|

|

As you value your life or your reason keep away from the

moor. As you value your life or your reason keep away from the

moor.

The word “moor” only was printed in ink. The word “moor” only was printed in ink.

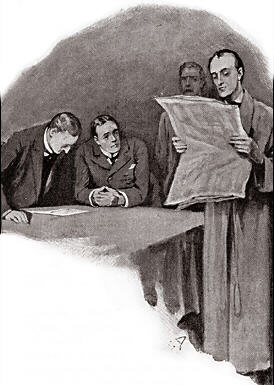

“Now,” said Sir Henry Baskerville, “perhaps you

will tell me, Mr. Holmes, what in thunder is the meaning of that, and who it is that takes

so much interest in my affairs?” “Now,” said Sir Henry Baskerville, “perhaps you

will tell me, Mr. Holmes, what in thunder is the meaning of that, and who it is that takes

so much interest in my affairs?”

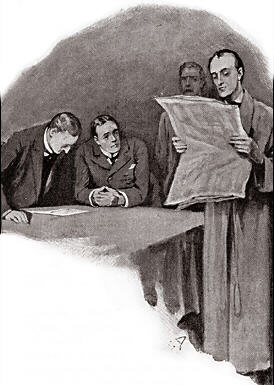

[686]

“What do you make of it, Dr. Mortimer? You must allow that there is nothing

supernatural about this, at any rate?” [686]

“What do you make of it, Dr. Mortimer? You must allow that there is nothing

supernatural about this, at any rate?”

“No, sir, but it might very well come from someone who

was convinced that the business is supernatural.” “No, sir, but it might very well come from someone who

was convinced that the business is supernatural.”

“What business?” asked Sir Henry sharply. “It

seems to me that all you gentlemen know a great deal more than I do about my own

affairs.” “What business?” asked Sir Henry sharply. “It

seems to me that all you gentlemen know a great deal more than I do about my own

affairs.”

“You shall share our knowledge before you leave this

room, Sir Henry. I promise you that,” said Sherlock Holmes. “We will confine

ourselves for the present with your permission to this very interesting document, which

must have been put together and posted yesterday evening. Have you yesterday’s Times,

Watson?” “You shall share our knowledge before you leave this

room, Sir Henry. I promise you that,” said Sherlock Holmes. “We will confine

ourselves for the present with your permission to this very interesting document, which

must have been put together and posted yesterday evening. Have you yesterday’s Times,

Watson?”

“It is here in the corner.” “It is here in the corner.”

“Might I trouble you for it–the inside page, please,

with the leading articles?” He glanced swiftly over it, running his eyes up and down

the columns. “Capital article this on free trade. Permit me to give you an extract

from it. “Might I trouble you for it–the inside page, please,

with the leading articles?” He glanced swiftly over it, running his eyes up and down

the columns. “Capital article this on free trade. Permit me to give you an extract

from it.

“You may be cajoled into imagining that your own

special trade or your own industry will be encouraged by a protective tariff, but it

stands to reason that such legislation must in the long run keep away wealth from the

country, diminish the value of our imports, and lower the general conditions of life in

this island. “You may be cajoled into imagining that your own

special trade or your own industry will be encouraged by a protective tariff, but it

stands to reason that such legislation must in the long run keep away wealth from the

country, diminish the value of our imports, and lower the general conditions of life in

this island.

What do you think of that, Watson?” cried Holmes in

high glee, rubbing his hands together with satisfaction. “Don’t you think that

is an admirable sentiment?” What do you think of that, Watson?” cried Holmes in

high glee, rubbing his hands together with satisfaction. “Don’t you think that

is an admirable sentiment?”

Dr. Mortimer looked at Holmes with an air of professional

interest, and Sir Henry Baskerville turned a pair of puzzled dark eyes upon me. Dr. Mortimer looked at Holmes with an air of professional

interest, and Sir Henry Baskerville turned a pair of puzzled dark eyes upon me.

“I don’t know much about the tariff and things of

that kind,” said he, “but it seems to me we’ve got a bit off the trail so

far as that note is concerned.” “I don’t know much about the tariff and things of

that kind,” said he, “but it seems to me we’ve got a bit off the trail so

far as that note is concerned.”

“On the contrary, I think we are particularly hot upon

the trail, Sir Henry. Watson here knows more about my methods than you do, but I fear that

even he has not quite grasped the significance of this sentence.” “On the contrary, I think we are particularly hot upon

the trail, Sir Henry. Watson here knows more about my methods than you do, but I fear that

even he has not quite grasped the significance of this sentence.”

“No, I confess that I see no connection.” “No, I confess that I see no connection.”

“And yet, my dear Watson, there is so very close a

connection that the one is extracted out of the other. ‘You,’ ‘your,’

‘your,’ ‘life,’ ‘reason,’ ‘value,’ ‘keep

away,’ ‘from the.’ Don’t you see now whence these words have been

taken?” “And yet, my dear Watson, there is so very close a

connection that the one is extracted out of the other. ‘You,’ ‘your,’

‘your,’ ‘life,’ ‘reason,’ ‘value,’ ‘keep

away,’ ‘from the.’ Don’t you see now whence these words have been

taken?”

