|

|

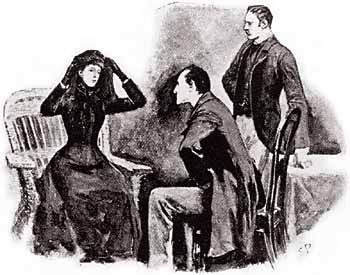

“It is fear, Mr. Holmes. It is terror.” She raised

her veil as she spoke, and we could see that she was indeed in a pitiable state of

agitation, her face all drawn and gray, with restless, frightened eyes, like those of some

hunted animal. Her features and figure were those of a woman of thirty, but her hair was

shot with premature gray, and her expression was weary and haggard. Sherlock Holmes ran

her over with one of his quick, all-comprehensive glances. “It is fear, Mr. Holmes. It is terror.” She raised

her veil as she spoke, and we could see that she was indeed in a pitiable state of

agitation, her face all drawn and gray, with restless, frightened eyes, like those of some

hunted animal. Her features and figure were those of a woman of thirty, but her hair was

shot with premature gray, and her expression was weary and haggard. Sherlock Holmes ran

her over with one of his quick, all-comprehensive glances.

“You must not fear,” said he soothingly, bending

forward and patting her forearm. “We shall soon set matters right, I have no doubt.

You have come in by train this morning, I see.” “You must not fear,” said he soothingly, bending

forward and patting her forearm. “We shall soon set matters right, I have no doubt.

You have come in by train this morning, I see.”

“You know me, then?” “You know me, then?”

“No, but I observe the second half of a return ticket in

the palm of your left [259] glove.

You must have started early, and yet you had a good drive in a dog-cart, along heavy

roads, before you reached the station.” “No, but I observe the second half of a return ticket in

the palm of your left [259] glove.

You must have started early, and yet you had a good drive in a dog-cart, along heavy

roads, before you reached the station.”

The lady gave a violent start and stared in bewilderment at my

companion. The lady gave a violent start and stared in bewilderment at my

companion.

“There is no mystery, my dear madam,” said he,

smiling. “The left arm of your jacket is spattered with mud in no less than seven

places. The marks are perfectly fresh. There is no vehicle save a dog-cart which throws up

mud in that way, and then only when you sit on the left-hand side of the driver.” “There is no mystery, my dear madam,” said he,

smiling. “The left arm of your jacket is spattered with mud in no less than seven

places. The marks are perfectly fresh. There is no vehicle save a dog-cart which throws up

mud in that way, and then only when you sit on the left-hand side of the driver.”

“Whatever your reasons may be, you are perfectly

correct,” said she. “I started from home before six, reached Leatherhead at

twenty past, and came in by the first train to Waterloo. Sir, I can stand this strain no

longer; I shall go mad if it continues. I have no one to turn to–none, save only one,

who cares for me, and he, poor fellow, can be of little aid. I have heard of you, Mr.

Holmes; I have heard of you from Mrs. Farintosh, whom you helped in the hour of her sore

need. It was from her that I had your address. Oh, sir, do you not think that you could

help me, too, and at least throw a little light through the dense darkness which surrounds

me? At present it is out of my power to reward you for your services, but in a month or

six weeks I shall be married, with the control of my own income, and then at least you

shall not find me ungrateful.” “Whatever your reasons may be, you are perfectly

correct,” said she. “I started from home before six, reached Leatherhead at

twenty past, and came in by the first train to Waterloo. Sir, I can stand this strain no

longer; I shall go mad if it continues. I have no one to turn to–none, save only one,

who cares for me, and he, poor fellow, can be of little aid. I have heard of you, Mr.

Holmes; I have heard of you from Mrs. Farintosh, whom you helped in the hour of her sore

need. It was from her that I had your address. Oh, sir, do you not think that you could

help me, too, and at least throw a little light through the dense darkness which surrounds

me? At present it is out of my power to reward you for your services, but in a month or

six weeks I shall be married, with the control of my own income, and then at least you

shall not find me ungrateful.”

Holmes turned to his desk and, unlocking it, drew out a small

case-book, which he consulted. Holmes turned to his desk and, unlocking it, drew out a small

case-book, which he consulted.

“Farintosh,” said he. “Ah yes, I recall the

case; it was concerned with an opal tiara. I think it was before your time, Watson. I can

only say, madam, that I shall be happy to devote the same care to your case as I did to

that of your friend. As to reward, my profession is its own reward; but you are at liberty

to defray whatever expenses I may be put to, at the time which suits you best. And now I

beg that you will lay before us everything that may help us in forming an opinion upon the

matter.” “Farintosh,” said he. “Ah yes, I recall the

case; it was concerned with an opal tiara. I think it was before your time, Watson. I can

only say, madam, that I shall be happy to devote the same care to your case as I did to

that of your friend. As to reward, my profession is its own reward; but you are at liberty

to defray whatever expenses I may be put to, at the time which suits you best. And now I

beg that you will lay before us everything that may help us in forming an opinion upon the

matter.”

“Alas!” replied our visitor, “the very horror

of my situation lies in the fact that my fears are so vague, and my suspicions depend so

entirely upon small points, which might seem trivial to another, that even he to whom of

all others I have a right to look for help and advice looks upon all that I tell him about

it as the fancies of a nervous woman. He does not say so, but I can read it from his

soothing answers and averted eyes. But I have heard, Mr. Holmes, that you can see deeply

into the manifold wickedness of the human heart. You may advise me how to walk amid the

dangers which encompass me.” “Alas!” replied our visitor, “the very horror

of my situation lies in the fact that my fears are so vague, and my suspicions depend so

entirely upon small points, which might seem trivial to another, that even he to whom of

all others I have a right to look for help and advice looks upon all that I tell him about

it as the fancies of a nervous woman. He does not say so, but I can read it from his

soothing answers and averted eyes. But I have heard, Mr. Holmes, that you can see deeply

into the manifold wickedness of the human heart. You may advise me how to walk amid the

dangers which encompass me.”

“I am all attention, madam.” “I am all attention, madam.”

“My name is Helen Stoner, and I am living with my

stepfather, who is the last survivor of one of the oldest Saxon families in England, the

Roylotts of Stoke Moran, on the western border of Surrey.” “My name is Helen Stoner, and I am living with my

stepfather, who is the last survivor of one of the oldest Saxon families in England, the

Roylotts of Stoke Moran, on the western border of Surrey.”

Holmes nodded his head. “The name is familiar to

me,” said he. Holmes nodded his head. “The name is familiar to

me,” said he.

“The family was at one time among the richest in England,

and the estates extended over the borders into Berkshire in the north, and Hampshire in

the west. In the last century, however, four successive heirs were of a dissolute and

wasteful disposition, and the family ruin was eventually completed by a gambler in the

days of the Regency. Nothing was left save a few acres of ground, and the

two-hundred-year-old house, which is itself crushed under a heavy mortgage. The last

squire dragged out his existence there, living the horrible life of an aristocratic

pauper; but his only son, my stepfather, seeing that he must adapt himself to the new

conditions, obtained an advance from a relative, which enabled him to take a [260] medical degree and went out to

Calcutta, where, by his professional skill and his force of character, he established a

large practice. In a fit of anger, however, caused by some robberies which had been

perpetrated in the house, he beat his native butler to death and narrowly escaped a

capital sentence. As it was, he suffered a long term of imprisonment and afterwards

returned to England a morose and disappointed man. “The family was at one time among the richest in England,

and the estates extended over the borders into Berkshire in the north, and Hampshire in

the west. In the last century, however, four successive heirs were of a dissolute and

wasteful disposition, and the family ruin was eventually completed by a gambler in the

days of the Regency. Nothing was left save a few acres of ground, and the

two-hundred-year-old house, which is itself crushed under a heavy mortgage. The last

squire dragged out his existence there, living the horrible life of an aristocratic

pauper; but his only son, my stepfather, seeing that he must adapt himself to the new

conditions, obtained an advance from a relative, which enabled him to take a [260] medical degree and went out to

Calcutta, where, by his professional skill and his force of character, he established a

large practice. In a fit of anger, however, caused by some robberies which had been

perpetrated in the house, he beat his native butler to death and narrowly escaped a

capital sentence. As it was, he suffered a long term of imprisonment and afterwards

returned to England a morose and disappointed man.

“When Dr. Roylott was in India he married my mother, Mrs.

