|

|

Holmes examined it for some time, and then, folding it carefully up, he placed it in his

pocketbook.

“This promises to be a most interesting and unusual

case,” said he. “You gave me a few particulars in your letter, Mr. Hilton

Cubitt, but I should be very much obliged if you would kindly go over it all again for the

benefit of my friend, Dr. Watson.” “This promises to be a most interesting and unusual

case,” said he. “You gave me a few particulars in your letter, Mr. Hilton

Cubitt, but I should be very much obliged if you would kindly go over it all again for the

benefit of my friend, Dr. Watson.”

“I’m not much of a story-teller,” said our

visitor, nervously clasping and unclasping his great, strong hands. “You’ll just

ask me anything that I don’t make clear. I’ll begin at the time of my marriage

last year, but I want to say first of all that, though I’m not a rich man, my people

have been at Riding Thorpe for a matter of five centuries, and there is no better known

family in the County of Norfolk. Last year I came up to London for the Jubilee, and I

stopped at a boardinghouse in Russell Square, because Parker, the vicar of our parish, was

staying in it. There was an American young lady there–Patrick was the name–Elsie

Patrick. In some way we became friends, until before my month was up I was as much in love

as man could be. We were quietly married at a registry office, and we returned to Norfolk

a wedded couple. You’ll think it very mad, Mr. Holmes, that a man of a good old

family should marry a wife in this fashion, knowing nothing of her past or of her people,

but if you saw her and knew her, it would help you to understand. “I’m not much of a story-teller,” said our

visitor, nervously clasping and unclasping his great, strong hands. “You’ll just

ask me anything that I don’t make clear. I’ll begin at the time of my marriage

last year, but I want to say first of all that, though I’m not a rich man, my people

have been at Riding Thorpe for a matter of five centuries, and there is no better known

family in the County of Norfolk. Last year I came up to London for the Jubilee, and I

stopped at a boardinghouse in Russell Square, because Parker, the vicar of our parish, was

staying in it. There was an American young lady there–Patrick was the name–Elsie

Patrick. In some way we became friends, until before my month was up I was as much in love

as man could be. We were quietly married at a registry office, and we returned to Norfolk

a wedded couple. You’ll think it very mad, Mr. Holmes, that a man of a good old

family should marry a wife in this fashion, knowing nothing of her past or of her people,

but if you saw her and knew her, it would help you to understand.

“She was very straight about it, was Elsie. I can’t

say that she did not give me [513] every

chance of getting out of it if I wished to do so. ‘I have had some very disagreeable

associations in my life,’ said she, ‘I wish to forget all about them. I would

rather never allude to the past, for it is very painful to me. If you take me, Hilton, you

will take a woman who has nothing that she need be personally ashamed of; but you will

have to be content with my word for it, and to allow me to be silent as to all that passed

up to the time when I became yours. If these conditions are too hard, then go back to

Norfolk, and leave me to the lonely life in which you found me.’ It was only the day

before our wedding that she said those very words to me. I told her that I was content to

take her on her own terms, and I have been as good as my word. “She was very straight about it, was Elsie. I can’t

say that she did not give me [513] every

chance of getting out of it if I wished to do so. ‘I have had some very disagreeable

associations in my life,’ said she, ‘I wish to forget all about them. I would

rather never allude to the past, for it is very painful to me. If you take me, Hilton, you

will take a woman who has nothing that she need be personally ashamed of; but you will

have to be content with my word for it, and to allow me to be silent as to all that passed

up to the time when I became yours. If these conditions are too hard, then go back to

Norfolk, and leave me to the lonely life in which you found me.’ It was only the day

before our wedding that she said those very words to me. I told her that I was content to

take her on her own terms, and I have been as good as my word.

“Well, we have been married now for a year, and very

happy we have been. But about a month ago, at the end of June, I saw for the first time

signs of trouble. One day my wife received a letter from America. I saw the American

stamp. She turned deadly white, read the letter, and threw it into the fire. She made no

allusion to it afterwards, and I made none, for a promise is a promise, but she has never

known an easy hour from that moment. There is always a look of fear upon her face–a

look as if she were waiting and expecting. She would do better to trust me. She would find

that I was her best friend. But until she speaks, I can say nothing. Mind you, she is a

truthful woman, Mr. Holmes, and whatever trouble there may have been in her past life it

has been no fault of hers. I am only a simple Norfolk squire, but there is not a man in

England who ranks his family honour more highly than I do. She knows it well, and she knew

it well before she married me. She would never bring any stain upon it–of that I am

sure. “Well, we have been married now for a year, and very

happy we have been. But about a month ago, at the end of June, I saw for the first time

signs of trouble. One day my wife received a letter from America. I saw the American

stamp. She turned deadly white, read the letter, and threw it into the fire. She made no

allusion to it afterwards, and I made none, for a promise is a promise, but she has never

known an easy hour from that moment. There is always a look of fear upon her face–a

look as if she were waiting and expecting. She would do better to trust me. She would find

that I was her best friend. But until she speaks, I can say nothing. Mind you, she is a

truthful woman, Mr. Holmes, and whatever trouble there may have been in her past life it

has been no fault of hers. I am only a simple Norfolk squire, but there is not a man in

England who ranks his family honour more highly than I do. She knows it well, and she knew

it well before she married me. She would never bring any stain upon it–of that I am

sure.

“Well, now I come to the queer part of my story. About a

week ago–it was the Tuesday of last week–I found on one of the window-sills a

number of absurd little dancing figures like these upon the paper. They were scrawled with

chalk. I thought that it was the stable-boy who had drawn them, but the lad swore he knew

nothing about it. Anyhow, they had come there during the night. I had them washed out, and

I only mentioned the matter to my wife afterwards. To my surprise, she took it very

seriously, and begged me if any more came to let her see them. None did come for a week,

and then yesterday morning I found this paper lying on the sundial in the garden. I showed

it to Elsie, and down she dropped in a dead faint. Since then she has looked like a woman

in a dream, half dazed, and with terror always lurking in her eyes. It was then that I

wrote and sent the paper to you, Mr. Holmes. It was not a thing that I could take to the

police, for they would have laughed at me, but you will tell me what to do. I am not a

rich man, but if there is any danger threatening my little woman, I would spend my last

copper to shield her.” “Well, now I come to the queer part of my story. About a

week ago–it was the Tuesday of last week–I found on one of the window-sills a

number of absurd little dancing figures like these upon the paper. They were scrawled with

chalk. I thought that it was the stable-boy who had drawn them, but the lad swore he knew

nothing about it. Anyhow, they had come there during the night. I had them washed out, and

I only mentioned the matter to my wife afterwards. To my surprise, she took it very

seriously, and begged me if any more came to let her see them. None did come for a week,

and then yesterday morning I found this paper lying on the sundial in the garden. I showed

it to Elsie, and down she dropped in a dead faint. Since then she has looked like a woman

in a dream, half dazed, and with terror always lurking in her eyes. It was then that I

wrote and sent the paper to you, Mr. Holmes. It was not a thing that I could take to the

police, for they would have laughed at me, but you will tell me what to do. I am not a

rich man, but if there is any danger threatening my little woman, I would spend my last

copper to shield her.”

He was a fine creature, this man of the old English

soil–simple, straight, and gentle, with his great, earnest blue eyes and broad,

comely face. His love for his wife and his trust in her shone in his features. Holmes had

listened to his story with the utmost attention, and now he sat for some time in silent

thought. He was a fine creature, this man of the old English

soil–simple, straight, and gentle, with his great, earnest blue eyes and broad,

comely face. His love for his wife and his trust in her shone in his features. Holmes had

listened to his story with the utmost attention, and now he sat for some time in silent

thought.

“Don’t you think, Mr. Cubitt,” said he, at

last, “that your best plan would be to make a direct appeal to your wife, and to ask

her to share her secret with you?” “Don’t you think, Mr. Cubitt,” said he, at

last, “that your best plan would be to make a direct appeal to your wife, and to ask

her to share her secret with you?”

Hilton Cubitt shook his massive head. Hilton Cubitt shook his massive head.

