|

|

“This matter is very delicate, Mr. Holmes,” he said.

“Consider the relation in which I stand to Professor Presbury both privately and

publicly. I really can hardly justify myself if I speak before any third person.” “This matter is very delicate, Mr. Holmes,” he said.

“Consider the relation in which I stand to Professor Presbury both privately and

publicly. I really can hardly justify myself if I speak before any third person.”

“Have no fear, Mr. Bennett. Dr. Watson is the very soul

of discretion, and I can assure you that this is a matter in which I am very likely to

need an assistant.” “Have no fear, Mr. Bennett. Dr. Watson is the very soul

of discretion, and I can assure you that this is a matter in which I am very likely to

need an assistant.”

“As you like, Mr. Holmes. You will, I am sure, understand

my having some reserves in the matter.” “As you like, Mr. Holmes. You will, I am sure, understand

my having some reserves in the matter.”

“You will appreciate it, Watson, when I tell you that

this gentleman, Mr. Trevor Bennett, is professional assistant to the great scientist,

lives under his roof, and is engaged to his only daughter. Certainly we must agree that

the professor has every claim upon his loyalty and devotion. But it may best be shown by

taking the necessary steps to clear up this strange mystery.” “You will appreciate it, Watson, when I tell you that

this gentleman, Mr. Trevor Bennett, is professional assistant to the great scientist,

lives under his roof, and is engaged to his only daughter. Certainly we must agree that

the professor has every claim upon his loyalty and devotion. But it may best be shown by

taking the necessary steps to clear up this strange mystery.”

“I hope so, Mr. Holmes. That is my one object. Does Dr.

Watson know the situation?” “I hope so, Mr. Holmes. That is my one object. Does Dr.

Watson know the situation?”

“I have not had time to explain it.” “I have not had time to explain it.”

“Then perhaps I had better go over the ground again

before explaining some fresh developments.” “Then perhaps I had better go over the ground again

before explaining some fresh developments.”

“I will do so myself,” said Holmes, “in order

to show that I have the events in their due order. The professor, Watson, is a man of

European reputation. His life has been academic. There has never been a breath of scandal.

He is a widower with one daughter, Edith. He is, I gather, a man of very virile and

positive, one might almost say combative, character. So the matter stood until a very few

months ago. “I will do so myself,” said Holmes, “in order

to show that I have the events in their due order. The professor, Watson, is a man of

European reputation. His life has been academic. There has never been a breath of scandal.

He is a widower with one daughter, Edith. He is, I gather, a man of very virile and

positive, one might almost say combative, character. So the matter stood until a very few

months ago.

“Then the current of his life was broken. He is sixty-one

years of age, but he became engaged to the daughter of Professor Morphy, his colleague in

the chair of comparative anatomy. It was not, as I understand, the reasoned courting of an

elderly man but rather the passionate frenzy of youth, for no one could have shown himself

a more devoted lover. The lady, Alice Morphy, was a very perfect girl both in mind and

body, so that there was every excuse for the professor’s infatuation. None the less,

it did not meet with full approval in his own family.” “Then the current of his life was broken. He is sixty-one

years of age, but he became engaged to the daughter of Professor Morphy, his colleague in

the chair of comparative anatomy. It was not, as I understand, the reasoned courting of an

elderly man but rather the passionate frenzy of youth, for no one could have shown himself

a more devoted lover. The lady, Alice Morphy, was a very perfect girl both in mind and

body, so that there was every excuse for the professor’s infatuation. None the less,

it did not meet with full approval in his own family.”

[1073] “We

thought it rather excessive,” said our visitor. [1073] “We

thought it rather excessive,” said our visitor.

“Exactly. Excessive and a little violent and unnatural.

Professor Presbury was rich, however, and there was no objection upon the part of the

father. The daughter, however, had other views, and there were already several candidates

for her hand, who, if they were less eligible from a worldly point of view, were at least

more of an age. The girl seemed to like the professor in spite of his eccentricities. It

was only age which stood in the way. “Exactly. Excessive and a little violent and unnatural.

Professor Presbury was rich, however, and there was no objection upon the part of the

father. The daughter, however, had other views, and there were already several candidates

for her hand, who, if they were less eligible from a worldly point of view, were at least

more of an age. The girl seemed to like the professor in spite of his eccentricities. It

was only age which stood in the way.

“About this time a little mystery suddenly clouded the

normal routine of the professor’s life. He did what he had never done before. He left

home and gave no indication where he was going. He was away a fortnight and returned

looking rather travel-worn. He made no allusion to where he had been, although he was

usually the frankest of men. It chanced, however, that our client here, Mr. Bennett,

received a letter from a fellow-student in Prague, who said that he was glad to have seen

Professor Presbury there, although he had not been able to talk to him. Only in this way

did his own household learn where he had been. “About this time a little mystery suddenly clouded the

normal routine of the professor’s life. He did what he had never done before. He left

home and gave no indication where he was going. He was away a fortnight and returned

looking rather travel-worn. He made no allusion to where he had been, although he was

usually the frankest of men. It chanced, however, that our client here, Mr. Bennett,

received a letter from a fellow-student in Prague, who said that he was glad to have seen

Professor Presbury there, although he had not been able to talk to him. Only in this way

did his own household learn where he had been.

“Now comes the point. From that time onward a curious

change came over the professor. He became furtive and sly. Those around him had always the

feeling that he was not the man that they had known, but that he was under some shadow

which had darkened his higher qualities. His intellect was not affected. His lectures were

as brilliant as ever. But always there was something new, something sinister and

unexpected. His daughter, who was devoted to him, tried again and again to resume the old

relations and to penetrate this mask which her father seemed to have put on. You, sir, as

I understand, did the same–but all was in vain. And now, Mr. Bennett, tell in your

own words the incident of the letters.” “Now comes the point. From that time onward a curious

change came over the professor. He became furtive and sly. Those around him had always the

feeling that he was not the man that they had known, but that he was under some shadow

which had darkened his higher qualities. His intellect was not affected. His lectures were

as brilliant as ever. But always there was something new, something sinister and

unexpected. His daughter, who was devoted to him, tried again and again to resume the old

relations and to penetrate this mask which her father seemed to have put on. You, sir, as

I understand, did the same–but all was in vain. And now, Mr. Bennett, tell in your

own words the incident of the letters.”

“You must understand, Dr. Watson, that the professor had

no secrets from me. If I were his son or his younger brother I could not have more

completely enjoyed his confidence. As his secretary I handled every paper which came to

him, and I opened and subdivided his letters. Shortly after his return all this was

changed. He told me that certain letters might come to him from London which would be

marked by a cross under the stamp. These were to be set aside for his own eyes only. I may

say that several of these did pass through my hands, that they had the E. C. mark, and

were in an illiterate handwriting. If he answered them at all the answers did not pass

through my hands nor into the letter-basket in which our correspondence was

collected.” “You must understand, Dr. Watson, that the professor had

no secrets from me. If I were his son or his younger brother I could not have more

completely enjoyed his confidence. As his secretary I handled every paper which came to

him, and I opened and subdivided his letters. Shortly after his return all this was

changed. He told me that certain letters might come to him from London which would be

marked by a cross under the stamp. These were to be set aside for his own eyes only. I may

say that several of these did pass through my hands, that they had the E. C. mark, and

were in an illiterate handwriting. If he answered them at all the answers did not pass

through my hands nor into the letter-basket in which our correspondence was

collected.”

“And the box,” said Holmes. “And the box,” said Holmes.

“Ah, yes, the box. The professor brought back a little

wooden box from his travels. It was the one thing which suggested a Continental tour, for

it was one of those quaint carved things which one associates with Germany. This he placed

in his instrument cupboard. One day, in looking for a canula, I took up the box. To my

surprise he was very angry, and reproved me in words which were quite savage for my

curiosity. It was the first time such a thing had happened, and I was deeply hurt. I

endeavoured to explain that it was a mere accident that I had touched the box, but all the

evening I was conscious that he looked at me harshly and that the incident was rankling in

his mind.” Mr. Bennett drew a little diary book from his pocket. “That was on

July 2d,” said he. “Ah, yes, the box. The professor brought back a little

wooden box from his travels. It was the one thing which suggested a Continental tour, for

it was one of those quaint carved things which one associates with Germany. This he placed

in his instrument cupboard. One day, in looking for a canula, I took up the box. To my

surprise he was very angry, and reproved me in words which were quite savage for my

curiosity. It was the first time such a thing had happened, and I was deeply hurt. I

endeavoured to explain that it was a mere accident that I had touched the box, but all the

evening I was conscious that he looked at me harshly and that the incident was rankling in

his mind.” Mr. Bennett drew a little diary book from his pocket. “That was on

July 2d,” said he.