Stoner, the young widow of Major-General Stoner, of the Bengal Artillery. My sister Julia

and I were twins, and we were only two years old at the time of my mother’s

re-marriage. She had a considerable sum of money–not less than ´┐Ż1000 a year

–and this she bequeathed to Dr. Roylott entirely while we resided with him, with a

provision that a certain annual sum should be allowed to each of us in the event of our

marriage. Shortly after our return to England my mother died –she was killed eight

years ago in a railway accident near Crewe. Dr. Roylott then abandoned his attempts to

establish himself in practice in London and took us to live with him in the old ancestral

house at Stoke Moran. The money which my mother had left was enough for all our wants, and

there seemed to be no obstacle to our happiness. “When Dr. Roylott was in India he married my mother, Mrs.

Stoner, the young widow of Major-General Stoner, of the Bengal Artillery. My sister Julia

and I were twins, and we were only two years old at the time of my mother’s

re-marriage. She had a considerable sum of money–not less than ´┐Ż1000 a year

–and this she bequeathed to Dr. Roylott entirely while we resided with him, with a

provision that a certain annual sum should be allowed to each of us in the event of our

marriage. Shortly after our return to England my mother died –she was killed eight

years ago in a railway accident near Crewe. Dr. Roylott then abandoned his attempts to

establish himself in practice in London and took us to live with him in the old ancestral

house at Stoke Moran. The money which my mother had left was enough for all our wants, and

there seemed to be no obstacle to our happiness.

“But a terrible change came over our stepfather about

this time. Instead of making friends and exchanging visits with our neighbours, who had at

first been overjoyed to see a Roylott of Stoke Moran back in the old family seat, he shut

himself up in his house and seldom came out save to indulge in ferocious quarrels with

whoever might cross his path. Violence of temper approaching to mania has been hereditary

in the men of the family, and in my stepfather’s case it had, I believe, been

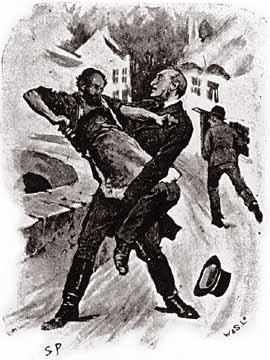

intensified by his long residence in the tropics. A series of disgraceful brawls took

place, two of which ended in the police-court, until at last he became the terror of the

village, and the folks would fly at his approach, for he is a man of immense strength, and

absolutely uncontrollable in his anger. “But a terrible change came over our stepfather about

this time. Instead of making friends and exchanging visits with our neighbours, who had at

first been overjoyed to see a Roylott of Stoke Moran back in the old family seat, he shut

himself up in his house and seldom came out save to indulge in ferocious quarrels with

whoever might cross his path. Violence of temper approaching to mania has been hereditary

in the men of the family, and in my stepfather’s case it had, I believe, been

intensified by his long residence in the tropics. A series of disgraceful brawls took

place, two of which ended in the police-court, until at last he became the terror of the

village, and the folks would fly at his approach, for he is a man of immense strength, and

absolutely uncontrollable in his anger.

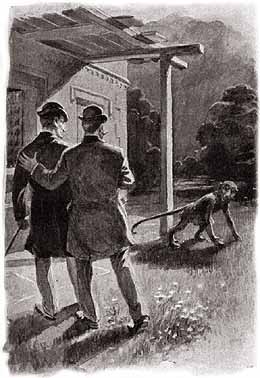

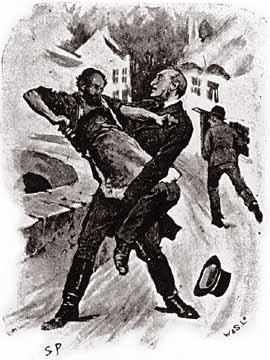

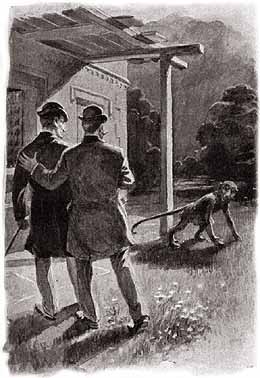

“Last week he hurled the local blacksmith over a

parapet into a stream, and it was only by paying over all the money which I could gather

together that I was able to avert another public exposure. He had no friends at all save

the wandering gypsies, and he would give these vagabonds leave to encamp upon the few

acres of bramble-covered land which represent the family estate, and would accept in

return the hospitality of their tents, wandering away with them sometimes for weeks on

end. He has a passion also for Indian animals, which are sent over to him by a

correspondent, and he has at this moment a cheetah and a baboon, which wander freely over

his grounds and are feared by the villagers almost as much as their master. “Last week he hurled the local blacksmith over a

parapet into a stream, and it was only by paying over all the money which I could gather

together that I was able to avert another public exposure. He had no friends at all save

the wandering gypsies, and he would give these vagabonds leave to encamp upon the few

acres of bramble-covered land which represent the family estate, and would accept in

return the hospitality of their tents, wandering away with them sometimes for weeks on

end. He has a passion also for Indian animals, which are sent over to him by a

correspondent, and he has at this moment a cheetah and a baboon, which wander freely over

his grounds and are feared by the villagers almost as much as their master.

“You can imagine from what I say that my poor sister

Julia and I had no great pleasure in our lives. No servant would stay with us, and for a

long time we did all the work of the house. She was but thirty at the time of her death,

and yet her hair had already begun to whiten, even as mine has.” “You can imagine from what I say that my poor sister

Julia and I had no great pleasure in our lives. No servant would stay with us, and for a

long time we did all the work of the house. She was but thirty at the time of her death,

and yet her hair had already begun to whiten, even as mine has.”

“Your sister is dead, then?” “Your sister is dead, then?”

“She died just two years ago, and it is of her death that

I wish to speak to you. You can understand that, living the life which I have described,

we were little likely to see anyone of our own age and position. We had, however, an aunt,

my mother’s maiden sister, Miss Honoria Westphail, who lives near Harrow, and we were

occasionally allowed to pay short visits at this lady’s house. Julia went there at

Christmas two years ago, and met there a half-pay major of marines, to whom she became

engaged. My stepfather learned of the engagement when my sister [261] returned and offered no objection

to the marriage; but within a fortnight of the day which had been fixed for the wedding,

the terrible event occurred which has deprived me of my only companion.” “She died just two years ago, and it is of her death that

I wish to speak to you. You can understand that, living the life which I have described,

we were little likely to see anyone of our own age and position. We had, however, an aunt,

my mother’s maiden sister, Miss Honoria Westphail, who lives near Harrow, and we were

occasionally allowed to pay short visits at this lady’s house. Julia went there at

Christmas two years ago, and met there a half-pay major of marines, to whom she became

engaged. My stepfather learned of the engagement when my sister [261] returned and offered no objection

to the marriage; but within a fortnight of the day which had been fixed for the wedding,

the terrible event occurred which has deprived me of my only companion.”

Sherlock Holmes had been leaning back in his chair with his

eyes closed and his head sunk in a cushion, but he half opened his lids now and glanced

across at his visitor. Sherlock Holmes had been leaning back in his chair with his

eyes closed and his head sunk in a cushion, but he half opened his lids now and glanced

across at his visitor.

“Pray be precise as to details,” said he. “Pray be precise as to details,” said he.

“It is easy for me to be so, for every event of that

dreadful time is seared into my memory. The manor-house is, as I have already said, very

old, and only one wing is now inhabited. The bedrooms in this wing are on the ground

floor, the sitting-rooms being in the central block of the buildings. Of these bedrooms

the first is Dr. Roylott’s, the second my sister’s, and the third my own. There

is no communication between them, but they all open out into the same corridor. Do I make

myself plain?” “It is easy for me to be so, for every event of that

dreadful time is seared into my memory. The manor-house is, as I have already said, very

old, and only one wing is now inhabited. The bedrooms in this wing are on the ground

floor, the sitting-rooms being in the central block of the buildings. Of these bedrooms

the first is Dr. Roylott’s, the second my sister’s, and the third my own. There

is no communication between them, but they all open out into the same corridor. Do I make

myself plain?”

“Perfectly so.” “Perfectly so.”

“The windows of the three rooms open out upon the lawn.

That fatal night Dr. Roylott had gone to his room early, though we knew that he had not

retired to rest, for my sister was troubled by the smell of the strong Indian cigars which

it was his custom to smoke. She left her room, therefore, and came into mine, where she

sat for some time, chatting about her approaching wedding. At eleven o’clock she rose

to leave me, but she paused at the door and looked back. “The windows of the three rooms open out upon the lawn.