“A promise is a promise, Mr. Holmes. If Elsie wished to

tell me she would. If not, it is not for me to force her confidence. But I am justified in

taking my own line–and I will.” “A promise is a promise, Mr. Holmes. If Elsie wished to

tell me she would. If not, it is not for me to force her confidence. But I am justified in

taking my own line–and I will.”

“Then I will help you with all my heart. In the first

place, have you heard of any strangers being seen in your neighbourhood?” “Then I will help you with all my heart. In the first

place, have you heard of any strangers being seen in your neighbourhood?”

[514] “No.” [514] “No.”

“I presume that it is a very quiet place. Any fresh face

would cause comment?” “I presume that it is a very quiet place. Any fresh face

would cause comment?”

“In the immediate neighbourhood, yes. But we have several

small watering-places not very far away. And the farmers take in lodgers.” “In the immediate neighbourhood, yes. But we have several

small watering-places not very far away. And the farmers take in lodgers.”

“These hieroglyphics have evidently a meaning. If it is a

purely arbitrary one, it may be impossible for us to solve it. If, on the other hand, it

is systematic, I have no doubt that we shall get to the bottom of it. But this particular

sample is so short that I can do nothing, and the facts which you have brought me are so

indefinite that we have no basis for an investigation. I would suggest that you return to

Norfolk, that you keep a keen lookout, and that you take an exact copy of any fresh

dancing men which may appear. It is a thousand pities that we have not a reproduction of

those which were done in chalk upon the window-sill. Make a discreet inquiry also as to

any strangers in the neighbourhood. When you have collected some fresh evidence, come to

me again. That is the best advice which I can give you, Mr. Hilton Cubitt. If there are

any pressing fresh developments, I shall be always ready to run down and see you in your

Norfolk home.” “These hieroglyphics have evidently a meaning. If it is a

purely arbitrary one, it may be impossible for us to solve it. If, on the other hand, it

is systematic, I have no doubt that we shall get to the bottom of it. But this particular

sample is so short that I can do nothing, and the facts which you have brought me are so

indefinite that we have no basis for an investigation. I would suggest that you return to

Norfolk, that you keep a keen lookout, and that you take an exact copy of any fresh

dancing men which may appear. It is a thousand pities that we have not a reproduction of

those which were done in chalk upon the window-sill. Make a discreet inquiry also as to

any strangers in the neighbourhood. When you have collected some fresh evidence, come to

me again. That is the best advice which I can give you, Mr. Hilton Cubitt. If there are

any pressing fresh developments, I shall be always ready to run down and see you in your

Norfolk home.”

The interview left Sherlock Holmes very thoughtful, and

several times in the next few days I saw him take his slip of paper from his notebook and

look long and earnestly at the curious figures inscribed upon it. He made no allusion to

the affair, however, until one afternoon a fortnight or so later. I was going out when he

called me back. The interview left Sherlock Holmes very thoughtful, and

several times in the next few days I saw him take his slip of paper from his notebook and

look long and earnestly at the curious figures inscribed upon it. He made no allusion to

the affair, however, until one afternoon a fortnight or so later. I was going out when he

called me back.

“You had better stay here, Watson.” “You had better stay here, Watson.”

“Why?” “Why?”

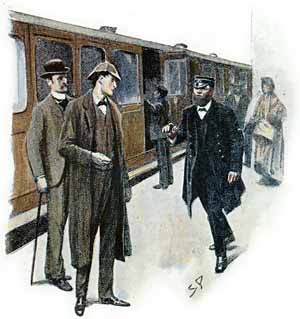

“Because I had a wire from Hilton Cubitt this morning.

You remember Hilton Cubitt, of the dancing men? He was to reach Liverpool Street at

one-twenty. He may be here at any moment. I gather from his wire that there have been some

new incidents of importance.” “Because I had a wire from Hilton Cubitt this morning.

You remember Hilton Cubitt, of the dancing men? He was to reach Liverpool Street at

one-twenty. He may be here at any moment. I gather from his wire that there have been some

new incidents of importance.”

We had not long to wait, for our Norfolk squire came straight

from the station as fast as a hansom could bring him. He was looking worried and

depressed, with tired eyes and a lined forehead. We had not long to wait, for our Norfolk squire came straight

from the station as fast as a hansom could bring him. He was looking worried and

depressed, with tired eyes and a lined forehead.

“It’s getting on my nerves, this business, Mr.

Holmes,” said he, as he sank, like a wearied man, into an armchair. “It’s

bad enough to feel that you are surrounded by unseen, unknown folk, who have some kind of

design upon you, but when, in addition to that, you know that it is just killing your wife

by inches, then it becomes as much as flesh and blood can endure. She’s wearing away

under it–just wearing away before my eyes.” “It’s getting on my nerves, this business, Mr.

Holmes,” said he, as he sank, like a wearied man, into an armchair. “It’s

bad enough to feel that you are surrounded by unseen, unknown folk, who have some kind of

design upon you, but when, in addition to that, you know that it is just killing your wife

by inches, then it becomes as much as flesh and blood can endure. She’s wearing away

under it–just wearing away before my eyes.”

“Has she said anything yet?” “Has she said anything yet?”

“No, Mr. Holmes, she has not. And yet there have been

times when the poor girl has wanted to speak, and yet could not quite bring herself to

take the plunge. I have tried to help her, but I daresay I did it clumsily, and scared her

from it. She has spoken about my old family, and our reputation in the county, and our

pride in our unsullied honour, and I always felt it was leading to the point, but somehow

it turned off before we got there.” “No, Mr. Holmes, she has not. And yet there have been

times when the poor girl has wanted to speak, and yet could not quite bring herself to

take the plunge. I have tried to help her, but I daresay I did it clumsily, and scared her

from it. She has spoken about my old family, and our reputation in the county, and our

pride in our unsullied honour, and I always felt it was leading to the point, but somehow

it turned off before we got there.”

“But you have found out something for yourself?” “But you have found out something for yourself?”

“A good deal, Mr. Holmes. I have several fresh

dancing-men pictures for you to examine, and, what is more important, I have seen the

fellow.” “A good deal, Mr. Holmes. I have several fresh

dancing-men pictures for you to examine, and, what is more important, I have seen the

fellow.”

“What, the man who draws them?” “What, the man who draws them?”

“Yes, I saw him at his work. But I will tell you

everything in order. When I got back after my visit to you, the very first thing I saw

next morning was a fresh [515] crop

of dancing men. They had been drawn in chalk upon the black wooden door of the tool-house,

which stands beside the lawn in full view of the front windows. I took an exact copy, and

here it is.” He unfolded a paper and laid it upon the table. Here is a copy of the

hieroglyphics: “Yes, I saw him at his work. But I will tell you

everything in order. When I got back after my visit to you, the very first thing I saw

next morning was a fresh [515] crop

of dancing men. They had been drawn in chalk upon the black wooden door of the tool-house,

which stands beside the lawn in full view of the front windows. I took an exact copy, and

here it is.” He unfolded a paper and laid it upon the table. Here is a copy of the

hieroglyphics:

“Excellent!” said Holmes. “Excellent! Pray

continue.” “Excellent!” said Holmes. “Excellent! Pray

continue.”

“When I had taken the copy, I rubbed out the marks, but,

two mornings later, a fresh inscription had appeared. I have a copy of it here”: “When I had taken the copy, I rubbed out the marks, but,

two mornings later, a fresh inscription had appeared. I have a copy of it here”:

Holmes rubbed his hands and chuckled with delight. Holmes rubbed his hands and chuckled with delight.

“Our material is rapidly accumulating,” said he. “Our material is rapidly accumulating,” said he.

