|

|

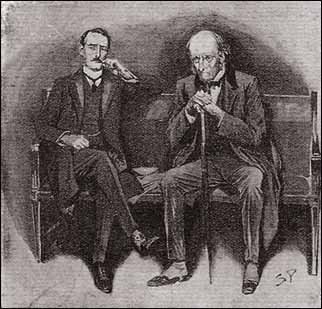

The Premier sprang to his feet with that quick, fierce gleam

of his deep-set eyes before which a Cabinet has cowered. “I am not accustomed, sir,

” he began, but mastered his anger and resumed his seat. For a minute or more we all

sat in silence. Then the old statesman shrugged his shoulders. The Premier sprang to his feet with that quick, fierce gleam

of his deep-set eyes before which a Cabinet has cowered. “I am not accustomed, sir,

” he began, but mastered his anger and resumed his seat. For a minute or more we all

sat in silence. Then the old statesman shrugged his shoulders.

“We must accept your terms, Mr. Holmes. No doubt you are

right, and it is unreasonable for us to expect you to act unless we give you our entire

confidence.” “We must accept your terms, Mr. Holmes. No doubt you are

right, and it is unreasonable for us to expect you to act unless we give you our entire

confidence.”

[653] “I

agree with you,” said the younger statesman. [653] “I

agree with you,” said the younger statesman.

“Then I will tell you, relying entirely upon your honour

and that of your colleague, Dr. Watson. I may appeal to your patriotism also, for I could

not imagine a greater misfortune for the country than that this affair should come

out.” “Then I will tell you, relying entirely upon your honour

and that of your colleague, Dr. Watson. I may appeal to your patriotism also, for I could

not imagine a greater misfortune for the country than that this affair should come

out.”

“You may safely trust us.” “You may safely trust us.”

“The letter, then, is from a certain foreign potentate

who has been ruffled by some recent Colonial developments of this country. It has been

written hurriedly and upon his own responsibility entirely. Inquiries have shown that his

Ministers know nothing of the matter. At the same time it is couched in so unfortunate a

manner, and certain phrases in it are of so provocative a character, that its publication

would undoubtedly lead to a most dangerous state of feeling in this country. There would

be such a ferment, sir, that I do not hesitate to say that within a week of the

publication of that letter this country would be involved in a great war.” “The letter, then, is from a certain foreign potentate

who has been ruffled by some recent Colonial developments of this country. It has been

written hurriedly and upon his own responsibility entirely. Inquiries have shown that his

Ministers know nothing of the matter. At the same time it is couched in so unfortunate a

manner, and certain phrases in it are of so provocative a character, that its publication

would undoubtedly lead to a most dangerous state of feeling in this country. There would

be such a ferment, sir, that I do not hesitate to say that within a week of the

publication of that letter this country would be involved in a great war.”

Holmes wrote a name upon a slip of paper and handed it to the

Premier. Holmes wrote a name upon a slip of paper and handed it to the

Premier.

“Exactly. It was he. And it is this letter–this

letter which may well mean the expenditure of a thousand millions and the lives of a

hundred thousand men–which has become lost in this unaccountable fashion.” “Exactly. It was he. And it is this letter–this

letter which may well mean the expenditure of a thousand millions and the lives of a

hundred thousand men–which has become lost in this unaccountable fashion.”

“Have you informed the sender?” “Have you informed the sender?”

“Yes, sir, a cipher telegram has been despatched.” “Yes, sir, a cipher telegram has been despatched.”

“Perhaps he desires the publication of the letter.” “Perhaps he desires the publication of the letter.”

“No, sir, we have strong reason to believe that he

already understands that he has acted in an indiscreet and hot-headed manner. It would be

a greater blow to him and to his country than to us if this letter were to come out.” “No, sir, we have strong reason to believe that he

already understands that he has acted in an indiscreet and hot-headed manner. It would be

a greater blow to him and to his country than to us if this letter were to come out.”

“If this is so, whose interest is it that the letter

should come out? Why should anyone desire to steal it or to publish it?” “If this is so, whose interest is it that the letter

should come out? Why should anyone desire to steal it or to publish it?”

“There, Mr. Holmes, you take me into regions of high

international politics. But if you consider the European situation you will have no

difficulty in perceiving the motive. The whole of Europe is an armed camp. There is a

double league which makes a fair balance of military power. Great Britain holds the

scales. If Britain were driven into war with one confederacy, it would assure the

supremacy of the other confederacy, whether they joined in the war or not. Do you

follow?” “There, Mr. Holmes, you take me into regions of high

international politics. But if you consider the European situation you will have no

difficulty in perceiving the motive. The whole of Europe is an armed camp. There is a

double league which makes a fair balance of military power. Great Britain holds the

scales. If Britain were driven into war with one confederacy, it would assure the

supremacy of the other confederacy, whether they joined in the war or not. Do you

follow?”

“Very clearly. It is then the interest of the enemies of

this potentate to secure and publish this letter, so as to make a breach between his

country and ours?” “Very clearly. It is then the interest of the enemies of

this potentate to secure and publish this letter, so as to make a breach between his

country and ours?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“And to whom would this document be sent if it fell into

the hands of an enemy?” “And to whom would this document be sent if it fell into

the hands of an enemy?”

“To any of the great Chancelleries of Europe. It is

probably speeding on its way thither at the present instant as fast as steam can take

it.” “To any of the great Chancelleries of Europe. It is

probably speeding on its way thither at the present instant as fast as steam can take

it.”

Mr. Trelawney Hope dropped his head on his chest and groaned

aloud. The Premier placed his hand kindly upon his shoulder. Mr. Trelawney Hope dropped his head on his chest and groaned

aloud. The Premier placed his hand kindly upon his shoulder.

“It is your misfortune, my dear fellow. No one can blame

you. There is no precaution which you have neglected. Now, Mr. Holmes, you are in full

possession of the facts. What course do you recommend?” “It is your misfortune, my dear fellow. No one can blame

you. There is no precaution which you have neglected. Now, Mr. Holmes, you are in full

possession of the facts. What course do you recommend?”

Holmes shook his head mournfully. Holmes shook his head mournfully.

“You think, sir, that unless this document is recovered

there will be war?” “You think, sir, that unless this document is recovered

there will be war?”

“I think it is very probable.” “I think it is very probable.”

“Then, sir, prepare for war.” “Then, sir, prepare for war.”

“That is a hard saying, Mr. Holmes.” “That is a hard saying, Mr. Holmes.”

“Consider the facts, sir. It is inconceivable that it was

taken after eleven-thirty [654] at

night, since I understand that Mr. Hope and his wife were both in the room from that hour

until the loss was found out. It was taken, then, yesterday evening between seven-thirty

and eleven-thirty, probably near the earlier hour, since whoever took it evidently knew

that it was there and would naturally secure it as early as possible. Now, sir, if a

document of this importance were taken at that hour, where can it be now? No one has any

reason to retain it. It has been passed rapidly on to those who need it. What chance have

we now to overtake or even to trace it? It is beyond our reach.” “Consider the facts, sir. It is inconceivable that it was

taken after eleven-thirty [654] at

night, since I understand that Mr. Hope and his wife were both in the room from that hour

until the loss was found out. It was taken, then, yesterday evening between seven-thirty

and eleven-thirty, probably near the earlier hour, since whoever took it evidently knew

that it was there and would naturally secure it as early as possible. Now, sir, if a

document of this importance were taken at that hour, where can it be now? No one has any

reason to retain it. It has been passed rapidly on to those who need it. What chance have

we now to overtake or even to trace it? It is beyond our reach.”

The Prime Minister rose from the settee. The Prime Minister rose from the settee.

“What you say is perfectly logical, Mr. Holmes. I feel

that the matter is indeed out of our hands.” “What you say is perfectly logical, Mr. Holmes. I feel

that the matter is indeed out of our hands.”

“Let us presume, for argument’s sake, that the

document was taken by the maid or by the valet– –” “Let us presume, for argument’s sake, that the

document was taken by the maid or by the valet– –”

“They are both old and tried servants.” “They are both old and tried servants.”

