given with our present

knowledge; and yet consider, Sherlock, how much you leave untouched. We will suppose, for

argument’s sake, that young Cadogan West had determined to convey these

papers to London. He would naturally have made an appointment with the foreign agent and

kept his evening clear. Instead of that he took two tickets for the theatre, escorted his

fiancee halfway there, and then suddenly disappeared.”

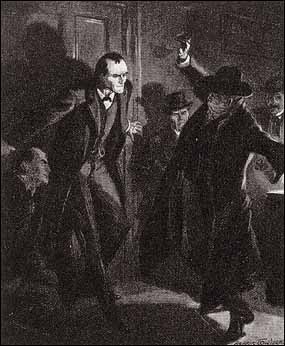

“A blind,” said Lestrade, who had sat listening with

some impatience to the conversation. “A blind,” said Lestrade, who had sat listening with

some impatience to the conversation.

“A very singular one. That is objection No. 1. Objection

No. 2: We will suppose that he reaches London and sees the foreign agent. He must bring

back the papers before morning or the loss will be discovered. He took away ten. Only

seven were in his pocket. What had become of the other three? He certainly would not leave

them of his own free will. Then, again, where is the price of his treason? One would have

expected to find a large sum of money in his pocket.” “A very singular one. That is objection No. 1. Objection

No. 2: We will suppose that he reaches London and sees the foreign agent. He must bring

back the papers before morning or the loss will be discovered. He took away ten. Only

seven were in his pocket. What had become of the other three? He certainly would not leave

them of his own free will. Then, again, where is the price of his treason? One would have

expected to find a large sum of money in his pocket.”

“It seems to me perfectly clear,” said Lestrade.

“I have no doubt at all as to what occurred. He took the papers to sell them. He saw

the agent. They could not agree as to price. He started home again, but the agent went

with him. In the train the agent murdered him, took the more essential papers, and threw

his body from the carriage. That would account for everything, would it not?” “It seems to me perfectly clear,” said Lestrade.

“I have no doubt at all as to what occurred. He took the papers to sell them. He saw

the agent. They could not agree as to price. He started home again, but the agent went

with him. In the train the agent murdered him, took the more essential papers, and threw

his body from the carriage. That would account for everything, would it not?”

“Why had he no ticket?” “Why had he no ticket?”

“The ticket would have shown which station was nearest

the agent’s house. Therefore he took it from the murdered man’s pocket.” “The ticket would have shown which station was nearest

the agent’s house. Therefore he took it from the murdered man’s pocket.”

“Good, Lestrade, very good,” said Holmes. “Your

theory holds together. But if this is true, then the case is at an end. On the one hand,

the traitor is dead. On the other, the plans of the Bruce-Partington submarine are

presumably already on the Continent. What is there for us to do?” “Good, Lestrade, very good,” said Holmes. “Your

theory holds together. But if this is true, then the case is at an end. On the one hand,

the traitor is dead. On the other, the plans of the Bruce-Partington submarine are

presumably already on the Continent. What is there for us to do?”

“To act, Sherlock–to act!” cried Mycroft,

springing to his feet. “All my instincts are against this explanation. Use your

powers! Go to the scene of the crime! See [919]

the people concerned! Leave no stone unturned! In all your career you have

never had so great a chance of serving your country.” “To act, Sherlock–to act!” cried Mycroft,

springing to his feet. “All my instincts are against this explanation. Use your

powers! Go to the scene of the crime! See [919]

the people concerned! Leave no stone unturned! In all your career you have

never had so great a chance of serving your country.”

“Well, well!” said Holmes, shrugging his shoulders.

“Come, Watson! And you, Lestrade, could you favour us with your company for an hour

or two? We will begin our investigation by a visit to Aldgate Station. Good-bye, Mycroft.

I shall let you have a report before evening, but I warn you in advance that you have

little to expect.” “Well, well!” said Holmes, shrugging his shoulders.

“Come, Watson! And you, Lestrade, could you favour us with your company for an hour

or two? We will begin our investigation by a visit to Aldgate Station. Good-bye, Mycroft.

I shall let you have a report before evening, but I warn you in advance that you have

little to expect.”

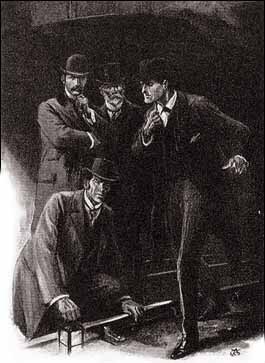

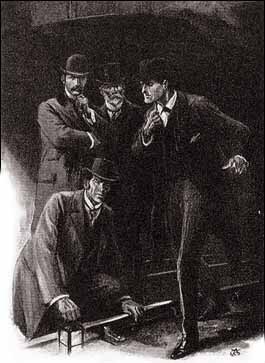

An hour later Holmes, Lestrade and I stood upon the

Underground railroad at the point where it emerges from the tunnel immediately before

Aldgate Station. A courteous red-faced old gentleman represented the railway company. An hour later Holmes, Lestrade and I stood upon the

Underground railroad at the point where it emerges from the tunnel immediately before

Aldgate Station. A courteous red-faced old gentleman represented the railway company.

“This is where the young man’s body lay,” said

he, indicating a spot about three feet from the metals. “It could not have fallen

from above, for these, as you see, are all blank walls. Therefore, it could only have come

from a train, and that train, so far as we can trace it, must have passed about midnight

on Monday.” “This is where the young man’s body lay,” said

he, indicating a spot about three feet from the metals. “It could not have fallen

from above, for these, as you see, are all blank walls. Therefore, it could only have come

from a train, and that train, so far as we can trace it, must have passed about midnight

on Monday.”

“Have the carriages been examined for any sign of

violence?” “Have the carriages been examined for any sign of

violence?”

“There are no such signs, and no ticket has been

found.” “There are no such signs, and no ticket has been

found.”

“No record of a door being found open?” “No record of a door being found open?”

“None.” “None.”

“We have had some fresh evidence this morning,” said

Lestrade. “A passenger who passed Aldgate in an ordinary Metropolitan train about

11:40 on Monday night declares that he heard a heavy thud, as of a body striking the line,

just before the train reached the station. There was dense fog, however, and nothing could

be seen. He made no report of it at the time. Why, whatever is the matter with Mr.

Holmes?” “We have had some fresh evidence this morning,” said

Lestrade. “A passenger who passed Aldgate in an ordinary Metropolitan train about

11:40 on Monday night declares that he heard a heavy thud, as of a body striking the line,

just before the train reached the station. There was dense fog, however, and nothing could

be seen. He made no report of it at the time. Why, whatever is the matter with Mr.