“By thunder, you’re right! Well, if that isn’t

smart!” cried Sir Henry. “By thunder, you’re right! Well, if that isn’t

smart!” cried Sir Henry.

“If any possible doubt remained it is settled by the fact

that ‘keep away’ and ‘from the’ are cut out in one piece.” “If any possible doubt remained it is settled by the fact

that ‘keep away’ and ‘from the’ are cut out in one piece.”

“Well, now–so it is!” “Well, now–so it is!”

“Really, Mr. Holmes, this exceeds anything which I could

have imagined,” said Dr. Mortimer, gazing at my friend in amazement. “I could

understand anyone saying that the words were from a newspaper; but that you should name

which, and add that it came from the leading article, is really one of the most remarkable

things which I have ever known. How did you do it?” “Really, Mr. Holmes, this exceeds anything which I could

have imagined,” said Dr. Mortimer, gazing at my friend in amazement. “I could

understand anyone saying that the words were from a newspaper; but that you should name

which, and add that it came from the leading article, is really one of the most remarkable

things which I have ever known. How did you do it?”

“I presume, Doctor, that you could tell the skull of a

negro from that of an Esquimau?” “I presume, Doctor, that you could tell the skull of a

negro from that of an Esquimau?”

“Most certainly.” “Most certainly.”

“But how?” “But how?”

“Because that is my special hobby. The differences are

obvious. The supra-orbital crest, the facial angle, the maxillary curve, the–

–” “Because that is my special hobby. The differences are

obvious. The supra-orbital crest, the facial angle, the maxillary curve, the–

–”

“But this is my special hobby, and the differences are

equally obvious. There is [687]

as much difference to my eyes between the leaded bourgeois type of a Times article

and the slovenly print of an evening half-penny paper as there could be between your negro

and your Esquimau. The detection of types is one of the most elementary branches of

knowledge to the special expert in crime, though I confess that once when I was very young

I confused the Leeds Mercury with the Western Morning News. But a Times

leader is entirely distinctive, and these words could have been taken from nothing

else. As it was done yesterday the strong probability was that we should find the words in

yesterday’s issue.” “But this is my special hobby, and the differences are

equally obvious. There is [687]

as much difference to my eyes between the leaded bourgeois type of a Times article

and the slovenly print of an evening half-penny paper as there could be between your negro

and your Esquimau. The detection of types is one of the most elementary branches of

knowledge to the special expert in crime, though I confess that once when I was very young

I confused the Leeds Mercury with the Western Morning News. But a Times

leader is entirely distinctive, and these words could have been taken from nothing

else. As it was done yesterday the strong probability was that we should find the words in

yesterday’s issue.”

“So far as I can follow you, then, Mr. Holmes,” said

Sir Henry Baskerville, “someone cut out this message with a scissors–

–” “So far as I can follow you, then, Mr. Holmes,” said

Sir Henry Baskerville, “someone cut out this message with a scissors–

–”

“Nail-scissors,” said Holmes. “You can see that

it was a very short-bladed scissors, since the cutter had to take two snips over

‘keep away.’” “Nail-scissors,” said Holmes. “You can see that

it was a very short-bladed scissors, since the cutter had to take two snips over

‘keep away.’”

“That is so. Someone, then, cut out the message with a

pair of short-bladed scissors, pasted it with paste– –” “That is so. Someone, then, cut out the message with a

pair of short-bladed scissors, pasted it with paste– –”

“Gum,” said Holmes. “Gum,” said Holmes.

“With gum on to the paper. But I want to know why the

word ‘moor’ should have been written?” “With gum on to the paper. But I want to know why the

word ‘moor’ should have been written?”

“Because he could not find it in print. The other words

were all simple and might be found in any issue, but ‘moor’ would be less

common.” “Because he could not find it in print. The other words

were all simple and might be found in any issue, but ‘moor’ would be less

common.”

“Why, of course, that would explain it. Have you read

anything else in this message, Mr. Holmes?” “Why, of course, that would explain it. Have you read

anything else in this message, Mr. Holmes?”

