|

|

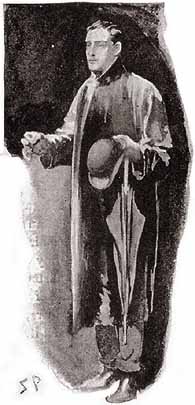

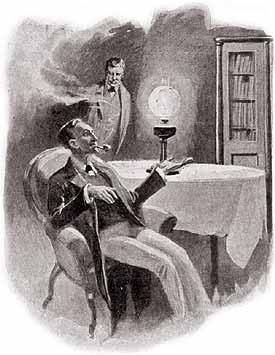

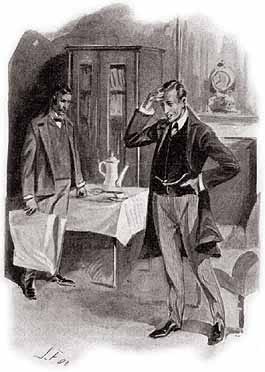

The man who entered was young, some two-and-twenty at the

outside, well-groomed and trimly clad, with something of refinement and delicacy in his

bearing. The streaming umbrella which he held in his hand, and his long shining waterproof

told of the fierce weather through which he had come. He looked about him anxiously in the

glare of the lamp, and I could see that his face was pale and his eyes heavy, like those

of a man who is weighed down with some great anxiety. The man who entered was young, some two-and-twenty at the

outside, well-groomed and trimly clad, with something of refinement and delicacy in his

bearing. The streaming umbrella which he held in his hand, and his long shining waterproof

told of the fierce weather through which he had come. He looked about him anxiously in the

glare of the lamp, and I could see that his face was pale and his eyes heavy, like those

of a man who is weighed down with some great anxiety.

“I owe you an apology,” he said, raising his golden

pince-nez to his eyes. “I trust that I am not intruding. I fear that I have brought

some traces of the storm and rain into your snug chamber.” “I owe you an apology,” he said, raising his golden

pince-nez to his eyes. “I trust that I am not intruding. I fear that I have brought

some traces of the storm and rain into your snug chamber.”

“Give me your coat and umbrella,” said Holmes.

“They may rest here on the hook and will be dry presently. You have come up from the

south-west, I see.” “Give me your coat and umbrella,” said Holmes.

“They may rest here on the hook and will be dry presently. You have come up from the

south-west, I see.”

“Yes, from Horsham.” “Yes, from Horsham.”

[219] “That

clay and chalk mixture which I see upon your toe caps is quite distinctive.” [219] “That

clay and chalk mixture which I see upon your toe caps is quite distinctive.”

“I have come for advice.” “I have come for advice.”

“That is easily got.” “That is easily got.”

“And help.” “And help.”

“That is not always so easy.” “That is not always so easy.”

“I have heard of you, Mr. Holmes. I heard from Major

Prendergast how you saved him in the Tankerville Club scandal.” “I have heard of you, Mr. Holmes. I heard from Major

Prendergast how you saved him in the Tankerville Club scandal.”

“Ah, of course. He was wrongfully accused of cheating at

cards.” “Ah, of course. He was wrongfully accused of cheating at

cards.”

“He said that you could solve anything.” “He said that you could solve anything.”

“He said too much.” “He said too much.”

“That you are never beaten.” “That you are never beaten.”

“I have been beaten four times–three times by men,

and once by a woman.” “I have been beaten four times–three times by men,

and once by a woman.”

“But what is that compared with the number of your

successes?” “But what is that compared with the number of your

successes?”

“It is true that I have been generally successful.” “It is true that I have been generally successful.”

“Then you may be so with me.” “Then you may be so with me.”

“I beg that you will draw your chair up to the fire and

favour me with some details as to your case.” “I beg that you will draw your chair up to the fire and

favour me with some details as to your case.”

“It is no ordinary one.” “It is no ordinary one.”

“None of those which come to me are. I am the last court

of appeal.” “None of those which come to me are. I am the last court

of appeal.”

“And yet I question, sir, whether, in all your

experience, you have ever listened to a more mysterious and inexplicable chain of events

than those which have happened in my own family.” “And yet I question, sir, whether, in all your

experience, you have ever listened to a more mysterious and inexplicable chain of events

than those which have happened in my own family.”

“You fill me with interest,” said Holmes. “Pray

give us the essential facts from the commencement, and I can afterwards question you as to

those details which seem to me to be most important.” “You fill me with interest,” said Holmes. “Pray

give us the essential facts from the commencement, and I can afterwards question you as to

those details which seem to me to be most important.”

The young man pulled his chair up and pushed his wet feet out

towards the blaze. The young man pulled his chair up and pushed his wet feet out

towards the blaze.

“My name,” said he, “is John Openshaw, but my

own affairs have, as far as I can understand, little to do with this awful business. It is

a hereditary matter; so in order to give you an idea of the facts, I must go back to the

commencement of the affair. “My name,” said he, “is John Openshaw, but my

own affairs have, as far as I can understand, little to do with this awful business. It is

a hereditary matter; so in order to give you an idea of the facts, I must go back to the

commencement of the affair.

“You must know that my grandfather had two sons–my

uncle Elias and my father Joseph. My father had a small factory at Coventry, which he

enlarged at the time of the invention of bicycling. He was a patentee of the Openshaw

unbreakable tire, and his business met with such success that he was able to sell it and

to retire upon a handsome competence. “You must know that my grandfather had two sons–my

uncle Elias and my father Joseph. My father had a small factory at Coventry, which he

enlarged at the time of the invention of bicycling. He was a patentee of the Openshaw

unbreakable tire, and his business met with such success that he was able to sell it and

to retire upon a handsome competence.

“My uncle Elias emigrated to America when he was a young

man and became a planter in Florida, where he was reported to have done very well. At the

time of the war he fought in Jackson’s army, and afterwards under Hood, where he rose

to be a colonel. When Lee laid down his arms my uncle returned to his plantation, where he

remained for three or four years. About 1869 or 1870 he came back to Europe and took a

small estate in Sussex, near Horsham. He had made a very considerable fortune in the

States, and his reason for leaving them was his aversion to the negroes, and his dislike

of the Republican policy in extending the franchise to them. He was a singular man, fierce

and quick-tempered, very foul-mouthed when he was angry, and of a most retiring

disposition. During all the years that he lived at Horsham, I doubt if ever he set foot in

the town. He had a garden and two or three fields round his house, and there he would take

his exercise, though very often for weeks on end he would never leave his room. He drank [220] a great deal of brandy and smoked

very heavily, but he would see no society and did not want any friends, not even his own

brother. “My uncle Elias emigrated to America when he was a young

man and became a planter in Florida, where he was reported to have done very well. At the

time of the war he fought in Jackson’s army, and afterwards under Hood, where he rose

to be a colonel. When Lee laid down his arms my uncle returned to his plantation, where he

remained for three or four years. About 1869 or 1870 he came back to Europe and took a

small estate in Sussex, near Horsham. He had made a very considerable fortune in the

States, and his reason for leaving them was his aversion to the negroes, and his dislike

of the Republican policy in extending the franchise to them. He was a singular man, fierce

and quick-tempered, very foul-mouthed when he was angry, and of a most retiring

disposition. During all the years that he lived at Horsham, I doubt if ever he set foot in

the town. He had a garden and two or three fields round his house, and there he would take

his exercise, though very often for weeks on end he would never leave his room. He drank [220] a great deal of brandy and smoked

very heavily, but he would see no society and did not want any friends, not even his own

brother.