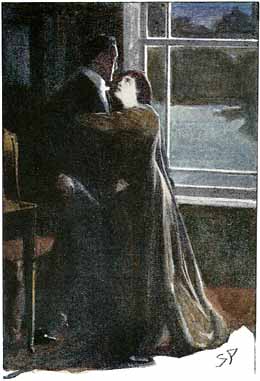

“Three days later a message was left scrawled upon paper,

and placed under a pebble upon the sundial. Here it is. The characters are, as you see,

exactly the same as the last one. After that I determined to lie in wait, so I got out my

revolver and I sat up in my study, which overlooks the lawn and garden. About two in the

morning I was seated by the window, all being dark save for the moonlight outside, when I

heard steps behind me, and there was my wife in her dressing-gown. She implored me to come

to bed. I told her frankly that I wished to see who it was who played such absurd tricks

upon us. She answered that it was some senseless practical joke, and that I should not

take any notice of it. “Three days later a message was left scrawled upon paper,

and placed under a pebble upon the sundial. Here it is. The characters are, as you see,

exactly the same as the last one. After that I determined to lie in wait, so I got out my

revolver and I sat up in my study, which overlooks the lawn and garden. About two in the

morning I was seated by the window, all being dark save for the moonlight outside, when I

heard steps behind me, and there was my wife in her dressing-gown. She implored me to come

to bed. I told her frankly that I wished to see who it was who played such absurd tricks

upon us. She answered that it was some senseless practical joke, and that I should not

take any notice of it.

“ ‘If it really annoys you, Hilton, we might go and

travel, you and I, and so avoid this nuisance.’ “ ‘If it really annoys you, Hilton, we might go and

travel, you and I, and so avoid this nuisance.’

“ ‘What, be driven out of our own house by a

practical joker?’ said I. ‘Why, we should have the whole county laughing at

us.’ “ ‘What, be driven out of our own house by a

practical joker?’ said I. ‘Why, we should have the whole county laughing at

us.’

“ ‘Well, come to bed,’ said she, ‘and we

can discuss it in the morning.’ “ ‘Well, come to bed,’ said she, ‘and we

can discuss it in the morning.’

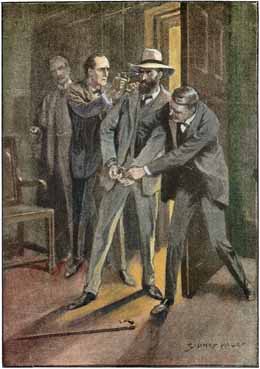

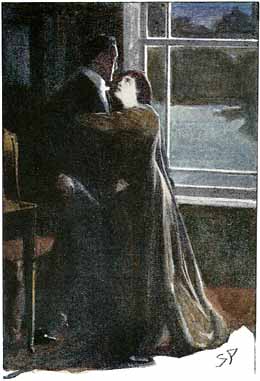

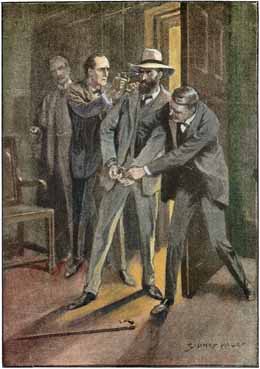

“Suddenly, as she spoke, I saw her white face grow

whiter yet in the moonlight, and her hand tightened upon my shoulder. Something was moving

in the shadow of the tool-house. I saw a dark, creeping figure which crawled round the

corner and squatted in front of the door. Seizing my pistol, I was rushing out, when my

wife threw her arms round me and held me with convulsive strength. I tried to throw her

off, but she clung to me most desperately. At last I got clear, but by the time I had

opened the door and reached the house the creature was gone. He had left a trace of his

presence, however, for there on the door was the very same arrangement of dancing men

which had already twice appeared, and which I have copied on that paper. There was no

other sign of the fellow anywhere, though I ran all over the grounds. And yet the amazing

thing is that he must have been there all the time, for when I examined the door again in

the morning, he had scrawled some more of his pictures under the line which I had already

seen.” “Suddenly, as she spoke, I saw her white face grow

whiter yet in the moonlight, and her hand tightened upon my shoulder. Something was moving

in the shadow of the tool-house. I saw a dark, creeping figure which crawled round the

corner and squatted in front of the door. Seizing my pistol, I was rushing out, when my

wife threw her arms round me and held me with convulsive strength. I tried to throw her

off, but she clung to me most desperately. At last I got clear, but by the time I had

opened the door and reached the house the creature was gone. He had left a trace of his

presence, however, for there on the door was the very same arrangement of dancing men

which had already twice appeared, and which I have copied on that paper. There was no

other sign of the fellow anywhere, though I ran all over the grounds. And yet the amazing

thing is that he must have been there all the time, for when I examined the door again in

the morning, he had scrawled some more of his pictures under the line which I had already

seen.”

“Have you that fresh drawing?” “Have you that fresh drawing?”

“Yes, it is very short, but I made a copy of it, and here

it is.” “Yes, it is very short, but I made a copy of it, and here

it is.”

Again he produced a paper. The new dance was in this form: Again he produced a paper. The new dance was in this form:

“Tell me,” said Holmes–and I could see by

his eyes that he was much excited–“was this a mere addition to the first or did

it appear to be entirely separate?” “Tell me,” said Holmes–and I could see by

his eyes that he was much excited–“was this a mere addition to the first or did

it appear to be entirely separate?”

“It was on a different panel of the door.” “It was on a different panel of the door.”

[516] “Excellent!

This is far the most important of all for our purpose. It fills me with hopes. Now, Mr.

Hilton Cubitt, please continue your most interesting statement.” [516] “Excellent!

This is far the most important of all for our purpose. It fills me with hopes. Now, Mr.

Hilton Cubitt, please continue your most interesting statement.”

“I have nothing more to say, Mr. Holmes, except that I

was angry with my wife that night for having held me back when I might have caught the

skulking rascal. She said that she feared that I might come to harm. For an instant it had

crossed my mind that perhaps what she really feared was that he might come to

harm, for I could not doubt that she knew who this man was, and what he meant by these

strange signals. But there is a tone in my wife’s voice, Mr. Holmes, and a look in

her eyes which forbid doubt, and I am sure that it was indeed my own safety that was in

her mind. There’s the whole case, and now I want your advice as to what I ought to

do. My own inclination is to put half a dozen of my farm lads in the shrubbery, and when

this fellow comes again to give him such a hiding that he will leave us in peace for the

future.” “I have nothing more to say, Mr. Holmes, except that I

was angry with my wife that night for having held me back when I might have caught the

skulking rascal. She said that she feared that I might come to harm. For an instant it had

crossed my mind that perhaps what she really feared was that he might come to

harm, for I could not doubt that she knew who this man was, and what he meant by these

strange signals. But there is a tone in my wife’s voice, Mr. Holmes, and a look in

her eyes which forbid doubt, and I am sure that it was indeed my own safety that was in

her mind. There’s the whole case, and now I want your advice as to what I ought to

do. My own inclination is to put half a dozen of my farm lads in the shrubbery, and when

this fellow comes again to give him such a hiding that he will leave us in peace for the

future.”

“I fear it is too deep a case for such simple

remedies,” said Holmes. “How long can you stay in London?” “I fear it is too deep a case for such simple

remedies,” said Holmes. “How long can you stay in London?”

“I must go back to-day. I would not leave my wife alone

all night for anything. She is very nervous, and begged me to come back.” “I must go back to-day. I would not leave my wife alone

all night for anything. She is very nervous, and begged me to come back.”

“I daresay you are right. But if you could have stopped,

I might possibly have been able to return with you in a day or two. Meanwhile you will

leave me these papers, and I think that it is very likely that I shall be able to pay you

a visit shortly and to throw some light upon your case.” “I daresay you are right. But if you could have stopped,

I might possibly have been able to return with you in a day or two. Meanwhile you will

leave me these papers, and I think that it is very likely that I shall be able to pay you

a visit shortly and to throw some light upon your case.”