“You are certainly an admirable witness,” said

Holmes. “I may need some of these dates which you have noted.” “You are certainly an admirable witness,” said

Holmes. “I may need some of these dates which you have noted.”

“I learned method among other things from my great

teacher. From the time that I observed abnormality in his behaviour I felt that it was my

duty to study his [1074] case.

Thus I have it here that it was on that very day, July 2d, that Roy attacked the professor

as he came from his study into the hall. Again, on July 11th, there was a scene of the

same sort, and then I have a note of yet another upon July 20th. After that we had to

banish Roy to the stables. He was a dear, affectionate animal–but I fear I weary

you.” “I learned method among other things from my great

teacher. From the time that I observed abnormality in his behaviour I felt that it was my

duty to study his [1074] case.

Thus I have it here that it was on that very day, July 2d, that Roy attacked the professor

as he came from his study into the hall. Again, on July 11th, there was a scene of the

same sort, and then I have a note of yet another upon July 20th. After that we had to

banish Roy to the stables. He was a dear, affectionate animal–but I fear I weary

you.”

Mr. Bennett spoke in a tone of reproach, for it was very clear

that Holmes was not listening. His face was rigid and his eyes gazed abstractedly at the

ceiling. With an effort he recovered himself. Mr. Bennett spoke in a tone of reproach, for it was very clear

that Holmes was not listening. His face was rigid and his eyes gazed abstractedly at the

ceiling. With an effort he recovered himself.

“Singular! Most singular!” he murmured. “These

details were new to me, Mr. Bennett. I think we have now fairly gone over the old ground,

have we not? But you spoke of some fresh developments.” “Singular! Most singular!” he murmured. “These

details were new to me, Mr. Bennett. I think we have now fairly gone over the old ground,

have we not? But you spoke of some fresh developments.”

The pleasant, open face of our visitor clouded over, shadowed

by some grim remembrance. “What I speak of occurred the night before last,” said

he. “I was lying awake about two in the morning, when I was aware of a dull muffled

sound coming from the passage. I opened my door and peeped out. I should explain that the

professor sleeps at the end of the passage– –” The pleasant, open face of our visitor clouded over, shadowed

by some grim remembrance. “What I speak of occurred the night before last,” said

he. “I was lying awake about two in the morning, when I was aware of a dull muffled

sound coming from the passage. I opened my door and peeped out. I should explain that the

professor sleeps at the end of the passage– –”

“The date being– –?” asked Holmes. “The date being– –?” asked Holmes.

Our visitor was clearly annoyed at so irrelevant an

interruption. Our visitor was clearly annoyed at so irrelevant an

interruption.

“I have said, sir, that it was the night before

last–that is, September 4th.” “I have said, sir, that it was the night before

last–that is, September 4th.”

Holmes nodded and smiled. Holmes nodded and smiled.

“Pray continue,” said he. “Pray continue,” said he.

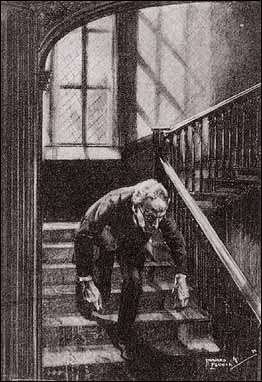

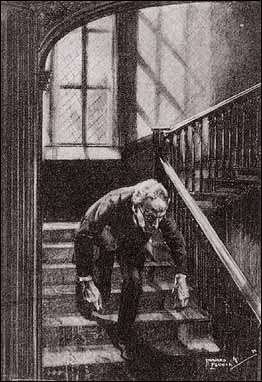

“He sleeps at the end of the passage and would have to

pass my door in order to reach the staircase. It was a really terrifying experience, Mr.

Holmes. I think that I am as strong-nerved as my neighbours, but I was shaken by what I

saw. The passage was dark save that one window halfway along it threw a patch of light. I

could see that something was coming along the passage, something dark and crouching. Then

suddenly it emerged into the light, and I saw that it was he. He was crawling, Mr.

Holmes–crawling! He was not quite on his hands and knees. I should rather say on his

hands and feet, with his face sunk between his hands. Yet he seemed to move with ease. I

was so paralyzed by the sight that it was not until he had reached my door that I was able

to step forward and ask if I could assist him. His answer was extraordinary. He sprang up,

spat out some atrocious word at me, and hurried on past me, and down the staircase. I

waited about for an hour, but he did not come back. It must have been daylight before he

regained his room.” “He sleeps at the end of the passage and would have to

pass my door in order to reach the staircase. It was a really terrifying experience, Mr.

Holmes. I think that I am as strong-nerved as my neighbours, but I was shaken by what I

saw. The passage was dark save that one window halfway along it threw a patch of light. I

could see that something was coming along the passage, something dark and crouching. Then

suddenly it emerged into the light, and I saw that it was he. He was crawling, Mr.

Holmes–crawling! He was not quite on his hands and knees. I should rather say on his

hands and feet, with his face sunk between his hands. Yet he seemed to move with ease. I

was so paralyzed by the sight that it was not until he had reached my door that I was able

to step forward and ask if I could assist him. His answer was extraordinary. He sprang up,

spat out some atrocious word at me, and hurried on past me, and down the staircase. I

waited about for an hour, but he did not come back. It must have been daylight before he

regained his room.”

“Well, Watson, what make you of that?” asked

Holmes with the air of the pathologist who presents a rare specimen. “Well, Watson, what make you of that?” asked

Holmes with the air of the pathologist who presents a rare specimen.

“Lumbago, possibly. I have known a severe attack make a

man walk in just such a way, and nothing would be more trying to the temper.” “Lumbago, possibly. I have known a severe attack make a

man walk in just such a way, and nothing would be more trying to the temper.”

“Good, Watson! You always keep us flat-footed on the

ground. But we can hardly accept lumbago, since he was able to stand erect in a

moment.” “Good, Watson! You always keep us flat-footed on the

ground. But we can hardly accept lumbago, since he was able to stand erect in a

moment.”

“He was never better in health,” said Bennett.

“In fact, he is stronger than I have known him for years. But there are the facts,

Mr. Holmes. It is not a case in which we can consult the police, and yet we are utterly at

our wit’s end as to what to do, and we feel in some strange way that we are drifting

towards disaster. Edith–Miss Presbury–feels as I do, that we cannot wait

passively any longer.” “He was never better in health,” said Bennett.

“In fact, he is stronger than I have known him for years. But there are the facts,

Mr. Holmes. It is not a case in which we can consult the police, and yet we are utterly at

our wit’s end as to what to do, and we feel in some strange way that we are drifting

towards disaster. Edith–Miss Presbury–feels as I do, that we cannot wait

passively any longer.”

“It is certainly a very curious and suggestive case. What

do you think, Watson?” “It is certainly a very curious and suggestive case. What

do you think, Watson?”

“Speaking as a medical man,” said I, “it

appears to be a case for an alienist. The old gentleman’s cerebral processes were

disturbed by the love affair. He made a journey abroad in the hope of breaking himself of

the passion. His letters and the [1075]

box may be connected with some other private transaction–a loan, perhaps, or

share certificates, which are in the box.” “Speaking as a medical man,” said I, “it

appears to be a case for an alienist. The old gentleman’s cerebral processes were

disturbed by the love affair. He made a journey abroad in the hope of breaking himself of

the passion. His letters and the [1075]

box may be connected with some other private transaction–a loan, perhaps, or

share certificates, which are in the box.”

