|

|

It chanced that on the same evening McMurdo had another more

pressing interview which urged him in the same direction. It may have been that his

attentions to Ettie had been more evident than before, or that they had gradually obtruded

themselves into the slow mind of his good German host; but, whatever the cause, the

boarding-house keeper beckoned the young man into his private room and started on the

subject without any circumlocution. It chanced that on the same evening McMurdo had another more

pressing interview which urged him in the same direction. It may have been that his

attentions to Ettie had been more evident than before, or that they had gradually obtruded

themselves into the slow mind of his good German host; but, whatever the cause, the

boarding-house keeper beckoned the young man into his private room and started on the

subject without any circumlocution.

“It seems to me, mister,” said he, “that you

are gettin’ set on my Ettie. Ain’t that so, or am I wrong?” “It seems to me, mister,” said he, “that you

are gettin’ set on my Ettie. Ain’t that so, or am I wrong?”

“Yes, that is so,” the young man answered. “Yes, that is so,” the young man answered.

“Vell, I vant to tell you right now that it ain’t no

manner of use. There’s someone slipped in afore you.” “Vell, I vant to tell you right now that it ain’t no

manner of use. There’s someone slipped in afore you.”

“She told me so.” “She told me so.”

“Vell, you can lay that she told you truth. But did she

tell you who it vas?” “Vell, you can lay that she told you truth. But did she

tell you who it vas?”

“No, I asked her; but she wouldn’t tell.” “No, I asked her; but she wouldn’t tell.”

“I dare say not, the leetle baggage! Perhaps she did not

vish to frighten you avay.” “I dare say not, the leetle baggage! Perhaps she did not

vish to frighten you avay.”

“Frighten!” McMurdo was on fire in a moment. “Frighten!” McMurdo was on fire in a moment.

“Ah, yes, my friend! You need not be ashamed to be

frightened of him. It is Teddy Baldwin.” “Ah, yes, my friend! You need not be ashamed to be

frightened of him. It is Teddy Baldwin.”

“And who the devil is he?” “And who the devil is he?”

“He is a boss of Scowrers.” “He is a boss of Scowrers.”

“Scowrers! I’ve heard of them before. It’s

Scowrers here and Scowrers there, and always in a whisper! What are you all afraid of? Who

are the Scowrers?” “Scowrers! I’ve heard of them before. It’s

Scowrers here and Scowrers there, and always in a whisper! What are you all afraid of? Who

are the Scowrers?”

The boarding-house keeper instinctively sank his voice, as

everyone did who talked about that terrible society. “The Scowrers,” said he,

“are the Eminent Order of Freemen!” The boarding-house keeper instinctively sank his voice, as

everyone did who talked about that terrible society. “The Scowrers,” said he,

“are the Eminent Order of Freemen!”

The young man stared. “Why, I am a member of that order

myself.” The young man stared. “Why, I am a member of that order

myself.”

“You! I vould never have had you in my house if I had

known it–not if you vere to pay me a hundred dollar a veek.” “You! I vould never have had you in my house if I had

known it–not if you vere to pay me a hundred dollar a veek.”

“What’s wrong with the order? It’s for charity

and good fellowship. The rules say so.” “What’s wrong with the order? It’s for charity

and good fellowship. The rules say so.”

“Maybe in some places. Not here!” “Maybe in some places. Not here!”

“What is it here?” “What is it here?”

“It’s a murder society, that’s vat it is.” “It’s a murder society, that’s vat it is.”

McMurdo laughed incredulously. “How can you prove

that?” he asked. McMurdo laughed incredulously. “How can you prove

that?” he asked.

“Prove it! Are there not fifty murders to prove it? Vat

about Milman and Van Shorst, and the Nicholson family, and old Mr. Hyam, and little Billy

James, and [823] the others?

Prove it! Is there a man or a voman in this valley vat does not know it?” “Prove it! Are there not fifty murders to prove it? Vat

about Milman and Van Shorst, and the Nicholson family, and old Mr. Hyam, and little Billy

James, and [823] the others?

Prove it! Is there a man or a voman in this valley vat does not know it?”