“He didn’t mind me; in fact, he took a fancy to me,

for at the time when he saw me first I was a youngster of twelve or so. This would be in

the year 1878, after he had been eight or nine years in England. He begged my father to

let me live with him, and he was very kind to me in his way. When he was sober he used to

be fond of playing backgammon and draughts with me, and he would make me his

representative both with the servants and with the tradespeople, so that by the time that

I was sixteen I was quite master of the house. I kept all the keys and could go where I

liked and do what I liked, so long as I did not disturb him in his privacy. There was one

singular exception, however, for he had a single room, a lumber-room up among the attics,

which was invariably locked, and which he would never permit either me or anyone else to

enter. With a boy’s curiosity I have peeped through the keyhole, but I was never able

to see more than such a collection of old trunks and bundles as would be expected in such

a room. “He didn’t mind me; in fact, he took a fancy to me,

for at the time when he saw me first I was a youngster of twelve or so. This would be in

the year 1878, after he had been eight or nine years in England. He begged my father to

let me live with him, and he was very kind to me in his way. When he was sober he used to

be fond of playing backgammon and draughts with me, and he would make me his

representative both with the servants and with the tradespeople, so that by the time that

I was sixteen I was quite master of the house. I kept all the keys and could go where I

liked and do what I liked, so long as I did not disturb him in his privacy. There was one

singular exception, however, for he had a single room, a lumber-room up among the attics,

which was invariably locked, and which he would never permit either me or anyone else to

enter. With a boy’s curiosity I have peeped through the keyhole, but I was never able

to see more than such a collection of old trunks and bundles as would be expected in such

a room.

“One day–it was in March, 1883–a letter with a

foreign stamp lay upon the table in front of the colonel’s plate. It was not a common

thing for him to receive letters, for his bills were all paid in ready money, and he had

no friends of any sort. ‘From India!’ said he as he took it up,

‘Pondicherry postmark! What can this be?’ Opening it hurriedly, out there jumped

five little dried orange pips, which pattered down upon his plate. I began to laugh at

this, but the laugh was struck from my lips at the sight of his face. His lip had fallen,

his eyes were protruding, his skin the colour of putty, and he glared at the envelope

which he still held in his trembling hand, ‘K. K. K.!’ he shrieked, and then,

‘My God, my God, my sins have overtaken me!’ “One day–it was in March, 1883–a letter with a

foreign stamp lay upon the table in front of the colonel’s plate. It was not a common

thing for him to receive letters, for his bills were all paid in ready money, and he had

no friends of any sort. ‘From India!’ said he as he took it up,

‘Pondicherry postmark! What can this be?’ Opening it hurriedly, out there jumped

five little dried orange pips, which pattered down upon his plate. I began to laugh at

this, but the laugh was struck from my lips at the sight of his face. His lip had fallen,

his eyes were protruding, his skin the colour of putty, and he glared at the envelope

which he still held in his trembling hand, ‘K. K. K.!’ he shrieked, and then,

‘My God, my God, my sins have overtaken me!’

“‘What is it, uncle?’ I cried. “‘What is it, uncle?’ I cried.

“‘Death,’ said he, and rising from the table he

retired to his room, leaving me palpitating with horror. I took up the envelope and saw

scrawled in red ink upon the inner flap, just above the gum, the letter K three times

repeated. There was nothing else save the five dried pips. What could be the reason of his

overpowering terror? I left the breakfast-table, and as I ascended the stair I met him

coming down with an old rusty key, which must have belonged to the attic, in one hand, and

a small brass box, like a cashbox, in the other. “‘Death,’ said he, and rising from the table he

retired to his room, leaving me palpitating with horror. I took up the envelope and saw

scrawled in red ink upon the inner flap, just above the gum, the letter K three times

repeated. There was nothing else save the five dried pips. What could be the reason of his

overpowering terror? I left the breakfast-table, and as I ascended the stair I met him

coming down with an old rusty key, which must have belonged to the attic, in one hand, and

a small brass box, like a cashbox, in the other.

“‘They may do what they like, but I’ll

checkmate them still,’ said he with an oath. ‘Tell Mary that I shall want a fire

in my room to-day, and send down to Fordham, the Horsham lawyer.’ “‘They may do what they like, but I’ll

checkmate them still,’ said he with an oath. ‘Tell Mary that I shall want a fire

in my room to-day, and send down to Fordham, the Horsham lawyer.’

“I did as he ordered, and when the lawyer arrived I was

asked to step up to the room. The fire was burning brightly, and in the grate there was a

mass of black, fluffy ashes, as of burned paper, while the brass box stood open and empty

beside it. As I glanced at the box I noticed, with a start, that upon the lid was printed

the treble K which I had read in the morning upon the envelope. “I did as he ordered, and when the lawyer arrived I was

asked to step up to the room. The fire was burning brightly, and in the grate there was a

mass of black, fluffy ashes, as of burned paper, while the brass box stood open and empty

beside it. As I glanced at the box I noticed, with a start, that upon the lid was printed

the treble K which I had read in the morning upon the envelope.

“‘I wish you, John,’ said my uncle, ‘to

witness my will. I leave my estate, with all its advantages and all its disadvantages, to

my brother, your father, whence it will, no doubt, descend to you. If you can enjoy it in

peace, well and good! If you find you cannot, take my advice, my boy, and leave it to your

deadliest enemy. I am sorry to give you such a two-edged thing, but I can’t say what

turn things are going to take. Kindly sign the paper where Mr. Fordham shows you.’ “‘I wish you, John,’ said my uncle, ‘to

witness my will. I leave my estate, with all its advantages and all its disadvantages, to

my brother, your father, whence it will, no doubt, descend to you. If you can enjoy it in

peace, well and good! If you find you cannot, take my advice, my boy, and leave it to your

deadliest enemy. I am sorry to give you such a two-edged thing, but I can’t say what

turn things are going to take. Kindly sign the paper where Mr. Fordham shows you.’

“I signed the paper as directed, and the lawyer took it

away with him. The singular incident made, as you may think, the deepest impression upon

me, and [221] I pondered

over it and turned it every way in my mind without being able to make anything of it. Yet

I could not shake off the vague feeling of dread which it left behind, though the

sensation grew less keen as the weeks passed, and nothing happened to disturb the usual

routine of our lives. I could see a change in my uncle, however. He drank more than ever,

and he was less inclined for any sort of society. Most of his time he would spend in his

room, with the door locked upon the inside, but sometimes he would emerge in a sort of

drunken frenzy and would burst out of the house and tear about the garden with a revolver

in his hand, screaming out that he was afraid of no man, and that he was not to be cooped

up, like a sheep in a pen, by man or devil. When these hot fits were over, however, he

would rush tumultuously in at the door and lock and bar it behind him, like a man who can

brazen it out no longer against the terror which lies at the roots of his soul. At such

times I have seen his face, even on a cold day, glisten with moisture, as though it were

new raised from a basin. “I signed the paper as directed, and the lawyer took it

away with him. The singular incident made, as you may think, the deepest impression upon

me, and [221] I pondered

over it and turned it every way in my mind without being able to make anything of it. Yet

I could not shake off the vague feeling of dread which it left behind, though the

sensation grew less keen as the weeks passed, and nothing happened to disturb the usual

routine of our lives. I could see a change in my uncle, however. He drank more than ever,

and he was less inclined for any sort of society. Most of his time he would spend in his

room, with the door locked upon the inside, but sometimes he would emerge in a sort of

drunken frenzy and would burst out of the house and tear about the garden with a revolver

in his hand, screaming out that he was afraid of no man, and that he was not to be cooped

up, like a sheep in a pen, by man or devil. When these hot fits were over, however, he

would rush tumultuously in at the door and lock and bar it behind him, like a man who can

brazen it out no longer against the terror which lies at the roots of his soul. At such

times I have seen his face, even on a cold day, glisten with moisture, as though it were

new raised from a basin.

