|

|

“It’s not an airy nothing, you see,” said he,

smiling. “On the contrary, it is solid enough for a man to break his hand over. Is

Mrs. Watson in?” “It’s not an airy nothing, you see,” said he,

smiling. “On the contrary, it is solid enough for a man to break his hand over. Is

Mrs. Watson in?”

“She is away upon a visit.” “She is away upon a visit.”

“Indeed! You are alone?” “Indeed! You are alone?”

“Quite.” “Quite.”

“Then it makes it the easier for me to propose that you

should come away with me for a week to the Continent.” “Then it makes it the easier for me to propose that you

should come away with me for a week to the Continent.”

“Where?” “Where?”

“Oh, anywhere. It’s all the same to me.” “Oh, anywhere. It’s all the same to me.”

There was something very strange in all this. It was not

Holmes’s nature to take an aimless holiday, and something about his pale, worn face

told me that his nerves were at their highest tension. He saw the question in my eyes,

and, putting his finger-tips together and his elbows upon his knees, he explained the

situation. There was something very strange in all this. It was not

Holmes’s nature to take an aimless holiday, and something about his pale, worn face

told me that his nerves were at their highest tension. He saw the question in my eyes,

and, putting his finger-tips together and his elbows upon his knees, he explained the

situation.

“You have probably never heard of Professor

Moriarty?” said he. “You have probably never heard of Professor

Moriarty?” said he.

“Never.” “Never.”

“Ay, there’s the genius and the wonder of the

thing!” he cried. “The man pervades London, and no one has heard of him.

That’s what puts him on a pinnacle in the records of crime. I tell you Watson, in all

seriousness, that if I could beat that man, if I could free society of him, I should feel

that my own career had reached its summit, and I should be prepared to turn to some more

placid line in life. Between ourselves, the recent cases in which I have been of

assistance to the royal family of Scandinavia, and to the French republic, have left me in

such a position that I could continue to live in the quiet fashion which is most congenial

to me, and to concentrate my attention upon my chemical researches. But I could not rest,

Watson, I could not sit quiet in my chair, if I thought that such a man as Professor

Moriarty were walking the streets of London unchallenged.” “Ay, there’s the genius and the wonder of the

thing!” he cried. “The man pervades London, and no one has heard of him.

That’s what puts him on a pinnacle in the records of crime. I tell you Watson, in all

seriousness, that if I could beat that man, if I could free society of him, I should feel

that my own career had reached its summit, and I should be prepared to turn to some more

placid line in life. Between ourselves, the recent cases in which I have been of

assistance to the royal family of Scandinavia, and to the French republic, have left me in

such a position that I could continue to live in the quiet fashion which is most congenial

to me, and to concentrate my attention upon my chemical researches. But I could not rest,

Watson, I could not sit quiet in my chair, if I thought that such a man as Professor

Moriarty were walking the streets of London unchallenged.”

“What has he done, then?” “What has he done, then?”

“His career has been an extraordinary one. He is a man of

good birth and excellent education, endowed by nature with a phenomenal mathematical

faculty. At the age of twenty-one he wrote a treatise upon the binomial theorem, which has

had a European vogue. On the strength of it he won the mathematical chair at one of our

smaller universities, and had, to all appearances, a most brilliant career before him. But

the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical [471] kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which,

instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his

extraordinary mental powers. Dark rumours gathered round him in the university town, and

eventually he was compelled to resign his chair and to come down to London, where he set

up as an army coach. So much is known to the world, but what I am telling you now is what

I have myself discovered. “His career has been an extraordinary one. He is a man of

good birth and excellent education, endowed by nature with a phenomenal mathematical

faculty. At the age of twenty-one he wrote a treatise upon the binomial theorem, which has

had a European vogue. On the strength of it he won the mathematical chair at one of our

smaller universities, and had, to all appearances, a most brilliant career before him. But

the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical [471] kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which,

instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his

extraordinary mental powers. Dark rumours gathered round him in the university town, and

eventually he was compelled to resign his chair and to come down to London, where he set

up as an army coach. So much is known to the world, but what I am telling you now is what

I have myself discovered.

“As you are aware, Watson, there is no one who knows the

higher criminal world of London so well as I do. For years past I have continually been

conscious of some power behind the malefactor, some deep organizing power which forever

stands in the way of the law, and throws its shield over the wrong-doer. Again and again

in cases of the most varying sorts–forgery cases, robberies, murders–I have felt

the presence of this force, and I have deduced its action in many of those undiscovered

crimes in which I have not been personally consulted. For years I have endeavoured to

break through the veil which shrouded it, and at last the time came when I seized my

thread and followed it, until it led me, after a thousand cunning windings, to

ex-Professor Moriarty, of mathematical celebrity. “As you are aware, Watson, there is no one who knows the

higher criminal world of London so well as I do. For years past I have continually been

conscious of some power behind the malefactor, some deep organizing power which forever

stands in the way of the law, and throws its shield over the wrong-doer. Again and again

in cases of the most varying sorts–forgery cases, robberies, murders–I have felt

the presence of this force, and I have deduced its action in many of those undiscovered

crimes in which I have not been personally consulted. For years I have endeavoured to

break through the veil which shrouded it, and at last the time came when I seized my

thread and followed it, until it led me, after a thousand cunning windings, to

ex-Professor Moriarty, of mathematical celebrity.

“He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer

of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a

genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits

motionless, like a spider in the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand

radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He

only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized. Is there a crime to be

done, a paper to be abstracted, we will say, a house to be rifled, a man to be

removed–the word is passed to the professor, the matter is organized and carried out.

The agent may be caught. In that case money is found for his bail or his defence. But the

central power which uses the agent is never caught–never so much as suspected. This

was the organization which I deduced, Watson, and which I devoted my whole energy to

exposing and breaking up. “He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer

of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a

genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits

motionless, like a spider in the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand

radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He

only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized. Is there a crime to be

done, a paper to be abstracted, we will say, a house to be rifled, a man to be

removed–the word is passed to the professor, the matter is organized and carried out.

The agent may be caught. In that case money is found for his bail or his defence. But the

central power which uses the agent is never caught–never so much as suspected. This

was the organization which I deduced, Watson, and which I devoted my whole energy to

exposing and breaking up.

“But the professor was fenced round with safeguards so

cunningly devised that, do what I would, it seemed impossible to get evidence which would

convict in a court of law. You know my powers, my dear Watson, and yet at the end of three

months I was forced to confess that I had at last met an antagonist who was my

intellectual equal. My horror at his crimes was lost in my admiration at his skill. But at

last he made a trip–only a little, little trip–but it was more than he could

afford, when I was so close upon him. I had my chance, and, starting from that point, I

have woven my net round him until now it is all ready to close. In three days–that is

to say, on Monday next–matters will be ripe, and the professor, with all the

principal members of his gang, will be in the hands of the police. Then will come the

greatest criminal trial of the century, the clearing up of over forty mysteries, and the

rope for all of them; but if we move at all prematurely, you understand, they may slip out

of our hands even at the last moment. “But the professor was fenced round with safeguards so

cunningly devised that, do what I would, it seemed impossible to get evidence which would

convict in a court of law. You know my powers, my dear Watson, and yet at the end of three

months I was forced to confess that I had at last met an antagonist who was my

intellectual equal. My horror at his crimes was lost in my admiration at his skill. But at

last he made a trip–only a little, little trip–but it was more than he could

afford, when I was so close upon him. I had my chance, and, starting from that point, I

have woven my net round him until now it is all ready to close. In three days–that is

to say, on Monday next–matters will be ripe, and the professor, with all the

principal members of his gang, will be in the hands of the police. Then will come the

greatest criminal trial of the century, the clearing up of over forty mysteries, and the

rope for all of them; but if we move at all prematurely, you understand, they may slip out

of our hands even at the last moment.