“I understand you to say that your room is on the second

floor, that there is no entrance from without, and that from within no one could go up

unobserved. It must, then, be somebody in the house who has taken it. To whom would the

thief take it? To one of several international spies and secret agents, whose names are

tolerably familiar to me. There are three who may be said to be the heads of their

profession. I will begin my research by going round and finding if each of them is at his

post. If one is missing–especially if he has disappeared since last night–we

will have some indication as to where the document has gone.” “I understand you to say that your room is on the second

floor, that there is no entrance from without, and that from within no one could go up

unobserved. It must, then, be somebody in the house who has taken it. To whom would the

thief take it? To one of several international spies and secret agents, whose names are

tolerably familiar to me. There are three who may be said to be the heads of their

profession. I will begin my research by going round and finding if each of them is at his

post. If one is missing–especially if he has disappeared since last night–we

will have some indication as to where the document has gone.”

“Why should he be missing?” asked the European

Secretary. “He would take the letter to an Embassy in London, as likely as not.” “Why should he be missing?” asked the European

Secretary. “He would take the letter to an Embassy in London, as likely as not.”

“I fancy not. These agents work independently, and their

relations with the Embassies are often strained.” “I fancy not. These agents work independently, and their

relations with the Embassies are often strained.”

The Prime Minister nodded his acquiescence. The Prime Minister nodded his acquiescence.

“I believe you are right, Mr. Holmes. He would take so

valuable a prize to headquarters with his own hands. I think that your course of action is

an excellent one. Meanwhile, Hope, we cannot neglect all our other duties on account of

this one misfortune. Should there be any fresh developments during the day we shall

communicate with you, and you will no doubt let us know the results of your own

inquiries.” “I believe you are right, Mr. Holmes. He would take so

valuable a prize to headquarters with his own hands. I think that your course of action is

an excellent one. Meanwhile, Hope, we cannot neglect all our other duties on account of

this one misfortune. Should there be any fresh developments during the day we shall

communicate with you, and you will no doubt let us know the results of your own

inquiries.”

The two statesmen bowed and walked gravely from the room. The two statesmen bowed and walked gravely from the room.

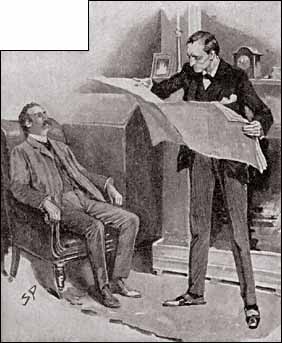

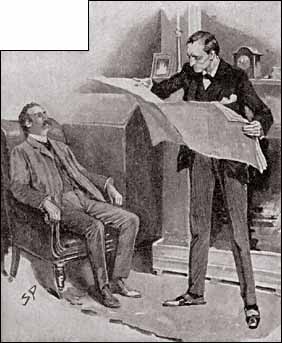

When our illustrious visitors had departed Holmes lit his pipe

in silence and sat for some time lost in the deepest thought. I had opened the morning

paper and was immersed in a sensational crime which had occurred in London the night

before, when my friend gave an exclamation, sprang to his feet, and laid his pipe down

upon the mantelpiece. When our illustrious visitors had departed Holmes lit his pipe

in silence and sat for some time lost in the deepest thought. I had opened the morning

paper and was immersed in a sensational crime which had occurred in London the night

before, when my friend gave an exclamation, sprang to his feet, and laid his pipe down

upon the mantelpiece.

“Yes,” said he, “there is no better way of

approaching it. The situation is desperate, but not hopeless. Even now, if we could be

sure which of them has taken it, it is just possible that it has not yet passed out of his

hands. After all, it is a question of money with these fellows, and I have the British

treasury behind me. If it’s on the market I’ll buy it–if it means another

penny on the income-tax. It is conceivable that the fellow might hold it back to see what

bids come from this side before he tries his luck on the other. There are only those three

capable of playing so bold a game–there are Oberstein, La Rothiere, and Eduardo

Lucas. I will see each of them.” “Yes,” said he, “there is no better way of

approaching it. The situation is desperate, but not hopeless. Even now, if we could be

sure which of them has taken it, it is just possible that it has not yet passed out of his

hands. After all, it is a question of money with these fellows, and I have the British

treasury behind me. If it’s on the market I’ll buy it–if it means another

penny on the income-tax. It is conceivable that the fellow might hold it back to see what

bids come from this side before he tries his luck on the other. There are only those three

capable of playing so bold a game–there are Oberstein, La Rothiere, and Eduardo

Lucas. I will see each of them.”

I glanced at my morning paper. I glanced at my morning paper.

[655] “Is

that Eduardo Lucas of Godolphin Street?” [655] “Is

that Eduardo Lucas of Godolphin Street?”

“Yes.” “Yes.”

“You will not see him.” “You will not see him.”

“Why not?” “Why not?”

“He was murdered in his house last night.” “He was murdered in his house last night.”

My friend has so often astonished me in the course of our

adventures that it was with a sense of exultation that I realized how completely I had

astonished him. He stared in amazement, and then snatched the paper from my hands. This

was the paragraph which I had been engaged in reading when he rose from his chair. My friend has so often astonished me in the course of our

adventures that it was with a sense of exultation that I realized how completely I had

astonished him. He stared in amazement, and then snatched the paper from my hands. This

was the paragraph which I had been engaged in reading when he rose from his chair.

MURDER IN WESTMINSTER

A crime of mysterious character was committed last night at

16 Godolphin Street, one of the old-fashioned and secluded rows of eighteenth century

houses which lie between the river and the Abbey, almost in the shadow of the great Tower

of the Houses of Parliament. This small but select mansion has been inhabited for some

years by Mr. Eduardo Lucas, well known in society circles both on account of his charming

personality and because he has the well-deserved reputation of being one of the best

amateur tenors in the country. Mr. Lucas is an unmarried man, thirty-four years of age,

and his establishment consists of Mrs. Pringle, an elderly housekeeper, and of Mitton, his

valet. The former retires early and sleeps at the top of the house. The valet was out for

the evening, visiting a friend at Hammersmith. From ten o’clock onward Mr. Lucas had

the house to himself. What occurred during that time has not yet transpired, but at a

quarter to twelve Police-constable Barrett, passing along Godolphin Street, observed that

the door of No. 16 was ajar. He knocked, but received no answer. Perceiving a light in the

front room, he advanced into the passage and again knocked, but without reply. He then

pushed open the door and entered. The room was in a state of wild disorder, the furniture

being all swept to one side, and one chair lying on its back in the centre. Beside this

chair, and still grasping one of its legs, lay the unfortunate tenant of the house. He had

been stabbed to the heart and must have died instantly. The knife with which the crime had

been committed was a curved Indian dagger, plucked down from a trophy of Oriental arms

which adorned one of the walls. Robbery does not appear to have been the motive of the

crime, for there had been no attempt to remove the valuable contents of the room. Mr.

Eduardo Lucas was so well known and popular that his violent and mysterious fate will

arouse painful interest and intense sympathy in a widespread circle of friends. A crime of mysterious character was committed last night at

16 Godolphin Street, one of the old-fashioned and secluded rows of eighteenth century

houses which lie between the river and the Abbey, almost in the shadow of the great Tower

of the Houses of Parliament. This small but select mansion has been inhabited for some

years by Mr. Eduardo Lucas, well known in society circles both on account of his charming

personality and because he has the well-deserved reputation of being one of the best

amateur tenors in the country. Mr. Lucas is an unmarried man, thirty-four years of age,

and his establishment consists of Mrs. Pringle, an elderly housekeeper, and of Mitton, his

valet. The former retires early and sleeps at the top of the house. The valet was out for

the evening, visiting a friend at Hammersmith. From ten o’clock onward Mr. Lucas had

the house to himself. What occurred during that time has not yet transpired, but at a

quarter to twelve Police-constable Barrett, passing along Godolphin Street, observed that

the door of No. 16 was ajar. He knocked, but received no answer. Perceiving a light in the

front room, he advanced into the passage and again knocked, but without reply. He then

pushed open the door and entered. The room was in a state of wild disorder, the furniture

being all swept to one side, and one chair lying on its back in the centre. Beside this

chair, and still grasping one of its legs, lay the unfortunate tenant of the house. He had

been stabbed to the heart and must have died instantly. The knife with which the crime had

been committed was a curved Indian dagger, plucked down from a trophy of Oriental arms

which adorned one of the walls. Robbery does not appear to have been the motive of the

crime, for there had been no attempt to remove the valuable contents of the room. Mr.

Eduardo Lucas was so well known and popular that his violent and mysterious fate will

arouse painful interest and intense sympathy in a widespread circle of friends.