“And the wolfhound no doubt disapproved of the financial

bargain. No, no, Watson, there is more in it than this. Now, I can only suggest–

–” “And the wolfhound no doubt disapproved of the financial

bargain. No, no, Watson, there is more in it than this. Now, I can only suggest–

–”

What Sherlock Holmes was about to suggest will never be known,

for at this moment the door opened and a young lady was shown into the room. As she

appeared Mr. Bennett sprang up with a cry and ran forward with his hands out to meet those

which she had herself outstretched. What Sherlock Holmes was about to suggest will never be known,

for at this moment the door opened and a young lady was shown into the room. As she

appeared Mr. Bennett sprang up with a cry and ran forward with his hands out to meet those

which she had herself outstretched.

“Edith, dear! Nothing the matter, I hope?” “Edith, dear! Nothing the matter, I hope?”

“I felt I must follow you. Oh, Jack, I have been so

dreadfully frightened! It is awful to be there alone.” “I felt I must follow you. Oh, Jack, I have been so

dreadfully frightened! It is awful to be there alone.”

“Mr. Holmes, this is the young lady I spoke of. This is

my fiancee.” “Mr. Holmes, this is the young lady I spoke of. This is

my fiancee.”

“We were gradually coming to that conclusion, were we

not, Watson?” Holmes answered with a smile. “I take it, Miss Presbury, that

there is some fresh development in the case, and that you thought we should know?” “We were gradually coming to that conclusion, were we

not, Watson?” Holmes answered with a smile. “I take it, Miss Presbury, that

there is some fresh development in the case, and that you thought we should know?”

Our new visitor, a bright, handsome girl of a conventional

English type, smiled back at Holmes as she seated herself beside Mr. Bennett. Our new visitor, a bright, handsome girl of a conventional

English type, smiled back at Holmes as she seated herself beside Mr. Bennett.

“When I found Mr. Bennett had left his hotel I thought I

should probably find him here. Of course, he had told me that he would consult you. But,

oh, Mr. Holmes, can you do nothing for my poor father?” “When I found Mr. Bennett had left his hotel I thought I

should probably find him here. Of course, he had told me that he would consult you. But,

oh, Mr. Holmes, can you do nothing for my poor father?”

“I have hopes, Miss Presbury, but the case is still

obscure. Perhaps what you have to say may throw some fresh light upon it.” “I have hopes, Miss Presbury, but the case is still

obscure. Perhaps what you have to say may throw some fresh light upon it.”

“It was last night, Mr. Holmes. He had been very strange

all day. I am sure that there are times when he has no recollection of what he does. He

lives as in a strange dream. Yesterday was such a day. It was not my father with whom I

lived. His outward shell was there, but it was not really he.” “It was last night, Mr. Holmes. He had been very strange

all day. I am sure that there are times when he has no recollection of what he does. He

lives as in a strange dream. Yesterday was such a day. It was not my father with whom I

lived. His outward shell was there, but it was not really he.”

“Tell me what happened.” “Tell me what happened.”

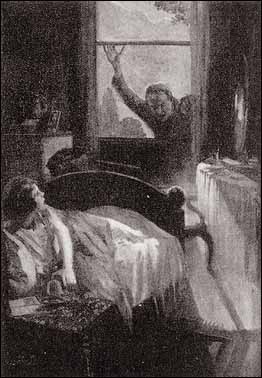

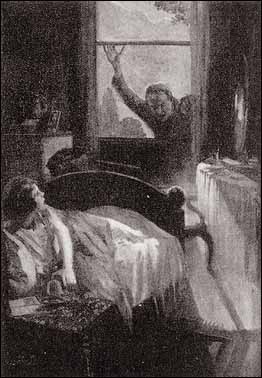

“I was awakened in the night by the dog barking most

furiously. Poor Roy, he is chained now near the stable. I may say that I always sleep with

my door locked; for, as Jack–as Mr. Bennett–will tell you, we all have a feeling

of impending danger. My room is on the second floor. It happened that the blind was up in

my window, and there was bright moonlight outside. As I lay with my eyes fixed upon the

square of light, listening to the frenzied barkings of the dog, I was amazed to see my

father’s face looking in at me. Mr. Holmes, I nearly died of surprise and horror.

There it was pressed against the window-pane, and one hand seemed to be raised as if to

push up the window. If that window had opened, I think I should have gone mad. It was no

delusion, Mr. Holmes. Don’t deceive yourself by thinking so. I dare say it was twenty

seconds or so that I lay paralyzed and watched the face. Then it vanished, but I could

not–I could not spring out of bed and look out after it. I lay cold and shivering

till morning. At breakfast he was sharp and fierce in manner, and made no allusion to the

adventure of the night. Neither did I, but I gave an excuse for coming to town–and

here I am.” “I was awakened in the night by the dog barking most

furiously. Poor Roy, he is chained now near the stable. I may say that I always sleep with

my door locked; for, as Jack–as Mr. Bennett–will tell you, we all have a feeling

of impending danger. My room is on the second floor. It happened that the blind was up in

my window, and there was bright moonlight outside. As I lay with my eyes fixed upon the

square of light, listening to the frenzied barkings of the dog, I was amazed to see my

father’s face looking in at me. Mr. Holmes, I nearly died of surprise and horror.

There it was pressed against the window-pane, and one hand seemed to be raised as if to

push up the window. If that window had opened, I think I should have gone mad. It was no

delusion, Mr. Holmes. Don’t deceive yourself by thinking so. I dare say it was twenty

seconds or so that I lay paralyzed and watched the face. Then it vanished, but I could

not–I could not spring out of bed and look out after it. I lay cold and shivering

till morning. At breakfast he was sharp and fierce in manner, and made no allusion to the

adventure of the night. Neither did I, but I gave an excuse for coming to town–and

here I am.”

Holmes looked thoroughly surprised at Miss Presbury’s

narrative. Holmes looked thoroughly surprised at Miss Presbury’s

narrative.

“My dear young lady, you say that your room is on the

second floor. Is there a long ladder in the garden?” “My dear young lady, you say that your room is on the

second floor. Is there a long ladder in the garden?”

“No, Mr. Holmes, that is the amazing part of it. There is

no possible way of reaching the window–and yet he was there.” “No, Mr. Holmes, that is the amazing part of it. There is

no possible way of reaching the window–and yet he was there.”

“The date being September 5th,” said Holmes.

“That certainly complicates matters.” “The date being September 5th,” said Holmes.

“That certainly complicates matters.”

[1076] It

was the young lady’s turn to look surprised. “This is the second time that you

have alluded to the date, Mr. Holmes,” said Bennett. “Is it possible that it has

any bearing upon the case?” [1076] It

was the young lady’s turn to look surprised. “This is the second time that you

have alluded to the date, Mr. Holmes,” said Bennett. “Is it possible that it has

any bearing upon the case?”

“It is possible–very possible–and yet I have

not my full material at present.” “It is possible–very possible–and yet I have

not my full material at present.”

“Possibly you are thinking of the connection between

insanity and phases of the moon?” “Possibly you are thinking of the connection between

insanity and phases of the moon?”

“No, I assure you. It was quite a different line of

thought. Possibly you can leave your notebook with me, and I will check the dates. Now I

think, Watson, that our line of action is perfectly clear. This young lady has informed

us–and I have the greatest confidence in her intuition–that her father remembers

little or nothing which occurs upon certain dates. We will therefore call upon him as if

he had given us an appointment upon such a date. He will put it down to his own lack of

memory. Thus we will open our campaign by having a good close view of him.” “No, I assure you. It was quite a different line of

thought. Possibly you can leave your notebook with me, and I will check the dates. Now I

think, Watson, that our line of action is perfectly clear. This young lady has informed

us–and I have the greatest confidence in her intuition–that her father remembers

little or nothing which occurs upon certain dates. We will therefore call upon him as if

he had given us an appointment upon such a date. He will put it down to his own lack of

memory. Thus we will open our campaign by having a good close view of him.”

“That is excellent,” said Mr. Bennett. “I warn

you, however, that the professor is irascible and violent at times.” “That is excellent,” said Mr. Bennett. “I warn

you, however, that the professor is irascible and violent at times.”