“Now, if I could have done this without the knowledge of

Professor Moriarty, all would have been well. But he was too wily for that. He saw every

step which I took to draw my toils round him. Again and again he strove to break away, but

I as often headed him off. I tell you, my friend, that if a detailed account of that

silent contest could be written, it would take its place as the most brilliant bit of

thrust-and-parry work in the history of detection. Never have I risen to such a height,

and never have I been so hard pressed by an opponent. He cut deep, and yet I just undercut

him. This morning the last steps were taken, and three days [472] only were wanted to complete the business. I was

sitting in my room thinking the matter over when the door opened and Professor Moriarty

stood before me. “Now, if I could have done this without the knowledge of

Professor Moriarty, all would have been well. But he was too wily for that. He saw every

step which I took to draw my toils round him. Again and again he strove to break away, but

I as often headed him off. I tell you, my friend, that if a detailed account of that

silent contest could be written, it would take its place as the most brilliant bit of

thrust-and-parry work in the history of detection. Never have I risen to such a height,

and never have I been so hard pressed by an opponent. He cut deep, and yet I just undercut

him. This morning the last steps were taken, and three days [472] only were wanted to complete the business. I was

sitting in my room thinking the matter over when the door opened and Professor Moriarty

stood before me.

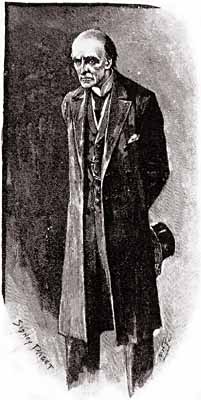

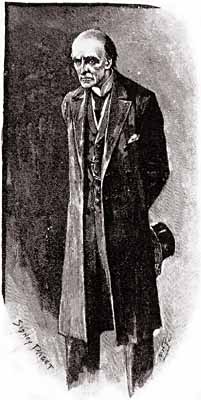

“My nerves are fairly proof, Watson, but I must

confess to a start when I saw the very man who had been so much in my thoughts standing

there on my threshold. His appearance was quite familiar to me. He is extremely tall and

thin, his forehead domes out in a white curve, and his two eyes are deeply sunken in his

head. He is clean-shaven, pale, and ascetic-looking, retaining something of the professor

in his features. His shoulders are rounded from much study, and his face protrudes forward

and is forever slowly oscillating from side to side in a curiously reptilian fashion. He

peered at me with great curiosity in his puckered eyes. “My nerves are fairly proof, Watson, but I must

confess to a start when I saw the very man who had been so much in my thoughts standing

there on my threshold. His appearance was quite familiar to me. He is extremely tall and

thin, his forehead domes out in a white curve, and his two eyes are deeply sunken in his

head. He is clean-shaven, pale, and ascetic-looking, retaining something of the professor

in his features. His shoulders are rounded from much study, and his face protrudes forward

and is forever slowly oscillating from side to side in a curiously reptilian fashion. He

peered at me with great curiosity in his puckered eyes.

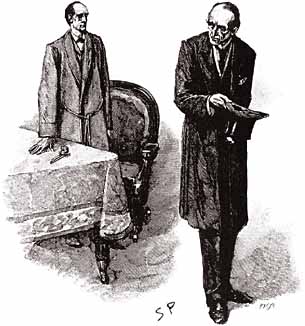

“ ‘You have less frontal development than I should

have expected,’ said he at last. ‘It is a dangerous habit to finger loaded

firearms in the pocket of one’s dressing-gown.’ “ ‘You have less frontal development than I should

have expected,’ said he at last. ‘It is a dangerous habit to finger loaded

firearms in the pocket of one’s dressing-gown.’

“The fact is that upon his entrance I had instantly

recognized the extreme personal danger in which I lay. The only conceivable escape for him

lay in silencing my tongue. In an instant I had slipped the revolver from the drawer into

my pocket and was covering him through the cloth. At his remark I drew the weapon out and

laid it cocked upon the table. He still smiled and blinked, but there was something about

his eyes which made me feel very glad that I had it there. “The fact is that upon his entrance I had instantly

recognized the extreme personal danger in which I lay. The only conceivable escape for him

lay in silencing my tongue. In an instant I had slipped the revolver from the drawer into

my pocket and was covering him through the cloth. At his remark I drew the weapon out and

laid it cocked upon the table. He still smiled and blinked, but there was something about

his eyes which made me feel very glad that I had it there.

“ ‘You evidently don’t know me,’ said he. “ ‘You evidently don’t know me,’ said he.

“ ‘On the contrary,’ I answered, ‘I think

it is fairly evident that I do. Pray take a chair. I can spare you five minutes if you

have anything to say.’ “ ‘On the contrary,’ I answered, ‘I think

it is fairly evident that I do. Pray take a chair. I can spare you five minutes if you

have anything to say.’

“ ‘All that I have to say has already crossed your

mind,’ said he. “ ‘All that I have to say has already crossed your

mind,’ said he.

“ ‘Then possibly my answer has crossed yours,’

I replied. “ ‘Then possibly my answer has crossed yours,’

I replied.

“ ‘You stand fast?’ “ ‘You stand fast?’

“ ‘Absolutely.’ “ ‘Absolutely.’

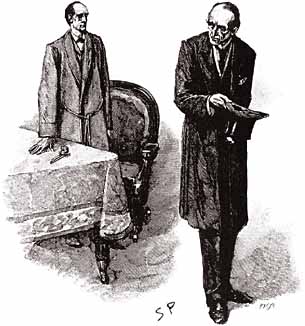

“He clapped his hand into his pocket, and I raised the

pistol from the table. But he merely drew out a memorandum-book in which he had scribbled

some dates. “He clapped his hand into his pocket, and I raised the

pistol from the table. But he merely drew out a memorandum-book in which he had scribbled

some dates.

“ ‘You crossed my path on the fourth of

January,’ said he. ‘On the twenty-third you incommoded me; by the middle of

February I was seriously inconvenienced by you; at the end of March I was absolutely

hampered in my plans; and now, at the close of April, I find myself placed in such a

position through your continual persecution that I am in positive danger of losing my

liberty. The situation is becoming an impossible one.’ “ ‘You crossed my path on the fourth of

January,’ said he. ‘On the twenty-third you incommoded me; by the middle of

February I was seriously inconvenienced by you; at the end of March I was absolutely

hampered in my plans; and now, at the close of April, I find myself placed in such a

position through your continual persecution that I am in positive danger of losing my

liberty. The situation is becoming an impossible one.’

“ ‘Have you any suggestion to make?’ I asked. “ ‘Have you any suggestion to make?’ I asked.

“ ‘You must drop it, Mr. Holmes,’ said he,

swaying his face about. ‘You really must, you know.’ “ ‘You must drop it, Mr. Holmes,’ said he,

swaying his face about. ‘You really must, you know.’

“ ‘After Monday,’ said I. “ ‘After Monday,’ said I.

“ ‘Tut, tut!’ said he. ‘I am quite sure

that a man of your intelligence will see that there can be but one outcome to this affair.

It is necessary that you should withdraw. You have worked things in such a fashion that we

have only one resource left. It has been an intellectual treat to me to see the way in

which you have grappled with this affair, and I say, unaffectedly, that it would be a

grief to me to be forced to take any extreme measure. You smile, sir, but I assure you

that it really would.’ “ ‘Tut, tut!’ said he. ‘I am quite sure

that a man of your intelligence will see that there can be but one outcome to this affair.

It is necessary that you should withdraw. You have worked things in such a fashion that we

have only one resource left. It has been an intellectual treat to me to see the way in

which you have grappled with this affair, and I say, unaffectedly, that it would be a

grief to me to be forced to take any extreme measure. You smile, sir, but I assure you

that it really would.’

“ ‘Danger is part of my trade,’ I remarked. “ ‘Danger is part of my trade,’ I remarked.

“ ‘This is not danger,’ said he. ‘It is

inevitable destruction. You stand in the way not merely of an individual but of a mighty

organization, the full extent of [473] which

you, with all your cleverness, have been unable to realize. You must stand clear, Mr.

Holmes, or be trodden under foot.’ “ ‘This is not danger,’ said he. ‘It is

inevitable destruction. You stand in the way not merely of an individual but of a mighty

organization, the full extent of [473] which

you, with all your cleverness, have been unable to realize. You must stand clear, Mr.