“Well, Watson, what do you make of this?” asked

Holmes, after a long pause. “Well, Watson, what do you make of this?” asked

Holmes, after a long pause.

“It is an amazing coincidence.” “It is an amazing coincidence.”

“A coincidence! Here is one of the three men whom we

had named as possible actors in this drama, and he meets a violent death during the very

hours when we know that that drama was being enacted. The odds are enormous against its

being coincidence. No figures could express them. No, my dear Watson, the two events are

connected–must be connected. It is for us to find the connection.” “A coincidence! Here is one of the three men whom we

had named as possible actors in this drama, and he meets a violent death during the very

hours when we know that that drama was being enacted. The odds are enormous against its

being coincidence. No figures could express them. No, my dear Watson, the two events are

connected–must be connected. It is for us to find the connection.”

“But now the official police must know all.” “But now the official police must know all.”

“Not at all. They know all they see at Godolphin Street.

They know–and shall [656] know–nothing

of Whitehall Terrace. Only we know of both events, and can trace the relation

between them. There is one obvious point which would, in any case, have turned my

suspicions against Lucas. Godolphin Street, Westminster, is only a few minutes’ walk

from Whitehall Terrace. The other secret agents whom I have named live in the extreme West

End. It was easier, therefore, for Lucas than for the others to establish a connection or

receive a message from the European Secretary’s household–a small thing, and yet

where events are compressed into a few hours it may prove essential. Halloa! what have we

here?” “Not at all. They know all they see at Godolphin Street.

They know–and shall [656] know–nothing

of Whitehall Terrace. Only we know of both events, and can trace the relation

between them. There is one obvious point which would, in any case, have turned my

suspicions against Lucas. Godolphin Street, Westminster, is only a few minutes’ walk

from Whitehall Terrace. The other secret agents whom I have named live in the extreme West

End. It was easier, therefore, for Lucas than for the others to establish a connection or

receive a message from the European Secretary’s household–a small thing, and yet

where events are compressed into a few hours it may prove essential. Halloa! what have we

here?”

Mrs. Hudson had appeared with a lady’s card upon her

salver. Holmes glanced at it, raised his eyebrows, and handed it over to me. Mrs. Hudson had appeared with a lady’s card upon her

salver. Holmes glanced at it, raised his eyebrows, and handed it over to me.

“Ask Lady Hilda Trelawney Hope if she will be kind enough

to step up,” said he. “Ask Lady Hilda Trelawney Hope if she will be kind enough

to step up,” said he.

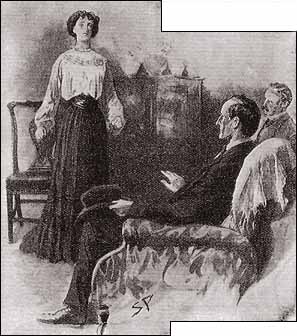

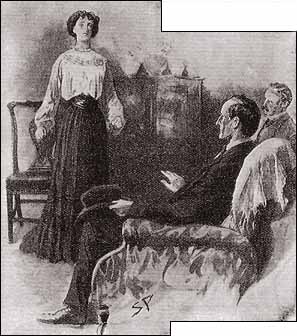

A moment later our modest apartment, already so

distinguished that morning, was further honoured by the entrance of the most lovely woman

in London. I had often heard of the beauty of the youngest daughter of the Duke of

Belminster, but no description of it, and no contemplation of colourless photographs, had

prepared me for the subtle, delicate charm and the beautiful colouring of that exquisite

head. And yet as we saw it that autumn morning, it was not its beauty which would be the

first thing to impress the observer. The cheek was lovely but it was paled with emotion,

the eyes were bright, but it was the brightness of fever, the sensitive mouth was tight

and drawn in an effort after self-command. Terror–not beauty–was what sprang

first to the eye as our fair visitor stood framed for an instant in the open door. A moment later our modest apartment, already so

distinguished that morning, was further honoured by the entrance of the most lovely woman

in London. I had often heard of the beauty of the youngest daughter of the Duke of

Belminster, but no description of it, and no contemplation of colourless photographs, had

prepared me for the subtle, delicate charm and the beautiful colouring of that exquisite

head. And yet as we saw it that autumn morning, it was not its beauty which would be the

first thing to impress the observer. The cheek was lovely but it was paled with emotion,

the eyes were bright, but it was the brightness of fever, the sensitive mouth was tight

and drawn in an effort after self-command. Terror–not beauty–was what sprang

first to the eye as our fair visitor stood framed for an instant in the open door.

“Has my husband been here, Mr. Holmes?” “Has my husband been here, Mr. Holmes?”

“Yes, madam, he has been here.” “Yes, madam, he has been here.”

“Mr. Holmes, I implore you not to tell him that I came

here.” Holmes bowed coldly, and motioned the lady to a chair. “Mr. Holmes, I implore you not to tell him that I came

here.” Holmes bowed coldly, and motioned the lady to a chair.

“Your ladyship places me in a very delicate position. I

beg that you will sit down and tell me what you desire, but I fear that I cannot make any

unconditional promise.” “Your ladyship places me in a very delicate position. I

beg that you will sit down and tell me what you desire, but I fear that I cannot make any

unconditional promise.”

She swept across the room and seated herself with her back to

the window. It was a queenly presence–tall, graceful, and intensely womanly. She swept across the room and seated herself with her back to

the window. It was a queenly presence–tall, graceful, and intensely womanly.

“Mr. Holmes,” she said–and her white-gloved

hands clasped and unclasped as she spoke–“I will speak frankly to you in the

hopes that it may induce you to speak frankly in return. There is complete confidence

between my husband and me on all matters save one. That one is politics. On this his lips

are sealed. He tells me nothing. Now, I am aware that there was a most deplorable

occurrence in our house last night. I know that a paper has disappeared. But because the

matter is political my husband refuses to take me into his complete confidence. Now it is

essential–essential, I say–that I should thoroughly understand it. You are the

only other person, save only these politicians, who knows the true facts. I beg you then,

Mr. Holmes, to tell me exactly what has happened and what it will lead to. Tell me all,

Mr. Holmes. Let no regard for your client’s interests keep you silent, for I assure

you that his interests, if he would only see it, would be best served by taking me into

his complete confidence. What was this paper which was stolen?” “Mr. Holmes,” she said–and her white-gloved

hands clasped and unclasped as she spoke–“I will speak frankly to you in the

hopes that it may induce you to speak frankly in return. There is complete confidence

between my husband and me on all matters save one. That one is politics. On this his lips

are sealed. He tells me nothing. Now, I am aware that there was a most deplorable

occurrence in our house last night. I know that a paper has disappeared. But because the

matter is political my husband refuses to take me into his complete confidence. Now it is

essential–essential, I say–that I should thoroughly understand it. You are the

only other person, save only these politicians, who knows the true facts. I beg you then,

Mr. Holmes, to tell me exactly what has happened and what it will lead to. Tell me all,

Mr. Holmes. Let no regard for your client’s interests keep you silent, for I assure

you that his interests, if he would only see it, would be best served by taking me into

his complete confidence. What was this paper which was stolen?”

“Madam, what you ask me is really impossible.” “Madam, what you ask me is really impossible.”

She groaned and sank her face in her hands. She groaned and sank her face in her hands.

“You must see that this is so, madam. If your husband

thinks fit to keep you in the dark over this matter, is it for me, who has only learned

the true facts under [657] the

pledge of professional secrecy, to tell what he has withheld? It is not fair to ask it. It

is him whom you must ask.” “You must see that this is so, madam. If your husband

thinks fit to keep you in the dark over this matter, is it for me, who has only learned

the true facts under [657] the

pledge of professional secrecy, to tell what he has withheld? It is not fair to ask it. It

is him whom you must ask.”

“I have asked him. I come to you as a last resource. But

without your telling me anything definite, Mr. Holmes, you may do a great service if you

would enlighten me on one point.” “I have asked him. I come to you as a last resource. But

without your telling me anything definite, Mr. Holmes, you may do a great service if you

would enlighten me on one point.”

“What is it, madam?” “What is it, madam?”

“Is my husband’s political career likely to suffer

through this incident?” “Is my husband’s political career likely to suffer

through this incident?”

“Well, madam, unless it is set right it may certainly

have a very unfortunate effect.” “Well, madam, unless it is set right it may certainly

have a very unfortunate effect.”

