|

|

There were only two men in the room, Sir Henry and Stapleton.

They sat with their profiles towards me on either side of the round table. Both of them

were smoking cigars, and coffee and wine were in front of them. Stapleton was talking with

animation, but the baronet looked pale and distrait. Perhaps the thought of that lonely

walk across the ill-omened moor was weighing heavily upon his mind. There were only two men in the room, Sir Henry and Stapleton.

They sat with their profiles towards me on either side of the round table. Both of them

were smoking cigars, and coffee and wine were in front of them. Stapleton was talking with

animation, but the baronet looked pale and distrait. Perhaps the thought of that lonely

walk across the ill-omened moor was weighing heavily upon his mind.

As I watched them Stapleton rose and left the room, while Sir

Henry filled his glass again and leaned back in his chair, puffing at his cigar. I heard

the creak of a door and the crisp sound of boots upon gravel. The steps passed along the

path on the other side of the wall under which I crouched. Looking over, I saw the

naturalist pause at the door of an out-house in the corner of the orchard. A key turned in

a lock, and as he passed in there was a curious scuffling noise from within. He was only a

minute or so inside, and then I heard the key turn once more and he passed me and

reentered the house. I saw him rejoin his guest, and I crept quietly back to where my

companions were waiting to tell them what I had seen. As I watched them Stapleton rose and left the room, while Sir

Henry filled his glass again and leaned back in his chair, puffing at his cigar. I heard

the creak of a door and the crisp sound of boots upon gravel. The steps passed along the

path on the other side of the wall under which I crouched. Looking over, I saw the

naturalist pause at the door of an out-house in the corner of the orchard. A key turned in

a lock, and as he passed in there was a curious scuffling noise from within. He was only a

minute or so inside, and then I heard the key turn once more and he passed me and

reentered the house. I saw him rejoin his guest, and I crept quietly back to where my

companions were waiting to tell them what I had seen.

“You say, Watson, that the lady is not there?”

Holmes asked when I had finished my report. “You say, Watson, that the lady is not there?”

Holmes asked when I had finished my report.

“No.” “No.”

“Where can she be, then, since there is no light in any

other room except the kitchen?” “Where can she be, then, since there is no light in any

other room except the kitchen?”

“I cannot think where she is.” “I cannot think where she is.”

I have said that over the great Grimpen Mire there hung a

dense, white fog. It was drifting slowly in our direction and banked itself up like a wall

on that side of us, low but thick and well defined. The moon shone on it, and it looked

like a great shimmering ice-field, with the heads of the distant tors as rocks borne upon

its surface. Holmes’s face was turned towards it, and he muttered impatiently as he

watched its sluggish drift. I have said that over the great Grimpen Mire there hung a

dense, white fog. It was drifting slowly in our direction and banked itself up like a wall

on that side of us, low but thick and well defined. The moon shone on it, and it looked

like a great shimmering ice-field, with the heads of the distant tors as rocks borne upon

its surface. Holmes’s face was turned towards it, and he muttered impatiently as he

watched its sluggish drift.

[756] “It’s

moving towards us, Watson.” [756] “It’s

moving towards us, Watson.”

“Is that serious?” “Is that serious?”

“Very serious, indeed–the one thing upon earth which

could have disarranged my plans. He can’t be very long, now. It is already ten

o’clock. Our success and even his life may depend upon his coming out before the fog

is over the path.” “Very serious, indeed–the one thing upon earth which

could have disarranged my plans. He can’t be very long, now. It is already ten

o’clock. Our success and even his life may depend upon his coming out before the fog

is over the path.”

The night was clear and fine above us. The stars shone cold

and bright, while a half-moon bathed the whole scene in a soft, uncertain light. Before us

lay the dark bulk of the house, its serrated roof and bristling chimneys hard outlined

against the silver-spangled sky. Broad bars of golden light from the lower windows

stretched across the orchard and the moor. One of them was suddenly shut off. The servants

had left the kitchen. There only remained the lamp in the dining-room where the two men,

the murderous host and the unconscious guest, still chatted over their cigars. The night was clear and fine above us. The stars shone cold

and bright, while a half-moon bathed the whole scene in a soft, uncertain light. Before us

lay the dark bulk of the house, its serrated roof and bristling chimneys hard outlined

against the silver-spangled sky. Broad bars of golden light from the lower windows

stretched across the orchard and the moor. One of them was suddenly shut off. The servants

had left the kitchen. There only remained the lamp in the dining-room where the two men,

the murderous host and the unconscious guest, still chatted over their cigars.

Every minute that white woolly plain which covered one-half of

the moor was drifting closer and closer to the house. Already the first thin wisps of it

were curling across the golden square of the lighted window. The farther wall of the

orchard was already invisible, and the trees were standing out of a swirl of white vapour.

As we watched it the fog-wreaths came crawling round both corners of the house and rolled

slowly into one dense bank, on which the upper floor and the roof floated like a strange

ship upon a shadowy sea. Holmes struck his hand passionately upon the rock in front of us

and stamped his feet in his impatience. Every minute that white woolly plain which covered one-half of

the moor was drifting closer and closer to the house. Already the first thin wisps of it

were curling across the golden square of the lighted window. The farther wall of the

orchard was already invisible, and the trees were standing out of a swirl of white vapour.