Holmes, or be trodden under foot.’

“ ‘I am afraid,’ said I, rising, ‘that in

the pleasure of this conversation I am neglecting business of importance which awaits me

elsewhere.’ “ ‘I am afraid,’ said I, rising, ‘that in

the pleasure of this conversation I am neglecting business of importance which awaits me

elsewhere.’

“He rose also and looked at me in silence, shaking his

head sadly. “He rose also and looked at me in silence, shaking his

head sadly.

“ ‘Well, well,’ said he at last. ‘It seems

a pity, but I have done what I could. I know every move of your game. You can do nothing

before Monday. It has been a duel between you and me, Mr. Holmes. You hope to place me in

the dock. I tell you that I will never stand in the dock. You hope to beat me. I tell you

that you will never beat me. If you are clever enough to bring destruction upon me, rest

assured that I shall do as much to you.’ “ ‘Well, well,’ said he at last. ‘It seems

a pity, but I have done what I could. I know every move of your game. You can do nothing

before Monday. It has been a duel between you and me, Mr. Holmes. You hope to place me in

the dock. I tell you that I will never stand in the dock. You hope to beat me. I tell you

that you will never beat me. If you are clever enough to bring destruction upon me, rest

assured that I shall do as much to you.’

“ ‘You have paid me several compliments, Mr.

Moriarty,’ said I. ‘Let me pay you one in return when I say that if I were

assured of the former eventuality I would, in the interests of the public, cheerfully

accept the latter.’ “ ‘You have paid me several compliments, Mr.

Moriarty,’ said I. ‘Let me pay you one in return when I say that if I were

assured of the former eventuality I would, in the interests of the public, cheerfully

accept the latter.’

“ ‘I can promise you the one, but not the

other,’ he snarled, and so turned his rounded back upon me and went peering and

blinking out of the room. “ ‘I can promise you the one, but not the

other,’ he snarled, and so turned his rounded back upon me and went peering and

blinking out of the room.

“That was my singular interview with Professor

Moriarty. I confess that it left an unpleasant effect upon my mind. His soft, precise

fashion of speech leaves a conviction of sincerity which a mere bully could not produce.

Of course, you will say: ‘Why not take police precautions against him?’ The

reason is that I am well convinced that it is from his agents the blow would fall. I have

the best of proofs that it would be so.” “That was my singular interview with Professor

Moriarty. I confess that it left an unpleasant effect upon my mind. His soft, precise

fashion of speech leaves a conviction of sincerity which a mere bully could not produce.

Of course, you will say: ‘Why not take police precautions against him?’ The

reason is that I am well convinced that it is from his agents the blow would fall. I have

the best of proofs that it would be so.”

“You have already been assaulted?” “You have already been assaulted?”

“My dear Watson, Professor Moriarty is not a man who lets

the grass grow under his feet. I went out about midday to transact some business in Oxford

Street. As I passed the corner which leads from Bentinck Street on to the Welbeck Street

crossing a two-horse van furiously driven whizzed round and was on me like a flash. I

sprang for the foot-path and saved myself by the fraction of a second. The van dashed

round by Marylebone Lane and was gone in an instant. I kept to the pavement after that,

Watson, but as I walked down Vere Street a brick came down from the roof of one of the

houses and was shattered to fragments at my feet. I called the police and had the place

examined. There were slates and bricks piled up on the roof preparatory to some repairs,

and they would have me believe that the wind had toppled over one of these. Of course I

knew better, but I could prove nothing. I took a cab after that and reached my

brother’s rooms in Pall Mall, where I spent the day. Now I have come round to you,

and on my way I was attacked by a rough with a bludgeon. I knocked him down, and the

police have him in custody; but I can tell you with the most absolute confidence that no

possible connection will ever be traced between the gentleman upon whose front teeth I

have barked my knuckles and the retiring mathematical coach, who is, I daresay, working

out problems upon a black-board ten miles away. You will not wonder, Watson, that my first

act on entering your rooms was to close your shutters, and that I have been compelled to

ask your permission to leave the house by some less conspicuous exit than the front

door.” “My dear Watson, Professor Moriarty is not a man who lets

the grass grow under his feet. I went out about midday to transact some business in Oxford

Street. As I passed the corner which leads from Bentinck Street on to the Welbeck Street

crossing a two-horse van furiously driven whizzed round and was on me like a flash. I

sprang for the foot-path and saved myself by the fraction of a second. The van dashed

round by Marylebone Lane and was gone in an instant. I kept to the pavement after that,

Watson, but as I walked down Vere Street a brick came down from the roof of one of the

houses and was shattered to fragments at my feet. I called the police and had the place

examined. There were slates and bricks piled up on the roof preparatory to some repairs,

and they would have me believe that the wind had toppled over one of these. Of course I

knew better, but I could prove nothing. I took a cab after that and reached my

brother’s rooms in Pall Mall, where I spent the day. Now I have come round to you,

and on my way I was attacked by a rough with a bludgeon. I knocked him down, and the

police have him in custody; but I can tell you with the most absolute confidence that no

possible connection will ever be traced between the gentleman upon whose front teeth I

have barked my knuckles and the retiring mathematical coach, who is, I daresay, working

out problems upon a black-board ten miles away. You will not wonder, Watson, that my first

act on entering your rooms was to close your shutters, and that I have been compelled to

ask your permission to leave the house by some less conspicuous exit than the front

door.”

I had often admired my friend’s courage, but never more

than now, as he sat quietly checking off a series of incidents which must have combined to

make up a day of horror. I had often admired my friend’s courage, but never more

than now, as he sat quietly checking off a series of incidents which must have combined to

make up a day of horror.

“You will spend the night here?” I said. “You will spend the night here?” I said.

“No, my friend, you might find me a dangerous guest. I

have my plans laid, [474] and

all will be well. Matters have gone so far now that they can move without my help as far

as the arrest goes, though my presence is necessary for a conviction. It is obvious,

therefore, that I cannot do better than get away for the few days which remain before the

police are at liberty to act. It would be a great pleasure to me, therefore, if you could

come on to the Continent with me.” “No, my friend, you might find me a dangerous guest. I

have my plans laid, [474] and

all will be well. Matters have gone so far now that they can move without my help as far

as the arrest goes, though my presence is necessary for a conviction. It is obvious,

therefore, that I cannot do better than get away for the few days which remain before the

police are at liberty to act. It would be a great pleasure to me, therefore, if you could

come on to the Continent with me.”

“The practice is quiet,” said I, “and I have an

accommodating neighbour. I should be glad to come.” “The practice is quiet,” said I, “and I have an

accommodating neighbour. I should be glad to come.”

“And to start to-morrow morning?” “And to start to-morrow morning?”

“If necessary.” “If necessary.”

“Oh, yes, it is most necessary. Then these are your

instructions, and I beg, my dear Watson, that you will obey them to the letter, for you

are now playing a double-handed game with me against the cleverest rogue and the most

powerful syndicate of criminals in Europe. Now listen! You will dispatch whatever luggage

you intend to take by a trusty messenger unaddressed to Victoria to-night. In the morning

you will send for a hansom, desiring your man to take neither the first nor the second

which may present itself. Into this hansom you will jump, and you will drive to the Strand

end of the Lowther Arcade, handing the address to the cabman upon a slip of paper, with a

request that he will not throw it away. Have your fare ready, and the instant that your

cab stops, dash through the Arcade, timing yourself to reach the other side at a

quarter-past nine. You will find a small brougham waiting close to the curb, driven by a

fellow with a heavy black cloak tipped at the collar with red. Into this you will step,

and you will reach Victoria in time for the Continental express.” “Oh, yes, it is most necessary. Then these are your

instructions, and I beg, my dear Watson, that you will obey them to the letter, for you

are now playing a double-handed game with me against the cleverest rogue and the most

powerful syndicate of criminals in Europe. Now listen! You will dispatch whatever luggage

you intend to take by a trusty messenger unaddressed to Victoria to-night. In the morning

you will send for a hansom, desiring your man to take neither the first nor the second

which may present itself. Into this hansom you will jump, and you will drive to the Strand

end of the Lowther Arcade, handing the address to the cabman upon a slip of paper, with a

request that he will not throw it away. Have your fare ready, and the instant that your

cab stops, dash through the Arcade, timing yourself to reach the other side at a

quarter-past nine. You will find a small brougham waiting close to the curb, driven by a

fellow with a heavy black cloak tipped at the collar with red. Into this you will step,

and you will reach Victoria in time for the Continental express.”