“There are one or two indications, and yet the utmost

pains have been taken to remove all clues. The address, you observe, is printed in rough

characters. But the Times is a paper which is seldom found in any hands but those

of the highly educated. We may take it, therefore, that the letter was composed by an

educated man who wished to pose as an uneducated one, and his effort to conceal his own

writing suggests that that writing might be known, or come to be known, by you. Again, you

will observe that the words are not gummed on in an accurate line, but that some are much

higher than others. ‘Life,’ for example, is quite out of its proper place. That

may point to carelessness or it may point to agitation and hurry upon the part of the

cutter. On the whole I incline to the latter view, since the matter was evidently

important, and it is unlikely that the composer of such a letter would be careless. If he

were in a hurry it opens up the interesting question why he should be in a hurry, since

any letter posted up to early morning would reach Sir Henry before he would leave his

hotel. Did the composer fear an interruption–and from whom?” “There are one or two indications, and yet the utmost

pains have been taken to remove all clues. The address, you observe, is printed in rough

characters. But the Times is a paper which is seldom found in any hands but those

of the highly educated. We may take it, therefore, that the letter was composed by an

educated man who wished to pose as an uneducated one, and his effort to conceal his own

writing suggests that that writing might be known, or come to be known, by you. Again, you

will observe that the words are not gummed on in an accurate line, but that some are much

higher than others. ‘Life,’ for example, is quite out of its proper place. That

may point to carelessness or it may point to agitation and hurry upon the part of the

cutter. On the whole I incline to the latter view, since the matter was evidently

important, and it is unlikely that the composer of such a letter would be careless. If he

were in a hurry it opens up the interesting question why he should be in a hurry, since

any letter posted up to early morning would reach Sir Henry before he would leave his

hotel. Did the composer fear an interruption–and from whom?”

“We are coming now rather into the region of

guesswork,” said Dr. Mortimer. “We are coming now rather into the region of

guesswork,” said Dr. Mortimer.

“Say, rather, into the region where we balance

probabilities and choose the most likely. It is the scientific use of the imagination, but

we have always some material basis on which to start our speculation. Now, you would call

it a guess, no doubt, but I am almost certain that this address has been written in a

hotel.” “Say, rather, into the region where we balance

probabilities and choose the most likely. It is the scientific use of the imagination, but

we have always some material basis on which to start our speculation. Now, you would call

it a guess, no doubt, but I am almost certain that this address has been written in a

hotel.”

“How in the world can you say that?” “How in the world can you say that?”

“If you examine it carefully you will see that both the

pen and the ink have given the writer trouble. The pen has spluttered twice in a single

word and has run dry three times in a short address, showing that there was very little

ink in the bottle. Now, a private pen or ink-bottle is seldom allowed to be in such a

state, and the combination of the two must be quite rare. But you know the hotel ink and

the hotel pen, where it is rare to get anything else. Yes, I have very little hesitation

in saying that could we examine the waste-paper baskets of the hotels [688] around Charing Cross until we found

the remains of the mutilated Times leader we could lay our hands straight upon

the person who sent this singular message. Halloa! Halloa! What’s this?” “If you examine it carefully you will see that both the

pen and the ink have given the writer trouble. The pen has spluttered twice in a single

word and has run dry three times in a short address, showing that there was very little

ink in the bottle. Now, a private pen or ink-bottle is seldom allowed to be in such a

state, and the combination of the two must be quite rare. But you know the hotel ink and

the hotel pen, where it is rare to get anything else. Yes, I have very little hesitation

in saying that could we examine the waste-paper baskets of the hotels [688] around Charing Cross until we found

the remains of the mutilated Times leader we could lay our hands straight upon

the person who sent this singular message. Halloa! Halloa! What’s this?”

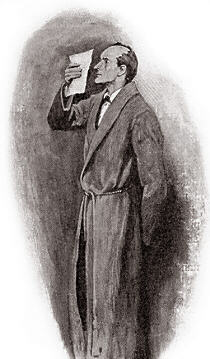

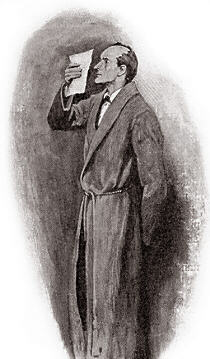

He was carefully examining the foolscap, upon which the words

were pasted, holding it only an inch or two from his eyes. He was carefully examining the foolscap, upon which the words

were pasted, holding it only an inch or two from his eyes.

“Well?” “Well?”

“Nothing,” said he, throwing it down. “It is a

blank half-sheet of paper, without even a water-mark upon it. I think we have drawn as

much as we can from this curious letter; and now, Sir Henry, has anything else of interest

happened to you since you have been in London?” “Nothing,” said he, throwing it down. “It is a

blank half-sheet of paper, without even a water-mark upon it. I think we have drawn as

much as we can from this curious letter; and now, Sir Henry, has anything else of interest

happened to you since you have been in London?”

“Why, no, Mr. Holmes. I think not.” “Why, no, Mr. Holmes. I think not.”

“You have not observed anyone follow or watch you?” “You have not observed anyone follow or watch you?”

“I seem to have walked right into the thick of a dime

novel,” said our visitor. “Why in thunder should anyone follow or watch

me?” “I seem to have walked right into the thick of a dime

novel,” said our visitor. “Why in thunder should anyone follow or watch

me?”

“We are coming to that. You have nothing else to report

to us before we go into this matter?” “We are coming to that. You have nothing else to report

to us before we go into this matter?”

“Well, it depends upon what you think worth

reporting.” “Well, it depends upon what you think worth

reporting.”