As we watched it the fog-wreaths came crawling round both corners of the house and rolled

slowly into one dense bank, on which the upper floor and the roof floated like a strange

ship upon a shadowy sea. Holmes struck his hand passionately upon the rock in front of us

and stamped his feet in his impatience.

“If he isn’t out in a quarter of an hour the path

will be covered. In half an hour we won’t be able to see our hands in front of

us.” “If he isn’t out in a quarter of an hour the path

will be covered. In half an hour we won’t be able to see our hands in front of

us.”

“Shall we move farther back upon higher ground?” “Shall we move farther back upon higher ground?”

“Yes, I think it would be as well.” “Yes, I think it would be as well.”

So as the fog-bank flowed onward we fell back before it until

we were half a mile from the house, and still that dense white sea, with the moon

silvering its upper edge, swept slowly and inexorably on. So as the fog-bank flowed onward we fell back before it until

we were half a mile from the house, and still that dense white sea, with the moon

silvering its upper edge, swept slowly and inexorably on.

“We are going too far,” said Holmes. “We dare

not take the chance of his being overtaken before he can reach us. At all costs we must

hold our ground where we are.” He dropped on his knees and clapped his ear to the

ground. “Thank God, I think that I hear him coming.” “We are going too far,” said Holmes. “We dare

not take the chance of his being overtaken before he can reach us. At all costs we must

hold our ground where we are.” He dropped on his knees and clapped his ear to the

ground. “Thank God, I think that I hear him coming.”

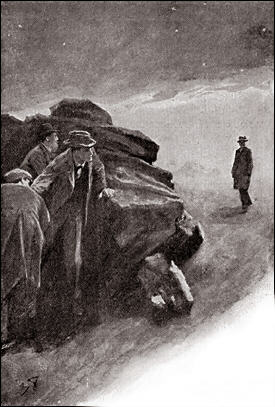

A sound of quick steps broke the silence of the moor.

Crouching among the stones we stared intently at the silver-tipped bank in front of us.

The steps grew louder, and through the fog, as through a curtain, there stepped the man

whom we were awaiting. He looked round him in surprise as he emerged into the clear,

starlit night. Then he came swiftly along the path, passed close to where we lay, and went

on up the long slope behind us. As he walked he glanced continually over either shoulder,

like a man who is ill at ease. A sound of quick steps broke the silence of the moor.

Crouching among the stones we stared intently at the silver-tipped bank in front of us.

The steps grew louder, and through the fog, as through a curtain, there stepped the man

whom we were awaiting. He looked round him in surprise as he emerged into the clear,

starlit night. Then he came swiftly along the path, passed close to where we lay, and went

on up the long slope behind us. As he walked he glanced continually over either shoulder,

like a man who is ill at ease.

“Hist!” cried Holmes, and I heard the sharp click

of a cocking pistol. “Look out! It’s coming!” “Hist!” cried Holmes, and I heard the sharp click

of a cocking pistol. “Look out! It’s coming!”

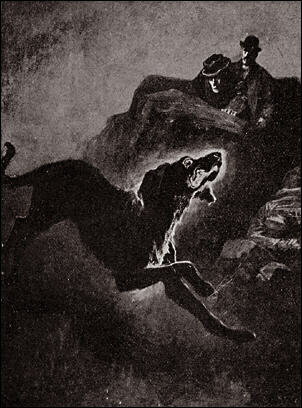

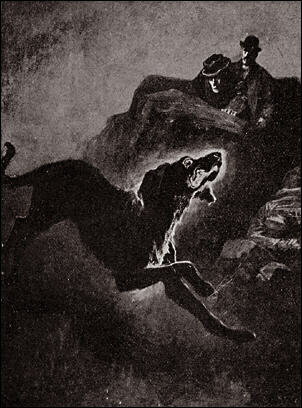

There was a thin, crisp, continuous patter from somewhere in

the heart of that crawling bank. The cloud was within fifty yards of where we lay, and we

glared at it, all three, uncertain what horror was about to break from the heart of it. I

was at Holmes’s elbow, and I glanced for an instant at his face. It was pale and

exultant, his eyes shining brightly in the moonlight. But suddenly they started forward in

a rigid, fixed stare, and his lips parted in amazement. At the same instant Lestrade gave

a yell of terror and threw himself face downward upon the ground. I sprang to my feet, my

inert hand grasping my pistol, my mind paralyzed by [757] the dreadful shape which had sprung out upon us from

the shadows of the fog. A hound it was, an enormous coal-black hound, but not such a hound

as mortal eyes have ever seen. Fire burst from its open mouth, its eyes glowed with a

smouldering glare, its muzzle and hackles and dewlap were outlined in flickering flame.

