|

|

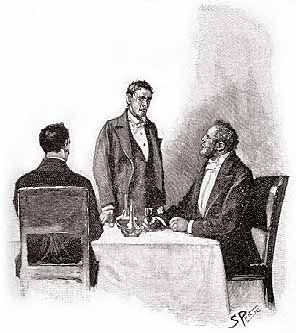

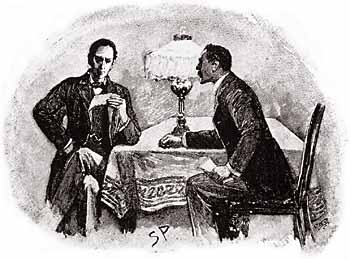

“One evening, shortly after my arrival, we were sitting

over a glass of port after dinner, when young Trevor began to talk about those habits of

observation and inference which I had already formed into a system, although I had not yet

appreciated the part which they were to play in my life. The old man evidently thought

that his son was exaggerating in his description of one or two trivial feats which I had

performed. “One evening, shortly after my arrival, we were sitting

over a glass of port after dinner, when young Trevor began to talk about those habits of

observation and inference which I had already formed into a system, although I had not yet

appreciated the part which they were to play in my life. The old man evidently thought

that his son was exaggerating in his description of one or two trivial feats which I had

performed.

“ ‘Come, now, Mr. Holmes,’ said he, laughing

good-humouredly. ‘I’m an excellent subject, if you can deduce anything from

me.’ “ ‘Come, now, Mr. Holmes,’ said he, laughing

good-humouredly. ‘I’m an excellent subject, if you can deduce anything from

me.’

“ ‘I fear there is not very much,’ I answered.

‘I might suggest that you have gone about in fear of some personal attack within the

last twelvemonth.’ “ ‘I fear there is not very much,’ I answered.

‘I might suggest that you have gone about in fear of some personal attack within the

last twelvemonth.’

“The laugh faded from his lips, and he stared at me in

great surprise. “The laugh faded from his lips, and he stared at me in

great surprise.

“ ‘Well, that’s true enough,’ said he.

‘You know, Victor,’ turning to his son, ‘when we broke up that poaching

gang they swore to knife us, and Sir Edward Holly has actually been attacked. I’ve

always been on my guard since then, though I have no idea how you know it.’ “ ‘Well, that’s true enough,’ said he.

‘You know, Victor,’ turning to his son, ‘when we broke up that poaching

gang they swore to knife us, and Sir Edward Holly has actually been attacked. I’ve

always been on my guard since then, though I have no idea how you know it.’

“ ‘You have a very handsome stick,’ I answered.

‘By the inscription I observed that you had not had it more than a year. But you have

taken some pains to bore the head of it and pour melted lead into the hole so as to make

it a formidable weapon. I argued that you would not take such precautions unless you had

some danger to fear.’ “ ‘You have a very handsome stick,’ I answered.

‘By the inscription I observed that you had not had it more than a year. But you have

taken some pains to bore the head of it and pour melted lead into the hole so as to make

it a formidable weapon. I argued that you would not take such precautions unless you had

some danger to fear.’

“ ‘Anything else?’ he asked, smiling. “ ‘Anything else?’ he asked, smiling.

“ ‘You have boxed a good deal in your youth.’ “ ‘You have boxed a good deal in your youth.’

“ ‘Right again. How did you know it? Is my nose

knocked a little out of the straight?’ “ ‘Right again. How did you know it? Is my nose

knocked a little out of the straight?’

“ ‘No,’ said I. ‘It is your ears. They

have the peculiar flattening and thickening which marks the boxing man.’ “ ‘No,’ said I. ‘It is your ears. They

have the peculiar flattening and thickening which marks the boxing man.’

“ ‘Anything else?’ “ ‘Anything else?’

“ ‘You have done a good deal of digging by your

callosities.’ “ ‘You have done a good deal of digging by your

callosities.’

“ ‘Made all my money at the gold fields.’ “ ‘Made all my money at the gold fields.’

“ ‘You have been in New Zealand.’ “ ‘You have been in New Zealand.’

“ ‘Right again.’ “ ‘Right again.’

“ ‘You have visited Japan.’ “ ‘You have visited Japan.’

“ ‘Quite true.’ “ ‘Quite true.’

“ ‘And you have been most intimately associated with

someone whose initials were J. A., and whom you afterwards were eager to entirely

forget.’ “ ‘And you have been most intimately associated with

someone whose initials were J. A., and whom you afterwards were eager to entirely

forget.’

“Mr. Trevor stood slowly up, fixed his large blue eyes

upon me with a strange wild stare, and then pitched forward, with his face among the

nutshells which strewed the cloth, in a dead faint. “Mr. Trevor stood slowly up, fixed his large blue eyes

upon me with a strange wild stare, and then pitched forward, with his face among the

nutshells which strewed the cloth, in a dead faint.

“You can imagine, Watson, how shocked both his son and I

were. His attack did not last long, however, for when we undid his collar and sprinkled

the water from one of the finger-glasses over his face, he gave a gasp or two and sat up. “You can imagine, Watson, how shocked both his son and I

were. His attack did not last long, however, for when we undid his collar and sprinkled

the water from one of the finger-glasses over his face, he gave a gasp or two and sat up.

[376] “

‘Ah, boys,’ said he, forcing a smile, ‘I hope I haven’t frightened

you. Strong as I look, there is a weak place in my heart, and it does not take much to

knock me over. I don’t know how you manage this, Mr. Holmes, but it seems to me that

all the detectives of fact and of fancy would be children in your hands. That’s your

line of life, sir, and you may take the word of a man who has seen something of the

world.’ [376] “

‘Ah, boys,’ said he, forcing a smile, ‘I hope I haven’t frightened

you. Strong as I look, there is a weak place in my heart, and it does not take much to

knock me over. I don’t know how you manage this, Mr. Holmes, but it seems to me that

all the detectives of fact and of fancy would be children in your hands. That’s your

line of life, sir, and you may take the word of a man who has seen something of the

world.’

“And that recommendation, with the exaggerated estimate

of my ability with which he prefaced it, was, if you will believe me, Watson, the very

first thing which ever made me feel that a profession might be made out of what had up to

that time been the merest hobby. At the moment, however, I was too much concerned at the

sudden illness of my host to think of anything else. “And that recommendation, with the exaggerated estimate

of my ability with which he prefaced it, was, if you will believe me, Watson, the very

first thing which ever made me feel that a profession might be made out of what had up to

that time been the merest hobby. At the moment, however, I was too much concerned at the

sudden illness of my host to think of anything else.

“ ‘I hope that I have said nothing to pain

you?’ said I. “ ‘I hope that I have said nothing to pain

you?’ said I.

“ ‘Well, you certainly touched upon rather a tender

point. Might I ask how you know, and how much you know?’ He spoke now in a

half-jesting fashion, but a look of terror still lurked at the back of his eyes. “ ‘Well, you certainly touched upon rather a tender

point. Might I ask how you know, and how much you know?’ He spoke now in a

half-jesting fashion, but a look of terror still lurked at the back of his eyes.

“ ‘It is simplicity itself,’ said I. ‘When

you bared your arm to draw that fish into the boat I saw that J. A. had been tattooed in

the bend of the elbow. The letters were still legible, but it was perfectly clear from

their blurred appearance, and from the staining of the skin round them, that efforts had

been made to obliterate them. It was obvious, then, that those initials had once been very

familiar to you, and that you had afterwards wished to forget them.’ “ ‘It is simplicity itself,’ said I. ‘When

you bared your arm to draw that fish into the boat I saw that J. A. had been tattooed in

the bend of the elbow. The letters were still legible, but it was perfectly clear from

their blurred appearance, and from the staining of the skin round them, that efforts had

been made to obliterate them. It was obvious, then, that those initials had once been very

familiar to you, and that you had afterwards wished to forget them.’