Sherlock Holmes preserved his calm professional manner until

our visitor had left us, although it was easy for me, who knew him so well, to see that he

was profoundly excited. The moment that Hilton Cubitt’s broad back had disappeared

through the door my comrade rushed to the table, laid out all the slips of paper

containing dancing men in front of him, and threw himself into an intricate and elaborate

calculation. For two hours I watched him as he covered sheet after sheet of paper with

figures and letters, so completely absorbed in his task that he had evidently forgotten my

presence. Sometimes he was making progress and whistled and sang at his work; sometimes he

was puzzled, and would sit for long spells with a furrowed brow and a vacant eye. Finally

he sprang from his chair with a cry of satisfaction, and walked up and down the room

rubbing his hands together. Then he wrote a long telegram upon a cable form. “If my

answer to this is as I hope, you will have a very pretty case to add to your collection,

Watson,” said he. “I expect that we shall be able to go down to Norfolk

to-morrow, and to take our friend some very definite news as to the secret of his

annoyance.” Sherlock Holmes preserved his calm professional manner until

our visitor had left us, although it was easy for me, who knew him so well, to see that he

was profoundly excited. The moment that Hilton Cubitt’s broad back had disappeared

through the door my comrade rushed to the table, laid out all the slips of paper

containing dancing men in front of him, and threw himself into an intricate and elaborate

calculation. For two hours I watched him as he covered sheet after sheet of paper with

figures and letters, so completely absorbed in his task that he had evidently forgotten my

presence. Sometimes he was making progress and whistled and sang at his work; sometimes he

was puzzled, and would sit for long spells with a furrowed brow and a vacant eye. Finally

he sprang from his chair with a cry of satisfaction, and walked up and down the room

rubbing his hands together. Then he wrote a long telegram upon a cable form. “If my

answer to this is as I hope, you will have a very pretty case to add to your collection,

Watson,” said he. “I expect that we shall be able to go down to Norfolk

to-morrow, and to take our friend some very definite news as to the secret of his

annoyance.”

I confess that I was filled with curiosity, but I was aware

that Holmes liked to make his disclosures at his own time and in his own way, so I waited

until it should suit him to take me into his confidence. I confess that I was filled with curiosity, but I was aware

that Holmes liked to make his disclosures at his own time and in his own way, so I waited

until it should suit him to take me into his confidence.

But there was a delay in that answering telegram, and two days

of impatience followed, during which Holmes pricked up his ears at every ring of the bell.

On the evening of the second there came a letter from Hilton Cubitt. All was quiet with

him, save that a long inscription had appeared that morning upon the pedestal of the

sundial. He inclosed a copy of it, which is here reproduced: But there was a delay in that answering telegram, and two days

of impatience followed, during which Holmes pricked up his ears at every ring of the bell.

On the evening of the second there came a letter from Hilton Cubitt. All was quiet with

him, save that a long inscription had appeared that morning upon the pedestal of the

sundial. He inclosed a copy of it, which is here reproduced:

[517] Holmes

bent over this grotesque frieze for some minutes, and then suddenly sprang to his feet

with an exclamation of surprise and dismay. His face was haggard with anxiety. [517] Holmes

bent over this grotesque frieze for some minutes, and then suddenly sprang to his feet

with an exclamation of surprise and dismay. His face was haggard with anxiety.

“We have let this affair go far enough,” said he.

“Is there a train to North Walsham to-night?” “We have let this affair go far enough,” said he.

“Is there a train to North Walsham to-night?”

I turned up the time-table. The last had just gone. I turned up the time-table. The last had just gone.

“Then we shall breakfast early and take the very first in

the morning,” said Holmes. “Our presence is most urgently needed. Ah! here is

our expected cablegram. One moment, Mrs. Hudson, there may be an answer. No, that is quite

as I expected. This message makes it even more essential that we should not lose an hour

in letting Hilton Cubitt know how matters stand, for it is a singular and a dangerous web

in which our simple Norfolk squire is entangled.” “Then we shall breakfast early and take the very first in

the morning,” said Holmes. “Our presence is most urgently needed. Ah! here is

our expected cablegram. One moment, Mrs. Hudson, there may be an answer. No, that is quite

as I expected. This message makes it even more essential that we should not lose an hour

in letting Hilton Cubitt know how matters stand, for it is a singular and a dangerous web

in which our simple Norfolk squire is entangled.”

So, indeed, it proved, and as I come to the dark conclusion of

a story which had seemed to me to be only childish and bizarre, I experience once again

the dismay and horror with which I was filled. Would that I had some brighter ending to

communicate to my readers, but these are the chronicles of fact, and I must follow to

their dark crisis the strange chain of events which for some days made Riding Thorpe Manor

a household word through the length and breadth of England. So, indeed, it proved, and as I come to the dark conclusion of

a story which had seemed to me to be only childish and bizarre, I experience once again

the dismay and horror with which I was filled. Would that I had some brighter ending to

communicate to my readers, but these are the chronicles of fact, and I must follow to

their dark crisis the strange chain of events which for some days made Riding Thorpe Manor

a household word through the length and breadth of England.

We had hardly alighted at North Walsham, and mentioned the

name of our destination, when the stationmaster hurried towards us. “I suppose that

you are the detectives from London?” said he. We had hardly alighted at North Walsham, and mentioned the

name of our destination, when the stationmaster hurried towards us. “I suppose that

you are the detectives from London?” said he.

A look of annoyance passed over Holmes’s face. A look of annoyance passed over Holmes’s face.

“What makes you think such a thing?” “What makes you think such a thing?”

“Because Inspector Martin from Norwich has just passed

through. But maybe you are the surgeons. She’s not dead–or wasn’t by last

accounts. You may be in time to save her yet–though it be for the gallows.” “Because Inspector Martin from Norwich has just passed

through. But maybe you are the surgeons. She’s not dead–or wasn’t by last

accounts. You may be in time to save her yet–though it be for the gallows.”

Holmes’s brow was dark with anxiety. Holmes’s brow was dark with anxiety.

“We are going to Riding Thorpe Manor,” said he,

“but we have heard nothing of what has passed there.” “We are going to Riding Thorpe Manor,” said he,

“but we have heard nothing of what has passed there.”

“It’s a terrible business,” said the

stationmaster. “They are shot, both Mr. Hilton Cubitt and his wife. She shot him and

then herself–so the servants say. He’s dead and her life is despaired of. Dear,

dear, one of the oldest families in the county of Norfolk, and one of the most

honoured.” “It’s a terrible business,” said the

stationmaster. “They are shot, both Mr. Hilton Cubitt and his wife. She shot him and

then herself–so the servants say. He’s dead and her life is despaired of. Dear,

dear, one of the oldest families in the county of Norfolk, and one of the most

honoured.”

Without a word Holmes hurried to a carriage, and during the

long seven miles’ drive he never opened his mouth. Seldom have I seen him so utterly

despondent. He had been uneasy during all our journey from town, and I had observed that

he had turned over the morning papers with anxious attention, but now this sudden

realization of his worst fears left him in a blank melancholy. He leaned back in his seat,

lost in gloomy speculation. Yet there was much around to interest us, for we were passing

through as singular a countryside as any in England, where a few scattered cottages

represented the population of to-day, while on every hand enormous square-towered churches

bristled up from the flat green landscape and told of the glory and prosperity of old East

Anglia. At last the violet rim of the German Ocean appeared over the green edge of the

Norfolk coast, and the driver pointed with his whip to two old brick and timber gables

which projected from a grove of trees. “That’s Riding Thorpe Manor,” said

he. Without a word Holmes hurried to a carriage, and during the

long seven miles’ drive he never opened his mouth. Seldom have I seen him so utterly

despondent. He had been uneasy during all our journey from town, and I had observed that

he had turned over the morning papers with anxious attention, but now this sudden

realization of his worst fears left him in a blank melancholy. He leaned back in his seat,

lost in gloomy speculation. Yet there was much around to interest us, for we were passing

through as singular a countryside as any in England, where a few scattered cottages

represented the population of to-day, while on every hand enormous square-towered churches

bristled up from the flat green landscape and told of the glory and prosperity of old East

Anglia. At last the violet rim of the German Ocean appeared over the green edge of the

Norfolk coast, and the driver pointed with his whip to two old brick and timber gables

which projected from a grove of trees. “That’s Riding Thorpe Manor,” said

he.

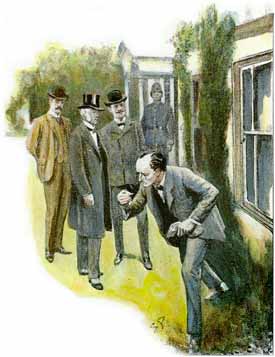

As we drove up to the porticoed front door, I observed in

front of it, beside the tennis lawn, the black tool-house and the pedestalled sundial with

which we had such strange associations. A dapper little man, with a quick, alert manner

and a [518] waxed moustache,

had just descended from a high dog-cart. He introduced himself as Inspector Martin, of the

Norfolk Constabulary, and he was considerably astonished when he heard the name of my

companion. As we drove up to the porticoed front door, I observed in

front of it, beside the tennis lawn, the black tool-house and the pedestalled sundial with

which we had such strange associations. A dapper little man, with a quick, alert manner

and a [518] waxed moustache,

had just descended from a high dog-cart. He introduced himself as Inspector Martin, of the

Norfolk Constabulary, and he was considerably astonished when he heard the name of my

companion.