Never in the delirious dream of a disordered brain could anything more savage, more

appalling, more hellish be conceived than that dark form and savage face which broke upon

us out of the wall of fog. There was a thin, crisp, continuous patter from somewhere in

the heart of that crawling bank. The cloud was within fifty yards of where we lay, and we

glared at it, all three, uncertain what horror was about to break from the heart of it. I

was at Holmes’s elbow, and I glanced for an instant at his face. It was pale and

exultant, his eyes shining brightly in the moonlight. But suddenly they started forward in

a rigid, fixed stare, and his lips parted in amazement. At the same instant Lestrade gave

a yell of terror and threw himself face downward upon the ground. I sprang to my feet, my

inert hand grasping my pistol, my mind paralyzed by [757] the dreadful shape which had sprung out upon us from

the shadows of the fog. A hound it was, an enormous coal-black hound, but not such a hound

as mortal eyes have ever seen. Fire burst from its open mouth, its eyes glowed with a

smouldering glare, its muzzle and hackles and dewlap were outlined in flickering flame.

Never in the delirious dream of a disordered brain could anything more savage, more

appalling, more hellish be conceived than that dark form and savage face which broke upon

us out of the wall of fog.

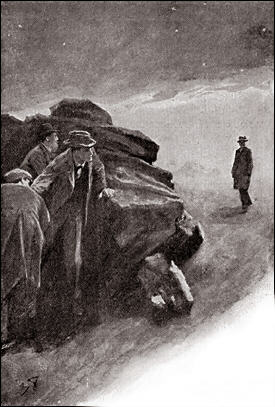

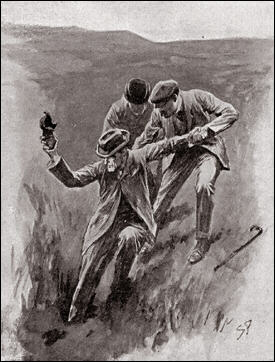

With long bounds the huge black creature was leaping down

the track, following hard upon the footsteps of our friend. So paralyzed were we by the

apparition that we allowed him to pass before we had recovered our nerve. Then Holmes and

I both fired together, and the creature gave a hideous howl, which showed that one at

least had hit him. He did not pause, however, but bounded onward. Far away on the path we

saw Sir Henry looking back, his face white in the moonlight, his hands raised in horror,

glaring helplessly at the frightful thing which was hunting him down. With long bounds the huge black creature was leaping down

the track, following hard upon the footsteps of our friend. So paralyzed were we by the

apparition that we allowed him to pass before we had recovered our nerve. Then Holmes and

I both fired together, and the creature gave a hideous howl, which showed that one at

least had hit him. He did not pause, however, but bounded onward. Far away on the path we

saw Sir Henry looking back, his face white in the moonlight, his hands raised in horror,

glaring helplessly at the frightful thing which was hunting him down.

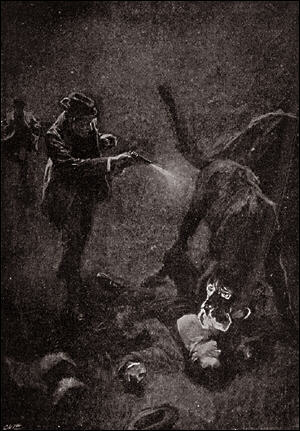

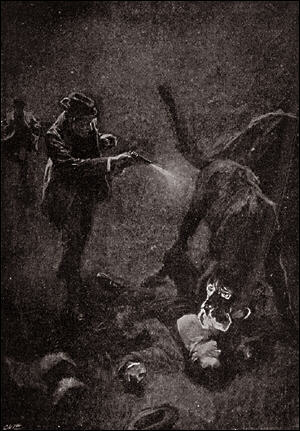

But that cry of pain from the hound had blown all our fears to

the winds. If he was vulnerable he was mortal, and if we could wound him we could kill

him. Never have I seen a man run as Holmes ran that night. I am reckoned fleet of foot,

but he outpaced me as much as I outpaced the little professional. In front of us as we

flew up the track we heard scream after scream from Sir Henry and the deep roar of the

hound. I was in time to see the beast spring upon its victim, hurl him to the ground, and

worry at his throat. But the next instant Holmes had emptied five barrels of his revolver

into the creature’s flank. With a last howl of agony and a vicious snap in the air,

it rolled upon its back, four feet pawing furiously, and then fell limp upon its side. I

stooped, panting, and pressed my pistol to the dreadful, shimmering head, but it was

useless to press the trigger. The giant hound was dead. But that cry of pain from the hound had blown all our fears to

the winds. If he was vulnerable he was mortal, and if we could wound him we could kill

him. Never have I seen a man run as Holmes ran that night. I am reckoned fleet of foot,

but he outpaced me as much as I outpaced the little professional. In front of us as we

flew up the track we heard scream after scream from Sir Henry and the deep roar of the

hound. I was in time to see the beast spring upon its victim, hurl him to the ground, and

worry at his throat. But the next instant Holmes had emptied five barrels of his revolver

into the creature’s flank. With a last howl of agony and a vicious snap in the air,

it rolled upon its back, four feet pawing furiously, and then fell limp upon its side. I

stooped, panting, and pressed my pistol to the dreadful, shimmering head, but it was

useless to press the trigger. The giant hound was dead.