Holmes?”

My friend was standing with an expression of strained

intensity upon his face, staring at the railway metals where they curved out of the

tunnel. Aldgate is a junction, and there was a network of points. On these his eager,

questioning eyes were fixed, and I saw on his keen, alert face that tightening of the

lips, that quiver of the nostrils, and concentration of the heavy, tufted brows which I

knew so well. My friend was standing with an expression of strained

intensity upon his face, staring at the railway metals where they curved out of the

tunnel. Aldgate is a junction, and there was a network of points. On these his eager,

questioning eyes were fixed, and I saw on his keen, alert face that tightening of the

lips, that quiver of the nostrils, and concentration of the heavy, tufted brows which I

knew so well.

“Points,” he muttered; “the points.” “Points,” he muttered; “the points.”

“What of it? What do you mean?” “What of it? What do you mean?”

“I suppose there are no great number of points on a

system such as this?” “I suppose there are no great number of points on a

system such as this?”

“No; there are very few.” “No; there are very few.”

“And a curve, too. Points, and a curve. By Jove! if it

were only so.” “And a curve, too. Points, and a curve. By Jove! if it

were only so.”

“What is it, Mr. Holmes? Have you a clue?” “What is it, Mr. Holmes? Have you a clue?”

“An idea–an indication, no more. But the case

certainly grows in interest. Unique, perfectly unique, and yet why not? I do not see any

indications of bleeding on the line.” “An idea–an indication, no more. But the case

certainly grows in interest. Unique, perfectly unique, and yet why not? I do not see any

indications of bleeding on the line.”

“There were hardly any.” “There were hardly any.”

“But I understand that there was a considerable

wound.” “But I understand that there was a considerable

wound.”

“The bone was crushed, but there was no great external

injury.” “The bone was crushed, but there was no great external

injury.”

“And yet one would have expected some bleeding. Would it

be possible for me to inspect the train which contained the passenger who heard the thud

of a fall in the fog?” “And yet one would have expected some bleeding. Would it

be possible for me to inspect the train which contained the passenger who heard the thud

of a fall in the fog?”

“I fear not, Mr. Holmes. The train has been broken up

before now, and the carriages redistributed.” “I fear not, Mr. Holmes. The train has been broken up

before now, and the carriages redistributed.”

“I can assure you, Mr. Holmes,” said Lestrade,

“that every carriage has been carefully examined. I saw to it myself.” “I can assure you, Mr. Holmes,” said Lestrade,

“that every carriage has been carefully examined. I saw to it myself.”

[920] It

was one of my friend’s most obvious weaknesses that he was impatient with less alert

intelligences than his own. [920] It

was one of my friend’s most obvious weaknesses that he was impatient with less alert

intelligences than his own.

“Very likely,” said he, turning away. “As it

happens, it was not the carriages which I desired to examine. Watson, we have done all we

can here. We need not trouble you any further, Mr. Lestrade. I think our investigations

must now carry us to Woolwich.” “Very likely,” said he, turning away. “As it

happens, it was not the carriages which I desired to examine. Watson, we have done all we

can here. We need not trouble you any further, Mr. Lestrade. I think our investigations

must now carry us to Woolwich.”

At London Bridge, Holmes wrote a telegram to his brother,

which he handed to me before dispatching it. It ran thus: At London Bridge, Holmes wrote a telegram to his brother,

which he handed to me before dispatching it. It ran thus:

See some light in the darkness, but it may possibly flicker

out. Meanwhile, please send by messenger, to await return at Baker Street, a complete list

of all foreign spies or international agents known to be in England, with full address. See some light in the darkness, but it may possibly flicker

out. Meanwhile, please send by messenger, to await return at Baker Street, a complete list

of all foreign spies or international agents known to be in England, with full address.

- SHERLOCK.

“That should be helpful, Watson,” he remarked as

we took our seats in the Woolwich train. “We certainly owe Brother Mycroft a debt for

having introduced us to what promises to be a really very remarkable case.” “That should be helpful, Watson,” he remarked as

we took our seats in the Woolwich train. “We certainly owe Brother Mycroft a debt for

having introduced us to what promises to be a really very remarkable case.”

His eager face still wore that expression of intense and

high-strung energy, which showed me that some novel and suggestive circumstance had opened

up a stimulating line of thought. See the foxhound with hanging ears and drooping tail as

it lolls about the kennels, and compare it with the same hound as, with gleaming eyes and

straining muscles, it runs upon a breast-high scent –such was the change in Holmes

since the morning. He was a different man from the limp and lounging figure in the

mouse-coloured dressing-gown who had prowled so restlessly only a few hours before round

the fog-girt room. His eager face still wore that expression of intense and

high-strung energy, which showed me that some novel and suggestive circumstance had opened

up a stimulating line of thought. See the foxhound with hanging ears and drooping tail as

it lolls about the kennels, and compare it with the same hound as, with gleaming eyes and

straining muscles, it runs upon a breast-high scent –such was the change in Holmes

since the morning. He was a different man from the limp and lounging figure in the

mouse-coloured dressing-gown who had prowled so restlessly only a few hours before round

the fog-girt room.

“There is material here. There is scope,” said he.

“I am dull indeed not to have understood its possibilities.” “There is material here. There is scope,” said he.

“I am dull indeed not to have understood its possibilities.”

“Even now they are dark to me.” “Even now they are dark to me.”

“The end is dark to me also, but I have hold of one idea

which may lead us far. The man met his death elsewhere, and his body was on the roof

of a carriage.” “The end is dark to me also, but I have hold of one idea

which may lead us far. The man met his death elsewhere, and his body was on the roof

of a carriage.”

“On the roof!” “On the roof!”

“Remarkable, is it not? But consider the facts. Is it a

coincidence that it is found at the very point where the train pitches and sways as it

comes round on the points? Is not that the place where an object upon the roof might be

expected to fall off? The points would affect no object inside the train. Either the body

fell from the roof, or a very curious coincidence has occurred. But now consider the

question of the blood. Of course, there was no bleeding on the line if the body had bled

elsewhere. Each fact is suggestive in itself. Together they have a cumulative force.” “Remarkable, is it not? But consider the facts. Is it a

coincidence that it is found at the very point where the train pitches and sways as it

comes round on the points? Is not that the place where an object upon the roof might be

expected to fall off? The points would affect no object inside the train. Either the body

fell from the roof, or a very curious coincidence has occurred. But now consider the

question of the blood. Of course, there was no bleeding on the line if the body had bled

elsewhere. Each fact is suggestive in itself. Together they have a cumulative force.”

