|

|

I was weary of our little sitting-room and gladly acquiesced.

For three hours we strolled about together, watching the ever-changing kaleidoscope of

life as it ebbs and flows through Fleet Street and the Strand. His characteristic talk,

with its keen observance of detail and subtle power of inference, held me amused and

enthralled. It was ten o’clock before we reached Baker Street again. A brougham was

waiting at our door. I was weary of our little sitting-room and gladly acquiesced.

For three hours we strolled about together, watching the ever-changing kaleidoscope of

life as it ebbs and flows through Fleet Street and the Strand. His characteristic talk,

with its keen observance of detail and subtle power of inference, held me amused and

enthralled. It was ten o’clock before we reached Baker Street again. A brougham was

waiting at our door.

“Hum! A doctor’s–general practitioner, I

perceive,” said Holmes. “Not been long in practice, but has a good deal to do.

Come to consult us, I fancy! Lucky we came back!” “Hum! A doctor’s–general practitioner, I

perceive,” said Holmes. “Not been long in practice, but has a good deal to do.

Come to consult us, I fancy! Lucky we came back!”

I was sufficiently conversant with Holmes’s methods to be

able to follow his reasoning, and to see that the nature and state of the various medical

instruments in the wicker basket which hung in the lamp-light inside the brougham had

given him the data for his swift deduction. The light in our window above showed that this

late visit was indeed intended for us. With some curiosity as to what could have sent a

brother medico to us at such an hour, I followed Holmes into our sanctum. I was sufficiently conversant with Holmes’s methods to be

able to follow his reasoning, and to see that the nature and state of the various medical

instruments in the wicker basket which hung in the lamp-light inside the brougham had

given him the data for his swift deduction. The light in our window above showed that this

late visit was indeed intended for us. With some curiosity as to what could have sent a

brother medico to us at such an hour, I followed Holmes into our sanctum.

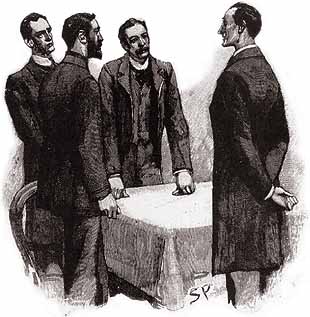

A pale, taper-faced man with sandy whiskers rose up from a

chair by the fire as we entered. His age may not have been more than three or four and

thirty, but his haggard expression and unhealthy hue told of a life which had sapped his

strength and robbed him of his youth. His manner was nervous and shy, like that of a [425] sensitive gentleman, and the

thin white hand which he laid on the mantelpiece as he rose was that of an artist rather

than of a surgeon. His dress was quiet and sombre–a black frock-coat, dark trousers,

and a touch of colour about his necktie. A pale, taper-faced man with sandy whiskers rose up from a

chair by the fire as we entered. His age may not have been more than three or four and

thirty, but his haggard expression and unhealthy hue told of a life which had sapped his

strength and robbed him of his youth. His manner was nervous and shy, like that of a [425] sensitive gentleman, and the

thin white hand which he laid on the mantelpiece as he rose was that of an artist rather

than of a surgeon. His dress was quiet and sombre–a black frock-coat, dark trousers,

and a touch of colour about his necktie.

“Good-evening, Doctor,” said Holmes cheerily.

“I am glad to see that you have only been waiting a very few minutes.” “Good-evening, Doctor,” said Holmes cheerily.

“I am glad to see that you have only been waiting a very few minutes.”

“You spoke to my coachman, then?” “You spoke to my coachman, then?”

“No, it was the candle on the side-table that told me.

Pray resume your seat and let me know how I can serve you.” “No, it was the candle on the side-table that told me.

Pray resume your seat and let me know how I can serve you.”

“My name is Dr. Percy Trevelyan,” said our visitor,

“and I live at 403 Brook Street.” “My name is Dr. Percy Trevelyan,” said our visitor,

“and I live at 403 Brook Street.”

“Are you not the author of a monograph upon obscure

nervous lesions?” I asked. “Are you not the author of a monograph upon obscure

nervous lesions?” I asked.

His pale cheeks flushed with pleasure at hearing that his work

was known to me. His pale cheeks flushed with pleasure at hearing that his work

was known to me.

“I so seldom hear of the work that I thought it was quite

dead,” said he. “My publishers gave me a most discouraging account of its sale.

You are yourself, I presume, a medical man?” “I so seldom hear of the work that I thought it was quite

dead,” said he. “My publishers gave me a most discouraging account of its sale.

You are yourself, I presume, a medical man?”

“A retired army surgeon.” “A retired army surgeon.”

“My own hobby has always been nervous disease. I should

wish to make it an absolute specialty, but of course a man must take what he can get at

first. This, however, is beside the question, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and I quite appreciate

how valuable your time is. The fact is that a very singular train of events has occurred

recently at my house in Brook Street, and to-night they came to such a head that I felt it

was quite impossible for me to wait another hour before asking for your advice and

assistance.” “My own hobby has always been nervous disease. I should

wish to make it an absolute specialty, but of course a man must take what he can get at

first. This, however, is beside the question, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and I quite appreciate

how valuable your time is. The fact is that a very singular train of events has occurred

recently at my house in Brook Street, and to-night they came to such a head that I felt it

was quite impossible for me to wait another hour before asking for your advice and

assistance.”

Sherlock Holmes sat down and lit his pipe. “You are very

welcome to both,” said he. “Pray let me have a detailed account of what the

circumstances are which have disturbed you.” Sherlock Holmes sat down and lit his pipe. “You are very

welcome to both,” said he. “Pray let me have a detailed account of what the

circumstances are which have disturbed you.”

“One or two of them are so trivial,” said Dr.

Trevelyan, “that really I am almost ashamed to mention them. But the matter is so

inexplicable, and the recent turn which it has taken is so elaborate, that I shall lay it

all before you, and you shall judge what is essential and what is not. “One or two of them are so trivial,” said Dr.

Trevelyan, “that really I am almost ashamed to mention them. But the matter is so

inexplicable, and the recent turn which it has taken is so elaborate, that I shall lay it

all before you, and you shall judge what is essential and what is not.

“I am compelled, to begin with, to say something of my

own college career. I am a London University man, you know, and I am sure that you will

not think that I am unduly singing my own praises if I say that my student career was

considered by my professors to be a very promising one. After I had graduated I continued

to devote myself to research, occupying a minor position in King’s College Hospital,

and I was fortunate enough to excite considerable interest by my research into the

pathology of catalepsy, and finally to win the Bruce Pinkerton prize and medal by the

monograph on nervous lesions to which your friend has just alluded. I should not go too

far if I were to say that there was a general impression at that time that a distinguished

career lay before me. “I am compelled, to begin with, to say something of my

own college career. I am a London University man, you know, and I am sure that you will

not think that I am unduly singing my own praises if I say that my student career was

considered by my professors to be a very promising one. After I had graduated I continued

to devote myself to research, occupying a minor position in King’s College Hospital,

and I was fortunate enough to excite considerable interest by my research into the

pathology of catalepsy, and finally to win the Bruce Pinkerton prize and medal by the

monograph on nervous lesions to which your friend has just alluded. I should not go too

far if I were to say that there was a general impression at that time that a distinguished

career lay before me.

“But the one great stumbling-block lay in my want of

capital. As you will readily understand, a specialist who aims high is compelled to start

in one of a dozen streets in the Cavendish Square quarter, all of which entail enormous

rents and furnishing expenses. Besides this preliminary outlay, he must be prepared to

keep himself for some years, and to hire a presentable carriage and horse. To do this was

quite beyond my power, and I could only hope that by economy I might in ten years’

time save enough to enable me to put up my plate. Suddenly, however, an unexpected

incident opened up quite a new prospect to me. “But the one great stumbling-block lay in my want of

capital. As you will readily understand, a specialist who aims high is compelled to start

in one of a dozen streets in the Cavendish Square quarter, all of which entail enormous

rents and furnishing expenses. Besides this preliminary outlay, he must be prepared to

keep himself for some years, and to hire a presentable carriage and horse. To do this was

quite beyond my power, and I could only hope that by economy I might in ten years’

time save enough to enable me to put up my plate. Suddenly, however, an unexpected

incident opened up quite a new prospect to me.