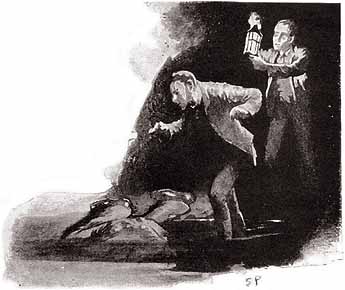

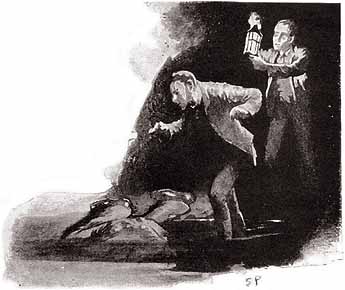

“Well, to come to an end of the matter, Mr. Holmes,

and not to abuse your patience, there came a night when he made one of those drunken

sallies from which he never came back. We found him, when we went to search for him, face

downward in a little green-scummed pool, which lay at the foot of the garden. There was no

sign of any violence, and the water was but two feet deep, so that the jury, having regard

to his known eccentricity, brought in a verdict of ‘suicide.’ But I, who knew

how he winced from the very thought of death, had much ado to persuade myself that he had

gone out of his way to meet it. The matter passed, however, and my father entered into

possession of the estate, and of some �14,000, which lay to his credit at the bank.” “Well, to come to an end of the matter, Mr. Holmes,

and not to abuse your patience, there came a night when he made one of those drunken

sallies from which he never came back. We found him, when we went to search for him, face

downward in a little green-scummed pool, which lay at the foot of the garden. There was no

sign of any violence, and the water was but two feet deep, so that the jury, having regard

to his known eccentricity, brought in a verdict of ‘suicide.’ But I, who knew

how he winced from the very thought of death, had much ado to persuade myself that he had

gone out of his way to meet it. The matter passed, however, and my father entered into

possession of the estate, and of some �14,000, which lay to his credit at the bank.”

“One moment,” Holmes interposed, “your

statement is, I foresee, one of the most remarkable to which I have ever listened. Let me

have the date of the reception by your uncle of the letter, and the date of his supposed

suicide.” “One moment,” Holmes interposed, “your

statement is, I foresee, one of the most remarkable to which I have ever listened. Let me

have the date of the reception by your uncle of the letter, and the date of his supposed

suicide.”

“The letter arrived on March 10, 1883. His death was

seven weeks later, upon the night of May 2d.” “The letter arrived on March 10, 1883. His death was

seven weeks later, upon the night of May 2d.”

“Thank you. Pray proceed.” “Thank you. Pray proceed.”

“When my father took over the Horsham property, he, at my

request, made a careful examination of the attic, which had been always locked up. We

found the brass box there, although its contents had been destroyed. On the inside of the

cover was a paper label, with the initials of K. K. K. repeated upon it, and

‘Letters, memoranda, receipts, and a register’ written beneath. These, we

presume, indicated the nature of the papers which had been destroyed by Colonel Openshaw.

For the rest, there was nothing of much importance in the attic save a great many

scattered papers and note-books bearing upon my uncle’s life in America. Some of them

were of the war time and showed that he had done his duty well and had borne the repute of

a brave soldier. Others were of a date during the reconstruction of the Southern states,

and were mostly concerned with politics, for he had evidently taken a strong part in

opposing the carpet-bag politicians who had been sent down from the North. “When my father took over the Horsham property, he, at my

request, made a careful examination of the attic, which had been always locked up. We

found the brass box there, although its contents had been destroyed. On the inside of the

cover was a paper label, with the initials of K. K. K. repeated upon it, and

‘Letters, memoranda, receipts, and a register’ written beneath. These, we

presume, indicated the nature of the papers which had been destroyed by Colonel Openshaw.

For the rest, there was nothing of much importance in the attic save a great many

scattered papers and note-books bearing upon my uncle’s life in America. Some of them

were of the war time and showed that he had done his duty well and had borne the repute of

a brave soldier. Others were of a date during the reconstruction of the Southern states,

and were mostly concerned with politics, for he had evidently taken a strong part in

opposing the carpet-bag politicians who had been sent down from the North.

“Well, it was the beginning of ’84 when my father

came to live at Horsham, and all went as well as possible with us until the January of

’85. On the fourth day after the new year I heard my father give a sharp cry of

surprise as we sat together at the breakfast-table. There he was, sitting with a newly

opened envelope in one hand and five dried orange pips in the outstretched palm of the

other one. He had always laughed at what he called my cock-and-bull story about the

colonel, but [222] he looked

very scared and puzzled now that the same thing had come upon himself. “Well, it was the beginning of ’84 when my father

came to live at Horsham, and all went as well as possible with us until the January of

’85. On the fourth day after the new year I heard my father give a sharp cry of

surprise as we sat together at the breakfast-table. There he was, sitting with a newly

opened envelope in one hand and five dried orange pips in the outstretched palm of the

other one. He had always laughed at what he called my cock-and-bull story about the

colonel, but [222] he looked

very scared and puzzled now that the same thing had come upon himself.

“‘Why, what on earth does this mean, John?’

he stammered. “‘Why, what on earth does this mean, John?’

he stammered.

“My heart had turned to lead. ‘It is K. K. K.,’

said I. “My heart had turned to lead. ‘It is K. K. K.,’

said I.

“He looked inside the envelope. ‘So it is,’ he

cried. ‘Here are the very letters. But what is this written above them?’ “He looked inside the envelope. ‘So it is,’ he

cried. ‘Here are the very letters. But what is this written above them?’

“‘Put the papers on the sundial,’ I read,

peeping over his shoulder. “‘Put the papers on the sundial,’ I read,

peeping over his shoulder.

“‘What papers? What sundial?’ he asked. “‘What papers? What sundial?’ he asked.

“‘The sundial in the garden. There is no

other,’ said I; ‘but the papers must be those that are destroyed.’ “‘The sundial in the garden. There is no

other,’ said I; ‘but the papers must be those that are destroyed.’

“‘Pooh!’ said he, gripping hard at his courage.

‘We are in a civilized land here, and we can’t have tomfoolery of this kind.

Where does the thing come from?’ “‘Pooh!’ said he, gripping hard at his courage.

‘We are in a civilized land here, and we can’t have tomfoolery of this kind.

Where does the thing come from?’

“‘From Dundee,’ I answered, glancing at the

postmark. “‘From Dundee,’ I answered, glancing at the

postmark.

“‘Some preposterous practical joke,’ said he.

‘What have I to do with sundials and papers? I shall take no notice of such

nonsense.’ “‘Some preposterous practical joke,’ said he.

‘What have I to do with sundials and papers? I shall take no notice of such

nonsense.’

“‘I should certainly speak to the police,’ I

said. “‘I should certainly speak to the police,’ I

said.

“‘And be laughed at for my pains. Nothing of the

sort.’ “‘And be laughed at for my pains. Nothing of the

sort.’

“‘Then let me do so?’ “‘Then let me do so?’

“‘No, I forbid you. I won’t have a fuss made

about such nonsense.’ “‘No, I forbid you. I won’t have a fuss made

about such nonsense.’

“It was in vain to argue with him, for he was a very

obstinate man. I went about, however, with a heart which was full of forebodings. “It was in vain to argue with him, for he was a very

obstinate man. I went about, however, with a heart which was full of forebodings.

“On the third day after the coming of the letter my

father went from home to visit an old friend of his, Major Freebody, who is in command of

one of the forts upon Portsdown Hill. I was glad that he should go, for it seemed to me

that he was farther from danger when he was away from home. In that, however, I was in

error. Upon the second day of his absence I received a telegram from the major, imploring

me to come at once. My father had fallen over one of the deep chalk-pits which abound in

the neighbourhood, and was lying senseless, with a shattered skull. I hurried to him, but

he passed away without having ever recovered his consciousness. He had, as it appears,

been returning from Fareham in the twilight, and as the country was unknown to him, and

the chalk-pit unfenced, the jury had no hesitation in bringing in a verdict of ‘death

from accidental causes.’ Carefully as I examined every fact connected with his death,

I was unable to find anything which could suggest the idea of murder. There were no signs

of violence, no footmarks, no robbery, no record of strangers having been seen upon the

roads. And yet I need not tell you that my mind was far from at ease, and that I was

well-nigh certain that some foul plot had been woven round him. “On the third day after the coming of the letter my

father went from home to visit an old friend of his, Major Freebody, who is in command of

one of the forts upon Portsdown Hill. I was glad that he should go, for it seemed to me

that he was farther from danger when he was away from home. In that, however, I was in

error. Upon the second day of his absence I received a telegram from the major, imploring

me to come at once. My father had fallen over one of the deep chalk-pits which abound in

the neighbourhood, and was lying senseless, with a shattered skull. I hurried to him, but

he passed away without having ever recovered his consciousness. He had, as it appears,

been returning from Fareham in the twilight, and as the country was unknown to him, and

the chalk-pit unfenced, the jury had no hesitation in bringing in a verdict of ‘death

from accidental causes.’ Carefully as I examined every fact connected with his death,

I was unable to find anything which could suggest the idea of murder. There were no signs

of violence, no footmarks, no robbery, no record of strangers having been seen upon the

roads. And yet I need not tell you that my mind was far from at ease, and that I was

well-nigh certain that some foul plot had been woven round him.