“ ‘What an eye you have!’ he cried with a sigh

of relief. ‘It is just as you say. But we won’t talk of it. Of all ghosts the

ghosts of our old loves are the worst. Come into the billiard-room and have a quiet

cigar.’ “ ‘What an eye you have!’ he cried with a sigh

of relief. ‘It is just as you say. But we won’t talk of it. Of all ghosts the

ghosts of our old loves are the worst. Come into the billiard-room and have a quiet

cigar.’ “From that day, amid all his cordiality,

there was always a touch of suspicion in Mr. Trevor’s manner towards me. Even his son

remarked it. ‘You’ve given the governor such a turn,’ said he, ‘that

he’ll never be sure again of what you know and what you don’t know.’ He did

not mean to show it, I am sure, but it was so strongly in his mind that it peeped out at

every action. At last I became so convinced that I was causing him uneasiness that I drew

my visit to a close. On the very day, however, before I left, an incident occurred which

proved in the sequel to be of importance. “From that day, amid all his cordiality,

there was always a touch of suspicion in Mr. Trevor’s manner towards me. Even his son

remarked it. ‘You’ve given the governor such a turn,’ said he, ‘that

he’ll never be sure again of what you know and what you don’t know.’ He did

not mean to show it, I am sure, but it was so strongly in his mind that it peeped out at

every action. At last I became so convinced that I was causing him uneasiness that I drew

my visit to a close. On the very day, however, before I left, an incident occurred which

proved in the sequel to be of importance.

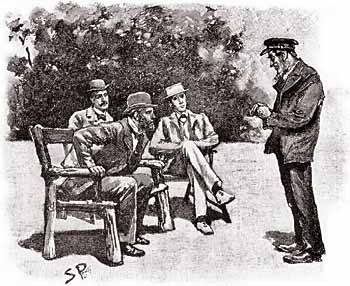

“We were sitting out upon the lawn on garden chairs, the

three of us, basking in the sun and admiring the view across the Broads, when a maid came

out to say that there was a man at the door who wanted to see Mr. Trevor. “We were sitting out upon the lawn on garden chairs, the

three of us, basking in the sun and admiring the view across the Broads, when a maid came

out to say that there was a man at the door who wanted to see Mr. Trevor.

“ ‘What is his name?’ asked my host. “ ‘What is his name?’ asked my host.

“ ‘He would not give any.’ “ ‘He would not give any.’

“ ‘What does he want, then?’ “ ‘What does he want, then?’

“ ‘He says that you know him, and that he only wants

a moment’s conversation.’ “ ‘He says that you know him, and that he only wants

a moment’s conversation.’

“ ‘Show him round here.’ An instant afterwards

there appeared a little wizened fellow with a cringing manner and a shambling style of

walking. He wore an open jacket, with a splotch of tar on the sleeve, a red-and-black

check shirt, dungaree trousers, and heavy boots badly worn. His face was thin and brown

and crafty, with a perpetual smile upon it, which showed an irregular line of yellow

teeth, and his crinkled hands were half closed in a way that is distinctive of sailors. As

he came slouching across the lawn I heard Mr. Trevor make a sort of hiccoughing noise in

his throat, and, jumping out of his chair, he ran into the house. He was back in a moment,

and I smelt a strong reek of brandy as he passed me. “ ‘Show him round here.’ An instant afterwards

there appeared a little wizened fellow with a cringing manner and a shambling style of

walking. He wore an open jacket, with a splotch of tar on the sleeve, a red-and-black

check shirt, dungaree trousers, and heavy boots badly worn. His face was thin and brown

and crafty, with a perpetual smile upon it, which showed an irregular line of yellow

teeth, and his crinkled hands were half closed in a way that is distinctive of sailors. As

he came slouching across the lawn I heard Mr. Trevor make a sort of hiccoughing noise in

his throat, and, jumping out of his chair, he ran into the house. He was back in a moment,

and I smelt a strong reek of brandy as he passed me.

[377] “

‘Well, my man,’ said he. ‘What can I do for you?’ [377] “

‘Well, my man,’ said he. ‘What can I do for you?’

“The sailor stood looking at him with puckered eyes, and

with the same loose-lipped smile upon his face. “The sailor stood looking at him with puckered eyes, and

with the same loose-lipped smile upon his face.

“ ‘You don’t know me?’ he asked. “ ‘You don’t know me?’ he asked.

“ ‘Why, dear me, it is surely Hudson,’ said Mr.

Trevor in a tone of surprise. “ ‘Why, dear me, it is surely Hudson,’ said Mr.

Trevor in a tone of surprise.

“ ‘Hudson it is, sir,’ said the seaman.

‘Why, it’s thirty year and more since I saw you last. Here you are in your

house, and me still picking my salt meat out of the harness cask.’ “ ‘Hudson it is, sir,’ said the seaman.

‘Why, it’s thirty year and more since I saw you last. Here you are in your

house, and me still picking my salt meat out of the harness cask.’

“ ‘Tut, you will find that I have not forgotten old

times,’ cried Mr. Trevor, and, walking towards the sailor, he said something in a low

voice. ‘Go into the kitchen,’ he continued out loud, ‘and you will get food

and drink. I have no doubt that I shall find you a situation.’ “ ‘Tut, you will find that I have not forgotten old

times,’ cried Mr. Trevor, and, walking towards the sailor, he said something in a low

voice. ‘Go into the kitchen,’ he continued out loud, ‘and you will get food

and drink. I have no doubt that I shall find you a situation.’

“ ‘Thank you, sir,’ said the seaman, touching

his forelock. ‘I’m just off a two-yearer in an eight-knot tramp, short-handed at

that, and I wants a rest. I thought I’d get it either with Mr. Beddoes or with

you.’ “ ‘Thank you, sir,’ said the seaman, touching

his forelock. ‘I’m just off a two-yearer in an eight-knot tramp, short-handed at

that, and I wants a rest. I thought I’d get it either with Mr. Beddoes or with

you.’

“ ‘Ah!’ cried Mr. Trevor. ‘You know where

Mr. Beddoes is?’ “ ‘Ah!’ cried Mr. Trevor. ‘You know where

Mr. Beddoes is?’

“ ‘Bless you, sir, I know where all my old friends

are,’ said the fellow with a sinister smile, and he slouched off after the maid to

the kitchen. Mr. Trevor mumbled something to us about having been shipmate with the man

when he was going back to the diggings, and then, leaving us on the lawn, he went indoors.

An hour later, when we entered the house, we found him stretched dead drunk upon the

dining-room sofa. The whole incident left a most ugly impression upon my mind, and I was

not sorry next day to leave Donnithorpe behind me, for I felt that my presence must be a

source of embarrassment to my friend. “ ‘Bless you, sir, I know where all my old friends

are,’ said the fellow with a sinister smile, and he slouched off after the maid to

the kitchen. Mr. Trevor mumbled something to us about having been shipmate with the man

when he was going back to the diggings, and then, leaving us on the lawn, he went indoors.

An hour later, when we entered the house, we found him stretched dead drunk upon the

dining-room sofa. The whole incident left a most ugly impression upon my mind, and I was

not sorry next day to leave Donnithorpe behind me, for I felt that my presence must be a

source of embarrassment to my friend.

“All this occurred during the first month of the long

vacation. I went up to my London rooms, where I spent seven weeks working out a few

experiments in organic chemistry. One day, however, when the autumn was far advanced and

the vacation drawing to a close, I received a telegram from my friend imploring me to

return to Donnithorpe, and saying that he was in great need of my advice and assistance.

Of course I dropped everything and set out for the North once more. “All this occurred during the first month of the long

vacation. I went up to my London rooms, where I spent seven weeks working out a few

experiments in organic chemistry. One day, however, when the autumn was far advanced and

the vacation drawing to a close, I received a telegram from my friend imploring me to

return to Donnithorpe, and saying that he was in great need of my advice and assistance.

Of course I dropped everything and set out for the North once more.

“He met me with the dog-cart at the station, and I saw at

a glance that the last two months had been very trying ones for him. He had grown thin and

careworn, and had lost the loud, cheery manner for which he had been remarkable. “He met me with the dog-cart at the station, and I saw at

a glance that the last two months had been very trying ones for him. He had grown thin and

careworn, and had lost the loud, cheery manner for which he had been remarkable.

“ ‘The governor is dying,’ were the first words

he said. “ ‘The governor is dying,’ were the first words

he said.

“ ‘Impossible!’ I cried. ‘What is the

matter?’ “ ‘Impossible!’ I cried. ‘What is the

matter?’

“ ‘Apoplexy. Nervous shock. He’s been on the

verge all day. I doubt if we shall find him alive.’ “ ‘Apoplexy. Nervous shock. He’s been on the

verge all day. I doubt if we shall find him alive.’

“I was, as you may think, Watson, horrified at this

unexpected news. “I was, as you may think, Watson, horrified at this

unexpected news.