“Ah!” She drew in her breath sharply as one whose

doubts are resolved. “Ah!” She drew in her breath sharply as one whose

doubts are resolved.

“One more question, Mr. Holmes. From an expression which

my husband dropped in the first shock of this disaster I understood that terrible public

consequences might arise from the loss of this document.” “One more question, Mr. Holmes. From an expression which

my husband dropped in the first shock of this disaster I understood that terrible public

consequences might arise from the loss of this document.”

“If he said so, I certainly cannot deny it.” “If he said so, I certainly cannot deny it.”

“Of what nature are they?” “Of what nature are they?”

“Nay, madam, there again you ask me more than I can

possibly answer.” “Nay, madam, there again you ask me more than I can

possibly answer.”

“Then I will take up no more of your time. I cannot blame

you, Mr. Holmes, for having refused to speak more freely, and you on your side will not, I

am sure, think the worse of me because I desire, even against his will, to share my

husband’s anxieties. Once more I beg that you will say nothing of my visit.” “Then I will take up no more of your time. I cannot blame

you, Mr. Holmes, for having refused to speak more freely, and you on your side will not, I

am sure, think the worse of me because I desire, even against his will, to share my

husband’s anxieties. Once more I beg that you will say nothing of my visit.”

She looked back at us from the door, and I had a last

impression of that beautiful haunted face, the startled eyes, and the drawn mouth. Then

she was gone. She looked back at us from the door, and I had a last

impression of that beautiful haunted face, the startled eyes, and the drawn mouth. Then

she was gone.

“Now, Watson, the fair sex is your department,” said

Holmes, with a smile, when the dwindling frou-frou of skirts had ended in the slam of the

front door. “What was the fair lady’s game? What did she really want?” “Now, Watson, the fair sex is your department,” said

Holmes, with a smile, when the dwindling frou-frou of skirts had ended in the slam of the

front door. “What was the fair lady’s game? What did she really want?”

“Surely her own statement is clear and her anxiety very

natural.” “Surely her own statement is clear and her anxiety very

natural.”

“Hum! Think of her appearance, Watson–her manner,

her suppressed excitement, her restlessness, her tenacity in asking questions. Remember

that she comes of a caste who do not lightly show emotion.” “Hum! Think of her appearance, Watson–her manner,

her suppressed excitement, her restlessness, her tenacity in asking questions. Remember

that she comes of a caste who do not lightly show emotion.”

“She was certainly much moved.” “She was certainly much moved.”

“Remember also the curious earnestness with which she

assured us that it was best for her husband that she should know all. What did she mean by

that? And you must have observed, Watson, how she manoeuvred to have the light at her

back. She did not wish us to read her expression.” “Remember also the curious earnestness with which she

assured us that it was best for her husband that she should know all. What did she mean by

that? And you must have observed, Watson, how she manoeuvred to have the light at her

back. She did not wish us to read her expression.”

“Yes, she chose the one chair in the room.” “Yes, she chose the one chair in the room.”

“And yet the motives of women are so inscrutable. You

remember the woman at Margate whom I suspected for the same reason. No powder on her

nose–that proved to be the correct solution. How can you build on such a quicksand?

Their most trivial action may mean volumes, or their most extraordinary conduct may depend

upon a hairpin or a curling tongs. Good-morning, Watson.” “And yet the motives of women are so inscrutable. You

remember the woman at Margate whom I suspected for the same reason. No powder on her

nose–that proved to be the correct solution. How can you build on such a quicksand?

Their most trivial action may mean volumes, or their most extraordinary conduct may depend

upon a hairpin or a curling tongs. Good-morning, Watson.”

“You are off?” “You are off?”

“Yes, I will while away the morning at Godolphin Street

with our friends of the regular establishment. With Eduardo Lucas lies the solution of our

problem, though I must admit that I have not an inkling as to what form it may take. It is

a capital mistake to theorize in advance of the facts. Do you stay on guard, my good

Watson, and receive any fresh visitors. I’ll join you at lunch if I am able.” “Yes, I will while away the morning at Godolphin Street

with our friends of the regular establishment. With Eduardo Lucas lies the solution of our

problem, though I must admit that I have not an inkling as to what form it may take. It is

a capital mistake to theorize in advance of the facts. Do you stay on guard, my good

Watson, and receive any fresh visitors. I’ll join you at lunch if I am able.”

All that day and the next and the next Holmes was in a mood

which his friends would call taciturn, and others morose. He ran out and ran in, smoked

incessantly, played snatches on his violin, sank into reveries, devoured sandwiches at

irregular [658] hours, and

hardly answered the casual questions which I put to him. It was evident to me that things

were not going well with him or his quest. He would say nothing of the case, and it was

from the papers that I learned the particulars of the inquest, and the arrest with the

subsequent release of John Mitton, the valet of the deceased. The coroner’s jury

brought in the obvious Wilful Murder, but the parties remained as unknown as ever. No

motive was suggested. The room was full of articles of value, but none had been taken. The

dead man’s papers had not been tampered with. They were carefully examined, and

showed that he was a keen student of international politics, an indefatigable gossip, a

remarkable linguist, and an untiring letter writer. He had been on intimate terms with the

leading politicians of several countries. But nothing sensational was discovered among the

documents which filled his drawers. As to his relations with women, they appeared to have

been promiscuous but superficial. He had many acquaintances among them, but few friends,

and no one whom he loved. His habits were regular, his conduct inoffensive. His death was

an absolute mystery and likely to remain so. All that day and the next and the next Holmes was in a mood

which his friends would call taciturn, and others morose. He ran out and ran in, smoked

incessantly, played snatches on his violin, sank into reveries, devoured sandwiches at

irregular [658] hours, and

hardly answered the casual questions which I put to him. It was evident to me that things

were not going well with him or his quest. He would say nothing of the case, and it was

from the papers that I learned the particulars of the inquest, and the arrest with the

subsequent release of John Mitton, the valet of the deceased. The coroner’s jury

brought in the obvious Wilful Murder, but the parties remained as unknown as ever. No

motive was suggested. The room was full of articles of value, but none had been taken. The

dead man’s papers had not been tampered with. They were carefully examined, and

showed that he was a keen student of international politics, an indefatigable gossip, a

remarkable linguist, and an untiring letter writer. He had been on intimate terms with the

leading politicians of several countries. But nothing sensational was discovered among the

documents which filled his drawers. As to his relations with women, they appeared to have

been promiscuous but superficial. He had many acquaintances among them, but few friends,

and no one whom he loved. His habits were regular, his conduct inoffensive. His death was

an absolute mystery and likely to remain so.

As to the arrest of John Mitton, the valet, it was a council

of despair as an alternative to absolute inaction. But no case could be sustained against

him. He had visited friends in Hammersmith that night. The alibi was complete. It

is true that he started home at an hour which should have brought him to Westminster

before the time when the crime was discovered, but his own explanation that he had walked

part of the way seemed probable enough in view of the fineness of the night. He had

actually arrived at twelve o’clock, and appeared to be overwhelmed by the unexpected

tragedy. He had always been on good terms with his master. Several of the dead man’s

possessions–notably a small case of razors–had been found in the valet’s

boxes, but he explained that they had been presents from the deceased, and the housekeeper

was able to corroborate the story. Mitton had been in Lucas’s employment for three

years. It was noticeable that Lucas did not take Mitton on the Continent with him.

Sometimes he visited Paris for three months on end, but Mitton was left in charge of the

Godolphin Street house. As to the housekeeper, she had heard nothing on the night of the

crime. If her master had a visitor he had himself admitted him. As to the arrest of John Mitton, the valet, it was a council

of despair as an alternative to absolute inaction. But no case could be sustained against

him. He had visited friends in Hammersmith that night. The alibi was complete. It

is true that he started home at an hour which should have brought him to Westminster

before the time when the crime was discovered, but his own explanation that he had walked

part of the way seemed probable enough in view of the fineness of the night. He had

actually arrived at twelve o’clock, and appeared to be overwhelmed by the unexpected

tragedy. He had always been on good terms with his master. Several of the dead man’s

possessions–notably a small case of razors–had been found in the valet’s

boxes, but he explained that they had been presents from the deceased, and the housekeeper

was able to corroborate the story. Mitton had been in Lucas’s employment for three

years. It was noticeable that Lucas did not take Mitton on the Continent with him.

