|

|

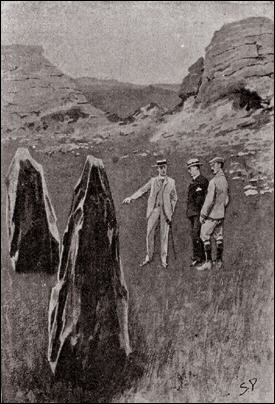

He came over to call upon Baskerville on that first day, and

the very next morning he took us both to show us the spot where the legend of the wicked

Hugo is supposed to have had its origin. It was an excursion of some miles across the moor

to a place which is so dismal that it might have suggested the story. We found a short

valley between rugged tors which led to an open, grassy space flecked over with the white

cotton grass. In the middle of it rose two great stones, worn and sharpened at the upper

end until they looked like the huge corroding fangs of some monstrous beast. In every way

it corresponded with the scene of the old tragedy. Sir Henry was much interested and asked

Stapleton more than once whether he did really believe in the possibility of the

interference of the supernatural [714] in

the affairs of men. He spoke lightly, but it was evident that he was very much in earnest.

Stapleton was guarded in his replies, but it was easy to see that he said less than he

might, and that he would not express his whole opinion out of consideration for the

feelings of the baronet. He told us of similar cases, where families had suffered from

some evil influence, and he left us with the impression that he shared the popular view

upon the matter. He came over to call upon Baskerville on that first day, and

the very next morning he took us both to show us the spot where the legend of the wicked

Hugo is supposed to have had its origin. It was an excursion of some miles across the moor

to a place which is so dismal that it might have suggested the story. We found a short

valley between rugged tors which led to an open, grassy space flecked over with the white

cotton grass. In the middle of it rose two great stones, worn and sharpened at the upper

end until they looked like the huge corroding fangs of some monstrous beast. In every way

it corresponded with the scene of the old tragedy. Sir Henry was much interested and asked

Stapleton more than once whether he did really believe in the possibility of the

interference of the supernatural [714] in

the affairs of men. He spoke lightly, but it was evident that he was very much in earnest.

Stapleton was guarded in his replies, but it was easy to see that he said less than he

might, and that he would not express his whole opinion out of consideration for the

feelings of the baronet. He told us of similar cases, where families had suffered from

some evil influence, and he left us with the impression that he shared the popular view

upon the matter.

On our way back we stayed for lunch at Merripit House, and it

was there that Sir Henry made the acquaintance of Miss Stapleton. From the first moment

that he saw her he appeared to be strongly attracted by her, and I am much mistaken if the

feeling was not mutual. He referred to her again and again on our walk home, and since

then hardly a day has passed that we have not seen something of the brother and sister.

They dine here to-night, and there is some talk of our going to them next week. One would

imagine that such a match would be very welcome to Stapleton, and yet I have more than

once caught a look of the strongest disapprobation in his face when Sir Henry has been

paying some attention to his sister. He is much attached to her, no doubt, and would lead

a lonely life without her, but it would seem the height of selfishness if he were to stand

in the way of her making so brilliant a marriage. Yet I am certain that he does not wish

their intimacy to ripen into love, and I have several times observed that he has taken

pains to prevent them from being tete-a-tete. By the way, your instructions to me never to

allow Sir Henry to go out alone will become very much more onerous if a love affair were

to be added to our other difficulties. My popularity would soon suffer if I were to carry

out your orders to the letter. On our way back we stayed for lunch at Merripit House, and it

was there that Sir Henry made the acquaintance of Miss Stapleton. From the first moment

that he saw her he appeared to be strongly attracted by her, and I am much mistaken if the

feeling was not mutual. He referred to her again and again on our walk home, and since

then hardly a day has passed that we have not seen something of the brother and sister.

They dine here to-night, and there is some talk of our going to them next week. One would

imagine that such a match would be very welcome to Stapleton, and yet I have more than

once caught a look of the strongest disapprobation in his face when Sir Henry has been

paying some attention to his sister. He is much attached to her, no doubt, and would lead

a lonely life without her, but it would seem the height of selfishness if he were to stand

in the way of her making so brilliant a marriage. Yet I am certain that he does not wish

their intimacy to ripen into love, and I have several times observed that he has taken

pains to prevent them from being tete-a-tete. By the way, your instructions to me never to

allow Sir Henry to go out alone will become very much more onerous if a love affair were

to be added to our other difficulties. My popularity would soon suffer if I were to carry

out your orders to the letter.