“In this sinister way I came into my inheritance. You

will ask me why I did not dispose of it? I answer, because I was well convinced that our

troubles were in some way dependent upon an incident in my uncle’s life, and that the

danger would be as pressing in one house as in another. “In this sinister way I came into my inheritance. You

will ask me why I did not dispose of it? I answer, because I was well convinced that our

troubles were in some way dependent upon an incident in my uncle’s life, and that the

danger would be as pressing in one house as in another.

“It was in January, ’85, that my poor father met his

end, and two years and eight months have elapsed since then. During that time I have lived

happily at Horsham, and I had begun to hope that this curse had passed away from the

family, and that it had ended with the last generation. I had begun to take comfort too

soon, however; yesterday morning the blow fell in the very shape in which it had come upon

my father.” “It was in January, ’85, that my poor father met his

end, and two years and eight months have elapsed since then. During that time I have lived

happily at Horsham, and I had begun to hope that this curse had passed away from the

family, and that it had ended with the last generation. I had begun to take comfort too

soon, however; yesterday morning the blow fell in the very shape in which it had come upon

my father.”

The young man took from his waistcoat a crumpled envelope,

and turning to the table he shook out upon it five little dried orange pips. The young man took from his waistcoat a crumpled envelope,

and turning to the table he shook out upon it five little dried orange pips.

“This is the envelope,” he continued. “The

postmark is London–eastern [223] division.

Within are the very words which were upon my father’s last message: ‘K. K.

K.’; and then ‘Put the papers on the sundial.’” “This is the envelope,” he continued. “The

postmark is London–eastern [223] division.

Within are the very words which were upon my father’s last message: ‘K. K.

K.’; and then ‘Put the papers on the sundial.’”

“What have you done?” asked Holmes. “What have you done?” asked Holmes.

“Nothing.” “Nothing.”

“Nothing?” “Nothing?”

“To tell the truth”–he sank his face into his

thin, white hands–“I have felt helpless. I have felt like one of those poor

rabbits when the snake is writhing towards it. I seem to be in the grasp of some

resistless, inexorable evil, which no foresight and no precautions can guard

against.” “To tell the truth”–he sank his face into his

thin, white hands–“I have felt helpless. I have felt like one of those poor

rabbits when the snake is writhing towards it. I seem to be in the grasp of some

resistless, inexorable evil, which no foresight and no precautions can guard

against.”

“Tut! tut!” cried Sherlock Holmes. “You must

act, man, or you are lost. Nothing but energy can save you. This is no time for

despair.” “Tut! tut!” cried Sherlock Holmes. “You must

act, man, or you are lost. Nothing but energy can save you. This is no time for

despair.”

“I have seen the police.” “I have seen the police.”

“Ah!” “Ah!”

“But they listened to my story with a smile. I am

convinced that the inspector has formed the opinion that the letters are all practical

jokes, and that the deaths of my relations were really accidents, as the jury stated, and

were not to be connected with the warnings.” “But they listened to my story with a smile. I am

convinced that the inspector has formed the opinion that the letters are all practical

jokes, and that the deaths of my relations were really accidents, as the jury stated, and

were not to be connected with the warnings.”

Holmes shook his clenched hands in the air. “Incredible

imbecility!” he cried. Holmes shook his clenched hands in the air. “Incredible

imbecility!” he cried.

“They have, however, allowed me a policeman, who may

remain in the house with me.” “They have, however, allowed me a policeman, who may

remain in the house with me.”

“Has he come with you to-night?” “Has he come with you to-night?”

“No. His orders were to stay in the house.” “No. His orders were to stay in the house.”

Again Holmes raved in the air. Again Holmes raved in the air.

“Why did you come to me,” he cried, “and, above

all, why did you not come at once?” “Why did you come to me,” he cried, “and, above

all, why did you not come at once?”

“I did not know. It was only to-day that I spoke to Major

Prendergast about my troubles and was advised by him to come to you.” “I did not know. It was only to-day that I spoke to Major

Prendergast about my troubles and was advised by him to come to you.”

“It is really two days since you had the letter. We

should have acted before this. You have no further evidence, I suppose, than that which

you have placed before us–no suggestive detail which might help us?” “It is really two days since you had the letter. We

should have acted before this. You have no further evidence, I suppose, than that which

you have placed before us–no suggestive detail which might help us?”

“There is one thing,” said John Openshaw. He

rummaged in his coat pocket, and, drawing out a piece of discoloured, blue-tinted paper,

he laid it out upon the table. “I have some remembrance,” said he, “that on

the day when my uncle burned the papers I observed that the small, unburned margins which

lay amid the ashes were of this particular colour. I found this single sheet upon the

floor of his room, and I am inclined to think that it may be one of the papers which has,

perhaps, fluttered out from among the others, and in that way has escaped destruction.

Beyond the mention of pips, I do not see that it helps us much. I think myself that it is

a page from some private diary. The writing is undoubtedly my uncle’s.” “There is one thing,” said John Openshaw. He

rummaged in his coat pocket, and, drawing out a piece of discoloured, blue-tinted paper,

he laid it out upon the table. “I have some remembrance,” said he, “that on

the day when my uncle burned the papers I observed that the small, unburned margins which

lay amid the ashes were of this particular colour. I found this single sheet upon the

floor of his room, and I am inclined to think that it may be one of the papers which has,

perhaps, fluttered out from among the others, and in that way has escaped destruction.

Beyond the mention of pips, I do not see that it helps us much. I think myself that it is

a page from some private diary. The writing is undoubtedly my uncle’s.”

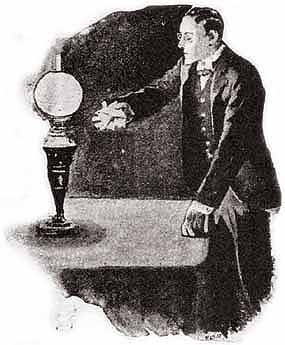

Holmes moved the lamp, and we both bent over the sheet of

paper, which showed by its ragged edge that it had indeed been torn from a book. It was

headed, “March, 1869,” and beneath were the following enigmatical notices: Holmes moved the lamp, and we both bent over the sheet of

paper, which showed by its ragged edge that it had indeed been torn from a book. It was

headed, “March, 1869,” and beneath were the following enigmatical notices:

| 4th. |

Hudson came. Same old platform. |

| 7th. |

Set the pips on McCauley, Paramore, and John Swain, of St.

Augustine. |

| 9th. |

McCauley cleared. |

| 10th. |

John Swain cleared. |

| 12th. |

Visited Paramore. All well. |

[224] “Thank

you!” said Holmes, folding up the paper and returning it to our visitor. “And

now you must on no account lose another instant. We cannot spare time even to discuss what

you have told me. You must get home instantly and act.” [224] “Thank

you!” said Holmes, folding up the paper and returning it to our visitor. “And

now you must on no account lose another instant. We cannot spare time even to discuss what

you have told me. You must get home instantly and act.”

“What shall I do?” “What shall I do?”

“There is but one thing to do. It must be done at once.

You must put this piece of paper which you have shown us into the brass box which you have

described. You must also put in a note to say that all the other papers were burned by

your uncle, and that this is the only one which remains. You must assert that in such

words as will carry conviction with them. Having done this, you must at once put the box

out upon the sundial, as directed. Do you understand?” “There is but one thing to do. It must be done at once.

