Chapter 12

DEATH ON THE MOOR

FOR a moment or two I sat breathless, hardly able to believe my ears.

Then my senses and my voice came back to me, while a crushing weight of responsibility

seemed in an instant to be lifted from my soul. That cold, incisive, ironical voice could

belong to but one man in all the world.

![]() “Holmes!” I cried–“Holmes!”

“Holmes!” I cried–“Holmes!”

![]() “Come out,” said he, “and please be careful

with the revolver.”

“Come out,” said he, “and please be careful

with the revolver.”

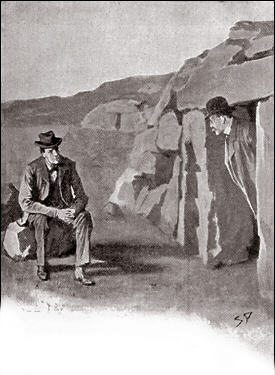

![]() I stooped under the rude lintel, and there he sat upon a

stone outside, his gray eyes dancing with amusement as they fell upon my astonished

features. He was thin and worn, but clear and alert, his keen face bronzed by the sun and

roughened by the wind. In his tweed suit and cloth cap he looked like any other tourist

upon the moor, and he had contrived, with that catlike love of personal cleanliness which

was one of his characteristics, that his chin should be as smooth and his linen as perfect

as if he were in Baker Street.

I stooped under the rude lintel, and there he sat upon a

stone outside, his gray eyes dancing with amusement as they fell upon my astonished

features. He was thin and worn, but clear and alert, his keen face bronzed by the sun and

roughened by the wind. In his tweed suit and cloth cap he looked like any other tourist

upon the moor, and he had contrived, with that catlike love of personal cleanliness which

was one of his characteristics, that his chin should be as smooth and his linen as perfect

as if he were in Baker Street.

![]() “I never was more glad to see anyone in my life,”

said I as I wrung him by the hand.

“I never was more glad to see anyone in my life,”

said I as I wrung him by the hand.

![]() “Or more astonished, eh?”

“Or more astonished, eh?”

![]() “Well, I must confess to it.”

“Well, I must confess to it.”

![]() “The surprise was not all on one side, I assure you. I

had no idea that you had found my occasional retreat, still less that you were inside it,

until I was within twenty paces of the door.”

“The surprise was not all on one side, I assure you. I

had no idea that you had found my occasional retreat, still less that you were inside it,

until I was within twenty paces of the door.”

![]() “My footprint, I presume?”

“My footprint, I presume?”

![]() “No, Watson; I fear that I could not undertake to

recognize your footprint amid all the footprints of the world. If you seriously desire to

deceive me you must change your tobacconist; for when I see the stub of a cigarette marked

Bradley, Oxford Street, I know that my friend Watson is in the neighbourhood. You will see

it there beside the path. You threw it down, no doubt, at that supreme moment when you

charged into the empty hut.”

“No, Watson; I fear that I could not undertake to

recognize your footprint amid all the footprints of the world. If you seriously desire to

deceive me you must change your tobacconist; for when I see the stub of a cigarette marked

Bradley, Oxford Street, I know that my friend Watson is in the neighbourhood. You will see

it there beside the path. You threw it down, no doubt, at that supreme moment when you

charged into the empty hut.”

![]() “Exactly.”

“Exactly.”

![]() “I thought as much–and knowing your admirable

tenacity I was convinced that you were sitting in ambush, a weapon within reach, waiting

for the tenant to return. So you actually thought that I was the criminal?”

“I thought as much–and knowing your admirable

tenacity I was convinced that you were sitting in ambush, a weapon within reach, waiting

for the tenant to return. So you actually thought that I was the criminal?”

![]() “I did not know who you were, but I was determined to

find out.”

“I did not know who you were, but I was determined to

find out.”

![]() “Excellent, Watson! And how did you localize me? You saw

me, perhaps, on the night of the convict hunt, when I was so imprudent as to allow the

moon to rise behind me?”

“Excellent, Watson! And how did you localize me? You saw

me, perhaps, on the night of the convict hunt, when I was so imprudent as to allow the

moon to rise behind me?”