Holmes smiled. “There are reasons why we should come at

once–very cogent reasons if my theories hold good. To-morrow, Mr. Bennett, will

certainly see us in Camford. There is, if I remember right, an inn called the Chequers

where the port used to be above mediocrity and the linen was above reproach. I think,

Watson, that our lot for the next few days might lie in less pleasant places.” Holmes smiled. “There are reasons why we should come at

once–very cogent reasons if my theories hold good. To-morrow, Mr. Bennett, will

certainly see us in Camford. There is, if I remember right, an inn called the Chequers

where the port used to be above mediocrity and the linen was above reproach. I think,

Watson, that our lot for the next few days might lie in less pleasant places.”

Monday morning found us on our way to the famous university

town–an easy effort on the part of Holmes, who had no roots to pull up, but one which

involved frantic planning and hurrying on my part, as my practice was by this time not

inconsiderable. Holmes made no allusion to the case until after we had deposited our

suitcases at the ancient hostel of which he had spoken. Monday morning found us on our way to the famous university

town–an easy effort on the part of Holmes, who had no roots to pull up, but one which

involved frantic planning and hurrying on my part, as my practice was by this time not

inconsiderable. Holmes made no allusion to the case until after we had deposited our

suitcases at the ancient hostel of which he had spoken.

“I think, Watson, that we can catch the professor just

before lunch. He lectures at eleven and should have an interval at home.” “I think, Watson, that we can catch the professor just

before lunch. He lectures at eleven and should have an interval at home.”

“What possible excuse have we for calling?” “What possible excuse have we for calling?”

Holmes glanced at his notebook. Holmes glanced at his notebook.

“There was a period of excitement upon August 26th. We

will assume that he is a little hazy as to what he does at such times. If we insist that

we are there by appointment I think he will hardly venture to contradict us. Have you the

effrontery necessary to put it through?” “There was a period of excitement upon August 26th. We

will assume that he is a little hazy as to what he does at such times. If we insist that

we are there by appointment I think he will hardly venture to contradict us. Have you the

effrontery necessary to put it through?”

“We can but try.” “We can but try.”

“Excellent, Watson! Compound of the Busy Bee and

Excelsior. We can but try–the motto of the firm. A friendly native will surely guide

us.” “Excellent, Watson! Compound of the Busy Bee and

Excelsior. We can but try–the motto of the firm. A friendly native will surely guide

us.”

Such a one on the back of a smart hansom swept us past a row

of ancient colleges and, finally turning into a tree-lined drive, pulled up at the door of

a charming house, girt round with lawns and covered with purple wisteria. Professor

Presbury was certainly surrounded with every sign not only of comfort but of luxury. Even

as we pulled up, a grizzled head appeared at the front window, and we were aware of a pair

of keen eyes from under shaggy brows which surveyed us through large horn glasses. A

moment later we were actually in his sanctum, and the mysterious scientist, whose vagaries

had brought us from London, was standing before us. There was certainly no sign of

eccentricity either in his manner or appearance, for he was a portly, large-featured man,

grave, tall, and frock-coated, with the dignity of bearing which a lecturer needs. His

eyes were his most remarkable feature, keen, observant, and clever to the verge of

cunning. Such a one on the back of a smart hansom swept us past a row

of ancient colleges and, finally turning into a tree-lined drive, pulled up at the door of

a charming house, girt round with lawns and covered with purple wisteria. Professor

Presbury was certainly surrounded with every sign not only of comfort but of luxury. Even

as we pulled up, a grizzled head appeared at the front window, and we were aware of a pair

of keen eyes from under shaggy brows which surveyed us through large horn glasses. A

moment later we were actually in his sanctum, and the mysterious scientist, whose vagaries

had brought us from London, was standing before us. There was certainly no sign of

eccentricity either in his manner or appearance, for he was a portly, large-featured man,

grave, tall, and frock-coated, with the dignity of bearing which a lecturer needs. His

eyes were his most remarkable feature, keen, observant, and clever to the verge of

cunning.

He looked at our cards. “Pray sit down, gentlemen. What

can I do for you?” He looked at our cards. “Pray sit down, gentlemen. What

can I do for you?”

[1077] Mr.

Holmes smiled amiably. [1077] Mr.

Holmes smiled amiably.

“It was the question which I was about to put to you,

Professor.” “It was the question which I was about to put to you,

Professor.”

“To me, sir!” “To me, sir!”

“Possibly there is some mistake. I heard through a second

person that Professor Presbury of Camford had need of my services.” “Possibly there is some mistake. I heard through a second

person that Professor Presbury of Camford had need of my services.”

“Oh, indeed!” It seemed to me that there was a

malicious sparkle in the intense gray eyes. “You heard that, did you? May I ask the

name of your informant?” “Oh, indeed!” It seemed to me that there was a

malicious sparkle in the intense gray eyes. “You heard that, did you? May I ask the

name of your informant?”

“I am sorry, Professor, but the matter was rather

confidential. If I have made a mistake there is no harm done. I can only express my

regret.” “I am sorry, Professor, but the matter was rather

confidential. If I have made a mistake there is no harm done. I can only express my

regret.”

“Not at all. I should wish to go further into this

matter. It interests me. Have you any scrap of writing, any letter or telegram, to bear

out your assertion?” “Not at all. I should wish to go further into this

matter. It interests me. Have you any scrap of writing, any letter or telegram, to bear

out your assertion?”

“No, I have not.” “No, I have not.”

“I presume that you do not go so far as to assert that I

summoned you?” “I presume that you do not go so far as to assert that I

summoned you?”

“I would rather answer no questions,” said Holmes. “I would rather answer no questions,” said Holmes.

“No, I dare say not,” said the professor with

asperity. “However, that particular one can be answered very easily without your

aid.” “No, I dare say not,” said the professor with

asperity. “However, that particular one can be answered very easily without your

aid.”

He walked across the room to the bell. Our London friend, Mr.

Bennett, answered the call. He walked across the room to the bell. Our London friend, Mr.

Bennett, answered the call.

“Come in, Mr. Bennett. These two gentlemen have come from

London under the impression that they have been summoned. You handle all my

correspondence. Have you a note of anything going to a person named Holmes?” “Come in, Mr. Bennett. These two gentlemen have come from

London under the impression that they have been summoned. You handle all my

correspondence. Have you a note of anything going to a person named Holmes?”

“No, sir,” Bennett answered with a flush. “No, sir,” Bennett answered with a flush.

“That is conclusive,” said the professor, glaring

angrily at my companion. “Now, sir”–he leaned forward with his two hands

upon the table–“it seems to me that your position is a very questionable

one.” “That is conclusive,” said the professor, glaring

angrily at my companion. “Now, sir”–he leaned forward with his two hands

upon the table–“it seems to me that your position is a very questionable

one.”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders. Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“I can only repeat that I am sorry that we have made a

needless intrusion.” “I can only repeat that I am sorry that we have made a

needless intrusion.”

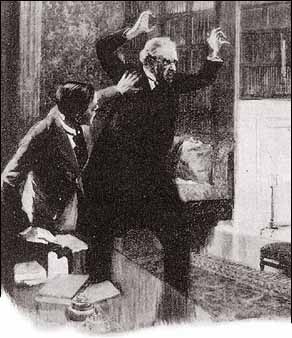

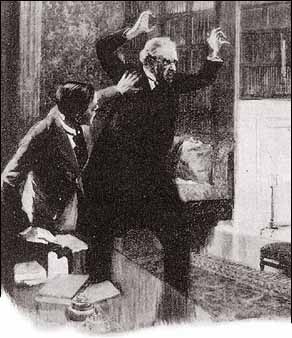

“Hardly enough, Mr. Holmes!” the old man cried in a

high screaming voice, with extraordinary malignancy upon his face. He got between us and

the door as he spoke, and he shook his two hands at us with furious passion. “You can

hardly get out of it so easily as that.” His face was convulsed, and he grinned and

gibbered at us in his senseless rage. I am convinced that we should have had to fight our

way out of the room if Mr. Bennett had not intervened. “Hardly enough, Mr. Holmes!” the old man cried in a

high screaming voice, with extraordinary malignancy upon his face. He got between us and

the door as he spoke, and he shook his two hands at us with furious passion. “You can

hardly get out of it so easily as that.” His face was convulsed, and he grinned and

gibbered at us in his senseless rage. I am convinced that we should have had to fight our

way out of the room if Mr. Bennett had not intervened.