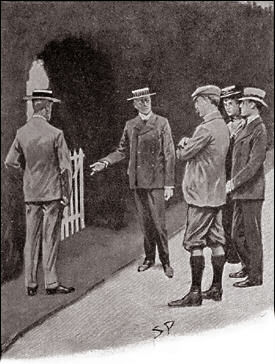

The other day–Thursday, to be more exact–Dr.

Mortimer lunched with us. He has been excavating a barrow at Long Down and has got a

prehistoric skull which fills him with great joy. Never was there such a single-minded

enthusiast as he! The Stapletons came in afterwards, and the good doctor took us all to

the yew alley at Sir Henry’s request to show us exactly how everything occurred upon

that fatal night. It is a long, dismal walk, the yew alley, between two high walls of

clipped hedge, with a narrow band of grass upon either side. At the far end is an old

tumble-down summer-house. Halfway down is the moor-gate, where the old gentleman left his

cigar-ash. It is a white wooden gate with a latch. Beyond it lies the wide moor. I

remembered your theory of the affair and tried to picture all that had occurred. As the

old man stood there he saw something coming across the moor, something which terrified him

so that he lost his wits and ran and ran until he died of sheer horror and exhaustion.

There was the long, gloomy tunnel down which he fled. And from what? A sheep-dog of the

moor? Or a spectral hound, black, silent, and monstrous? Was there a human agency in the

matter? Did the pale, watchful Barrymore know more than he cared to say? It was all dim

and vague, but always there is the dark shadow of crime behind it. The other day–Thursday, to be more exact–Dr.

Mortimer lunched with us. He has been excavating a barrow at Long Down and has got a

prehistoric skull which fills him with great joy. Never was there such a single-minded

enthusiast as he! The Stapletons came in afterwards, and the good doctor took us all to

the yew alley at Sir Henry’s request to show us exactly how everything occurred upon

that fatal night. It is a long, dismal walk, the yew alley, between two high walls of

clipped hedge, with a narrow band of grass upon either side. At the far end is an old

tumble-down summer-house. Halfway down is the moor-gate, where the old gentleman left his

cigar-ash. It is a white wooden gate with a latch. Beyond it lies the wide moor. I

remembered your theory of the affair and tried to picture all that had occurred. As the

old man stood there he saw something coming across the moor, something which terrified him

so that he lost his wits and ran and ran until he died of sheer horror and exhaustion.

There was the long, gloomy tunnel down which he fled. And from what? A sheep-dog of the

moor? Or a spectral hound, black, silent, and monstrous? Was there a human agency in the

matter? Did the pale, watchful Barrymore know more than he cared to say? It was all dim

and vague, but always there is the dark shadow of crime behind it.

One other neighbour I have met since I wrote last. This is

Mr. Frankland, of Lafter Hall, who lives some four miles to the south of us. He is an

elderly man, red-faced, white-haired, and choleric. His passion is for the British law,

and he has spent a large fortune in litigation. He fights for the mere pleasure of

fighting and is equally ready to take up either side of a question, so that it is no

wonder that he has found it a costly amusement. Sometimes he will shut up a right of way

and defy the parish to make him open it. At others he will with his own hands tear down

some other man’s gate and declare that a path has existed there from time immemorial,

defying the owner to prosecute him for trespass. He is learned in [715] old manorial and communal rights,

and he applies his knowledge sometimes in favour of the villagers of Fernworthy and

sometimes against them, so that he is periodically either carried in triumph down the

village street or else burned in effigy, according to his latest exploit. He is said to

have about seven lawsuits upon his hands at present, which will probably swallow up the

remainder of his fortune and so draw his sting and leave him harmless for the future.