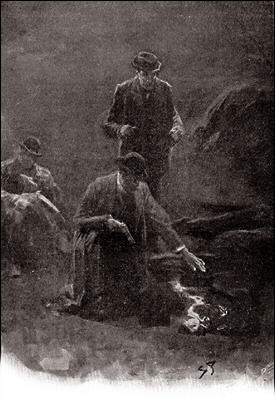

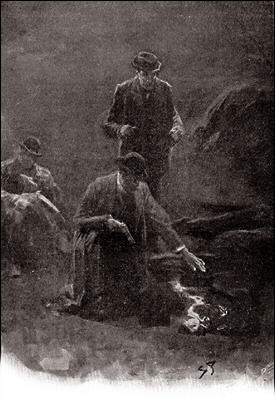

Sir Henry lay insensible where he had fallen. We tore away

his collar, and Holmes breathed a prayer of gratitude when we saw that there was no sign

of a wound and that the rescue had been in time. Already our friend’s eyelids

shivered and he made a feeble effort to move. Lestrade thrust his brandy-flask between the

baronet’s teeth, and two frightened eyes were looking up at us. Sir Henry lay insensible where he had fallen. We tore away

his collar, and Holmes breathed a prayer of gratitude when we saw that there was no sign

of a wound and that the rescue had been in time. Already our friend’s eyelids

shivered and he made a feeble effort to move. Lestrade thrust his brandy-flask between the

baronet’s teeth, and two frightened eyes were looking up at us.

“My God!” he whispered. “What was it? What, in

heaven’s name, was it?” “My God!” he whispered. “What was it? What, in

heaven’s name, was it?”

“It’s dead, whatever it is,” said Holmes.

“We’ve laid the family ghost once and forever.” “It’s dead, whatever it is,” said Holmes.

“We’ve laid the family ghost once and forever.”

In mere size and strength it was a terrible creature which was

lying stretched before us. It was not a pure bloodhound and it was not a pure mastiff; but

it appeared to be a combination of the two–gaunt, savage, and as large as a small

lioness. Even now, in the stillness of death, the huge jaws seemed to be dripping with a

bluish flame and the small, deep-set, cruel eyes were ringed with fire. I placed my hand

upon the glowing muzzle, and as I held them up my own fingers smouldered and gleamed in

the darkness. In mere size and strength it was a terrible creature which was

lying stretched before us. It was not a pure bloodhound and it was not a pure mastiff; but

it appeared to be a combination of the two–gaunt, savage, and as large as a small

lioness. Even now, in the stillness of death, the huge jaws seemed to be dripping with a

bluish flame and the small, deep-set, cruel eyes were ringed with fire. I placed my hand

upon the glowing muzzle, and as I held them up my own fingers smouldered and gleamed in

the darkness.

“Phosphorus,” I said. “Phosphorus,” I said.

“A cunning preparation of it,” said Holmes, sniffing

at the dead animal. “There is no smell which might have interfered with his power of

scent. We owe you a deep apology, Sir Henry, for having exposed you to this fright. I was

prepared for a hound, but not for such a creature as this. And the fog gave us little time

to receive him.” “A cunning preparation of it,” said Holmes, sniffing

at the dead animal. “There is no smell which might have interfered with his power of

scent. We owe you a deep apology, Sir Henry, for having exposed you to this fright. I was

prepared for a hound, but not for such a creature as this. And the fog gave us little time

to receive him.”

“You have saved my life.” “You have saved my life.”

“Having first endangered it. Are you strong enough to

stand?” “Having first endangered it. Are you strong enough to

stand?”

[758] “Give

me another mouthful of that brandy and I shall be ready for anything. So! Now, if you will

help me up. What do you propose to do?” [758] “Give

me another mouthful of that brandy and I shall be ready for anything. So! Now, if you will

help me up. What do you propose to do?”

“To leave you here. You are not fit for further

adventures to-night. If you will wait, one or other of us will go back with you to the

Hall.” “To leave you here. You are not fit for further

adventures to-night. If you will wait, one or other of us will go back with you to the

Hall.”

He tried to stagger to his feet; but he was still ghastly pale

and trembling in every limb. We helped him to a rock, where he sat shivering with his face

buried in his hands. He tried to stagger to his feet; but he was still ghastly pale

and trembling in every limb. We helped him to a rock, where he sat shivering with his face

buried in his hands.

“We must leave you now,” said Holmes. “The rest

of our work must be done, and every moment is of importance. We have our case, and now we

only want our man. “We must leave you now,” said Holmes. “The rest

of our work must be done, and every moment is of importance. We have our case, and now we

only want our man.

“It’s a thousand to one against our finding him at

the house,” he continued as we retraced our steps swiftly down the path. “Those

shots must have told him that the game was up.” “It’s a thousand to one against our finding him at

the house,” he continued as we retraced our steps swiftly down the path. “Those

shots must have told him that the game was up.”

“We were some distance off, and this fog may have

deadened them.” “We were some distance off, and this fog may have

deadened them.”

“He followed the hound to call him off–of that you

may be certain. No, no, he’s gone by this time! But we’ll search the house and

make sure.” “He followed the hound to call him off–of that you

may be certain. No, no, he’s gone by this time! But we’ll search the house and

make sure.”