Sometimes he visited Paris for three months on end, but Mitton was left in charge of the

Godolphin Street house. As to the housekeeper, she had heard nothing on the night of the

crime. If her master had a visitor he had himself admitted him.

So for three mornings the mystery remained, so far as I could

follow it in the papers. If Holmes knew more, he kept his own counsel, but, as he told me

that Inspector Lestrade had taken him into his confidence in the case, I knew that he was

in close touch with every development. Upon the fourth day there appeared a long telegram

from Paris which seemed to solve the whole question. So for three mornings the mystery remained, so far as I could

follow it in the papers. If Holmes knew more, he kept his own counsel, but, as he told me

that Inspector Lestrade had taken him into his confidence in the case, I knew that he was

in close touch with every development. Upon the fourth day there appeared a long telegram

from Paris which seemed to solve the whole question.

A discovery has just been made by the Parisian police [said

the Daily Telegraph] which raises the veil which hung round the tragic fate of

Mr. Eduardo Lucas, who met his death by violence last Monday night at Godolphin Street,

Westminster. Our readers will remember that the deceased gentleman was found stabbed in

his room, and that some suspicion attached to his valet, but that the case broke down on

an alibi. Yesterday a lady, who has been known as Mme. Henri Fournaye, occupying

a small villa in the Rue Austerlitz, was reported to the authorities by her servants as

being insane. An examination showed she had indeed developed mania of a dangerous and

permanent form. On inquiry, the police have discovered that Mme. Henri Fournaye only

returned from a journey to London on Tuesday last, and there is evidence to connect her

with the crime at Westminster. [659] A

comparison of photographs has proved conclusively that M. Henri Fournaye and Eduardo Lucas

were really one and the same person, and that the deceased had for some reason lived a

double life in London and Paris. Mme. Fournaye, who is of Creole origin, is of an

extremely excitable nature, and has suffered in the past from attacks of jealousy which

have amounted to frenzy. It is conjectured that it was in one of these that she committed

the terrible crime which has caused such a sensation in London. Her movements upon the

Monday night have not yet been traced, but it is undoubted that a woman answering to her

description attracted much attention at Charing Cross Station on Tuesday morning by the

wildness of her appearance and the violence of her gestures. It is probable, therefore,

that the crime was either committed when insane, or that its immediate effect was to drive

the unhappy woman out of her mind. At present she is unable to give any coherent account

of the past, and the doctors hold out no hopes of the reestablishment of her reason. There

is evidence that a woman, who might have been Mme. Fournaye, was seen for some hours upon

Monday night watching the house in Godolphin Street. A discovery has just been made by the Parisian police [said

the Daily Telegraph] which raises the veil which hung round the tragic fate of

Mr. Eduardo Lucas, who met his death by violence last Monday night at Godolphin Street,

Westminster. Our readers will remember that the deceased gentleman was found stabbed in

his room, and that some suspicion attached to his valet, but that the case broke down on

an alibi. Yesterday a lady, who has been known as Mme. Henri Fournaye, occupying

a small villa in the Rue Austerlitz, was reported to the authorities by her servants as

being insane. An examination showed she had indeed developed mania of a dangerous and

permanent form. On inquiry, the police have discovered that Mme. Henri Fournaye only

returned from a journey to London on Tuesday last, and there is evidence to connect her

with the crime at Westminster. [659] A

comparison of photographs has proved conclusively that M. Henri Fournaye and Eduardo Lucas

were really one and the same person, and that the deceased had for some reason lived a

double life in London and Paris. Mme. Fournaye, who is of Creole origin, is of an

extremely excitable nature, and has suffered in the past from attacks of jealousy which

have amounted to frenzy. It is conjectured that it was in one of these that she committed

the terrible crime which has caused such a sensation in London. Her movements upon the

Monday night have not yet been traced, but it is undoubted that a woman answering to her

description attracted much attention at Charing Cross Station on Tuesday morning by the

wildness of her appearance and the violence of her gestures. It is probable, therefore,

that the crime was either committed when insane, or that its immediate effect was to drive

the unhappy woman out of her mind. At present she is unable to give any coherent account

of the past, and the doctors hold out no hopes of the reestablishment of her reason. There

is evidence that a woman, who might have been Mme. Fournaye, was seen for some hours upon

Monday night watching the house in Godolphin Street.

“What do you think of that, Holmes?” I had read

the account aloud to him, while he finished his breakfast. “What do you think of that, Holmes?” I had read

the account aloud to him, while he finished his breakfast.

“My dear Watson,” said he, as he rose from the table

and paced up and down the room, “you are most long-suffering, but if I have told you

nothing in the last three days, it is because there is nothing to tell. Even now this

report from Paris does not help us much.” “My dear Watson,” said he, as he rose from the table

and paced up and down the room, “you are most long-suffering, but if I have told you

nothing in the last three days, it is because there is nothing to tell. Even now this

report from Paris does not help us much.”

“Surely it is final as regards the man’s

death.” “Surely it is final as regards the man’s

death.”

“The man’s death is a mere incident–a trivial

episode–in comparison with our real task, which is to trace this document and save a

European catastrophe. Only one important thing has happened in the last three days, and

that is that nothing has happened. I get reports almost hourly from the government, and it

is certain that nowhere in Europe is there any sign of trouble. Now, if this letter were

loose–no, it can’t be loose–but if it isn’t loose, where can

it be? Who has it? Why is it held back? That’s the question that beats in my brain

like a hammer. Was it, indeed, a coincidence that Lucas should meet his death on the night

when the letter disappeared? Did the letter ever reach him? If so, why is it not among his

papers? Did this mad wife of his carry it off with her? If so, is it in her house in

Paris? How could I search for it without the French police having their suspicions

aroused? It is a case, my dear Watson, where the law is as dangerous to us as the

criminals are. Every man’s hand is against us, and yet the interests at stake are

colossal. Should I bring it to a successful conclusion, it will certainly represent the

crowning glory of my career. Ah, here is my latest from the front!” He glanced

hurriedly at the note which had been handed in. “Halloa! Lestrade seems to have

observed something of interest. Put on your hat, Watson, and we will stroll down together

to Westminster.” “The man’s death is a mere incident–a trivial

episode–in comparison with our real task, which is to trace this document and save a

European catastrophe. Only one important thing has happened in the last three days, and

that is that nothing has happened. I get reports almost hourly from the government, and it

is certain that nowhere in Europe is there any sign of trouble. Now, if this letter were

loose–no, it can’t be loose–but if it isn’t loose, where can

it be? Who has it? Why is it held back? That’s the question that beats in my brain

like a hammer. Was it, indeed, a coincidence that Lucas should meet his death on the night

when the letter disappeared? Did the letter ever reach him? If so, why is it not among his

papers? Did this mad wife of his carry it off with her? If so, is it in her house in

Paris? How could I search for it without the French police having their suspicions

aroused? It is a case, my dear Watson, where the law is as dangerous to us as the

criminals are. Every man’s hand is against us, and yet the interests at stake are

colossal. Should I bring it to a successful conclusion, it will certainly represent the

crowning glory of my career. Ah, here is my latest from the front!” He glanced

hurriedly at the note which had been handed in. “Halloa! Lestrade seems to have

observed something of interest. Put on your hat, Watson, and we will stroll down together

to Westminster.”