“I think anything out of the ordinary routine of life

well worth reporting.” “I think anything out of the ordinary routine of life

well worth reporting.”

Sir Henry smiled. Sir Henry smiled.

“I don’t know much of British life yet, for I have

spent nearly all my time in the States and in Canada. But I hope that to lose one of your

boots is not part of the ordinary routine of life over here.” “I don’t know much of British life yet, for I have

spent nearly all my time in the States and in Canada. But I hope that to lose one of your

boots is not part of the ordinary routine of life over here.”

“You have lost one of your boots?” “You have lost one of your boots?”

“My dear sir,” cried Dr. Mortimer, “it is only

mislaid. You will find it when you return to the hotel. What is the use of troubling Mr.

Holmes with trifles of this kind?” “My dear sir,” cried Dr. Mortimer, “it is only

mislaid. You will find it when you return to the hotel. What is the use of troubling Mr.

Holmes with trifles of this kind?”

“Well, he asked me for anything outside the ordinary

routine.” “Well, he asked me for anything outside the ordinary

routine.”

“Exactly,” said Holmes, “however foolish the

incident may seem. You have lost one of your boots, you say?” “Exactly,” said Holmes, “however foolish the

incident may seem. You have lost one of your boots, you say?”

“Well, mislaid it, anyhow. I put them both outside my

door last night, and there was only one in the morning. I could get no sense out of the

chap who cleans them. The worst of it is that I only bought the pair last night in the

Strand, and I have never had them on.” “Well, mislaid it, anyhow. I put them both outside my

door last night, and there was only one in the morning. I could get no sense out of the

chap who cleans them. The worst of it is that I only bought the pair last night in the

Strand, and I have never had them on.”

“If you have never worn them, why did you put them out to

be cleaned?” “If you have never worn them, why did you put them out to

be cleaned?”

“They were tan boots and had never been varnished. That

was why I put them out.” “They were tan boots and had never been varnished. That

was why I put them out.”

“Then I understand that on your arrival in London

yesterday you went out at once and bought a pair of boots?” “Then I understand that on your arrival in London

yesterday you went out at once and bought a pair of boots?”

“I did a good deal of shopping. Dr. Mortimer here went

round with me. You see, if I am to be squire down there I must dress the part, and it may

be that I have got a little careless in my ways out West. Among other things I bought

these brown boots–gave six dollars for them–and had one stolen before ever I had

them on my feet.” “I did a good deal of shopping. Dr. Mortimer here went

round with me. You see, if I am to be squire down there I must dress the part, and it may

be that I have got a little careless in my ways out West. Among other things I bought

these brown boots–gave six dollars for them–and had one stolen before ever I had

them on my feet.”

“It seems a singularly useless thing to steal,” said

Sherlock Holmes. “I confess that I share Dr. Mortimer’s belief that it will not

be long before the missing boot is found.” “It seems a singularly useless thing to steal,” said

Sherlock Holmes. “I confess that I share Dr. Mortimer’s belief that it will not

be long before the missing boot is found.”

“And, now, gentlemen,” said the baronet with

decision, “it seems to me that I have spoken quite enough about the little that I

know. It is time that you kept your promise and gave me a full account of what we are all

driving at.” “And, now, gentlemen,” said the baronet with

decision, “it seems to me that I have spoken quite enough about the little that I

know. It is time that you kept your promise and gave me a full account of what we are all

driving at.”

[689]

“Your request is a very reasonable one,” Holmes answered. “Dr. Mortimer, I

think you could not do better than to tell your story as you told it to us.” [689]

“Your request is a very reasonable one,” Holmes answered. “Dr. Mortimer, I

think you could not do better than to tell your story as you told it to us.”

Thus encouraged, our scientific friend drew his papers from

his pocket and presented the whole case as he had done upon the morning before. Sir Henry

Baskerville listened with the deepest attention and with an occasional exclamation of

surprise. Thus encouraged, our scientific friend drew his papers from

his pocket and presented the whole case as he had done upon the morning before. Sir Henry

Baskerville listened with the deepest attention and with an occasional exclamation of

surprise.

“Well, I seem to have come into an inheritance with a

vengeance,” said he when the long narrative was finished. “Of course, I’ve

heard of the hound ever since I was in the nursery. It’s the pet story of the family,

though I never thought of taking it seriously before. But as to my uncle’s

death–well, it all seems boiling up in my head, and I can’t get it clear yet.

You don’t seem quite to have made up your mind whether it’s a case for a

policeman or a clergyman.” “Well, I seem to have come into an inheritance with a

vengeance,” said he when the long narrative was finished. “Of course, I’ve

heard of the hound ever since I was in the nursery. It’s the pet story of the family,

though I never thought of taking it seriously before. But as to my uncle’s

death–well, it all seems boiling up in my head, and I can’t get it clear yet.

You don’t seem quite to have made up your mind whether it’s a case for a

policeman or a clergyman.”

“Precisely.” “Precisely.”