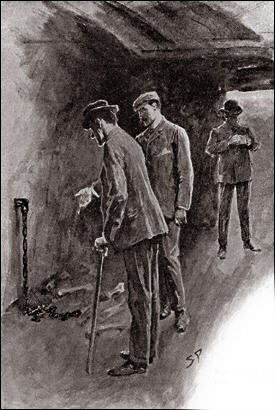

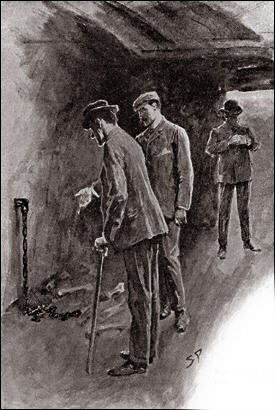

The front door was open, so we rushed in and hurried from room

to room to the amazement of a doddering old manservant, who met us in the passage. There

was no light save in the dining-room, but Holmes caught up the lamp and left no corner of

the house unexplored. No sign could we see of the man whom we were chasing. On the upper

floor, however, one of the bedroom doors was locked. The front door was open, so we rushed in and hurried from room

to room to the amazement of a doddering old manservant, who met us in the passage. There

was no light save in the dining-room, but Holmes caught up the lamp and left no corner of

the house unexplored. No sign could we see of the man whom we were chasing. On the upper

floor, however, one of the bedroom doors was locked.

“There’s someone in here,” cried Lestrade.

“I can hear a movement. Open this door!” “There’s someone in here,” cried Lestrade.

“I can hear a movement. Open this door!”

A faint moaning and rustling came from within. Holmes struck

the door just over the lock with the flat of his foot and it flew open. Pistol in hand, we

all three rushed into the room. A faint moaning and rustling came from within. Holmes struck

the door just over the lock with the flat of his foot and it flew open. Pistol in hand, we

all three rushed into the room.

But there was no sign within it of that desperate and defiant

villain whom we expected to see. Instead we were faced by an object so strange and so

unexpected that we stood for a moment staring at it in amazement. But there was no sign within it of that desperate and defiant

villain whom we expected to see. Instead we were faced by an object so strange and so

unexpected that we stood for a moment staring at it in amazement.

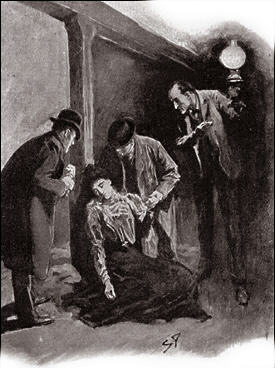

The room had been fashioned into a small museum, and the walls

were lined by a number of glass-topped cases full of that collection of butterflies and

moths the formation of which had been the relaxation of this complex and dangerous man. In

the centre of this room there was an upright beam, which had been placed at some period as

a support for the old worm-eaten baulk of timber which spanned the roof. To this post a

figure was tied, so swathed and muffled in the sheets which had been used to secure it

that one could not for the moment tell whether it was that of a man or a woman. One towel

passed round the throat and was secured at the back of the pillar. Another covered the

lower part of the face, and over it two dark eyes–eyes full of grief and shame and a

dreadful questioning–stared back at us. In a minute we had torn off the gag,

unswathed the bonds, and Mrs. Stapleton sank upon the floor in front of us. As her

beautiful head fell upon her chest I saw the clear red weal of a whiplash across her neck. The room had been fashioned into a small museum, and the walls

were lined by a number of glass-topped cases full of that collection of butterflies and

moths the formation of which had been the relaxation of this complex and dangerous man. In

the centre of this room there was an upright beam, which had been placed at some period as

a support for the old worm-eaten baulk of timber which spanned the roof. To this post a

figure was tied, so swathed and muffled in the sheets which had been used to secure it

that one could not for the moment tell whether it was that of a man or a woman. One towel

passed round the throat and was secured at the back of the pillar. Another covered the

lower part of the face, and over it two dark eyes–eyes full of grief and shame and a

dreadful questioning–stared back at us. In a minute we had torn off the gag,

unswathed the bonds, and Mrs. Stapleton sank upon the floor in front of us. As her

beautiful head fell upon her chest I saw the clear red weal of a whiplash across her neck.

“The brute!” cried Holmes. “Here, Lestrade,

your brandy-bottle! Put her in the chair! She has fainted from ill-usage and

exhaustion.” “The brute!” cried Holmes. “Here, Lestrade,

your brandy-bottle! Put her in the chair! She has fainted from ill-usage and

exhaustion.”

She opened her eyes again. She opened her eyes again.

“Is he safe?” she asked. “Has he escaped?” “Is he safe?” she asked. “Has he escaped?”

“He cannot escape us, madam.” “He cannot escape us, madam.”

“No, no, I did not mean my husband. Sir Henry? Is he

safe?” “No, no, I did not mean my husband. Sir Henry? Is he

safe?”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

[759] “And

the hound?” [759] “And

the hound?”

“It is dead.” “It is dead.”

She gave a long sigh of satisfaction. She gave a long sigh of satisfaction.