“And the ticket, too!” I cried. “And the ticket, too!” I cried.

“Exactly. We could not explain the absence of a ticket.

This would explain it. Everything fits together.” “Exactly. We could not explain the absence of a ticket.

This would explain it. Everything fits together.”

“But suppose it were so, we are still as far as ever from

unravelling the mystery of his death. Indeed, it becomes not simpler but stranger.” “But suppose it were so, we are still as far as ever from

unravelling the mystery of his death. Indeed, it becomes not simpler but stranger.”

“Perhaps,” said Holmes thoughtfully,

“perhaps.” He relapsed into a silent reverie, which lasted until the slow train

drew up at last in Woolwich Station. There he called a cab and drew Mycroft’s paper

from his pocket. “Perhaps,” said Holmes thoughtfully,

“perhaps.” He relapsed into a silent reverie, which lasted until the slow train

drew up at last in Woolwich Station. There he called a cab and drew Mycroft’s paper

from his pocket.

“We have quite a little round of afternoon calls to

make,” said he. “I think that Sir James Walter claims our first attention.” “We have quite a little round of afternoon calls to

make,” said he. “I think that Sir James Walter claims our first attention.”

[921] The

house of the famous official was a fine villa with green lawns stretching down to the

Thames. As we reached it the fog was lifting, and a thin, watery sunshine was breaking

through. A butler answered our ring. [921] The

house of the famous official was a fine villa with green lawns stretching down to the

Thames. As we reached it the fog was lifting, and a thin, watery sunshine was breaking

through. A butler answered our ring.

“Sir James, sir!” said he with solemn face.

“Sir James died this morning.” “Sir James, sir!” said he with solemn face.

“Sir James died this morning.”

“Good heavens!” cried Holmes in amazement. “How

did he die?” “Good heavens!” cried Holmes in amazement. “How

did he die?”

“Perhaps you would care to step in, sir, and see his

brother, Colonel Valentine?” “Perhaps you would care to step in, sir, and see his

brother, Colonel Valentine?”

“Yes, we had best do so.” “Yes, we had best do so.”

We were ushered into a dim-lit drawing-room, where an instant

later we were joined by a very tall, handsome, light-bearded man of fifty, the younger

brother of the dead scientist. His wild eyes, stained cheeks, and unkempt hair all spoke

of the sudden blow which had fallen upon the household. He was hardly articulate as he

spoke of it. We were ushered into a dim-lit drawing-room, where an instant

later we were joined by a very tall, handsome, light-bearded man of fifty, the younger

brother of the dead scientist. His wild eyes, stained cheeks, and unkempt hair all spoke

of the sudden blow which had fallen upon the household. He was hardly articulate as he

spoke of it.

“It was this horrible scandal,” said he. “My

brother, Sir James, was a man of very sensitive honour, and he could not survive such an

affair. It broke his heart. He was always so proud of the efficiency of his department,

and this was a crushing blow.” “It was this horrible scandal,” said he. “My

brother, Sir James, was a man of very sensitive honour, and he could not survive such an

affair. It broke his heart. He was always so proud of the efficiency of his department,

and this was a crushing blow.”

“We had hoped that he might have given us some

indications which would have helped us to clear the matter up.” “We had hoped that he might have given us some

indications which would have helped us to clear the matter up.”

“I assure you that it was all a mystery to him as it is

to you and to all of us. He had already put all his knowledge at the disposal of the

police. Naturally he had no doubt that Cadogan West was guilty. But all the rest was

inconceivable.” “I assure you that it was all a mystery to him as it is

to you and to all of us. He had already put all his knowledge at the disposal of the

police. Naturally he had no doubt that Cadogan West was guilty. But all the rest was

inconceivable.”

“You cannot throw any new light upon the affair?” “You cannot throw any new light upon the affair?”

“I know nothing myself save what I have read or heard. I

have no desire to be discourteous, but you can understand, Mr. Holmes, that we are much

disturbed at present, and I must ask you to hasten this interview to an end.” “I know nothing myself save what I have read or heard. I

have no desire to be discourteous, but you can understand, Mr. Holmes, that we are much

disturbed at present, and I must ask you to hasten this interview to an end.”

“This is indeed an unexpected development,” said my

friend when we had regained the cab. “I wonder if the death was natural, or whether

the poor old fellow killed himself! If the latter, may it be taken as some sign of

self-reproach for duty neglected? We must leave that question to the future. Now we shall

turn to the Cadogan Wests.” “This is indeed an unexpected development,” said my

friend when we had regained the cab. “I wonder if the death was natural, or whether

the poor old fellow killed himself! If the latter, may it be taken as some sign of

self-reproach for duty neglected? We must leave that question to the future. Now we shall

turn to the Cadogan Wests.”

A small but well-kept house in the outskirts of the town

sheltered the bereaved mother. The old lady was too dazed with grief to be of any use to

us, but at her side was a white-faced young lady, who introduced herself as Miss Violet

Westbury, the fiancee of the dead man, and the last to see him upon that fatal night. A small but well-kept house in the outskirts of the town

sheltered the bereaved mother. The old lady was too dazed with grief to be of any use to

us, but at her side was a white-faced young lady, who introduced herself as Miss Violet

Westbury, the fiancee of the dead man, and the last to see him upon that fatal night.

“I cannot explain it, Mr. Holmes,” she said. “I

have not shut an eye since the tragedy, thinking, thinking, thinking, night and day, what

the true meaning of it can be. Arthur was the most single-minded, chivalrous, patriotic

man upon earth. He would have cut his right hand off before he would sell a State secret

confided to his keeping. It is absurd, impossible, preposterous to anyone who knew

him.” “I cannot explain it, Mr. Holmes,” she said. “I

have not shut an eye since the tragedy, thinking, thinking, thinking, night and day, what

the true meaning of it can be. Arthur was the most single-minded, chivalrous, patriotic

man upon earth. He would have cut his right hand off before he would sell a State secret

confided to his keeping. It is absurd, impossible, preposterous to anyone who knew

him.”

“But the facts, Miss Westbury?” “But the facts, Miss Westbury?”

“Yes, yes; I admit I cannot explain them.” “Yes, yes; I admit I cannot explain them.”

“Was he in any want of money?” “Was he in any want of money?”