“Where shall I meet you?” “Where shall I meet you?”

“At the station. The second first-class carriage from the

front will be reserved for us.” “At the station. The second first-class carriage from the

front will be reserved for us.”

“The carriage is our rendezvous, then?” “The carriage is our rendezvous, then?”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

It was in vain that I asked Holmes to remain for the evening.

It was evident to me that he thought he might bring trouble to the roof he was under, and

that that was the motive which impelled him to go. With a few hurried words as to our

plans for the morrow he rose and came out with me into the garden, clambering over the

wall which leads into Mortimer Street, and immediately whistling for a hansom, in which I

heard him drive away. It was in vain that I asked Holmes to remain for the evening.

It was evident to me that he thought he might bring trouble to the roof he was under, and

that that was the motive which impelled him to go. With a few hurried words as to our

plans for the morrow he rose and came out with me into the garden, clambering over the

wall which leads into Mortimer Street, and immediately whistling for a hansom, in which I

heard him drive away.

In the morning I obeyed Holmes’s injunctions to the

letter. A hansom was procured with such precautions as would prevent its being one which

was placed ready for us, and I drove immediately after breakfast to the Lowther Arcade,

through which I hurried at the top of my speed. A brougham was waiting with a very massive

driver wrapped in a dark cloak, who, the instant that I had stepped in, whipped up the

horse and rattled off to Victoria Station. On my alighting there he turned the carriage,

and dashed away again without so much as a look in my direction. In the morning I obeyed Holmes’s injunctions to the

letter. A hansom was procured with such precautions as would prevent its being one which

was placed ready for us, and I drove immediately after breakfast to the Lowther Arcade,

through which I hurried at the top of my speed. A brougham was waiting with a very massive

driver wrapped in a dark cloak, who, the instant that I had stepped in, whipped up the

horse and rattled off to Victoria Station. On my alighting there he turned the carriage,

and dashed away again without so much as a look in my direction.

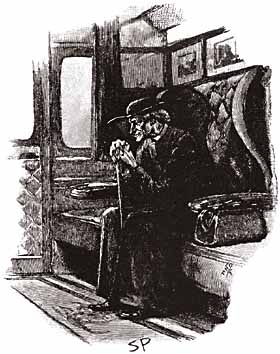

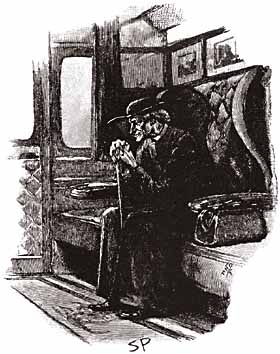

So far all had gone admirably. My luggage was waiting for me,

and I had no difficulty in finding the carriage which Holmes had indicated, the less so as

it was the only one in the train which was marked “Engaged.” My only source of

anxiety now was the non-appearance of Holmes. The station clock marked only seven minutes

from the time when we were due to start. In vain I searched among the groups of travellers

and leave-takers for the lithe figure of my friend. There was no sign of him. I spent a

few minutes in assisting a venerable Italian priest, who was endeavouring to make a porter

understand, in his broken English, that his luggage [475] was to be booked through to Paris. Then, having taken

another look round, I returned to my carriage, where I found that the porter, in spite of

the ticket, had given me my decrepit Italian friend as a travelling companion. It was

useless for me to explain to him that his presence was an intrusion, for my Italian was

even more limited than his English, so I shrugged my shoulders resignedly, and continued

to look out anxiously for my friend. A chill of fear had come over me, as I thought that

his absence might mean that some blow had fallen during the night. Already the doors had

all been shut and the whistle blown, when– – So far all had gone admirably. My luggage was waiting for me,

and I had no difficulty in finding the carriage which Holmes had indicated, the less so as

it was the only one in the train which was marked “Engaged.” My only source of

anxiety now was the non-appearance of Holmes. The station clock marked only seven minutes

from the time when we were due to start. In vain I searched among the groups of travellers

and leave-takers for the lithe figure of my friend. There was no sign of him. I spent a

few minutes in assisting a venerable Italian priest, who was endeavouring to make a porter

understand, in his broken English, that his luggage [475] was to be booked through to Paris. Then, having taken

another look round, I returned to my carriage, where I found that the porter, in spite of

the ticket, had given me my decrepit Italian friend as a travelling companion. It was

useless for me to explain to him that his presence was an intrusion, for my Italian was

even more limited than his English, so I shrugged my shoulders resignedly, and continued

to look out anxiously for my friend. A chill of fear had come over me, as I thought that

his absence might mean that some blow had fallen during the night. Already the doors had

all been shut and the whistle blown, when– –

“My dear Watson,” said a voice, “you have

not even condescended to say good-morning.” “My dear Watson,” said a voice, “you have

not even condescended to say good-morning.”

I turned in uncontrollable astonishment. The aged ecclesiastic

had turned his face towards me. For an instant the wrinkles were smoothed away, the nose

drew away from the chin, the lower lip ceased to protrude and the mouth to mumble, the

dull eyes regained their fire, the drooping figure expanded. The next the whole frame

collapsed again, and Holmes had gone as quickly as he had come. I turned in uncontrollable astonishment. The aged ecclesiastic

had turned his face towards me. For an instant the wrinkles were smoothed away, the nose

drew away from the chin, the lower lip ceased to protrude and the mouth to mumble, the

dull eyes regained their fire, the drooping figure expanded. The next the whole frame

collapsed again, and Holmes had gone as quickly as he had come.

“Good heavens!” I cried, “how you startled

me!” “Good heavens!” I cried, “how you startled

me!”

“Every precaution is still necessary,” he whispered.

“I have reason to think that they are hot upon our trail. Ah, there is Moriarty

himself.” “Every precaution is still necessary,” he whispered.

“I have reason to think that they are hot upon our trail. Ah, there is Moriarty

himself.”

The train had already begun to move as Holmes spoke. Glancing

back, I saw a tall man pushing his way furiously through the crowd, and waving his hand as

if he desired to have the train stopped. It was too late, however, for we were rapidly

gathering momentum, and an instant later had shot clear of the station. The train had already begun to move as Holmes spoke. Glancing

back, I saw a tall man pushing his way furiously through the crowd, and waving his hand as

if he desired to have the train stopped. It was too late, however, for we were rapidly

gathering momentum, and an instant later had shot clear of the station.

“With all our precautions, you see that we have cut it

rather fine,” said Holmes, laughing. He rose, and throwing off the black cassock and

hat which had formed his disguise, he packed them away in a hand-bag. “With all our precautions, you see that we have cut it

rather fine,” said Holmes, laughing. He rose, and throwing off the black cassock and

hat which had formed his disguise, he packed them away in a hand-bag.

“Have you seen the morning paper, Watson?” “Have you seen the morning paper, Watson?”

“No.” “No.”

“You haven’t seen about Baker Street, then?” “You haven’t seen about Baker Street, then?”

“Baker Street?” “Baker Street?”

“They set fire to our rooms last night. No great harm was

done.” “They set fire to our rooms last night. No great harm was

done.”

“Good heavens, Holmes, this is intolerable!” “Good heavens, Holmes, this is intolerable!”

“They must have lost my track completely after their

bludgeonman was arrested. Otherwise they could not have imagined that I had returned to my

rooms. They have evidently taken the precaution of watching you, however, and that is what

has brought Moriarty to Victoria. You could not have made any slip in coming?” “They must have lost my track completely after their

bludgeonman was arrested. Otherwise they could not have imagined that I had returned to my

rooms. They have evidently taken the precaution of watching you, however, and that is what

has brought Moriarty to Victoria. You could not have made any slip in coming?”