“Thank God! Thank God! Oh, this villain! See how he has

treated me!” She shot her arms out from her sleeves, and we saw with horror that they

were all mottled with bruises. “But this is nothing–nothing! It is my mind and

soul that he has tortured and defiled. I could endure it all, ill-usage, solitude, a life

of deception, everything, as long as I could still cling to the hope that I had his love,

but now I know that in this also I have been his dupe and his tool.” She broke into

passionate sobbing as she spoke. “Thank God! Thank God! Oh, this villain! See how he has

treated me!” She shot her arms out from her sleeves, and we saw with horror that they

were all mottled with bruises. “But this is nothing–nothing! It is my mind and

soul that he has tortured and defiled. I could endure it all, ill-usage, solitude, a life

of deception, everything, as long as I could still cling to the hope that I had his love,

but now I know that in this also I have been his dupe and his tool.” She broke into

passionate sobbing as she spoke.

“You bear him no good will, madam,” said Holmes.

“Tell us then where we shall find him. If you have ever aided him in evil, help us

now and so atone.” “You bear him no good will, madam,” said Holmes.

“Tell us then where we shall find him. If you have ever aided him in evil, help us

now and so atone.”

“There is but one place where he can have fled,” she

answered. “There is an old tin mine on an island in the heart of the mire. It was

there that he kept his hound and there also he had made preparations so that he might have

a refuge. That is where he would fly.” “There is but one place where he can have fled,” she

answered. “There is an old tin mine on an island in the heart of the mire. It was

there that he kept his hound and there also he had made preparations so that he might have

a refuge. That is where he would fly.”

The fog-bank lay like white wool against the window. Holmes

held the lamp towards it. The fog-bank lay like white wool against the window. Holmes

held the lamp towards it.

“See,” said he. “No one could find his way into

the Grimpen Mire to-night.” “See,” said he. “No one could find his way into

the Grimpen Mire to-night.”

She laughed and clapped her hands. Her eyes and teeth gleamed

with fierce merriment. She laughed and clapped her hands. Her eyes and teeth gleamed

with fierce merriment.

“He may find his way in, but never out,” she cried.

“How can he see the guiding wands to-night? We planted them together, he and I, to

mark the pathway through the mire. Oh, if I could only have plucked them out to-day. Then

indeed you would have had him at your mercy!” “He may find his way in, but never out,” she cried.

“How can he see the guiding wands to-night? We planted them together, he and I, to

mark the pathway through the mire. Oh, if I could only have plucked them out to-day. Then

indeed you would have had him at your mercy!”

It was evident to us that all pursuit was in vain until the

fog had lifted. Meanwhile we left Lestrade in possession of the house while Holmes and I

went back with the baronet to Baskerville Hall. The story of the Stapletons could no

longer be withheld from him, but he took the blow bravely when he learned the truth about

the woman whom he had loved. But the shock of the night’s adventures had shattered

his nerves, and before morning he lay delirious in a high fever under the care of Dr.

Mortimer. The two of them were destined to travel together round the world before Sir

Henry had become once more the hale, hearty man that he had been before he became master

of that ill-omened estate. It was evident to us that all pursuit was in vain until the

fog had lifted. Meanwhile we left Lestrade in possession of the house while Holmes and I

went back with the baronet to Baskerville Hall. The story of the Stapletons could no

longer be withheld from him, but he took the blow bravely when he learned the truth about

the woman whom he had loved. But the shock of the night’s adventures had shattered

his nerves, and before morning he lay delirious in a high fever under the care of Dr.

Mortimer. The two of them were destined to travel together round the world before Sir

Henry had become once more the hale, hearty man that he had been before he became master

of that ill-omened estate.

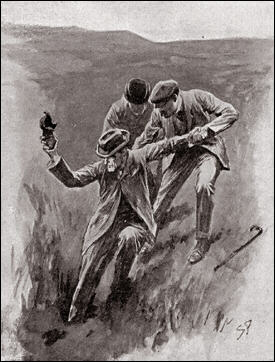

And now I come rapidly to the conclusion of this singular

narrative, in which I have tried to make the reader share those dark fears and vague

surmises which clouded our lives so long and ended in so tragic a manner. On the morning

after the death of the hound the fog had lifted and we were guided by Mrs. Stapleton to

the point where they had found a pathway through the bog. It helped us to realize the

horror of this woman’s life when we saw the eagerness and joy with which she laid us

on her husband’s track. We left her standing upon the thin peninsula of firm, peaty

soil which tapered out into the widespread bog. From the end of it a small wand planted

here and there showed where the path zigzagged from tuft to tuft of rushes among those

green-scummed pits and foul quagmires which barred the way to the stranger. Rank reeds and

lush, slimy water-plants sent an odour of decay and a heavy miasmatic vapour onto our

faces, while a false step plunged us more than once thigh-deep into the dark, quivering

mire, which [760] shook for

yards in soft undulations around our feet. Its tenacious grip plucked at our heels as we

walked, and when we sank into it it was as if some malignant hand was tugging us down into

those obscene depths, so grim and purposeful was the clutch in which it held us. Once only

we saw a trace that someone had passed that perilous way before us. From amid a tuft of

cotton-grass which bore it up out of the slime some dark thing was projecting. Holmes sank

to his waist as he stepped from the path to seize it, and had we not been there to drag

him out he could never have set his foot upon firm land again. He held an old black boot

in the air. “Meyers, Toronto,” was printed on the leather inside. And now I come rapidly to the conclusion of this singular

narrative, in which I have tried to make the reader share those dark fears and vague