“ ‘What has caused it?’ I asked. “ ‘What has caused it?’ I asked.

“ ‘Ah, that is the point. Jump in and we can talk it

over while we drive. You remember that fellow who came upon the evening before you left

us?’ “ ‘Ah, that is the point. Jump in and we can talk it

over while we drive. You remember that fellow who came upon the evening before you left

us?’

“ ‘Perfectly.’ “ ‘Perfectly.’

“ ‘Do you know who it was that we let into the house

that day?’ “ ‘Do you know who it was that we let into the house

that day?’

“ ‘I have no idea.’ “ ‘I have no idea.’

“ ‘It was the devil, Holmes,’ he cried. “ ‘It was the devil, Holmes,’ he cried.

“I stared at him in astonishment. “I stared at him in astonishment.

“ ‘Yes, it was the devil himself. We have not had a

peaceful hour since– not one. The governor has never held up his head from that

evening, and now the life [378] has

been crushed out of him and his heart broken, all through this accursed Hudson.’ “ ‘Yes, it was the devil himself. We have not had a

peaceful hour since– not one. The governor has never held up his head from that

evening, and now the life [378] has

been crushed out of him and his heart broken, all through this accursed Hudson.’

“ ‘What power had he, then?’ “ ‘What power had he, then?’

“ ‘Ah, that is what I would give so much to know.

The kindly, charitable good old governor–how could he have fallen into the clutches

of such a ruffian! But I am so glad that you have come, Holmes. I trust very much to your

judgment and discretion, and I know that you will advise me for the best.’ “ ‘Ah, that is what I would give so much to know.

The kindly, charitable good old governor–how could he have fallen into the clutches

of such a ruffian! But I am so glad that you have come, Holmes. I trust very much to your

judgment and discretion, and I know that you will advise me for the best.’

“We were dashing along the smooth white country road,

with the long stretch of the Broads in front of us glimmering in the red light of the

setting sun. From a grove upon our left I could already see the high chimneys and the

flagstaff which marked the squire’s dwelling. “We were dashing along the smooth white country road,

with the long stretch of the Broads in front of us glimmering in the red light of the

setting sun. From a grove upon our left I could already see the high chimneys and the

flagstaff which marked the squire’s dwelling.

“ ‘My father made the fellow gardener,’ said my

companion, ‘and then, as that did not satisfy him, he was promoted to be butler. The

house seemed to be at his mercy, and he wandered about and did what he chose in it. The

maids complained of his drunken habits and his vile language. The dad raised their wages

all round to recompense them for the annoyance. The fellow would take the boat and my

father’s best gun and treat himself to little shooting trips. And all this with such

a sneering, leering, insolent face that I would have knocked him down twenty times over if

he had been a man of my own age. I tell you, Holmes, I have had to keep a tight hold upon

myself all this time; and now I am asking myself whether, if I had let myself go a little

more, I might not have been a wiser man. “ ‘My father made the fellow gardener,’ said my

companion, ‘and then, as that did not satisfy him, he was promoted to be butler. The

house seemed to be at his mercy, and he wandered about and did what he chose in it. The

maids complained of his drunken habits and his vile language. The dad raised their wages

all round to recompense them for the annoyance. The fellow would take the boat and my

father’s best gun and treat himself to little shooting trips. And all this with such

a sneering, leering, insolent face that I would have knocked him down twenty times over if

he had been a man of my own age. I tell you, Holmes, I have had to keep a tight hold upon

myself all this time; and now I am asking myself whether, if I had let myself go a little

more, I might not have been a wiser man.

“ ‘Well, matters went from bad to worse with us, and

this animal Hudson became more and more intrusive, until at last, on his making some

insolent reply to my father in my presence one day, I took him by the shoulders and turned

him out of the room. He slunk away with a livid face and two venomous eyes which uttered

more threats than his tongue could do. I don’t know what passed between the poor dad

and him after that, but the dad came to me next day and asked me whether I would mind

apologizing to Hudson. I refused, as you can imagine, and asked my father how he could

allow such a wretch to take such liberties with himself and his household. “ ‘Well, matters went from bad to worse with us, and

this animal Hudson became more and more intrusive, until at last, on his making some

insolent reply to my father in my presence one day, I took him by the shoulders and turned

him out of the room. He slunk away with a livid face and two venomous eyes which uttered

more threats than his tongue could do. I don’t know what passed between the poor dad

and him after that, but the dad came to me next day and asked me whether I would mind

apologizing to Hudson. I refused, as you can imagine, and asked my father how he could

allow such a wretch to take such liberties with himself and his household.

“ ‘ “Ah, my boy,” said he, “it is all

very well to talk, but you don’t know how I am placed. But you shall know, Victor.

I’ll see that you shall know, come what may. You wouldn’t believe harm of your

poor old father, would you, lad?” He was very much moved and shut himself up in the

study all day, where I could see through the window that he was writing busily. “ ‘ “Ah, my boy,” said he, “it is all

very well to talk, but you don’t know how I am placed. But you shall know, Victor.

I’ll see that you shall know, come what may. You wouldn’t believe harm of your

poor old father, would you, lad?” He was very much moved and shut himself up in the

study all day, where I could see through the window that he was writing busily.

“ ‘That evening there came what seemed to me to be a

grand release, for Hudson told us that he was going to leave us. He walked into the

dining-room as we sat after dinner and announced his intention in the thick voice of a

half-drunken man. “ ‘That evening there came what seemed to me to be a

grand release, for Hudson told us that he was going to leave us. He walked into the

dining-room as we sat after dinner and announced his intention in the thick voice of a

half-drunken man.

“ ‘ “I’ve had enough of Norfolk,”

said he. “I’ll run down to Mr. Beddoes in Hampshire. He’ll be as glad to

see me as you were, I daresay.” “ ‘ “I’ve had enough of Norfolk,”

said he. “I’ll run down to Mr. Beddoes in Hampshire. He’ll be as glad to

see me as you were, I daresay.”

“ ‘ “You’re not going away in an unkind

spirit, Hudson, I hope,” said my father with a tameness which made my blood boil. “ ‘ “You’re not going away in an unkind

spirit, Hudson, I hope,” said my father with a tameness which made my blood boil.

“ ‘ “I’ve not had my

’pology,” said he sulkily, glancing in my direction. “ ‘ “I’ve not had my

’pology,” said he sulkily, glancing in my direction.

“ ‘ “Victor, you will acknowledge that you have

used this worthy fellow rather roughly,” said the dad, turning to me. “ ‘ “Victor, you will acknowledge that you have

used this worthy fellow rather roughly,” said the dad, turning to me.

“ ‘ “On the contrary, I think that we have both

shown extraordinary patience towards him,” I answered. “ ‘ “On the contrary, I think that we have both

shown extraordinary patience towards him,” I answered.

“ ‘ “Oh, you do, do you?” he snarled.

“Very good, mate. We’ll see about that!” “ ‘ “Oh, you do, do you?” he snarled.

“Very good, mate. We’ll see about that!”

“ ‘He slouched out of the room and half an hour

afterwards left the house, [379] leaving

my father in a state of pitiable nervousness. Night after night I heard him pacing his

room, and it was just as he was recovering his confidence that the blow did at last

fall.’ “ ‘He slouched out of the room and half an hour

afterwards left the house, [379] leaving

my father in a state of pitiable nervousness. Night after night I heard him pacing his

room, and it was just as he was recovering his confidence that the blow did at last

fall.’

“ ‘And how?’ I asked eagerly. “ ‘And how?’ I asked eagerly.

“ ‘In a most extraordinary fashion. A letter arrived

for my father yesterday evening, bearing the Fordingham postmark. My father read it,

clapped both his hands to his head, and began running round the room in little circles

like a man who has been driven out of his senses. When I at last drew him down on to the

sofa, his mouth and eyelids were all puckered on one side, and I saw that he had a stroke.

Dr. Fordham came over at once. We put him to bed, but the paralysis has spread, he has

shown no sign of returning consciousness, and I think that we shall hardly find him

alive.’ “ ‘In a most extraordinary fashion. A letter arrived

for my father yesterday evening, bearing the Fordingham postmark. My father read it,

clapped both his hands to his head, and began running round the room in little circles

like a man who has been driven out of his senses. When I at last drew him down on to the

sofa, his mouth and eyelids were all puckered on one side, and I saw that he had a stroke.