“No; his needs were very simple and his salary ample. He

had saved a few hundreds, and we were to marry at the New Year.” “No; his needs were very simple and his salary ample. He

had saved a few hundreds, and we were to marry at the New Year.”

“No signs of any mental excitement? Come, Miss Westbury,

be absolutely frank with us.” “No signs of any mental excitement? Come, Miss Westbury,

be absolutely frank with us.”

The quick eye of my companion had noted some change in her

manner. She coloured and hesitated. The quick eye of my companion had noted some change in her

manner. She coloured and hesitated.

“Yes,” she said at last, “I had a feeling that

there was something on his mind.” “Yes,” she said at last, “I had a feeling that

there was something on his mind.”

“For long?” “For long?”

[922] “Only

for the last week or so. He was thoughtful and worried. Once I pressed him about it. He

admitted that there was something, and that it was concerned with his official life.

‘It is too serious for me to speak about, even to you,’ said he. I could get

nothing more.” [922] “Only

for the last week or so. He was thoughtful and worried. Once I pressed him about it. He

admitted that there was something, and that it was concerned with his official life.

‘It is too serious for me to speak about, even to you,’ said he. I could get

nothing more.”

Holmes looked grave. Holmes looked grave.

“Go on, Miss Westbury. Even if it seems to tell against

him, go on. We cannot say what it may lead to.” “Go on, Miss Westbury. Even if it seems to tell against

him, go on. We cannot say what it may lead to.”

“Indeed, I have nothing more to tell. Once or twice it

seemed to me that he was on the point of telling me something. He spoke one evening of the

importance of the secret, and I have some recollection that he said that no doubt foreign

spies would pay a great deal to have it.” “Indeed, I have nothing more to tell. Once or twice it

seemed to me that he was on the point of telling me something. He spoke one evening of the

importance of the secret, and I have some recollection that he said that no doubt foreign

spies would pay a great deal to have it.”

My friend’s face grew graver still. My friend’s face grew graver still.

“Anything else?” “Anything else?”

“He said that we were slack about such matters–that

it would be easy for a traitor to get the plans.” “He said that we were slack about such matters–that

it would be easy for a traitor to get the plans.”

“Was it only recently that he made such remarks?” “Was it only recently that he made such remarks?”

“Yes, quite recently.” “Yes, quite recently.”

“Now tell us of that last evening.” “Now tell us of that last evening.”

“We were to go to the theatre. The fog was so thick that

a cab was useless. We walked, and our way took us close to the office. Suddenly he darted

away into the fog.” “We were to go to the theatre. The fog was so thick that

a cab was useless. We walked, and our way took us close to the office. Suddenly he darted

away into the fog.”

“Without a word?” “Without a word?”

“He gave an exclamation; that was all. I waited but he

never returned. Then I walked home. Next morning, after the office opened, they came to

inquire. About twelve o’clock we heard the terrible news. Oh, Mr. Holmes, if you

could only, only save his honour! It was so much to him.” “He gave an exclamation; that was all. I waited but he

never returned. Then I walked home. Next morning, after the office opened, they came to

inquire. About twelve o’clock we heard the terrible news. Oh, Mr. Holmes, if you

could only, only save his honour! It was so much to him.”

Holmes shook his head sadly. Holmes shook his head sadly.

“Come, Watson,” said he, “our ways lie

elsewhere. Our next station must be the office from which the papers were taken. “Come, Watson,” said he, “our ways lie

elsewhere. Our next station must be the office from which the papers were taken.

“It was black enough before against this young man, but

our inquiries make it blacker,” he remarked as the cab lumbered off. “His coming

marriage gives a motive for the crime. He naturally wanted money. The idea was in his

head, since he spoke about it. He nearly made the girl an accomplice in the treason by

telling her his plans. It is all very bad.” “It was black enough before against this young man, but

our inquiries make it blacker,” he remarked as the cab lumbered off. “His coming

marriage gives a motive for the crime. He naturally wanted money. The idea was in his

head, since he spoke about it. He nearly made the girl an accomplice in the treason by

telling her his plans. It is all very bad.”

“But surely, Holmes, character goes for something? Then,

again, why should he leave the girl in the street and dart away to commit a felony?” “But surely, Holmes, character goes for something? Then,

again, why should he leave the girl in the street and dart away to commit a felony?”

“Exactly! There are certainly objections. But it is a

formidable case which they have to meet.” “Exactly! There are certainly objections. But it is a

formidable case which they have to meet.”

Mr. Sidney Johnson, the senior clerk, met us at the office and

received us with that respect which my companion’s card always commanded. He was a

thin, gruff, bespectacled man of middle age, his cheeks haggard, and his hands twitching

from the nervous strain to which he had been subjected. Mr. Sidney Johnson, the senior clerk, met us at the office and

received us with that respect which my companion’s card always commanded. He was a

thin, gruff, bespectacled man of middle age, his cheeks haggard, and his hands twitching

from the nervous strain to which he had been subjected.

“It is bad, Mr. Holmes, very bad! Have you heard of the

death of the chief?” “It is bad, Mr. Holmes, very bad! Have you heard of the

death of the chief?”

“We have just come from his house.” “We have just come from his house.”

“The place is disorganized. The chief dead, Cadogan West

dead, our papers stolen. And yet, when we closed our door on Monday evening, we were as

efficient an office as any in the government service. Good God, it’s dreadful to

think of! That West, of all men, should have done such a thing!” “The place is disorganized. The chief dead, Cadogan West

dead, our papers stolen. And yet, when we closed our door on Monday evening, we were as

efficient an office as any in the government service. Good God, it’s dreadful to

think of! That West, of all men, should have done such a thing!”

“You are sure of his guilt, then?” “You are sure of his guilt, then?”

[923] “I

can see no other way out of it. And yet I would have trusted him as I trust myself.” [923] “I

can see no other way out of it. And yet I would have trusted him as I trust myself.”

“At what hour was the office closed on Monday?” “At what hour was the office closed on Monday?”

“At five.” “At five.”

“Did you close it?” “Did you close it?”

“I am always the last man out.” “I am always the last man out.”

“Where were the plans?” “Where were the plans?”

“In that safe. I put them there myself.” “In that safe. I put them there myself.”

“Is there no watchman to the building?” “Is there no watchman to the building?”

“There is, but he has other departments to look after as

well. He is an old soldier and a most trustworthy man. He saw nothing that evening. Of

course the fog was very thick.” “There is, but he has other departments to look after as

well. He is an old soldier and a most trustworthy man. He saw nothing that evening. Of

course the fog was very thick.”