![]() “Yes, I saw you then.”

“Yes, I saw you then.”

![]() “And have no doubt searched all the huts until you came

to this one?”

“And have no doubt searched all the huts until you came

to this one?”

![]() “No, your boy had been observed, and that gave me a guide

where to look.”

“No, your boy had been observed, and that gave me a guide

where to look.”

![]() “The old gentleman with the telescope, no doubt. I could

not make it out when first I saw the light flashing upon the lens.” He rose and

peeped into the hut. “Ha, I see that Cartwright has brought up some supplies.

What’s this paper? So you have been to Coombe Tracey, have you?”

“The old gentleman with the telescope, no doubt. I could

not make it out when first I saw the light flashing upon the lens.” He rose and

peeped into the hut. “Ha, I see that Cartwright has brought up some supplies.

What’s this paper? So you have been to Coombe Tracey, have you?”

![]() “Yes.”

“Yes.”

![]() [741] “To

see Mrs. Laura Lyons?”

[741] “To

see Mrs. Laura Lyons?”

![]() “Exactly.”

“Exactly.”

![]() “Well done! Our researches have evidently been running on

parallel lines, and when we unite our results I expect we shall have a fairly full

knowledge of the case.”

“Well done! Our researches have evidently been running on

parallel lines, and when we unite our results I expect we shall have a fairly full

knowledge of the case.”

![]() “Well, I am glad from my heart that you are here, for

indeed the responsibility and the mystery were both becoming too much for my nerves. But

how in the name of wonder did you come here, and what have you been doing? I thought that

you were in Baker Street working out that case of blackmailing.”

“Well, I am glad from my heart that you are here, for

indeed the responsibility and the mystery were both becoming too much for my nerves. But

how in the name of wonder did you come here, and what have you been doing? I thought that

you were in Baker Street working out that case of blackmailing.”

![]() “That was what I wished you to think.”

“That was what I wished you to think.”

![]() “Then you use me, and yet do not trust me!” I cried

with some bitterness. “I think that I have deserved better at your hands,

Holmes.”

“Then you use me, and yet do not trust me!” I cried

with some bitterness. “I think that I have deserved better at your hands,

Holmes.”

![]() “My dear fellow, you have been invaluable to me in this

as in many other cases, and I beg that you will forgive me if I have seemed to play a

trick upon you. In truth, it was partly for your own sake that I did it, and it was my

appreciation of the danger which you ran which led me to come down and examine the matter

for myself. Had I been with Sir Henry and you it is confident that my point of view would

have been the same as yours, and my presence would have warned our very formidable

opponents to be on their guard. As it is, I have been able to get about as I could not

possibly have done had I been living in the Hall, and I remain an unknown factor in the

business, ready to throw in all my weight at a critical moment.”

“My dear fellow, you have been invaluable to me in this

as in many other cases, and I beg that you will forgive me if I have seemed to play a

trick upon you. In truth, it was partly for your own sake that I did it, and it was my

appreciation of the danger which you ran which led me to come down and examine the matter

for myself. Had I been with Sir Henry and you it is confident that my point of view would

have been the same as yours, and my presence would have warned our very formidable

opponents to be on their guard. As it is, I have been able to get about as I could not

possibly have done had I been living in the Hall, and I remain an unknown factor in the

business, ready to throw in all my weight at a critical moment.”

![]() “But why keep me in the dark?”

“But why keep me in the dark?”

![]() “For you to know could not have helped us and might

possibly have led to my discovery. You would have wished to tell me something, or in your

kindness you would have brought me out some comfort or other, and so an unnecessary risk

would be run. I brought Cartwright down with me–you remember the little chap at the

express office–and he has seen after my simple wants: a loaf of bread and a clean

collar. What does man want more? He has given me an extra pair of eyes upon a very active

pair of feet, and both have been invaluable.”

“For you to know could not have helped us and might

possibly have led to my discovery. You would have wished to tell me something, or in your

kindness you would have brought me out some comfort or other, and so an unnecessary risk

would be run. I brought Cartwright down with me–you remember the little chap at the

express office–and he has seen after my simple wants: a loaf of bread and a clean

collar. What does man want more? He has given me an extra pair of eyes upon a very active

pair of feet, and both have been invaluable.”