“This was a visit from a gentleman of the name of

Blessington, who was a [426] complete

stranger to me. He came up into my room one morning, and plunged into business in an

instant. “This was a visit from a gentleman of the name of

Blessington, who was a [426] complete

stranger to me. He came up into my room one morning, and plunged into business in an

instant.

“ ‘You are the same Percy Trevelyan who has had so

distinguished a career and won a great prize lately?’ said he. “ ‘You are the same Percy Trevelyan who has had so

distinguished a career and won a great prize lately?’ said he.

“I bowed. “I bowed.

“ ‘Answer me frankly,’ he continued, ‘for

you will find it to your interest to do so. You have all the cleverness which makes a

successful man. Have you the tact?’ “ ‘Answer me frankly,’ he continued, ‘for

you will find it to your interest to do so. You have all the cleverness which makes a

successful man. Have you the tact?’

“I could not help smiling at the abruptness of the

question. “I could not help smiling at the abruptness of the

question.

“ ‘I trust that I have my share,’ I said. “ ‘I trust that I have my share,’ I said.

“ ‘Any bad habits? Not drawn towards drink,

eh?’ “ ‘Any bad habits? Not drawn towards drink,

eh?’

“ ‘Really, sir!’ I cried. “ ‘Really, sir!’ I cried.

“ ‘Quite right! That’s all right! But I was

bound to ask. With all these qualities, why are you not in practice?’ “ ‘Quite right! That’s all right! But I was

bound to ask. With all these qualities, why are you not in practice?’

“I shrugged my shoulders. “I shrugged my shoulders.

“ ‘Come, come!’ said he in his bustling way.

‘It’s the old story. More in your brains than in your pocket, eh? What would you

say if I were to start you in Brook Street?’ “ ‘Come, come!’ said he in his bustling way.

‘It’s the old story. More in your brains than in your pocket, eh? What would you

say if I were to start you in Brook Street?’

“I stared at him in astonishment. “I stared at him in astonishment.

“ ‘Oh, it’s for my sake, not for yours,’

he cried. ‘I’ll be perfectly frank with you, and if it suits you it will suit me

very well. I have a few thousands to invest, d’ye see, and I think I’ll sink

them in you.’ “ ‘Oh, it’s for my sake, not for yours,’

he cried. ‘I’ll be perfectly frank with you, and if it suits you it will suit me

very well. I have a few thousands to invest, d’ye see, and I think I’ll sink

them in you.’

“ ‘But why?’ I gasped. “ ‘But why?’ I gasped.

“ ‘Well, it’s just like any other speculation,

and safer than most.’ “ ‘Well, it’s just like any other speculation,

and safer than most.’

“ ‘What am I to do, then?’ “ ‘What am I to do, then?’

“ ‘I’ll tell you. I’ll take the house,

furnish it, pay the maids, and run the whole place. All you have to do is just to wear out

your chair in the consulting-room. I’ll let you have pocket-money and everything.

Then you hand over to me three quarters of what you earn, and you keep the other quarter

for yourself.’ “ ‘I’ll tell you. I’ll take the house,

furnish it, pay the maids, and run the whole place. All you have to do is just to wear out

your chair in the consulting-room. I’ll let you have pocket-money and everything.

Then you hand over to me three quarters of what you earn, and you keep the other quarter

for yourself.’

“This was the strange proposal, Mr. Holmes, with which

the man Blessington approached me. I won’t weary you with the account of how we

bargained and negotiated. It ended in my moving into the house next Lady Day, and starting

in practice on very much the same conditions as he had suggested. He came himself to live

with me in the character of a resident patient. His heart was weak, it appears, and he

needed constant medical supervision. He turned the two best rooms of the first floor into

a sitting-room and bedroom for himself. He was a man of singular habits, shunning company

and very seldom going out. His life was irregular, but in one respect he was regularity

itself. Every evening, at the same hour, he walked into the consulting-room, examined the

books, put down five and three-pence for every guinea that I had earned, and carried the

rest off to the strong-box in his own room. “This was the strange proposal, Mr. Holmes, with which

the man Blessington approached me. I won’t weary you with the account of how we

bargained and negotiated. It ended in my moving into the house next Lady Day, and starting

in practice on very much the same conditions as he had suggested. He came himself to live

with me in the character of a resident patient. His heart was weak, it appears, and he

needed constant medical supervision. He turned the two best rooms of the first floor into

a sitting-room and bedroom for himself. He was a man of singular habits, shunning company

and very seldom going out. His life was irregular, but in one respect he was regularity

itself. Every evening, at the same hour, he walked into the consulting-room, examined the

books, put down five and three-pence for every guinea that I had earned, and carried the

rest off to the strong-box in his own room.

“I may say with confidence that he never had occasion to

regret his speculation. From the first it was a success. A few good cases and the

reputation which I had won in the hospital brought me rapidly to the front, and during the

last few years I have made him a rich man. “I may say with confidence that he never had occasion to

regret his speculation. From the first it was a success. A few good cases and the

reputation which I had won in the hospital brought me rapidly to the front, and during the

last few years I have made him a rich man.

“So much, Mr. Holmes, for my past history and my

relations with Mr. Blessington. It only remains for me now to tell you what has occurred

to bring me here to-night. “So much, Mr. Holmes, for my past history and my

relations with Mr. Blessington. It only remains for me now to tell you what has occurred

to bring me here to-night.

“Some weeks ago Mr. Blessington came down to me in, as it

seemed to me, a state of considerable agitation. He spoke of some burglary which, he said,

had been [427] committed in

the West End, and he appeared, I remember, to be quite unnecessarily excited about it,

declaring that a day should not pass before we should add stronger bolts to our windows

and doors. For a week he continued to be in a peculiar state of restlessness, peering

continually out of the windows, and ceasing to take the short walk which had usually been

the prelude to his dinner. From his manner it struck me that he was in mortal dread of

something or somebody, but when I questioned him upon the point he became so offensive

that I was compelled to drop the subject. Gradually, as time passed, his fears appeared to

die away, and he renewed his former habits, when a fresh event reduced him to the pitiable

state of prostration in which he now lies. “Some weeks ago Mr. Blessington came down to me in, as it

seemed to me, a state of considerable agitation. He spoke of some burglary which, he said,

had been [427] committed in

the West End, and he appeared, I remember, to be quite unnecessarily excited about it,

declaring that a day should not pass before we should add stronger bolts to our windows

and doors. For a week he continued to be in a peculiar state of restlessness, peering

continually out of the windows, and ceasing to take the short walk which had usually been

the prelude to his dinner. From his manner it struck me that he was in mortal dread of

something or somebody, but when I questioned him upon the point he became so offensive

that I was compelled to drop the subject. Gradually, as time passed, his fears appeared to

die away, and he renewed his former habits, when a fresh event reduced him to the pitiable

state of prostration in which he now lies.

“What happened was this. Two days ago I received the

letter which I now read to you. Neither address nor date is attached to it. “What happened was this. Two days ago I received the

letter which I now read to you. Neither address nor date is attached to it.

“A Russian nobleman who is now resident in England [it

runs], would be glad to avail himself of the professional assistance of Dr. Percy

Trevelyan. He has been for some years a victim to cataleptic attacks, on which, as is well

known, Dr. Trevelyan is an authority. He proposes to call at about a quarter-past six

to-morrow evening, if Dr. Trevelyan will make it convenient to be at home. “A Russian nobleman who is now resident in England [it

runs], would be glad to avail himself of the professional assistance of Dr. Percy

Trevelyan. He has been for some years a victim to cataleptic attacks, on which, as is well

known, Dr. Trevelyan is an authority. He proposes to call at about a quarter-past six

to-morrow evening, if Dr. Trevelyan will make it convenient to be at home.

“This letter interested me deeply, because the chief

difficulty in the study of catalepsy is the rareness of the disease. You may believe,

then, that I was in my consulting-room when, at the appointed hour, the page showed in the

patient. “This letter interested me deeply, because the chief

difficulty in the study of catalepsy is the rareness of the disease. You may believe,

then, that I was in my consulting-room when, at the appointed hour, the page showed in the

patient.