“Suppose that Cadogan West wished to make his way into

the building after hours; he would need three keys, would he not, before he could reach

the papers?” “Suppose that Cadogan West wished to make his way into

the building after hours; he would need three keys, would he not, before he could reach

the papers?”

“Yes, he would. The key of the outer door, the key of the

office, and the key of the safe.” “Yes, he would. The key of the outer door, the key of the

office, and the key of the safe.”

“Only Sir James Walter and you had those keys?” “Only Sir James Walter and you had those keys?”

“I had no keys of the doors–only of the safe.” “I had no keys of the doors–only of the safe.”

“Was Sir James a man who was orderly in his habits?” “Was Sir James a man who was orderly in his habits?”

“Yes, I think he was. I know that so far as those three

keys are concerned he kept them on the same ring. I have often seen them there.” “Yes, I think he was. I know that so far as those three

keys are concerned he kept them on the same ring. I have often seen them there.”

“And that ring went with him to London?” “And that ring went with him to London?”

“He said so.” “He said so.”

“And your key never left your possession?” “And your key never left your possession?”

“Never.” “Never.”

“Then West, if he is the culprit, must have had a

duplicate. And yet none was found upon his body. One other point: if a clerk in this

office desired to sell the plans, would it not be simpler to copy the plans for himself

than to take the originals, as was actually done?” “Then West, if he is the culprit, must have had a

duplicate. And yet none was found upon his body. One other point: if a clerk in this

office desired to sell the plans, would it not be simpler to copy the plans for himself

than to take the originals, as was actually done?”

“It would take considerable technical knowledge to copy

the plans in an effective way.” “It would take considerable technical knowledge to copy

the plans in an effective way.”

“But I suppose either Sir James, or you, or West had that

technical knowledge?” “But I suppose either Sir James, or you, or West had that

technical knowledge?”

“No doubt we had, but I beg you won’t try to drag me

into the matter, Mr. Holmes. What is the use of our speculating in this way when the

original plans were actually found on West?” “No doubt we had, but I beg you won’t try to drag me

into the matter, Mr. Holmes. What is the use of our speculating in this way when the

original plans were actually found on West?”

“Well, it is certainly singular that he should run the

risk of taking originals if he could safely have taken copies, which would have equally

served his turn.” “Well, it is certainly singular that he should run the

risk of taking originals if he could safely have taken copies, which would have equally

served his turn.”

“Singular, no doubt–and yet he did so.” “Singular, no doubt–and yet he did so.”

“Every inquiry in this case reveals something

inexplicable. Now there are three papers still missing. They are, as I understand, the

vital ones.” “Every inquiry in this case reveals something

inexplicable. Now there are three papers still missing. They are, as I understand, the

vital ones.”

“Yes, that is so.” “Yes, that is so.”

“Do you mean to say that anyone holding these three

papers, and without the seven others, could construct a Bruce-Partington submarine?” “Do you mean to say that anyone holding these three

papers, and without the seven others, could construct a Bruce-Partington submarine?”

“I reported to that effect to the Admiralty. But to-day I

have been over the drawings again, and I am not so sure of it. The double valves with the

automatic self-adjusting slots are drawn in one of the papers which have been returned.

Until the foreigners had invented that for themselves they could not make the boat. Of

course they might soon get over the difficulty.” “I reported to that effect to the Admiralty. But to-day I

have been over the drawings again, and I am not so sure of it. The double valves with the

automatic self-adjusting slots are drawn in one of the papers which have been returned.

Until the foreigners had invented that for themselves they could not make the boat. Of

course they might soon get over the difficulty.”

“But the three missing drawings are the most

important?” “But the three missing drawings are the most

important?”

[924] “Undoubtedly.” [924] “Undoubtedly.”

“I think, with your permission, I will now take a stroll

round the premises. I do not recall any other question which I desired to ask.” “I think, with your permission, I will now take a stroll

round the premises. I do not recall any other question which I desired to ask.”

He examined the lock of the safe, the door of the room, and

finally the iron shutters of the window. It was only when we were on the lawn outside that

his interest was strongly excited. There was a laurel bush outside the window, and several

of the branches bore signs of having been twisted or snapped. He examined them carefully

with his lens, and then some dim and vague marks upon the earth beneath. Finally he asked

the chief clerk to close the iron shutters, and he pointed out to me that they hardly met

in the centre, and that it would be possible for anyone outside to see what was going on

within the room. He examined the lock of the safe, the door of the room, and

finally the iron shutters of the window. It was only when we were on the lawn outside that

his interest was strongly excited. There was a laurel bush outside the window, and several

of the branches bore signs of having been twisted or snapped. He examined them carefully

with his lens, and then some dim and vague marks upon the earth beneath. Finally he asked

the chief clerk to close the iron shutters, and he pointed out to me that they hardly met

in the centre, and that it would be possible for anyone outside to see what was going on

within the room.

“The indications are ruined by the three days’

delay. They may mean something or nothing. Well, Watson, I do not think that Woolwich can

help us further. It is a small crop which we have gathered. Let us see if we can do better

in London.” “The indications are ruined by the three days’

delay. They may mean something or nothing. Well, Watson, I do not think that Woolwich can

help us further. It is a small crop which we have gathered. Let us see if we can do better

in London.”

Yet we added one more sheaf to our harvest before we left

Woolwich Station. The clerk in the ticket office was able to say with confidence that he

saw Cadogan West–whom he knew well by sight–upon the Monday night, and that he

went to London by the 8:15 to London Bridge. He was alone and took a single third-class

ticket. The clerk was struck at the time by his excited and nervous manner. So shaky was

he that he could hardly pick up his change, and the clerk had helped him with it. A

reference to the timetable showed that the 8:15 was the first train which it was possible

for West to take after he had left the lady about 7:30. Yet we added one more sheaf to our harvest before we left

Woolwich Station. The clerk in the ticket office was able to say with confidence that he

saw Cadogan West–whom he knew well by sight–upon the Monday night, and that he

went to London by the 8:15 to London Bridge. He was alone and took a single third-class

ticket. The clerk was struck at the time by his excited and nervous manner. So shaky was

he that he could hardly pick up his change, and the clerk had helped him with it. A

reference to the timetable showed that the 8:15 was the first train which it was possible

for West to take after he had left the lady about 7:30.