![]() “Then my reports have all been wasted!”–My

voice trembled as I recalled the pains and the pride with which I had composed them.

“Then my reports have all been wasted!”–My

voice trembled as I recalled the pains and the pride with which I had composed them.

![]() Holmes took a bundle of papers from his pocket.

Holmes took a bundle of papers from his pocket.

![]() “Here are your reports, my dear fellow, and very well

thumbed, I assure you. I made excellent arrangements, and they are only delayed one day

upon their way. I must compliment you exceedingly upon the zeal and the intelligence which

you have shown over an extraordinarily difficult case.”

“Here are your reports, my dear fellow, and very well

thumbed, I assure you. I made excellent arrangements, and they are only delayed one day

upon their way. I must compliment you exceedingly upon the zeal and the intelligence which

you have shown over an extraordinarily difficult case.”

![]() I was still rather raw over the deception which had been

practised upon me, but the warmth of Holmes’s praise drove my anger from my mind. I

felt also in my heart that he was right in what he said and that it was really best for

our purpose that I should not have known that he was upon the moor.

I was still rather raw over the deception which had been

practised upon me, but the warmth of Holmes’s praise drove my anger from my mind. I

felt also in my heart that he was right in what he said and that it was really best for

our purpose that I should not have known that he was upon the moor.

![]() “That’s better,” said he, seeing the shadow

rise from my face. “And now tell me the result of your visit to Mrs. Laura

Lyons–it was not difficult for me to guess that it was to see her that you had gone,

for I am already aware that she is the one person in Coombe Tracey who might be of service

to us in the matter. In fact, if you had not gone to-day it is exceedingly probable that I

should have gone to-morrow.”

“That’s better,” said he, seeing the shadow

rise from my face. “And now tell me the result of your visit to Mrs. Laura

Lyons–it was not difficult for me to guess that it was to see her that you had gone,

for I am already aware that she is the one person in Coombe Tracey who might be of service

to us in the matter. In fact, if you had not gone to-day it is exceedingly probable that I

should have gone to-morrow.”

![]() The sun had set and dusk was settling over the moor. The air

had turned chill and we withdrew into the hut for warmth. There, sitting together in the

twilight, [742] I told

Holmes of my conversation with the lady. So interested was he that I had to repeat some of

it twice before he was satisfied.

The sun had set and dusk was settling over the moor. The air

had turned chill and we withdrew into the hut for warmth. There, sitting together in the

twilight, [742] I told

Holmes of my conversation with the lady. So interested was he that I had to repeat some of

it twice before he was satisfied.

![]() “This is most important,” said he when I had

concluded. “It fills up a gap which I had been unable to bridge in this most complex

affair. You are aware, perhaps, that a close intimacy exists between this lady and the man

Stapleton?”

“This is most important,” said he when I had

concluded. “It fills up a gap which I had been unable to bridge in this most complex

affair. You are aware, perhaps, that a close intimacy exists between this lady and the man

Stapleton?”

![]() “I did not know of a close intimacy.”

“I did not know of a close intimacy.”

![]() “There can be no doubt about the matter. They meet, they

write, there is a complete understanding between them. Now, this puts a very powerful

weapon into our hands. If I could only use it to detach his wife– –”

“There can be no doubt about the matter. They meet, they

write, there is a complete understanding between them. Now, this puts a very powerful

weapon into our hands. If I could only use it to detach his wife– –”

![]() “His wife?”

“His wife?”

![]() “I am giving you some information now, in return for all

that you have given me. The lady who has passed here as Miss Stapleton is in reality his

wife.”

“I am giving you some information now, in return for all

that you have given me. The lady who has passed here as Miss Stapleton is in reality his

wife.”

![]() “Good heavens, Holmes! Are you sure of what you say? How

could he have permitted Sir Henry to fall in love with her?”

“Good heavens, Holmes! Are you sure of what you say? How

could he have permitted Sir Henry to fall in love with her?”