“Why, Mr. Holmes, the crime was only committed at three

this morning. How could you hear of it in London and get to the spot as soon as I?” “Why, Mr. Holmes, the crime was only committed at three

this morning. How could you hear of it in London and get to the spot as soon as I?”

“I anticipated it. I came in the hope of preventing

it.” “I anticipated it. I came in the hope of preventing

it.”

“Then you must have important evidence, of which we are

ignorant, for they were said to be a most united couple.” “Then you must have important evidence, of which we are

ignorant, for they were said to be a most united couple.”

“I have only the evidence of the dancing men,” said

Holmes. “I will explain the matter to you later. Meanwhile, since it is too late to

prevent this tragedy, I am very anxious that I should use the knowledge which I possess in

order to insure that justice be done. Will you associate me in your investigation, or will

you prefer that I should act independently?” “I have only the evidence of the dancing men,” said

Holmes. “I will explain the matter to you later. Meanwhile, since it is too late to

prevent this tragedy, I am very anxious that I should use the knowledge which I possess in

order to insure that justice be done. Will you associate me in your investigation, or will

you prefer that I should act independently?”

“I should be proud to feel that we were acting together,

Mr. Holmes,” said the inspector, earnestly. “I should be proud to feel that we were acting together,

Mr. Holmes,” said the inspector, earnestly.

“In that case I should be glad to hear the evidence and

to examine the premises without an instant of unnecessary delay.” “In that case I should be glad to hear the evidence and

to examine the premises without an instant of unnecessary delay.”

Inspector Martin had the good sense to allow my friend to do

things in his own fashion, and contented himself with carefully noting the results. The

local surgeon, an old, white-haired man, had just come down from Mrs. Hilton Cubitt’s

room, and he reported that her injuries were serious, but not necessarily fatal. The

bullet had passed through the front of her brain, and it would probably be some time

before she could regain consciousness. On the question of whether she had been shot or had

shot herself, he would not venture to express any decided opinion. Certainly the bullet

had been discharged at very close quarters. There was only the one pistol found in the

room, two barrels of which had been emptied. Mr. Hilton Cubitt had been shot through the

heart. It was equally conceivable that he had shot her and then himself, or that she had

been the criminal, for the revolver lay upon the floor midway between them. Inspector Martin had the good sense to allow my friend to do

things in his own fashion, and contented himself with carefully noting the results. The

local surgeon, an old, white-haired man, had just come down from Mrs. Hilton Cubitt’s

room, and he reported that her injuries were serious, but not necessarily fatal. The

bullet had passed through the front of her brain, and it would probably be some time

before she could regain consciousness. On the question of whether she had been shot or had

shot herself, he would not venture to express any decided opinion. Certainly the bullet

had been discharged at very close quarters. There was only the one pistol found in the

room, two barrels of which had been emptied. Mr. Hilton Cubitt had been shot through the

heart. It was equally conceivable that he had shot her and then himself, or that she had

been the criminal, for the revolver lay upon the floor midway between them.

“Has he been moved?” asked Holmes. “Has he been moved?” asked Holmes.

“We have moved nothing except the lady. We could not

leave her lying wounded upon the floor.” “We have moved nothing except the lady. We could not

leave her lying wounded upon the floor.”

“How long have you been here, Doctor?” “How long have you been here, Doctor?”

“Since four o’clock.” “Since four o’clock.”

“Anyone else?” “Anyone else?”

“Yes, the constable here.” “Yes, the constable here.”

“And you have touched nothing?” “And you have touched nothing?”

“Nothing.” “Nothing.”

“You have acted with great discretion. Who sent for

you?” “You have acted with great discretion. Who sent for

you?”

“The housemaid, Saunders.” “The housemaid, Saunders.”

“Was it she who gave the alarm?” “Was it she who gave the alarm?”

“She and Mrs. King, the cook.” “She and Mrs. King, the cook.”

“Where are they now?” “Where are they now?”

“In the kitchen, I believe.” “In the kitchen, I believe.”

“Then I think we had better hear their story at

once.” “Then I think we had better hear their story at

once.”

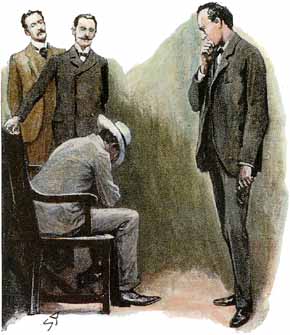

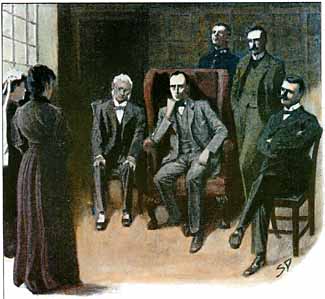

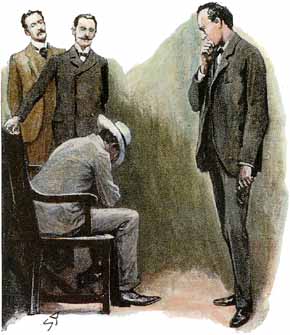

The old hall, oak-panelled and high-windowed, had been turned

into a court of investigation. Holmes sat in a great, old-fashioned chair, his inexorable

eyes gleaming out of his haggard face. I could read in them a set purpose to devote his

life to this quest until the client whom he had failed to save should at last be [519] avenged. The trim Inspector Martin,

the old, gray-headed country doctor, myself, and a stolid village policeman made up the

rest of that strange company. The old hall, oak-panelled and high-windowed, had been turned

into a court of investigation. Holmes sat in a great, old-fashioned chair, his inexorable

eyes gleaming out of his haggard face. I could read in them a set purpose to devote his

life to this quest until the client whom he had failed to save should at last be [519] avenged. The trim Inspector Martin,

the old, gray-headed country doctor, myself, and a stolid village policeman made up the

rest of that strange company.

The two women told their story clearly enough. They had been

aroused from their sleep by the sound of an explosion, which had been followed a minute

later by a second one. They slept in adjoining rooms, and Mrs. King had rushed in to

Saunders. Together they had descended the stairs. The door of the study was open, and a

candle was burning upon the table. Their master lay upon his face in the centre of the

room. He was quite dead. Near the window his wife was crouching, her head leaning against

the wall. She was horribly wounded, and the side of her face was red with blood. She

breathed heavily, but was incapable of saying anything. The passage, as well as the room,

was full of smoke and the smell of powder. The window was certainly shut and fastened upon

the inside. Both women were positive upon the point. They had at once sent for the doctor

and for the constable. Then, with the aid of the groom and the stable-boy, they had

conveyed their injured mistress to her room. Both she and her husband had occupied the

bed. She was clad in her dress–he in his dressing-gown, over his night-clothes.

Nothing had been moved in the study. So far as they knew, there had never been any quarrel

between husband and wife. They had always looked upon them as a very united couple. The two women told their story clearly enough. They had been

aroused from their sleep by the sound of an explosion, which had been followed a minute

later by a second one. They slept in adjoining rooms, and Mrs. King had rushed in to

Saunders. Together they had descended the stairs. The door of the study was open, and a

candle was burning upon the table. Their master lay upon his face in the centre of the

room. He was quite dead. Near the window his wife was crouching, her head leaning against

the wall. She was horribly wounded, and the side of her face was red with blood. She

breathed heavily, but was incapable of saying anything. The passage, as well as the room,

was full of smoke and the smell of powder. The window was certainly shut and fastened upon

the inside. Both women were positive upon the point. They had at once sent for the doctor

and for the constable. Then, with the aid of the groom and the stable-boy, they had

conveyed their injured mistress to her room. Both she and her husband had occupied the

bed. She was clad in her dress–he in his dressing-gown, over his night-clothes.

Nothing had been moved in the study. So far as they knew, there had never been any quarrel

between husband and wife. They had always looked upon them as a very united couple.