“I did exactly what you advised.” “I did exactly what you advised.”

“Did you find your brougham?” “Did you find your brougham?”

“Yes, it was waiting.” “Yes, it was waiting.”

“Did you recognize your coachman?” “Did you recognize your coachman?”

“No.” “No.”

“It was my brother Mycroft. It is an advantage to get

about in such a case without taking a mercenary into your confidence. But we must plan

what we are to do about Moriarty now.” “It was my brother Mycroft. It is an advantage to get

about in such a case without taking a mercenary into your confidence. But we must plan

what we are to do about Moriarty now.”

“As this is an express, and as the boat runs in

connection with it, I should think we have shaken him off very effectively.” “As this is an express, and as the boat runs in

connection with it, I should think we have shaken him off very effectively.”

“My dear Watson, you evidently did not realize my meaning

when I said that this man may be taken as being quite on the same intellectual plane as

myself. [476] You do not

imagine that if I were the pursuer I should allow myself to be baffled by so slight an

obstacle. Why, then, should you think so meanly of him?” “My dear Watson, you evidently did not realize my meaning

when I said that this man may be taken as being quite on the same intellectual plane as

myself. [476] You do not

imagine that if I were the pursuer I should allow myself to be baffled by so slight an

obstacle. Why, then, should you think so meanly of him?”

“What will he do?” “What will he do?”

“What I should do.” “What I should do.”

“What would you do, then?” “What would you do, then?”

“Engage a special.” “Engage a special.”

“But it must be late.” “But it must be late.”

“By no means. This train stops at Canterbury; and there

is always at least a quarter of an hour’s delay at the boat. He will catch us

there.” “By no means. This train stops at Canterbury; and there

is always at least a quarter of an hour’s delay at the boat. He will catch us

there.”

“One would think that we were the criminals. Let us have

him arrested on his arrival.” “One would think that we were the criminals. Let us have

him arrested on his arrival.”

“It would be to ruin the work of three months. We should

get the big fish, but the smaller would dart right and left out of the net. On Monday we

should have them all. No, an arrest is inadmissible.” “It would be to ruin the work of three months. We should

get the big fish, but the smaller would dart right and left out of the net. On Monday we

should have them all. No, an arrest is inadmissible.”

“What then?” “What then?”

“We shall get out at Canterbury.” “We shall get out at Canterbury.”

“And then?” “And then?”

“Well, then we must make a cross-country journey to

Newhaven, and so over to Dieppe. Moriarty will again do what I should do. He will get on

to Paris, mark down our luggage, and wait for two days at the depot. In the meantime we

shall treat ourselves to a couple of carpet-bags, encourage the manufactures of the

countries through which we travel, and make our way at our leisure into Switzerland, via

Luxembourg and Basle.” “Well, then we must make a cross-country journey to

Newhaven, and so over to Dieppe. Moriarty will again do what I should do. He will get on

to Paris, mark down our luggage, and wait for two days at the depot. In the meantime we

shall treat ourselves to a couple of carpet-bags, encourage the manufactures of the

countries through which we travel, and make our way at our leisure into Switzerland, via

Luxembourg and Basle.”

At Canterbury, therefore, we alighted, only to find that we

should have to wait an hour before we could get a train to Newhaven. At Canterbury, therefore, we alighted, only to find that we

should have to wait an hour before we could get a train to Newhaven.

I was still looking rather ruefully after the rapidly

disappearing luggage-van which contained my wardrobe, when Holmes pulled my sleeve and

pointed up the line. I was still looking rather ruefully after the rapidly

disappearing luggage-van which contained my wardrobe, when Holmes pulled my sleeve and

pointed up the line.

“Already, you see,” said he. “Already, you see,” said he.

Far away, from among the Kentish woods there rose a thin spray

of smoke. A minute later a carriage and engine could be seen flying along the open curve

which leads to the station. We had hardly time to take our place behind a pile of luggage

when it passed with a rattle and a roar, beating a blast of hot air into our faces. Far away, from among the Kentish woods there rose a thin spray

of smoke. A minute later a carriage and engine could be seen flying along the open curve

which leads to the station. We had hardly time to take our place behind a pile of luggage

when it passed with a rattle and a roar, beating a blast of hot air into our faces.

“There he goes,” said Holmes, as we watched the

carriage swing and rock over the points. “There are limits, you see, to our

friend’s intelligence. It would have been a coup-de-ma�tre had he deduced

what I would deduce and acted accordingly.” “There he goes,” said Holmes, as we watched the

carriage swing and rock over the points. “There are limits, you see, to our

friend’s intelligence. It would have been a coup-de-ma�tre had he deduced

what I would deduce and acted accordingly.”

“And what would he have done had he overtaken us?” “And what would he have done had he overtaken us?”

“There cannot be the least doubt that he would have made

a murderous attack upon me. It is, however, a game at which two may play. The question now

is whether we should take a premature lunch here, or run our chance of starving before we

reach the buffet at Newhaven.” “There cannot be the least doubt that he would have made

a murderous attack upon me. It is, however, a game at which two may play. The question now

is whether we should take a premature lunch here, or run our chance of starving before we

reach the buffet at Newhaven.”

We made our way to Brussels that night and spent two days

there, moving on upon the third day as far as Strasbourg. On the Monday morning Holmes had

telegraphed to the London police, and in the evening we found a reply waiting for us at

our hotel. Holmes tore it open, and then with a bitter curse hurled it into the grate. We made our way to Brussels that night and spent two days

there, moving on upon the third day as far as Strasbourg. On the Monday morning Holmes had

telegraphed to the London police, and in the evening we found a reply waiting for us at

our hotel. Holmes tore it open, and then with a bitter curse hurled it into the grate.

“I might have known it!” he groaned. “He has

escaped!” “I might have known it!” he groaned. “He has

escaped!”

“Moriarty?” “Moriarty?”

“They have secured the whole gang with the exception of

him. He has given [477] them

the slip. Of course, when I had left the country there was no one to cope with him. But I

did think that I had put the game in their hands. I think that you had better return to

England, Watson.” “They have secured the whole gang with the exception of

him. He has given [477] them

the slip. Of course, when I had left the country there was no one to cope with him. But I

did think that I had put the game in their hands. I think that you had better return to

England, Watson.”

“Why?” “Why?”

“Because you will find me a dangerous companion now. This

man’s occupation is gone. He is lost if he returns to London. If I read his character

right he will devote his whole energies to revenging himself upon me. He said as much in

our short interview, and I fancy that he meant it. I should certainly recommend you to

return to your practice.” “Because you will find me a dangerous companion now. This

man’s occupation is gone. He is lost if he returns to London. If I read his character

right he will devote his whole energies to revenging himself upon me. He said as much in

our short interview, and I fancy that he meant it. I should certainly recommend you to

return to your practice.”

It was hardly an appeal to be successful with one who was an

old campaigner as well as an old friend. We sat in the Strasbourg salle-�-manger arguing

the question for half an hour, but the same night we had resumed our journey and were well

on our way to Geneva. It was hardly an appeal to be successful with one who was an

old campaigner as well as an old friend. We sat in the Strasbourg salle-�-manger arguing

the question for half an hour, but the same night we had resumed our journey and were well

on our way to Geneva.