![]() “Sir Henry’s falling in love could do no harm to

anyone except Sir Henry. He took particular care that Sir Henry did not make love

to her, as you have yourself observed. I repeat that the lady is his wife and not his

sister.”

“Sir Henry’s falling in love could do no harm to

anyone except Sir Henry. He took particular care that Sir Henry did not make love

to her, as you have yourself observed. I repeat that the lady is his wife and not his

sister.”

![]() “But why this elaborate deception?”

“But why this elaborate deception?”

![]() “Because he foresaw that she would be very much more

useful to him in the character of a free woman.”

“Because he foresaw that she would be very much more

useful to him in the character of a free woman.”

![]() All my unspoken instincts, my vague suspicions, suddenly took

shape and centred upon the naturalist. In that impassive, colourless man, with his straw

hat and his butterfly-net, I seemed to see something terrible–a creature of infinite

patience and craft, with a smiling face and a murderous heart.

All my unspoken instincts, my vague suspicions, suddenly took

shape and centred upon the naturalist. In that impassive, colourless man, with his straw

hat and his butterfly-net, I seemed to see something terrible–a creature of infinite

patience and craft, with a smiling face and a murderous heart.

![]() “It is he, then, who is our enemy–it is he who

dogged us in London?”

“It is he, then, who is our enemy–it is he who

dogged us in London?”

![]() “So I read the riddle.”

“So I read the riddle.”

![]() “And the warning–it must have come from her!”

“And the warning–it must have come from her!”

![]() “Exactly.”

“Exactly.”

![]() The shape of some monstrous villainy, half seen, half guessed,

loomed through the darkness which had girt me so long.

The shape of some monstrous villainy, half seen, half guessed,

loomed through the darkness which had girt me so long.

![]() “But are you sure of this, Holmes? How do you know that

the woman is his wife?”

“But are you sure of this, Holmes? How do you know that

the woman is his wife?”

![]() “Because he so far forgot himself as to tell you a true

piece of autobiography upon the occasion when he first met you, and I dare say he has many

a time regretted it since. He was once a schoolmaster in the north of England. Now, there

is no one more easy to trace than a schoolmaster. There are scholastic agencies by which

one may identify any man who has been in the profession. A little investigation showed me

that a school had come to grief under atrocious circumstances, and that the man who had

owned it–the name was different–had disappeared with his wife. The descriptions

agreed. When I learned that the missing man was devoted to entomology the identification

was complete.”

“Because he so far forgot himself as to tell you a true

piece of autobiography upon the occasion when he first met you, and I dare say he has many

a time regretted it since. He was once a schoolmaster in the north of England. Now, there

is no one more easy to trace than a schoolmaster. There are scholastic agencies by which

one may identify any man who has been in the profession. A little investigation showed me

that a school had come to grief under atrocious circumstances, and that the man who had

owned it–the name was different–had disappeared with his wife. The descriptions

agreed. When I learned that the missing man was devoted to entomology the identification

was complete.”

![]() The darkness was rising, but much was still hidden by the

shadows.

The darkness was rising, but much was still hidden by the

shadows.

![]() “If this woman is in truth his wife, where does Mrs.

Laura Lyons come in?” I asked.

“If this woman is in truth his wife, where does Mrs.

Laura Lyons come in?” I asked.

![]() “That is one of the points upon which your own researches

have shed a light. Your interview with the lady has cleared the situation very much. I did

not know about a projected divorce between herself and her husband. In that case,

regarding Stapleton as an unmarried man, she counted no doubt upon becoming his

wife.”

“That is one of the points upon which your own researches

have shed a light. Your interview with the lady has cleared the situation very much. I did

not know about a projected divorce between herself and her husband. In that case,

regarding Stapleton as an unmarried man, she counted no doubt upon becoming his

wife.”

![]() “And when she is undeceived?”

“And when she is undeceived?”

![]() “Why, then we may find the lady of service. It must be

our first duty to see [743] her–both

of us–to-morrow. Don’t you think, Watson, that you are away from your charge

rather long? Your place should be at Baskerville Hall.”