“My dear Professor,” he cried, “consider

your position! Consider the scandal at the university! Mr. Holmes is a well-known man. You

cannot possibly treat him with such discourtesy.” “My dear Professor,” he cried, “consider

your position! Consider the scandal at the university! Mr. Holmes is a well-known man. You

cannot possibly treat him with such discourtesy.”

Sulkily our host–if I may call him so–cleared the

path to the door. We were glad to find ourselves outside the house and in the quiet of the

tree-lined drive. Holmes seemed greatly amused by the episode. Sulkily our host–if I may call him so–cleared the

path to the door. We were glad to find ourselves outside the house and in the quiet of the

tree-lined drive. Holmes seemed greatly amused by the episode.

“Our learned friend’s nerves are somewhat out of

order,” said he. “Perhaps our intrusion was a little crude, and yet we have

gained that personal contact which I desired. But, dear me, Watson, he is surely at our

heels. The villain still pursues us.” “Our learned friend’s nerves are somewhat out of

order,” said he. “Perhaps our intrusion was a little crude, and yet we have

gained that personal contact which I desired. But, dear me, Watson, he is surely at our

heels. The villain still pursues us.”

There were the sounds of running feet behind, but it was, to

my relief, not the formidable professor but his assistant who appeared round the curve of

the drive. He came panting up to us. There were the sounds of running feet behind, but it was, to

my relief, not the formidable professor but his assistant who appeared round the curve of

the drive. He came panting up to us.

“I am so sorry, Mr. Holmes. I wished to apologize.” “I am so sorry, Mr. Holmes. I wished to apologize.”

“My dear sir, there is no need. It is all in the way of

professional experience.” “My dear sir, there is no need. It is all in the way of

professional experience.”

“I have never seen him in a more dangerous mood. But he

grows more sinister. [1078] You

can understand now why his daughter and I are alarmed. And yet his mind is perfectly

clear.” “I have never seen him in a more dangerous mood. But he

grows more sinister. [1078] You

can understand now why his daughter and I are alarmed. And yet his mind is perfectly

clear.”

“Too clear!” said Holmes. “That was my

miscalculation. It is evident that his memory is much more reliable than I had thought. By

the way, can we, before we go, see the window of Miss Presbury’s room?” “Too clear!” said Holmes. “That was my

miscalculation. It is evident that his memory is much more reliable than I had thought. By

the way, can we, before we go, see the window of Miss Presbury’s room?”

Mr. Bennett pushed his way through some shrubs, and we had a

view of the side of the house. Mr. Bennett pushed his way through some shrubs, and we had a

view of the side of the house.

“It is there. The second on the left.” “It is there. The second on the left.”

“Dear me, it seems hardly accessible. And yet you will

observe that there is a creeper below and a water-pipe above which give some

foothold.” “Dear me, it seems hardly accessible. And yet you will

observe that there is a creeper below and a water-pipe above which give some

foothold.”

“I could not climb it myself,” said Mr. Bennett. “I could not climb it myself,” said Mr. Bennett.

“Very likely. It would certainly be a dangerous exploit

for any normal man.” “Very likely. It would certainly be a dangerous exploit

for any normal man.”

“There was one other thing I wish to tell you, Mr.

Holmes. I have the address of the man in London to whom the professor writes. He seems to

have written this morning, and I got it from his blotting-paper. It is an ignoble position

for a trusted secretary, but what else can I do?” “There was one other thing I wish to tell you, Mr.

Holmes. I have the address of the man in London to whom the professor writes. He seems to

have written this morning, and I got it from his blotting-paper. It is an ignoble position

for a trusted secretary, but what else can I do?”

Holmes glanced at the paper and put it into his pocket. Holmes glanced at the paper and put it into his pocket.

“Dorak–a curious name. Slavonic, I imagine. Well, it

is an important link in the chain. We return to London this afternoon, Mr. Bennett. I see

no good purpose to be served by our remaining. We cannot arrest the professor because he

has done no crime, nor can we place him under constraint, for he cannot be proved to be

mad. No action is as yet possible.” “Dorak–a curious name. Slavonic, I imagine. Well, it

is an important link in the chain. We return to London this afternoon, Mr. Bennett. I see

no good purpose to be served by our remaining. We cannot arrest the professor because he

has done no crime, nor can we place him under constraint, for he cannot be proved to be

mad. No action is as yet possible.”

“Then what on earth are we to do?” “Then what on earth are we to do?”

“A little patience, Mr. Bennett. Things will soon

develop. Unless I am mistaken, next Tuesday may mark a crisis. Certainly we shall be in

Camford on that day. Meanwhile, the general position is undeniably unpleasant, and if Miss

Presbury can prolong her visit– –” “A little patience, Mr. Bennett. Things will soon

develop. Unless I am mistaken, next Tuesday may mark a crisis. Certainly we shall be in

Camford on that day. Meanwhile, the general position is undeniably unpleasant, and if Miss

Presbury can prolong her visit– –”

“That is easy.” “That is easy.”

“Then let her stay till we can assure her that all danger

is past. Meanwhile, let him have his way and do not cross him. So long as he is in a good

humour all is well.” “Then let her stay till we can assure her that all danger

is past. Meanwhile, let him have his way and do not cross him. So long as he is in a good

humour all is well.”

“There he is!” said Bennett in a startled whisper.

Looking between the branches we saw the tall, erect figure emerge from the hall door and

look around him. He stood leaning forward, his hands swinging straight before him, his

head turning from side to side. The secretary with a last wave slipped off among the

trees, and we saw him presently rejoin his employer, the two entering the house together

in what seemed to be animated and even excited conversation. “There he is!” said Bennett in a startled whisper.

Looking between the branches we saw the tall, erect figure emerge from the hall door and

look around him. He stood leaning forward, his hands swinging straight before him, his

head turning from side to side. The secretary with a last wave slipped off among the

trees, and we saw him presently rejoin his employer, the two entering the house together

in what seemed to be animated and even excited conversation.

“I expect the old gentleman has been putting two and two

together,” said Holmes as we walked hotelward. “He struck me as having a

particularly clear and logical brain from the little I saw of him. Explosive, no doubt,

but then from his point of view he has something to explode about if detectives are put on

his track and he suspects his own household of doing it. I rather fancy that friend

Bennett is in for an uncomfortable time.” “I expect the old gentleman has been putting two and two

together,” said Holmes as we walked hotelward. “He struck me as having a

particularly clear and logical brain from the little I saw of him. Explosive, no doubt,

but then from his point of view he has something to explode about if detectives are put on

his track and he suspects his own household of doing it. I rather fancy that friend

Bennett is in for an uncomfortable time.”

Holmes stopped at a post-office and sent off a telegram on our

way. The answer reached us in the evening, and he tossed it across to me. Holmes stopped at a post-office and sent off a telegram on our

way. The answer reached us in the evening, and he tossed it across to me.

Have visited the Commercial Road and seen Dorak. Suave

person, Bohemian, elderly. Keeps large general store. Have visited the Commercial Road and seen Dorak. Suave

person, Bohemian, elderly. Keeps large general store.

- MERCER.

[1079]

“Mercer is since your time,” said Holmes. “He is my general utility

man who looks up routine business. It was important to know something of the man with whom

our professor was so secretly corresponding. His nationality connects up with the Prague

visit.” [1079]

“Mercer is since your time,” said Holmes. “He is my general utility

man who looks up routine business. It was important to know something of the man with whom

our professor was so secretly corresponding. His nationality connects up with the Prague

visit.”

“Thank goodness that something connects with

something,” said I. “At present we seem to be faced by a long series of

inexplicable incidents with no bearing upon each other. For example, what possible

connection can there be between an angry wolfhound and a visit to Bohemia, or either of

them with a man crawling down a passage at night? As to your dates, that is the biggest

mystification of all.” “Thank goodness that something connects with

something,” said I. “At present we seem to be faced by a long series of

inexplicable incidents with no bearing upon each other. For example, what possible

connection can there be between an angry wolfhound and a visit to Bohemia, or either of

them with a man crawling down a passage at night? As to your dates, that is the biggest

mystification of all.”