“And now there’s this affair of the letter to me at

the hotel. I suppose that fits into its place.” “And now there’s this affair of the letter to me at

the hotel. I suppose that fits into its place.”

“It seems to show that someone knows more than we do

about what goes on upon the moor,” said Dr. Mortimer. “It seems to show that someone knows more than we do

about what goes on upon the moor,” said Dr. Mortimer.

“And also,” said Holmes, “that someone is not

ill-disposed towards you, since they warn you of danger.” “And also,” said Holmes, “that someone is not

ill-disposed towards you, since they warn you of danger.”

“Or it may be that they wish, for their own purposes, to

scare me away.” “Or it may be that they wish, for their own purposes, to

scare me away.”

“Well, of course, that is possible also. I am very much

indebted to you, Dr. Mortimer, for introducing me to a problem which presents several

interesting alternatives. But the practical point which we now have to decide, Sir Henry,

is whether it is or is not advisable for you to go to Baskerville Hall.” “Well, of course, that is possible also. I am very much

indebted to you, Dr. Mortimer, for introducing me to a problem which presents several

interesting alternatives. But the practical point which we now have to decide, Sir Henry,

is whether it is or is not advisable for you to go to Baskerville Hall.”

“Why should I not go?” “Why should I not go?”

“There seems to be danger.” “There seems to be danger.”

“Do you mean danger from this family fiend or do you mean

danger from human beings?” “Do you mean danger from this family fiend or do you mean

danger from human beings?”

“Well, that is what we have to find out.” “Well, that is what we have to find out.”

“Whichever it is, my answer is fixed. There is no devil

in hell, Mr. Holmes, and there is no man upon earth who can prevent me from going to the

home of my own people, and you may take that to be my final answer.” His dark brows

knitted and his face flushed to a dusky red as he spoke. It was evident that the fiery

temper of the Baskervilles was not extinct in this their last representative.

“Meanwhile,” said he, “I have hardly had time to think over all that you

have told me. It’s a big thing for a man to have to understand and to decide at one

sitting. I should like to have a quiet hour by myself to make up my mind. Now, look here,

Mr. Holmes, it’s half-past eleven now and I am going back right away to my hotel.

Suppose you and your friend, Dr. Watson, come round and lunch with us at two. I’ll be

able to tell you more clearly then how this thing strikes me.” “Whichever it is, my answer is fixed. There is no devil

in hell, Mr. Holmes, and there is no man upon earth who can prevent me from going to the

home of my own people, and you may take that to be my final answer.” His dark brows

knitted and his face flushed to a dusky red as he spoke. It was evident that the fiery

temper of the Baskervilles was not extinct in this their last representative.

“Meanwhile,” said he, “I have hardly had time to think over all that you

have told me. It’s a big thing for a man to have to understand and to decide at one

sitting. I should like to have a quiet hour by myself to make up my mind. Now, look here,

Mr. Holmes, it’s half-past eleven now and I am going back right away to my hotel.

Suppose you and your friend, Dr. Watson, come round and lunch with us at two. I’ll be

able to tell you more clearly then how this thing strikes me.”

“Is that convenient to you, Watson?” “Is that convenient to you, Watson?”

“Perfectly.” “Perfectly.”

“Then you may expect us. Shall I have a cab called?” “Then you may expect us. Shall I have a cab called?”

“I’d prefer to walk, for this affair has flurried me

rather.” “I’d prefer to walk, for this affair has flurried me

rather.”

“I’ll join you in a walk, with pleasure,” said

his companion. “I’ll join you in a walk, with pleasure,” said

his companion.

“Then we meet again at two o’clock. Au revoir, and

good-morning!” “Then we meet again at two o’clock. Au revoir, and

good-morning!”

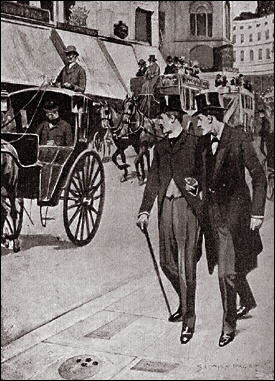

We heard the steps of our visitors descend the stair and the

bang of the front door. In an instant Holmes had changed from the languid dreamer to the

man of action. We heard the steps of our visitors descend the stair and the

bang of the front door. In an instant Holmes had changed from the languid dreamer to the

man of action.

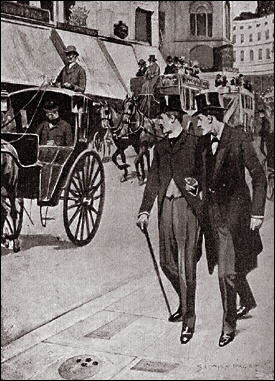

[690]

“Your hat and boots, Watson, quick! Not a moment to lose!” He rushed into his

room in his dressing-gown and was back again in a few seconds in a frock-coat. We hurried

together down the stairs and into the street. Dr. Mortimer and Baskerville were still

visible about two hundred yards ahead of us in the direction of Oxford Street. [690]

“Your hat and boots, Watson, quick! Not a moment to lose!” He rushed into his

room in his dressing-gown and was back again in a few seconds in a frock-coat. We hurried

together down the stairs and into the street. Dr. Mortimer and Baskerville were still

visible about two hundred yards ahead of us in the direction of Oxford Street.