You must put this piece of paper which you have shown us into the brass box which you have

described. You must also put in a note to say that all the other papers were burned by

your uncle, and that this is the only one which remains. You must assert that in such

words as will carry conviction with them. Having done this, you must at once put the box

out upon the sundial, as directed. Do you understand?”

“Entirely.” “Entirely.”

“Do not think of revenge, or anything of the sort, at

present. I think that we may gain that by means of the law; but we have our web to weave,

while theirs is already woven. The first consideration is to remove the pressing danger

which threatens you. The second is to clear up the mystery and to punish the guilty

parties.” “Do not think of revenge, or anything of the sort, at

present. I think that we may gain that by means of the law; but we have our web to weave,

while theirs is already woven. The first consideration is to remove the pressing danger

which threatens you. The second is to clear up the mystery and to punish the guilty

parties.”

“I thank you,” said the young man, rising and

pulling on his overcoat. “You have given me fresh life and hope. I shall certainly do

as you advise.” “I thank you,” said the young man, rising and

pulling on his overcoat. “You have given me fresh life and hope. I shall certainly do

as you advise.”

“Do not lose an instant. And, above all, take care of

yourself in the meanwhile, for I do not think that there can be a doubt that you are

threatened by a very real and imminent danger. How do you go back?” “Do not lose an instant. And, above all, take care of

yourself in the meanwhile, for I do not think that there can be a doubt that you are

threatened by a very real and imminent danger. How do you go back?”

“By train from Waterloo.” “By train from Waterloo.”

“It is not yet nine. The streets will be crowded, so I

trust that you may be in safety. And yet you cannot guard yourself too closely.” “It is not yet nine. The streets will be crowded, so I

trust that you may be in safety. And yet you cannot guard yourself too closely.”

“I am armed.” “I am armed.”

“That is well. To-morrow I shall set to work upon your

case.” “That is well. To-morrow I shall set to work upon your

case.”

“I shall see you at Horsham, then?” “I shall see you at Horsham, then?”

“No, your secret lies in London. It is there that I shall

seek it.” “No, your secret lies in London. It is there that I shall

seek it.”

“Then I shall call upon you in a day, or in two days,

with news as to the box and the papers. I shall take your advice in every

particular.” He shook hands with us and took his leave. Outside the wind still

screamed and the rain splashed and pattered against the windows. This strange, wild story

seemed to have come to us from amid the mad elements–blown in upon us like a sheet of

sea-weed in a gale–and now to have been reabsorbed by them once more. “Then I shall call upon you in a day, or in two days,

with news as to the box and the papers. I shall take your advice in every

particular.” He shook hands with us and took his leave. Outside the wind still

screamed and the rain splashed and pattered against the windows. This strange, wild story

seemed to have come to us from amid the mad elements–blown in upon us like a sheet of

sea-weed in a gale–and now to have been reabsorbed by them once more.

Sherlock Holmes sat for some time in silence, with his head

sunk forward and his eyes bent upon the red glow of the fire. Then he lit his pipe, and

leaning back in his chair he watched the blue smoke-rings as they chased each other up to

the ceiling. Sherlock Holmes sat for some time in silence, with his head

sunk forward and his eyes bent upon the red glow of the fire. Then he lit his pipe, and

leaning back in his chair he watched the blue smoke-rings as they chased each other up to

the ceiling.

“I think, Watson,” he remarked at last, “that

of all our cases we have had none more fantastic than this.” “I think, Watson,” he remarked at last, “that

of all our cases we have had none more fantastic than this.”

“Save, perhaps, the Sign of Four.” “Save, perhaps, the Sign of Four.”

“Well, yes. Save, perhaps, that. And yet this John

Openshaw seems to me to be walking amid even greater perils than did the Sholtos.” “Well, yes. Save, perhaps, that. And yet this John

Openshaw seems to me to be walking amid even greater perils than did the Sholtos.”

“But have you,” I asked, “formed any definite

conception as to what these perils are?” “But have you,” I asked, “formed any definite

conception as to what these perils are?”

“There can be no question as to their nature,” he

answered. “There can be no question as to their nature,” he

answered.

“Then what are they? Who is this K. K. K., and why does

he pursue this unhappy family?” “Then what are they? Who is this K. K. K., and why does

he pursue this unhappy family?”

Sherlock Holmes closed his eyes and placed his elbows upon the

arms of his chair, with his finger-tips together. “The ideal reasoner,” he

remarked, “would, [225] when

he had once been shown a single fact in all its bearings, deduce from it not only all the

chain of events which led up to it but also all the results which would follow from it. As

Cuvier could correctly describe a whole animal by the contemplation of a single bone, so

the observer who has thoroughly understood one link in a series of incidents should be

able to accurately state all the other ones, both before and after. We have not yet

grasped the results which the reason alone can attain to. Problems may be solved in the

study which have baffled all those who have sought a solution by the aid of their senses.

To carry the art, however, to its highest pitch, it is necessary that the reasoner should

be able to utilize all the facts which have come to his knowledge; and this in itself

implies, as you will readily see, a possession of all knowledge, which, even in these days

of free education and encyclopaedias, is a somewhat rare accomplishment. It is not so

impossible, however, that a man should possess all knowledge which is likely to be useful

to him in his work, and this I have endeavoured in my case to do. If I remember rightly,

you on one occasion, in the early days of our friendship, defined my limits in a very

precise fashion.” Sherlock Holmes closed his eyes and placed his elbows upon the

arms of his chair, with his finger-tips together. “The ideal reasoner,” he

remarked, “would, [225] when

he had once been shown a single fact in all its bearings, deduce from it not only all the

chain of events which led up to it but also all the results which would follow from it. As

Cuvier could correctly describe a whole animal by the contemplation of a single bone, so

the observer who has thoroughly understood one link in a series of incidents should be

able to accurately state all the other ones, both before and after. We have not yet

grasped the results which the reason alone can attain to. Problems may be solved in the

study which have baffled all those who have sought a solution by the aid of their senses.

To carry the art, however, to its highest pitch, it is necessary that the reasoner should

be able to utilize all the facts which have come to his knowledge; and this in itself

implies, as you will readily see, a possession of all knowledge, which, even in these days

of free education and encyclopaedias, is a somewhat rare accomplishment. It is not so

impossible, however, that a man should possess all knowledge which is likely to be useful

to him in his work, and this I have endeavoured in my case to do. If I remember rightly,

you on one occasion, in the early days of our friendship, defined my limits in a very

precise fashion.”

“Yes,” I answered, laughing. “It was a singular

document. Philosophy, astronomy, and politics were marked at zero, I remember. Botany

variable, geology profound as regards the mud-stains from any region within fifty miles of

town, chemistry eccentric, anatomy unsystematic, sensational literature and crime records

unique, violin-player, boxer, swordsman, lawyer, and self-poisoner by cocaine and tobacco.

Those, I think, were the main points of my analysis.” “Yes,” I answered, laughing. “It was a singular

document. Philosophy, astronomy, and politics were marked at zero, I remember. Botany

variable, geology profound as regards the mud-stains from any region within fifty miles of

town, chemistry eccentric, anatomy unsystematic, sensational literature and crime records

unique, violin-player, boxer, swordsman, lawyer, and self-poisoner by cocaine and tobacco.

Those, I think, were the main points of my analysis.”

Holmes grinned at the last item. “Well,” he said,

“I say now, as I said then, that a man should keep his little brain-attic stocked

with all the furniture that he is likely to use, and the rest he can put away in the

lumber-room of his library, where he can get it if he wants it. Now, for such a case as

the one which has been submitted to us to-night, we need certainly to muster all our

resources. Kindly hand me down the letter K of the American Encyclopaedia which stands

upon the shelf beside you. Thank you. Now let us consider the situation and see what may

be deduced from it. In the first place, we may start with a strong presumption that

Colonel Openshaw had some very strong reason for leaving America. Men at his time of life

do not change all their habits and exchange willingly the charming climate of Florida for

the lonely life of an English provincial town. His extreme love of solitude in England

suggests the idea that he was in fear of someone or something, so we may assume as a

working hypothesis that it was fear of someone or something which drove him from America.