Holmes smiled and rubbed his hands. We were, I may say, seated

in the old sitting-room of the ancient hotel, with a bottle of the famous vintage of which

Holmes had spoken on the table between us. Holmes smiled and rubbed his hands. We were, I may say, seated

in the old sitting-room of the ancient hotel, with a bottle of the famous vintage of which

Holmes had spoken on the table between us.

“Well, now, let us take the dates first,” said he,

his finger-tips together and his manner as if he were addressing a class. “This

excellent young man’s diary shows that there was trouble upon July 2d, and from then

onward it seems to have been at nine-day intervals, with, so far as I remember, only one

exception. Thus the last outbreak upon Friday was on September 3d, which also falls into

the series, as did August 26th, which preceded it. The thing is beyond coincidence.” “Well, now, let us take the dates first,” said he,

his finger-tips together and his manner as if he were addressing a class. “This

excellent young man’s diary shows that there was trouble upon July 2d, and from then

onward it seems to have been at nine-day intervals, with, so far as I remember, only one

exception. Thus the last outbreak upon Friday was on September 3d, which also falls into

the series, as did August 26th, which preceded it. The thing is beyond coincidence.”

I was forced to agree. I was forced to agree.

“Let us, then, form the provisional theory that every

nine days the professor takes some strong drug which has a passing but highly poisonous

effect. His naturally violent nature is intensified by it. He learned to take this drug

while he was in Prague, and is now supplied with it by a Bohemian intermediary in London.

This all hangs together, Watson!” “Let us, then, form the provisional theory that every

nine days the professor takes some strong drug which has a passing but highly poisonous

effect. His naturally violent nature is intensified by it. He learned to take this drug

while he was in Prague, and is now supplied with it by a Bohemian intermediary in London.

This all hangs together, Watson!”

“But the dog, the face at the window, the creeping man in

the passage?” “But the dog, the face at the window, the creeping man in

the passage?”

“Well, well, we have made a beginning. I should not

expect any fresh developments until next Tuesday. In the meantime we can only keep in

touch with friend Bennett and enjoy the amenities of this charming town.” “Well, well, we have made a beginning. I should not

expect any fresh developments until next Tuesday. In the meantime we can only keep in

touch with friend Bennett and enjoy the amenities of this charming town.”

In the morning Mr. Bennett slipped round to bring us the

latest report. As Holmes had imagined, times had not been easy with him. Without exactly

accusing him of being responsible for our presence, the professor had been very rough and

rude in his speech, and evidently felt some strong grievance. This morning he was quite

himself again, however, and had delivered his usual brilliant lecture to a crowded class.

“Apart from his queer fits,” said Bennett, “he has actually more energy and

vitality than I can ever remember, nor was his brain ever clearer. But it’s not

he–it’s never the man whom we have known.” In the morning Mr. Bennett slipped round to bring us the

latest report. As Holmes had imagined, times had not been easy with him. Without exactly

accusing him of being responsible for our presence, the professor had been very rough and

rude in his speech, and evidently felt some strong grievance. This morning he was quite

himself again, however, and had delivered his usual brilliant lecture to a crowded class.

“Apart from his queer fits,” said Bennett, “he has actually more energy and

vitality than I can ever remember, nor was his brain ever clearer. But it’s not

he–it’s never the man whom we have known.”

“I don’t think you have anything to fear now for a

week at least,” Holmes answered. “I am a busy man, and Dr. Watson has his

patients to attend to. Let us agree that we meet here at this hour next Tuesday, and I

shall be surprised if before we leave you again we are not able to explain, even if we

cannot perhaps put an end to, your troubles. Meanwhile, keep us posted in what

occurs.” “I don’t think you have anything to fear now for a

week at least,” Holmes answered. “I am a busy man, and Dr. Watson has his

patients to attend to. Let us agree that we meet here at this hour next Tuesday, and I

shall be surprised if before we leave you again we are not able to explain, even if we

cannot perhaps put an end to, your troubles. Meanwhile, keep us posted in what

occurs.”

I saw nothing of my friend for the next few days, but on the

following Monday evening I had a short note asking me to meet him next day at the train.

From what he told me as we travelled up to Camford all was well, the peace of the

professor’s house had been unruffled, and his own conduct perfectly normal. This also

was the report which was given us by Mr. Bennett himself when he called upon us that

evening at our old quarters in the Chequers. “He heard from his London correspondent

to-day. There was a letter and there was a small packet, [1080] each with the cross under the stamp which warned me

not to touch them. There has been nothing else.” I saw nothing of my friend for the next few days, but on the

following Monday evening I had a short note asking me to meet him next day at the train.

From what he told me as we travelled up to Camford all was well, the peace of the

professor’s house had been unruffled, and his own conduct perfectly normal. This also

was the report which was given us by Mr. Bennett himself when he called upon us that

evening at our old quarters in the Chequers. “He heard from his London correspondent

to-day. There was a letter and there was a small packet, [1080] each with the cross under the stamp which warned me

not to touch them. There has been nothing else.”

“That may prove quite enough,” said Holmes grimly.

“Now, Mr. Bennett, we shall, I think, come to some conclusion to-night. If my

deductions are correct we should have an opportunity of bringing matters to a head. In

order to do so it is necessary to hold the professor under observation. I would suggest,

therefore, that you remain awake and on the lookout. Should you hear him pass your door,

do not interrupt him, but follow him as discreetly as you can. Dr. Watson and I will not

be far off. By the way, where is the key of that little box of which you spoke?” “That may prove quite enough,” said Holmes grimly.

“Now, Mr. Bennett, we shall, I think, come to some conclusion to-night. If my

deductions are correct we should have an opportunity of bringing matters to a head. In

order to do so it is necessary to hold the professor under observation. I would suggest,

therefore, that you remain awake and on the lookout. Should you hear him pass your door,

do not interrupt him, but follow him as discreetly as you can. Dr. Watson and I will not

be far off. By the way, where is the key of that little box of which you spoke?”

“Upon his watch-chain.” “Upon his watch-chain.”

“I fancy our researches must lie in that direction. At

the worst the lock should not be very formidable. Have you any other able-bodied man on

the premises?” “I fancy our researches must lie in that direction. At

the worst the lock should not be very formidable. Have you any other able-bodied man on

the premises?”

“There is the coachman, Macphail.” “There is the coachman, Macphail.”

“Where does he sleep?” “Where does he sleep?”

“Over the stables.” “Over the stables.”

“We might possibly want him. Well, we can do no more

until we see how things develop. Good-bye–but I expect that we shall see you before

morning.” “We might possibly want him. Well, we can do no more

until we see how things develop. Good-bye–but I expect that we shall see you before

morning.”

It was nearly midnight before we took our station among some

bushes immediately opposite the hall door of the professor. It was a fine night, but

chilly, and we were glad of our warm overcoats. There was a breeze, and clouds were

scudding across the sky, obscuring from time to time the half-moon. It would have been a

dismal vigil were it not for the expectation and excitement which carried us along, and

the assurance of my comrade that we had probably reached the end of the strange sequence

of events which had engaged our attention. It was nearly midnight before we took our station among some

bushes immediately opposite the hall door of the professor. It was a fine night, but

chilly, and we were glad of our warm overcoats. There was a breeze, and clouds were

scudding across the sky, obscuring from time to time the half-moon. It would have been a

dismal vigil were it not for the expectation and excitement which carried us along, and

the assurance of my comrade that we had probably reached the end of the strange sequence

of events which had engaged our attention.

“If the cycle of nine days holds good then we shall have

the professor at his worst to-night,” said Holmes. “The fact that these strange

symptoms began after his visit to Prague, that he is in secret correspondence with a

Bohemian dealer in London, who presumably represents someone in Prague, and that he

received a packet from him this very day, all point in one direction. What he takes and

why he takes it are still beyond our ken, but that it emanates in some way from Prague is

clear enough. He takes it under definite directions which regulate this ninth-day system,

which was the first point which attracted my attention. But his symptoms are most

remarkable. Did you observe his knuckles?” “If the cycle of nine days holds good then we shall have

the professor at his worst to-night,” said Holmes. “The fact that these strange

symptoms began after his visit to Prague, that he is in secret correspondence with a

Bohemian dealer in London, who presumably represents someone in Prague, and that he

received a packet from him this very day, all point in one direction. What he takes and

why he takes it are still beyond our ken, but that it emanates in some way from Prague is

clear enough. He takes it under definite directions which regulate this ninth-day system,

which was the first point which attracted my attention. But his symptoms are most

remarkable. Did you observe his knuckles?”