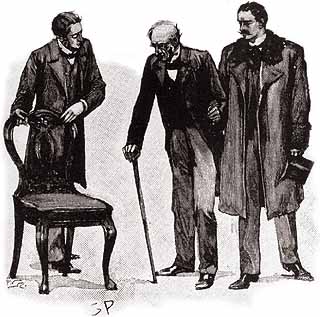

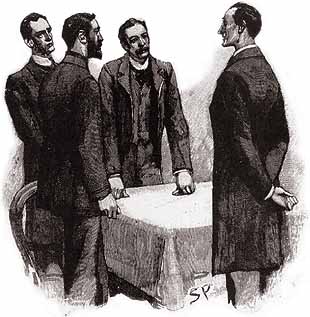

“He was an elderly man, thin, demure, and

commonplace–by no means the conception one forms of a Russian nobleman. I was much

more struck by the appearance of his companion. This was a tall young man, surprisingly

handsome, with a dark, fierce face, and the limbs and chest of a Hercules. He had his hand

under the other’s arm as they entered, and helped him to a chair with a tenderness

which one would hardly have expected from his appearance. “He was an elderly man, thin, demure, and

commonplace–by no means the conception one forms of a Russian nobleman. I was much

more struck by the appearance of his companion. This was a tall young man, surprisingly

handsome, with a dark, fierce face, and the limbs and chest of a Hercules. He had his hand

under the other’s arm as they entered, and helped him to a chair with a tenderness

which one would hardly have expected from his appearance.

“ ‘You will excuse my coming in, Doctor,’

said he to me, speaking English with a slight lisp. ‘This is my father, and his

health is a matter of the most overwhelming importance to me.’ “ ‘You will excuse my coming in, Doctor,’

said he to me, speaking English with a slight lisp. ‘This is my father, and his

health is a matter of the most overwhelming importance to me.’

“I was touched by this filial anxiety. ‘You would,

perhaps, care to remain during the consultation?’ said I. “I was touched by this filial anxiety. ‘You would,

perhaps, care to remain during the consultation?’ said I.

“ ‘Not for the world,’ he cried with a gesture

of horror. ‘It is more painful to me than I can express. If I were to see my father

in one of these dreadful seizures I am convinced that I should never survive it. My own

nervous system is an exceptionally sensitive one. With your permission, I will remain in

the waiting-room while you go into my father’s case.’ “ ‘Not for the world,’ he cried with a gesture

of horror. ‘It is more painful to me than I can express. If I were to see my father

in one of these dreadful seizures I am convinced that I should never survive it. My own

nervous system is an exceptionally sensitive one. With your permission, I will remain in

the waiting-room while you go into my father’s case.’

“To this, of course, I assented, and the young man

withdrew. The patient and I then plunged into a discussion of his case, of which I took

exhaustive notes. He was not remarkable for intelligence, and his answers were frequently

obscure, which I attributed to his limited acquaintance with our language. Suddenly,

however, as I sat writing, he ceased to give any answer at all to my inquiries, and on my

turning towards him I was shocked to see that he was sitting bolt upright in his chair,

staring at me with a perfectly blank and rigid face. He was again in the grip of his

mysterious malady. “To this, of course, I assented, and the young man

withdrew. The patient and I then plunged into a discussion of his case, of which I took

exhaustive notes. He was not remarkable for intelligence, and his answers were frequently

obscure, which I attributed to his limited acquaintance with our language. Suddenly,

however, as I sat writing, he ceased to give any answer at all to my inquiries, and on my

turning towards him I was shocked to see that he was sitting bolt upright in his chair,

staring at me with a perfectly blank and rigid face. He was again in the grip of his

mysterious malady.

“My first feeling, as I have just said, was one of

pity and horror. My second, I fear, was rather one of professional satisfaction. I made

notes of my patient’s pulse and temperature, tested the rigidity of his muscles, and

examined his [428] reflexes.

There was nothing markedly abnormal in any of these conditions, which harmonized with my

former experiences. I had obtained good results in such cases by the inhalation of nitrite

of amyl, and the present seemed an admirable opportunity of testing its virtues. The

bottle was downstairs in my laboratory, so, leaving my patient seated in his chair, I ran

down to get it. There was some little delay in finding it–five minutes, let us

say–and then I returned. Imagine my amazement to find the room empty and the patient

gone. “My first feeling, as I have just said, was one of

pity and horror. My second, I fear, was rather one of professional satisfaction. I made

notes of my patient’s pulse and temperature, tested the rigidity of his muscles, and

examined his [428] reflexes.

There was nothing markedly abnormal in any of these conditions, which harmonized with my

former experiences. I had obtained good results in such cases by the inhalation of nitrite

of amyl, and the present seemed an admirable opportunity of testing its virtues. The

bottle was downstairs in my laboratory, so, leaving my patient seated in his chair, I ran

down to get it. There was some little delay in finding it–five minutes, let us

say–and then I returned. Imagine my amazement to find the room empty and the patient

gone.

“Of course, my first act was to run into the

waiting-room. The son had gone also. The hall door had been closed, but not shut. My page

who admits patients is a new boy and by no means quick. He waits downstairs and runs up to

show patients out when I ring the consulting-room bell. He had heard nothing, and the

affair remained a complete mystery. Mr. Blessington came in from his walk shortly

afterwards, but I did not say anything to him upon the subject, for, to tell the truth, I

have got in the way of late of holding as little communication with him as possible. “Of course, my first act was to run into the

waiting-room. The son had gone also. The hall door had been closed, but not shut. My page

who admits patients is a new boy and by no means quick. He waits downstairs and runs up to

show patients out when I ring the consulting-room bell. He had heard nothing, and the

affair remained a complete mystery. Mr. Blessington came in from his walk shortly

afterwards, but I did not say anything to him upon the subject, for, to tell the truth, I

have got in the way of late of holding as little communication with him as possible.

“Well, I never thought that I should see anything more of

the Russian and his son, so you can imagine my amazement when, at the very same hour this

evening, they both came marching into my consulting-room, just as they had done before. “Well, I never thought that I should see anything more of

the Russian and his son, so you can imagine my amazement when, at the very same hour this

evening, they both came marching into my consulting-room, just as they had done before.

“ ‘I feel that I owe you a great many apologies for

my abrupt departure yesterday, Doctor,’ said my patient. “ ‘I feel that I owe you a great many apologies for

my abrupt departure yesterday, Doctor,’ said my patient.

“ ‘I confess that I was very much surprised at

it,’ said I. “ ‘I confess that I was very much surprised at

it,’ said I.

“ ‘Well, the fact is,’ he remarked, ‘that

when I recover from these attacks my mind is always very clouded as to all that has gone

before. I woke up in a strange room, as it seemed to me, and made my way out into the

street in a sort of dazed way when you were absent.’ “ ‘Well, the fact is,’ he remarked, ‘that

when I recover from these attacks my mind is always very clouded as to all that has gone

before. I woke up in a strange room, as it seemed to me, and made my way out into the

street in a sort of dazed way when you were absent.’

“ ‘And I,’ said the son, ‘seeing my father

pass the door of the waiting-room, naturally thought that the consultation had come to an

end. It was not until we had reached home that I began to realize the true state of

affairs.’ “ ‘And I,’ said the son, ‘seeing my father

pass the door of the waiting-room, naturally thought that the consultation had come to an

end. It was not until we had reached home that I began to realize the true state of

affairs.’

“ ‘Well,’ said I, laughing, ‘there is no

harm done except that you puzzled me terribly; so if you, sir, would kindly step into the

waiting-room I shall be happy to continue our consultation which was brought to so abrupt

an ending.’ “ ‘Well,’ said I, laughing, ‘there is no

harm done except that you puzzled me terribly; so if you, sir, would kindly step into the

waiting-room I shall be happy to continue our consultation which was brought to so abrupt

an ending.’

“For half an hour or so I discussed the old

gentleman’s symptoms with him, and then, having prescribed for him, I saw him go off

upon the arm of his son. “For half an hour or so I discussed the old

gentleman’s symptoms with him, and then, having prescribed for him, I saw him go off

upon the arm of his son.