surmises which clouded our lives so long and ended in so tragic a manner. On the morning

after the death of the hound the fog had lifted and we were guided by Mrs. Stapleton to

the point where they had found a pathway through the bog. It helped us to realize the

horror of this woman’s life when we saw the eagerness and joy with which she laid us

on her husband’s track. We left her standing upon the thin peninsula of firm, peaty

soil which tapered out into the widespread bog. From the end of it a small wand planted

here and there showed where the path zigzagged from tuft to tuft of rushes among those

green-scummed pits and foul quagmires which barred the way to the stranger. Rank reeds and

lush, slimy water-plants sent an odour of decay and a heavy miasmatic vapour onto our

faces, while a false step plunged us more than once thigh-deep into the dark, quivering

mire, which [760] shook for

yards in soft undulations around our feet. Its tenacious grip plucked at our heels as we

walked, and when we sank into it it was as if some malignant hand was tugging us down into

those obscene depths, so grim and purposeful was the clutch in which it held us. Once only

we saw a trace that someone had passed that perilous way before us. From amid a tuft of

cotton-grass which bore it up out of the slime some dark thing was projecting. Holmes sank

to his waist as he stepped from the path to seize it, and had we not been there to drag

him out he could never have set his foot upon firm land again. He held an old black boot

in the air. “Meyers, Toronto,” was printed on the leather inside.

“It is worth a mud bath,” said he. “It is

our friend Sir Henry’s missing boot.” “It is worth a mud bath,” said he. “It is

our friend Sir Henry’s missing boot.”

“Thrown there by Stapleton in his flight.” “Thrown there by Stapleton in his flight.”

“Exactly. He retained it in his hand after using it to

set the hound upon the track. He fled when he knew the game was up, still clutching it.

And he hurled it away at this point of his flight. We know at least that he came so far in

safety.” “Exactly. He retained it in his hand after using it to

set the hound upon the track. He fled when he knew the game was up, still clutching it.

And he hurled it away at this point of his flight. We know at least that he came so far in

safety.”

But more than that we were never destined to know, though

there was much which we might surmise. There was no chance of finding footsteps in the

mire, for the rising mud oozed swiftly in upon them, but as we at last reached firmer

ground beyond the morass we all looked eagerly for them. But no slightest sign of them

ever met our eyes. If the earth told a true story, then Stapleton never reached that

island of refuge towards which he struggled through the fog upon that last night.

Somewhere in the heart of the great Grimpen Mire, down in the foul slime of the huge

morass which had sucked him in, this cold and cruel-hearted man is forever buried. But more than that we were never destined to know, though

there was much which we might surmise. There was no chance of finding footsteps in the

mire, for the rising mud oozed swiftly in upon them, but as we at last reached firmer

ground beyond the morass we all looked eagerly for them. But no slightest sign of them

ever met our eyes. If the earth told a true story, then Stapleton never reached that

island of refuge towards which he struggled through the fog upon that last night.

Somewhere in the heart of the great Grimpen Mire, down in the foul slime of the huge

morass which had sucked him in, this cold and cruel-hearted man is forever buried.

Many traces we found of him in the bog-girt island where he

had hid his savage ally. A huge driving-wheel and a shaft half-filled with rubbish showed

the position of an abandoned mine. Beside it were the crumbling remains of the cottages of

the miners, driven away no doubt by the foul reek of the surrounding swamp. In one of

these a staple and chain with a quantity of gnawed bones showed where the animal had been

confined. A skeleton with a tangle of brown hair adhering to it lay among the d�bris. Many traces we found of him in the bog-girt island where he

had hid his savage ally. A huge driving-wheel and a shaft half-filled with rubbish showed

the position of an abandoned mine. Beside it were the crumbling remains of the cottages of

the miners, driven away no doubt by the foul reek of the surrounding swamp. In one of

these a staple and chain with a quantity of gnawed bones showed where the animal had been

confined. A skeleton with a tangle of brown hair adhering to it lay among the d�bris.

“A dog!” said Holmes. “By Jove, a

curly-haired spaniel. Poor Mortimer will never see his pet again. Well, I do not know that

this place contains any secret which we have not already fathomed. He could hide his

hound, but he could not hush its voice, and hence came those cries which even in daylight

were not pleasant to hear. On an emergency he could keep the hound in the out-house at

Merripit, but it was always a risk, and it was only on the supreme day, which he regarded

as the end of all his efforts, that he dared do it. This paste in the tin is no doubt the

luminous mixture with which the creature was daubed. It was suggested, of course, by the

story of the family hell-hound, and by the desire to frighten old Sir Charles to death. No

wonder the poor devil of a convict ran and screamed, even as our friend did, and as we

ourselves might have done, when he saw such a creature bounding through the darkness of

the moor upon his track. It was a cunning device, for, apart from the chance of driving

your victim to his death, what peasant would venture to inquire too closely into such a

creature should he get sight of it, as many have done, upon the moor? I said it in London,