Apart from the law he seems a kindly, good-natured person, and I only mention him because

you were particular that I should send some description of the people who surround us. He

is curiously employed at present, for, being an amateur astronomer, he has an excellent

telescope, with which he lies upon the roof of his own house and sweeps the moor all day

in the hope of catching a glimpse of the escaped convict. If he would confine his energies

to this all would be well, but there are rumours that he intends to prosecute Dr. Mortimer

for opening a grave without the consent of the next of kin because he dug up the neolithic

skull in the barrow on Long Down. He helps to keep our lives from being monotonous and

gives a little comic relief where it is badly needed. One other neighbour I have met since I wrote last. This is

Mr. Frankland, of Lafter Hall, who lives some four miles to the south of us. He is an

elderly man, red-faced, white-haired, and choleric. His passion is for the British law,

and he has spent a large fortune in litigation. He fights for the mere pleasure of

fighting and is equally ready to take up either side of a question, so that it is no

wonder that he has found it a costly amusement. Sometimes he will shut up a right of way

and defy the parish to make him open it. At others he will with his own hands tear down

some other man’s gate and declare that a path has existed there from time immemorial,

defying the owner to prosecute him for trespass. He is learned in [715] old manorial and communal rights,

and he applies his knowledge sometimes in favour of the villagers of Fernworthy and

sometimes against them, so that he is periodically either carried in triumph down the

village street or else burned in effigy, according to his latest exploit. He is said to

have about seven lawsuits upon his hands at present, which will probably swallow up the

remainder of his fortune and so draw his sting and leave him harmless for the future.

Apart from the law he seems a kindly, good-natured person, and I only mention him because

you were particular that I should send some description of the people who surround us. He

is curiously employed at present, for, being an amateur astronomer, he has an excellent

telescope, with which he lies upon the roof of his own house and sweeps the moor all day

in the hope of catching a glimpse of the escaped convict. If he would confine his energies

to this all would be well, but there are rumours that he intends to prosecute Dr. Mortimer

for opening a grave without the consent of the next of kin because he dug up the neolithic

skull in the barrow on Long Down. He helps to keep our lives from being monotonous and

gives a little comic relief where it is badly needed.

And now, having brought you up to date in the escaped convict,

the Stapletons, Dr. Mortimer, and Frankland, of Lafter Hall, let me end on that which is

most important and tell you more about the Barrymores, and especially about the surprising

development of last night. And now, having brought you up to date in the escaped convict,

the Stapletons, Dr. Mortimer, and Frankland, of Lafter Hall, let me end on that which is

most important and tell you more about the Barrymores, and especially about the surprising

development of last night.

First of all about the test telegram, which you sent from

London in order to make sure that Barrymore was really here. I have already explained that

the testimony of the postmaster shows that the test was worthless and that we have no

proof one way or the other. I told Sir Henry how the matter stood, and he at once, in his

downright fashion, had Barrymore up and asked him whether he had received the telegram

himself. Barrymore said that he had. First of all about the test telegram, which you sent from

London in order to make sure that Barrymore was really here. I have already explained that

the testimony of the postmaster shows that the test was worthless and that we have no

proof one way or the other. I told Sir Henry how the matter stood, and he at once, in his

downright fashion, had Barrymore up and asked him whether he had received the telegram

himself. Barrymore said that he had.

“Did the boy deliver it into your own hands?” asked

Sir Henry. “Did the boy deliver it into your own hands?” asked

Sir Henry.

Barrymore looked surprised, and considered for a little time. Barrymore looked surprised, and considered for a little time.

“No,” said he, “I was in the box-room at the

time, and my wife brought it up to me.” “No,” said he, “I was in the box-room at the

time, and my wife brought it up to me.”

“Did you answer it yourself?” “Did you answer it yourself?”

“No; I told my wife what to answer and she went down to

write it.” “No; I told my wife what to answer and she went down to

write it.”

In the evening he recurred to the subject of his own accord. In the evening he recurred to the subject of his own accord.

“I could not quite understand the object of your

questions this morning, Sir Henry,” said he. “I trust that they do not mean that

I have done anything to forfeit your confidence?” “I could not quite understand the object of your

questions this morning, Sir Henry,” said he. “I trust that they do not mean that

I have done anything to forfeit your confidence?”