“I have told you that Mr. Blessington generally chose

this hour of the day for his exercise. He came in shortly afterwards and passed upstairs.

An instant later I heard him running down, and he burst into my consulting-room like a man

who is mad with panic. “I have told you that Mr. Blessington generally chose

this hour of the day for his exercise. He came in shortly afterwards and passed upstairs.

An instant later I heard him running down, and he burst into my consulting-room like a man

who is mad with panic.

“ ‘Who has been in my room?’ he cried. “ ‘Who has been in my room?’ he cried.

“ ‘No one,’ said I. “ ‘No one,’ said I.

“ ‘It’s a lie!’ he yelled. ‘Come up

and look!’ “ ‘It’s a lie!’ he yelled. ‘Come up

and look!’

“I passed over the grossness of his language, as he

seemed half out of his mind with fear. When I went upstairs with him he pointed to several

footprints upon the light carpet. “I passed over the grossness of his language, as he

seemed half out of his mind with fear. When I went upstairs with him he pointed to several

footprints upon the light carpet.

“ ‘Do you mean to say those are mine?’ he

cried. “ ‘Do you mean to say those are mine?’ he

cried.

“They were certainly very much larger than any which he

could have made, and were evidently quite fresh. It rained hard this afternoon, as you

know, and my patients were the only people who called. It must have been the case, then,

that the man in the waiting-room had, for some unknown reason, while I was busy with the

other, ascended to the room of my resident patient. Nothing had been touched [429] or taken, but there were the

footprints to prove that the intrusion was an undoubted fact. “They were certainly very much larger than any which he

could have made, and were evidently quite fresh. It rained hard this afternoon, as you

know, and my patients were the only people who called. It must have been the case, then,

that the man in the waiting-room had, for some unknown reason, while I was busy with the

other, ascended to the room of my resident patient. Nothing had been touched [429] or taken, but there were the

footprints to prove that the intrusion was an undoubted fact.

“Mr. Blessington seemed more excited over the matter than

I should have thought possible, though of course it was enough to disturb anybody’s

peace of mind. He actually sat crying in an armchair, and I could hardly get him to speak

coherently. It was his suggestion that I should come round to you, and of course I at once

saw the propriety of it, for certainly the incident is a very singular one, though he

appears to completely overrate its importance. If you would only come back with me in my

brougham, you would at least be able to soothe him, though I can hardly hope that you will

be able to explain this remarkable occurrence.” “Mr. Blessington seemed more excited over the matter than

I should have thought possible, though of course it was enough to disturb anybody’s

peace of mind. He actually sat crying in an armchair, and I could hardly get him to speak

coherently. It was his suggestion that I should come round to you, and of course I at once

saw the propriety of it, for certainly the incident is a very singular one, though he

appears to completely overrate its importance. If you would only come back with me in my

brougham, you would at least be able to soothe him, though I can hardly hope that you will

be able to explain this remarkable occurrence.”

Sherlock Holmes had listened to this long narrative with an

intentness which showed me that his interest was keenly aroused. His face was as impassive

as ever, but his lids had drooped more heavily over his eyes, and his smoke had curled up

more thickly from his pipe to emphasize each curious episode in the doctor’s tale. As

our visitor concluded, Holmes sprang up without a word, handed me my hat, picked his own

from the table, and followed Dr. Trevelyan to the door. Within a quarter of an hour we had

been dropped at the door of the physician’s residence in Brook Street, one of those

sombre, flat-faced houses which one associates with a West End practice. A small page

admitted us, and we began at once to ascend the broad, well-carpeted stair. Sherlock Holmes had listened to this long narrative with an

intentness which showed me that his interest was keenly aroused. His face was as impassive

as ever, but his lids had drooped more heavily over his eyes, and his smoke had curled up

more thickly from his pipe to emphasize each curious episode in the doctor’s tale. As

our visitor concluded, Holmes sprang up without a word, handed me my hat, picked his own

from the table, and followed Dr. Trevelyan to the door. Within a quarter of an hour we had

been dropped at the door of the physician’s residence in Brook Street, one of those

sombre, flat-faced houses which one associates with a West End practice. A small page

admitted us, and we began at once to ascend the broad, well-carpeted stair.

But a singular interruption brought us to a standstill. The

light at the top was suddenly whisked out, and from the darkness came a reedy, quavering

voice. But a singular interruption brought us to a standstill. The

light at the top was suddenly whisked out, and from the darkness came a reedy, quavering

voice.

“I have a pistol,” it cried. “I give you my

word that I’ll fire if you come any nearer.” “I have a pistol,” it cried. “I give you my

word that I’ll fire if you come any nearer.”

“This really grows outrageous, Mr. Blessington,”

cried Dr. Trevelyan. “This really grows outrageous, Mr. Blessington,”

cried Dr. Trevelyan.

“Oh, then it is you, Doctor,” said the voice with a

great heave of relief. “But those other gentlemen, are they what they pretend to

be?” “Oh, then it is you, Doctor,” said the voice with a

great heave of relief. “But those other gentlemen, are they what they pretend to

be?”

We were conscious of a long scrutiny out of the darkness. We were conscious of a long scrutiny out of the darkness.

“Yes, yes, it’s all right,” said the voice at

last. “You can come up, and I am sorry if my precautions have annoyed you.” “Yes, yes, it’s all right,” said the voice at

last. “You can come up, and I am sorry if my precautions have annoyed you.”

He relit the stair gas as he spoke, and we saw before us a

singular-looking man, whose appearance, as well as his voice, testified to his jangled

nerves. He was very fat, but had apparently at some time been much fatter, so that the

skin hung about his face in loose pouches, like the cheeks of a bloodhound. He was of a

sickly colour, and his thin, sandy hair seemed to bristle up with the intensity of his

emotion. In his hand he held a pistol, but he thrust it into his pocket as we advanced. He relit the stair gas as he spoke, and we saw before us a

singular-looking man, whose appearance, as well as his voice, testified to his jangled

nerves. He was very fat, but had apparently at some time been much fatter, so that the

skin hung about his face in loose pouches, like the cheeks of a bloodhound. He was of a

sickly colour, and his thin, sandy hair seemed to bristle up with the intensity of his

emotion. In his hand he held a pistol, but he thrust it into his pocket as we advanced.

“Good-evening, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “I am

sure I am very much obliged to you for coming round. No one ever needed your advice more

than I do. I suppose that Dr. Trevelyan has told you of this most unwarrantable intrusion

into my rooms.” “Good-evening, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “I am

sure I am very much obliged to you for coming round. No one ever needed your advice more

than I do. I suppose that Dr. Trevelyan has told you of this most unwarrantable intrusion

into my rooms.”

“Quite so,” said Holmes. “Who are these two

men, Mr. Blessington, and why do they wish to molest you?” “Quite so,” said Holmes. “Who are these two

men, Mr. Blessington, and why do they wish to molest you?”

“Well, well,” said the resident patient in a nervous

fashion, “of course it is hard to say that. You can hardly expect me to answer that,

Mr. Holmes.” “Well, well,” said the resident patient in a nervous

fashion, “of course it is hard to say that. You can hardly expect me to answer that,

Mr. Holmes.”

“Do you mean that you don’t know?” “Do you mean that you don’t know?”

“Come in here, if you please. Just have the kindness to

step in here.” “Come in here, if you please. Just have the kindness to

step in here.”

He led the way into his bedroom, which was large and

comfortably furnished. He led the way into his bedroom, which was large and

comfortably furnished.

“You see that,” said he, pointing to a big black box

at the end of his bed. “I have never been a very rich man, Mr. Holmes–never made

but one investment in [430] my

life, as Dr. Trevelyan would tell you. But I don’t believe in bankers. I would never

trust a banker, Mr. Holmes. Between ourselves, what little I have is in that box, so you

can understand what it means to me when unknown people force themselves into my

rooms.” “You see that,” said he, pointing to a big black box

at the end of his bed. “I have never been a very rich man, Mr. Holmes–never made

but one investment in [430] my

life, as Dr. Trevelyan would tell you. But I don’t believe in bankers. I would never

trust a banker, Mr. Holmes. Between ourselves, what little I have is in that box, so you

can understand what it means to me when unknown people force themselves into my

rooms.”