Dr. Fordham came over at once. We put him to bed, but the paralysis has spread, he has

shown no sign of returning consciousness, and I think that we shall hardly find him

alive.’

“ ‘You horrify me, Trevor!’ I cried. ‘What

then could have been in this letter to cause so dreadful a result?’ “ ‘You horrify me, Trevor!’ I cried. ‘What

then could have been in this letter to cause so dreadful a result?’

“ ‘Nothing. There lies the inexplicable part of it.

The message was absurd and trivial. Ah, my God, it is as I feared!’ “ ‘Nothing. There lies the inexplicable part of it.

The message was absurd and trivial. Ah, my God, it is as I feared!’

“As he spoke we came round the curve of the avenue and

saw in the fading light that every blind in the house had been drawn down. As we dashed up

to the door, my friend’s face convulsed with grief, a gentleman in black emerged from

it. “As he spoke we came round the curve of the avenue and

saw in the fading light that every blind in the house had been drawn down. As we dashed up

to the door, my friend’s face convulsed with grief, a gentleman in black emerged from

it.

“ ‘When did it happen, doctor?’ asked Trevor. “ ‘When did it happen, doctor?’ asked Trevor.

“ ‘Almost immediately after you left.’ “ ‘Almost immediately after you left.’

“ ‘Did he recover consciousness?’ “ ‘Did he recover consciousness?’

“ ‘For an instant before the end.’ “ ‘For an instant before the end.’

“ ‘Any message for me?’ “ ‘Any message for me?’

“ ‘Only that the papers were in the back drawer of

the Japanese cabinet.’ “ ‘Only that the papers were in the back drawer of

the Japanese cabinet.’

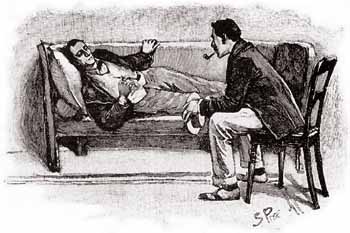

“My friend ascended with the doctor to the chamber of

death, while I remained in the study, turning the whole matter over and over in my head,

and feeling as sombre as ever I had done in my life. What was the past of this Trevor,

pugilist, traveller, and gold-digger, and how had he placed himself in the power of this

acid-faced seaman? Why, too, should he faint at an allusion to the half-effaced initials

upon his arm and die of fright when he had a letter from Fordingham? Then I remembered

that Fordingham was in Hampshire, and that this Mr. Beddoes, whom the seaman had gone to

visit and presumably to blackmail, had also been mentioned as living in Hampshire. The

letter, then, might either come from Hudson, the seaman, saying that he had betrayed the

guilty secret which appeared to exist, or it might come from Beddoes, warning an old

confederate that such a betrayal was imminent. So far it seemed clear enough. But then how

could this letter be trivial and grotesque, as described by the son? He must have misread

it. If so, it must have been one of those ingenious secret codes which mean one thing

while they seem to mean another. I must see this letter. If there was a hidden meaning in

it, I was confident that I could pluck it forth. For an hour I sat pondering over it in

the gloom, until at last a weeping maid brought in a lamp, and close at her heels came my

friend Trevor, pale but composed, with these very papers which lie upon my knee held in

his grasp. He sat down opposite to me, drew the lamp to the edge of the table, and handed

me a short note scribbled, as you see, upon a single sheet of gray paper. ‘The supply

of game for London is going steadily up,’ it ran. ‘Head-keeper Hudson, we

believe, has been now told to receive all orders for fly-paper and for preservation of

your hen-pheasant’s life.’ “My friend ascended with the doctor to the chamber of

death, while I remained in the study, turning the whole matter over and over in my head,

and feeling as sombre as ever I had done in my life. What was the past of this Trevor,

pugilist, traveller, and gold-digger, and how had he placed himself in the power of this

acid-faced seaman? Why, too, should he faint at an allusion to the half-effaced initials

upon his arm and die of fright when he had a letter from Fordingham? Then I remembered

that Fordingham was in Hampshire, and that this Mr. Beddoes, whom the seaman had gone to

visit and presumably to blackmail, had also been mentioned as living in Hampshire. The

letter, then, might either come from Hudson, the seaman, saying that he had betrayed the

guilty secret which appeared to exist, or it might come from Beddoes, warning an old

confederate that such a betrayal was imminent. So far it seemed clear enough. But then how

could this letter be trivial and grotesque, as described by the son? He must have misread

it. If so, it must have been one of those ingenious secret codes which mean one thing

while they seem to mean another. I must see this letter. If there was a hidden meaning in

it, I was confident that I could pluck it forth. For an hour I sat pondering over it in

the gloom, until at last a weeping maid brought in a lamp, and close at her heels came my

friend Trevor, pale but composed, with these very papers which lie upon my knee held in

his grasp. He sat down opposite to me, drew the lamp to the edge of the table, and handed

me a short note scribbled, as you see, upon a single sheet of gray paper. ‘The supply

of game for London is going steadily up,’ it ran. ‘Head-keeper Hudson, we

believe, has been now told to receive all orders for fly-paper and for preservation of

your hen-pheasant’s life.’

[380] “I

daresay my face looked as bewildered as yours did just now when first I read this message.

Then I reread it very carefully. It was evidently as I had thought, and some secret

meaning must lie buried in this strange combination of words. Or could it be that there

was a prearranged significance to such phrases as ‘fly-paper’ and

‘hen-pheasant’? Such a meaning would be arbitrary and could not be deduced in

any way. And yet I was loath to believe that this was the case, and the presence of the

word Hudson seemed to show that the subject of the message was as I had guessed, and that

it was from Beddoes rather than the sailor. I tried it backward, but the combination

‘life pheasant’s hen’ was not encouraging. Then I tried alternate words,

but neither ‘the of for’ nor ‘supply game London’ promised to throw

any light upon it. [380] “I

daresay my face looked as bewildered as yours did just now when first I read this message.

Then I reread it very carefully. It was evidently as I had thought, and some secret

meaning must lie buried in this strange combination of words. Or could it be that there

was a prearranged significance to such phrases as ‘fly-paper’ and

‘hen-pheasant’? Such a meaning would be arbitrary and could not be deduced in

any way. And yet I was loath to believe that this was the case, and the presence of the

word Hudson seemed to show that the subject of the message was as I had guessed, and that

it was from Beddoes rather than the sailor. I tried it backward, but the combination

‘life pheasant’s hen’ was not encouraging. Then I tried alternate words,

but neither ‘the of for’ nor ‘supply game London’ promised to throw

any light upon it.

“And then in an instant the key of the riddle was in

my hands, and I saw that every third word, beginning with the first, would give a message

which might well drive old Trevor to despair. “And then in an instant the key of the riddle was in

my hands, and I saw that every third word, beginning with the first, would give a message

which might well drive old Trevor to despair.

“It was short and terse, the warning, as I now read it to

my companion: “It was short and terse, the warning, as I now read it to

my companion:

“ ‘The game is up. Hudson has told all. Fly for your

life.’ “ ‘The game is up. Hudson has told all. Fly for your

life.’

“Victor Trevor sank his face into his shaking hands.

‘It must be that, I suppose,’ said he. ‘This is worse than death, for it

means disgrace as well. But what is the meaning of these “head-keepers” and

“hen-pheasants”?’ “Victor Trevor sank his face into his shaking hands.

‘It must be that, I suppose,’ said he. ‘This is worse than death, for it

means disgrace as well. But what is the meaning of these “head-keepers” and

“hen-pheasants”?’

“ ‘It means nothing to the message, but it might

mean a good deal to us if we had no other means of discovering the sender. You see that he

has begun by writing “The . . . game . . . is,” and so on. Afterwards he had, to

fulfil the prearranged cipher, to fill in any two words in each space. He would naturally

use the first words which came to his mind, and if there were so many which referred to

sport among them, you may be tolerably sure that he is either an ardent shot or interested

in breeding. Do you know anything of this Beddoes?’ “ ‘It means nothing to the message, but it might

mean a good deal to us if we had no other means of discovering the sender. You see that he

has begun by writing “The . . . game . . . is,” and so on. Afterwards he had, to

fulfil the prearranged cipher, to fill in any two words in each space. He would naturally

use the first words which came to his mind, and if there were so many which referred to

sport among them, you may be tolerably sure that he is either an ardent shot or interested

in breeding. Do you know anything of this Beddoes?’