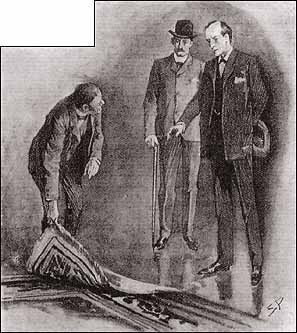

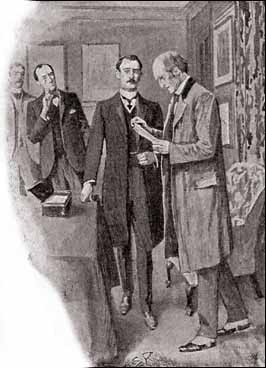

It was my first visit to the scene of the crime–a high,

dingy, narrow-chested house, prim, formal, and solid, like the century which gave it

birth. Lestrade’s bulldog features gazed out at us from the front window, and he

greeted us warmly when a big constable had opened the door and let us in. The room into

which we were shown was that in which the crime had been committed, but no trace of it now

remained save an ugly, irregular stain upon the carpet. This carpet was a [660] small square drugget in the

centre of the room, surrounded by a broad expanse of beautiful, old-fashioned

wood-flooring in square blocks, highly polished. Over the fireplace was a magnificent

trophy of weapons, one of which had been used on that tragic night. In the window was a

sumptuous writing-desk, and every detail of the apartment, the pictures, the rugs, and the

hangings, all pointed to a taste which was luxurious to the verge of effeminacy. It was my first visit to the scene of the crime–a high,

dingy, narrow-chested house, prim, formal, and solid, like the century which gave it

birth. Lestrade’s bulldog features gazed out at us from the front window, and he

greeted us warmly when a big constable had opened the door and let us in. The room into

which we were shown was that in which the crime had been committed, but no trace of it now

remained save an ugly, irregular stain upon the carpet. This carpet was a [660] small square drugget in the

centre of the room, surrounded by a broad expanse of beautiful, old-fashioned

wood-flooring in square blocks, highly polished. Over the fireplace was a magnificent

trophy of weapons, one of which had been used on that tragic night. In the window was a

sumptuous writing-desk, and every detail of the apartment, the pictures, the rugs, and the

hangings, all pointed to a taste which was luxurious to the verge of effeminacy.

“Seen the Paris news?” asked Lestrade. “Seen the Paris news?” asked Lestrade.

Holmes nodded. Holmes nodded.

“Our French friends seem to have touched the spot this

time. No doubt it’s just as they say. She knocked at the door–surprise visit, I

guess, for he kept his life in water-tight compartments–he let her in, couldn’t

keep her in the street. She told him how she had traced him, reproached him. One thing led

to another, and then with that dagger so handy the end soon came. It wasn’t all done

in an instant, though, for these chairs were all swept over yonder, and he had one in his

hand as if he had tried to hold her off with it. We’ve got it all clear as if we had

seen it.” “Our French friends seem to have touched the spot this

time. No doubt it’s just as they say. She knocked at the door–surprise visit, I

guess, for he kept his life in water-tight compartments–he let her in, couldn’t

keep her in the street. She told him how she had traced him, reproached him. One thing led

to another, and then with that dagger so handy the end soon came. It wasn’t all done

in an instant, though, for these chairs were all swept over yonder, and he had one in his

hand as if he had tried to hold her off with it. We’ve got it all clear as if we had

seen it.”

Holmes raised his eyebrows. Holmes raised his eyebrows.

“And yet you have sent for me?” “And yet you have sent for me?”

“Ah, yes, that’s another matter–a mere trifle,

but the sort of thing you take an interest in–queer, you know, and what you might

call freakish. It has nothing to do with the main fact–can’t have, on the face

of it.” “Ah, yes, that’s another matter–a mere trifle,

but the sort of thing you take an interest in–queer, you know, and what you might

call freakish. It has nothing to do with the main fact–can’t have, on the face

of it.”

“What is it, then?” “What is it, then?”

“Well, you know, after a crime of this sort we are very

careful to keep things in their position. Nothing has been moved. Officer in charge here

day and night. This morning, as the man was buried and the investigation over–so far

as this room is concerned–we thought we could tidy up a bit. This carpet. You see, it

is not fastened down, only just laid there. We had occasion to raise it. We found–

–” “Well, you know, after a crime of this sort we are very

careful to keep things in their position. Nothing has been moved. Officer in charge here

day and night. This morning, as the man was buried and the investigation over–so far

as this room is concerned–we thought we could tidy up a bit. This carpet. You see, it

is not fastened down, only just laid there. We had occasion to raise it. We found–

–”

“Yes? You found– –” “Yes? You found– –”

Holmes’s face grew tense with anxiety. Holmes’s face grew tense with anxiety.

“Well, I’m sure you would never guess in a hundred

years what we did find. You see that stain on the carpet? Well, a great deal must have

soaked through, must it not?” “Well, I’m sure you would never guess in a hundred

years what we did find. You see that stain on the carpet? Well, a great deal must have

soaked through, must it not?”

“Undoubtedly it must.” “Undoubtedly it must.”

“Well, you will be surprised to hear that there is no

stain on the white woodwork to correspond.” “Well, you will be surprised to hear that there is no

stain on the white woodwork to correspond.”

“No stain! But there must– –” “No stain! But there must– –”

“Yes, so you would say. But the fact remains that there

isn’t.” “Yes, so you would say. But the fact remains that there

isn’t.”

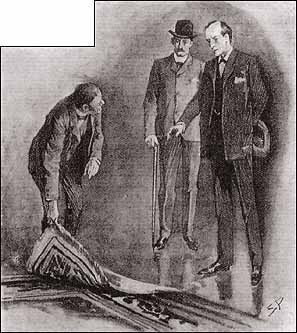

He took the corner of the carpet in his hand and, turning

it over, he showed that it was indeed as he said. He took the corner of the carpet in his hand and, turning

it over, he showed that it was indeed as he said.

“But the under side is as stained as the upper. It must

have left a mark.” “But the under side is as stained as the upper. It must

have left a mark.”

Lestrade chuckled with delight at having puzzled the famous

expert. Lestrade chuckled with delight at having puzzled the famous

expert.

“Now, I’ll show you the explanation. There is

a second stain, but it does not correspond with the other. See for yourself.” As he

spoke he turned over another portion of the carpet, and there, sure enough, was a great

crimson spill upon the square white facing of the old-fashioned floor. “What do you

make of that, Mr. Holmes?” “Now, I’ll show you the explanation. There is

a second stain, but it does not correspond with the other. See for yourself.” As he

spoke he turned over another portion of the carpet, and there, sure enough, was a great

crimson spill upon the square white facing of the old-fashioned floor. “What do you

make of that, Mr. Holmes?”

“Why, it is simple enough. The two stains did correspond,

but the carpet has been turned round. As it was square and unfastened it was easily

done.” “Why, it is simple enough. The two stains did correspond,

but the carpet has been turned round. As it was square and unfastened it was easily

done.”

“The official police don’t need you, Mr. Holmes, to

tell them that the carpet must have been turned round. That’s clear enough, for the

stains lie above each [661] other–if

you lay it over this way. But what I want to know is, who shifted the carpet, and

why?” “The official police don’t need you, Mr. Holmes, to

tell them that the carpet must have been turned round. That’s clear enough, for the

stains lie above each [661] other–if

you lay it over this way. But what I want to know is, who shifted the carpet, and

why?”

I could see from Holmes’s rigid face that he was

vibrating with inward excitement. I could see from Holmes’s rigid face that he was

vibrating with inward excitement.

“Look here, Lestrade,” said he, “has that

constable in the passage been in charge of the place all the time?” “Look here, Lestrade,” said he, “has that

constable in the passage been in charge of the place all the time?”

“Yes, he has.” “Yes, he has.”

“Well, take my advice. Examine him carefully. Don’t

do it before us. We’ll wait here. You take him into the back room. You’ll be

more likely to get a confession out of him alone. Ask him how he dared to admit people and

leave them alone in this room. Don’t ask him if he has done it. Take it for granted.

Tell him you know someone has been here. Press him. Tell him that a full confession is his

only chance of forgiveness. Do exactly what I tell you!” “Well, take my advice. Examine him carefully. Don’t

do it before us. We’ll wait here. You take him into the back room. You’ll be

more likely to get a confession out of him alone. Ask him how he dared to admit people and

leave them alone in this room. Don’t ask him if he has done it. Take it for granted.

Tell him you know someone has been here. Press him. Tell him that a full confession is his

only chance of forgiveness. Do exactly what I tell you!”

“By George, if he knows I’ll have it out of

him!” cried Lestrade. He darted into the hall, and a few moments later his bullying

voice sounded from the back room. “By George, if he knows I’ll have it out of

him!” cried Lestrade. He darted into the hall, and a few moments later his bullying

voice sounded from the back room.