Holmes looked at Blessington in his questioning way and shook

his head. Holmes looked at Blessington in his questioning way and shook

his head.

“I cannot possibly advise you if you try to deceive

me,” said he. “I cannot possibly advise you if you try to deceive

me,” said he.

“But I have told you everything.” “But I have told you everything.”

Holmes turned on his heel with a gesture of disgust.

“Good-night, Dr. Trevelyan,” said he. Holmes turned on his heel with a gesture of disgust.

“Good-night, Dr. Trevelyan,” said he.

“And no advice for me?” cried Blessington in a

breaking voice. “And no advice for me?” cried Blessington in a

breaking voice.

“My advice to you, sir, is to speak the truth.” “My advice to you, sir, is to speak the truth.”

A minute later we were in the street and walking for home. We

had crossed Oxford Street and were halfway down Harley Street before I could get a word

from my companion. A minute later we were in the street and walking for home. We

had crossed Oxford Street and were halfway down Harley Street before I could get a word

from my companion.

“Sorry to bring you out on such a fool’s errand,

Watson,” he said at last. “It is an interesting case, too, at the bottom of

it.” “Sorry to bring you out on such a fool’s errand,

Watson,” he said at last. “It is an interesting case, too, at the bottom of

it.”

“I can make little of it,” I confessed. “I can make little of it,” I confessed.

“Well, it is quite evident that there are two

men–more, perhaps, but at least two–who are determined for some reason to get at

this fellow Blessington. I have no doubt in my mind that both on the first and on the

second occasion that young man penetrated to Blessington’s room, while his

confederate, by an ingenious device, kept the doctor from interfering.” “Well, it is quite evident that there are two

men–more, perhaps, but at least two–who are determined for some reason to get at

this fellow Blessington. I have no doubt in my mind that both on the first and on the

second occasion that young man penetrated to Blessington’s room, while his

confederate, by an ingenious device, kept the doctor from interfering.”

“And the catalepsy?” “And the catalepsy?”

“A fraudulent imitation, Watson, though I should hardly

dare to hint as much to our specialist. It is a very easy complaint to imitate. I have

done it myself.” “A fraudulent imitation, Watson, though I should hardly

dare to hint as much to our specialist. It is a very easy complaint to imitate. I have

done it myself.”

“And then?” “And then?”

“By the purest chance Blessington was out on each

occasion. Their reason for choosing so unusual an hour for a consultation was obviously to

insure that there should be no other patient in the waiting-room. It just happened,

however, that this hour coincided with Blessington’s constitutional, which seems to

show that they were not very well acquainted with his daily routine. Of course, if they

had been merely after plunder they would at least have made some attempt to search for it.

Besides, I can read in a man’s eye when it is his own skin that he is frightened for.

It is inconceivable that this fellow could have made two such vindictive enemies as these

appear to be without knowing of it. I hold it, therefore, to be certain that he does know

who these men are, and that for reasons of his own he suppresses it. It is just possible

that to-morrow may find him in a more communicative mood.” “By the purest chance Blessington was out on each

occasion. Their reason for choosing so unusual an hour for a consultation was obviously to

insure that there should be no other patient in the waiting-room. It just happened,

however, that this hour coincided with Blessington’s constitutional, which seems to

show that they were not very well acquainted with his daily routine. Of course, if they

had been merely after plunder they would at least have made some attempt to search for it.

Besides, I can read in a man’s eye when it is his own skin that he is frightened for.

It is inconceivable that this fellow could have made two such vindictive enemies as these

appear to be without knowing of it. I hold it, therefore, to be certain that he does know

who these men are, and that for reasons of his own he suppresses it. It is just possible

that to-morrow may find him in a more communicative mood.”

“Is there not one alternative,” I suggested,

“grotesquely improbable, no doubt, but still just conceivable? Might the whole story

of the cataleptic Russian and his son be a concoction of Dr. Trevelyan’s, who has,

for his own purposes, been in Blessington’s rooms?” “Is there not one alternative,” I suggested,

“grotesquely improbable, no doubt, but still just conceivable? Might the whole story

of the cataleptic Russian and his son be a concoction of Dr. Trevelyan’s, who has,

for his own purposes, been in Blessington’s rooms?”

I saw in the gas-light that Holmes wore an amused smile at

this brilliant departure of mine. I saw in the gas-light that Holmes wore an amused smile at

this brilliant departure of mine.

“My dear fellow,” said he, “it was one of the

first solutions which occurred to me, but I was soon able to corroborate the doctor’s

tale. This young man has left prints upon the stair-carpet which made it quite superfluous

for me to ask to see those which he had made in the room. When I tell you that his shoes

were square-toed instead of being pointed like Blessington’s, and were quite an inch

and a [431] third longer

than the doctor’s, you will acknowledge that there can be no doubt as to his

individuality. But we may sleep on it now, for I shall be surprised if we do not hear

something further from Brook Street in the morning.” “My dear fellow,” said he, “it was one of the

first solutions which occurred to me, but I was soon able to corroborate the doctor’s

tale. This young man has left prints upon the stair-carpet which made it quite superfluous

for me to ask to see those which he had made in the room. When I tell you that his shoes

were square-toed instead of being pointed like Blessington’s, and were quite an inch

and a [431] third longer

than the doctor’s, you will acknowledge that there can be no doubt as to his

individuality. But we may sleep on it now, for I shall be surprised if we do not hear

something further from Brook Street in the morning.”

Sherlock Holmes’s prophecy was soon fulfilled, and in

a dramatic fashion. At half-past seven next morning, in the first dim glimmer of daylight,

I found him standing by my bedside in his dressing-gown. Sherlock Holmes’s prophecy was soon fulfilled, and in

a dramatic fashion. At half-past seven next morning, in the first dim glimmer of daylight,

I found him standing by my bedside in his dressing-gown.

“There’s a brougham waiting for us, Watson,”

said he. “There’s a brougham waiting for us, Watson,”

said he.

“What’s the matter, then?” “What’s the matter, then?”

“The Brook Street business.” “The Brook Street business.”

“Any fresh news?” “Any fresh news?”

“Tragic, but ambiguous,” said he, pulling up the

blind. “Look at this–a sheet from a notebook, with ‘For God’s sake

come at once. P. T.,’ scrawled upon it in pencil. Our friend, the doctor, was hard

put to it when he wrote this. Come along, my dear fellow, for it’s an urgent

call.” “Tragic, but ambiguous,” said he, pulling up the

blind. “Look at this–a sheet from a notebook, with ‘For God’s sake

come at once. P. T.,’ scrawled upon it in pencil. Our friend, the doctor, was hard

put to it when he wrote this. Come along, my dear fellow, for it’s an urgent

call.”

In a quarter of an hour or so we were back at the

physician’s house. He came running out to meet us with a face of horror. In a quarter of an hour or so we were back at the

physician’s house. He came running out to meet us with a face of horror.

“Oh, such a business!” he cried with his hands to

his temples. “Oh, such a business!” he cried with his hands to

his temples.

“What then?” “What then?”

“Blessington has committed suicide!” “Blessington has committed suicide!”

Holmes whistled. Holmes whistled.

“Yes, he hanged himself during the night.” “Yes, he hanged himself during the night.”

We had entered, and the doctor had preceded us into what was

evidently his waiting-room. We had entered, and the doctor had preceded us into what was

evidently his waiting-room.

“I really hardly know what I am doing,” he cried.

“The police are already upstairs. It has shaken me most dreadfully.” “I really hardly know what I am doing,” he cried.

“The police are already upstairs. It has shaken me most dreadfully.”

“When did you find it out?” “When did you find it out?”

“He has a cup of tea taken in to him early every morning.

When the maid entered, about seven, there the unfortunate fellow was hanging in the middle

of the room. He had tied his cord to the hook on which the heavy lamp used to hang, and he

had jumped off from the top of the very box that he showed us yesterday.” “He has a cup of tea taken in to him early every morning.

When the maid entered, about seven, there the unfortunate fellow was hanging in the middle

of the room. He had tied his cord to the hook on which the heavy lamp used to hang, and he

had jumped off from the top of the very box that he showed us yesterday.”

Holmes stood for a moment in deep thought. Holmes stood for a moment in deep thought.