“Why, then we may find the lady of service. It must be

our first duty to see [743] her–both

of us–to-morrow. Don’t you think, Watson, that you are away from your charge

rather long? Your place should be at Baskerville Hall.”

![]() The last red streaks had faded away in the west and night had

settled upon the moor. A few faint stars were gleaming in a violet sky.

The last red streaks had faded away in the west and night had

settled upon the moor. A few faint stars were gleaming in a violet sky.

![]() “One last question, Holmes,” I said as I rose.

“Surely there is no need of secrecy between you and me. What is the meaning of it

all? What is he after?”

“One last question, Holmes,” I said as I rose.

“Surely there is no need of secrecy between you and me. What is the meaning of it

all? What is he after?”

![]() Holmes’s voice sank as he answered:

Holmes’s voice sank as he answered:

![]() “It is murder, Watson–refined, cold-blooded,

deliberate murder. Do not ask me for particulars. My nets are closing upon him, even as

his are upon Sir Henry, and with your help he is already almost at my mercy. There is but

one danger which can threaten us. It is that he should strike before we are ready to do

so. Another day–two at the most–and I have my case complete, but until then

guard your charge as closely as ever a fond mother watched her ailing child. Your mission

to-day has justified itself, and yet I could almost wish that you had not left his side.

Hark!”

“It is murder, Watson–refined, cold-blooded,

deliberate murder. Do not ask me for particulars. My nets are closing upon him, even as

his are upon Sir Henry, and with your help he is already almost at my mercy. There is but

one danger which can threaten us. It is that he should strike before we are ready to do

so. Another day–two at the most–and I have my case complete, but until then

guard your charge as closely as ever a fond mother watched her ailing child. Your mission

to-day has justified itself, and yet I could almost wish that you had not left his side.

Hark!”

![]() A terrible scream–a prolonged yell of horror and anguish

burst out of the silence of the moor. That frightful cry turned the blood to ice in my

veins.

A terrible scream–a prolonged yell of horror and anguish

burst out of the silence of the moor. That frightful cry turned the blood to ice in my

veins.

![]() “Oh, my God!” I gasped. “What is it? What does

it mean?”

“Oh, my God!” I gasped. “What is it? What does

it mean?”

![]() Holmes had sprung to his feet, and I saw his dark, athletic

outline at the door of the hut, his shoulders stooping, his head thrust forward, his face

peering into the darkness.

Holmes had sprung to his feet, and I saw his dark, athletic

outline at the door of the hut, his shoulders stooping, his head thrust forward, his face

peering into the darkness.

![]() “Hush!” he whispered. “Hush!”

“Hush!” he whispered. “Hush!”

![]() The cry had been loud on account of its vehemence, but it had

pealed out from somewhere far off on the shadowy plain. Now it burst upon our ears,

nearer, louder, more urgent than before.

The cry had been loud on account of its vehemence, but it had

pealed out from somewhere far off on the shadowy plain. Now it burst upon our ears,

nearer, louder, more urgent than before.

![]() “Where is it?” Holmes whispered; and I knew from the

thrill of his voice that he, the man of iron, was shaken to the soul. “Where is it,

Watson?”

“Where is it?” Holmes whispered; and I knew from the

thrill of his voice that he, the man of iron, was shaken to the soul. “Where is it,

Watson?”

![]() “There, I think.” I pointed into the darkness.

“There, I think.” I pointed into the darkness.

![]() “No, there!”

“No, there!”

![]() Again the agonized cry swept through the silent night, louder

and much nearer than ever. And a new sound mingled with it, a deep, muttered rumble,

musical and yet menacing, rising and falling like the low, constant murmur of the sea.

Again the agonized cry swept through the silent night, louder

and much nearer than ever. And a new sound mingled with it, a deep, muttered rumble,

musical and yet menacing, rising and falling like the low, constant murmur of the sea.

![]() “The hound!” cried Holmes. “Come, Watson, come!

Great heavens, if we are too late!”

“The hound!” cried Holmes. “Come, Watson, come!

Great heavens, if we are too late!”