I had to confess that I did not. I had to confess that I did not.

“Thick and horny in a way which is quite new in my

experience. Always look at the hands first, Watson. Then cuffs, trouser-knees, and boots.

Very curious knuckles which can only be explained by the mode of progression observed

by– –” Holmes paused and suddenly clapped his hand to his forehead.

“Oh, Watson, Watson, what a fool I have been! It seems incredible, and yet it must be

true. All points in one direction. How could I miss seeing the connection of ideas? Those

knuckles–how could I have passed those knuckles? And the dog! And the ivy! It’s

surely time that I disappeared into that little farm of my dreams. Look out, Watson! Here

he is! We shall have the chance of seeing for ourselves.” “Thick and horny in a way which is quite new in my

experience. Always look at the hands first, Watson. Then cuffs, trouser-knees, and boots.

Very curious knuckles which can only be explained by the mode of progression observed

by– –” Holmes paused and suddenly clapped his hand to his forehead.

“Oh, Watson, Watson, what a fool I have been! It seems incredible, and yet it must be

true. All points in one direction. How could I miss seeing the connection of ideas? Those

knuckles–how could I have passed those knuckles? And the dog! And the ivy! It’s

surely time that I disappeared into that little farm of my dreams. Look out, Watson! Here

he is! We shall have the chance of seeing for ourselves.”

The hall door had slowly opened, and against the lamplit

background we saw the tall figure of Professor Presbury. He was clad in his dressing-gown.

As he stood outlined in the doorway he was erect but leaning forward with dangling arms,

as when we saw him last. The hall door had slowly opened, and against the lamplit

background we saw the tall figure of Professor Presbury. He was clad in his dressing-gown.

As he stood outlined in the doorway he was erect but leaning forward with dangling arms,

as when we saw him last.

Now he stepped forward into the drive, and an extraordinary

change came over him. He sank down into a crouching position and moved along upon his

hands [1081] and feet,

skipping every now and then as if he were overflowing with energy and vitality. He moved

along the face of the house and then round the corner. As he disappeared Bennett slipped

through the hall door and softly followed him. Now he stepped forward into the drive, and an extraordinary

change came over him. He sank down into a crouching position and moved along upon his

hands [1081] and feet,

skipping every now and then as if he were overflowing with energy and vitality. He moved

along the face of the house and then round the corner. As he disappeared Bennett slipped

through the hall door and softly followed him.

“Come, Watson, come!” cried Holmes, and we stole as

softly as we could through the bushes until we had gained a spot whence we could see the

other side of the house, which was bathed in the light of the half-moon. The professor was

clearly visible crouching at the foot of the ivy-covered wall. As we watched him he

suddenly began with incredible agility to ascend it. From branch to branch he sprang, sure

of foot and firm of grasp, climbing apparently in mere joy at his own powers, with no

definite object in view. With his dressing-gown flapping on each side of him, he looked

like some huge bat glued against the side of his own house, a great square dark patch upon

the moonlit wall. Presently he tired of this amusement, and, dropping from branch to

branch, he squatted down into the old attitude and moved towards the stables, creeping

along in the same strange way as before. The wolfhound was out now, barking furiously, and

more excited than ever when it actually caught sight of its master. It was straining on

its chain and quivering with eagerness and rage. The professor squatted down very

deliberately just out of reach of the hound and began to provoke it in every possible way.

He took handfuls of pebbles from the drive and threw them in the dog’s face, prodded

him with a stick which he had picked up, flicked his hands about only a few inches from

the gaping mouth, and endeavoured in every way to increase the animal’s fury, which

was already beyond all control. In all our adventures I do not know that I have ever seen

a more strange sight than this impassive and still dignified figure crouching frog-like

upon the ground and goading to a wilder exhibition of passion the maddened hound, which

ramped and raged in front of him, by all manner of ingenious and calculated cruelty. “Come, Watson, come!” cried Holmes, and we stole as

softly as we could through the bushes until we had gained a spot whence we could see the

other side of the house, which was bathed in the light of the half-moon. The professor was

clearly visible crouching at the foot of the ivy-covered wall. As we watched him he

suddenly began with incredible agility to ascend it. From branch to branch he sprang, sure

of foot and firm of grasp, climbing apparently in mere joy at his own powers, with no

definite object in view. With his dressing-gown flapping on each side of him, he looked

like some huge bat glued against the side of his own house, a great square dark patch upon

the moonlit wall. Presently he tired of this amusement, and, dropping from branch to

branch, he squatted down into the old attitude and moved towards the stables, creeping

along in the same strange way as before. The wolfhound was out now, barking furiously, and

more excited than ever when it actually caught sight of its master. It was straining on

its chain and quivering with eagerness and rage. The professor squatted down very

deliberately just out of reach of the hound and began to provoke it in every possible way.

He took handfuls of pebbles from the drive and threw them in the dog’s face, prodded

him with a stick which he had picked up, flicked his hands about only a few inches from

the gaping mouth, and endeavoured in every way to increase the animal’s fury, which

was already beyond all control. In all our adventures I do not know that I have ever seen

a more strange sight than this impassive and still dignified figure crouching frog-like

upon the ground and goading to a wilder exhibition of passion the maddened hound, which

ramped and raged in front of him, by all manner of ingenious and calculated cruelty.

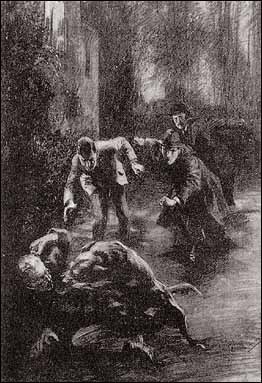

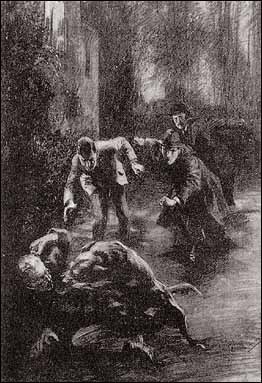

And then in a moment it happened! It was not the chain that

broke, but it was the collar that slipped, for it had been made for a thick-necked

Newfoundland. We heard the rattle of falling metal, and the next instant dog and man were

rolling on the ground together, the one roaring in rage, the other screaming in a strange

shrill falsetto of terror. It was a very narrow thing for the professor’s life. The

savage creature had him fairly by the throat, its fangs had bitten deep, and he was

senseless before we could reach them and drag the two apart. It might have been a

dangerous task for us, but Bennett’s voice and presence brought the great wolfhound

instantly to reason. The uproar had brought the sleepy and astonished coachman from his

room above the stables. “I’m not surprised,” said he, shaking his head.

“I’ve seen him at it before. I knew the dog would get him sooner or later.” And then in a moment it happened! It was not the chain that

broke, but it was the collar that slipped, for it had been made for a thick-necked

Newfoundland. We heard the rattle of falling metal, and the next instant dog and man were

rolling on the ground together, the one roaring in rage, the other screaming in a strange

shrill falsetto of terror. It was a very narrow thing for the professor’s life. The

savage creature had him fairly by the throat, its fangs had bitten deep, and he was

senseless before we could reach them and drag the two apart. It might have been a

dangerous task for us, but Bennett’s voice and presence brought the great wolfhound

instantly to reason. The uproar had brought the sleepy and astonished coachman from his

room above the stables. “I’m not surprised,” said he, shaking his head.

“I’ve seen him at it before. I knew the dog would get him sooner or later.”