“With your permission,” said he at last, “I

should like to go upstairs and look into the matter.” “With your permission,” said he at last, “I

should like to go upstairs and look into the matter.”

We both ascended, followed by the doctor. We both ascended, followed by the doctor.

It was a dreadful sight which met us as we entered the bedroom

door. I have spoken of the impression of flabbiness which this man Blessington conveyed.

As he dangled from the hook it was exaggerated and intensified until he was scarce human

in his appearance. The neck was drawn out like a plucked chicken’s, making the rest

of him seem the more obese and unnatural by the contrast. He was clad only in his long

night-dress, and his swollen ankles and ungainly feet protruded starkly from beneath it.

Beside him stood a smart-looking police-inspector, who was taking notes in a pocketbook. It was a dreadful sight which met us as we entered the bedroom

door. I have spoken of the impression of flabbiness which this man Blessington conveyed.

As he dangled from the hook it was exaggerated and intensified until he was scarce human

in his appearance. The neck was drawn out like a plucked chicken’s, making the rest

of him seem the more obese and unnatural by the contrast. He was clad only in his long

night-dress, and his swollen ankles and ungainly feet protruded starkly from beneath it.

Beside him stood a smart-looking police-inspector, who was taking notes in a pocketbook.

“Ah, Mr. Holmes,” said he heartily as my friend

entered, “I am delighted to see you.” “Ah, Mr. Holmes,” said he heartily as my friend

entered, “I am delighted to see you.”

“Good-morning, Lanner,” answered Holmes; “you

won’t think me an intruder, I am sure. Have you heard of the events which led up to

this affair?” “Good-morning, Lanner,” answered Holmes; “you

won’t think me an intruder, I am sure. Have you heard of the events which led up to

this affair?”

“Yes, I heard something of them.” “Yes, I heard something of them.”

[432] “Have

you formed any opinion?” [432] “Have

you formed any opinion?”

“As far as I can see, the man has been driven out of his

senses by fright. The bed has been well slept in, you see. There’s his impression,

deep enough. It’s about five in the morning, you know, that suicides are most common.

That would be about his time for hanging himself. It seems to have been a very deliberate

affair.” “As far as I can see, the man has been driven out of his

senses by fright. The bed has been well slept in, you see. There’s his impression,

deep enough. It’s about five in the morning, you know, that suicides are most common.

That would be about his time for hanging himself. It seems to have been a very deliberate

affair.”

“I should say that he has been dead about three hours,

judging by the rigidity of the muscles,” said I. “I should say that he has been dead about three hours,

judging by the rigidity of the muscles,” said I.

“Noticed anything peculiar about the room?” asked

Holmes. “Noticed anything peculiar about the room?” asked

Holmes.

“Found a screw-driver and some screws on the wash-hand

stand. Seems to have smoked heavily during the night, too. Here are four cigar-ends that I

picked out of the fireplace.” “Found a screw-driver and some screws on the wash-hand

stand. Seems to have smoked heavily during the night, too. Here are four cigar-ends that I

picked out of the fireplace.”

“Hum!” said Holmes, “have you got his

cigar-holder?” “Hum!” said Holmes, “have you got his

cigar-holder?”

“No, I have seen none.” “No, I have seen none.”

“His cigar-case, then?” “His cigar-case, then?”

“Yes, it was in his coat-pocket.” “Yes, it was in his coat-pocket.”

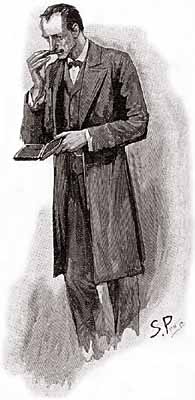

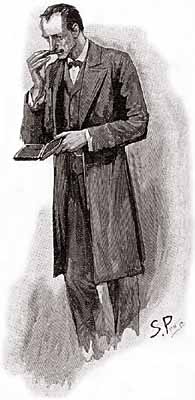

Holmes opened it and smelled the single cigar which it

contained. Holmes opened it and smelled the single cigar which it

contained.

“Oh, this is a Havana, and these others are cigars of

the peculiar sort which are imported by the Dutch from their East Indian colonies. They

are usually wrapped in straw, you know, and are thinner for their length than any other

brand.” He picked up the four ends and examined them with his pocket-lens. “Oh, this is a Havana, and these others are cigars of

the peculiar sort which are imported by the Dutch from their East Indian colonies. They

are usually wrapped in straw, you know, and are thinner for their length than any other

brand.” He picked up the four ends and examined them with his pocket-lens.

“Two of these have been smoked from a holder and two

without,” said he. “Two have been cut by a not very sharp knife, and two have

had the ends bitten off by a set of excellent teeth. This is no suicide, Mr. Lanner. It is

a very deeply planned and cold-blooded murder.” “Two of these have been smoked from a holder and two

without,” said he. “Two have been cut by a not very sharp knife, and two have

had the ends bitten off by a set of excellent teeth. This is no suicide, Mr. Lanner. It is

a very deeply planned and cold-blooded murder.”

“Impossible!” cried the inspector. “Impossible!” cried the inspector.

“And why?” “And why?”

“Why should anyone murder a man in so clumsy a fashion as

by hanging him?” “Why should anyone murder a man in so clumsy a fashion as

by hanging him?”

“That is what we have to find out.” “That is what we have to find out.”

“How could they get in?” “How could they get in?”

“Through the front door.” “Through the front door.”

“It was barred in the morning.” “It was barred in the morning.”

“Then it was barred after them.” “Then it was barred after them.”

“How do you know?” “How do you know?”

“I saw their traces. Excuse me a moment, and I may be

able to give you some further information about it.” “I saw their traces. Excuse me a moment, and I may be

able to give you some further information about it.”

He went over to the door, and turning the lock he examined it

in his methodical way. Then he took out the key, which was on the inside, and inspected

that also. The bed, the carpet, the chairs, the mantelpiece, the dead body, and the rope

were each in turn examined, until at last he professed himself satisfied, and with my aid

and that of the inspector cut down the wretched object and laid it reverently under a

sheet. He went over to the door, and turning the lock he examined it

in his methodical way. Then he took out the key, which was on the inside, and inspected

that also. The bed, the carpet, the chairs, the mantelpiece, the dead body, and the rope

were each in turn examined, until at last he professed himself satisfied, and with my aid

and that of the inspector cut down the wretched object and laid it reverently under a

sheet.

“How about this rope?” he asked. “How about this rope?” he asked.

“It is cut off this,” said Dr. Trevelyan, drawing a

large coil from under the bed. “He was morbidly nervous of fire, and always kept this

beside him, so that he might escape by the window in case the stairs were burning.” “It is cut off this,” said Dr. Trevelyan, drawing a

large coil from under the bed. “He was morbidly nervous of fire, and always kept this

beside him, so that he might escape by the window in case the stairs were burning.”

“That must have saved them trouble,” said Holmes

thoughtfully. “Yes, the actual facts are very plain, and I shall be surprised if by

the afternoon I cannot [433] give

you the reasons for them as well. I will take this photograph of Blessington, which I see

upon the mantelpiece, as it may help me in my inquiries.” “That must have saved them trouble,” said Holmes

thoughtfully. “Yes, the actual facts are very plain, and I shall be surprised if by

the afternoon I cannot [433] give

you the reasons for them as well. I will take this photograph of Blessington, which I see

upon the mantelpiece, as it may help me in my inquiries.”

“But you have told us nothing!” cried the doctor. “But you have told us nothing!” cried the doctor.

“Oh, there can be no doubt as to the sequence of

events,” said Holmes. “There were three of them in it: the young man, the old

man, and a third, to whose identity I have no clue. The first two, I need hardly remark,

are the same who masqueraded as the Russian count and his son, so we can give a very full

description of them. They were admitted by a confederate inside the house. If I might

offer you a word of advice, Inspector, it would be to arrest the page, who, as I

understand, has only recently come into your service, Doctor.” “Oh, there can be no doubt as to the sequence of

events,” said Holmes. “There were three of them in it: the young man, the old

man, and a third, to whose identity I have no clue. The first two, I need hardly remark,

are the same who masqueraded as the Russian count and his son, so we can give a very full

description of them. They were admitted by a confederate inside the house. If I might

offer you a word of advice, Inspector, it would be to arrest the page, who, as I

understand, has only recently come into your service, Doctor.”

“The young imp cannot be found,” said Dr. Trevelyan;

“the maid and the cook have just been searching for him.” “The young imp cannot be found,” said Dr. Trevelyan;

“the maid and the cook have just been searching for him.”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders. Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“He has played a not unimportant part in this

drama,” said he. “The three men having ascended the stairs, which they did on

tiptoe, the elder man first, the younger man second, and the unknown man in the rear–

–” “He has played a not unimportant part in this

drama,” said he. “The three men having ascended the stairs, which they did on

tiptoe, the elder man first, the younger man second, and the unknown man in the rear–

–”

“My dear Holmes!” I ejaculated. “My dear Holmes!” I ejaculated.

“Oh, there could be no question as to the superimposing

of the footmarks. I had the advantage of learning which was which last night. They

ascended, then, to Mr. Blessington’s room, the door of which they found to be locked.

With the help of a wire, however, they forced round the key. Even without the lens you

will perceive, by the scratches on this ward, where the pressure was applied. “Oh, there could be no question as to the superimposing

of the footmarks. I had the advantage of learning which was which last night. They

ascended, then, to Mr. Blessington’s room, the door of which they found to be locked.

With the help of a wire, however, they forced round the key. Even without the lens you

will perceive, by the scratches on this ward, where the pressure was applied.

“On entering the room their first proceeding must have

been to gag Mr. Blessington. He may have been asleep, or he may have been so paralyzed

with terror as to have been unable to cry out. These walls are thick, and it is

conceivable that his shriek, if he had time to utter one, was unheard. “On entering the room their first proceeding must have

been to gag Mr. Blessington. He may have been asleep, or he may have been so paralyzed

with terror as to have been unable to cry out. These walls are thick, and it is

conceivable that his shriek, if he had time to utter one, was unheard.

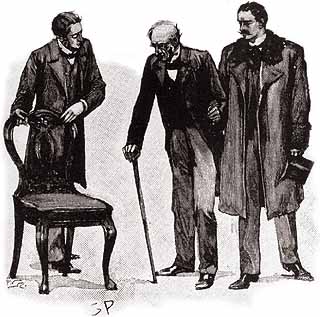

“Having secured him, it is evident to me that a

consultation of some sort was held. Probably it was something in the nature of a judicial

proceeding. It must have lasted for some time, for it was then that these cigars were

smoked. The older man sat in that wicker chair; it was he who used the cigar-holder. The

younger man sat over yonder; he knocked his ash off against the chest of drawers. The

third fellow paced up and down. Blessington, I think, sat upright in the bed, but of that

I cannot be absolutely certain. “Having secured him, it is evident to me that a

consultation of some sort was held. Probably it was something in the nature of a judicial

proceeding. It must have lasted for some time, for it was then that these cigars were

smoked. The older man sat in that wicker chair; it was he who used the cigar-holder. The

younger man sat over yonder; he knocked his ash off against the chest of drawers. The

third fellow paced up and down. Blessington, I think, sat upright in the bed, but of that

I cannot be absolutely certain.

“Well, it ended by their taking Blessington and

hanging him. The matter was so prearranged that it is my belief that they brought with

them some sort of block or pulley which might serve as a gallows. That screw-driver and

those screws were, as I conceive, for fixing it up. Seeing the hook, however, they

naturally saved themselves the trouble. Having finished their work they made off, and the

door was barred behind them by their confederate.” “Well, it ended by their taking Blessington and

hanging him. The matter was so prearranged that it is my belief that they brought with

them some sort of block or pulley which might serve as a gallows. That screw-driver and

those screws were, as I conceive, for fixing it up. Seeing the hook, however, they

naturally saved themselves the trouble. Having finished their work they made off, and the

door was barred behind them by their confederate.”

We had all listened with the deepest interest to this sketch

of the night’s doings, which Holmes had deduced from signs so subtle and minute that,

even when he had pointed them out to us, we could scarcely follow him in his reasonings.

The inspector hurried away on the instant to make inquiries about the page, while Holmes

and I returned to Baker Street for breakfast. We had all listened with the deepest interest to this sketch

of the night’s doings, which Holmes had deduced from signs so subtle and minute that,

even when he had pointed them out to us, we could scarcely follow him in his reasonings.

The inspector hurried away on the instant to make inquiries about the page, while Holmes

and I returned to Baker Street for breakfast.

“I’ll be back by three,” said he when we had

finished our meal. “Both the inspector and the doctor will meet me here at that hour,

and I hope by that time to have cleared up any little obscurity which the case may still

present.” “I’ll be back by three,” said he when we had

finished our meal. “Both the inspector and the doctor will meet me here at that hour,

and I hope by that time to have cleared up any little obscurity which the case may still

present.”

[434] Our

visitors arrived at the appointed time, but it was a quarter to four before my friend put

in an appearance. From his expression as he entered, however, I could see that all had

gone well with him. [434] Our

visitors arrived at the appointed time, but it was a quarter to four before my friend put

in an appearance. From his expression as he entered, however, I could see that all had

gone well with him.

“Any news, Inspector?” “Any news, Inspector?”

“We have got the boy, sir.” “We have got the boy, sir.”

“Excellent, and I have got the men.” “Excellent, and I have got the men.”

“You have got them!” we cried, all three. “You have got them!” we cried, all three.

“Well, at least I have got their identity. This so-called

Blessington is, as I expected, well known at headquarters, and so are his assailants.

Their names are Biddle, Hayward, and Moffat.” “Well, at least I have got their identity. This so-called

Blessington is, as I expected, well known at headquarters, and so are his assailants.

Their names are Biddle, Hayward, and Moffat.”

“The Worthingdon bank gang,” cried the inspector. “The Worthingdon bank gang,” cried the inspector.

“Precisely,” said Holmes. “Precisely,” said Holmes.

“Then Blessington must have been Sutton.” “Then Blessington must have been Sutton.”

“Exactly,” said Holmes. “Exactly,” said Holmes.

“Why, that makes it as clear as crystal,” said the

inspector. “Why, that makes it as clear as crystal,” said the

inspector.

But Trevelyan and I looked at each other in bewilderment. But Trevelyan and I looked at each other in bewilderment.

“You must surely remember the great Worthingdon bank

business,” said Holmes. “Five men were in it–these four and a fifth called

Cartwright. Tobin, the care-taker, was murdered, and the thieves got away with seven

thousand pounds. This was in 1875. They were all five arrested, but the evidence against

them was by no means conclusive. This Blessington or Sutton, who was the worst of the

gang, turned informer. On his evidence Cartwright was hanged and the other three got

fifteen years apiece. When they got out the other day, which was some years before their

full term, they set themselves, as you perceive, to hunt down the traitor and to avenge

the death of their comrade upon him. Twice they tried to get at him and failed; a third

time, you see, it came off. Is there anything further which I can explain, Dr.

Trevelyan?” “You must surely remember the great Worthingdon bank

business,” said Holmes. “Five men were in it–these four and a fifth called

Cartwright. Tobin, the care-taker, was murdered, and the thieves got away with seven

thousand pounds. This was in 1875. They were all five arrested, but the evidence against

them was by no means conclusive. This Blessington or Sutton, who was the worst of the

gang, turned informer. On his evidence Cartwright was hanged and the other three got

fifteen years apiece. When they got out the other day, which was some years before their

full term, they set themselves, as you perceive, to hunt down the traitor and to avenge

the death of their comrade upon him. Twice they tried to get at him and failed; a third

time, you see, it came off. Is there anything further which I can explain, Dr.

Trevelyan?”

“I think you have made it all remarkably clear,”

said the doctor. “No doubt the day on which he was so perturbed was the day when he

had seen of their release in the newspapers.” “I think you have made it all remarkably clear,”

said the doctor. “No doubt the day on which he was so perturbed was the day when he

had seen of their release in the newspapers.”

“Quite so. His talk about a burglary was the merest

blind.” “Quite so. His talk about a burglary was the merest

blind.”

“But why could he not tell you this?” “But why could he not tell you this?”