“ ‘Why, now that you mention it,’ said he,

‘I remember that my poor father used to have an invitation from him to shoot over his

preserves every autumn.’ “ ‘Why, now that you mention it,’ said he,

‘I remember that my poor father used to have an invitation from him to shoot over his

preserves every autumn.’

“ ‘Then it is undoubtedly from him that the note

comes,’ said I. ‘It only remains for us to find out what this secret was which

the sailor Hudson seems to have held over the heads of these two wealthy and respected

men.’ “ ‘Then it is undoubtedly from him that the note

comes,’ said I. ‘It only remains for us to find out what this secret was which

the sailor Hudson seems to have held over the heads of these two wealthy and respected

men.’

“ ‘Alas, Holmes, I fear that it is one of sin and

shame!’ cried my friend. ‘But from you I shall have no secrets. Here is the

statement which was drawn up by my father when he knew that the danger from Hudson had

become imminent. I found it in the Japanese cabinet, as he told the doctor. Take it and

read it to me, for I have neither the strength nor the courage to do it myself.’ “ ‘Alas, Holmes, I fear that it is one of sin and

shame!’ cried my friend. ‘But from you I shall have no secrets. Here is the

statement which was drawn up by my father when he knew that the danger from Hudson had

become imminent. I found it in the Japanese cabinet, as he told the doctor. Take it and

read it to me, for I have neither the strength nor the courage to do it myself.’

“These are the very papers, Watson, which he handed to

me, and I will read them to you, as I read them in the old study that night to him. They

are endorsed outside, as you see, ‘Some particulars of the voyage of the bark Gloria

Scott, from her leaving Falmouth on the 8th October, 1855, to her destruction in N.

Lat. 15� 20', W. Long. 25� 14',

on Nov. 6th.’ It is in the form of a letter, and runs in this way. “These are the very papers, Watson, which he handed to

me, and I will read them to you, as I read them in the old study that night to him. They

are endorsed outside, as you see, ‘Some particulars of the voyage of the bark Gloria

Scott, from her leaving Falmouth on the 8th October, 1855, to her destruction in N.

Lat. 15� 20', W. Long. 25� 14',

on Nov. 6th.’ It is in the form of a letter, and runs in this way.

“ ‘My dear, dear son, now that approaching disgrace

begins to darken the closing years of my life, I can write with all truth and honesty that

it is not the terror of the law, it is not the loss of my position in the county, nor is

it my fall in the eyes of all who have known me, which cuts me to the heart; but it is the

thought that you should come to blush for me–you who love me and who have seldom, I

hope, had reason to do other than respect me. But if the blow falls which is forever

hanging over me, then I should wish you to read this, that you may know [381] straight from me how far I

have been to blame. On the other hand, if all should go well (which may kind God Almighty

grant!), then, if by any chance this paper should be still undestroyed and should fall

into your hands, I conjure you, by all you hold sacred, by the memory of your dear mother,

and by the love which has been between us, to hurl it into the fire and to never give one

thought to it again. “ ‘My dear, dear son, now that approaching disgrace

begins to darken the closing years of my life, I can write with all truth and honesty that

it is not the terror of the law, it is not the loss of my position in the county, nor is

it my fall in the eyes of all who have known me, which cuts me to the heart; but it is the

thought that you should come to blush for me–you who love me and who have seldom, I

hope, had reason to do other than respect me. But if the blow falls which is forever

hanging over me, then I should wish you to read this, that you may know [381] straight from me how far I

have been to blame. On the other hand, if all should go well (which may kind God Almighty

grant!), then, if by any chance this paper should be still undestroyed and should fall

into your hands, I conjure you, by all you hold sacred, by the memory of your dear mother,

and by the love which has been between us, to hurl it into the fire and to never give one

thought to it again.

“ ‘If then your eye goes on to read this line, I

know that I shall already have been exposed and dragged from my home, or, as is more

likely, for you know that my heart is weak, be lying with my tongue sealed forever in

death. In either case the time for suppression is past, and every word which I tell you is

the naked truth, and this I swear as I hope for mercy. “ ‘If then your eye goes on to read this line, I

know that I shall already have been exposed and dragged from my home, or, as is more

likely, for you know that my heart is weak, be lying with my tongue sealed forever in

death. In either case the time for suppression is past, and every word which I tell you is

the naked truth, and this I swear as I hope for mercy.

“ ‘My name, dear lad, is not Trevor. I was James

Armitage in my younger days, and you can understand now the shock that it was to me a few

weeks ago when your college friend addressed me in words which seemed to imply that he had

surprised my secret. As Armitage it was that I entered a London banking-house, and as

Armitage I was convicted of breaking my country’s laws, and was sentenced to

transportation. Do not think very harshly of me, laddie. It was a debt of honour, so

called, which I had to pay, and I used money which was not my own to do it, in the

certainty that I could replace it before there could be any possibility of its being

missed. But the most dreadful ill-luck pursued me. The money which I had reckoned upon

never came to hand, and a premature examination of accounts exposed my deficit. The case

might have been dealt leniently with, but the laws were more harshly administered thirty

years ago than now, and on my twenty-third birthday I found myself chained as a felon with

thirty-seven other convicts in the ’tween-decks of the bark Gloria Scott,

bound for Australia. “ ‘My name, dear lad, is not Trevor. I was James

Armitage in my younger days, and you can understand now the shock that it was to me a few

weeks ago when your college friend addressed me in words which seemed to imply that he had

surprised my secret. As Armitage it was that I entered a London banking-house, and as

Armitage I was convicted of breaking my country’s laws, and was sentenced to

transportation. Do not think very harshly of me, laddie. It was a debt of honour, so

called, which I had to pay, and I used money which was not my own to do it, in the

certainty that I could replace it before there could be any possibility of its being

missed. But the most dreadful ill-luck pursued me. The money which I had reckoned upon

never came to hand, and a premature examination of accounts exposed my deficit. The case

might have been dealt leniently with, but the laws were more harshly administered thirty

years ago than now, and on my twenty-third birthday I found myself chained as a felon with

thirty-seven other convicts in the ’tween-decks of the bark Gloria Scott,

bound for Australia.

“ ‘It was the year ’55, when the Crimean War

was at its height, and the old convict ships had been largely used as transports in the

Black Sea. The government was compelled, therefore, to use smaller and less suitable

vessels for sending out their prisoners. The Gloria Scott had been in the Chinese

tea-trade, but she was an old-fashioned, heavy-bowed, broad-beamed craft, and the new

clippers had cut her out. She was a five-hundred-ton boat; and besides her thirty-eight

jail-birds, she carried twenty-six of a crew, eighteen soldiers, a captain, three mates, a

doctor, a chaplain, and four warders. Nearly a hundred souls were in her, all told, when

we set sail from Falmouth. “ ‘It was the year ’55, when the Crimean War

was at its height, and the old convict ships had been largely used as transports in the

Black Sea. The government was compelled, therefore, to use smaller and less suitable

vessels for sending out their prisoners. The Gloria Scott had been in the Chinese

tea-trade, but she was an old-fashioned, heavy-bowed, broad-beamed craft, and the new

clippers had cut her out. She was a five-hundred-ton boat; and besides her thirty-eight

jail-birds, she carried twenty-six of a crew, eighteen soldiers, a captain, three mates, a

doctor, a chaplain, and four warders. Nearly a hundred souls were in her, all told, when

we set sail from Falmouth.

“ ‘The partitions between the cells of the convicts

instead of being of thick oak, as is usual in convict-ships, were quite thin and frail.

The man next to me, upon the aft side, was one whom I had particularly noticed when we

were led down the quay. He was a young man with a clear, hairless face, a long, thin nose,

and rather nut-cracker jaws. He carried his head very jauntily in the air, had a

swaggering style of walking, and was, above all else, remarkable for his extraordinary

height. I don’t think any of our heads would have come up to his shoulder, and I am

sure that he could not have measured less than six and a half feet. It was strange among

so many sad and weary faces to see one which was full of energy and resolution. The sight

of it was to me like a fire in a snowstorm. I was glad, then, to find that he was my

neighbour, and gladder still when, in the dead of the night, I heard a whisper close to my

ear and found that he had managed to cut an opening in the board which separated us. “ ‘The partitions between the cells of the convicts

instead of being of thick oak, as is usual in convict-ships, were quite thin and frail.