![]() He had started running swiftly over the moor, and I had

followed at his heels. But now from somewhere among the broken ground immediately in front

of us there came one last despairing yell, and then a dull, heavy thud. We halted and

listened. Not another sound broke the heavy silence of the windless night.

He had started running swiftly over the moor, and I had

followed at his heels. But now from somewhere among the broken ground immediately in front

of us there came one last despairing yell, and then a dull, heavy thud. We halted and

listened. Not another sound broke the heavy silence of the windless night.

![]() I saw Holmes put his hand to his forehead like a man

distracted. He stamped his feet upon the ground.

I saw Holmes put his hand to his forehead like a man

distracted. He stamped his feet upon the ground.

![]() “He has beaten us, Watson. We are too late.”

“He has beaten us, Watson. We are too late.”

![]() “No, no, surely not!”

“No, no, surely not!”

![]() “Fool that I was to hold my hand. And you, Watson, see

what comes of abandoning your charge! But, by Heaven, if the worst has happened we’ll

avenge him!”

“Fool that I was to hold my hand. And you, Watson, see

what comes of abandoning your charge! But, by Heaven, if the worst has happened we’ll

avenge him!”

![]() Blindly we ran through the gloom, blundering against boulders,

forcing our way through gorse bushes, panting up hills and rushing down slopes, heading

always in the direction whence those dreadful sounds had come. At every rise Holmes looked

eagerly round him, but the shadows were thick upon the moor, and nothing moved upon its

dreary face.

Blindly we ran through the gloom, blundering against boulders,

forcing our way through gorse bushes, panting up hills and rushing down slopes, heading

always in the direction whence those dreadful sounds had come. At every rise Holmes looked

eagerly round him, but the shadows were thick upon the moor, and nothing moved upon its

dreary face.

![]() [744] “Can

you see anything?”

[744] “Can

you see anything?”

![]() “Nothing.”

“Nothing.”

![]() “But, hark, what is that?”

“But, hark, what is that?”

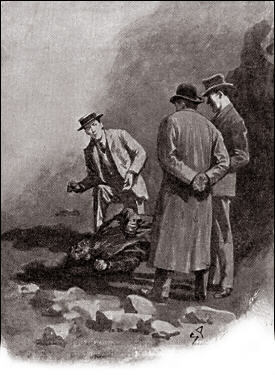

![]() A low moan had fallen upon our ears. There it was again upon

our left! On that side a ridge of rocks ended in a sheer cliff which overlooked a

stone-strewn slope. On its jagged face was spread-eagled some dark, irregular object. As

we ran towards it the vague outline hardened into a definite shape. It was a prostrate man

face downward upon the ground, the head doubled under him at a horrible angle, the

shoulders rounded and the body hunched together as if in the act of throwing a somersault.

So grotesque was the attitude that I could not for the instant realize that that moan had

been the passing of his soul. Not a whisper, not a rustle, rose now from the dark figure

over which we stooped. Holmes laid his hand upon him and held it up again with an

exclamation of horror. The gleam of the match which he struck shone upon his clotted

fingers and upon the ghastly pool which widened slowly from the crushed skull of the

victim. And it shone upon something else which turned our hearts sick and faint within

us–the body of Sir Henry Baskerville!

A low moan had fallen upon our ears. There it was again upon

our left! On that side a ridge of rocks ended in a sheer cliff which overlooked a

stone-strewn slope. On its jagged face was spread-eagled some dark, irregular object. As

we ran towards it the vague outline hardened into a definite shape. It was a prostrate man

face downward upon the ground, the head doubled under him at a horrible angle, the

shoulders rounded and the body hunched together as if in the act of throwing a somersault.

So grotesque was the attitude that I could not for the instant realize that that moan had

been the passing of his soul. Not a whisper, not a rustle, rose now from the dark figure

over which we stooped. Holmes laid his hand upon him and held it up again with an

exclamation of horror. The gleam of the match which he struck shone upon his clotted

fingers and upon the ghastly pool which widened slowly from the crushed skull of the

victim. And it shone upon something else which turned our hearts sick and faint within

us–the body of Sir Henry Baskerville!