“Well, my dear sir, knowing the vindictive character of

his old associates, he was trying to hide his own identity from everybody as long as he

could. His secret was a shameful one, and he could not bring himself to divulge it.

However, wretch as he was, he was still living under the shield of British law, and I have

no doubt, Inspector, that you will see that, though that shield may fail to guard, the

sword of justice is still there to avenge.” “Well, my dear sir, knowing the vindictive character of

his old associates, he was trying to hide his own identity from everybody as long as he

could. His secret was a shameful one, and he could not bring himself to divulge it.

However, wretch as he was, he was still living under the shield of British law, and I have

no doubt, Inspector, that you will see that, though that shield may fail to guard, the

sword of justice is still there to avenge.”

Such were the singular circumstances in connection with the

Resident Patient and the Brook Street Doctor. From that night nothing has been seen of the

three murderers by the police, and it is surmised at Scotland Yard that they were among

the passengers of the ill-fated steamer Norah Creina, which was lost some years

ago with all hands upon the Portuguese coast, some leagues to the north of Oporto. The

proceedings against the page broke down for want of evidence, and the Brook Street

Mystery, as it was called, has never until now been fully dealt with in any public print. Such were the singular circumstances in connection with the

Resident Patient and the Brook Street Doctor. From that night nothing has been seen of the

three murderers by the police, and it is surmised at Scotland Yard that they were among

the passengers of the ill-fated steamer Norah Creina, which was lost some years

ago with all hands upon the Portuguese coast, some leagues to the north of Oporto. The

proceedings against the page broke down for want of evidence, and the Brook Street

Mystery, as it was called, has never until now been fully dealt with in any public print.

|

![]() It had been a close, rainy day in October. Our blinds were

half-drawn, and Holmes lay curled upon the sofa, reading and re-reading a letter which he

had [423] received by the

morning post. For myself, my term of service in India had trained me to stand heat better

than cold, and a thermometer of ninety was no hardship. But the paper was uninteresting.

Parliament had risen. Everybody was out of town, and I yearned for the glades of the New

Forest or the shingle of Southsea. A depleted bank account had caused me to postpone my

holiday, and as to my companion, neither the country nor the sea presented the slightest

attraction to him. He loved to lie in the very centre of five millions of people, with his

filaments stretching out and running through them, responsive to every little rumour or

suspicion of unsolved crime. Appreciation of nature found no place among his many gifts,

and his only change was when he turned his mind from the evil-doer of the town to track

down his brother of the country.

It had been a close, rainy day in October. Our blinds were

half-drawn, and Holmes lay curled upon the sofa, reading and re-reading a letter which he

had [423] received by the

morning post. For myself, my term of service in India had trained me to stand heat better

than cold, and a thermometer of ninety was no hardship. But the paper was uninteresting.

Parliament had risen. Everybody was out of town, and I yearned for the glades of the New

Forest or the shingle of Southsea. A depleted bank account had caused me to postpone my

holiday, and as to my companion, neither the country nor the sea presented the slightest

attraction to him. He loved to lie in the very centre of five millions of people, with his

filaments stretching out and running through them, responsive to every little rumour or

suspicion of unsolved crime. Appreciation of nature found no place among his many gifts,

and his only change was when he turned his mind from the evil-doer of the town to track

down his brother of the country.![]() Finding that Holmes was too absorbed for conversation, I had

tossed aside the barren paper, and, leaning back in my chair I fell into a brown study.

Suddenly my companion’s voice broke in upon my thoughts.

Finding that Holmes was too absorbed for conversation, I had

tossed aside the barren paper, and, leaning back in my chair I fell into a brown study.

Suddenly my companion’s voice broke in upon my thoughts.![]() “You are right, Watson,” said he. “It does seem

a very preposterous way of settling a dispute.”

“You are right, Watson,” said he. “It does seem

a very preposterous way of settling a dispute.”![]() “Most preposterous!” I exclaimed, and then, suddenly

realizing how he had echoed the inmost thought of my soul, I sat up in my chair and stared

at him in blank amazement.

“Most preposterous!” I exclaimed, and then, suddenly

realizing how he had echoed the inmost thought of my soul, I sat up in my chair and stared

at him in blank amazement.![]() “What is this, Holmes?” I cried. “This is

beyond anything which I could have imagined.”

“What is this, Holmes?” I cried. “This is

beyond anything which I could have imagined.”![]() He laughed heartily at my perplexity.

He laughed heartily at my perplexity.![]() “You remember,” said he, “that some little time

ago, when I read you the passage in one of Poe’s sketches, in which a close reasoner

follows the unspoken thoughts of his companion, you were inclined to treat the matter as a

mere tour de force of the author. On my remarking that I was constantly in the

habit of doing the same thing you expressed incredulity.”

“You remember,” said he, “that some little time

ago, when I read you the passage in one of Poe’s sketches, in which a close reasoner

follows the unspoken thoughts of his companion, you were inclined to treat the matter as a

mere tour de force of the author. On my remarking that I was constantly in the

habit of doing the same thing you expressed incredulity.”![]() “Oh, no!”

“Oh, no!”![]() “Perhaps not with your tongue, my dear Watson, but

certainly with your eyebrows. So when I saw you throw down your paper and enter upon a

train of thought, I was very happy to have the opportunity of reading it off, and

eventually of breaking into it, as a proof that I had been in rapport with you.”

“Perhaps not with your tongue, my dear Watson, but

certainly with your eyebrows. So when I saw you throw down your paper and enter upon a

train of thought, I was very happy to have the opportunity of reading it off, and

eventually of breaking into it, as a proof that I had been in rapport with you.”![]() But I was still far from satisfied. “In the example which

you read to me,” said I, “the reasoner drew his conclusions from the actions of

the man whom he observed. If I remember right, he stumbled over a heap of stones, looked

up at the stars, and so on. But I have been seated quietly in my chair, and what clues can

I have given you?”

But I was still far from satisfied. “In the example which

you read to me,” said I, “the reasoner drew his conclusions from the actions of

the man whom he observed. If I remember right, he stumbled over a heap of stones, looked

up at the stars, and so on. But I have been seated quietly in my chair, and what clues can

I have given you?”![]() “You do yourself an injustice. The features are given to

man as the means by which he shall express his emotions, and yours are faithful

servants.”

“You do yourself an injustice. The features are given to

man as the means by which he shall express his emotions, and yours are faithful

servants.”![]() “Do you mean to say that you read my train of thoughts

from my features?”

“Do you mean to say that you read my train of thoughts

from my features?”![]() “Your features, and especially your eyes. Perhaps you

cannot yourself recall how your reverie commenced?”

“Your features, and especially your eyes. Perhaps you

cannot yourself recall how your reverie commenced?”![]() “No, I cannot.”

“No, I cannot.”![]() “Then I will tell you. After throwing down your paper,

which was the action which drew my attention to you, you sat for half a minute with a

vacant expression. Then your eyes fixed themselves upon your newly framed picture of

General Gordon, and I saw by the alteration in your face that a train of thought had been

started. But it did not lead very far. Your eyes turned across to the unframed portrait of

Henry Ward Beecher, which stands upon the top of your books. You then [424] glanced up at the wall, and

of course your meaning was obvious. You were thinking that if the portrait were framed it

would just cover that bare space and correspond with Gordon’s picture over

there.”

“Then I will tell you. After throwing down your paper,

which was the action which drew my attention to you, you sat for half a minute with a

vacant expression. Then your eyes fixed themselves upon your newly framed picture of

General Gordon, and I saw by the alteration in your face that a train of thought had been

started. But it did not lead very far. Your eyes turned across to the unframed portrait of

Henry Ward Beecher, which stands upon the top of your books. You then [424] glanced up at the wall, and

of course your meaning was obvious. You were thinking that if the portrait were framed it

would just cover that bare space and correspond with Gordon’s picture over

there.”![]() “You have followed me wonderfully!” I exclaimed.

“You have followed me wonderfully!” I exclaimed.![]() “So far I could hardly have gone astray. But now your

thoughts went back to Beecher, and you looked hard across as if you were studying the

character in his features. Then your eyes ceased to pucker, but you continued to look

across, and your face was thoughtful. You were recalling the incidents of Beecher’s