“Shall I run on and stop them?” “Shall I run on and stop them?”

“Not for the world, my dear Watson. I am perfectly

satisfied with your company if you will tolerate mine. Our friends are wise, for it is

certainly a very fine morning for a walk.” “Not for the world, my dear Watson. I am perfectly

satisfied with your company if you will tolerate mine. Our friends are wise, for it is

certainly a very fine morning for a walk.”

He quickened his pace until we had decreased the distance

which divided us by about half. Then, still keeping a hundred yards behind, we followed

into Oxford Street and so down Regent Street. Once our friends stopped and stared into a

shop window, upon which Holmes did the same. An instant afterwards he gave a little cry of

satisfaction, and, following the direction of his eager eyes, I saw that a hansom cab with

a man inside which had halted on the other side of the street was now proceeding slowly

onward again. He quickened his pace until we had decreased the distance

which divided us by about half. Then, still keeping a hundred yards behind, we followed

into Oxford Street and so down Regent Street. Once our friends stopped and stared into a

shop window, upon which Holmes did the same. An instant afterwards he gave a little cry of

satisfaction, and, following the direction of his eager eyes, I saw that a hansom cab with

a man inside which had halted on the other side of the street was now proceeding slowly

onward again.

“There’s our man, Watson! Come along! We’ll

have a good look at him, if we can do no more.” “There’s our man, Watson! Come along! We’ll

have a good look at him, if we can do no more.”

At that instant I was aware of a bushy black beard and a

pair of piercing eyes turned upon us through the side window of the cab. Instantly the

trapdoor at the top flew up, something was screamed to the driver, and the cab flew madly

off down Regent Street. Holmes looked eagerly round for another, but no empty one was in

sight. Then he dashed in wild pursuit amid the stream of the traffic, but the start was

too great, and already the cab was out of sight. At that instant I was aware of a bushy black beard and a

pair of piercing eyes turned upon us through the side window of the cab. Instantly the

trapdoor at the top flew up, something was screamed to the driver, and the cab flew madly

off down Regent Street. Holmes looked eagerly round for another, but no empty one was in

sight. Then he dashed in wild pursuit amid the stream of the traffic, but the start was

too great, and already the cab was out of sight.

“There now!” said Holmes bitterly as he emerged

panting and white with vexation from the tide of vehicles. “Was ever such bad luck

and such bad management, too? Watson, Watson, if you are an honest man you will record

this also and set it against my successes!” “There now!” said Holmes bitterly as he emerged

panting and white with vexation from the tide of vehicles. “Was ever such bad luck

and such bad management, too? Watson, Watson, if you are an honest man you will record

this also and set it against my successes!”

“Who was the man?” “Who was the man?”

“I have not an idea.” “I have not an idea.”

“A spy?” “A spy?”

“Well, it was evident from what we have heard that

Baskerville has been very closely shadowed by someone since he has been in town. How else

could it be known so quickly that it was the Northumberland Hotel which he had chosen? If

they had followed him the first day I argued that they would follow him also the second.

You may have observed that I twice strolled over to the window while Dr. Mortimer was

reading his legend.” “Well, it was evident from what we have heard that

Baskerville has been very closely shadowed by someone since he has been in town. How else

could it be known so quickly that it was the Northumberland Hotel which he had chosen? If

they had followed him the first day I argued that they would follow him also the second.

You may have observed that I twice strolled over to the window while Dr. Mortimer was

reading his legend.”

“Yes, I remember.” “Yes, I remember.”

“I was looking out for loiterers in the street, but I saw

none. We are dealing with a clever man, Watson. This matter cuts very deep, and though I

have not finally made up my mind whether it is a benevolent or a malevolent agency which

is in touch with us, I am conscious always of power and design. When our friends left I at

once followed them in the hopes of marking down their invisible attendant. So wily was he

that he had not trusted himself upon foot, but he had availed himself of a cab so that he

could loiter behind or dash past them and so escape their notice. His method had the

additional advantage that if they were to take a cab he was all ready to follow them. It

has, however, one obvious disadvantage.” “I was looking out for loiterers in the street, but I saw

none. We are dealing with a clever man, Watson. This matter cuts very deep, and though I

have not finally made up my mind whether it is a benevolent or a malevolent agency which

is in touch with us, I am conscious always of power and design. When our friends left I at

once followed them in the hopes of marking down their invisible attendant. So wily was he

that he had not trusted himself upon foot, but he had availed himself of a cab so that he

could loiter behind or dash past them and so escape their notice. His method had the

additional advantage that if they were to take a cab he was all ready to follow them. It

has, however, one obvious disadvantage.”