That fatal night Dr. Roylott had gone to his room early, though we knew that he had not

retired to rest, for my sister was troubled by the smell of the strong Indian cigars which

it was his custom to smoke. She left her room, therefore, and came into mine, where she

sat for some time, chatting about her approaching wedding. At eleven o’clock she rose

to leave me, but she paused at the door and looked back.

“ ‘Tell me, Helen,’ said she, ‘have you

ever heard anyone whistle in the dead of the night?’ “ ‘Tell me, Helen,’ said she, ‘have you

ever heard anyone whistle in the dead of the night?’

“ ‘Never,’ said I. “ ‘Never,’ said I.

“ ‘I suppose that you could not possibly whistle,

yourself, in your sleep?’ “ ‘I suppose that you could not possibly whistle,

yourself, in your sleep?’

“ ‘Certainly not. But why?’ “ ‘Certainly not. But why?’

“ ‘Because during the last few nights I have always,

about three in the morning, heard a low, clear whistle. I am a light sleeper, and it has

awakened me. I cannot tell where it came from–perhaps from the next room, perhaps

from the lawn. I thought that I would just ask you whether you had heard it.’ “ ‘Because during the last few nights I have always,

about three in the morning, heard a low, clear whistle. I am a light sleeper, and it has

awakened me. I cannot tell where it came from–perhaps from the next room, perhaps

from the lawn. I thought that I would just ask you whether you had heard it.’

“ ‘No, I have not. It must be those wretched gypsies

in the plantation.’ “ ‘No, I have not. It must be those wretched gypsies

in the plantation.’

“ ‘Very likely. And yet if it were on the lawn, I

wonder that you did not hear it also.’ “ ‘Very likely. And yet if it were on the lawn, I

wonder that you did not hear it also.’

“ ‘Ah, but I sleep more heavily than you.’ “ ‘Ah, but I sleep more heavily than you.’

“ ‘Well, it is of no great consequence, at any

rate.’ She smiled back at me, closed my door, and a few moments later I heard her key

turn in the lock.” “ ‘Well, it is of no great consequence, at any

rate.’ She smiled back at me, closed my door, and a few moments later I heard her key

turn in the lock.”

“Indeed,” said Holmes. “Was it your custom

always to lock yourselves in at night?” “Indeed,” said Holmes. “Was it your custom

always to lock yourselves in at night?”

“Always.” “Always.”

“And why?” “And why?”

“I think that I mentioned to you that the doctor kept a

cheetah and a baboon. We had no feeling of security unless our doors were locked.” “I think that I mentioned to you that the doctor kept a

cheetah and a baboon. We had no feeling of security unless our doors were locked.”

“Quite so. Pray proceed with your statement.” “Quite so. Pray proceed with your statement.”

“I could not sleep that night. A vague feeling of

impending misfortune impressed me. My sister and I, you will recollect, were twins, and

you know how subtle are the links which bind two souls which are so closely allied. It was

a wild night. The wind was howling outside, and the rain was beating and splashing against

the windows. Suddenly, amid all the hubbub of the gale, there burst forth the wild scream

of a terrified woman. I knew that it was my sister’s voice. I sprang from my bed,

wrapped a shawl round me, and rushed into the corridor. As I [262] opened my door I seemed to hear a low whistle, such as

my sister described, and a few moments later a clanging sound, as if a mass of metal had

fallen. As I ran down the passage, my sister’s door was unlocked, and revolved slowly

upon its hinges. I stared at it horror-stricken, not knowing what was about to issue from

it. By the light of the corridor-lamp I saw my sister appear at the opening, her face

blanched with terror, her hands groping for help, her whole figure swaying to and fro like

that of a drunkard. I ran to her and threw my arms round her, but at that moment her knees

seemed to give way and she fell to the ground. She writhed as one who is in terrible pain,

and her limbs were dreadfully convulsed. At first I thought that she had not recognized

me, but as I bent over her she suddenly shrieked out in a voice which I shall never

forget, ‘Oh, my God! Helen! It was the band! The speckled band!’ There was

something else which she would fain have said, and she stabbed with her finger into the

air in the direction of the doctor’s room, but a fresh convulsion seized her and

choked her words. I rushed out, calling loudly for my stepfather, and I met him hastening

from his room in his dressing-gown. When he reached my sister’s side she was

unconscious, and though he poured brandy down her throat and sent for medical aid from the

village, all efforts were in vain, for she slowly sank and died without having recovered

her consciousness. Such was the dreadful end of my beloved sister.” “I could not sleep that night. A vague feeling of

impending misfortune impressed me. My sister and I, you will recollect, were twins, and

you know how subtle are the links which bind two souls which are so closely allied. It was

a wild night. The wind was howling outside, and the rain was beating and splashing against

the windows. Suddenly, amid all the hubbub of the gale, there burst forth the wild scream

of a terrified woman. I knew that it was my sister’s voice. I sprang from my bed,

wrapped a shawl round me, and rushed into the corridor. As I [262] opened my door I seemed to hear a low whistle, such as

my sister described, and a few moments later a clanging sound, as if a mass of metal had

fallen. As I ran down the passage, my sister’s door was unlocked, and revolved slowly

upon its hinges. I stared at it horror-stricken, not knowing what was about to issue from

it. By the light of the corridor-lamp I saw my sister appear at the opening, her face

blanched with terror, her hands groping for help, her whole figure swaying to and fro like

that of a drunkard. I ran to her and threw my arms round her, but at that moment her knees

seemed to give way and she fell to the ground. She writhed as one who is in terrible pain,

and her limbs were dreadfully convulsed. At first I thought that she had not recognized

me, but as I bent over her she suddenly shrieked out in a voice which I shall never

forget, ‘Oh, my God! Helen! It was the band! The speckled band!’ There was

something else which she would fain have said, and she stabbed with her finger into the

air in the direction of the doctor’s room, but a fresh convulsion seized her and

choked her words. I rushed out, calling loudly for my stepfather, and I met him hastening

from his room in his dressing-gown. When he reached my sister’s side she was

unconscious, and though he poured brandy down her throat and sent for medical aid from the

village, all efforts were in vain, for she slowly sank and died without having recovered

her consciousness. Such was the dreadful end of my beloved sister.”

“One moment,” said Holmes; “are you sure

about this whistle and metallic sound? Could you swear to it?” “One moment,” said Holmes; “are you sure

about this whistle and metallic sound? Could you swear to it?”

“That was what the county coroner asked me at the

inquiry. It is my strong impression that I heard it, and yet, among the crash of the gale

and the creaking of an old house, I may possibly have been deceived.” “That was what the county coroner asked me at the

inquiry. It is my strong impression that I heard it, and yet, among the crash of the gale

and the creaking of an old house, I may possibly have been deceived.”

“Was your sister dressed?” “Was your sister dressed?”

“No, she was in her night-dress. In her right hand was

found the charred stump of a match, and in her left a match-box.” “No, she was in her night-dress. In her right hand was

found the charred stump of a match, and in her left a match-box.”

“Showing that she had struck a light and looked about her

when the alarm took place. That is important. And what conclusions did the coroner come

to?” “Showing that she had struck a light and looked about her

when the alarm took place. That is important. And what conclusions did the coroner come

to?”

“He investigated the case with great care, for Dr.

Roylott’s conduct had long been notorious in the county, but he was unable to find

any satisfactory cause of death. My evidence showed that the door had been fastened upon

the inner side, and the windows were blocked by old-fashioned shutters with broad iron

bars, which were secured every night. The walls were carefully sounded, and were shown to

be quite solid all round, and the flooring was also thoroughly examined, with the same

result. The chimney is wide, but is barred up by four large staples. It is certain,

therefore, that my sister was quite alone when she met her end. Besides, there were no

marks of any violence upon her.” “He investigated the case with great care, for Dr.

Roylott’s conduct had long been notorious in the county, but he was unable to find

any satisfactory cause of death. My evidence showed that the door had been fastened upon

the inner side, and the windows were blocked by old-fashioned shutters with broad iron

bars, which were secured every night. The walls were carefully sounded, and were shown to

be quite solid all round, and the flooring was also thoroughly examined, with the same

result. The chimney is wide, but is barred up by four large staples. It is certain,

therefore, that my sister was quite alone when she met her end. Besides, there were no

marks of any violence upon her.”

“How about poison?” “How about poison?”