These were the main points of the servants’ evidence.

In answer to Inspector Martin, they were clear that every door was fastened upon the

inside, and that no one could have escaped from the house. In answer to Holmes, they both

remembered that they were conscious of the smell of powder from the moment that they ran

out of their rooms upon the top floor. “I commend that fact very carefully to your

attention,” said Holmes to his professional colleague. “And now I think that we

are in a position to undertake a thorough examination of the room.” These were the main points of the servants’ evidence.

In answer to Inspector Martin, they were clear that every door was fastened upon the

inside, and that no one could have escaped from the house. In answer to Holmes, they both

remembered that they were conscious of the smell of powder from the moment that they ran

out of their rooms upon the top floor. “I commend that fact very carefully to your

attention,” said Holmes to his professional colleague. “And now I think that we

are in a position to undertake a thorough examination of the room.”

The study proved to be a small chamber, lined on three sides

with books, and with a writing-table facing an ordinary window, which looked out upon the

garden. Our first attention was given to the body of the unfortunate squire, whose huge

frame lay stretched across the room. His disordered dress showed that he had been hastily

aroused from sleep. The bullet had been fired at him from the front, and had remained in

his body, after penetrating the heart. His death had certainly been instantaneous and

painless. There was no powder-marking either upon his dressing-gown or on his hands.

According to the country surgeon, the lady had stains upon her face, but none upon her

hand. The study proved to be a small chamber, lined on three sides

with books, and with a writing-table facing an ordinary window, which looked out upon the

garden. Our first attention was given to the body of the unfortunate squire, whose huge

frame lay stretched across the room. His disordered dress showed that he had been hastily

aroused from sleep. The bullet had been fired at him from the front, and had remained in

his body, after penetrating the heart. His death had certainly been instantaneous and

painless. There was no powder-marking either upon his dressing-gown or on his hands.

According to the country surgeon, the lady had stains upon her face, but none upon her

hand.

“The absence of the latter means nothing, though its

presence may mean everything,” said Holmes. “Unless the powder from a badly

fitting cartridge happens to spurt backward, one may fire many shots without leaving a

sign. I would suggest that Mr. Cubitt’s body may now be removed. I suppose, Doctor,

you have not recovered the bullet which wounded the lady?” “The absence of the latter means nothing, though its

presence may mean everything,” said Holmes. “Unless the powder from a badly

fitting cartridge happens to spurt backward, one may fire many shots without leaving a

sign. I would suggest that Mr. Cubitt’s body may now be removed. I suppose, Doctor,

you have not recovered the bullet which wounded the lady?”

“A serious operation will be necessary before that can be

done. But there are still four cartridges in the revolver. Two have been fired and two

wounds inflicted, so that each bullet can be accounted for.” “A serious operation will be necessary before that can be

done. But there are still four cartridges in the revolver. Two have been fired and two

wounds inflicted, so that each bullet can be accounted for.”

“So it would seem,” said Holmes. “Perhaps you

can account also for the bullet which has so obviously struck the edge of the

window?” “So it would seem,” said Holmes. “Perhaps you

can account also for the bullet which has so obviously struck the edge of the

window?”

He had turned suddenly, and his long, thin finger was pointing

to a hole which had been drilled right through the lower window-sash, about an inch above

the bottom. He had turned suddenly, and his long, thin finger was pointing

to a hole which had been drilled right through the lower window-sash, about an inch above

the bottom.

“By George!” cried the inspector. “How ever did

you see that?” “By George!” cried the inspector. “How ever did

you see that?”

“Because I looked for it.” “Because I looked for it.”

[520] “Wonderful!”

said the country doctor. “You are certainly right, sir. Then a third shot has been

fired, and therefore a third person must have been present. But who could that have been,

and how could he have got away?” [520] “Wonderful!”

said the country doctor. “You are certainly right, sir. Then a third shot has been

fired, and therefore a third person must have been present. But who could that have been,

and how could he have got away?”

“That is the problem which we are now about to

solve,” said Sherlock Holmes. “You remember, Inspector Martin, when the servants

said that on leaving their room they were at once conscious of a smell of powder, I

remarked that the point was an extremely important one?” “That is the problem which we are now about to

solve,” said Sherlock Holmes. “You remember, Inspector Martin, when the servants

said that on leaving their room they were at once conscious of a smell of powder, I

remarked that the point was an extremely important one?”

“Yes, sir; but I confess I did not quite follow

you.” “Yes, sir; but I confess I did not quite follow

you.”

“It suggested that at the time of the firing, the window

as well as the door of the room had been open. Otherwise the fumes of powder could not

have been blown so rapidly through the house. A draught in the room was necessary for

that. Both door and window were only open for a very short time, however.” “It suggested that at the time of the firing, the window

as well as the door of the room had been open. Otherwise the fumes of powder could not

have been blown so rapidly through the house. A draught in the room was necessary for

that. Both door and window were only open for a very short time, however.”

“How do you prove that?” “How do you prove that?”

“Because the candle was not guttered.” “Because the candle was not guttered.”

“Capital!” cried the inspector. “Capital!” “Capital!” cried the inspector. “Capital!”

“Feeling sure that the window had been open at the time

of the tragedy, I conceived that there might have been a third person in the affair, who

stood outside this opening and fired through it. Any shot directed at this person might

hit the sash. I looked, and there, sure enough, was the bullet mark!” “Feeling sure that the window had been open at the time

of the tragedy, I conceived that there might have been a third person in the affair, who

stood outside this opening and fired through it. Any shot directed at this person might

hit the sash. I looked, and there, sure enough, was the bullet mark!”

“But how came the window to be shut and fastened?” “But how came the window to be shut and fastened?”

“The woman’s first instinct would be to shut and

fasten the window. But, halloa! what is this?” “The woman’s first instinct would be to shut and

fasten the window. But, halloa! what is this?”

It was a lady’s hand-bag which stood upon the study

table–a trim little hand-bag of crocodile-skin and silver. Holmes opened it and

turned the contents out. There were twenty fifty-pound notes of the Bank of England, held

together by an india-rubber band–nothing else. It was a lady’s hand-bag which stood upon the study

table–a trim little hand-bag of crocodile-skin and silver. Holmes opened it and

turned the contents out. There were twenty fifty-pound notes of the Bank of England, held

together by an india-rubber band–nothing else.

“This must be preserved, for it will figure in the

trial,” said Holmes, as he handed the bag with its contents to the inspector.

“It is now necessary that we should try to throw some light upon this third bullet,

which has clearly, from the splintering of the wood, been fired from inside the room. I

should like to see Mrs. King, the cook, again. You said, Mrs. King, that you were awakened

by a loud explosion. When you said that, did you mean that it seemed to you to be louder

than the second one?” “This must be preserved, for it will figure in the

trial,” said Holmes, as he handed the bag with its contents to the inspector.

“It is now necessary that we should try to throw some light upon this third bullet,

which has clearly, from the splintering of the wood, been fired from inside the room. I

should like to see Mrs. King, the cook, again. You said, Mrs. King, that you were awakened

by a loud explosion. When you said that, did you mean that it seemed to you to be louder

than the second one?”

“Well, sir, it wakened me from my sleep, so it is hard to

judge. But it did seem very loud.” “Well, sir, it wakened me from my sleep, so it is hard to

judge. But it did seem very loud.”

“You don’t think that it might have been two shots

fired almost at the same instant?” “You don’t think that it might have been two shots

fired almost at the same instant?”

“I am sure I couldn’t say, sir.” “I am sure I couldn’t say, sir.”

“I believe that it was undoubtedly so. I rather think,

Inspector Martin, that we have now exhausted all that this room can teach us. If you will

kindly step round with me, we shall see what fresh evidence the garden has to offer.” “I believe that it was undoubtedly so. I rather think,

Inspector Martin, that we have now exhausted all that this room can teach us. If you will

kindly step round with me, we shall see what fresh evidence the garden has to offer.”