As to what it was he feared, we can only deduce that by considering the formidable letters

which were received by himself and his successors. Did you remark the postmarks of those

letters?” Holmes grinned at the last item. “Well,” he said,

“I say now, as I said then, that a man should keep his little brain-attic stocked

with all the furniture that he is likely to use, and the rest he can put away in the

lumber-room of his library, where he can get it if he wants it. Now, for such a case as

the one which has been submitted to us to-night, we need certainly to muster all our

resources. Kindly hand me down the letter K of the American Encyclopaedia which stands

upon the shelf beside you. Thank you. Now let us consider the situation and see what may

be deduced from it. In the first place, we may start with a strong presumption that

Colonel Openshaw had some very strong reason for leaving America. Men at his time of life

do not change all their habits and exchange willingly the charming climate of Florida for

the lonely life of an English provincial town. His extreme love of solitude in England

suggests the idea that he was in fear of someone or something, so we may assume as a

working hypothesis that it was fear of someone or something which drove him from America.

As to what it was he feared, we can only deduce that by considering the formidable letters

which were received by himself and his successors. Did you remark the postmarks of those

letters?”

“The first was from Pondicherry, the second from Dundee,

and the third from London.” “The first was from Pondicherry, the second from Dundee,

and the third from London.”

“From East London. What do you deduce from that?” “From East London. What do you deduce from that?”

“They are all seaports. That the writer was on board of a

ship.” “They are all seaports. That the writer was on board of a

ship.”

“Excellent. We have already a clue. There can be no doubt

that the probability–the strong probability–is that the writer was on board of a

ship. And now let us consider another point. In the case of Pondicherry, seven weeks

elapsed between the threat and its fulfillment, in Dundee it was only some three or four

days. Does that suggest anything?” “Excellent. We have already a clue. There can be no doubt

that the probability–the strong probability–is that the writer was on board of a

ship. And now let us consider another point. In the case of Pondicherry, seven weeks

elapsed between the threat and its fulfillment, in Dundee it was only some three or four

days. Does that suggest anything?”

“A greater distance to travel.” “A greater distance to travel.”

“But the letter had also a greater distance to

come.” “But the letter had also a greater distance to

come.”

[226] “Then

I do not see the point.” [226] “Then

I do not see the point.”

“There is at least a presumption that the vessel in which

the man or men are is a sailing-ship. It looks as if they always sent their singular

warning or token before them when starting upon their mission. You see how quickly the

deed followed the sign when it came from Dundee. If they had come from Pondicherry in a

steamer they would have arrived almost as soon as their letter. But, as a matter of fact,

seven weeks elapsed. I think that those seven weeks represented the difference between the

mail-boat which brought the letter and the sailing vessel which brought the writer.” “There is at least a presumption that the vessel in which

the man or men are is a sailing-ship. It looks as if they always sent their singular

warning or token before them when starting upon their mission. You see how quickly the

deed followed the sign when it came from Dundee. If they had come from Pondicherry in a

steamer they would have arrived almost as soon as their letter. But, as a matter of fact,

seven weeks elapsed. I think that those seven weeks represented the difference between the

mail-boat which brought the letter and the sailing vessel which brought the writer.”

“It is possible.” “It is possible.”

“More than that. It is probable. And now you see the

deadly urgency of this new case, and why I urged young Openshaw to caution. The blow has

always fallen at the end of the time which it would take the senders to travel the

distance. But this one comes from London, and therefore we cannot count upon delay.” “More than that. It is probable. And now you see the

deadly urgency of this new case, and why I urged young Openshaw to caution. The blow has

always fallen at the end of the time which it would take the senders to travel the

distance. But this one comes from London, and therefore we cannot count upon delay.”

“Good God!” I cried. “What can it mean, this

relentless persecution?” “Good God!” I cried. “What can it mean, this

relentless persecution?”

“The papers which Openshaw carried are obviously of vital

importance to the person or persons in the sailing-ship. I think that it is quite clear

that there must be more than one of them. A single man could not have carried out two

deaths in such a way as to deceive a coroner’s jury. There must have been several in

it, and they must have been men of resource and determination. Their papers they mean to

have, be the holder of them who it may. In this way you see K. K. K. ceases to be the

initials of an individual and becomes the badge of a society.” “The papers which Openshaw carried are obviously of vital

importance to the person or persons in the sailing-ship. I think that it is quite clear

that there must be more than one of them. A single man could not have carried out two

deaths in such a way as to deceive a coroner’s jury. There must have been several in

it, and they must have been men of resource and determination. Their papers they mean to

have, be the holder of them who it may. In this way you see K. K. K. ceases to be the

initials of an individual and becomes the badge of a society.”

“But of what society?” “But of what society?”

“Have you never–” said Sherlock Holmes, bending

forward and sinking his voice–“have you never heard of the Ku Klux Klan?” “Have you never–” said Sherlock Holmes, bending

forward and sinking his voice–“have you never heard of the Ku Klux Klan?”

“I never have.” “I never have.”

Holmes turned over the leaves of the book upon his knee.

“Here it is,” said he presently: Holmes turned over the leaves of the book upon his knee.

“Here it is,” said he presently:

“Ku Klux Klan. A name derived from the fanciful

resemblance to the sound produced by cocking a rifle. This terrible secret society was

formed by some ex-Confederate soldiers in the Southern states after the Civil War, and it

rapidly formed local branches in different parts of the country, notably in Tennessee,

Louisiana, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Its power was used for political purposes,

principally for the terrorizing of the negro voters and the murdering and driving from the

country of those who were opposed to its views. Its outrages were usually preceded by a

warning sent to the marked man in some fantastic but generally recognized shape–a

sprig of oak-leaves in some parts, melon seeds or orange pips in others. On receiving this

the victim might either openly abjure his former ways, or might fly from the country. If

he braved the matter out, death would unfailingly come upon him, and usually in some

strange and unforeseen manner. So perfect was the organization of the society, and so

systematic its methods, that there is hardly a case upon record where any man succeeded in

braving it with impunity, or in which any of its outrages were traced home to the

perpetrators. For some years the organization flourished in spite of the efforts of the

United States government and of the better classes of the community in the South.

Eventually, in the year 1869, the movement rather suddenly collapsed, although there have

been sporadic outbreaks of the same sort since that date. “Ku Klux Klan. A name derived from the fanciful

resemblance to the sound produced by cocking a rifle. This terrible secret society was

formed by some ex-Confederate soldiers in the Southern states after the Civil War, and it

rapidly formed local branches in different parts of the country, notably in Tennessee,

Louisiana, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Its power was used for political purposes,

principally for the terrorizing of the negro voters and the murdering and driving from the

country of those who were opposed to its views. Its outrages were usually preceded by a

warning sent to the marked man in some fantastic but generally recognized shape–a

sprig of oak-leaves in some parts, melon seeds or orange pips in others. On receiving this

the victim might either openly abjure his former ways, or might fly from the country. If

he braved the matter out, death would unfailingly come upon him, and usually in some

strange and unforeseen manner. So perfect was the organization of the society, and so

systematic its methods, that there is hardly a case upon record where any man succeeded in

braving it with impunity, or in which any of its outrages were traced home to the

perpetrators. For some years the organization flourished in spite of the efforts of the

United States government and of the better classes of the community in the South.

Eventually, in the year 1869, the movement rather suddenly collapsed, although there have

been sporadic outbreaks of the same sort since that date.