“Let us reconstruct, Watson,” said Holmes after half

an hour of silence. “I am not aware that in all our joint researches we have ever had

a case which was more difficult to get at. Every fresh advance which we make only reveals

a fresh ridge beyond. And yet we have surely made some appreciable progress. “Let us reconstruct, Watson,” said Holmes after half

an hour of silence. “I am not aware that in all our joint researches we have ever had

a case which was more difficult to get at. Every fresh advance which we make only reveals

a fresh ridge beyond. And yet we have surely made some appreciable progress.

“The effect of our inquiries at Woolwich has in the main

been against young Cadogan West; but the indications at the window would lend themselves

to a more favourable hypothesis. Let us suppose, for example, that he had been approached

by some foreign agent. It might have been done under such pledges as would have prevented

him from speaking of it, and yet would have affected his thoughts in the direction

indicated by his remarks to his fiancee. Very good. We will now suppose that as he went to

the theatre with the young lady he suddenly, in the fog, caught a glimpse of this same

agent going in the direction of the office. He was an impetuous man, quick in his

decisions. Everything gave way to his duty. He followed the man, reached the window, saw

the abstraction of the documents, and pursued the thief. In this way we get over the

objection that no one would take originals when he could make copies. This outsider had to

take originals. So far it holds together.” “The effect of our inquiries at Woolwich has in the main

been against young Cadogan West; but the indications at the window would lend themselves

to a more favourable hypothesis. Let us suppose, for example, that he had been approached

by some foreign agent. It might have been done under such pledges as would have prevented

him from speaking of it, and yet would have affected his thoughts in the direction

indicated by his remarks to his fiancee. Very good. We will now suppose that as he went to

the theatre with the young lady he suddenly, in the fog, caught a glimpse of this same

agent going in the direction of the office. He was an impetuous man, quick in his

decisions. Everything gave way to his duty. He followed the man, reached the window, saw

the abstraction of the documents, and pursued the thief. In this way we get over the

objection that no one would take originals when he could make copies. This outsider had to

take originals. So far it holds together.”

“What is the next step?” “What is the next step?”

“Then we come into difficulties. One would imagine that

under such circumstances the first act of young Cadogan West would be to seize the villain

and raise the alarm. Why did he not do so? Could it have been an official superior who

took the papers? That would explain West’s conduct. Or could the chief have given

West the slip in the fog, and West started at once to London to head him off from his own

rooms, presuming that he knew where the rooms were? The call must have been very pressing,

since he left his girl standing in the fog and made no effort to communicate with her. Our

scent runs cold here, and there is a vast gap between either hypothesis and the laying of

West’s body, with seven papers [925] in

his pocket, on the roof of a Metropolitan train. My instinct now is to work from the other

end. If Mycroft has given us the list of addresses we may be able to pick our man and

follow two tracks instead of one.” “Then we come into difficulties. One would imagine that

under such circumstances the first act of young Cadogan West would be to seize the villain

and raise the alarm. Why did he not do so? Could it have been an official superior who

took the papers? That would explain West’s conduct. Or could the chief have given

West the slip in the fog, and West started at once to London to head him off from his own

rooms, presuming that he knew where the rooms were? The call must have been very pressing,

since he left his girl standing in the fog and made no effort to communicate with her. Our

scent runs cold here, and there is a vast gap between either hypothesis and the laying of

West’s body, with seven papers [925] in

his pocket, on the roof of a Metropolitan train. My instinct now is to work from the other

end. If Mycroft has given us the list of addresses we may be able to pick our man and

follow two tracks instead of one.”

Surely enough, a note awaited us at Baker Street. A government

messenger had brought it post-haste. Holmes glanced at it and threw it over to me. Surely enough, a note awaited us at Baker Street. A government

messenger had brought it post-haste. Holmes glanced at it and threw it over to me.

There are numerous small fry, but few who would handle so

big an affair. The only men worth considering are Adolph Meyer, of 13 Great George Street,

Westminster; Louis La Rothiere, of Campden Mansions, Notting Hill; and Hugo Oberstein, 13

Caulfield Gardens, Kensington. The latter was known to be in town on Monday and is now

reported as having left. Glad to hear you have seen some light. The Cabinet awaits your

final report with the utmost anxiety. Urgent representations have arrived from the very

highest quarter. The whole force of the State is at your back if you should need it. There are numerous small fry, but few who would handle so

big an affair. The only men worth considering are Adolph Meyer, of 13 Great George Street,

Westminster; Louis La Rothiere, of Campden Mansions, Notting Hill; and Hugo Oberstein, 13

Caulfield Gardens, Kensington. The latter was known to be in town on Monday and is now

reported as having left. Glad to hear you have seen some light. The Cabinet awaits your

final report with the utmost anxiety. Urgent representations have arrived from the very

highest quarter. The whole force of the State is at your back if you should need it.

- MYCROFT.

“I’m afraid,” said Holmes, smiling,

“that all the queen’s horses and all the queen’s men cannot avail in this

matter.” He had spread out his big map of London and leaned eagerly over it.

“Well, well,” said he presently with an exclamation of satisfaction,

“things are turning a little in our direction at last. Why, Watson, I do honestly

believe that we are going to pull it off, after all.” He slapped me on the shoulder

with a sudden burst of hilarity. “I am going out now. It is only a reconnaissance. I

will do nothing serious without my trusted comrade and biographer at my elbow. Do you stay

here, and the odds are that you will see me again in an hour or two. If time hangs heavy

get foolscap and a pen, and begin your narrative of how we saved the State.” “I’m afraid,” said Holmes, smiling,

“that all the queen’s horses and all the queen’s men cannot avail in this

matter.” He had spread out his big map of London and leaned eagerly over it.

“Well, well,” said he presently with an exclamation of satisfaction,

“things are turning a little in our direction at last. Why, Watson, I do honestly

believe that we are going to pull it off, after all.” He slapped me on the shoulder

with a sudden burst of hilarity. “I am going out now. It is only a reconnaissance. I

will do nothing serious without my trusted comrade and biographer at my elbow. Do you stay

here, and the odds are that you will see me again in an hour or two. If time hangs heavy

get foolscap and a pen, and begin your narrative of how we saved the State.”

I felt some reflection of his elation in my own mind, for I

knew well that he would not depart so far from his usual austerity of demeanour unless

there was good cause for exultation. All the long November evening I waited, filled with

impatience for his return. At last, shortly after nine o’clock, there arrived a

messenger with a note: I felt some reflection of his elation in my own mind, for I

knew well that he would not depart so far from his usual austerity of demeanour unless

there was good cause for exultation. All the long November evening I waited, filled with

impatience for his return. At last, shortly after nine o’clock, there arrived a

messenger with a note:

Am dining at Goldini’s Restaurant, Gloucester Road,

Kensington. Please come at once and join me there. Bring with you a jemmy, a dark lantern,

a chisel, and a revolver. Am dining at Goldini’s Restaurant, Gloucester Road,

Kensington. Please come at once and join me there. Bring with you a jemmy, a dark lantern,

a chisel, and a revolver.