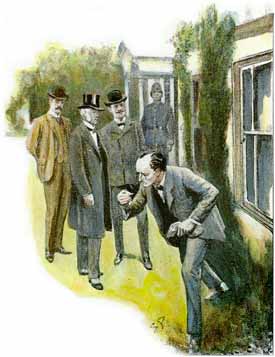

A flower-bed extended up to the study window, and we all broke

into an exclamation as we approached it. The flowers were trampled down, and the soft soil

was imprinted all over with footmarks. Large, masculine feet they were, with peculiarly

long, sharp toes. Holmes hunted about among the grass and leaves like a retriever after a

wounded bird. Then, with a cry of satisfaction, he bent forward and picked up a little

brazen cylinder. A flower-bed extended up to the study window, and we all broke

into an exclamation as we approached it. The flowers were trampled down, and the soft soil

was imprinted all over with footmarks. Large, masculine feet they were, with peculiarly

long, sharp toes. Holmes hunted about among the grass and leaves like a retriever after a

wounded bird. Then, with a cry of satisfaction, he bent forward and picked up a little

brazen cylinder.

“I thought so,” said he; “the revolver had

an ejector, and here is the third cartridge. I really think, Inspector Martin, that our

case is almost complete.” “I thought so,” said he; “the revolver had

an ejector, and here is the third cartridge. I really think, Inspector Martin, that our

case is almost complete.”

[521] The

country inspector’s face had shown his intense amazement at the rapid and masterful

progress of Holmes’s investigation. At first he had shown some disposition to assert

his own position, but now he was overcome with admiration, and ready to follow without

question wherever Holmes led. [521] The

country inspector’s face had shown his intense amazement at the rapid and masterful

progress of Holmes’s investigation. At first he had shown some disposition to assert

his own position, but now he was overcome with admiration, and ready to follow without

question wherever Holmes led.

“Whom do you suspect?” he asked. “Whom do you suspect?” he asked.

“I’ll go into that later. There are several points

in this problem which I have not been able to explain to you yet. Now that I have got so

far, I had best proceed on my own lines, and then clear the whole matter up once and for

all.” “I’ll go into that later. There are several points

in this problem which I have not been able to explain to you yet. Now that I have got so

far, I had best proceed on my own lines, and then clear the whole matter up once and for

all.”

“Just as you wish, Mr. Holmes, so long as we get our

man.” “Just as you wish, Mr. Holmes, so long as we get our

man.”

“I have no desire to make mysteries, but it is impossible

at the moment of action to enter into long and complex explanations. I have the threads of

this affair all in my hand. Even if this lady should never recover consciousness, we can

still reconstruct the events of last night, and insure that justice be done. First of all,

I wish to know whether there is any inn in this neighbourhood known as

‘Elrige’s’?” “I have no desire to make mysteries, but it is impossible

at the moment of action to enter into long and complex explanations. I have the threads of

this affair all in my hand. Even if this lady should never recover consciousness, we can

still reconstruct the events of last night, and insure that justice be done. First of all,

I wish to know whether there is any inn in this neighbourhood known as

‘Elrige’s’?”

The servants were cross-questioned, but none of them had heard

of such a place. The stable-boy threw a light upon the matter by remembering that a farmer

of that name lived some miles off, in the direction of East Ruston. The servants were cross-questioned, but none of them had heard

of such a place. The stable-boy threw a light upon the matter by remembering that a farmer

of that name lived some miles off, in the direction of East Ruston.

“Is it a lonely farm?” “Is it a lonely farm?”

“Very lonely, sir.” “Very lonely, sir.”

“Perhaps they have not heard yet of all that happened

here during the night?” “Perhaps they have not heard yet of all that happened

here during the night?”

“Maybe not, sir.” “Maybe not, sir.”

Holmes thought for a little, and then a curious smile played

over his face. Holmes thought for a little, and then a curious smile played

over his face.

“Saddle a horse, my lad,” said he. “I shall

wish you to take a note to Elrige’s Farm.” “Saddle a horse, my lad,” said he. “I shall

wish you to take a note to Elrige’s Farm.”

He took from his pocket the various slips of the dancing men.

With these in front of him, he worked for some time at the study-table. Finally he handed

a note to the boy, with directions to put it into the hands of the person to whom it was

addressed, and especially to answer no questions of any sort which might be put to him. I

saw the outside of the note, addressed in straggling, irregular characters, very unlike

Holmes’s usual precise hand. It was consigned to Mr. Abe Slaney, Elrige’s Farm,

East Ruston, Norfolk. He took from his pocket the various slips of the dancing men.

With these in front of him, he worked for some time at the study-table. Finally he handed

a note to the boy, with directions to put it into the hands of the person to whom it was

addressed, and especially to answer no questions of any sort which might be put to him. I

saw the outside of the note, addressed in straggling, irregular characters, very unlike

Holmes’s usual precise hand. It was consigned to Mr. Abe Slaney, Elrige’s Farm,

East Ruston, Norfolk.

“I think, Inspector,” Holmes remarked, “that

you would do well to telegraph for an escort, as, if my calculations prove to be correct,

you may have a particularly dangerous prisoner to convey to the county jail. The boy who

takes this note could no doubt forward your telegram. If there is an afternoon train to

town, Watson, I think we should do well to take it, as I have a chemical analysis of some

interest to finish, and this investigation draws rapidly to a close.” “I think, Inspector,” Holmes remarked, “that

you would do well to telegraph for an escort, as, if my calculations prove to be correct,

you may have a particularly dangerous prisoner to convey to the county jail. The boy who

takes this note could no doubt forward your telegram. If there is an afternoon train to

town, Watson, I think we should do well to take it, as I have a chemical analysis of some

interest to finish, and this investigation draws rapidly to a close.”

When the youth had been dispatched with the note, Sherlock

Holmes gave his instructions to the servants. If any visitor were to call asking for Mrs.

Hilton Cubitt, no information should be given as to her condition, but he was to be shown

at once into the drawing-room. He impressed these points upon them with the utmost

earnestness. Finally he led the way into the drawing-room, with the remark that the

business was now out of our hands, and that we must while away the time as best we might

until we could see what was in store for us. The doctor had departed to his patients, and

only the inspector and myself remained. When the youth had been dispatched with the note, Sherlock

Holmes gave his instructions to the servants. If any visitor were to call asking for Mrs.

Hilton Cubitt, no information should be given as to her condition, but he was to be shown

at once into the drawing-room. He impressed these points upon them with the utmost

earnestness. Finally he led the way into the drawing-room, with the remark that the

business was now out of our hands, and that we must while away the time as best we might

until we could see what was in store for us. The doctor had departed to his patients, and

only the inspector and myself remained.

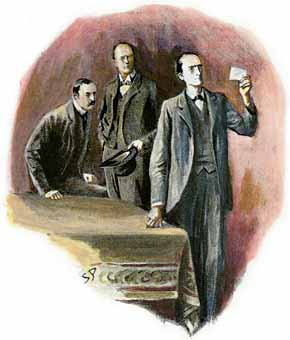

“I think that I can help you to pass an hour in an

interesting and profitable manner,” said Holmes, drawing his chair up to the table,

and spreading out in front of him the various papers upon which were recorded the antics

of the dancing men. “As to you, friend Watson, I owe you every atonement for having

allowed your [522] natural

curiosity to remain so long unsatisfied. To you, Inspector, the whole incident may appeal

as a remarkable professional study. I must tell you, first of all, the interesting

circumstances connected with the previous consultations which Mr. Hilton Cubitt has had

with me in Baker Street.” He then shortly recapitulated the facts which have already

been recorded. “I have here in front of me these singular productions, at which one

might smile, had they not proved themselves to be the forerunners of so terrible a

tragedy. I am fairly familiar with all forms of secret writings, and am myself the author

of a trifling monograph upon the subject, in which I analyze one hundred and sixty

separate ciphers, but I confess that this is entirely new to me. The object of those who

invented the system has apparently been to conceal that these characters convey a message,

and to give the idea that they are the mere random sketches of children. “I think that I can help you to pass an hour in an

interesting and profitable manner,” said Holmes, drawing his chair up to the table,

and spreading out in front of him the various papers upon which were recorded the antics

of the dancing men. “As to you, friend Watson, I owe you every atonement for having

allowed your [522] natural

curiosity to remain so long unsatisfied. To you, Inspector, the whole incident may appeal

as a remarkable professional study. I must tell you, first of all, the interesting

circumstances connected with the previous consultations which Mr. Hilton Cubitt has had

with me in Baker Street.” He then shortly recapitulated the facts which have already

been recorded. “I have here in front of me these singular productions, at which one

might smile, had they not proved themselves to be the forerunners of so terrible a

tragedy. I am fairly familiar with all forms of secret writings, and am myself the author

of a trifling monograph upon the subject, in which I analyze one hundred and sixty

separate ciphers, but I confess that this is entirely new to me. The object of those who

invented the system has apparently been to conceal that these characters convey a message,

and to give the idea that they are the mere random sketches of children.