The man next to me, upon the aft side, was one whom I had particularly noticed when we

were led down the quay. He was a young man with a clear, hairless face, a long, thin nose,

and rather nut-cracker jaws. He carried his head very jauntily in the air, had a

swaggering style of walking, and was, above all else, remarkable for his extraordinary

height. I don’t think any of our heads would have come up to his shoulder, and I am

sure that he could not have measured less than six and a half feet. It was strange among

so many sad and weary faces to see one which was full of energy and resolution. The sight

of it was to me like a fire in a snowstorm. I was glad, then, to find that he was my

neighbour, and gladder still when, in the dead of the night, I heard a whisper close to my

ear and found that he had managed to cut an opening in the board which separated us.

“ ‘ “Hullo, chummy!” said he,

“what’s your name, and what are you here for?” “ ‘ “Hullo, chummy!” said he,

“what’s your name, and what are you here for?”

“ ‘I answered him, and asked in turn who I was

talking with. “ ‘I answered him, and asked in turn who I was

talking with.

[382] “

‘ “I’m Jack Prendergast,” said he, “and by God! you’ll learn

to bless my name before you’ve done with me.” [382] “

‘ “I’m Jack Prendergast,” said he, “and by God! you’ll learn

to bless my name before you’ve done with me.”

“ ‘I remembered hearing of his case, for it was

one which had made an immense sensation throughout the country some time before my own

arrest. He was a man of good family and of great ability, but of incurably vicious habits,

who had by an ingenious system of fraud obtained huge sums of money from the leading

London merchants. “ ‘I remembered hearing of his case, for it was

one which had made an immense sensation throughout the country some time before my own

arrest. He was a man of good family and of great ability, but of incurably vicious habits,

who had by an ingenious system of fraud obtained huge sums of money from the leading

London merchants.

“ ‘ “Ha, ha! You remember my case!” said

he proudly. “ ‘ “Ha, ha! You remember my case!” said

he proudly.

“ ‘ “Very well, indeed.” “ ‘ “Very well, indeed.”

“ ‘ “Then maybe you remember something queer

about it?” “ ‘ “Then maybe you remember something queer

about it?”

“ ‘ “What was that, then?” “ ‘ “What was that, then?”

“ ‘ “I’d had nearly a quarter of a

million, hadn’t I?” “ ‘ “I’d had nearly a quarter of a

million, hadn’t I?”

“ ‘ “So it was said.” “ ‘ “So it was said.”

“ ‘ “But none was recovered, eh?” “ ‘ “But none was recovered, eh?”

“ ‘ “No.” “ ‘ “No.”

“ ‘ “Well, where d’ye suppose the balance

is?” he asked. “ ‘ “Well, where d’ye suppose the balance

is?” he asked.

“ ‘ “I have no idea,” said I. “ ‘ “I have no idea,” said I.

“ ‘ “Right between my finger and thumb,”

he cried. “By God! I’ve got more pounds to my name than you’ve hairs on

your head. And if you’ve money, my son, and know how to handle it and spread it, you

can do anything. Now, you don’t think it likely that a man who could do

anything is going to wear his breeches out sitting in the stinking hold of a rat-gutted,

beetle-ridden, mouldy old coffin of a Chin China coaster. No, sir, such a man will look

after himself and will look after his chums. You may lay to that! You hold on to him, and

you may kiss the Book that he’ll haul you through.” “ ‘ “Right between my finger and thumb,”

he cried. “By God! I’ve got more pounds to my name than you’ve hairs on

your head. And if you’ve money, my son, and know how to handle it and spread it, you

can do anything. Now, you don’t think it likely that a man who could do

anything is going to wear his breeches out sitting in the stinking hold of a rat-gutted,

beetle-ridden, mouldy old coffin of a Chin China coaster. No, sir, such a man will look

after himself and will look after his chums. You may lay to that! You hold on to him, and

you may kiss the Book that he’ll haul you through.”

“ ‘That was his style of talk, and at first I

thought it meant nothing; but after a while, when he had tested me and sworn me in with

all possible solemnity, he let me understand that there really was a plot to gain command

of the vessel. A dozen of the prisoners had hatched it before they came aboard,

Prendergast was the leader, and his money was the motive power. “ ‘That was his style of talk, and at first I

thought it meant nothing; but after a while, when he had tested me and sworn me in with

all possible solemnity, he let me understand that there really was a plot to gain command

of the vessel. A dozen of the prisoners had hatched it before they came aboard,

Prendergast was the leader, and his money was the motive power.

“ ‘ “I’d a partner,” said he, “a

rare good man, as true as a stock to a barrel. He’s got the dibbs, he has, and where

do you think he is at this moment? Why, he’s the chaplain of this ship–the

chaplain, no less! He came aboard with a black coat, and his papers right, and money

enough in his box to buy the thing right up from keel to main-truck. The crew are his,

body and soul. He could buy ’em at so much a gross with a cash discount, and he did

it before ever they signed on. He’s got two of the warders and Mereer, the second

mate, and he’d get the captain himself, if he thought him worth it.” “ ‘ “I’d a partner,” said he, “a

rare good man, as true as a stock to a barrel. He’s got the dibbs, he has, and where

do you think he is at this moment? Why, he’s the chaplain of this ship–the

chaplain, no less! He came aboard with a black coat, and his papers right, and money

enough in his box to buy the thing right up from keel to main-truck. The crew are his,

body and soul. He could buy ’em at so much a gross with a cash discount, and he did

it before ever they signed on. He’s got two of the warders and Mereer, the second

mate, and he’d get the captain himself, if he thought him worth it.”

“ ‘ “What are we to do, then?” I asked. “ ‘ “What are we to do, then?” I asked.

“ ‘ “What do you think?” said he.

“We’ll make the coats of some of these soldiers redder than ever the tailor

did.” “ ‘ “What do you think?” said he.

“We’ll make the coats of some of these soldiers redder than ever the tailor

did.”

“ ‘ “But they are armed,” said I. “ ‘ “But they are armed,” said I.

“ ‘ “And so shall we be, my boy. There’s a

brace of pistols for every mother’s son of us; and if we can’t carry this ship,

with the crew at our back, it’s time we were all sent to a young misses’

boarding-school. You speak to your mate upon the left to-night, and see if he is to be

trusted.” “ ‘ “And so shall we be, my boy. There’s a

brace of pistols for every mother’s son of us; and if we can’t carry this ship,

with the crew at our back, it’s time we were all sent to a young misses’

boarding-school. You speak to your mate upon the left to-night, and see if he is to be

trusted.”

“ ‘I did so and found my other neighbour to be a

young fellow in much the same position as myself, whose crime had been forgery. His name

was Evans, but he afterwards changed it, like myself, and he is now a rich and prosperous

man in the [383] south of

England. He was ready enough to join the conspiracy, as the only means of saving

ourselves, and before we had crossed the bay there were only two of the prisoners who were

not in the secret. One of these was of weak mind, and we did not dare to trust him, and

the other was suffering from jaundice and could not be of any use to us. “ ‘I did so and found my other neighbour to be a

young fellow in much the same position as myself, whose crime had been forgery. His name

was Evans, but he afterwards changed it, like myself, and he is now a rich and prosperous

man in the [383] south of

England. He was ready enough to join the conspiracy, as the only means of saving

ourselves, and before we had crossed the bay there were only two of the prisoners who were

not in the secret. One of these was of weak mind, and we did not dare to trust him, and

the other was suffering from jaundice and could not be of any use to us.

“ ‘From the beginning there was really nothing to

prevent us from taking possession of the ship. The crew were a set of ruffians, specially

picked for the job. The sham chaplain came into our cells to exhort us, carrying a black

bag, supposed to be full of tracts, and so often did he come that by the third day we had

each stowed away at the foot of our beds a file, a brace of pistols, a pound of powder,

and twenty slugs. Two of the warders were agents of Prendergast, and the second mate was

his right-hand man. The captain, the two mates, two warders, Lieutenant Martin, his

eighteen soldiers, and the doctor were all that we had against us. Yet, safe as it was, we

determined to neglect no precaution, and to make our attack suddenly by night. It came,

however, more quickly than we expected, and in this way. “ ‘From the beginning there was really nothing to

prevent us from taking possession of the ship. The crew were a set of ruffians, specially

picked for the job. The sham chaplain came into our cells to exhort us, carrying a black

bag, supposed to be full of tracts, and so often did he come that by the third day we had

each stowed away at the foot of our beds a file, a brace of pistols, a pound of powder,

and twenty slugs. Two of the warders were agents of Prendergast, and the second mate was

his right-hand man. The captain, the two mates, two warders, Lieutenant Martin, his

eighteen soldiers, and the doctor were all that we had against us. Yet, safe as it was, we

determined to neglect no precaution, and to make our attack suddenly by night. It came,

however, more quickly than we expected, and in this way.