- S. H.

It was a nice equipment for a respectable citizen to carry

through the dim, fog-draped streets. I stowed them all discreetly away in my overcoat and

drove straight to the address given. There sat my friend at a little round table near the

door of the garish Italian restaurant. It was a nice equipment for a respectable citizen to carry

through the dim, fog-draped streets. I stowed them all discreetly away in my overcoat and

drove straight to the address given. There sat my friend at a little round table near the

door of the garish Italian restaurant.

“Have you had something to eat? Then join me in a coffee

and curacao. Try one of the proprietor’s cigars. They are less poisonous than one

would expect. Have you the tools?” “Have you had something to eat? Then join me in a coffee

and curacao. Try one of the proprietor’s cigars. They are less poisonous than one

would expect. Have you the tools?”

“They are here, in my overcoat.” “They are here, in my overcoat.”

“Excellent. Let me give you a short sketch of what I have

done, with some indication of what we are about to do. Now it must be evident to you,

Watson, that this young man’s body was placed on the roof of the train. That

was clear from the instant that I determined the fact that it was from the roof, and not

from a carriage, that he had fallen.” “Excellent. Let me give you a short sketch of what I have

done, with some indication of what we are about to do. Now it must be evident to you,

Watson, that this young man’s body was placed on the roof of the train. That

was clear from the instant that I determined the fact that it was from the roof, and not

from a carriage, that he had fallen.”

“Could it not have been dropped from a bridge?” “Could it not have been dropped from a bridge?”

[926] “I

should say it was impossible. If you examine the roofs you will find that they are

slightly rounded, and there is no railing round them. Therefore, we can say for certain

that young Cadogan West was placed on it.” [926] “I

should say it was impossible. If you examine the roofs you will find that they are

slightly rounded, and there is no railing round them. Therefore, we can say for certain

that young Cadogan West was placed on it.”

“How could he be placed there?” “How could he be placed there?”

“That was the question which we had to answer. There is

only one possible way. You are aware that the Underground runs clear of tunnels at some

points in the West End. I had a vague memory that as I have travelled by it I have

occasionally seen windows just above my head. Now, suppose that a train halted under such

a window, would there be any difficulty in laying a body upon the roof?” “That was the question which we had to answer. There is

only one possible way. You are aware that the Underground runs clear of tunnels at some

points in the West End. I had a vague memory that as I have travelled by it I have

occasionally seen windows just above my head. Now, suppose that a train halted under such

a window, would there be any difficulty in laying a body upon the roof?”

“It seems most improbable.” “It seems most improbable.”

“We must fall back upon the old axiom that when all other

contingencies fail, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Here all

other contingencies have failed. When I found that the leading international agent, who

had just left London, lived in a row of houses which abutted upon the Underground, I was

so pleased that you were a little astonished at my sudden frivolity.” “We must fall back upon the old axiom that when all other

contingencies fail, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Here all

other contingencies have failed. When I found that the leading international agent, who

had just left London, lived in a row of houses which abutted upon the Underground, I was

so pleased that you were a little astonished at my sudden frivolity.”

“Oh, that was it, was it?” “Oh, that was it, was it?”

“Yes, that was it. Mr. Hugo Oberstein, of 13 Caulfield

Gardens, had become my objective. I began my operations at Gloucester Road Station, where

a very helpful official walked with me along the track and allowed me to satisfy myself

not only that the back-stair windows of Caulfield Gardens open on the line but the even

more essential fact that, owing to the intersection of one of the larger railways, the

Underground trains are frequently held motionless for some minutes at that very

spot.” “Yes, that was it. Mr. Hugo Oberstein, of 13 Caulfield

Gardens, had become my objective. I began my operations at Gloucester Road Station, where

a very helpful official walked with me along the track and allowed me to satisfy myself

not only that the back-stair windows of Caulfield Gardens open on the line but the even

more essential fact that, owing to the intersection of one of the larger railways, the

Underground trains are frequently held motionless for some minutes at that very

spot.”

“Splendid, Holmes! You have got it!” “Splendid, Holmes! You have got it!”

“So far–so far, Watson. We advance, but the goal is

afar. Well, having seen the back of Caulfield Gardens, I visited the front and satisfied

myself that the bird was indeed flown. It is a considerable house, unfurnished, so far as

I could judge, in the upper rooms. Oberstein lived there with a single valet, who was

probably a confederate entirely in his confidence. We must bear in mind that Oberstein has

gone to the Continent to dispose of his booty, but not with any idea of flight; for he had

no reason to fear a warrant, and the idea of an amateur domiciliary visit would certainly

never occur to him. Yet that is precisely what we are about to make.” “So far–so far, Watson. We advance, but the goal is

afar. Well, having seen the back of Caulfield Gardens, I visited the front and satisfied

myself that the bird was indeed flown. It is a considerable house, unfurnished, so far as

I could judge, in the upper rooms. Oberstein lived there with a single valet, who was

probably a confederate entirely in his confidence. We must bear in mind that Oberstein has

gone to the Continent to dispose of his booty, but not with any idea of flight; for he had

no reason to fear a warrant, and the idea of an amateur domiciliary visit would certainly

never occur to him. Yet that is precisely what we are about to make.”

“Could we not get a warrant and legalize it?” “Could we not get a warrant and legalize it?”

“Hardly on the evidence.” “Hardly on the evidence.”

“What can we hope to do?” “What can we hope to do?”

“We cannot tell what correspondence may be there.” “We cannot tell what correspondence may be there.”

“I don’t like it, Holmes.” “I don’t like it, Holmes.”

“My dear fellow, you shall keep watch in the street.

I’ll do the criminal part. It’s not a time to stick at trifles. Think of

Mycroft’s note, of the Admiralty, the Cabinet, the exalted person who waits for news.

We are bound to go.” “My dear fellow, you shall keep watch in the street.

I’ll do the criminal part. It’s not a time to stick at trifles. Think of

Mycroft’s note, of the Admiralty, the Cabinet, the exalted person who waits for news.

We are bound to go.”

My answer was to rise from the table. My answer was to rise from the table.

“You are right, Holmes. We are bound to go.” “You are right, Holmes. We are bound to go.”