“Having once recognized, however, that the symbols stood

for letters, and having applied the rules which guide us in all forms of secret writings,

the solution was easy enough. The first message submitted to me was so short that it was

impossible for me to do more than to say, with some confidence, that the symbol “Having once recognized, however, that the symbols stood

for letters, and having applied the rules which guide us in all forms of secret writings,

the solution was easy enough. The first message submitted to me was so short that it was

impossible for me to do more than to say, with some confidence, that the symbol  stood for E. As you are aware, E is the most common

letter in the English alphabet, and it predominates to so marked an extent that even in a

short sentence one would expect to find it most often. Out of fifteen symbols in the first

message, four were the same, so it was reasonable to set this down as E. It is true that

in some cases the figure was bearing a flag, and in some cases not, but it was probable,

from the way in which the flags were distributed, that they were used to break the

sentence up into words. I accepted this as a hypothesis, and noted that E was represented

by stood for E. As you are aware, E is the most common

letter in the English alphabet, and it predominates to so marked an extent that even in a

short sentence one would expect to find it most often. Out of fifteen symbols in the first

message, four were the same, so it was reasonable to set this down as E. It is true that

in some cases the figure was bearing a flag, and in some cases not, but it was probable,

from the way in which the flags were distributed, that they were used to break the

sentence up into words. I accepted this as a hypothesis, and noted that E was represented

by

“But now came the real difficulty of the inquiry. The

order of the English letters after E is by no means well marked, and any preponderance

which may be shown in an average of a printed sheet may be reversed in a single short

sentence. Speaking roughly, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, and L are the numerical order in

which letters occur; but T, A, O, and I are very nearly abreast of each other, and it

would be an endless task to try each combination until a meaning was arrived at. I

therefore waited for fresh material. In my second interview with Mr. Hilton Cubitt he was

able to give me two other short sentences and one message, which appeared–since there

was no flag–to be a single word. Here are the symbols: “But now came the real difficulty of the inquiry. The

order of the English letters after E is by no means well marked, and any preponderance

which may be shown in an average of a printed sheet may be reversed in a single short

sentence. Speaking roughly, T, A, O, I, N, S, H, R, D, and L are the numerical order in

which letters occur; but T, A, O, and I are very nearly abreast of each other, and it

would be an endless task to try each combination until a meaning was arrived at. I

therefore waited for fresh material. In my second interview with Mr. Hilton Cubitt he was

able to give me two other short sentences and one message, which appeared–since there

was no flag–to be a single word. Here are the symbols:

Now, in the single word I have already got the two E’s coming second and fourth in

a word of five letters. It might be ‘sever,’ or ‘lever,’ or

‘never.’ There can be no question that the latter as a reply to an appeal is far

the most probable, and the circumstances pointed to its being a reply written by the lady.

Accepting it as correct, we are now able to say that the symbols

stand respectively for N, V, and R.

“Even now I was in considerable difficulty, but a happy

thought put me in possession of several other letters. It occurred to me that if these

appeals came, as I expected, from someone who had been intimate with the lady in her early

life, a combination which contained two E’s with three letters between might very

well stand for the name ‘ELSIE.’ On examination I found that such a combination

formed the termination of the message which was three times repeated. It was certainly

some appeal to ‘Elsie.’ In this way I had got my L, S, and I. But what appeal

could it be? There were only four letters in the word which preceded ‘Elsie,’

and it ended in E. Surely the word must be ‘COME.’ I tried all other four

letters ending [523] in E,

but could find none to fit the case. So now I was in possession of C, O, and M, and I was

in a position to attack the first message once more, dividing it into words and putting

dots for each symbol which was still unknown. So treated, it worked out in this fashion: “Even now I was in considerable difficulty, but a happy

thought put me in possession of several other letters. It occurred to me that if these

appeals came, as I expected, from someone who had been intimate with the lady in her early

life, a combination which contained two E’s with three letters between might very

well stand for the name ‘ELSIE.’ On examination I found that such a combination

formed the termination of the message which was three times repeated. It was certainly

some appeal to ‘Elsie.’ In this way I had got my L, S, and I. But what appeal

could it be? There were only four letters in the word which preceded ‘Elsie,’

and it ended in E. Surely the word must be ‘COME.’ I tried all other four

letters ending [523] in E,

but could find none to fit the case. So now I was in possession of C, O, and M, and I was

in a position to attack the first message once more, dividing it into words and putting

dots for each symbol which was still unknown. So treated, it worked out in this fashion:

. M . ERE . ERE . . E . . E SL . NE. SL . NE.

“Now the first letter can only be A, which is

a most useful discovery, since it occurs no fewer than three times in this short sentence,

and the H is also apparent in the second word. Now it becomes: “Now the first letter can only be A, which is

a most useful discovery, since it occurs no fewer than three times in this short sentence,

and the H is also apparent in the second word. Now it becomes:

AM HERE HERE A . E A . E SLANE. SLANE.

Or, filling in the obvious vacancies in the name:

AM HERE HERE ABE ABE SLANEY. SLANEY.

I had so many letters now that I could proceed with considerable confidence to the

second message, which worked out in this fashion:

A . A . ELRI . ES. Here I could only

make sense by putting T and G for the missing letters, and supposing that the name was

that of some house or inn at which the writer was staying.” ELRI . ES. Here I could only

make sense by putting T and G for the missing letters, and supposing that the name was

that of some house or inn at which the writer was staying.”

Inspector Martin and I had listened with the utmost interest

to the full and clear account of how my friend had produced results which had led to so

complete a command over our difficulties. Inspector Martin and I had listened with the utmost interest

to the full and clear account of how my friend had produced results which had led to so

complete a command over our difficulties.

“What did you do then, sir?” asked the inspector. “What did you do then, sir?” asked the inspector.

“I had every reason to suppose that this Abe Slaney was

an American, since Abe is an American contraction, and since a letter from America had

been the starting-point of all the trouble. I had also every cause to think that there was

some criminal secret in the matter. The lady’s allusions to her past, and her refusal

to take her husband into her confidence, both pointed in that direction. I therefore

cabled to my friend, Wilson Hargreave, of the New York Police Bureau, who has more than

once made use of my knowledge of London crime. I asked him whether the name of Abe Slaney

was known to him. Here is his reply: ‘The most dangerous crook in Chicago.’ On

the very evening upon which I had his answer, Hilton Cubitt sent me the last message from

Slaney. Working with known letters, it took this form: “I had every reason to suppose that this Abe Slaney was

an American, since Abe is an American contraction, and since a letter from America had

been the starting-point of all the trouble. I had also every cause to think that there was

some criminal secret in the matter. The lady’s allusions to her past, and her refusal

to take her husband into her confidence, both pointed in that direction. I therefore

cabled to my friend, Wilson Hargreave, of the New York Police Bureau, who has more than

once made use of my knowledge of London crime. I asked him whether the name of Abe Slaney

was known to him. Here is his reply: ‘The most dangerous crook in Chicago.’ On

the very evening upon which I had his answer, Hilton Cubitt sent me the last message from

Slaney. Working with known letters, it took this form:

ELSIE . RE . ARE . RE . ARE TO TO MEET MEET THY THY GO . GO .

The addition of a P and a D completed a message which showed me that the rascal was

proceeding from persuasion to threats, and my knowledge of the crooks of Chicago prepared

me to find that he might very rapidly put his words into action. I at once came to Norfolk

with my friend and colleague, Dr. Watson, but, unhappily, only in time to find that the

worst had already occurred.”

“It is a privilege to be associated with you in the

handling of a case,” said the inspector, warmly. “You will excuse me, however,

if I speak frankly to you. You are only answerable to yourself, but I have to answer to my