Sir Henry had to assure him that it was not so and pacify him

by giving him a considerable part of his old wardrobe, the London outfit having now all

arrived. Sir Henry had to assure him that it was not so and pacify him

by giving him a considerable part of his old wardrobe, the London outfit having now all

arrived.

Mrs. Barrymore is of interest to me. She is a heavy, solid

person, very limited, intensely respectable, and inclined to be puritanical. You could

hardly conceive a less emotional subject. Yet I have told you how, on the first night

here, I heard her sobbing bitterly, and since then I have more than once observed traces

of tears upon her face. Some deep sorrow gnaws ever at her heart. Sometimes I wonder if

she has a guilty memory which haunts her, and sometimes I suspect Barrymore of being a

domestic tyrant. I have always felt that there was something singular and questionable in

this man’s character, but the adventure of last night brings all my suspicions to a

head. Mrs. Barrymore is of interest to me. She is a heavy, solid

person, very limited, intensely respectable, and inclined to be puritanical. You could

hardly conceive a less emotional subject. Yet I have told you how, on the first night

here, I heard her sobbing bitterly, and since then I have more than once observed traces

of tears upon her face. Some deep sorrow gnaws ever at her heart. Sometimes I wonder if

she has a guilty memory which haunts her, and sometimes I suspect Barrymore of being a

domestic tyrant. I have always felt that there was something singular and questionable in

this man’s character, but the adventure of last night brings all my suspicions to a

head.

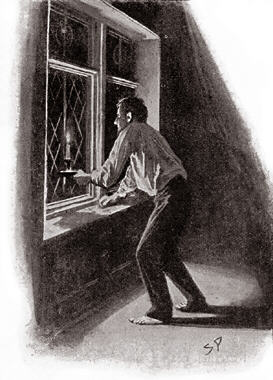

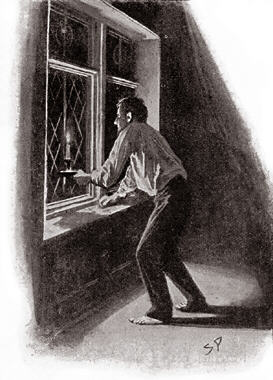

And yet it may seem a small matter in itself. You are aware

that I am not a very sound sleeper, and since I have been on guard in this house my

slumbers have [716] been

lighter than ever. Last night, about two in the morning, I was aroused by a stealthy step

passing my room. I rose, opened my door, and peeped out. A long black shadow was trailing

down the corridor. It was thrown by a man who walked softly down the passage with a candle

held in his hand. He was in shirt and trousers, with no covering to his feet. I could

merely see the outline, but his height told me that it was Barrymore. He walked very

slowly and circumspectly, and there was something indescribably guilty and furtive in his

whole appearance. And yet it may seem a small matter in itself. You are aware

that I am not a very sound sleeper, and since I have been on guard in this house my

slumbers have [716] been

lighter than ever. Last night, about two in the morning, I was aroused by a stealthy step

passing my room. I rose, opened my door, and peeped out. A long black shadow was trailing

down the corridor. It was thrown by a man who walked softly down the passage with a candle

held in his hand. He was in shirt and trousers, with no covering to his feet. I could

merely see the outline, but his height told me that it was Barrymore. He walked very

slowly and circumspectly, and there was something indescribably guilty and furtive in his

whole appearance.

I have told you that the corridor is broken by the balcony

which runs round the hall, but that it is resumed upon the farther side. I waited until he

had passed out of sight and then I followed him. When I came round the balcony he had

reached the end of the farther corridor, and I could see from the glimmer of light through

an open door that he had entered one of the rooms. Now, all these rooms are unfurnished

and unoccupied, so that his expedition became more mysterious than ever. The light shone

steadily as if he were standing motionless. I crept down the passage as noiselessly as I

could and peeped round the corner of the door. I have told you that the corridor is broken by the balcony

which runs round the hall, but that it is resumed upon the farther side. I waited until he

had passed out of sight and then I followed him. When I came round the balcony he had

reached the end of the farther corridor, and I could see from the glimmer of light through

an open door that he had entered one of the rooms. Now, all these rooms are unfurnished

and unoccupied, so that his expedition became more mysterious than ever. The light shone

steadily as if he were standing motionless. I crept down the passage as noiselessly as I

could and peeped round the corner of the door.