Watson, and I say it again now, that never yet have we helped to hunt down a more

dangerous man than he who is lying yonder”–he swept his long arm towards the

huge mottled expanse of green-splotched bog which stretched away until it merged into the

russet slopes of the moor. “A dog!” said Holmes. “By Jove, a

curly-haired spaniel. Poor Mortimer will never see his pet again. Well, I do not know that

this place contains any secret which we have not already fathomed. He could hide his

hound, but he could not hush its voice, and hence came those cries which even in daylight

were not pleasant to hear. On an emergency he could keep the hound in the out-house at

Merripit, but it was always a risk, and it was only on the supreme day, which he regarded

as the end of all his efforts, that he dared do it. This paste in the tin is no doubt the

luminous mixture with which the creature was daubed. It was suggested, of course, by the

story of the family hell-hound, and by the desire to frighten old Sir Charles to death. No

wonder the poor devil of a convict ran and screamed, even as our friend did, and as we

ourselves might have done, when he saw such a creature bounding through the darkness of

the moor upon his track. It was a cunning device, for, apart from the chance of driving

your victim to his death, what peasant would venture to inquire too closely into such a

creature should he get sight of it, as many have done, upon the moor? I said it in London,

Watson, and I say it again now, that never yet have we helped to hunt down a more

dangerous man than he who is lying yonder”–he swept his long arm towards the

huge mottled expanse of green-splotched bog which stretched away until it merged into the

russet slopes of the moor.

|

![]() Our conversation was hampered by the presence of the driver of

the hired wagonette, so that we were forced to talk of trivial matters when our nerves

were tense with emotion and anticipation. It was a relief to me, after that unnatural

restraint, when we at last passed Frankland’s house and knew that we were drawing

near to the Hall and to the scene of action. We did not drive up to the door but got down

near the gate of the avenue. The wagonette was paid off and ordered to return to Coombe

Tracey forthwith, while we started to walk to Merripit House.

Our conversation was hampered by the presence of the driver of

the hired wagonette, so that we were forced to talk of trivial matters when our nerves

were tense with emotion and anticipation. It was a relief to me, after that unnatural

restraint, when we at last passed Frankland’s house and knew that we were drawing

near to the Hall and to the scene of action. We did not drive up to the door but got down

near the gate of the avenue. The wagonette was paid off and ordered to return to Coombe

Tracey forthwith, while we started to walk to Merripit House.![]() “Are you armed, Lestrade?”

“Are you armed, Lestrade?”![]() The little detective smiled.

The little detective smiled.![]() “As long as I have my trousers I have a hip-pocket, and

as long as I have my hip-pocket I have something in it.”

“As long as I have my trousers I have a hip-pocket, and

as long as I have my hip-pocket I have something in it.”![]() “Good! My friend and I are also ready for

emergencies.”

“Good! My friend and I are also ready for

emergencies.”![]() [755] “You’re

mighty close about this affair, Mr. Holmes. What’s the game now?”

[755] “You’re

mighty close about this affair, Mr. Holmes. What’s the game now?”![]() “A waiting game.”

“A waiting game.”![]() “My word, it does not seem a very cheerful place,”

said the detective with a shiver, glancing round him at the gloomy slopes of the hill and

at the huge lake of fog which lay over the Grimpen Mire. “I see the lights of a house

ahead of us.”

“My word, it does not seem a very cheerful place,”

said the detective with a shiver, glancing round him at the gloomy slopes of the hill and

at the huge lake of fog which lay over the Grimpen Mire. “I see the lights of a house

ahead of us.”![]() “That is Merripit House and the end of our journey. I

must request you to walk on tiptoe and not to talk above a whisper.”

“That is Merripit House and the end of our journey. I

must request you to walk on tiptoe and not to talk above a whisper.”![]() We moved cautiously along the track as if we were bound for

the house, but Holmes halted us when we were about two hundred yards from it.

We moved cautiously along the track as if we were bound for

the house, but Holmes halted us when we were about two hundred yards from it.![]() “This will do,” said he. “These rocks upon the

right make an admirable screen.”

“This will do,” said he. “These rocks upon the

right make an admirable screen.”![]() “We are to wait here?”

“We are to wait here?”![]() “Yes, we shall make our little ambush here. Get into this

hollow, Lestrade. You have been inside the house, have you not, Watson? Can you tell the

position of the rooms? What are those latticed windows at this end?”

“Yes, we shall make our little ambush here. Get into this

hollow, Lestrade. You have been inside the house, have you not, Watson? Can you tell the

position of the rooms? What are those latticed windows at this end?”![]() “I think they are the kitchen windows.”

“I think they are the kitchen windows.”![]() “And the one beyond, which shines so brightly?”

“And the one beyond, which shines so brightly?”![]() “That is certainly the dining-room.”

“That is certainly the dining-room.”![]() “The blinds are up. You know the lie of the land best.

Creep forward quietly and see what they are doing–but for heaven’s sake

don’t let them know that they are watched!”

“The blinds are up. You know the lie of the land best.

Creep forward quietly and see what they are doing–but for heaven’s sake

don’t let them know that they are watched!”![]() I tiptoed down the path and stooped behind the low wall which

surrounded the stunted orchard. Creeping in its shadow I reached a point whence I could

look straight through the uncurtained window.

I tiptoed down the path and stooped behind the low wall which

surrounded the stunted orchard. Creeping in its shadow I reached a point whence I could

look straight through the uncurtained window.