“The doctors examined her for it, but without

success.” “The doctors examined her for it, but without

success.”

“What do you think that this unfortunate lady died of,

then?” “What do you think that this unfortunate lady died of,

then?”

“It is my belief that she died of pure fear and nervous

shock, though what it was that frightened her I cannot imagine.” “It is my belief that she died of pure fear and nervous

shock, though what it was that frightened her I cannot imagine.”

“Were there gypsies in the plantation at the time?” “Were there gypsies in the plantation at the time?”

“Yes, there are nearly always some there.” “Yes, there are nearly always some there.”

“Ah, and what did you gather from this allusion to a

band–a speckled band?” “Ah, and what did you gather from this allusion to a

band–a speckled band?”

“Sometimes I have thought that it was merely the wild

talk of delirium, sometimes that it may have referred to some band of people, perhaps to

these very gypsies in the plantation. I do not know whether the spotted handkerchiefs

which [263] so many of them

wear over their heads might have suggested the strange adjective which she used.” “Sometimes I have thought that it was merely the wild

talk of delirium, sometimes that it may have referred to some band of people, perhaps to

these very gypsies in the plantation. I do not know whether the spotted handkerchiefs

which [263] so many of them

wear over their heads might have suggested the strange adjective which she used.”

Holmes shook his head like a man who is far from being

satisfied. Holmes shook his head like a man who is far from being

satisfied.

“These are very deep waters,” said he; “pray go

on with your narrative.” “These are very deep waters,” said he; “pray go

on with your narrative.”

“Two years have passed since then, and my life has been

until lately lonelier than ever. A month ago, however, a dear friend, whom I have known

for many years, has done me the honour to ask my hand in marriage. His name is

Armitage–Percy Armitage–the second son of Mr. Armitage, of Crane Water, near

Reading. My stepfather has offered no opposition to the match, and we are to be married in

the course of the spring. Two days ago some repairs were started in the west wing of the

building, and my bedroom wall has been pierced, so that I have had to move into the

chamber in which my sister died, and to sleep in the very bed in which she slept. Imagine,

then, my thrill of terror when last night, as I lay awake, thinking over her terrible

fate, I suddenly heard in the silence of the night the low whistle which had been the

herald of her own death. I sprang up and lit the lamp, but nothing was to be seen in the

room. I was too shaken to go to bed again, however, so I dressed, and as soon as it was

daylight I slipped down, got a dog-cart at the Crown Inn, which is opposite, and drove to

Leatherhead, from whence I have come on this morning with the one object of seeing you and

asking your advice.” “Two years have passed since then, and my life has been

until lately lonelier than ever. A month ago, however, a dear friend, whom I have known

for many years, has done me the honour to ask my hand in marriage. His name is

Armitage–Percy Armitage–the second son of Mr. Armitage, of Crane Water, near

Reading. My stepfather has offered no opposition to the match, and we are to be married in

the course of the spring. Two days ago some repairs were started in the west wing of the

building, and my bedroom wall has been pierced, so that I have had to move into the

chamber in which my sister died, and to sleep in the very bed in which she slept. Imagine,

then, my thrill of terror when last night, as I lay awake, thinking over her terrible

fate, I suddenly heard in the silence of the night the low whistle which had been the

herald of her own death. I sprang up and lit the lamp, but nothing was to be seen in the

room. I was too shaken to go to bed again, however, so I dressed, and as soon as it was

daylight I slipped down, got a dog-cart at the Crown Inn, which is opposite, and drove to

Leatherhead, from whence I have come on this morning with the one object of seeing you and

asking your advice.”

“You have done wisely,” said my friend. “But

have you told me all?” “You have done wisely,” said my friend. “But

have you told me all?”

“Yes, all.” “Yes, all.”

“Miss Roylott, you have not. You are screening your

stepfather.” “Miss Roylott, you have not. You are screening your

stepfather.”

“Why, what do you mean?” “Why, what do you mean?”

For answer Holmes pushed back the frill of black lace which

fringed the hand that lay upon our visitor’s knee. Five little livid spots, the marks

of four fingers and a thumb, were printed upon the white wrist. For answer Holmes pushed back the frill of black lace which

fringed the hand that lay upon our visitor’s knee. Five little livid spots, the marks

of four fingers and a thumb, were printed upon the white wrist.

“You have been cruelly used,” said Holmes. “You have been cruelly used,” said Holmes.

The lady coloured deeply and covered over her injured wrist.

“He is a hard man,” she said, “and perhaps he hardly knows his own

strength.” The lady coloured deeply and covered over her injured wrist.

“He is a hard man,” she said, “and perhaps he hardly knows his own

strength.”

There was a long silence, during which Holmes leaned his chin

upon his hands and stared into the crackling fire. There was a long silence, during which Holmes leaned his chin

upon his hands and stared into the crackling fire.

“This is a very deep business,” he said at last.

“There are a thousand details which I should desire to know before I decide upon our

course of action. Yet we have not a moment to lose. If we were to come to Stoke Moran

to-day, would it be possible for us to see over these rooms without the knowledge of your

stepfather?” “This is a very deep business,” he said at last.

“There are a thousand details which I should desire to know before I decide upon our

course of action. Yet we have not a moment to lose. If we were to come to Stoke Moran

to-day, would it be possible for us to see over these rooms without the knowledge of your

stepfather?”

“As it happens, he spoke of coming into town to-day upon

some most important business. It is probable that he will be away all day, and that there

would be nothing to disturb you. We have a housekeeper now, but she is old and foolish,

and I could easily get her out of the way.” “As it happens, he spoke of coming into town to-day upon

some most important business. It is probable that he will be away all day, and that there

would be nothing to disturb you. We have a housekeeper now, but she is old and foolish,

and I could easily get her out of the way.”

“Excellent. You are not averse to this trip,

Watson?” “Excellent. You are not averse to this trip,

Watson?”

“By no means.” “By no means.”

“Then we shall both come. What are you going to do

yourself?” “Then we shall both come. What are you going to do

yourself?”

“I have one or two things which I would wish to do now

that I am in town. But I shall return by the twelve o’clock train, so as to be there

in time for your coming.” “I have one or two things which I would wish to do now

that I am in town. But I shall return by the twelve o’clock train, so as to be there

in time for your coming.”

“And you may expect us early in the afternoon. I have

myself some small business matters to attend to. Will you not wait and breakfast?” “And you may expect us early in the afternoon. I have

myself some small business matters to attend to. Will you not wait and breakfast?”

[264] “No,

I must go. My heart is lightened already since I have confided my trouble to you. I shall

look forward to seeing you again this afternoon.” She dropped her thick black veil

over her face and glided from the room. [264] “No,

I must go. My heart is lightened already since I have confided my trouble to you. I shall

look forward to seeing you again this afternoon.” She dropped her thick black veil

over her face and glided from the room.

“And what do you think of it all, Watson?” asked

Sherlock Holmes, leaning back in his chair. “And what do you think of it all, Watson?” asked

Sherlock Holmes, leaning back in his chair.

“It seems to me to be a most dark and sinister

business.” “It seems to me to be a most dark and sinister

business.”

“Dark enough and sinister enough.” “Dark enough and sinister enough.”

“Yet if the lady is correct in saying that the flooring

and walls are sound, and that the door, window, and chimney are impassable, then her

sister must have been undoubtedly alone when she met her mysterious end.” “Yet if the lady is correct in saying that the flooring

and walls are sound, and that the door, window, and chimney are impassable, then her

sister must have been undoubtedly alone when she met her mysterious end.”

“What becomes, then, of these nocturnal whistles, and

what of the very peculiar words of the dying woman?” “What becomes, then, of these nocturnal whistles, and

what of the very peculiar words of the dying woman?”

“I cannot think.” “I cannot think.”

“When you combine the ideas of whistles at night, the

presence of a band of gypsies who are on intimate terms with this old doctor, the fact

that we have every reason to believe that the doctor has an interest in preventing his

stepdaughter’s marriage, the dying allusion to a band, and, finally, the fact that

Miss Helen Stoner heard a metallic clang, which might have been caused by one of those

metal bars that secured the shutters falling back into its place, I think that there is

good ground to think that the mystery may be cleared along those lines.” “When you combine the ideas of whistles at night, the

presence of a band of gypsies who are on intimate terms with this old doctor, the fact

that we have every reason to believe that the doctor has an interest in preventing his

stepdaughter’s marriage, the dying allusion to a band, and, finally, the fact that

Miss Helen Stoner heard a metallic clang, which might have been caused by one of those

metal bars that secured the shutters falling back into its place, I think that there is

good ground to think that the mystery may be cleared along those lines.”