“ ‘One evening, about the third week after our

start, the doctor had come down to see one of the prisoners who was ill, and, putting his

hand down on the bottom of his bunk, he felt the outline of the pistols. If he had been

silent he might have blown the whole thing, but he was a nervous little chap, so he gave a

cry of surprise and turned so pale that the man knew what was up in an instant and seized

him. He was gagged before he could give the alarm and tied down upon the bed. He had

unlocked the door that led to the deck, and we were through it in a rush. The two sentries

were shot down, and so was a corporal who came running to see what was the matter. There

were two more soldiers at the door of the stateroom, and their muskets seemed not to be

loaded, for they never fired upon us, and they were shot while trying to fix their

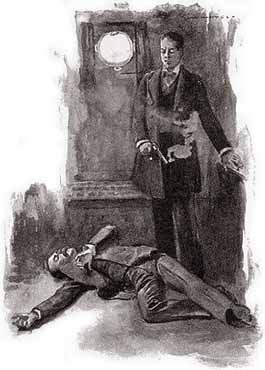

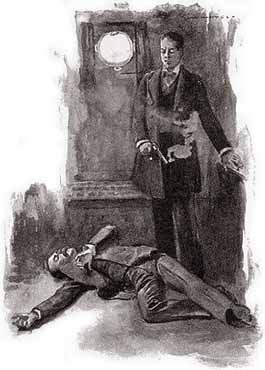

bayonets. Then we rushed on into the captain’s cabin, but as we pushed open the door

there was an explosion from within, and there he lay with his brains smeared over the

chart of the Atlantic which was pinned upon the table, while the chaplain stood with a

smoking pistol in his hand at his elbow. The two mates had both been seized by the crew,

and the whole business seemed to be settled. “ ‘One evening, about the third week after our

start, the doctor had come down to see one of the prisoners who was ill, and, putting his

hand down on the bottom of his bunk, he felt the outline of the pistols. If he had been

silent he might have blown the whole thing, but he was a nervous little chap, so he gave a

cry of surprise and turned so pale that the man knew what was up in an instant and seized

him. He was gagged before he could give the alarm and tied down upon the bed. He had

unlocked the door that led to the deck, and we were through it in a rush. The two sentries

were shot down, and so was a corporal who came running to see what was the matter. There

were two more soldiers at the door of the stateroom, and their muskets seemed not to be

loaded, for they never fired upon us, and they were shot while trying to fix their

bayonets. Then we rushed on into the captain’s cabin, but as we pushed open the door

there was an explosion from within, and there he lay with his brains smeared over the

chart of the Atlantic which was pinned upon the table, while the chaplain stood with a

smoking pistol in his hand at his elbow. The two mates had both been seized by the crew,

and the whole business seemed to be settled.

“ ‘The stateroom was next the cabin, and we

flocked in there and flopped down on the settees, all speaking together, for we were just

mad with the feeling that we were free once more. There were lockers all round, and

Wilson, the sham chaplain, knocked one of them in, and pulled out a dozen of brown sherry.

We cracked off the necks of the bottles, poured the stuff out into tumblers, and were just

tossing them off when in an instant without warning there came the roar of muskets in our

ears, and the saloon was so full of smoke that we could not see across the table. When it

cleared again the place was a shambles. Wilson and eight others were wriggling on the top

of each other on the floor, and the blood and the brown sherry on that table turn me sick

now when I think of it. We were so cowed by the sight that I think we should have given

the job up if it had not been for Prendergast. He bellowed like a bull and rushed for the

door with all that were left alive at his heels. Out we ran, and there on the poop were

the lieutenant and ten of his men. The swing skylights above the saloon table had been a

bit open, and they had fired on us through the slit. We got on them before they could

load, and they stood to it like men; but we had the upper hand of them, and in five

minutes it was all over. My God! was there ever a slaughter-house like [384] that ship! Prendergast was

like a raging devil, and he picked the soldiers up as if they had been children and threw

them overboard alive or dead. There was one sergeant that was horribly wounded and yet

kept on swimming for a surprising time until someone in mercy blew out his brains. When

the fighting was over there was no one left of our enemies except just the warders, the

mates, and the doctor. “ ‘The stateroom was next the cabin, and we

flocked in there and flopped down on the settees, all speaking together, for we were just

mad with the feeling that we were free once more. There were lockers all round, and

Wilson, the sham chaplain, knocked one of them in, and pulled out a dozen of brown sherry.

We cracked off the necks of the bottles, poured the stuff out into tumblers, and were just

tossing them off when in an instant without warning there came the roar of muskets in our

ears, and the saloon was so full of smoke that we could not see across the table. When it

cleared again the place was a shambles. Wilson and eight others were wriggling on the top

of each other on the floor, and the blood and the brown sherry on that table turn me sick

now when I think of it. We were so cowed by the sight that I think we should have given

the job up if it had not been for Prendergast. He bellowed like a bull and rushed for the

door with all that were left alive at his heels. Out we ran, and there on the poop were

the lieutenant and ten of his men. The swing skylights above the saloon table had been a

bit open, and they had fired on us through the slit. We got on them before they could

load, and they stood to it like men; but we had the upper hand of them, and in five

minutes it was all over. My God! was there ever a slaughter-house like [384] that ship! Prendergast was

like a raging devil, and he picked the soldiers up as if they had been children and threw

them overboard alive or dead. There was one sergeant that was horribly wounded and yet

kept on swimming for a surprising time until someone in mercy blew out his brains. When

the fighting was over there was no one left of our enemies except just the warders, the

mates, and the doctor.

“ ‘It was over them that the great quarrel arose.

There were many of us who were glad enough to win back our freedom, and yet who had no

wish to have murder on our souls. It was one thing to knock the soldiers over with their

muskets in their hands, and it was another to stand by while men were being killed in cold

blood. Eight of us, five convicts and three sailors, said that we would not see it done.

But there was no moving Prendergast and those who were with him. Our only chance of safety

lay in making a clean job of it, said he, and he would not leave a tongue with power to

wag in a witness-box. It nearly came to our sharing the fate of the prisoners, but at last

he said that if we wished we might take a boat and go. We jumped at the offer, for we were

already sick of these bloodthirsty doings, and we saw that there would be worse before it

was done. We were given a suit of sailor togs each, a barrel of water, two casks, one of

junk and one of biscuits, and a compass. Prendergast threw us over a chart, told us that

we were shipwrecked mariners whose ship had foundered in Lat. 15� and

Long. 25� west, and then cut the painter and let us go. “ ‘It was over them that the great quarrel arose.

There were many of us who were glad enough to win back our freedom, and yet who had no

wish to have murder on our souls. It was one thing to knock the soldiers over with their

muskets in their hands, and it was another to stand by while men were being killed in cold

blood. Eight of us, five convicts and three sailors, said that we would not see it done.

But there was no moving Prendergast and those who were with him. Our only chance of safety

lay in making a clean job of it, said he, and he would not leave a tongue with power to

wag in a witness-box. It nearly came to our sharing the fate of the prisoners, but at last

he said that if we wished we might take a boat and go. We jumped at the offer, for we were

already sick of these bloodthirsty doings, and we saw that there would be worse before it

was done. We were given a suit of sailor togs each, a barrel of water, two casks, one of

junk and one of biscuits, and a compass. Prendergast threw us over a chart, told us that

we were shipwrecked mariners whose ship had foundered in Lat. 15� and

Long. 25� west, and then cut the painter and let us go.