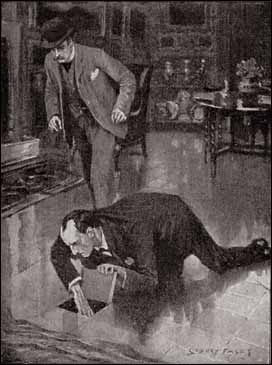

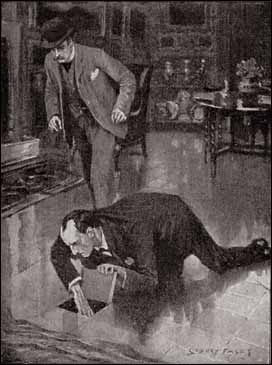

“Now, Watson, now!” cried Holmes with frenzied

eagerness. All the demoniacal force of the man masked behind that listless manner burst

out in a paroxysm of energy. He tore the drugget from the floor, and in an instant was

down on his hands and knees clawing at each of the squares of wood beneath it. One turned

sideways as he dug his nails into the edge of it. It hinged back like the lid of a box. A

small black cavity opened beneath it. Holmes plunged his eager hand into it and drew it

out with a bitter snarl of anger and disappointment. It was empty. “Now, Watson, now!” cried Holmes with frenzied

eagerness. All the demoniacal force of the man masked behind that listless manner burst

out in a paroxysm of energy. He tore the drugget from the floor, and in an instant was

down on his hands and knees clawing at each of the squares of wood beneath it. One turned

sideways as he dug his nails into the edge of it. It hinged back like the lid of a box. A

small black cavity opened beneath it. Holmes plunged his eager hand into it and drew it

out with a bitter snarl of anger and disappointment. It was empty.

“Quick, Watson, quick! Get it back again!” The

wooden lid was replaced, and the drugget had only just been drawn straight when

Lestrade’s voice was heard in the passage. He found Holmes leaning languidly against

the mantelpiece, resigned and patient, endeavouring to conceal his irrepressible yawns. “Quick, Watson, quick! Get it back again!” The

wooden lid was replaced, and the drugget had only just been drawn straight when

Lestrade’s voice was heard in the passage. He found Holmes leaning languidly against

the mantelpiece, resigned and patient, endeavouring to conceal his irrepressible yawns.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, Mr. Holmes. I can see that

you are bored to death with the whole affair. Well, he has confessed, all right. Come in

here, MacPherson. Let these gentlemen hear of your most inexcusable conduct.” “Sorry to keep you waiting, Mr. Holmes. I can see that

you are bored to death with the whole affair. Well, he has confessed, all right. Come in

here, MacPherson. Let these gentlemen hear of your most inexcusable conduct.”

The big constable, very hot and penitent, sidled into the

room. The big constable, very hot and penitent, sidled into the

room.

“I meant no harm, sir, I’m sure. The young woman

came to the door last evening–mistook the house, she did. And then we got talking.

It’s lonesome, when you’re on duty here all day.” “I meant no harm, sir, I’m sure. The young woman

came to the door last evening–mistook the house, she did. And then we got talking.

It’s lonesome, when you’re on duty here all day.”

“Well, what happened then?” “Well, what happened then?”

“She wanted to see where the crime was done–had read

about it in the papers, she said. She was a very respectable, well-spoken young woman,

sir, and I saw no harm in letting her have a peep. When she saw that mark on the carpet,

down she dropped on the floor, and lay as if she were dead. I ran to the back and got some

water, but I could not bring her to. Then I went round the corner to the Ivy Plant for

some brandy, and by the time I had brought it back the young woman had recovered and was

off–ashamed of herself, I daresay, and dared not face me.” “She wanted to see where the crime was done–had read

about it in the papers, she said. She was a very respectable, well-spoken young woman,

sir, and I saw no harm in letting her have a peep. When she saw that mark on the carpet,

down she dropped on the floor, and lay as if she were dead. I ran to the back and got some

water, but I could not bring her to. Then I went round the corner to the Ivy Plant for

some brandy, and by the time I had brought it back the young woman had recovered and was

off–ashamed of herself, I daresay, and dared not face me.”

“How about moving that drugget?” “How about moving that drugget?”

“Well, sir, it was a bit rumpled, certainly, when I came

back. You see, she fell on it and it lies on a polished floor with nothing to keep it in

place. I straightened it out afterwards.” “Well, sir, it was a bit rumpled, certainly, when I came

back. You see, she fell on it and it lies on a polished floor with nothing to keep it in

place. I straightened it out afterwards.”

“It’s a lesson to you that you can’t deceive

me, Constable MacPherson,” said Lestrade, with dignity. “No doubt you thought

that your breach of duty could never be discovered, and yet a mere glance at that drugget

was enough to convince me [662] that

someone had been admitted to the room. It’s lucky for you, my man, that nothing is

missing, or you would find yourself in Queer Street. I’m sorry to have called you

down over such a petty business, Mr. Holmes, but I thought the point of the second stain

not corresponding with the first would interest you.” “It’s a lesson to you that you can’t deceive

me, Constable MacPherson,” said Lestrade, with dignity. “No doubt you thought

that your breach of duty could never be discovered, and yet a mere glance at that drugget

was enough to convince me [662] that

someone had been admitted to the room. It’s lucky for you, my man, that nothing is

missing, or you would find yourself in Queer Street. I’m sorry to have called you

down over such a petty business, Mr. Holmes, but I thought the point of the second stain

not corresponding with the first would interest you.”

“Certainly, it was most interesting. Has this woman only

been here once, constable?” “Certainly, it was most interesting. Has this woman only

been here once, constable?”

“Yes, sir, only once.” “Yes, sir, only once.”

“Who was she?” “Who was she?”

“Don’t know the name, sir. Was answering an

advertisement about typewriting and came to the wrong number–very pleasant, genteel

young woman, sir.” “Don’t know the name, sir. Was answering an

advertisement about typewriting and came to the wrong number–very pleasant, genteel

young woman, sir.”

“Tall? Handsome?” “Tall? Handsome?”

“Yes, sir, she was a well-grown young woman. I suppose

you might say she was handsome. Perhaps some would say she was very handsome. ‘Oh,

officer, do let me have a peep!’ says she. She had pretty, coaxing ways, as you might

say, and I thought there was no harm in letting her just put her head through the

door.” “Yes, sir, she was a well-grown young woman. I suppose

you might say she was handsome. Perhaps some would say she was very handsome. ‘Oh,

officer, do let me have a peep!’ says she. She had pretty, coaxing ways, as you might

say, and I thought there was no harm in letting her just put her head through the

door.”

“How was she dressed?” “How was she dressed?”

“Quiet, sir–a long mantle down to her feet.” “Quiet, sir–a long mantle down to her feet.”

“What time was it?” “What time was it?”

“It was just growing dusk at the time. They were lighting

the lamps as I came back with the brandy.” “It was just growing dusk at the time. They were lighting

the lamps as I came back with the brandy.”

“Very good,” said Holmes. “Come, Watson, I

think that we have more important work elsewhere.” “Very good,” said Holmes. “Come, Watson, I

think that we have more important work elsewhere.”

As we left the house Lestrade remained in the front room,

while the repentant constable opened the door to let us out. Holmes turned on the step and

held up something in his hand. The constable stared intently. As we left the house Lestrade remained in the front room,

while the repentant constable opened the door to let us out. Holmes turned on the step and

held up something in his hand. The constable stared intently.

“Good Lord, sir!” he cried, with amazement on his

face. Holmes put his finger on his lips, replaced his hand in his breast pocket, and burst

out laughing as we turned down the street. “Excellent!” said he. “Come,

friend Watson, the curtain rings up for the last act. You will be relieved to hear that

there will be no war, that the Right Honourable Trelawney Hope will suffer no setback in

his brilliant career, that the indiscreet Sovereign will receive no punishment for his

indiscretion, that the Prime Minister will have no European complication to deal with, and

that with a little tact and management upon our part nobody will be a penny the worse for

what might have been a very ugly incident.” “Good Lord, sir!” he cried, with amazement on his

face. Holmes put his finger on his lips, replaced his hand in his breast pocket, and burst

out laughing as we turned down the street. “Excellent!” said he. “Come,

friend Watson, the curtain rings up for the last act. You will be relieved to hear that

there will be no war, that the Right Honourable Trelawney Hope will suffer no setback in

his brilliant career, that the indiscreet Sovereign will receive no punishment for his

indiscretion, that the Prime Minister will have no European complication to deal with, and

that with a little tact and management upon our part nobody will be a penny the worse for

what might have been a very ugly incident.”

My mind filled with admiration for this extraordinary man. My mind filled with admiration for this extraordinary man.

“You have solved it!” I cried. “You have solved it!” I cried.

“Hardly that, Watson. There are some points which are as

dark as ever. But we have so much that it will be our own fault if we cannot get the rest.