“But what, then, did the gypsies do?” “But what, then, did the gypsies do?”

“I cannot imagine.” “I cannot imagine.”

“I see many objections to any such theory.” “I see many objections to any such theory.”

“And so do I. It is precisely for that reason that we are

going to Stoke Moran this day. I want to see whether the objections are fatal, or if they

may be explained away. But what in the name of the devil!” “And so do I. It is precisely for that reason that we are

going to Stoke Moran this day. I want to see whether the objections are fatal, or if they

may be explained away. But what in the name of the devil!”

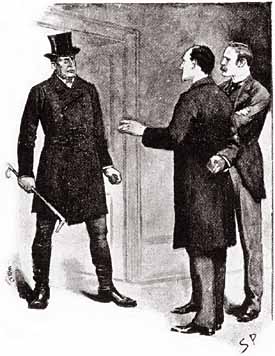

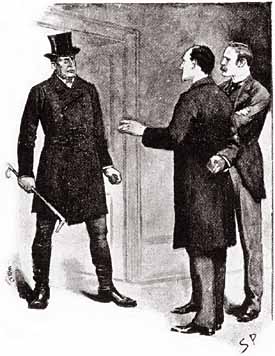

The ejaculation had been drawn from my companion by the fact

that our door had been suddenly dashed open, and that a huge man had framed himself in the

aperture. His costume was a peculiar mixture of the professional and of the agricultural,

having a black top-hat, a long frock-coat, and a pair of high gaiters, with a hunting-crop

swinging in his hand. So tall was he that his hat actually brushed the cross bar of the

doorway, and his breadth seemed to span it across from side to side. A large face, seared

with a thousand wrinkles, burned yellow with the sun, and marked with every evil passion,

was turned from one to the other of us, while his deep-set, bile-shot eyes, and his high,

thin, fleshless nose, gave him somewhat the resemblance to a fierce old bird of prey. The ejaculation had been drawn from my companion by the fact

that our door had been suddenly dashed open, and that a huge man had framed himself in the

aperture. His costume was a peculiar mixture of the professional and of the agricultural,

having a black top-hat, a long frock-coat, and a pair of high gaiters, with a hunting-crop

swinging in his hand. So tall was he that his hat actually brushed the cross bar of the

doorway, and his breadth seemed to span it across from side to side. A large face, seared

with a thousand wrinkles, burned yellow with the sun, and marked with every evil passion,

was turned from one to the other of us, while his deep-set, bile-shot eyes, and his high,

thin, fleshless nose, gave him somewhat the resemblance to a fierce old bird of prey.

“Which of you is Holmes?” asked this apparition. “Which of you is Holmes?” asked this apparition.

“My name, sir; but you have the advantage of me,”

said my companion quietly. “My name, sir; but you have the advantage of me,”

said my companion quietly.

“I am Dr. Grimesby Roylott, of Stoke Moran.” “I am Dr. Grimesby Roylott, of Stoke Moran.”

“Indeed, Doctor,” said Holmes blandly. “Pray

take a seat.” “Indeed, Doctor,” said Holmes blandly. “Pray

take a seat.”

“I will do nothing of the kind. My stepdaughter has been

here. I have traced her. What has she been saying to you?” “I will do nothing of the kind. My stepdaughter has been

here. I have traced her. What has she been saying to you?”

“It is a little cold for the time of the year,” said

Holmes. “It is a little cold for the time of the year,” said

Holmes.

“What has she been saying to you?” screamed the old

man furiously. “What has she been saying to you?” screamed the old

man furiously.

“But I have heard that the crocuses promise well,”

continued my companion imperturbably. “But I have heard that the crocuses promise well,”

continued my companion imperturbably.

“Ha! You put me off, do you?” said our new visitor,

taking a step forward and shaking his hunting-crop. “I know you, you scoundrel! I

have heard of you before. You are Holmes, the meddler.” “Ha! You put me off, do you?” said our new visitor,

taking a step forward and shaking his hunting-crop. “I know you, you scoundrel! I

have heard of you before. You are Holmes, the meddler.”

[265] My

friend smiled. [265] My

friend smiled.

“Holmes, the busybody!” “Holmes, the busybody!”

His smile broadened. His smile broadened.

“Holmes, the Scotland Yard Jack-in-office!” “Holmes, the Scotland Yard Jack-in-office!”

Holmes chuckled heartily. “Your conversation is most

entertaining,” said he. “When you go out close the door, for there is a decided

draught.” Holmes chuckled heartily. “Your conversation is most

entertaining,” said he. “When you go out close the door, for there is a decided

draught.”

“I will go when I have said my say. Don’t you dare

to meddle with my affairs. I know that Miss Stoner has been here. I traced her! I am a

dangerous man to fall foul of! See here.” He stepped swiftly forward, seized the

poker, and bent it into a curve with his huge brown hands. “I will go when I have said my say. Don’t you dare

to meddle with my affairs. I know that Miss Stoner has been here. I traced her! I am a

dangerous man to fall foul of! See here.” He stepped swiftly forward, seized the

poker, and bent it into a curve with his huge brown hands.

“See that you keep yourself out of my grip,” he

snarled, and hurling the twisted poker into the fireplace he strode out of the room. “See that you keep yourself out of my grip,” he

snarled, and hurling the twisted poker into the fireplace he strode out of the room.

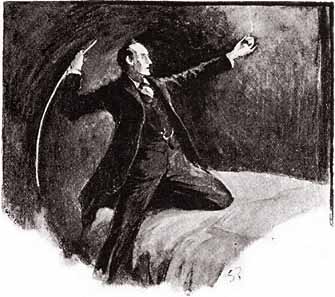

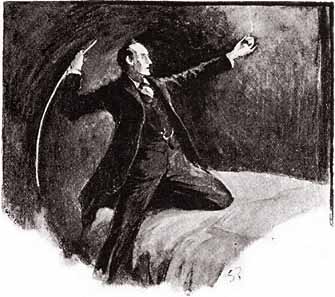

“He seems a very amiable person,” said Holmes,

laughing. “I am not quite so bulky, but if he had remained I might have shown him

that my grip was not much more feeble than his own.” As he spoke he picked up the

steel poker and, with a sudden effort, straightened it out again. “He seems a very amiable person,” said Holmes,

laughing. “I am not quite so bulky, but if he had remained I might have shown him

that my grip was not much more feeble than his own.” As he spoke he picked up the

steel poker and, with a sudden effort, straightened it out again.

“Fancy his having the insolence to confound me with the

official detective force! This incident gives zest to our investigation, however, and I

only trust that our little friend will not suffer from her imprudence in allowing this

brute to trace her. And now, Watson, we shall order breakfast, and afterwards I shall walk

down to Doctors’ Commons, where I hope to get some data which may help us in this

matter.” “Fancy his having the insolence to confound me with the

official detective force! This incident gives zest to our investigation, however, and I

only trust that our little friend will not suffer from her imprudence in allowing this

brute to trace her. And now, Watson, we shall order breakfast, and afterwards I shall walk

down to Doctors’ Commons, where I hope to get some data which may help us in this

matter.”

It was nearly one o’clock when Sherlock Holmes

returned from his excursion. He held in his hand a sheet of blue paper, scrawled over with

notes and figures. It was nearly one o’clock when Sherlock Holmes

returned from his excursion. He held in his hand a sheet of blue paper, scrawled over with

notes and figures.