“It puts him in the power of the cabman.” “It puts him in the power of the cabman.”

“Exactly.” “Exactly.”

[691]

“What a pity we did not get the number!” [691]

“What a pity we did not get the number!”

“My dear Watson, clumsy as I have been, you surely do not

seriously imagine that I neglected to get the number? No. 2704 is our man. But that is no

use to us for the moment.” “My dear Watson, clumsy as I have been, you surely do not

seriously imagine that I neglected to get the number? No. 2704 is our man. But that is no

use to us for the moment.”

“I fail to see how you could have done more.” “I fail to see how you could have done more.”

“On observing the cab I should have instantly turned and

walked in the other direction. I should then at my leisure have hired a second cab and

followed the first at a respectful distance, or, better still, have driven to the

Northumberland Hotel and waited there. When our unknown had followed Baskerville home we

should have had the opportunity of playing his own game upon himself and seeing where he

made for. As it is, by an indiscreet eagerness, which was taken advantage of with

extraordinary quickness and energy by our opponent, we have betrayed ourselves and lost

our man.” “On observing the cab I should have instantly turned and

walked in the other direction. I should then at my leisure have hired a second cab and

followed the first at a respectful distance, or, better still, have driven to the

Northumberland Hotel and waited there. When our unknown had followed Baskerville home we

should have had the opportunity of playing his own game upon himself and seeing where he

made for. As it is, by an indiscreet eagerness, which was taken advantage of with

extraordinary quickness and energy by our opponent, we have betrayed ourselves and lost

our man.”

We had been sauntering slowly down Regent Street during this

conversation, and Dr. Mortimer, with his companion, had long vanished in front of us. We had been sauntering slowly down Regent Street during this

conversation, and Dr. Mortimer, with his companion, had long vanished in front of us.

“There is no object in our following them,” said

Holmes. “The shadow has departed and will not return. We must see what further cards

we have in our hands and play them with decision. Could you swear to that man’s face

within the cab?” “There is no object in our following them,” said

Holmes. “The shadow has departed and will not return. We must see what further cards

we have in our hands and play them with decision. Could you swear to that man’s face

within the cab?”

“I could swear only to the beard.” “I could swear only to the beard.”

“And so could I–from which I gather that in all

probability it was a false one. A clever man upon so delicate an errand has no use for a

beard save to conceal his features. Come in here, Watson!” “And so could I–from which I gather that in all

probability it was a false one. A clever man upon so delicate an errand has no use for a

beard save to conceal his features. Come in here, Watson!”

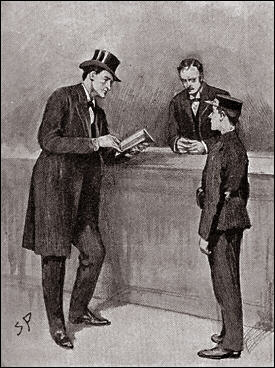

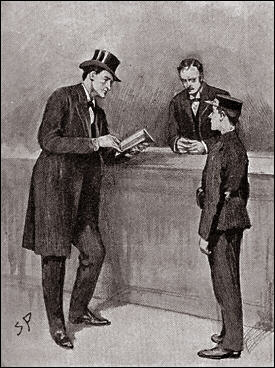

He turned into one of the district messenger offices, where he

was warmly greeted by the manager. He turned into one of the district messenger offices, where he

was warmly greeted by the manager.

“Ah, Wilson, I see you have not forgotten the little case

in which I had the good fortune to help you?” “Ah, Wilson, I see you have not forgotten the little case

in which I had the good fortune to help you?”

“No, sir, indeed I have not. You saved my good name, and

perhaps my life.” “No, sir, indeed I have not. You saved my good name, and

perhaps my life.”

“My dear fellow, you exaggerate. I have some

recollection, Wilson, that you had among your boys a lad named Cartwright, who showed some

ability during the investigation.” “My dear fellow, you exaggerate. I have some

recollection, Wilson, that you had among your boys a lad named Cartwright, who showed some

ability during the investigation.”

“Yes, sir, he is still with us.” “Yes, sir, he is still with us.”

“Could you ring him up?–thank you! And I should be

glad to have change of this five-pound note.” “Could you ring him up?–thank you! And I should be

glad to have change of this five-pound note.”

A lad of fourteen, with a bright, keen face, had obeyed the

summons of the manager. He stood now gazing with great reverence at the famous detective. A lad of fourteen, with a bright, keen face, had obeyed the

summons of the manager. He stood now gazing with great reverence at the famous detective.

“Let me have the Hotel Directory,” said Holmes.

“Thank you! Now, Cartwright, there are the names of twenty-three hotels here, all in

the immediate neighbourhood of Charing Cross. Do you see?” “Let me have the Hotel Directory,” said Holmes.