We will go straight to Whitehall Terrace and bring the matter to a head.” “Hardly that, Watson. There are some points which are as

dark as ever. But we have so much that it will be our own fault if we cannot get the rest.

We will go straight to Whitehall Terrace and bring the matter to a head.”

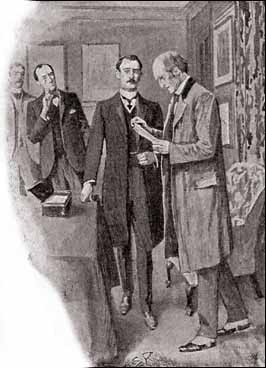

When we arrived at the residence of the European Secretary it

was for Lady Hilda Trelawney Hope that Sherlock Holmes inquired. We were shown into the

morning-room. When we arrived at the residence of the European Secretary it

was for Lady Hilda Trelawney Hope that Sherlock Holmes inquired. We were shown into the

morning-room.

“Mr. Holmes!” said the lady, and her face was pink

with her indignation. “This is surely most unfair and ungenerous upon your part. I

desired, as I have explained, to keep my visit to you a secret, lest my husband should

think that I was intruding into his affairs. And yet you compromise me by coming here and

so showing that there are business relations between us.” “Mr. Holmes!” said the lady, and her face was pink

with her indignation. “This is surely most unfair and ungenerous upon your part. I

desired, as I have explained, to keep my visit to you a secret, lest my husband should

think that I was intruding into his affairs. And yet you compromise me by coming here and

so showing that there are business relations between us.”

“Unfortunately, madam, I had no possible alternative. I

have been commissioned [663] to

recover this immensely important paper. I must therefore ask you, madam, to be kind enough

to place it in my hands.” “Unfortunately, madam, I had no possible alternative. I

have been commissioned [663] to

recover this immensely important paper. I must therefore ask you, madam, to be kind enough

to place it in my hands.”

The lady sprang to her feet, with the colour all dashed in an

instant from her beautiful face. Her eyes glazed–she tottered–I thought that she

would faint. Then with a grand effort she rallied from the shock, and a supreme

astonishment and indignation chased every other expression from her features. The lady sprang to her feet, with the colour all dashed in an

instant from her beautiful face. Her eyes glazed–she tottered–I thought that she

would faint. Then with a grand effort she rallied from the shock, and a supreme

astonishment and indignation chased every other expression from her features.

“You–you insult me, Mr. Holmes.” “You–you insult me, Mr. Holmes.”

“Come, come, madam, it is useless. Give up the

letter.” “Come, come, madam, it is useless. Give up the

letter.”

She darted to the bell. She darted to the bell.

“The butler shall show you out.” “The butler shall show you out.”

“Do not ring, Lady Hilda. If you do, then all my earnest

efforts to avoid a scandal will be frustrated. Give up the letter and all will be set

right. If you will work with me I can arrange everything. If you work against me I must

expose you.” “Do not ring, Lady Hilda. If you do, then all my earnest

efforts to avoid a scandal will be frustrated. Give up the letter and all will be set

right. If you will work with me I can arrange everything. If you work against me I must

expose you.”

She stood grandly defiant, a queenly figure, her eyes fixed

upon his as if she would read his very soul. Her hand was on the bell, but she had

forborne to ring it. She stood grandly defiant, a queenly figure, her eyes fixed

upon his as if she would read his very soul. Her hand was on the bell, but she had

forborne to ring it.

“You are trying to frighten me. It is not a very manly

thing, Mr. Holmes, to come here and browbeat a woman. You say that you know something.

What is it that you know?” “You are trying to frighten me. It is not a very manly

thing, Mr. Holmes, to come here and browbeat a woman. You say that you know something.

What is it that you know?”

“Pray sit down, madam. You will hurt yourself there if

you fall. I will not speak until you sit down. Thank you.” “Pray sit down, madam. You will hurt yourself there if

you fall. I will not speak until you sit down. Thank you.”

“I give you five minutes, Mr. Holmes.” “I give you five minutes, Mr. Holmes.”

“One is enough, Lady Hilda. I know of your visit to

Eduardo Lucas, of your giving him this document, of your ingenious return to the room last

night, and of the manner in which you took the letter from the hiding-place under the

carpet.” “One is enough, Lady Hilda. I know of your visit to

Eduardo Lucas, of your giving him this document, of your ingenious return to the room last

night, and of the manner in which you took the letter from the hiding-place under the

carpet.”

She stared at him with an ashen face and gulped twice before

she could speak. She stared at him with an ashen face and gulped twice before

she could speak.

“You are mad, Mr. Holmes–you are mad!” she

cried, at last. “You are mad, Mr. Holmes–you are mad!” she

cried, at last.

He drew a small piece of cardboard from his pocket. It was the

face of a woman cut out of a portrait. He drew a small piece of cardboard from his pocket. It was the

face of a woman cut out of a portrait.

“I have carried this because I thought it might be

useful,” said he. “The policeman has recognized it.” “I have carried this because I thought it might be

useful,” said he. “The policeman has recognized it.”

She gave a gasp, and her head dropped back in the chair. She gave a gasp, and her head dropped back in the chair.

“Come, Lady Hilda. You have the letter. The matter may

still be adjusted. I have no desire to bring trouble to you. My duty ends when I have

returned the lost letter to your husband. Take my advice and be frank with me. It is your

only chance.” “Come, Lady Hilda. You have the letter. The matter may

still be adjusted. I have no desire to bring trouble to you. My duty ends when I have

returned the lost letter to your husband. Take my advice and be frank with me. It is your

only chance.”

Her courage was admirable. Even now she would not own defeat. Her courage was admirable. Even now she would not own defeat.

“I tell you again, Mr. Holmes, that you are under some

absurd illusion.” “I tell you again, Mr. Holmes, that you are under some

absurd illusion.”

Holmes rose from his chair. Holmes rose from his chair.

“I am sorry for you, Lady Hilda. I have done my best for

you. I can see that it is all in vain.” “I am sorry for you, Lady Hilda. I have done my best for

you. I can see that it is all in vain.”

He rang the bell. The butler entered. He rang the bell. The butler entered.

“Is Mr. Trelawney Hope at home?” “Is Mr. Trelawney Hope at home?”

“He will be home, sir, at a quarter to one.” “He will be home, sir, at a quarter to one.”

Holmes glanced at his watch. Holmes glanced at his watch.

“Still a quarter of an hour,” said he. “Very

good, I shall wait.” “Still a quarter of an hour,” said he. “Very

good, I shall wait.”

The butler had hardly closed the door behind him when Lady

Hilda was down on her knees at Holmes’s feet, her hands outstretched, her beautiful

face upturned and wet with her tears. The butler had hardly closed the door behind him when Lady

Hilda was down on her knees at Holmes’s feet, her hands outstretched, her beautiful

face upturned and wet with her tears.

“Oh, spare me, Mr. Holmes! Spare me!” she pleaded,

in a frenzy of [664] supplication.

“For heaven’s sake, don’t tell him! I love him so! I would not bring one

shadow on his life, and this I know would break his noble heart.” “Oh, spare me, Mr. Holmes! Spare me!” she pleaded,

in a frenzy of [664] supplication.

“For heaven’s sake, don’t tell him! I love him so! I would not bring one

shadow on his life, and this I know would break his noble heart.”

Holmes raised the lady. “I am thankful, madam, that you

have come to your senses even at this last moment! There is not an instant to lose. Where

is the letter?” Holmes raised the lady. “I am thankful, madam, that you

have come to your senses even at this last moment! There is not an instant to lose. Where

is the letter?”

She darted across to a writing-desk, unlocked it, and drew out

a long blue envelope. She darted across to a writing-desk, unlocked it, and drew out

a long blue envelope.

“Here it is, Mr. Holmes. Would to heaven I had never seen

it!” “Here it is, Mr. Holmes. Would to heaven I had never seen

it!”

“How can we return it?” Holmes muttered.

“Quick, quick, we must think of some way! Where is the despatch-box?” “How can we return it?” Holmes muttered.

“Quick, quick, we must think of some way! Where is the despatch-box?”

“Still in his bedroom.” “Still in his bedroom.”

“What a stroke of luck! Quick, madam, bring it

here!” “What a stroke of luck! Quick, madam, bring it

here!”

A moment later she had appeared with a red flat box in her

hand. A moment later she had appeared with a red flat box in her

hand.

“How did you open it before? You have a duplicate key?