“I have seen the will of the deceased wife,” said

he. “To determine its exact meaning I have been obliged to work out the present

prices of the investments with which it is concerned. The total income, which at the time

of the wife’s death was little short of ´┐Ż1100, is now, through the fall in

agricultural prices, not more than ´┐Ż750. Each daughter can claim an income of ´┐Ż250, in

case of marriage. It is evident, therefore, that if both girls had married, this beauty

would have had a mere pittance, while even one of them would cripple him to a very serious

extent. My morning’s work has not been wasted, since it has proved that he has the

very strongest motives for standing in the way of anything of the sort. And now, Watson,

this is too serious for dawdling, especially as the old man is aware that we are

interesting ourselves in his affairs; so if you are ready, we shall call a cab and drive

to Waterloo. I should be very much obliged if you would slip your revolver into your

pocket. An Eley’s No. 2 is an excellent argument with gentlemen who can twist steel

pokers into knots. That and a tooth-brush are, I think, all that we need.” “I have seen the will of the deceased wife,” said

he. “To determine its exact meaning I have been obliged to work out the present

prices of the investments with which it is concerned. The total income, which at the time

of the wife’s death was little short of ´┐Ż1100, is now, through the fall in

agricultural prices, not more than ´┐Ż750. Each daughter can claim an income of ´┐Ż250, in

case of marriage. It is evident, therefore, that if both girls had married, this beauty

would have had a mere pittance, while even one of them would cripple him to a very serious

extent. My morning’s work has not been wasted, since it has proved that he has the

very strongest motives for standing in the way of anything of the sort. And now, Watson,

this is too serious for dawdling, especially as the old man is aware that we are

interesting ourselves in his affairs; so if you are ready, we shall call a cab and drive

to Waterloo. I should be very much obliged if you would slip your revolver into your

pocket. An Eley’s No. 2 is an excellent argument with gentlemen who can twist steel

pokers into knots. That and a tooth-brush are, I think, all that we need.”

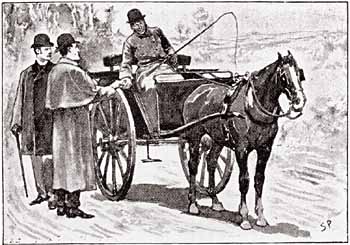

At Waterloo we were fortunate in catching a train for

Leatherhead, where we hired a trap at the station inn and drove for four or five miles

through the lovely Surrey lanes. It was a perfect day, with a bright sun and a few fleecy

clouds in the heavens. The trees and wayside hedges were just throwing out their first

green shoots, and the air was full of the pleasant smell of the moist earth. To me at

least there was a strange contrast between the sweet promise of the spring and this

sinister quest upon which we were engaged. My companion sat in the front of the trap, his

arms folded, his hat pulled down over his eyes, and his chin sunk [266] upon his breast, buried in the

deepest thought. Suddenly, however, he started, tapped me on the shoulder, and pointed

over the meadows. At Waterloo we were fortunate in catching a train for

Leatherhead, where we hired a trap at the station inn and drove for four or five miles

through the lovely Surrey lanes. It was a perfect day, with a bright sun and a few fleecy

clouds in the heavens. The trees and wayside hedges were just throwing out their first

green shoots, and the air was full of the pleasant smell of the moist earth. To me at

least there was a strange contrast between the sweet promise of the spring and this

sinister quest upon which we were engaged. My companion sat in the front of the trap, his

arms folded, his hat pulled down over his eyes, and his chin sunk [266] upon his breast, buried in the

deepest thought. Suddenly, however, he started, tapped me on the shoulder, and pointed

over the meadows.

“Look there!” said he. “Look there!” said he.

A heavily timbered park stretched up in a gentle slope,

thickening into a grove at the highest point. From amid the branches there jutted out the

gray gables and high roof-tree of a very old mansion. A heavily timbered park stretched up in a gentle slope,

thickening into a grove at the highest point. From amid the branches there jutted out the

gray gables and high roof-tree of a very old mansion.

“Stoke Moran?” said he. “Stoke Moran?” said he.

“Yes, sir, that be the house of Dr. Grimesby

Roylott,” remarked the driver. “Yes, sir, that be the house of Dr. Grimesby

Roylott,” remarked the driver.

“There is some building going on there,” said

Holmes; “that is where we are going.” “There is some building going on there,” said

Holmes; “that is where we are going.”

“There’s the village,” said the driver,

pointing to a cluster of roofs some distance to the left; “but if you want to get to

the house, you’ll find it shorter to get over this stile, and so by the foot-path

over the fields. There it is, where the lady is walking.” “There’s the village,” said the driver,

pointing to a cluster of roofs some distance to the left; “but if you want to get to

the house, you’ll find it shorter to get over this stile, and so by the foot-path

over the fields. There it is, where the lady is walking.”

“And the lady, I fancy, is Miss Stoner,” observed

Holmes, shading his eyes. “Yes, I think we had better do as you suggest.” “And the lady, I fancy, is Miss Stoner,” observed

Holmes, shading his eyes. “Yes, I think we had better do as you suggest.”

We got off, paid our fare, and the trap rattled back on its

way to Leatherhead. We got off, paid our fare, and the trap rattled back on its

way to Leatherhead.

“I thought it as well,” said Holmes as we climbed

the stile, “that this fellow should think we had come here as architects, or on some

definite business. It may stop his gossip. Good-afternoon, Miss Stoner. You see that we

have been as good as our word.” “I thought it as well,” said Holmes as we climbed

the stile, “that this fellow should think we had come here as architects, or on some

definite business. It may stop his gossip. Good-afternoon, Miss Stoner. You see that we

have been as good as our word.”

Our client of the morning had hurried forward to meet us with

a face which spoke her joy. “I have been waiting so eagerly for you,” she cried,

shaking hands with us warmly. “All has turned out splendidly. Dr. Roylott has gone to

town, and it is unlikely that he will be back before evening.” Our client of the morning had hurried forward to meet us with

a face which spoke her joy. “I have been waiting so eagerly for you,” she cried,

shaking hands with us warmly. “All has turned out splendidly. Dr. Roylott has gone to

town, and it is unlikely that he will be back before evening.”

“We have had the pleasure of making the doctor’s

acquaintance,” said Holmes, and in a few words he sketched out what had occurred.

Miss Stoner turned white to the lips as she listened. “We have had the pleasure of making the doctor’s

acquaintance,” said Holmes, and in a few words he sketched out what had occurred.

Miss Stoner turned white to the lips as she listened.

“Good heavens!” she cried, “he has followed me,

then.” “Good heavens!” she cried, “he has followed me,

then.”

“So it appears.” “So it appears.”

“He is so cunning that I never know when I am safe from

him. What will he say when he returns?” “He is so cunning that I never know when I am safe from

him. What will he say when he returns?”

“He must guard himself, for he may find that there is

someone more cunning than himself upon his track. You must lock yourself up from him

to-night. If he is violent, we shall take you away to your aunt’s at Harrow. Now, we

must make the best use of our time, so kindly take us at once to the rooms which we are to

examine.” “He must guard himself, for he may find that there is

someone more cunning than himself upon his track. You must lock yourself up from him

to-night. If he is violent, we shall take you away to your aunt’s at Harrow. Now, we

must make the best use of our time, so kindly take us at once to the rooms which we are to

examine.”

The building was of gray, lichen-blotched stone, with a

high central portion and two curving wings, like the claws of a crab, thrown out on each

side. In one of these wings the windows were broken and blocked with wooden boards, while

the roof was partly caved in, a picture of ruin. The central portion was in little better

repair, but the right-hand block was comparatively modern, and the blinds in the windows,

with the blue smoke curling up from the chimneys, showed that this was where the family

resided. Some scaffolding had been erected against the end wall, and the stone-work had

been broken into, but there were no signs of any workmen at the moment of our visit.

Holmes walked slowly up and down the ill-trimmed lawn and examined with deep attention the

outsides of the windows. The building was of gray, lichen-blotched stone, with a

high central portion and two curving wings, like the claws of a crab, thrown out on each

side. In one of these wings the windows were broken and blocked with wooden boards, while

the roof was partly caved in, a picture of ruin. The central portion was in little better

repair, but the right-hand block was comparatively modern, and the blinds in the windows,

with the blue smoke curling up from the chimneys, showed that this was where the family

resided. Some scaffolding had been erected against the end wall, and the stone-work had

been broken into, but there were no signs of any workmen at the moment of our visit.

Holmes walked slowly up and down the ill-trimmed lawn and examined with deep attention the

outsides of the windows.

“This, I take it, belongs to the room in which you used

to sleep, the centre [267] one

to your sister’s, and the one next to the main building to Dr. Roylott’s

chamber?” “This, I take it, belongs to the room in which you used

to sleep, the centre [267] one

to your sister’s, and the one next to the main building to Dr. Roylott’s

chamber?”

“Exactly so. But I am now sleeping in the middle

one.” “Exactly so. But I am now sleeping in the middle

one.”

“Pending the alterations, as I understand. By the way,

there does not seem to be any very pressing need for repairs at that end wall.” “Pending the alterations, as I understand. By the way,

there does not seem to be any very pressing need for repairs at that end wall.”

“There were none. I believe that it was an excuse to move

me from my room.” “There were none. I believe that it was an excuse to move

me from my room.”