[227] “You

will observe,” said Holmes, laying down the volume, “that the sudden breaking up

of the society was coincident with the disappearance of Openshaw from America with their

papers. It may well have been cause and effect. It is no wonder that he and his family

have some of the more implacable spirits upon their track. You can understand that this

register and diary may implicate some of the first men in the South, and that there may be

many who will not sleep easy at night until it is recovered.” [227] “You

will observe,” said Holmes, laying down the volume, “that the sudden breaking up

of the society was coincident with the disappearance of Openshaw from America with their

papers. It may well have been cause and effect. It is no wonder that he and his family

have some of the more implacable spirits upon their track. You can understand that this

register and diary may implicate some of the first men in the South, and that there may be

many who will not sleep easy at night until it is recovered.”

“Then the page we have seen– –” “Then the page we have seen– –”

“Is such as we might expect. It ran, if I remember right,

‘sent the pips to A, B, and C’–that is, sent the society’s warning to

them. Then there are successive entries that A and B cleared, or left the country, and

finally that C was visited, with, I fear, a sinister result for C. Well, I think, Doctor,

that we may let some light into this dark place, and I believe that the only chance young

Openshaw has in the meantime is to do what I have told him. There is nothing more to be

said or to be done to-night, so hand me over my violin and let us try to forget for half

an hour the miserable weather and the still more miserable ways of our fellowmen.” “Is such as we might expect. It ran, if I remember right,

‘sent the pips to A, B, and C’–that is, sent the society’s warning to

them. Then there are successive entries that A and B cleared, or left the country, and

finally that C was visited, with, I fear, a sinister result for C. Well, I think, Doctor,

that we may let some light into this dark place, and I believe that the only chance young

Openshaw has in the meantime is to do what I have told him. There is nothing more to be

said or to be done to-night, so hand me over my violin and let us try to forget for half

an hour the miserable weather and the still more miserable ways of our fellowmen.”

It had cleared in the morning, and the sun was shining with

a subdued brightness through the dim veil which hangs over the great city. Sherlock Holmes

was already at breakfast when I came down. It had cleared in the morning, and the sun was shining with

a subdued brightness through the dim veil which hangs over the great city. Sherlock Holmes

was already at breakfast when I came down.

“You will excuse me for not waiting for you,” said

he; “I have, I foresee, a very busy day before me in looking into this case of young

Openshaw’s.” “You will excuse me for not waiting for you,” said

he; “I have, I foresee, a very busy day before me in looking into this case of young

Openshaw’s.”

“What steps will you take?” I asked. “What steps will you take?” I asked.

“It will very much depend upon the results of my first

inquiries. I may have to go down to Horsham, after all.” “It will very much depend upon the results of my first

inquiries. I may have to go down to Horsham, after all.”

“You will not go there first?” “You will not go there first?”

“No, I shall commence with the City. Just ring the bell

and the maid will bring up your coffee.” “No, I shall commence with the City. Just ring the bell

and the maid will bring up your coffee.”

As I waited, I lifted the unopened newspaper from the table

and glanced my eye over it. It rested upon a heading which sent a chill to my heart. As I waited, I lifted the unopened newspaper from the table

and glanced my eye over it. It rested upon a heading which sent a chill to my heart.

“Holmes,” I cried, “you are too late.” “Holmes,” I cried, “you are too late.”

“Ah!” said he, laying down his cup, “I feared

as much. How was it done?” He spoke calmly, but I could see that he was deeply moved. “Ah!” said he, laying down his cup, “I feared

as much. How was it done?” He spoke calmly, but I could see that he was deeply moved.

“My eye caught the name of Openshaw, and the heading

‘Tragedy Near Waterloo Bridge.’ Here is the account: “My eye caught the name of Openshaw, and the heading

‘Tragedy Near Waterloo Bridge.’ Here is the account:

“Between nine and ten last night Police-Constable Cook,

of the H Division, on duty near Waterloo Bridge, heard a cry for help and a splash in the

water. The night, however, was extremely dark and stormy, so that, in spite of the help of

several passers-by, it was quite impossible to effect a rescue. The alarm, however, was

given, and, by the aid of the water-police, the body was eventually recovered. It proved

to be that of a young gentleman whose name, as it appears from an envelope which was found

in his pocket, was John Openshaw, and whose residence is near Horsham. It is conjectured

that he may have been hurrying down to catch the last train from Waterloo Station, and

that in his haste and the extreme darkness he missed his path and walked over the edge of

one of the small landing-places for river steamboats. The body exhibited no traces of

violence, and there can be no doubt that the deceased had been the victim of an

unfortunate accident, which [228] should

have the effect of calling the attention of the authorities to the condition of the

riverside landing-stages.” “Between nine and ten last night Police-Constable Cook,

of the H Division, on duty near Waterloo Bridge, heard a cry for help and a splash in the

water. The night, however, was extremely dark and stormy, so that, in spite of the help of

several passers-by, it was quite impossible to effect a rescue. The alarm, however, was

given, and, by the aid of the water-police, the body was eventually recovered. It proved

to be that of a young gentleman whose name, as it appears from an envelope which was found

in his pocket, was John Openshaw, and whose residence is near Horsham. It is conjectured

that he may have been hurrying down to catch the last train from Waterloo Station, and

that in his haste and the extreme darkness he missed his path and walked over the edge of

one of the small landing-places for river steamboats. The body exhibited no traces of

violence, and there can be no doubt that the deceased had been the victim of an

unfortunate accident, which [228] should

have the effect of calling the attention of the authorities to the condition of the

riverside landing-stages.”

We sat in silence for some minutes, Holmes more depressed

and shaken than I had ever seen him. We sat in silence for some minutes, Holmes more depressed

and shaken than I had ever seen him.

“That hurts my pride, Watson,” he said at last.

“It is a petty feeling, no doubt, but it hurts my pride. It becomes a personal matter

with me now, and, if God sends me health, I shall set my hand upon this gang. That he

should come to me for help, and that I should send him away to his death–

–!” He sprang from his chair and paced about the room in uncontrollable

agitation, with a flush upon his sallow cheeks and a nervous clasping and unclasping of

his long thin hands. “That hurts my pride, Watson,” he said at last.

“It is a petty feeling, no doubt, but it hurts my pride. It becomes a personal matter

with me now, and, if God sends me health, I shall set my hand upon this gang. That he

should come to me for help, and that I should send him away to his death–

–!” He sprang from his chair and paced about the room in uncontrollable

agitation, with a flush upon his sallow cheeks and a nervous clasping and unclasping of

his long thin hands.

“They must be cunning devils,” he exclaimed at

last. “How could they have decoyed him down there? The Embankment is not on the

direct line to the station. The bridge, no doubt, was too crowded, even on such a night,

for their purpose. Well, Watson, we shall see who will win in the long run. I am going out

now!” “They must be cunning devils,” he exclaimed at

last. “How could they have decoyed him down there? The Embankment is not on the

direct line to the station. The bridge, no doubt, was too crowded, even on such a night,

for their purpose. Well, Watson, we shall see who will win in the long run. I am going out

now!”

“To the police?” “To the police?”

“No; I shall be my own police. When I have spun the web

they may take the flies, but not before.” “No; I shall be my own police. When I have spun the web

they may take the flies, but not before.”

All day I was engaged in my professional work, and it was late

in the evening before I returned to Baker Street. Sherlock Holmes had not come back yet.

It was nearly ten o’clock before he entered, looking pale and worn. He walked up to

the sideboard, and tearing a piece from the loaf he devoured it voraciously, washing it

down with a long draught of water. All day I was engaged in my professional work, and it was late

in the evening before I returned to Baker Street. Sherlock Holmes had not come back yet.

It was nearly ten o’clock before he entered, looking pale and worn. He walked up to

the sideboard, and tearing a piece from the loaf he devoured it voraciously, washing it

down with a long draught of water.

“You are hungry,” I remarked. “You are hungry,” I remarked.

“Starving. It had escaped my memory. I have had nothing

since breakfast.” “Starving. It had escaped my memory. I have had nothing

since breakfast.”

“Nothing?” “Nothing?”

“Not a bite. I had no time to think of it.” “Not a bite. I had no time to think of it.”

“And how have you succeeded?” “And how have you succeeded?”

“Well.” “Well.”

“You have a clue?” “You have a clue?”

“I have them in the hollow of my hand. Young Openshaw

shall not long remain unavenged. Why, Watson, let us put their own devilish trade-mark

upon them. It is well thought of!” “I have them in the hollow of my hand. Young Openshaw

shall not long remain unavenged. Why, Watson, let us put their own devilish trade-mark

upon them. It is well thought of!”

“What do you mean?” “What do you mean?”

He took an orange from the cupboard, and tearing it to pieces

he squeezed out the pips upon the table. Of these he took five and thrust them into an

envelope. On the inside of the flap he wrote “S. H. for J. O.” Then he sealed it

and addressed it to “Captain James Calhoun, Bark Lone Star, Savannah,

Georgia.” He took an orange from the cupboard, and tearing it to pieces

he squeezed out the pips upon the table. Of these he took five and thrust them into an

envelope. On the inside of the flap he wrote “S. H. for J. O.” Then he sealed it

and addressed it to “Captain James Calhoun, Bark Lone Star, Savannah,

Georgia.”

“That will await him when he enters port,” said he,

chuckling. “It may give him a sleepless night. He will find it as sure a precursor of

his fate as Openshaw did before him.” “That will await him when he enters port,” said he,

chuckling. “It may give him a sleepless night. He will find it as sure a precursor of

his fate as Openshaw did before him.”

“And who is this Captain Calhoun?” “And who is this Captain Calhoun?”

“The leader of the gang. I shall have the others, but he

first.” “The leader of the gang. I shall have the others, but he

first.”

“How did you trace it, then?” “How did you trace it, then?”

He took a large sheet of paper from his pocket, all covered

with dates and names. He took a large sheet of paper from his pocket, all covered

with dates and names.

“I have spent the whole day,” said he, “over

Lloyd’s registers and files of the old papers, following the future career of every

vessel which touched at Pondicherry in January and February in ’83. There were

thirty-six ships of fair tonnage which were reported there during those months. Of these,

one, the Lone Star, instantly [229]

attracted my attention, since, although it was reported as having cleared

from London, the name is that which is given to one of the states of the Union.” “I have spent the whole day,” said he, “over

Lloyd’s registers and files of the old papers, following the future career of every

vessel which touched at Pondicherry in January and February in ’83. There were

thirty-six ships of fair tonnage which were reported there during those months. Of these,

one, the Lone Star, instantly [229]

attracted my attention, since, although it was reported as having cleared

from London, the name is that which is given to one of the states of the Union.”

“Texas, I think.” “Texas, I think.”

“I was not and am not sure which; but I knew that the

ship must have an American origin.” “I was not and am not sure which; but I knew that the

ship must have an American origin.”

“What then?” “What then?”

“I searched the Dundee records, and when I found that the

bark Lone Star was there in January, ’85, my suspicion became a certainty. I

then inquired as to the vessels which lay at present in the port of London.” “I searched the Dundee records, and when I found that the

bark Lone Star was there in January, ’85, my suspicion became a certainty. I

then inquired as to the vessels which lay at present in the port of London.”

“Yes?” “Yes?”

“The Lone Star had arrived here last week. I

went down to the Albert Dock and found that she had been taken down the river by the early

tide this morning, homeward bound to Savannah. I wired to Gravesend and learned that she

had passed some time ago, and as the wind is easterly I have no doubt that she is now past

the Goodwins and not very far from the Isle of Wight.” “The Lone Star had arrived here last week. I

went down to the Albert Dock and found that she had been taken down the river by the early

tide this morning, homeward bound to Savannah. I wired to Gravesend and learned that she

had passed some time ago, and as the wind is easterly I have no doubt that she is now past

the Goodwins and not very far from the Isle of Wight.”

“What will you do, then?” “What will you do, then?”

“Oh, I have my hand upon him. He and the two mates, are,

as I learn, the only native-born Americans in the ship. The others are Finns and Germans.

I know, also, that they were all three away from the ship last night. I had it from the

stevedore who has been loading their cargo. By the time that their sailing-ship reaches

Savannah the mail-boat will have carried this letter, and the cable will have informed the

police of Savannah that these three gentlemen are badly wanted here upon a charge of

murder.” “Oh, I have my hand upon him. He and the two mates, are,

as I learn, the only native-born Americans in the ship. The others are Finns and Germans.

I know, also, that they were all three away from the ship last night. I had it from the

stevedore who has been loading their cargo. By the time that their sailing-ship reaches

Savannah the mail-boat will have carried this letter, and the cable will have informed the

police of Savannah that these three gentlemen are badly wanted here upon a charge of

murder.”

There is ever a flaw, however, in the best laid of human

plans, and the murderers of John Openshaw were never to receive the orange pips which

would show them that another, as cunning and as resolute as themselves, was upon their

track. Very long and very severe were the equinoctial gales that year. We waited long for

news of the Lone Star of Savannah, but none ever reached us. We did at last hear

that somewhere far out in the Atlantic a shattered stern-post of the boat was seen

swinging in the trough of a wave, with the letters “L. S.” carved upon it, and

that is all which we shall ever know of the fate of the Lone Star. There is ever a flaw, however, in the best laid of human

plans, and the murderers of John Openshaw were never to receive the orange pips which

would show them that another, as cunning and as resolute as themselves, was upon their

track. Very long and very severe were the equinoctial gales that year. We waited long for

news of the Lone Star of Savannah, but none ever reached us. We did at last hear

that somewhere far out in the Atlantic a shattered stern-post of the boat was seen

swinging in the trough of a wave, with the letters “L. S.” carved upon it, and

that is all which we shall ever know of the fate of the Lone Star.

|

![]() [218] The

year ’87 furnished us with a long series of cases of greater or less interest, of

which I retain the records. Among my headings under this one twelve months I find an

account of the adventure of the Paradol Chamber, of the Amateur Mendicant Society, who

held a luxurious club in the lower vault of a furniture warehouse, of the facts connected

with the loss of the British bark Sophy Anderson, of the singular adventures of the Grice

Patersons in the island of Uffa, and finally of the Camberwell poisoning case. In the

latter, as may be remembered, Sherlock Holmes was able, by winding up the dead man’s

watch, to prove that it had been wound up two hours before, and that therefore the

deceased had gone to bed within that time–a deduction which was of the greatest

importance in clearing up the case. All these I may sketch out at some future date, but

none of them present such singular features as the strange train of circumstances which I

have now taken up my pen to describe.

[218] The

year ’87 furnished us with a long series of cases of greater or less interest, of

which I retain the records. Among my headings under this one twelve months I find an

account of the adventure of the Paradol Chamber, of the Amateur Mendicant Society, who

held a luxurious club in the lower vault of a furniture warehouse, of the facts connected

with the loss of the British bark Sophy Anderson, of the singular adventures of the Grice

Patersons in the island of Uffa, and finally of the Camberwell poisoning case. In the

latter, as may be remembered, Sherlock Holmes was able, by winding up the dead man’s

watch, to prove that it had been wound up two hours before, and that therefore the

deceased had gone to bed within that time–a deduction which was of the greatest

importance in clearing up the case. All these I may sketch out at some future date, but

none of them present such singular features as the strange train of circumstances which I

have now taken up my pen to describe.![]() It was in the latter days of September, and the equinoctial

gales had set in with exceptional violence. All day the wind had screamed and the rain had

beaten against the windows, so that even here in the heart of great, hand-made London we

were forced to raise our minds for the instant from the routine of life, and to recognize

the presence of those great elemental forces which shriek at mankind through the bars of

his civilization, like untamed beasts in a cage. As evening drew in, the storm grew higher

and louder, and the wind cried and sobbed like a child in the chimney. Sherlock Holmes sat

moodily at one side of the fireplace cross-indexing his records of crime, while I at the

other was deep in one of Clark Russell’s fine sea-stories until the howl of the gale

from without seemed to blend with the text, and the splash of the rain to lengthen out

into the long swash of the sea waves. My wife was on a visit to her mother’s, and for

a few days I was a dweller once more in my old quarters at Baker Street.

It was in the latter days of September, and the equinoctial