“ ‘And now I come to the most surprising part of my

story, my dear son. The seamen had hauled the fore-yard aback during the rising, but now

as we left them they brought it square again, and as there was a light wind from the north

and east the bark began to draw slowly away from us. Our boat lay, rising and falling,

upon the long, smooth rollers, and Evans and I, who were the most educated of the party,

were sitting in the sheets working out our position and planning what coast we should make

for. It was a nice question, for the Cape Verdes were about five hundred miles to the

north of us, and the African coast about seven hundred to the east. On the whole, as the

wind was coming round to the north, we thought that Sierra Leone might be best and turned

our head in that direction, the bark being at that time nearly hull down on our starboard

quarter. Suddenly as we looked at her we saw a dense black cloud of smoke shoot up from

her, which hung like a monstrous tree upon the sky-line. A few seconds later a roar like

thunder burst upon our ears, and as the smoke thinned away there was no sign left of the Gloria

Scott. In an instant we swept the boat’s head round again and pulled with all

our strength for the place where the haze still trailing over the water marked the scene

of this catastrophe. “ ‘And now I come to the most surprising part of my

story, my dear son. The seamen had hauled the fore-yard aback during the rising, but now

as we left them they brought it square again, and as there was a light wind from the north

and east the bark began to draw slowly away from us. Our boat lay, rising and falling,

upon the long, smooth rollers, and Evans and I, who were the most educated of the party,

were sitting in the sheets working out our position and planning what coast we should make

for. It was a nice question, for the Cape Verdes were about five hundred miles to the

north of us, and the African coast about seven hundred to the east. On the whole, as the

wind was coming round to the north, we thought that Sierra Leone might be best and turned

our head in that direction, the bark being at that time nearly hull down on our starboard

quarter. Suddenly as we looked at her we saw a dense black cloud of smoke shoot up from

her, which hung like a monstrous tree upon the sky-line. A few seconds later a roar like

thunder burst upon our ears, and as the smoke thinned away there was no sign left of the Gloria

Scott. In an instant we swept the boat’s head round again and pulled with all

our strength for the place where the haze still trailing over the water marked the scene

of this catastrophe.

“ ‘It was a long hour before we reached it, and at

first we feared that we had come too late to save anyone. A splintered boat and a number

of crates and fragments of spars rising and falling on the waves showed us where the

vessel had foundered; but there was no sign of life, and we had turned away in despair,

when we heard a cry for help and saw at some distance a piece of wreckage with a man lying

stretched across it. When we pulled him aboard the boat he proved to be a young seaman of

the name of Hudson, who was so burned and exhausted that he could give us no account of

what had happened until the following morning. “ ‘It was a long hour before we reached it, and at

first we feared that we had come too late to save anyone. A splintered boat and a number

of crates and fragments of spars rising and falling on the waves showed us where the

vessel had foundered; but there was no sign of life, and we had turned away in despair,

when we heard a cry for help and saw at some distance a piece of wreckage with a man lying

stretched across it. When we pulled him aboard the boat he proved to be a young seaman of

the name of Hudson, who was so burned and exhausted that he could give us no account of

what had happened until the following morning.

“ ‘It seemed that after we had left, Prendergast

and his gang had proceeded to put to death the five remaining prisoners. The two warders

had been shot and thrown overboard, and so also had the third mate. Prendergast then

descended into [385] the

’tween-decks and with his own hands cut the throat of the unfortunate surgeon. There

only remained the first mate, who was a bold and active man. When he saw the convict

approaching him with the bloody knife in his hand he kicked off his bonds, which he had

somehow contrived to loosen, and rushing down the deck he plunged into the after-hold. A

dozen convicts, who descended with their pistols in search of him, found him with a

match-box in his hand seated beside an open powder-barrel, which was one of the hundred

carried on board, and swearing that he would blow all hands up if he were in any way

molested. An instant later the explosion occurred, though Hudson thought it was caused by

the misdirected bullet of one of the convicts rather than the mate’s match. Be the

cause what it may, it was the end of the Gloria Scott and of the rabble who held

command of her. “ ‘It seemed that after we had left, Prendergast

and his gang had proceeded to put to death the five remaining prisoners. The two warders

had been shot and thrown overboard, and so also had the third mate. Prendergast then

descended into [385] the

’tween-decks and with his own hands cut the throat of the unfortunate surgeon. There

only remained the first mate, who was a bold and active man. When he saw the convict

approaching him with the bloody knife in his hand he kicked off his bonds, which he had

somehow contrived to loosen, and rushing down the deck he plunged into the after-hold. A

dozen convicts, who descended with their pistols in search of him, found him with a

match-box in his hand seated beside an open powder-barrel, which was one of the hundred

carried on board, and swearing that he would blow all hands up if he were in any way

molested. An instant later the explosion occurred, though Hudson thought it was caused by

the misdirected bullet of one of the convicts rather than the mate’s match. Be the

cause what it may, it was the end of the Gloria Scott and of the rabble who held

command of her.

“ ‘Such, in a few words, my dear boy, is the history

of this terrible business in which I was involved. Next day we were picked up by the brig Hotspur,

bound for Australia, whose captain found no difficulty in believing that we were the

survivors of a passenger ship which had foundered. The transport ship Gloria Scott

was set down by the Admiralty as being lost at sea, and no word has ever leaked out as to

her true fate. After an excellent voyage the Hotspur landed us at Sydney, where

Evans and I changed our names and made our way to the diggings, where, among the crowds

who were gathered from all nations, we had no difficulty in losing our former identities.

The rest I need not relate. We prospered, we travelled, we came back as rich colonials to

England, and we bought country estates. For more than twenty years we have led peaceful

and useful lives, and we hoped that our past was forever buried. Imagine, then, my

feelings when in the seaman who came to us I recognized instantly the man who had been

picked off the wreck. He had tracked us down somehow and had set himself to live upon our

fears. You will understand now how it was that I strove to keep the peace with him, and

you will in some measure sympathize with me in the fears which fill me, now that he has

gone from me to his other victim with threats upon his tongue.’ “ ‘Such, in a few words, my dear boy, is the history

of this terrible business in which I was involved. Next day we were picked up by the brig Hotspur,

bound for Australia, whose captain found no difficulty in believing that we were the

survivors of a passenger ship which had foundered. The transport ship Gloria Scott

was set down by the Admiralty as being lost at sea, and no word has ever leaked out as to

her true fate. After an excellent voyage the Hotspur landed us at Sydney, where

Evans and I changed our names and made our way to the diggings, where, among the crowds

who were gathered from all nations, we had no difficulty in losing our former identities.

The rest I need not relate. We prospered, we travelled, we came back as rich colonials to

England, and we bought country estates. For more than twenty years we have led peaceful

and useful lives, and we hoped that our past was forever buried. Imagine, then, my

feelings when in the seaman who came to us I recognized instantly the man who had been

picked off the wreck. He had tracked us down somehow and had set himself to live upon our

fears. You will understand now how it was that I strove to keep the peace with him, and

you will in some measure sympathize with me in the fears which fill me, now that he has

gone from me to his other victim with threats upon his tongue.’

“Underneath is written in a hand so shaky as to be

hardly legible, ‘Beddoes writes in cipher to say H. has told all. Sweet Lord, have

mercy on our souls!’ “Underneath is written in a hand so shaky as to be

hardly legible, ‘Beddoes writes in cipher to say H. has told all. Sweet Lord, have

mercy on our souls!’

“That was the narrative which I read that night to young

Trevor, and I think, Watson, that under the circumstances it was a dramatic one. The good

fellow was heart-broken at it, and went out to the Terai tea planting, where I hear that

he is doing well. As to the sailor and Beddoes, neither of them was ever heard of again

after that day on which the letter of warning was written. They both disappeared utterly

and completely. No complaint had been lodged with the police, so that Beddoes had mistaken

a threat for a deed. Hudson had been seen lurking about, and it was believed by the police

that he had done away with Beddoes and had fled. For myself I believe that the truth was

exactly the opposite. I think that it is most probable that Beddoes, pushed to desperation

and believing himself to have been already betrayed, had revenged himself upon Hudson, and

had fled from the country with as much money as he could lay his hands on. Those are the

facts of the case, Doctor, and if they are of any use to your collection, I am sure that

they are very heartily at your service.” “That was the narrative which I read that night to young

Trevor, and I think, Watson, that under the circumstances it was a dramatic one. The good

fellow was heart-broken at it, and went out to the Terai tea planting, where I hear that

he is doing well. As to the sailor and Beddoes, neither of them was ever heard of again

after that day on which the letter of warning was written. They both disappeared utterly

and completely. No complaint had been lodged with the police, so that Beddoes had mistaken

a threat for a deed. Hudson had been seen lurking about, and it was believed by the police

that he had done away with Beddoes and had fled. For myself I believe that the truth was

exactly the opposite. I think that it is most probable that Beddoes, pushed to desperation

and believing himself to have been already betrayed, had revenged himself upon Hudson, and