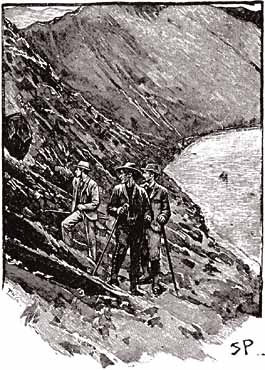

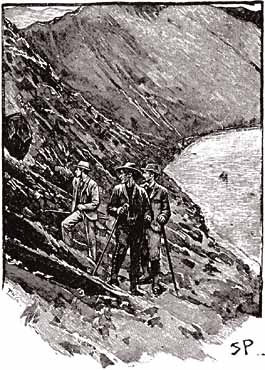

For a charming week we wandered up the valley of the Rhone,

and then, branching off at Leuk, we made our way over the Gemmi Pass, still deep in snow,

and so, by way of Interlaken, to Meiringen. It was a lovely trip, the dainty green of the

spring below, the virgin white of the winter above; but it was clear to me that never for

one instant did Holmes forget the shadow which lay across him. In the homely Alpine

villages or in the lonely mountain passes, I could still tell by his quick glancing eyes

and his sharp scrutiny of every face that passed us, that he was well convinced that, walk

where we would, we could not walk ourselves clear of the danger which was dogging our

footsteps. For a charming week we wandered up the valley of the Rhone,

and then, branching off at Leuk, we made our way over the Gemmi Pass, still deep in snow,

and so, by way of Interlaken, to Meiringen. It was a lovely trip, the dainty green of the

spring below, the virgin white of the winter above; but it was clear to me that never for

one instant did Holmes forget the shadow which lay across him. In the homely Alpine

villages or in the lonely mountain passes, I could still tell by his quick glancing eyes

and his sharp scrutiny of every face that passed us, that he was well convinced that, walk

where we would, we could not walk ourselves clear of the danger which was dogging our

footsteps.

Once, I remember, as we passed over the Gemmi, and walked

along the border of the melancholy Daubensee, a large rock which had been dislodged from

the ridge upon our right clattered down and roared into the lake behind us. In an instant

Holmes had raced up on to the ridge, and, standing upon a lofty pinnacle, craned his neck

in every direction. It was in vain that our guide assured him that a fall of stones was a

common chance in the springtime at that spot. He said nothing, but he smiled at me with

the air of a man who sees the fulfilment of that which he had expected. Once, I remember, as we passed over the Gemmi, and walked

along the border of the melancholy Daubensee, a large rock which had been dislodged from

the ridge upon our right clattered down and roared into the lake behind us. In an instant

Holmes had raced up on to the ridge, and, standing upon a lofty pinnacle, craned his neck

in every direction. It was in vain that our guide assured him that a fall of stones was a

common chance in the springtime at that spot. He said nothing, but he smiled at me with

the air of a man who sees the fulfilment of that which he had expected.

And yet for all his watchfulness he was never depressed. On

the contrary, I can never recollect having seen him in such exuberant spirits. Again and

again he recurred to the fact that if he could be assured that society was freed from

Professor Moriarty he would cheerfully bring his own career to a conclusion. And yet for all his watchfulness he was never depressed. On

the contrary, I can never recollect having seen him in such exuberant spirits. Again and

again he recurred to the fact that if he could be assured that society was freed from

Professor Moriarty he would cheerfully bring his own career to a conclusion.

“I think that I may go so far as to say, Watson, that I

have not lived wholly in vain,” he remarked. “If my record were closed to-night

I could still survey it with equanimity. The air of London is the sweeter for my presence.

In over a thousand cases I am not aware that I have ever used my powers upon the wrong

side. Of late I have been tempted to look into the problems furnished by nature rather

than those more superficial ones for which our artificial state of society is responsible.

Your memoirs will draw to an end, Watson, upon the day that I crown my career by the

capture or extinction of the most dangerous and capable criminal in Europe.” “I think that I may go so far as to say, Watson, that I

have not lived wholly in vain,” he remarked. “If my record were closed to-night

I could still survey it with equanimity. The air of London is the sweeter for my presence.

In over a thousand cases I am not aware that I have ever used my powers upon the wrong

side. Of late I have been tempted to look into the problems furnished by nature rather

than those more superficial ones for which our artificial state of society is responsible.

Your memoirs will draw to an end, Watson, upon the day that I crown my career by the

capture or extinction of the most dangerous and capable criminal in Europe.”

I shall be brief, and yet exact, in the little which remains

for me to tell. It is not a subject on which I would willingly dwell, and yet I am

conscious that a duty devolves upon me to omit no detail. I shall be brief, and yet exact, in the little which remains

for me to tell. It is not a subject on which I would willingly dwell, and yet I am

conscious that a duty devolves upon me to omit no detail.

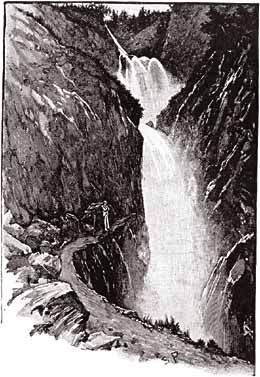

It was on the third of May that we reached the little village

of Meiringen, where we put up at the Englischer Hof, then kept by Peter Steiler the elder.

Our landlord was an intelligent man and spoke excellent English, having served for three [478] years as waiter at the

Grosvenor Hotel in London. At his advice, on the afternoon of the fourth we set off

together, with the intention of crossing the hills and spending the night at the hamlet of

Rosenlaui. We had strict injunctions, however, on no account to pass the falls of

Reichenbach, which are about halfway up the hills, without making a small detour to see

them. It was on the third of May that we reached the little village

of Meiringen, where we put up at the Englischer Hof, then kept by Peter Steiler the elder.

Our landlord was an intelligent man and spoke excellent English, having served for three [478] years as waiter at the

Grosvenor Hotel in London. At his advice, on the afternoon of the fourth we set off

together, with the intention of crossing the hills and spending the night at the hamlet of

Rosenlaui. We had strict injunctions, however, on no account to pass the falls of

Reichenbach, which are about halfway up the hills, without making a small detour to see

them.

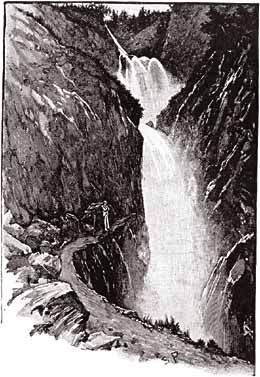

It is, indeed, a fearful place. The torrent, swollen by the

melting snow, plunges into a tremendous abyss, from which the spray rolls up like the

smoke from a burning house. The shaft into which the river hurls itself is an immense

chasm, lined by glistening coal-black rock, and narrowing into a creaming, boiling pit of

incalculable depth, which brims over and shoots the stream onward over its jagged lip. The

long sweep of green water roaring forever down, and the thick flickering curtain of spray

hissing forever upward, turn a man giddy with their constant whirl and clamour. We stood

near the edge peering down at the gleam of the breaking water far below us against the

black rocks, and listening to the half-human shout which came booming up with the spray

out of the abyss. It is, indeed, a fearful place. The torrent, swollen by the

melting snow, plunges into a tremendous abyss, from which the spray rolls up like the

smoke from a burning house. The shaft into which the river hurls itself is an immense

chasm, lined by glistening coal-black rock, and narrowing into a creaming, boiling pit of

incalculable depth, which brims over and shoots the stream onward over its jagged lip. The

long sweep of green water roaring forever down, and the thick flickering curtain of spray

hissing forever upward, turn a man giddy with their constant whirl and clamour. We stood

near the edge peering down at the gleam of the breaking water far below us against the

black rocks, and listening to the half-human shout which came booming up with the spray

out of the abyss.

The path has been cut halfway round the fall to afford a

complete view, but it ends abruptly, and the traveller has to return as he came. We had

turned to do so, when we saw a Swiss lad come running along it with a letter in his hand.

It bore the mark of the hotel which we had just left and was addressed to me by the

landlord. It appeared that within a very few minutes of our leaving, an English lady had

arrived who was in the last stage of consumption. She had wintered at Davos Platz and was

journeying now to join her friends at Lucerne, when a sudden hemorrhage had overtaken her.

It was thought that she could hardly live a few hours, but it would be a great consolation

to her to see an English doctor, and, if I would only return, etc. The good Steiler

assured me in a postscript that he would himself look upon my compliance as a very great

favour, since the lady absolutely refused to see a Swiss physician, and he could not but

feel that he was incurring a great responsibility. The path has been cut halfway round the fall to afford a

complete view, but it ends abruptly, and the traveller has to return as he came. We had

turned to do so, when we saw a Swiss lad come running along it with a letter in his hand.