“Ah! that is suggestive. Now, on the other side of this

narrow wing runs the corridor from which these three rooms open. There are windows in it,

of course?” “Ah! that is suggestive. Now, on the other side of this

narrow wing runs the corridor from which these three rooms open. There are windows in it,

of course?”

“Yes, but very small ones. Too narrow for anyone to pass

through.” “Yes, but very small ones. Too narrow for anyone to pass

through.”

“As you both locked your doors at night, your rooms were

unapproachable from that side. Now, would you have the kindness to go into your room and

bar your shutters?” “As you both locked your doors at night, your rooms were

unapproachable from that side. Now, would you have the kindness to go into your room and

bar your shutters?”

Miss Stoner did so, and Holmes, after a careful examination

through the open window, endeavoured in every way to force the shutter open, but without

success. There was no slit through which a knife could be passed to raise the bar. Then

with his lens he tested the hinges, but they were of solid iron, built firmly into the

massive masonry. “Hum!” said he, scratching his chin in some perplexity,

“my theory certainly presents some difficulties. No one could pass these shutters if

they were bolted. Well, we shall see if the inside throws any light upon the matter.” Miss Stoner did so, and Holmes, after a careful examination

through the open window, endeavoured in every way to force the shutter open, but without

success. There was no slit through which a knife could be passed to raise the bar. Then

with his lens he tested the hinges, but they were of solid iron, built firmly into the

massive masonry. “Hum!” said he, scratching his chin in some perplexity,

“my theory certainly presents some difficulties. No one could pass these shutters if

they were bolted. Well, we shall see if the inside throws any light upon the matter.”

A small side door led into the whitewashed corridor from which

the three bedrooms opened. Holmes refused to examine the third chamber, so we passed at

once to the second, that in which Miss Stoner was now sleeping, and in which her sister

had met with her fate. It was a homely little room, with a low ceiling and a gaping

fireplace, after the fashion of old country-houses. A brown chest of drawers stood in one

corner, a narrow white-counterpaned bed in another, and a dressing-table on the left-hand

side of the window. These articles, with two small wicker-work chairs, made up all the

furniture in the room save for a square of Wilton carpet in the centre. The boards round

and the panelling of the walls were of brown, worm-eaten oak, so old and discoloured that

it may have dated from the original building of the house. Holmes drew one of the chairs

into a corner and sat silent, while his eyes travelled round and round and up and down,

taking in every detail of the apartment. A small side door led into the whitewashed corridor from which

the three bedrooms opened. Holmes refused to examine the third chamber, so we passed at

once to the second, that in which Miss Stoner was now sleeping, and in which her sister

had met with her fate. It was a homely little room, with a low ceiling and a gaping

fireplace, after the fashion of old country-houses. A brown chest of drawers stood in one

corner, a narrow white-counterpaned bed in another, and a dressing-table on the left-hand

side of the window. These articles, with two small wicker-work chairs, made up all the

furniture in the room save for a square of Wilton carpet in the centre. The boards round

and the panelling of the walls were of brown, worm-eaten oak, so old and discoloured that

it may have dated from the original building of the house. Holmes drew one of the chairs

into a corner and sat silent, while his eyes travelled round and round and up and down,

taking in every detail of the apartment.

“Where does that bell communicate with?” he asked at

last, pointing to a thick bell-rope which hung down beside the bed, the tassel actually

lying upon the pillow. “Where does that bell communicate with?” he asked at

last, pointing to a thick bell-rope which hung down beside the bed, the tassel actually

lying upon the pillow.

“It goes to the housekeeper’s room.” “It goes to the housekeeper’s room.”

“It looks newer than the other things?” “It looks newer than the other things?”

“Yes, it was only put there a couple of years ago.” “Yes, it was only put there a couple of years ago.”

“Your sister asked for it, I suppose?” “Your sister asked for it, I suppose?”

“No, I never heard of her using it. We used always to get

what we wanted for ourselves.” “No, I never heard of her using it. We used always to get

what we wanted for ourselves.”

“Indeed, it seemed unnecessary to put so nice a bell-pull

there. You will excuse me for a few minutes while I satisfy myself as to this floor.”

He threw himself down upon his face with his lens in his hand and crawled swiftly backward

and forward, examining minutely the cracks between the boards. Then he did the same with

the wood-work with which the chamber was panelled. Finally he walked over to the bed and

spent some time in staring at it and in running his eye up and down the wall. Finally he

took the bell-rope in his hand and gave it a brisk tug. “Indeed, it seemed unnecessary to put so nice a bell-pull

there. You will excuse me for a few minutes while I satisfy myself as to this floor.”

He threw himself down upon his face with his lens in his hand and crawled swiftly backward

and forward, examining minutely the cracks between the boards. Then he did the same with

the wood-work with which the chamber was panelled. Finally he walked over to the bed and

spent some time in staring at it and in running his eye up and down the wall. Finally he

took the bell-rope in his hand and gave it a brisk tug.

“Why, it’s a dummy,” said he. “Why, it’s a dummy,” said he.

[268] “Won’t

it ring?” [268] “Won’t

it ring?”

“No, it is not even attached to a wire. This is very

interesting. You can see now that it is fastened to a hook just above where the little

opening for the ventilator is.” “No, it is not even attached to a wire. This is very

interesting. You can see now that it is fastened to a hook just above where the little

opening for the ventilator is.”

“How very absurd! I never noticed that before.” “How very absurd! I never noticed that before.”

“Very strange!” muttered Holmes, pulling at the

rope. “There are one or two very singular points about this room. For example, what a

fool a builder must be to open a ventilator into another room, when, with the same

trouble, he might have communicated with the outside air!” “Very strange!” muttered Holmes, pulling at the

rope. “There are one or two very singular points about this room. For example, what a

fool a builder must be to open a ventilator into another room, when, with the same

trouble, he might have communicated with the outside air!”

“That is also quite modern,” said the lady. “That is also quite modern,” said the lady.

“Done about the same time as the bell-rope?”

remarked Holmes. “Done about the same time as the bell-rope?”

remarked Holmes.

“Yes, there were several little changes carried out about

that time.” “Yes, there were several little changes carried out about

that time.”

“They seem to have been of a most interesting

character–dummy bell-ropes, and ventilators which do not ventilate. With your

permission, Miss Stoner, we shall now carry our researches into the inner apartment.” “They seem to have been of a most interesting

character–dummy bell-ropes, and ventilators which do not ventilate. With your

permission, Miss Stoner, we shall now carry our researches into the inner apartment.”

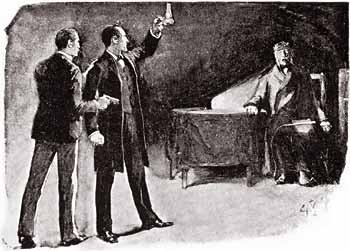

Dr. Grimesby Roylott’s chamber was larger than that of

his stepdaughter, but was as plainly furnished. A camp-bed, a small wooden shelf full of

books, mostly of a technical character, an armchair beside the bed, a plain wooden chair

against the wall, a round table, and a large iron safe were the principal things which met

the eye. Holmes walked slowly round and examined each and all of them with the keenest

interest. Dr. Grimesby Roylott’s chamber was larger than that of

his stepdaughter, but was as plainly furnished. A camp-bed, a small wooden shelf full of

books, mostly of a technical character, an armchair beside the bed, a plain wooden chair

against the wall, a round table, and a large iron safe were the principal things which met

the eye. Holmes walked slowly round and examined each and all of them with the keenest

interest.

“What’s in here?” he asked, tapping the safe. “What’s in here?” he asked, tapping the safe.

“My stepfather’s business papers.” “My stepfather’s business papers.”

“Oh! you have seen inside, then?” “Oh! you have seen inside, then?”

“Only once, some years ago. I remember that it was full

of papers.” “Only once, some years ago. I remember that it was full

of papers.”

“There isn’t a cat in it, for example?” “There isn’t a cat in it, for example?”

“No. What a strange idea!” “No. What a strange idea!”

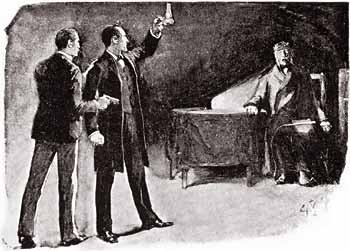

“Well, look at this!” He took up a small saucer of

milk which stood on the top of it. “Well, look at this!” He took up a small saucer of

milk which stood on the top of it.