“Thank you! Now, Cartwright, there are the names of twenty-three hotels here, all in

the immediate neighbourhood of Charing Cross. Do you see?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“You will visit each of these in turn.” “You will visit each of these in turn.”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“You will begin in each case by giving the outside porter

one shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings.” “You will begin in each case by giving the outside porter

one shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings.”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“You will tell him that you want to see the waste-paper

of yesterday. You will say that an important telegram has miscarried and that you are

looking for it. You understand?” “You will tell him that you want to see the waste-paper

of yesterday. You will say that an important telegram has miscarried and that you are

looking for it. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“But what you are really looking for is the centre page

of the Times with some [692]

holes cut in it with scissors. Here is a copy of the Times. It is this page. You

could easily recognize it, could you not?” “But what you are really looking for is the centre page

of the Times with some [692]

holes cut in it with scissors. Here is a copy of the Times. It is this page. You

could easily recognize it, could you not?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“In each case the outside porter will send for the

hall porter, to whom also you will give a shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings. You

will then learn in possibly twenty cases out of the twenty-three that the waste of the day

before has been burned or removed. In the three other cases you will be shown a heap of

paper and you will look for this page of the Times among it. The odds are

enormously against your finding it. There are ten shillings over in case of emergencies.

Let me have a report by wire at Baker Street before evening. And now, Watson, it only

remains for us to find out by wire the identity of the cabman, No. 2704, and then we will

drop into one of the Bond Street picture galleries and fill in the time until we are due

at the hotel.” “In each case the outside porter will send for the

hall porter, to whom also you will give a shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings. You

will then learn in possibly twenty cases out of the twenty-three that the waste of the day

before has been burned or removed. In the three other cases you will be shown a heap of

paper and you will look for this page of the Times among it. The odds are

enormously against your finding it. There are ten shillings over in case of emergencies.

Let me have a report by wire at Baker Street before evening. And now, Watson, it only

remains for us to find out by wire the identity of the cabman, No. 2704, and then we will

drop into one of the Bond Street picture galleries and fill in the time until we are due

at the hotel.”

|

![]() “This is Sir Henry Baskerville,” said Dr.

Mortimer.

“This is Sir Henry Baskerville,” said Dr.

Mortimer.![]() “Why, yes,” said he, “and the strange thing is,

Mr. Sherlock Holmes, that if my friend here had not proposed coming round to you this

morning I should have come on my own account. I understand that you think out little

puzzles, and I’ve had one this morning which wants more thinking out than I am able

to give it.”

“Why, yes,” said he, “and the strange thing is,

Mr. Sherlock Holmes, that if my friend here had not proposed coming round to you this

morning I should have come on my own account. I understand that you think out little

puzzles, and I’ve had one this morning which wants more thinking out than I am able

to give it.”![]() “Pray take a seat, Sir Henry. Do I understand you to say

that you have yourself had some remarkable experience since you arrived in London?”

“Pray take a seat, Sir Henry. Do I understand you to say

that you have yourself had some remarkable experience since you arrived in London?”![]() “Nothing of much importance, Mr. Holmes. Only a joke, as

like as not. It was this letter, if you can call it a letter, which reached me this

morning.”

“Nothing of much importance, Mr. Holmes. Only a joke, as

like as not. It was this letter, if you can call it a letter, which reached me this

morning.”![]() He laid an envelope upon the table, and we all bent over it.

It was of common quality, grayish in colour. The address, “Sir Henry Baskerville,

Northumberland Hotel,” was printed in rough characters; the post-mark “Charing

Cross,” and the date of posting the preceding evening.

He laid an envelope upon the table, and we all bent over it.

It was of common quality, grayish in colour. The address, “Sir Henry Baskerville,

Northumberland Hotel,” was printed in rough characters; the post-mark “Charing

Cross,” and the date of posting the preceding evening.![]() “Who knew that you were going to the Northumberland

Hotel?” asked Holmes, glancing keenly across at our visitor.

“Who knew that you were going to the Northumberland

Hotel?” asked Holmes, glancing keenly across at our visitor.![]() “No one could have known. We only decided after I met Dr.

Mortimer.”

“No one could have known. We only decided after I met Dr.

Mortimer.”![]() “But Dr. Mortimer was no doubt already stopping

there?”

“But Dr. Mortimer was no doubt already stopping

there?”![]() “No, I had been staying with a friend,” said the

doctor. “There was no possible indication that we intended to go to this hotel.”

“No, I had been staying with a friend,” said the

doctor. “There was no possible indication that we intended to go to this hotel.”![]() “Hum! Someone seems to be very deeply interested in your

movements.” Out of the envelope he took a half-sheet of foolscap paper folded into

four. This he opened and spread flat upon the table. Across the middle of it a single

sentence had been formed by the expedient of pasting printed words upon it. It ran:

“Hum! Someone seems to be very deeply interested in your

movements.” Out of the envelope he took a half-sheet of foolscap paper folded into

four. This he opened and spread flat upon the table. Across the middle of it a single

sentence had been formed by the expedient of pasting printed words upon it. It ran: