|

|

“By the way,” said the landlord in conclusion,

“you are not the only friend of Lady Frances Carfax who is inquiring after her just

now. Only a week or so ago we had a man here upon the same errand.” “By the way,” said the landlord in conclusion,

“you are not the only friend of Lady Frances Carfax who is inquiring after her just

now. Only a week or so ago we had a man here upon the same errand.”

“Did he give a name?” I asked. “Did he give a name?” I asked.

“None; but he was an Englishman, though of an unusual

type.” “None; but he was an Englishman, though of an unusual

type.”

“A savage?” said I, linking my facts after the

fashion of my illustrious friend. “A savage?” said I, linking my facts after the

fashion of my illustrious friend.

“Exactly. That describes him very well. He is a bulky,

bearded, sunburned fellow, who looks as if he would be more at home in a farmers’ inn

than in a fashionable hotel. A hard, fierce man, I should think, and one whom I should be

sorry to offend.” “Exactly. That describes him very well. He is a bulky,

bearded, sunburned fellow, who looks as if he would be more at home in a farmers’ inn

than in a fashionable hotel. A hard, fierce man, I should think, and one whom I should be

sorry to offend.”

Already the mystery began to define itself, as figures grow

clearer with the lifting of a fog. Here was this good and pious lady pursued from place to

place by a sinister and unrelenting figure. She feared him, or she would not have fled

from Lausanne. He had still followed. Sooner or later he would overtake her. Had he

already overtaken her? Was that the secret of her continued silence? Could the

good people who were her companions not screen her from his violence or his blackmail?

What horrible purpose, what deep design, lay behind this long pursuit? There was the

problem which I had to solve. Already the mystery began to define itself, as figures grow

clearer with the lifting of a fog. Here was this good and pious lady pursued from place to

place by a sinister and unrelenting figure. She feared him, or she would not have fled

from Lausanne. He had still followed. Sooner or later he would overtake her. Had he

already overtaken her? Was that the secret of her continued silence? Could the

good people who were her companions not screen her from his violence or his blackmail?

What horrible purpose, what deep design, lay behind this long pursuit? There was the

problem which I had to solve.

To Holmes I wrote showing how rapidly and surely I had got

down to the roots of the matter. In reply I had a telegram asking for a description of Dr.

Shlessinger’s left ear. Holmes’s ideas of humour are strange and occasionally

offensive, so I took no notice of his ill-timed jest–indeed, I had already reached

Montpellier in my pursuit of the maid, Marie, before his message came. To Holmes I wrote showing how rapidly and surely I had got

down to the roots of the matter. In reply I had a telegram asking for a description of Dr.

Shlessinger’s left ear. Holmes’s ideas of humour are strange and occasionally

offensive, so I took no notice of his ill-timed jest–indeed, I had already reached

Montpellier in my pursuit of the maid, Marie, before his message came.

I had no difficulty in finding the ex-servant and in learning

all that she could tell me. She was a devoted creature, who had only left her mistress

because she was sure that she was in good hands, and because her own approaching marriage

made a separation inevitable in any case. Her mistress had, as she confessed with

distress, shown some irritability of temper towards her during their stay in Baden, and

had even questioned her once as if she had suspicions of her honesty, and this had made

the parting easier than it would otherwise have been. Lady Frances had given her fifty

pounds as a wedding-present. Like me, Marie viewed with deep distrust the stranger who had

driven her mistress from Lausanne. With her own eyes she had seen him seize the

lady’s wrist with great violence on the public promenade by the lake. He was a fierce

and terrible man. She believed that it was out of dread of him that Lady Frances had

accepted the escort of the Shlessingers to London. She had never spoken to Marie about it,

but many little signs had convinced the maid that her mistress lived in a state of

continual nervous apprehension. So far she had got in her narrative, when suddenly she

sprang from her chair and her face was convulsed with surprise and fear. “See!”

she cried. “The miscreant follows still! There is the very man of whom I speak.” I had no difficulty in finding the ex-servant and in learning

all that she could tell me. She was a devoted creature, who had only left her mistress

because she was sure that she was in good hands, and because her own approaching marriage

made a separation inevitable in any case. Her mistress had, as she confessed with

distress, shown some irritability of temper towards her during their stay in Baden, and

had even questioned her once as if she had suspicions of her honesty, and this had made

the parting easier than it would otherwise have been. Lady Frances had given her fifty

pounds as a wedding-present. Like me, Marie viewed with deep distrust the stranger who had

driven her mistress from Lausanne. With her own eyes she had seen him seize the

lady’s wrist with great violence on the public promenade by the lake. He was a fierce

and terrible man. She believed that it was out of dread of him that Lady Frances had

accepted the escort of the Shlessingers to London. She had never spoken to Marie about it,

but many little signs had convinced the maid that her mistress lived in a state of

continual nervous apprehension. So far she had got in her narrative, when suddenly she

sprang from her chair and her face was convulsed with surprise and fear. “See!”

she cried. “The miscreant follows still! There is the very man of whom I speak.”

Through the open sitting-room window I saw a huge, swarthy man

with a bristling black beard walking slowly down the centre of the street and staring

eagerly at the numbers of the houses. It was clear that, like myself, he was on the track

of the maid. Acting upon the impulse of the moment, I rushed out and accosted him. Through the open sitting-room window I saw a huge, swarthy man

with a bristling black beard walking slowly down the centre of the street and staring

eagerly at the numbers of the houses. It was clear that, like myself, he was on the track

of the maid. Acting upon the impulse of the moment, I rushed out and accosted him.

“You are an Englishman,” I said. “You are an Englishman,” I said.

“What if I am?” he asked with a most villainous

scowl. “What if I am?” he asked with a most villainous

scowl.

[946] “May

I ask what your name is?” [946] “May

I ask what your name is?”

“No, you may not,” said he with decision. “No, you may not,” said he with decision.

The situation was awkward, but the most direct way is often

the best. The situation was awkward, but the most direct way is often

the best.

“Where is the Lady Frances Carfax?” I asked. “Where is the Lady Frances Carfax?” I asked.

He stared at me in amazement. He stared at me in amazement.

“What have you done with her? Why have you pursued her? I

insist upon an answer!” said I. “What have you done with her? Why have you pursued her? I

insist upon an answer!” said I.

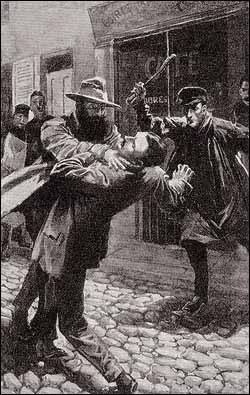

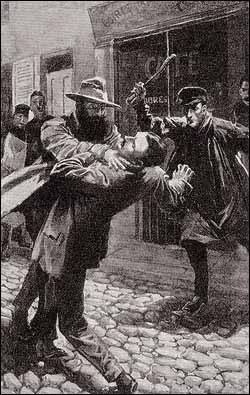

The fellow gave a bellow of anger and sprang upon me like a

tiger. I have held my own in many a struggle, but the man had a grip of iron and the fury

of a fiend. His hand was on my throat and my senses were nearly gone before an unshaven

French ouvrier in a blue blouse darted out from a cabaret opposite, with

a cudgel in his hand, and struck my assailant a sharp crack over the forearm, which made

him leave go his hold. He stood for an instant fuming with rage and uncertain whether he

should not renew his attack. Then, with a snarl of anger, he left me and entered the

cottage from which I had just come. I turned to thank my preserver, who stood beside me in

the roadway. The fellow gave a bellow of anger and sprang upon me like a

tiger. I have held my own in many a struggle, but the man had a grip of iron and the fury

of a fiend. His hand was on my throat and my senses were nearly gone before an unshaven

French ouvrier in a blue blouse darted out from a cabaret opposite, with

a cudgel in his hand, and struck my assailant a sharp crack over the forearm, which made

him leave go his hold. He stood for an instant fuming with rage and uncertain whether he

should not renew his attack. Then, with a snarl of anger, he left me and entered the

cottage from which I had just come. I turned to thank my preserver, who stood beside me in

the roadway.

“Well, Watson,” said he, “a very pretty hash

you have made of it! I rather think you had better come back with me to London by the

night express.” “Well, Watson,” said he, “a very pretty hash

you have made of it! I rather think you had better come back with me to London by the

night express.”

An hour afterwards, Sherlock Holmes, in his usual garb and

style, was seated in my private room at the hotel. His explanation of his sudden and

opportune appearance was simplicity itself, for, finding that he could get away from

London, he determined to head me off at the next obvious point of my travels. In the

disguise of a workingman he had sat in the cabaret waiting for my appearance. An hour afterwards, Sherlock Holmes, in his usual garb and

style, was seated in my private room at the hotel. His explanation of his sudden and

opportune appearance was simplicity itself, for, finding that he could get away from

London, he determined to head me off at the next obvious point of my travels. In the

disguise of a workingman he had sat in the cabaret waiting for my appearance.

“And a singularly consistent investigation you have made,

my dear Watson,” said he. “I cannot at the moment recall any possible blunder

which you have omitted. The total effect of your proceeding has been to give the alarm

everywhere and yet to discover nothing.” “And a singularly consistent investigation you have made,

my dear Watson,” said he. “I cannot at the moment recall any possible blunder

which you have omitted. The total effect of your proceeding has been to give the alarm

everywhere and yet to discover nothing.”

“Perhaps you would have done no better,” I answered

bitterly. “Perhaps you would have done no better,” I answered

bitterly.

“There is no ‘perhaps’ about it. I have

done better. Here is the Hon. Philip Green, who is a fellow-lodger with you in this hotel,

and we may find him the starting-point for a more successful investigation.” “There is no ‘perhaps’ about it. I have

done better. Here is the Hon. Philip Green, who is a fellow-lodger with you in this hotel,

and we may find him the starting-point for a more successful investigation.”

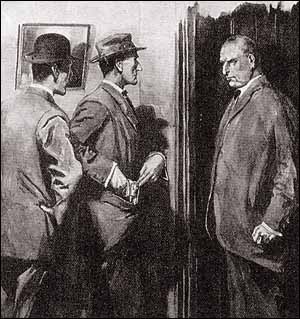

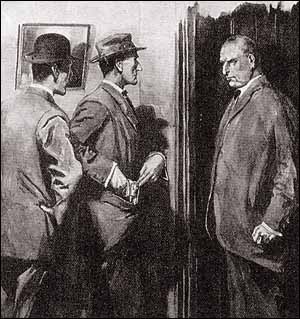

A card had come up on a salver, and it was followed by the

same bearded ruffian who had attacked me in the street. He started when he saw me. A card had come up on a salver, and it was followed by the

same bearded ruffian who had attacked me in the street. He started when he saw me.

“What is this, Mr. Holmes?” he asked. “I had

your note and I have come. But what has this man to do with the matter?” “What is this, Mr. Holmes?” he asked. “I had

your note and I have come. But what has this man to do with the matter?”

“This is my old friend and associate, Dr. Watson, who is

helping us in this affair.” “This is my old friend and associate, Dr. Watson, who is

helping us in this affair.”

The stranger held out a huge, sunburned hand, with a few words

of apology. The stranger held out a huge, sunburned hand, with a few words

of apology.

“I hope I didn’t harm you. When you accused me of

hurting her I lost my grip of myself. Indeed, I’m not responsible in these days. My

nerves are like live wires. But this situation is beyond me. What I want to know, in the

first place, Mr. Holmes, is, how in the world you came to hear of my existence at

all.” “I hope I didn’t harm you. When you accused me of

hurting her I lost my grip of myself. Indeed, I’m not responsible in these days. My

nerves are like live wires. But this situation is beyond me. What I want to know, in the

first place, Mr. Holmes, is, how in the world you came to hear of my existence at

all.”

“I am in touch with Miss Dobney, Lady Frances’s

governess.” “I am in touch with Miss Dobney, Lady Frances’s

governess.”

“Old Susan Dobney with the mob cap! I remember her

well.” “Old Susan Dobney with the mob cap! I remember her

well.”

“And she remembers you. It was in the days

before–before you found it better to go to South Africa.” “And she remembers you. It was in the days

before–before you found it better to go to South Africa.”

“Ah, I see you know my whole story. I need hide nothing

from you. I swear to you, Mr. Holmes, that there never was in this world a man who loved a

woman with a more wholehearted love than I had for Frances. I was a wild youngster, I [947] know–not worse than

others of my class. But her mind was pure as snow. She could not bear a shadow of

coarseness. So, when she came to hear of things that I had done, she would have no more to

say to me. And yet she loved me–that is the wonder of it!–loved me well enough

to remain single all her sainted days just for my sake alone. When the years had passed

and I had made my money at Barberton I thought perhaps I could seek her out and soften

her. I had heard that she was still unmarried. I found her at Lausanne and tried all I

knew. She weakened, I think, but her will was strong, and when next I called she had left

the town. I traced her to Baden, and then after a time heard that her maid was here.

I’m a rough fellow, fresh from a rough life, and when Dr. Watson spoke to me as he

did I lost hold of myself for a moment. But for God’s sake tell me what has become of

the Lady Frances.” “Ah, I see you know my whole story. I need hide nothing

from you. I swear to you, Mr. Holmes, that there never was in this world a man who loved a

woman with a more wholehearted love than I had for Frances. I was a wild youngster, I [947] know–not worse than

others of my class. But her mind was pure as snow. She could not bear a shadow of

coarseness. So, when she came to hear of things that I had done, she would have no more to

say to me. And yet she loved me–that is the wonder of it!–loved me well enough

to remain single all her sainted days just for my sake alone. When the years had passed

and I had made my money at Barberton I thought perhaps I could seek her out and soften

her. I had heard that she was still unmarried. I found her at Lausanne and tried all I

knew. She weakened, I think, but her will was strong, and when next I called she had left

the town. I traced her to Baden, and then after a time heard that her maid was here.

I’m a rough fellow, fresh from a rough life, and when Dr. Watson spoke to me as he

did I lost hold of myself for a moment. But for God’s sake tell me what has become of

the Lady Frances.”

“That is for us to find out,” said Sherlock Holmes

with peculiar gravity. “What is your London address, Mr. Green?” “That is for us to find out,” said Sherlock Holmes

with peculiar gravity. “What is your London address, Mr. Green?”

“The Langham Hotel will find me.” “The Langham Hotel will find me.”

“Then may I recommend that you return there and be on

hand in case I should want you? I have no desire to encourage false hopes, but you may

rest assured that all that can be done will be done for the safety of Lady Frances. I can

say no more for the instant. I will leave you this card so that you may be able to keep in

touch with us. Now, Watson, if you will pack your bag I will cable to Mrs. Hudson to make

one of her best efforts for two hungry travellers at 7:30 to-morrow.” “Then may I recommend that you return there and be on

hand in case I should want you? I have no desire to encourage false hopes, but you may

rest assured that all that can be done will be done for the safety of Lady Frances. I can

say no more for the instant. I will leave you this card so that you may be able to keep in

touch with us. Now, Watson, if you will pack your bag I will cable to Mrs. Hudson to make

one of her best efforts for two hungry travellers at 7:30 to-morrow.”

A telegram was awaiting us when we reached our Baker Street

rooms, which Holmes read with an exclamation of interest and threw across to me.

“Jagged or torn,” was the message, and the place of origin, Baden. A telegram was awaiting us when we reached our Baker Street

rooms, which Holmes read with an exclamation of interest and threw across to me.

“Jagged or torn,” was the message, and the place of origin, Baden.

“What is this?” I asked. “What is this?” I asked.

“It is everything,” Holmes answered. “You may

remember my seemingly irrelevant question as to this clerical gentleman’s left ear.

You did not answer it.” “It is everything,” Holmes answered. “You may

remember my seemingly irrelevant question as to this clerical gentleman’s left ear.

You did not answer it.”

“I had left Baden and could not inquire.” “I had left Baden and could not inquire.”

“Exactly. For this reason I sent a duplicate to the

manager of the Englischer Hof, whose answer lies here.” “Exactly. For this reason I sent a duplicate to the

manager of the Englischer Hof, whose answer lies here.”

“What does it show?” “What does it show?”

“It shows, my dear Watson, that we are dealing with an

exceptionally astute and dangerous man. The Rev. Dr. Shlessinger, missionary from South

America, is none other than Holy Peters, one of the most unscrupulous rascals that

Australia has ever evolved–and for a young country it has turned out some very

finished types. His particular specialty is the beguiling of lonely ladies by playing upon

their religious feelings, and his so-called wife, an Englishwoman named Fraser, is a

worthy helpmate. The nature of his tactics suggested his identity to me, and this physical

peculiarity–he was badly bitten in a saloon-fight at Adelaide in

’89–confirmed my suspicion. This poor lady is in the hands of a most infernal

couple, who will stick at nothing, Watson. That she is already dead is a very likely

supposition. If not, she is undoubtedly in some sort of confinement and unable to write to

Miss Dobney or her other friends. It is always possible that she never reached London, or

that she has passed through it, but the former is improbable, as, with their system of

registration, it is not easy for foreigners to play tricks with the Continental police;

and the latter is also unlikely, as these rogues could not hope to find any other place

where it would be as easy to keep a person under restraint. All my instincts tell me that

she is in London, but as we have at present [948]

no possible means of telling where, we can only take the obvious steps, eat

our dinner, and possess our souls in patience. Later in the evening I will stroll down and

have a word with friend Lestrade at Scotland Yard.” “It shows, my dear Watson, that we are dealing with an

exceptionally astute and dangerous man. The Rev. Dr. Shlessinger, missionary from South

America, is none other than Holy Peters, one of the most unscrupulous rascals that

Australia has ever evolved–and for a young country it has turned out some very

finished types. His particular specialty is the beguiling of lonely ladies by playing upon

their religious feelings, and his so-called wife, an Englishwoman named Fraser, is a

worthy helpmate. The nature of his tactics suggested his identity to me, and this physical

peculiarity–he was badly bitten in a saloon-fight at Adelaide in

’89–confirmed my suspicion. This poor lady is in the hands of a most infernal

couple, who will stick at nothing, Watson. That she is already dead is a very likely

supposition. If not, she is undoubtedly in some sort of confinement and unable to write to

Miss Dobney or her other friends. It is always possible that she never reached London, or

that she has passed through it, but the former is improbable, as, with their system of

registration, it is not easy for foreigners to play tricks with the Continental police;

and the latter is also unlikely, as these rogues could not hope to find any other place

where it would be as easy to keep a person under restraint. All my instincts tell me that

she is in London, but as we have at present [948]

no possible means of telling where, we can only take the obvious steps, eat

our dinner, and possess our souls in patience. Later in the evening I will stroll down and

have a word with friend Lestrade at Scotland Yard.”

But neither the official police nor Holmes’s own small

but very efficient organization sufficed to clear away the mystery. Amid the crowded

millions of London the three persons we sought were as completely obliterated as if they

had never lived. Advertisements were tried, and failed. Clues were followed, and led to

nothing. Every criminal resort which Shlessinger might frequent was drawn in vain. His old

associates were watched, but they kept clear of him. And then suddenly, after a week of

helpless suspense there came a flash of light. A silver-and-brilliant pendant of old

Spanish design had been pawned at Bovington’s, in Westminster Road. The pawner was a

large, clean-shaven man of clerical appearance. His name and address were demonstrably

false. The ear had escaped notice, but the description was surely that of Shlessinger. But neither the official police nor Holmes’s own small

but very efficient organization sufficed to clear away the mystery. Amid the crowded

millions of London the three persons we sought were as completely obliterated as if they

had never lived. Advertisements were tried, and failed. Clues were followed, and led to

nothing. Every criminal resort which Shlessinger might frequent was drawn in vain. His old

associates were watched, but they kept clear of him. And then suddenly, after a week of

helpless suspense there came a flash of light. A silver-and-brilliant pendant of old

Spanish design had been pawned at Bovington’s, in Westminster Road. The pawner was a

large, clean-shaven man of clerical appearance. His name and address were demonstrably

false. The ear had escaped notice, but the description was surely that of Shlessinger.

Three times had our bearded friend from the Langham called for

news–the third time within an hour of this fresh development. His clothes were

getting looser on his great body. He seemed to be wilting away in his anxiety. “If

you will only give me something to do!” was his constant wail. At last Holmes could

oblige him. Three times had our bearded friend from the Langham called for

news–the third time within an hour of this fresh development. His clothes were

getting looser on his great body. He seemed to be wilting away in his anxiety. “If

you will only give me something to do!” was his constant wail. At last Holmes could

oblige him.

“He has begun to pawn the jewels. We should get him

now.” “He has begun to pawn the jewels. We should get him

now.”

“But does this mean that any harm has befallen the Lady

Frances?” “But does this mean that any harm has befallen the Lady

Frances?”

Holmes shook his head very gravely. Holmes shook his head very gravely.

“Supposing that they have held her prisoner up to now, it

is clear that they cannot let her loose without their own destruction. We must prepare for

the worst.” “Supposing that they have held her prisoner up to now, it

is clear that they cannot let her loose without their own destruction. We must prepare for

the worst.”

“What can I do?” “What can I do?”

“These people do not know you by sight?” “These people do not know you by sight?”

“No.” “No.”

“It is possible that he will go to some other pawnbroker

in the future. In that case, we must begin again. On the other hand, he has had a fair

price and no questions asked, so if he is in need of ready-money he will probably come

back to Bovington’s. I will give you a note to them, and they will let you wait in

the shop. If the fellow comes you will follow him home. But no indiscretion, and, above

all, no violence. I put you on your honour that you will take no step without my knowledge

and consent.” “It is possible that he will go to some other pawnbroker

in the future. In that case, we must begin again. On the other hand, he has had a fair

price and no questions asked, so if he is in need of ready-money he will probably come

back to Bovington’s. I will give you a note to them, and they will let you wait in

the shop. If the fellow comes you will follow him home. But no indiscretion, and, above

all, no violence. I put you on your honour that you will take no step without my knowledge

and consent.”

For two days the Hon. Philip Green (he was, I may mention, the

son of the famous admiral of that name who commanded the Sea of Azof fleet in the Crimean

War) brought us no news. On the evening of the third he rushed into our sitting-room,

pale, trembling, with every muscle of his powerful frame quivering with excitement. For two days the Hon. Philip Green (he was, I may mention, the

son of the famous admiral of that name who commanded the Sea of Azof fleet in the Crimean

War) brought us no news. On the evening of the third he rushed into our sitting-room,

pale, trembling, with every muscle of his powerful frame quivering with excitement.

“We have him! We have him!” he cried. “We have him! We have him!” he cried.

He was incoherent in his agitation. Holmes soothed him with a

few words and thrust him into an armchair. He was incoherent in his agitation. Holmes soothed him with a

few words and thrust him into an armchair.

“Come, now, give us the order of events,” said he. “Come, now, give us the order of events,” said he.

“She came only an hour ago. It was the wife, this time,

but the pendant she brought was the fellow of the other. She is a tall, pale woman, with

ferret eyes.” “She came only an hour ago. It was the wife, this time,

but the pendant she brought was the fellow of the other. She is a tall, pale woman, with

ferret eyes.”

“That is the lady,” said Holmes. “That is the lady,” said Holmes.

“She left the office and I followed her. She walked up

the Kennington Road, [949] and

I kept behind her. Presently she went into a shop. Mr. Holmes, it was an

undertaker’s.” “She left the office and I followed her. She walked up

the Kennington Road, [949] and

I kept behind her. Presently she went into a shop. Mr. Holmes, it was an

undertaker’s.”

My companion started. “Well?” he asked in that

vibrant voice which told of the fiery soul behind the cold gray face. My companion started. “Well?” he asked in that

vibrant voice which told of the fiery soul behind the cold gray face.

“She was talking to the woman behind the counter. I

entered as well. ‘It is late,’ I heard her say, or words to that effect. The

woman was excusing herself. ‘It should be there before now,’ she answered.

‘It took longer, being out of the ordinary.’ They both stopped and looked at me,

so I asked some question and then left the shop.” “She was talking to the woman behind the counter. I

entered as well. ‘It is late,’ I heard her say, or words to that effect. The

woman was excusing herself. ‘It should be there before now,’ she answered.

‘It took longer, being out of the ordinary.’ They both stopped and looked at me,

so I asked some question and then left the shop.”

“You did excellently well. What happened next?” “You did excellently well. What happened next?”

“The woman came out, but I had hid myself in a doorway.

Her suspicions had been aroused, I think, for she looked round her. Then she called a cab

and got in. I was lucky enough to get another and so to follow her. She got down at last

at No. 36, Poultney Square, Brixton. I drove past, left my cab at the corner of the

square, and watched the house.” “The woman came out, but I had hid myself in a doorway.

Her suspicions had been aroused, I think, for she looked round her. Then she called a cab

and got in. I was lucky enough to get another and so to follow her. She got down at last

at No. 36, Poultney Square, Brixton. I drove past, left my cab at the corner of the

square, and watched the house.”

“Did you see anyone?” “Did you see anyone?”

“The windows were all in darkness save one on the lower

floor. The blind was down, and I could not see in. I was standing there, wondering what I

should do next, when a covered van drove up with two men in it. They descended, took

something out of the van, and carried it up the steps to the hall door. Mr. Holmes, it was

a coffin.” “The windows were all in darkness save one on the lower

floor. The blind was down, and I could not see in. I was standing there, wondering what I

should do next, when a covered van drove up with two men in it. They descended, took

something out of the van, and carried it up the steps to the hall door. Mr. Holmes, it was

a coffin.”

“Ah!” “Ah!”

“For an instant I was on the point of rushing in. The

door had been opened to admit the men and their burden. It was the woman who had opened

it. But as I stood there she caught a glimpse of me, and I think that she recognized me. I

saw her start, and she hastily closed the door. I remembered my promise to you, and here I

am.” “For an instant I was on the point of rushing in. The

door had been opened to admit the men and their burden. It was the woman who had opened

it. But as I stood there she caught a glimpse of me, and I think that she recognized me. I

saw her start, and she hastily closed the door. I remembered my promise to you, and here I

am.”

“You have done excellent work,” said Holmes

scribbling a few words upon a half-sheet of paper. “We can do nothing legal without a

warrant, and you can serve the cause best by taking this note down to the authorities and

getting one. There may be some difficulty, but I should think that the sale of the

jewellery should be sufficient. Lestrade will see to all details.” “You have done excellent work,” said Holmes

scribbling a few words upon a half-sheet of paper. “We can do nothing legal without a

warrant, and you can serve the cause best by taking this note down to the authorities and

getting one. There may be some difficulty, but I should think that the sale of the

jewellery should be sufficient. Lestrade will see to all details.”

“But they may murder her in the meanwhile. What could the

coffin mean, and for whom could it be but for her?” “But they may murder her in the meanwhile. What could the

coffin mean, and for whom could it be but for her?”

“We will do all that can be done, Mr. Green. Not a moment

will be lost. Leave it in our hands. Now, Watson,” he added as our client hurried

away, “he will set the regular forces on the move. We are, as usual, the irregulars,

and we must take our own line of action. The situation strikes me as so desperate that the

most extreme measures are justified. Not a moment is to be lost in getting to Poultney

Square. “We will do all that can be done, Mr. Green. Not a moment

will be lost. Leave it in our hands. Now, Watson,” he added as our client hurried

away, “he will set the regular forces on the move. We are, as usual, the irregulars,

and we must take our own line of action. The situation strikes me as so desperate that the

most extreme measures are justified. Not a moment is to be lost in getting to Poultney

Square.

“Let us try to reconstruct the situation,” said he

as we drove swiftly past the Houses of Parliament and over Westminster Bridge. “These

villains have coaxed this unhappy lady to London, after first alienating her from her

faithful maid. If she has written any letters they have been intercepted. Through some

confederate they have engaged a furnished house. Once inside it, they have made her a

prisoner, and they have become possessed of the valuable jewellery which has been their

object from the first. Already they have begun to sell part of it, which seems safe enough

to them, since they have no reason to think that anyone is interested in the lady’s

fate. When she is released she will, of course, denounce them. [950] Therefore, she must not be released. But they cannot

keep her under lock and key forever. So murder is their only solution.” “Let us try to reconstruct the situation,” said he

as we drove swiftly past the Houses of Parliament and over Westminster Bridge. “These

villains have coaxed this unhappy lady to London, after first alienating her from her

faithful maid. If she has written any letters they have been intercepted. Through some

confederate they have engaged a furnished house. Once inside it, they have made her a

prisoner, and they have become possessed of the valuable jewellery which has been their

object from the first. Already they have begun to sell part of it, which seems safe enough

to them, since they have no reason to think that anyone is interested in the lady’s

fate. When she is released she will, of course, denounce them. [950] Therefore, she must not be released. But they cannot

keep her under lock and key forever. So murder is their only solution.”

“That seems very clear.” “That seems very clear.”

“Now we will take another line of reasoning. When you

follow two separate chains of thought, Watson, you will find some point of intersection

which should approximate to the truth. We will start now, not from the lady but from the

coffin and argue backward. That incident proves, I fear, beyond all doubt that the lady is

dead. It points also to an orthodox burial with proper accompaniment of medical

certificate and official sanction. Had the lady been obviously murdered, they would have

buried her in a hole in the back garden. But here all is open and regular. What does that

mean? Surely that they have done her to death in some way which has deceived the doctor

and simulated a natural end–poisoning, perhaps. And yet how strange that they should

ever let a doctor approach her unless he were a confederate, which is hardly a credible

proposition.” “Now we will take another line of reasoning. When you

follow two separate chains of thought, Watson, you will find some point of intersection

which should approximate to the truth. We will start now, not from the lady but from the

coffin and argue backward. That incident proves, I fear, beyond all doubt that the lady is

dead. It points also to an orthodox burial with proper accompaniment of medical

certificate and official sanction. Had the lady been obviously murdered, they would have

buried her in a hole in the back garden. But here all is open and regular. What does that

mean? Surely that they have done her to death in some way which has deceived the doctor

and simulated a natural end–poisoning, perhaps. And yet how strange that they should

ever let a doctor approach her unless he were a confederate, which is hardly a credible

proposition.”

“Could they have forged a medical certificate?” “Could they have forged a medical certificate?”

“Dangerous, Watson, very dangerous. No, I hardly see them

doing that. Pull up, cabby! This is evidently the undertaker’s, for we have just

passed the pawnbroker’s. Would you go in, Watson? Your appearance inspires

confidence. Ask what hour the Poultney Square funeral takes place to-morrow.” “Dangerous, Watson, very dangerous. No, I hardly see them

doing that. Pull up, cabby! This is evidently the undertaker’s, for we have just

passed the pawnbroker’s. Would you go in, Watson? Your appearance inspires

confidence. Ask what hour the Poultney Square funeral takes place to-morrow.”

The woman in the shop answered me without hesitation that it

was to be at eight o’clock in the morning. “You see, Watson, no mystery;

everything above-board! In some way the legal forms have undoubtedly been complied with,

and they think that they have little to fear. Well, there’s nothing for it now but a

direct frontal attack. Are you armed?” The woman in the shop answered me without hesitation that it

was to be at eight o’clock in the morning. “You see, Watson, no mystery;

everything above-board! In some way the legal forms have undoubtedly been complied with,

and they think that they have little to fear. Well, there’s nothing for it now but a

direct frontal attack. Are you armed?”

“My stick!” “My stick!”

“Well, well, we shall be strong enough. ‘Thrice is

he armed who hath his quarrel just.’ We simply can’t afford to wait for the

police or to keep within the four corners of the law. You can drive off, cabby. Now,

Watson, we’ll just take our luck together, as we have occasionally done in the

past.” “Well, well, we shall be strong enough. ‘Thrice is

he armed who hath his quarrel just.’ We simply can’t afford to wait for the

police or to keep within the four corners of the law. You can drive off, cabby. Now,

Watson, we’ll just take our luck together, as we have occasionally done in the

past.”

He had rung loudly at the door of a great dark house in the

centre of Poultney Square. It was opened immediately, and the figure of a tall woman was

outlined against the dim-lit hall. He had rung loudly at the door of a great dark house in the

centre of Poultney Square. It was opened immediately, and the figure of a tall woman was

outlined against the dim-lit hall.

“Well, what do you want?” she asked sharply, peering

at us through the darkness. “Well, what do you want?” she asked sharply, peering

at us through the darkness.

“I want to speak to Dr. Shlessinger,” said Holmes. “I want to speak to Dr. Shlessinger,” said Holmes.

“There is no such person here,” she answered, and

tried to close the door, but Holmes had jammed it with his foot. “There is no such person here,” she answered, and

tried to close the door, but Holmes had jammed it with his foot.

“Well, I want to see the man who lives here, whatever he

may call himself,” said Holmes firmly. “Well, I want to see the man who lives here, whatever he

may call himself,” said Holmes firmly.

She hesitated. Then she threw open the door. “Well, come

in!” said she. “My husband is not afraid to face any man in the world.” She

closed the door behind us and showed us into a sitting-room on the right side of the hall,

turning up the gas as she left us. “Mr. Peters will be with you in an instant,”

she said. She hesitated. Then she threw open the door. “Well, come

in!” said she. “My husband is not afraid to face any man in the world.” She

closed the door behind us and showed us into a sitting-room on the right side of the hall,

turning up the gas as she left us. “Mr. Peters will be with you in an instant,”

she said.

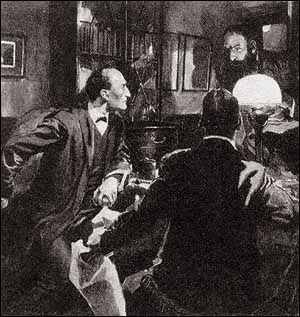

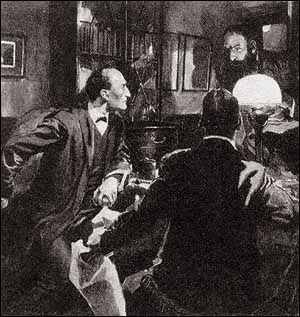

Her words were literally true, for we had hardly time to look

around the dusty and moth-eaten apartment in which we found ourselves before the door

opened and a big, clean-shaven bald-headed man stepped lightly into the room. He had a

large red face, with pendulous cheeks, and a general air of superficial benevolence which

was marred by a cruel, vicious mouth. Her words were literally true, for we had hardly time to look

around the dusty and moth-eaten apartment in which we found ourselves before the door

opened and a big, clean-shaven bald-headed man stepped lightly into the room. He had a

large red face, with pendulous cheeks, and a general air of superficial benevolence which

was marred by a cruel, vicious mouth.

“There is surely some mistake here, gentlemen,” he

said in an unctuous, [951] make-everything-easy

voice. “I fancy that you have been misdirected. Possibly if you tried farther down

the street– –” “There is surely some mistake here, gentlemen,” he

said in an unctuous, [951] make-everything-easy

voice. “I fancy that you have been misdirected. Possibly if you tried farther down

the street– –”

“That will do; we have no time to waste,” said my

companion firmly. “You are Henry Peters, of Adelaide, late the Rev. Dr. Shlessinger,

of Baden and South America. I am as sure of that as that my own name is Sherlock

Holmes.” “That will do; we have no time to waste,” said my

companion firmly. “You are Henry Peters, of Adelaide, late the Rev. Dr. Shlessinger,

of Baden and South America. I am as sure of that as that my own name is Sherlock

Holmes.”

Peters, as I will now call him, started and stared hard at his

formidable pursuer. “I guess your name does not frighten me, Mr. Holmes,” said

he coolly. “When a man’s conscience is easy you can’t rattle him. What is

your business in my house?” Peters, as I will now call him, started and stared hard at his

formidable pursuer. “I guess your name does not frighten me, Mr. Holmes,” said

he coolly. “When a man’s conscience is easy you can’t rattle him. What is

your business in my house?”

“I want to know what you have done with the Lady Frances

Carfax, whom you brought away with you from Baden.” “I want to know what you have done with the Lady Frances

Carfax, whom you brought away with you from Baden.”

“I’d be very glad if you could tell me where that

lady may be,” Peters answered coolly. “I’ve a bill against her for nearly a

hundred pounds, and nothing to show for it but a couple of trumpery pendants that the

dealer would hardly look at. She attached herself to Mrs. Peters and me at Baden–it

is a fact that I was using another name at the time–and she stuck on to us until we

came to London. I paid her bill and her ticket. Once in London, she gave us the slip, and,

as I say, left these out-of-date jewels to pay her bills. You find her, Mr. Holmes, and

I’m your debtor.” “I’d be very glad if you could tell me where that

lady may be,” Peters answered coolly. “I’ve a bill against her for nearly a

hundred pounds, and nothing to show for it but a couple of trumpery pendants that the

dealer would hardly look at. She attached herself to Mrs. Peters and me at Baden–it

is a fact that I was using another name at the time–and she stuck on to us until we

came to London. I paid her bill and her ticket. Once in London, she gave us the slip, and,

as I say, left these out-of-date jewels to pay her bills. You find her, Mr. Holmes, and

I’m your debtor.”

“I mean to find her,” said Sherlock Holmes.

“I’m going through this house till I do find her.” “I mean to find her,” said Sherlock Holmes.

“I’m going through this house till I do find her.”

“Where is your warrant?” “Where is your warrant?”

Holmes half drew a revolver from his pocket. “This

will have to serve till a better one comes.” Holmes half drew a revolver from his pocket. “This

will have to serve till a better one comes.”

“Why, you are a common burglar.” “Why, you are a common burglar.”

“So you might describe me,” said Holmes cheerfully.

“My companion is also a dangerous ruffian. And together we are going through your

house.” “So you might describe me,” said Holmes cheerfully.

“My companion is also a dangerous ruffian. And together we are going through your

house.”

Our opponent opened the door. Our opponent opened the door.

“Fetch a policeman, Annie!” said he. There was a

whisk of feminine skirts down the passage, and the hall door was opened and shut. “Fetch a policeman, Annie!” said he. There was a

whisk of feminine skirts down the passage, and the hall door was opened and shut.

“Our time is limited, Watson,” said Holmes. “If

you try to stop us, Peters, you will most certainly get hurt. Where is that coffin which

was brought into your house?” “Our time is limited, Watson,” said Holmes. “If

you try to stop us, Peters, you will most certainly get hurt. Where is that coffin which

was brought into your house?”

“What do you want with the coffin? It is in use. There is

a body in it.” “What do you want with the coffin? It is in use. There is

a body in it.”

“I must see that body.” “I must see that body.”

“Never with my consent.” “Never with my consent.”

“Then without it.” With a quick movement Holmes

pushed the fellow to one side and passed into the hall. A door half opened stood

immediately before us. We entered. It was the dining-room. On the table, under a half-lit

chandelier, the coffin was lying. Holmes turned up the gas and raised the lid. Deep down

in the recesses of the coffin lay an emaciated figure. The glare from the lights above

beat down upon an aged and withered face. By no possible process of cruelty, starvation,

or disease could this wornout wreck be the still beautiful Lady Frances. Holmes’s

face showed his amazement, and also his relief. “Then without it.” With a quick movement Holmes

pushed the fellow to one side and passed into the hall. A door half opened stood

immediately before us. We entered. It was the dining-room. On the table, under a half-lit

chandelier, the coffin was lying. Holmes turned up the gas and raised the lid. Deep down

in the recesses of the coffin lay an emaciated figure. The glare from the lights above

beat down upon an aged and withered face. By no possible process of cruelty, starvation,

or disease could this wornout wreck be the still beautiful Lady Frances. Holmes’s

face showed his amazement, and also his relief.

“Thank God!” he muttered. “It’s someone

else.” “Thank God!” he muttered. “It’s someone

else.”

“Ah, you’ve blundered badly for once, Mr. Sherlock

Holmes,” said Peters, who had followed us into the room. “Ah, you’ve blundered badly for once, Mr. Sherlock

Holmes,” said Peters, who had followed us into the room.

“Who is this dead woman?” “Who is this dead woman?”

“Well, if you really must know, she is an old nurse of my

wife’s, Rose Spender [952] by

name, whom we found in the Brixton Workhouse Infirmary. We brought her round here, called

in Dr. Horsom, of 13 Firbank Villas–mind you take the address, Mr. Holmes–and

had her carefully tended, as Christian folk should. On the third day she

died–certificate says senile decay–but that’s only the doctor’s

opinion, and of course you know better. We ordered her funeral to be carried out by

Stimson and Co., of the Kennington Road, who will bury her at eight o’clock to-morrow

morning. Can you pick any hole in that, Mr. Holmes? You’ve made a silly blunder, and

you may as well own up to it. I’d give something for a photograph of your gaping,

staring face when you pulled aside that lid expecting to see the Lady Frances Carfax and

only found a poor old woman of ninety.” “Well, if you really must know, she is an old nurse of my

wife’s, Rose Spender [952] by

name, whom we found in the Brixton Workhouse Infirmary. We brought her round here, called

in Dr. Horsom, of 13 Firbank Villas–mind you take the address, Mr. Holmes–and

had her carefully tended, as Christian folk should. On the third day she

died–certificate says senile decay–but that’s only the doctor’s

opinion, and of course you know better. We ordered her funeral to be carried out by

Stimson and Co., of the Kennington Road, who will bury her at eight o’clock to-morrow

morning. Can you pick any hole in that, Mr. Holmes? You’ve made a silly blunder, and

you may as well own up to it. I’d give something for a photograph of your gaping,

staring face when you pulled aside that lid expecting to see the Lady Frances Carfax and

only found a poor old woman of ninety.”

Holmes’s expression was as impassive as ever under the

jeers of his antagonist, but his clenched hands betrayed his acute annoyance. Holmes’s expression was as impassive as ever under the

jeers of his antagonist, but his clenched hands betrayed his acute annoyance.

“I am going through your house,” said he. “I am going through your house,” said he.

“Are you, though!” cried Peters as a woman’s

voice and heavy steps sounded in the passage. “We’ll soon see about that. This

way, officers, if you please. These men have forced their way into my house, and I cannot

get rid of them. Help me to put them out.” “Are you, though!” cried Peters as a woman’s

voice and heavy steps sounded in the passage. “We’ll soon see about that. This

way, officers, if you please. These men have forced their way into my house, and I cannot

get rid of them. Help me to put them out.”

A sergeant and a constable stood in the doorway. Holmes drew

his card from his case. A sergeant and a constable stood in the doorway. Holmes drew

his card from his case.

“This is my name and address. This is my friend, Dr.

Watson.” “This is my name and address. This is my friend, Dr.

Watson.”

“Bless you, sir, we know you very well,” said the

sergeant, “but you can’t stay here without a warrant.” “Bless you, sir, we know you very well,” said the

sergeant, “but you can’t stay here without a warrant.”

“Of course not. I quite understand that.” “Of course not. I quite understand that.”

“Arrest him!” cried Peters. “Arrest him!” cried Peters.

“We know where to lay our hands on this gentleman if he

is wanted,” said the sergeant majestically, “but you’ll have to go, Mr.

Holmes.” “We know where to lay our hands on this gentleman if he

is wanted,” said the sergeant majestically, “but you’ll have to go, Mr.

Holmes.”

“Yes, Watson, we shall have to go.” “Yes, Watson, we shall have to go.”

A minute later we were in the street once more. Holmes was as

cool as ever, but I was hot with anger and humiliation. The sergeant had followed us. A minute later we were in the street once more. Holmes was as

cool as ever, but I was hot with anger and humiliation. The sergeant had followed us.

“Sorry, Mr. Holmes, but that’s the law.” “Sorry, Mr. Holmes, but that’s the law.”

“Exactly, Sergeant, you could not do otherwise.” “Exactly, Sergeant, you could not do otherwise.”

“I expect there was good reason for your presence there.

If there is anything I can do– –” “I expect there was good reason for your presence there.

If there is anything I can do– –”

“It’s a missing lady, Sergeant, and we think she is

in that house. I expect a warrant presently.” “It’s a missing lady, Sergeant, and we think she is

in that house. I expect a warrant presently.”

“Then I’ll keep my eye on the parties, Mr. Holmes.

If anything comes along, I will surely let you know.” “Then I’ll keep my eye on the parties, Mr. Holmes.

If anything comes along, I will surely let you know.”

It was only nine o’clock, and we were off full cry upon

the trail at once. First we drove to Brixton Workhouse Infirmary, where we found that it

was indeed the truth that a charitable couple had called some days before, that they had

claimed an imbecile old woman as a former servant, and that they had obtained permission

to take her away with them. No surprise was expressed at the news that she had since died. It was only nine o’clock, and we were off full cry upon

the trail at once. First we drove to Brixton Workhouse Infirmary, where we found that it

was indeed the truth that a charitable couple had called some days before, that they had

claimed an imbecile old woman as a former servant, and that they had obtained permission

to take her away with them. No surprise was expressed at the news that she had since died.

The doctor was our next goal. He had been called in, had found

the woman dying of pure senility, had actually seen her pass away, and had signed the

certificate in due form. “I assure you that everything was perfectly normal and there

was no room for foul play in the matter,” said he. Nothing in the house had struck

him as suspicious save that for people of their class it was remarkable that they should

have no servant. So far and no farther went the doctor. The doctor was our next goal. He had been called in, had found

the woman dying of pure senility, had actually seen her pass away, and had signed the

certificate in due form. “I assure you that everything was perfectly normal and there

was no room for foul play in the matter,” said he. Nothing in the house had struck

him as suspicious save that for people of their class it was remarkable that they should

have no servant. So far and no farther went the doctor.

[953] Finally

we found our way to Scotland Yard. There had been difficulties of procedure in regard to

the warrant. Some delay was inevitable. The magistrate’s signature might not be

obtained until next morning. If Holmes would call about nine he could go down with

Lestrade and see it acted upon. So ended the day, save that near midnight our friend, the

sergeant, called to say that he had seen flickering lights here and there in the windows

of the great dark house, but that no one had left it and none had entered. We could but

pray for patience and wait for the morrow. [953] Finally

we found our way to Scotland Yard. There had been difficulties of procedure in regard to

the warrant. Some delay was inevitable. The magistrate’s signature might not be

obtained until next morning. If Holmes would call about nine he could go down with

Lestrade and see it acted upon. So ended the day, save that near midnight our friend, the

sergeant, called to say that he had seen flickering lights here and there in the windows

of the great dark house, but that no one had left it and none had entered. We could but

pray for patience and wait for the morrow.

Sherlock Holmes was too irritable for conversation and too

restless for sleep. I left him smoking hard, with his heavy, dark brows knotted together,

and his long, nervous fingers tapping upon the arms of his chair, as he turned over in his

mind every possible solution of the mystery. Several times in the course of the night I

heard him prowling about the house. Finally, just after I had been called in the morning,

he rushed into my room. He was in his dressing-gown, but his pale, hollow-eyed face told

me that his night had been a sleepless one. Sherlock Holmes was too irritable for conversation and too

restless for sleep. I left him smoking hard, with his heavy, dark brows knotted together,

and his long, nervous fingers tapping upon the arms of his chair, as he turned over in his

mind every possible solution of the mystery. Several times in the course of the night I

heard him prowling about the house. Finally, just after I had been called in the morning,

he rushed into my room. He was in his dressing-gown, but his pale, hollow-eyed face told

me that his night had been a sleepless one.

“What time was the funeral? Eight, was it not?” he

asked eagerly. “Well, it is 7:20 now. Good heavens, Watson, what has become of any

brains that God has given me? Quick, man, quick! It’s life or death–a hundred

chances on death to one on life. I’ll never forgive myself, never, if we are too

late!” “What time was the funeral? Eight, was it not?” he

asked eagerly. “Well, it is 7:20 now. Good heavens, Watson, what has become of any

brains that God has given me? Quick, man, quick! It’s life or death–a hundred

chances on death to one on life. I’ll never forgive myself, never, if we are too

late!”

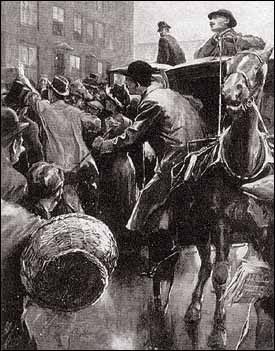

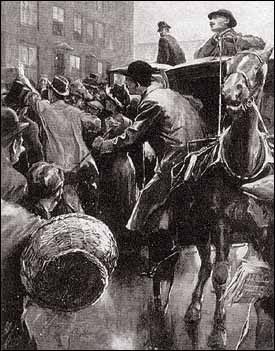

Five minutes had not passed before we were flying in a hansom

down Baker Street. But even so it was twenty-five to eight as we passed Big Ben, and eight

struck as we tore down the Brixton Road. But others were late as well as we. Ten minutes

after the hour the hearse was still standing at the door of the house, and even as our

foaming horse came to a halt the coffin, supported by three men, appeared on the

threshold. Holmes darted forward and barred their way. Five minutes had not passed before we were flying in a hansom

down Baker Street. But even so it was twenty-five to eight as we passed Big Ben, and eight

struck as we tore down the Brixton Road. But others were late as well as we. Ten minutes

after the hour the hearse was still standing at the door of the house, and even as our

foaming horse came to a halt the coffin, supported by three men, appeared on the

threshold. Holmes darted forward and barred their way.