It bore the mark of the hotel which we had just left and was addressed to me by the

landlord. It appeared that within a very few minutes of our leaving, an English lady had

arrived who was in the last stage of consumption. She had wintered at Davos Platz and was

journeying now to join her friends at Lucerne, when a sudden hemorrhage had overtaken her.

It was thought that she could hardly live a few hours, but it would be a great consolation

to her to see an English doctor, and, if I would only return, etc. The good Steiler

assured me in a postscript that he would himself look upon my compliance as a very great

favour, since the lady absolutely refused to see a Swiss physician, and he could not but

feel that he was incurring a great responsibility.

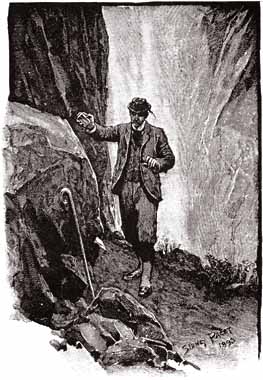

The appeal was one which could not be ignored. It was

impossible to refuse the request of a fellow-countrywoman dying in a strange land. Yet I

had my scruples about leaving Holmes. It was finally agreed, however, that he should

retain the young Swiss messenger with him as guide and companion while I returned to

Meiringen. My friend would stay some little time at the fall, he said, and would then walk

slowly over the hill to Rosenlaui, where I was to rejoin him in the evening. As I turned

away I saw Holmes, with his back against a rock and his arms folded, gazing down at the

rush of the waters. It was the last that I was ever destined to see of him in this world. The appeal was one which could not be ignored. It was

impossible to refuse the request of a fellow-countrywoman dying in a strange land. Yet I

had my scruples about leaving Holmes. It was finally agreed, however, that he should

retain the young Swiss messenger with him as guide and companion while I returned to

Meiringen. My friend would stay some little time at the fall, he said, and would then walk

slowly over the hill to Rosenlaui, where I was to rejoin him in the evening. As I turned

away I saw Holmes, with his back against a rock and his arms folded, gazing down at the

rush of the waters. It was the last that I was ever destined to see of him in this world.

When I was near the bottom of the descent I looked back. It

was impossible, from that position, to see the fall, but I could see the curving path

which winds over the shoulder of the hills and leads to it. Along this a man was, I

remember, walking very rapidly. When I was near the bottom of the descent I looked back. It

was impossible, from that position, to see the fall, but I could see the curving path

which winds over the shoulder of the hills and leads to it. Along this a man was, I

remember, walking very rapidly.

I could see his black figure clearly outlined against the

green behind him. I noted him, and the energy with which he walked, but he passed from my

mind again as I hurried on upon my errand. I could see his black figure clearly outlined against the

green behind him. I noted him, and the energy with which he walked, but he passed from my

mind again as I hurried on upon my errand.

It may have been a little over an hour before I reached

Meiringen. Old Steiler was standing at the porch of his hotel. It may have been a little over an hour before I reached

Meiringen. Old Steiler was standing at the porch of his hotel.

“Well,” said I, as I came hurrying up, “I trust

that she is no worse?” “Well,” said I, as I came hurrying up, “I trust

that she is no worse?”

A look of surprise passed over his face, and at the first

quiver of his eyebrows my heart turned to lead in my breast. A look of surprise passed over his face, and at the first

quiver of his eyebrows my heart turned to lead in my breast.

[479] “You

did not write this?” I said, pulling the letter from my pocket. “There is no

sick Englishwoman in the hotel?” [479] “You

did not write this?” I said, pulling the letter from my pocket. “There is no

sick Englishwoman in the hotel?”

“Certainly not!” he cried. “But it has the

hotel mark upon it! Ha, it must have been written by that tall Englishman who came in

after you had gone. He said– –” “Certainly not!” he cried. “But it has the

hotel mark upon it! Ha, it must have been written by that tall Englishman who came in

after you had gone. He said– –”

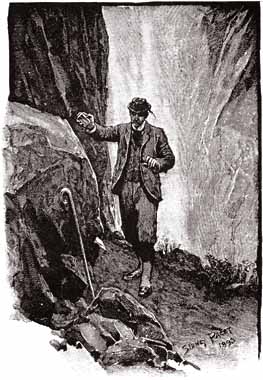

But I waited for none of the landlord’s explanation. In a

tingle of fear I was already running down the village street, and making for the path

which I had so lately descended. It had taken me an hour to come down. For all my efforts

two more had passed before I found myself at the fall of Reichenbach once more. There was

Holmes’s Alpine-stock still leaning against the rock by which I had left him. But

there was no sign of him, and it was in vain that I shouted. My only answer was my own

voice reverberating in a rolling echo from the cliffs around me. But I waited for none of the landlord’s explanation. In a

tingle of fear I was already running down the village street, and making for the path

which I had so lately descended. It had taken me an hour to come down. For all my efforts

two more had passed before I found myself at the fall of Reichenbach once more. There was

Holmes’s Alpine-stock still leaning against the rock by which I had left him. But

there was no sign of him, and it was in vain that I shouted. My only answer was my own

voice reverberating in a rolling echo from the cliffs around me.

It was the sight of that Alpine-stock which turned me cold and

sick. He had not gone to Rosenlaui, then. He had remained on that three-foot path, with

sheer wall on one side and sheer drop on the other, until his enemy had overtaken him. The

young Swiss had gone too. He had probably been in the pay of Moriarty and had left the two

men together. And then what had happened? Who was to tell us what had happened then? It was the sight of that Alpine-stock which turned me cold and

sick. He had not gone to Rosenlaui, then. He had remained on that three-foot path, with

sheer wall on one side and sheer drop on the other, until his enemy had overtaken him. The

young Swiss had gone too. He had probably been in the pay of Moriarty and had left the two

men together. And then what had happened? Who was to tell us what had happened then?

I stood for a minute or two to collect myself, for I was dazed

with the horror of the thing. Then I began to think of Holmes’s own methods and to

try to practise them in reading this tragedy. It was, alas, only too easy to do. During

our conversation we had not gone to the end of the path, and the Alpine-stock marked the

place where we had stood. The blackish soil is kept forever soft by the incessant drift of

spray, and a bird would leave its tread upon it. Two lines of footmarks were clearly

marked along the farther end of the path, both leading away from me. There were none

returning. A few yards from the end the soil was all ploughed up into a patch of mud, and

the brambles and ferns which fringed the chasm were torn and bedraggled. I lay upon my

face and peered over with the spray spouting up all around me. It had darkened since I

left, and now I could only see here and there the glistening of moisture upon the black

walls, and far away down at the end of the shaft the gleam of the broken water. I shouted;

but only that same half-human cry of the fall was borne back to my ears. I stood for a minute or two to collect myself, for I was dazed

with the horror of the thing. Then I began to think of Holmes’s own methods and to

try to practise them in reading this tragedy. It was, alas, only too easy to do. During

our conversation we had not gone to the end of the path, and the Alpine-stock marked the

place where we had stood. The blackish soil is kept forever soft by the incessant drift of

spray, and a bird would leave its tread upon it. Two lines of footmarks were clearly

marked along the farther end of the path, both leading away from me. There were none

returning. A few yards from the end the soil was all ploughed up into a patch of mud, and

the brambles and ferns which fringed the chasm were torn and bedraggled. I lay upon my

face and peered over with the spray spouting up all around me. It had darkened since I

left, and now I could only see here and there the glistening of moisture upon the black

walls, and far away down at the end of the shaft the gleam of the broken water. I shouted;

but only that same half-human cry of the fall was borne back to my ears.