“No; we don’t keep a cat. But there is a cheetah

and a baboon.” “No; we don’t keep a cat. But there is a cheetah

and a baboon.”

“Ah, yes, of course! Well, a cheetah is just a big cat,

and yet a saucer of milk does not go very far in satisfying its wants, I daresay. There is

one point which I should wish to determine.” He squatted down in front of the wooden

chair and examined the seat of it with the greatest attention. “Ah, yes, of course! Well, a cheetah is just a big cat,

and yet a saucer of milk does not go very far in satisfying its wants, I daresay. There is

one point which I should wish to determine.” He squatted down in front of the wooden

chair and examined the seat of it with the greatest attention.

“Thank you. That is quite settled,” said he, rising

and putting his lens in his pocket. “Hello! Here is something interesting!” “Thank you. That is quite settled,” said he, rising

and putting his lens in his pocket. “Hello! Here is something interesting!”

The object which had caught his eye was a small dog lash hung

on one corner of the bed. The lash, however, was curled upon itself and tied so as to make

a loop of whipcord. The object which had caught his eye was a small dog lash hung

on one corner of the bed. The lash, however, was curled upon itself and tied so as to make

a loop of whipcord.

“What do you make of that, Watson?” “What do you make of that, Watson?”

“It’s a common enough lash. But I don’t know

why it should be tied.” “It’s a common enough lash. But I don’t know

why it should be tied.”

“That is not quite so common, is it? Ah, me! it’s a

wicked world, and when a clever man turns his brains to crime it is the worst of all. I

think that I have seen enough now, Miss Stoner, and with your permission we shall walk out

upon the lawn.” “That is not quite so common, is it? Ah, me! it’s a

wicked world, and when a clever man turns his brains to crime it is the worst of all. I

think that I have seen enough now, Miss Stoner, and with your permission we shall walk out

upon the lawn.”

I had never seen my friend’s face so grim or his brow so

dark as it was when we turned from the scene of this investigation. We had walked several

times up and down the lawn, neither Miss Stoner nor myself liking to break in upon his

thoughts before he roused himself from his reverie. I had never seen my friend’s face so grim or his brow so

dark as it was when we turned from the scene of this investigation. We had walked several

times up and down the lawn, neither Miss Stoner nor myself liking to break in upon his

thoughts before he roused himself from his reverie.

[269] “It

is very essential, Miss Stoner,” said he, “that you should absolutely follow my

advice in every respect.” [269] “It

is very essential, Miss Stoner,” said he, “that you should absolutely follow my

advice in every respect.”

“I shall most certainly do so.” “I shall most certainly do so.”

“The matter is too serious for any hesitation. Your life

may depend upon your compliance.” “The matter is too serious for any hesitation. Your life

may depend upon your compliance.”

“I assure you that I am in your hands.” “I assure you that I am in your hands.”

“In the first place, both my friend and I must spend the

night in your room.” “In the first place, both my friend and I must spend the

night in your room.”

Both Miss Stoner and I gazed at him in astonishment. Both Miss Stoner and I gazed at him in astonishment.

“Yes, it must be so. Let me explain. I believe that that

is the village inn over there?” “Yes, it must be so. Let me explain. I believe that that

is the village inn over there?”

“Yes, that is the Crown.” “Yes, that is the Crown.”

“Very good. Your windows would be visible from

there?” “Very good. Your windows would be visible from

there?”

“Certainly.” “Certainly.”

“You must confine yourself to your room, on pretence of a

headache, when your stepfather comes back. Then when you hear him retire for the night,

you must open the shutters of your window, undo the hasp, put your lamp there as a signal

to us, and then withdraw quietly with everything which you are likely to want into the

room which you used to occupy. I have no doubt that, in spite of the repairs, you could

manage there for one night.” “You must confine yourself to your room, on pretence of a

headache, when your stepfather comes back. Then when you hear him retire for the night,

you must open the shutters of your window, undo the hasp, put your lamp there as a signal

to us, and then withdraw quietly with everything which you are likely to want into the

room which you used to occupy. I have no doubt that, in spite of the repairs, you could

manage there for one night.”

“Oh, yes, easily.” “Oh, yes, easily.”

“The rest you will leave in our hands.” “The rest you will leave in our hands.”

“But what will you do?” “But what will you do?”

“We shall spend the night in your room, and we shall

investigate the cause of this noise which has disturbed you.” “We shall spend the night in your room, and we shall

investigate the cause of this noise which has disturbed you.”

“I believe, Mr. Holmes, that you have already made up

your mind,” said Miss Stoner, laying her hand upon my companion’s sleeve. “I believe, Mr. Holmes, that you have already made up

your mind,” said Miss Stoner, laying her hand upon my companion’s sleeve.

“Perhaps I have.” “Perhaps I have.”

“Then, for pity’s sake, tell me what was the cause

of my sister’s death.” “Then, for pity’s sake, tell me what was the cause

of my sister’s death.”

“I should prefer to have clearer proofs before I

speak.” “I should prefer to have clearer proofs before I

speak.”

“You can at least tell me whether my own thought is

correct, and if she died from some sudden fright.” “You can at least tell me whether my own thought is

correct, and if she died from some sudden fright.”

“No, I do not think so. I think that there was probably

some more tangible cause. And now, Miss Stoner, we must leave you, for if Dr. Roylott

returned and saw us our journey would be in vain. Good-bye, and be brave, for if you will

do what I have told you you may rest assured that we shall soon drive away the dangers

that threaten you.” “No, I do not think so. I think that there was probably

some more tangible cause. And now, Miss Stoner, we must leave you, for if Dr. Roylott

returned and saw us our journey would be in vain. Good-bye, and be brave, for if you will

do what I have told you you may rest assured that we shall soon drive away the dangers

that threaten you.”

Sherlock Holmes and I had no difficulty in engaging a

bedroom and sitting-room at the Crown Inn. They were on the upper floor, and from our

window we could command a view of the avenue gate, and of the inhabited wing of Stoke

Moran Manor House. At dusk we saw Dr. Grimesby Roylott drive past, his huge form looming

up beside the little figure of the lad who drove him. The boy had some slight difficulty

in undoing the heavy iron gates, and we heard the hoarse roar of the doctor’s voice

and saw the fury with which he shook his clinched fists at him. The trap drove on, and a

few minutes later we saw a sudden light spring up among the trees as the lamp was lit in

one of the sitting-rooms. Sherlock Holmes and I had no difficulty in engaging a

bedroom and sitting-room at the Crown Inn. They were on the upper floor, and from our

window we could command a view of the avenue gate, and of the inhabited wing of Stoke

Moran Manor House. At dusk we saw Dr. Grimesby Roylott drive past, his huge form looming

up beside the little figure of the lad who drove him. The boy had some slight difficulty

in undoing the heavy iron gates, and we heard the hoarse roar of the doctor’s voice

and saw the fury with which he shook his clinched fists at him. The trap drove on, and a

few minutes later we saw a sudden light spring up among the trees as the lamp was lit in

one of the sitting-rooms.

“Do you know, Watson,” said Holmes as we sat

together in the gathering darkness, “I have really some scruples as to taking you

to-night. There is a distinct element of danger.” “Do you know, Watson,” said Holmes as we sat

together in the gathering darkness, “I have really some scruples as to taking you

to-night. There is a distinct element of danger.”

“Can I be of assistance?” “Can I be of assistance?”

[270] “Your

presence might be invaluable.” [270] “Your

presence might be invaluable.”

“Then I shall certainly come.” “Then I shall certainly come.”

“It is very kind of you.” “It is very kind of you.”

“You speak of danger. You have evidently seen more in

these rooms than was visible to me.” “You speak of danger. You have evidently seen more in

these rooms than was visible to me.”

“No, but I fancy that I may have deduced a little more. I

imagine that you saw all that I did.” “No, but I fancy that I may have deduced a little more. I

imagine that you saw all that I did.”

“I saw nothing remarkable save the bell-rope, and what

purpose that could answer I confess is more than I can imagine.” “I saw nothing remarkable save the bell-rope, and what

purpose that could answer I confess is more than I can imagine.”

“You saw the ventilator, too?” “You saw the ventilator, too?”

“Yes, but I do not think that it is such a very unusual

thing to have a small opening between two rooms. It was so small that a rat could hardly

pass through.” “Yes, but I do not think that it is such a very unusual