“Take it back!” he cried, laying his hand on the

breast of the foremost. “Take it back this instant!” “Take it back!” he cried, laying his hand on the

breast of the foremost. “Take it back this instant!”

“What the devil do you mean? Once again I ask you, where

is your warrant?” shouted the furious Peters, his big red face glaring over the

farther end of the coffin. “What the devil do you mean? Once again I ask you, where

is your warrant?” shouted the furious Peters, his big red face glaring over the

farther end of the coffin.

“The warrant is on its way. This coffin shall remain in

the house until it comes.” “The warrant is on its way. This coffin shall remain in

the house until it comes.”

The authority in Holmes’s voice had its effect upon the

bearers. Peters had suddenly vanished into the house, and they obeyed these new orders.

“Quick, Watson, quick! Here is a screw-driver!” he shouted as the coffin was

replaced upon the table. “Here’s one for you, my man! A sovereign if the lid

comes off in a minute! Ask no questions–work away! That’s good! Another! And

another! Now pull all together! It’s giving! It’s giving! Ah, that does it at

last.” The authority in Holmes’s voice had its effect upon the

bearers. Peters had suddenly vanished into the house, and they obeyed these new orders.

“Quick, Watson, quick! Here is a screw-driver!” he shouted as the coffin was

replaced upon the table. “Here’s one for you, my man! A sovereign if the lid

comes off in a minute! Ask no questions–work away! That’s good! Another! And

another! Now pull all together! It’s giving! It’s giving! Ah, that does it at

last.”

With a united effort we tore off the coffin-lid. As we did so

there came from the inside a stupefying and overpowering smell of chloroform. A body lay

within, its head all wreathed in cotton-wool, which had been soaked in the narcotic.

Holmes plucked it off and disclosed the statuesque face of a handsome and spiritual woman

of middle age. In an instant he had passed his arm round the figure and raised her to a

sitting position. With a united effort we tore off the coffin-lid. As we did so

there came from the inside a stupefying and overpowering smell of chloroform. A body lay

within, its head all wreathed in cotton-wool, which had been soaked in the narcotic.

Holmes plucked it off and disclosed the statuesque face of a handsome and spiritual woman

of middle age. In an instant he had passed his arm round the figure and raised her to a

sitting position.

“Is she gone, Watson? Is there a spark left? Surely we

are not too late!” “Is she gone, Watson? Is there a spark left? Surely we

are not too late!”

For half an hour it seemed that we were. What with actual

suffocation, and what with the poisonous fumes of the chloroform, the Lady Frances seemed

to have passed the last point of recall. And then, at last, with artificial respiration,

with injected ether, with every device that science could suggest, some flutter of life,

some quiver of the eyelids, some dimming of a mirror, spoke of the slowly [954] returning life. A cab had

driven up, and Holmes, parting the blind, looked out at it. “Here is Lestrade with

his warrant,” said he. “He will find that his birds have flown. And here,”

he added as a heavy step hurried along the passage, “is someone who has a better

right to nurse this lady than we have. Good morning, Mr. Green; I think that the sooner we

can move the Lady Frances the better. Meanwhile, the funeral may proceed, and the poor old

woman who still lies in that coffin may go to her last resting-place alone.” For half an hour it seemed that we were. What with actual

suffocation, and what with the poisonous fumes of the chloroform, the Lady Frances seemed

to have passed the last point of recall. And then, at last, with artificial respiration,

with injected ether, with every device that science could suggest, some flutter of life,

some quiver of the eyelids, some dimming of a mirror, spoke of the slowly [954] returning life. A cab had

driven up, and Holmes, parting the blind, looked out at it. “Here is Lestrade with

his warrant,” said he. “He will find that his birds have flown. And here,”

he added as a heavy step hurried along the passage, “is someone who has a better

right to nurse this lady than we have. Good morning, Mr. Green; I think that the sooner we

can move the Lady Frances the better. Meanwhile, the funeral may proceed, and the poor old

woman who still lies in that coffin may go to her last resting-place alone.”

“Should you care to add the case to your annals, my

dear Watson,” said Holmes that evening, “it can only be as an example of that

temporary eclipse to which even the best-balanced mind may be exposed. Such slips are

common to all mortals, and the greatest is he who can recognize and repair them. To this

modified credit I may, perhaps, make some claim. My night was haunted by the thought that

somewhere a clue, a strange sentence, a curious observation, had come under my notice and

had been too easily dismissed. Then, suddenly, in the gray of the morning, the words came

back to me. It was the remark of the undertaker’s wife, as reported by Philip Green.

She had said, ‘It should be there before now. It took longer, being out of the

ordinary.’ It was the coffin of which she spoke. It had been out of the ordinary.

That could only mean that it had been made to some special measurement. But why? Why? Then

in an instant I remembered the deep sides, and the little wasted figure at the bottom. Why

so large a coffin for so small a body? To leave room for another body. Both would be

buried under the one certificate. It had all been so clear, if only my own sight had not

been dimmed. At eight the Lady Frances would be buried. Our one chance was to stop the

coffin before it left the house. “Should you care to add the case to your annals, my

dear Watson,” said Holmes that evening, “it can only be as an example of that

temporary eclipse to which even the best-balanced mind may be exposed. Such slips are

common to all mortals, and the greatest is he who can recognize and repair them. To this

modified credit I may, perhaps, make some claim. My night was haunted by the thought that

somewhere a clue, a strange sentence, a curious observation, had come under my notice and

had been too easily dismissed. Then, suddenly, in the gray of the morning, the words came

back to me. It was the remark of the undertaker’s wife, as reported by Philip Green.

She had said, ‘It should be there before now. It took longer, being out of the

ordinary.’ It was the coffin of which she spoke. It had been out of the ordinary.

That could only mean that it had been made to some special measurement. But why? Why? Then

in an instant I remembered the deep sides, and the little wasted figure at the bottom. Why

so large a coffin for so small a body? To leave room for another body. Both would be

buried under the one certificate. It had all been so clear, if only my own sight had not

been dimmed. At eight the Lady Frances would be buried. Our one chance was to stop the

coffin before it left the house.

“It was a desperate chance that we might find her alive,

but it was a chance, as the result showed. These people had never, to my knowledge, done a

murder. They might shrink from actual violence at the last. They could bury her with no

sign of how she met her end, and even if she were exhumed there was a chance for them. I

hoped that such considerations might prevail with them. You can reconstruct the scene well

enough. You saw the horrible den upstairs, where the poor lady had been kept so long. They

rushed in and overpowered her with their chloroform, carried her down, poured more into

the coffin to insure against her waking, and then screwed down the lid. A clever device,

Watson. It is new to me in the annals of crime. If our ex-missionary friends escape the

clutches of Lestrade, I shall expect to hear of some brilliant incidents in their future

career.” “It was a desperate chance that we might find her alive,

but it was a chance, as the result showed. These people had never, to my knowledge, done a

murder. They might shrink from actual violence at the last. They could bury her with no

sign of how she met her end, and even if she were exhumed there was a chance for them. I

hoped that such considerations might prevail with them. You can reconstruct the scene well

enough. You saw the horrible den upstairs, where the poor lady had been kept so long. They

rushed in and overpowered her with their chloroform, carried her down, poured more into

the coffin to insure against her waking, and then screwed down the lid. A clever device,

Watson. It is new to me in the annals of crime. If our ex-missionary friends escape the

clutches of Lestrade, I shall expect to hear of some brilliant incidents in their future

career.”

|

![]() “English,” I answered in some surprise. “I got

them at Latimer’s, in Oxford Street.”

“English,” I answered in some surprise. “I got

them at Latimer’s, in Oxford Street.”![]() Holmes smiled with an expression of weary patience.

Holmes smiled with an expression of weary patience.![]() “The bath!” he said; “the bath! Why the

relaxing and expensive Turkish rather than the invigorating home-made article?”