But it was destined that I should, after all, have a last

word of greeting from my friend and comrade. I have said that his Alpine-stock had been

left leaning against a rock which jutted on to the path. From the top of this bowlder the

gleam of something bright caught my eye, and raising my hand I found that it came from the

silver cigarette-case which he used to carry. As I took it up a small square of paper upon

which it had lain fluttered down on to the ground. Unfolding it, I found that it consisted

of three pages torn from his notebook and addressed to me. It was characteristic of the

man that the direction was as precise, and the writing as firm and clear, as though it had

been written in his study. But it was destined that I should, after all, have a last

word of greeting from my friend and comrade. I have said that his Alpine-stock had been

left leaning against a rock which jutted on to the path. From the top of this bowlder the

gleam of something bright caught my eye, and raising my hand I found that it came from the

silver cigarette-case which he used to carry. As I took it up a small square of paper upon

which it had lain fluttered down on to the ground. Unfolding it, I found that it consisted

of three pages torn from his notebook and addressed to me. It was characteristic of the

man that the direction was as precise, and the writing as firm and clear, as though it had

been written in his study.

- MY DEAR WATSON [it said]:

I write these few lines through the courtesy of Mr. Moriarty,

who awaits my convenience for the final discussion of those questions which lie between

us. He has been giving me a sketch of the methods by which he avoided the English police

and kept himself informed of our movements. They certainly confirm the very high opinion

which I had formed of his abilities. I am pleased to think that I shall be able to free

society from any further effects of his presence, though I fear that it is at a cost which

will give pain to my [480] friends,

and especially, my dear Watson, to you. I have already explained to you, however, that my

career had in any case reached its crisis, and that no possible conclusion to it could be

more congenial to me than this. Indeed, if I may make a full confession to you, I was

quite convinced that the letter from Meiringen was a hoax, and I allowed you to depart on

that errand under the persuasion that some development of this sort would follow. Tell

Inspector Patterson that the papers which he needs to convict the gang are in pigeonhole

M., done up in a blue envelope and inscribed “Moriarty.” I made every

disposition of my property before leaving England and handed it to my brother Mycroft.

Pray give my greetings to Mrs. Watson, and believe me to be, my dear fellow, I write these few lines through the courtesy of Mr. Moriarty,

who awaits my convenience for the final discussion of those questions which lie between

us. He has been giving me a sketch of the methods by which he avoided the English police

and kept himself informed of our movements. They certainly confirm the very high opinion

which I had formed of his abilities. I am pleased to think that I shall be able to free

society from any further effects of his presence, though I fear that it is at a cost which

will give pain to my [480] friends,

and especially, my dear Watson, to you. I have already explained to you, however, that my

career had in any case reached its crisis, and that no possible conclusion to it could be

more congenial to me than this. Indeed, if I may make a full confession to you, I was

quite convinced that the letter from Meiringen was a hoax, and I allowed you to depart on

that errand under the persuasion that some development of this sort would follow. Tell

Inspector Patterson that the papers which he needs to convict the gang are in pigeonhole

M., done up in a blue envelope and inscribed “Moriarty.” I made every

disposition of my property before leaving England and handed it to my brother Mycroft.

Pray give my greetings to Mrs. Watson, and believe me to be, my dear fellow,

- Very sincerely yours,

- SHERLOCK HOLMES.

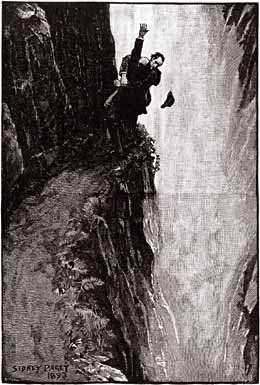

A few words may suffice to tell the little that remains. An examination by experts

leaves little doubt that a personal contest between the two men ended, as it could hardly

fail to end in such a situation, in their reeling over, locked in each other’s arms.

Any attempt at recovering the bodies was absolutely hopeless, and there, deep down in that

dreadful cauldron of swirling water and seething foam, will lie for all time the most

dangerous criminal and the foremost champion of the law of their generation. The Swiss

youth was never found again, and there can be no doubt that he was one of the numerous

agents whom Moriarty kept in his employ. As to the gang, it will be within the memory of

the public how completely the evidence which Holmes had accumulated exposed their

organization, and how heavily the hand of the dead man weighed upon them. Of their

terrible chief few details came out during the proceedings, and if I have now been

compelled to make a clear statement of his career, it is due to those injudicious

champions who have endeavoured to clear his memory by attacks upon him whom I shall ever

regard as the best and the wisest man whom I have ever known.

|

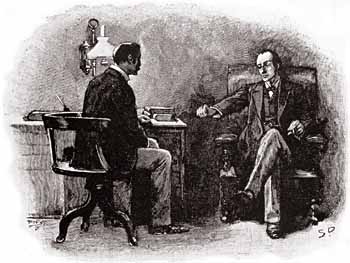

![]() It may be remembered that after my marriage, and my

subsequent start in private practice, the very intimate relations which had existed

between Holmes and myself became to some extent modified. He still came to me from time to

time when he desired a companion in his investigations, but these occasions grew more and

more seldom, until I find that in the year 1890 there were only three cases of which I

retain any record. During the winter of that year and the early spring of 1891, I saw in

the papers that he had been engaged by the French government upon a matter of supreme

importance, and I received two notes from Holmes, dated from Narbonne and from Nimes, from

which I gathered that his stay in France was likely to be a long one. It was with some

surprise, therefore, that I saw him walk into my consulting-room upon the evening of April

24th. It struck me that he was looking even paler and thinner than usual.

It may be remembered that after my marriage, and my

subsequent start in private practice, the very intimate relations which had existed

between Holmes and myself became to some extent modified. He still came to me from time to

time when he desired a companion in his investigations, but these occasions grew more and

more seldom, until I find that in the year 1890 there were only three cases of which I

retain any record. During the winter of that year and the early spring of 1891, I saw in

the papers that he had been engaged by the French government upon a matter of supreme

importance, and I received two notes from Holmes, dated from Narbonne and from Nimes, from

which I gathered that his stay in France was likely to be a long one. It was with some

surprise, therefore, that I saw him walk into my consulting-room upon the evening of April

24th. It struck me that he was looking even paler and thinner than usual.![]() “Yes, I have been using myself up rather too

freely,” he remarked, in answer to my look rather than to my words; “I have been

a little pressed of late. Have you any objection to my closing your shutters?”

“Yes, I have been using myself up rather too

freely,” he remarked, in answer to my look rather than to my words; “I have been

a little pressed of late. Have you any objection to my closing your shutters?”![]() The only light in the room came from the lamp upon the table

at which I had been reading. Holmes edged his way round the wall, and, flinging the

shutters together, he bolted them securely.

The only light in the room came from the lamp upon the table

at which I had been reading. Holmes edged his way round the wall, and, flinging the

shutters together, he bolted them securely.![]() “You are afraid of something?” I asked.

“You are afraid of something?” I asked.![]() [470] “Well,

I am.”

[470] “Well,

I am.”![]() “Of what?”

“Of what?”![]() “Of air-guns.”

“Of air-guns.”![]() “My dear Holmes, what do you mean?”

“My dear Holmes, what do you mean?”![]() “I think that you know me well enough, Watson, to

understand that I am by no means a nervous man. At the same time, it is stupidity rather

than courage to refuse to recognize danger when it is close upon you. Might I trouble you

for a match?” He drew in the smoke of his cigarette as if the soothing influence was

grateful to him.

“I think that you know me well enough, Watson, to

understand that I am by no means a nervous man. At the same time, it is stupidity rather

than courage to refuse to recognize danger when it is close upon you. Might I trouble you

for a match?” He drew in the smoke of his cigarette as if the soothing influence was

grateful to him.![]() “I must apologize for calling so late,” said he,

“and I must further beg you to be so unconventional as to allow me to leave your

house presently by scrambling over your back garden wall.”

“I must apologize for calling so late,” said he,

“and I must further beg you to be so unconventional as to allow me to leave your

house presently by scrambling over your back garden wall.”![]() “But what does it all mean?” I asked.

“But what does it all mean?” I asked.![]() He held out his hand, and I saw in the light of the lamp that

two of his knuckles were burst and bleeding.

He held out his hand, and I saw in the light of the lamp that

two of his knuckles were burst and bleeding.