The hound was secured, and together we carried the

professor up to his room, where Bennett, who had a medical degree, helped me to dress his

torn throat. The sharp teeth had passed dangerously near the carotid artery, and the

haemorrhage was serious. In half an hour the danger was past, I had given the patient an

injection of morphia, and he had sunk into deep sleep. Then, and only then, were we able

to look at each other and to take stock of the situation. The hound was secured, and together we carried the

professor up to his room, where Bennett, who had a medical degree, helped me to dress his

torn throat. The sharp teeth had passed dangerously near the carotid artery, and the

haemorrhage was serious. In half an hour the danger was past, I had given the patient an

injection of morphia, and he had sunk into deep sleep. Then, and only then, were we able

to look at each other and to take stock of the situation.

“I think a first-class surgeon should see him,” said

I. “I think a first-class surgeon should see him,” said

I.

“For God’s sake, no!” cried Bennett. “At

present the scandal is confined to our own household. It is safe with us. If it gets

beyond these walls it will never stop. Consider his position at the university, his

European reputation, the feelings of his daughter.” “For God’s sake, no!” cried Bennett. “At

present the scandal is confined to our own household. It is safe with us. If it gets

beyond these walls it will never stop. Consider his position at the university, his

European reputation, the feelings of his daughter.”

[1082] “Quite

so,” said Holmes. “I think it may be quite possible to keep the matter to

ourselves, and also to prevent its recurrence now that we have a free hand. The key from

the watch-chain, Mr. Bennett. Macphail will guard the patient and let us know if there is

any change. Let us see what we can find in the professor’s mysterious box.” [1082] “Quite

so,” said Holmes. “I think it may be quite possible to keep the matter to

ourselves, and also to prevent its recurrence now that we have a free hand. The key from

the watch-chain, Mr. Bennett. Macphail will guard the patient and let us know if there is

any change. Let us see what we can find in the professor’s mysterious box.”

There was not much, but there was enough–an empty phial,

another nearly full, a hypodermic syringe, several letters in a crabbed, foreign hand. The

marks on the envelopes showed that they were those which had disturbed the routine of the

secretary, and each was dated from the Commercial Road and signed “A. Dorak.”

They were mere invoices to say that a fresh bottle was being sent to Professor Presbury,

or receipt to acknowledge money. There was one other envelope, however, in a more educated

hand and bearing the Austrian stamp with the postmark of Prague. “Here we have our

material!” cried Holmes as he tore out the enclosure. There was not much, but there was enough–an empty phial,

another nearly full, a hypodermic syringe, several letters in a crabbed, foreign hand. The

marks on the envelopes showed that they were those which had disturbed the routine of the

secretary, and each was dated from the Commercial Road and signed “A. Dorak.”

They were mere invoices to say that a fresh bottle was being sent to Professor Presbury,

or receipt to acknowledge money. There was one other envelope, however, in a more educated

hand and bearing the Austrian stamp with the postmark of Prague. “Here we have our

material!” cried Holmes as he tore out the enclosure.

- HONOURED COLLEAGUE [it ran]:

Since your esteemed visit I have thought much of your case,

and though in your circumstances there are some special reasons for the treatment, I would

none the less enjoin caution, as my results have shown that it is not without danger of a

kind. Since your esteemed visit I have thought much of your case,

and though in your circumstances there are some special reasons for the treatment, I would

none the less enjoin caution, as my results have shown that it is not without danger of a

kind.

It is possible that the serum of anthropoid would have been

better. I have, as I explained to you, used black-faced langur because a specimen was

accessible. Langur is, of course, a crawler and climber, while anthropoid walks erect and

is in all ways nearer. It is possible that the serum of anthropoid would have been

better. I have, as I explained to you, used black-faced langur because a specimen was

accessible. Langur is, of course, a crawler and climber, while anthropoid walks erect and

is in all ways nearer.

I beg you to take every possible precaution that there be no

premature revelation of the process. I have one other client in England, and Dorak is my

agent for both. I beg you to take every possible precaution that there be no

premature revelation of the process. I have one other client in England, and Dorak is my

agent for both.

Weekly reports will oblige. Weekly reports will oblige.

- Yours with high esteem,

- H. LOWENSTEIN.

Lowenstein! The name brought back to me the memory of some

snippet from a newspaper which spoke of an obscure scientist who was striving in some

unknown way for the secret of rejuvenescence and the elixir of life. Lowenstein of Prague!

Lowenstein with the wondrous strength-giving serum, tabooed by the profession because he

refused to reveal its source. In a few words I said what I remembered. Bennett had taken a

manual of zoology from the shelves. “ ‘Langur,’ ” he read, “

‘the great black-faced monkey of the Himalayan slopes, biggest and most human of

climbing monkeys.’ Many details are added. Well, thanks to you, Mr. Holmes, it is

very clear that we have traced the evil to its source.” Lowenstein! The name brought back to me the memory of some

snippet from a newspaper which spoke of an obscure scientist who was striving in some

unknown way for the secret of rejuvenescence and the elixir of life. Lowenstein of Prague!

Lowenstein with the wondrous strength-giving serum, tabooed by the profession because he

refused to reveal its source. In a few words I said what I remembered. Bennett had taken a

manual of zoology from the shelves. “ ‘Langur,’ ” he read, “

‘the great black-faced monkey of the Himalayan slopes, biggest and most human of

climbing monkeys.’ Many details are added. Well, thanks to you, Mr. Holmes, it is

very clear that we have traced the evil to its source.”

“The real source,” said Holmes, “lies, of

course, in that untimely love affair which gave our impetuous professor the idea that he

could only gain his wish by turning himself into a younger man. When one tries to rise

above Nature one is liable to fall below it. The highest type of man may revert to the

animal if he leaves the straight road of destiny.” He sat musing for a little with

the phial in his hand, looking at the clear liquid within. “When I have written to

this man and told him that I hold him criminally responsible for the poisons which he

circulates, we will have no more trouble. But it may recur. Others may find a better way.

There is danger there–a very real danger to humanity. Consider, Watson, that the

material, the sensual, the worldly would all prolong their worthless lives. [1083] The spiritual would not avoid the

call to something higher. It would be the survival of the least fit. What sort of cesspool

may not our poor world become?” Suddenly the dreamer disappeared, and Holmes, the man

of action, sprang from his chair. “I think there is nothing more to be said, Mr.

Bennett. The various incidents will now fit themselves easily into the general scheme. The

dog, of course, was aware of the change far more quickly than you. His smell would insure

that. It was the monkey, not the professor, whom Roy attacked, just as it was the monkey

who teased Roy. Climbing was a joy to the creature, and it was a mere chance, I take it,

that the pastime brought him to the young lady’s window. There is an early train to

town, Watson, but I think we shall just have time for a cup of tea at the Chequers before

we catch it.” “The real source,” said Holmes, “lies, of

course, in that untimely love affair which gave our impetuous professor the idea that he

could only gain his wish by turning himself into a younger man. When one tries to rise

above Nature one is liable to fall below it. The highest type of man may revert to the

animal if he leaves the straight road of destiny.” He sat musing for a little with

the phial in his hand, looking at the clear liquid within. “When I have written to

this man and told him that I hold him criminally responsible for the poisons which he

circulates, we will have no more trouble. But it may recur. Others may find a better way.

There is danger there–a very real danger to humanity. Consider, Watson, that the

material, the sensual, the worldly would all prolong their worthless lives. [1083] The spiritual would not avoid the

call to something higher. It would be the survival of the least fit. What sort of cesspool

may not our poor world become?” Suddenly the dreamer disappeared, and Holmes, the man

of action, sprang from his chair. “I think there is nothing more to be said, Mr.

Bennett. The various incidents will now fit themselves easily into the general scheme. The

dog, of course, was aware of the change far more quickly than you. His smell would insure

that. It was the monkey, not the professor, whom Roy attacked, just as it was the monkey

who teased Roy. Climbing was a joy to the creature, and it was a mere chance, I take it,

that the pastime brought him to the young lady’s window. There is an early train to

town, Watson, but I think we shall just have time for a cup of tea at the Chequers before

we catch it.”

|

![]() It was one Sunday evening early in September of the year 1903

that I received one of Holmes’s laconic messages:

It was one Sunday evening early in September of the year 1903

that I received one of Holmes’s laconic messages: Come at once if convenient–if inconvenient come all the

same.

Come at once if convenient–if inconvenient come all the

same.