“The bath!” he said; “the bath! Why the

relaxing and expensive Turkish rather than the invigorating home-made article?”![]() “Because for the last few days I have been feeling

rheumatic and old. A Turkish bath is what we call an alterative in medicine–a fresh

starting-point, a cleanser of the system.

“Because for the last few days I have been feeling

rheumatic and old. A Turkish bath is what we call an alterative in medicine–a fresh

starting-point, a cleanser of the system.![]() “By the way, Holmes,” I added, “I have no doubt

the connection between my boots and a Turkish bath is a perfectly self-evident one to a

logical mind, and yet I should be obliged to you if you would indicate it.”

“By the way, Holmes,” I added, “I have no doubt

the connection between my boots and a Turkish bath is a perfectly self-evident one to a

logical mind, and yet I should be obliged to you if you would indicate it.”![]() “The train of reasoning is not very obscure,

Watson,” said Holmes with a mischievous twinkle. “It belongs to the same

elementary class of deduction which I should illustrate if I were to ask you who shared

your cab in your drive this morning.”

“The train of reasoning is not very obscure,

Watson,” said Holmes with a mischievous twinkle. “It belongs to the same

elementary class of deduction which I should illustrate if I were to ask you who shared

your cab in your drive this morning.”![]() “I don’t admit that a fresh illustration is an

explanation,” said I with some asperity.

“I don’t admit that a fresh illustration is an

explanation,” said I with some asperity.![]() “Bravo, Watson! A very dignified and logical

remonstrance. Let me see, what were the points? Take the last one first–the cab. You

observe that you have some splashes on the left sleeve and shoulder of your coat. Had you

sat in the centre of a hansom you would probably have had no splashes, and if you had they

would certainly have been symmetrical. Therefore it is clear that you sat at the side.

Therefore it is equally clear that you had a companion.”

“Bravo, Watson! A very dignified and logical

remonstrance. Let me see, what were the points? Take the last one first–the cab. You

observe that you have some splashes on the left sleeve and shoulder of your coat. Had you

sat in the centre of a hansom you would probably have had no splashes, and if you had they

would certainly have been symmetrical. Therefore it is clear that you sat at the side.

Therefore it is equally clear that you had a companion.”![]() “That is very evident.”

“That is very evident.”![]() “Absurdly commonplace, is it not?”

“Absurdly commonplace, is it not?”![]() “But the boots and the bath?”

“But the boots and the bath?”![]() “Equally childish. You are in the habit of doing up your

boots in a certain way. I see them on this occasion fastened with an elaborate double bow,

which is not your usual method of tying them. You have, therefore, had them off. Who has

tied them? A bootmaker–or the boy at the bath. It is unlikely that it is the

bootmaker, since your boots are nearly new. Well, what remains? The bath. Absurd, is it

not? But, for all that, the Turkish bath has served a purpose.”

“Equally childish. You are in the habit of doing up your

boots in a certain way. I see them on this occasion fastened with an elaborate double bow,

which is not your usual method of tying them. You have, therefore, had them off. Who has

tied them? A bootmaker–or the boy at the bath. It is unlikely that it is the

bootmaker, since your boots are nearly new. Well, what remains? The bath. Absurd, is it

not? But, for all that, the Turkish bath has served a purpose.”![]() “What is that?”

“What is that?”![]() “You say that you have had it because you need a change.

Let me suggest that you take one. How would Lausanne do, my dear Watson–first-class

tickets and all expenses paid on a princely scale?”

“You say that you have had it because you need a change.

Let me suggest that you take one. How would Lausanne do, my dear Watson–first-class

tickets and all expenses paid on a princely scale?”![]() “Splendid! But why?”

“Splendid! But why?”![]() Holmes leaned back in his armchair and took his notebook from

his pocket.

Holmes leaned back in his armchair and took his notebook from

his pocket.![]() “One of the most dangerous classes in the world,”

said he, “is the drifting and friendless woman. She is the most harmless and often

the most useful of mortals, [943] but

she is the inevitable inciter of crime in others. She is helpless. She is migratory. She

has sufficient means to take her from country to country and from hotel to hotel. She is

lost, as often as not, in a maze of obscure pensions and boarding-houses. She is

a stray chicken in a world of foxes. When she is gobbled up she is hardly missed. I much

fear that some evil has come to the Lady Frances Carfax.”

“One of the most dangerous classes in the world,”

said he, “is the drifting and friendless woman. She is the most harmless and often

the most useful of mortals, [943] but

she is the inevitable inciter of crime in others. She is helpless. She is migratory. She

has sufficient means to take her from country to country and from hotel to hotel. She is

lost, as often as not, in a maze of obscure pensions and boarding-houses. She is

a stray chicken in a world of foxes. When she is gobbled up she is hardly missed. I much

fear that some evil has come to the Lady Frances Carfax.”![]() I was relieved at this sudden descent from the general to the

particular. Holmes consulted his notes.

I was relieved at this sudden descent from the general to the

particular. Holmes consulted his notes.![]() “Lady Frances,” he continued, “is the sole

survivor of the direct family of the late Earl of Rufton. The estates went, as you may

remember, in the male line. She was left with limited means, but with some very remarkable

old Spanish jewellery of silver and curiously cut diamonds to which she was fondly

attached–too attached, for she refused to leave them with her banker and always

carried them about with her. A rather pathetic figure, the Lady Frances, a beautiful

woman, still in fresh middle age, and yet, by a strange chance, the last derelict of what

only twenty years ago was a goodly fleet.”

“Lady Frances,” he continued, “is the sole

survivor of the direct family of the late Earl of Rufton. The estates went, as you may

remember, in the male line. She was left with limited means, but with some very remarkable

old Spanish jewellery of silver and curiously cut diamonds to which she was fondly

attached–too attached, for she refused to leave them with her banker and always

carried them about with her. A rather pathetic figure, the Lady Frances, a beautiful

woman, still in fresh middle age, and yet, by a strange chance, the last derelict of what

only twenty years ago was a goodly fleet.”![]() “What has happened to her, then?”

“What has happened to her, then?”![]() “Ah, what has happened to the Lady Frances? Is she alive

or dead? There is our problem. She is a lady of precise habits, and for four years it has

been her invariable custom to write every second week to Miss Dobney, her old governess,

who has long retired and lives in Camberwell. It is this Miss Dobney who has consulted me.

Nearly five weeks have passed without a word. The last letter was from the Hotel National

at Lausanne. Lady Frances seems to have left there and given no address. The family are

anxious, and as they are exceedingly wealthy no sum will be spared if we can clear the

matter up.”

“Ah, what has happened to the Lady Frances? Is she alive

or dead? There is our problem. She is a lady of precise habits, and for four years it has

been her invariable custom to write every second week to Miss Dobney, her old governess,

who has long retired and lives in Camberwell. It is this Miss Dobney who has consulted me.

Nearly five weeks have passed without a word. The last letter was from the Hotel National

at Lausanne. Lady Frances seems to have left there and given no address. The family are

anxious, and as they are exceedingly wealthy no sum will be spared if we can clear the

matter up.”![]() “Is Miss Dobney the only source of information? Surely

she had other correspondents?”

“Is Miss Dobney the only source of information? Surely

she had other correspondents?”![]() “There is one correspondent who is a sure draw, Watson.

That is the bank. Single ladies must live, and their passbooks are compressed diaries. She

banks at Silvester’s. I have glanced over her account. The last check but one paid

her bill at Lausanne, but it was a large one and probably left her with cash in hand. Only

one check has been drawn since.”

“There is one correspondent who is a sure draw, Watson.

That is the bank. Single ladies must live, and their passbooks are compressed diaries. She

banks at Silvester’s. I have glanced over her account. The last check but one paid

her bill at Lausanne, but it was a large one and probably left her with cash in hand. Only

one check has been drawn since.”![]() “To whom, and where?”

“To whom, and where?”![]() “To Miss Marie Devine. There is nothing to show where the

check was drawn. It was cashed at the Cr�dit Lyonnais at Montpellier less than three

weeks ago. The sum was fifty pounds.”

“To Miss Marie Devine. There is nothing to show where the

check was drawn. It was cashed at the Cr�dit Lyonnais at Montpellier less than three

weeks ago. The sum was fifty pounds.”![]() “And who is Miss Marie Devine?”

“And who is Miss Marie Devine?”![]() “That also I have been able to discover. Miss Marie