Barrymore was crouching at the window with the candle held

against the glass. His profile was half turned towards me, and his face seemed to be rigid

with expectation as he stared out into the blackness of the moor. For some minutes he

stood watching intently. Then he gave a deep groan and with an impatient gesture he put

out the light. Instantly I made my way back to my room, and very shortly came the stealthy

steps passing once more upon their return journey. Long afterwards when I had fallen into

a light sleep I heard a key turn somewhere in a lock, but I could not tell whence the

sound came. What it all means I cannot guess, but there is some secret business going on

in this house of gloom which sooner or later we shall get to the bottom of. I do not

trouble you with my theories, for you asked me to furnish you only with facts. I have had

a long talk with Sir Henry this morning, and we have made a plan of campaign founded upon

my observations of last night. I will not speak about it just now, but it should make my

next report interesting reading. Barrymore was crouching at the window with the candle held

against the glass. His profile was half turned towards me, and his face seemed to be rigid

with expectation as he stared out into the blackness of the moor. For some minutes he

stood watching intently. Then he gave a deep groan and with an impatient gesture he put

out the light. Instantly I made my way back to my room, and very shortly came the stealthy

steps passing once more upon their return journey. Long afterwards when I had fallen into

a light sleep I heard a key turn somewhere in a lock, but I could not tell whence the

sound came. What it all means I cannot guess, but there is some secret business going on

in this house of gloom which sooner or later we shall get to the bottom of. I do not

trouble you with my theories, for you asked me to furnish you only with facts. I have had

a long talk with Sir Henry this morning, and we have made a plan of campaign founded upon

my observations of last night. I will not speak about it just now, but it should make my

next report interesting reading.

|

My previous letters and telegrams have kept you pretty well up

to date as to all that has occurred in this most God-forsaken corner of the world. The

longer one stays here the more does the spirit of the moor sink into one’s soul, its

vastness, and also its grim charm. When you are once out upon its bosom you have left all

traces of modern England behind you, but, on the other hand, you are conscious everywhere

of the homes and the work of the prehistoric people. On all sides of you as you walk are

the houses of these forgotten folk, with their graves and the huge monoliths which are

supposed to have marked their temples. As you look at their gray stone huts against the

scarred hillsides you leave your own age behind you, and if you were to see a skin-clad,

hairy man crawl out from the low door, fitting a flint-tipped arrow on to the string of

his bow, you would feel that his presence there was more natural than your own. The

strange thing is that they should have lived so thickly on what must always have been most

[713] unfruitful soil. I am

no antiquarian, but I could imagine that they were some unwarlike and harried race who

were forced to accept that which none other would occupy.

My previous letters and telegrams have kept you pretty well up

to date as to all that has occurred in this most God-forsaken corner of the world. The

longer one stays here the more does the spirit of the moor sink into one’s soul, its

vastness, and also its grim charm. When you are once out upon its bosom you have left all

traces of modern England behind you, but, on the other hand, you are conscious everywhere

of the homes and the work of the prehistoric people. On all sides of you as you walk are

the houses of these forgotten folk, with their graves and the huge monoliths which are

supposed to have marked their temples. As you look at their gray stone huts against the

scarred hillsides you leave your own age behind you, and if you were to see a skin-clad,

hairy man crawl out from the low door, fitting a flint-tipped arrow on to the string of

his bow, you would feel that his presence there was more natural than your own. The

strange thing is that they should have lived so thickly on what must always have been most

[713] unfruitful soil. I am

no antiquarian, but I could imagine that they were some unwarlike and harried race who

were forced to accept that which none other would occupy. All this, however, is foreign to the mission on which you sent

me and will probably be very uninteresting to your severely practical mind. I can still

remember your complete indifference as to whether the sun moved round the earth or the

earth round the sun. Let me, therefore, return to the facts concerning Sir Henry

Baskerville.