He sprang up and shook me by the hand. He sprang up and shook me by the hand.

“I knew you would not shrink at the last,” said he,

and for a moment I saw something in his eyes which was nearer to tenderness than I had

ever seen. The next instant he was his masterful, practical self once more. “I knew you would not shrink at the last,” said he,

and for a moment I saw something in his eyes which was nearer to tenderness than I had

ever seen. The next instant he was his masterful, practical self once more.

“It is nearly half a mile, but there is no hurry. Let us

walk,” said he. “Don’t [927]

drop the instruments, I beg. Your arrest as a suspicious character would be

a most unfortunate complication.” “It is nearly half a mile, but there is no hurry. Let us

walk,” said he. “Don’t [927]

drop the instruments, I beg. Your arrest as a suspicious character would be

a most unfortunate complication.”

Caulfield Gardens was one of those lines of flat-faced

pillared, and porticoed houses which are so prominent a product of the middle Victorian

epoch in the West End of London. Next door there appeared to be a children’s party,

for the merry buzz of young voices and the clatter of a piano resounded through the night.

The fog still hung about and screened us with its friendly shade. Holmes had lit his

lantern and flashed it upon the massive door. Caulfield Gardens was one of those lines of flat-faced

pillared, and porticoed houses which are so prominent a product of the middle Victorian

epoch in the West End of London. Next door there appeared to be a children’s party,

for the merry buzz of young voices and the clatter of a piano resounded through the night.

The fog still hung about and screened us with its friendly shade. Holmes had lit his

lantern and flashed it upon the massive door.

“This is a serious proposition,” said he. “It

is certainly bolted as well as locked. We would do better in the area. There is an

excellent archway down yonder in case a too zealous policeman should intrude. Give me a

hand, Watson, and I’ll do the same for you.” “This is a serious proposition,” said he. “It

is certainly bolted as well as locked. We would do better in the area. There is an

excellent archway down yonder in case a too zealous policeman should intrude. Give me a

hand, Watson, and I’ll do the same for you.”

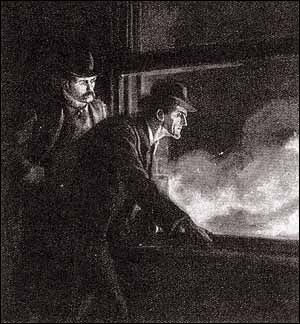

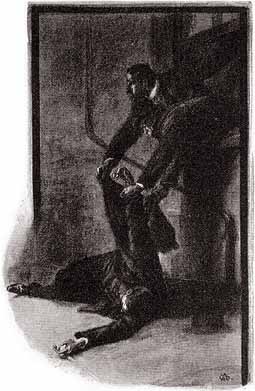

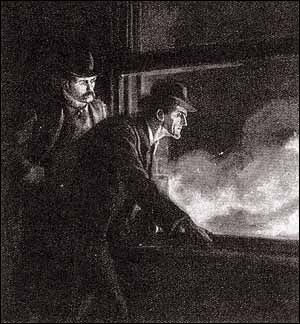

A minute later we were both in the area. Hardly had we reached

the dark shadows before the step of the policeman was heard in the fog above. As its soft

rhythm died away, Holmes set to work upon the lower door. I saw him stoop and strain until

with a sharp crash it flew open. We sprang through into the dark passage, closing the area

door behind us. Holmes led the way up the curving, uncarpeted stair. His little fan of

yellow light shone upon a low window. A minute later we were both in the area. Hardly had we reached

the dark shadows before the step of the policeman was heard in the fog above. As its soft

rhythm died away, Holmes set to work upon the lower door. I saw him stoop and strain until

with a sharp crash it flew open. We sprang through into the dark passage, closing the area

door behind us. Holmes led the way up the curving, uncarpeted stair. His little fan of

yellow light shone upon a low window.

“Here we are, Watson–this must be the one.” He

threw it open, and as he did so there was a low, harsh murmur, growing steadily into a

loud roar as a train dashed past us in the darkness. Holmes swept his light along the

window-sill. It was thickly coated with soot from the passing engines, but the black

surface was blurred and rubbed in places. “Here we are, Watson–this must be the one.” He

threw it open, and as he did so there was a low, harsh murmur, growing steadily into a

loud roar as a train dashed past us in the darkness. Holmes swept his light along the

window-sill. It was thickly coated with soot from the passing engines, but the black

surface was blurred and rubbed in places.

“You can see where they rested the body. Halloa,

Watson! what is this? There can be no doubt that it is a blood mark.” He was pointing

to faint discolourations along the woodwork of the window. “Here it is on the stone

of the stair also. The demonstration is complete. Let us stay here until a train

stops.” “You can see where they rested the body. Halloa,

Watson! what is this? There can be no doubt that it is a blood mark.” He was pointing

to faint discolourations along the woodwork of the window. “Here it is on the stone

of the stair also. The demonstration is complete. Let us stay here until a train

stops.”

We had not long to wait. The very next train roared from the

tunnel as before, but slowed in the open, and then, with a creaking of brakes, pulled up

immediately beneath us. It was not four feet from the window-ledge to the roof of the

carriages. Holmes softly closed the window. We had not long to wait. The very next train roared from the

tunnel as before, but slowed in the open, and then, with a creaking of brakes, pulled up

immediately beneath us. It was not four feet from the window-ledge to the roof of the

carriages. Holmes softly closed the window.

“So far we are justified,” said he. “What do

you think of it, Watson?” “So far we are justified,” said he. “What do

you think of it, Watson?”

“A masterpiece. You have never risen to a greater

height.” “A masterpiece. You have never risen to a greater

height.”

“I cannot agree with you there. From the moment that I

conceived the idea of the body being upon the roof, which surely was not a very abstruse

one, all the rest was inevitable. If it were not for the grave interests involved the

affair up to this point would be insignificant. Our difficulties are still before us. But

perhaps we may find something here which may help us.” “I cannot agree with you there. From the moment that I

conceived the idea of the body being upon the roof, which surely was not a very abstruse

one, all the rest was inevitable. If it were not for the grave interests involved the

affair up to this point would be insignificant. Our difficulties are still before us. But

perhaps we may find something here which may help us.”

We had ascended the kitchen stair and entered the suite of

rooms upon the first floor. One was a dining-room, severely furnished and containing

nothing of interest. A second was a bedroom, which also drew blank. The remaining room

appeared more promising, and my companion settled down to a systematic examination. It was

littered with books and papers, and was evidently used as a study. Swiftly and