All this, however, is foreign to the mission on which you sent

me and will probably be very uninteresting to your severely practical mind. I can still

remember your complete indifference as to whether the sun moved round the earth or the

earth round the sun. Let me, therefore, return to the facts concerning Sir Henry

Baskerville. If you have not had any report within the last few days it is

because up to to-day there was nothing of importance to relate. Then a very surprising

circumstance occurred, which I shall tell you in due course. But, first of all, I must

keep you in touch with some of the other factors in the situation.

If you have not had any report within the last few days it is

because up to to-day there was nothing of importance to relate. Then a very surprising

circumstance occurred, which I shall tell you in due course. But, first of all, I must

keep you in touch with some of the other factors in the situation. One of these, concerning which I have said little, is the

escaped convict upon the moor. There is strong reason now to believe that he has got right

away, which is a considerable relief to the lonely householders of this district. A

fortnight has passed since his flight, during which he has not been seen and nothing has

been heard of him. It is surely inconceivable that he could have held out upon the moor

during all that time. Of course, so far as his concealment goes there is no difficulty at

all. Any one of these stone huts would give him a hiding-place. But there is nothing to

eat unless he were to catch and slaughter one of the moor sheep. We think, therefore, that

he has gone, and the outlying farmers sleep the better in consequence.

One of these, concerning which I have said little, is the

escaped convict upon the moor. There is strong reason now to believe that he has got right

away, which is a considerable relief to the lonely householders of this district. A

fortnight has passed since his flight, during which he has not been seen and nothing has

been heard of him. It is surely inconceivable that he could have held out upon the moor

during all that time. Of course, so far as his concealment goes there is no difficulty at

all. Any one of these stone huts would give him a hiding-place. But there is nothing to

eat unless he were to catch and slaughter one of the moor sheep. We think, therefore, that

he has gone, and the outlying farmers sleep the better in consequence. We are four able-bodied men in this household, so that we

could take good care of ourselves, but I confess that I have had uneasy moments when I

have thought of the Stapletons. They live miles from any help. There are one maid, an old

manservant, the sister, and the brother, the latter not a very strong man. They would be

helpless in the hands of a desperate fellow like this Notting Hill criminal if he could

once effect an entrance. Both Sir Henry and I were concerned at their situation, and it

was suggested that Perkins the groom should go over to sleep there, but Stapleton would

not hear of it.

We are four able-bodied men in this household, so that we

could take good care of ourselves, but I confess that I have had uneasy moments when I

have thought of the Stapletons. They live miles from any help. There are one maid, an old

manservant, the sister, and the brother, the latter not a very strong man. They would be

helpless in the hands of a desperate fellow like this Notting Hill criminal if he could

once effect an entrance. Both Sir Henry and I were concerned at their situation, and it

was suggested that Perkins the groom should go over to sleep there, but Stapleton would

not hear of it. The fact is that our friend, the baronet, begins to display a

considerable interest in our fair neighbour. It is not to be wondered at, for time hangs

heavily in this lonely spot to an active man like him, and she is a very fascinating and

beautiful woman. There is something tropical and exotic about her which forms a singular

contrast to her cool and unemotional brother. Yet he also gives the idea of hidden fires.

He has certainly a very marked influence over her, for I have seen her continually glance

at him as she talked as if seeking approbation for what she said. I trust that he is kind

to her. There is a dry glitter in his eyes and a firm set of his thin lips, which goes

with a positive and possibly a harsh nature. You would find him an interesting study.

The fact is that our friend, the baronet, begins to display a

considerable interest in our fair neighbour. It is not to be wondered at, for time hangs

heavily in this lonely spot to an active man like him, and she is a very fascinating and

beautiful woman. There is something tropical and exotic about her which forms a singular

contrast to her cool and unemotional brother. Yet he also gives the idea of hidden fires.

He has certainly a very marked influence over her, for I have seen her continually glance

at him as she talked as if seeking approbation for what she said. I trust that he is kind

to her. There is a dry glitter in his eyes and a firm set of his thin lips, which goes

with a positive and possibly a harsh nature. You would find him an interesting study.