“See here!” said McMurdo earnestly. “I want you

to take back what you’ve said, or else make it good. One or the other you must do

before I quit this room. Put yourself in my place. Here am I, a stranger in the town. I

belong to a society that I know only as an innocent one. You’ll find it through the

length and breadth of the States; but always as an innocent one. Now, when I am counting

upon joining it here, you tell me that it is the same as a murder society called the

Scowrers. I guess you owe me either an apology or else an explanation, Mr. Shafter.” “See here!” said McMurdo earnestly. “I want you

to take back what you’ve said, or else make it good. One or the other you must do

before I quit this room. Put yourself in my place. Here am I, a stranger in the town. I

belong to a society that I know only as an innocent one. You’ll find it through the

length and breadth of the States; but always as an innocent one. Now, when I am counting

upon joining it here, you tell me that it is the same as a murder society called the

Scowrers. I guess you owe me either an apology or else an explanation, Mr. Shafter.”

“I can but tell you vat the whole vorld knows, mister.

The bosses of the one are the bosses of the other. If you offend the one, it is the other

vat vill strike you. We have proved it too often.” “I can but tell you vat the whole vorld knows, mister.

The bosses of the one are the bosses of the other. If you offend the one, it is the other

vat vill strike you. We have proved it too often.”

“That’s just gossip–I want proof!” said

McMurdo. “That’s just gossip–I want proof!” said

McMurdo.

“If you live here long you vill get your proof. But I

forget that you are yourself one of them. You vill soon be as bad as the rest. But you

vill find other lodgings, mister. I cannot have you here. Is it not bad enough that one of

these people come courting my Ettie, and that I dare not turn him down, but that I should

have another for my boarder? Yes, indeed, you shall not sleep here after to-night!” “If you live here long you vill get your proof. But I

forget that you are yourself one of them. You vill soon be as bad as the rest. But you

vill find other lodgings, mister. I cannot have you here. Is it not bad enough that one of

these people come courting my Ettie, and that I dare not turn him down, but that I should

have another for my boarder? Yes, indeed, you shall not sleep here after to-night!” McMurdo found himself under sentence of banishment both from his

comfortable quarters and from the girl whom he loved. He found her alone in the

sitting-room that same evening, and he poured his troubles into her ear. McMurdo found himself under sentence of banishment both from his

comfortable quarters and from the girl whom he loved. He found her alone in the

sitting-room that same evening, and he poured his troubles into her ear.

“Sure, your father is after giving me notice,” he

said. “It’s little I would care if it was just my room, but indeed, Ettie,

though it’s only a week that I’ve known you, you are the very breath of life to

me, and I can’t live without you!” “Sure, your father is after giving me notice,” he

said. “It’s little I would care if it was just my room, but indeed, Ettie,

though it’s only a week that I’ve known you, you are the very breath of life to

me, and I can’t live without you!”

“Oh, hush, Mr. McMurdo, don’t speak so!” said

the girl. “I have told you, have I not, that you are too late? There is another, and

if I have not promised to marry him at once, at least I can promise no one else.” “Oh, hush, Mr. McMurdo, don’t speak so!” said

the girl. “I have told you, have I not, that you are too late? There is another, and

if I have not promised to marry him at once, at least I can promise no one else.”

“Suppose I had been first, Ettie, would I have had a

chance?” “Suppose I had been first, Ettie, would I have had a

chance?”

The girl sank her face into her hands. “I wish to heaven

that you had been first!” she sobbed. The girl sank her face into her hands. “I wish to heaven

that you had been first!” she sobbed.

McMurdo was down on his knees before her in an instant.

“For God’s sake, Ettie, let it stand at that!” he cried. “Will you

ruin your life and my own for the sake of this promise? Follow your heart, acushla!

’Tis a safer guide than any promise before you knew what it was that you were

saying.” McMurdo was down on his knees before her in an instant.

“For God’s sake, Ettie, let it stand at that!” he cried. “Will you

ruin your life and my own for the sake of this promise? Follow your heart, acushla!

’Tis a safer guide than any promise before you knew what it was that you were

saying.”

He had seized Ettie’s white hand between his own strong

brown ones. He had seized Ettie’s white hand between his own strong

brown ones.

“Say that you will be mine, and we will face it out

together!” “Say that you will be mine, and we will face it out

together!”

“Not here?” “Not here?”

“Yes, here.” “Yes, here.”

“No, no, Jack!” His arms were round her now.

“It could not be here. Could you take me away?” “No, no, Jack!” His arms were round her now.

“It could not be here. Could you take me away?”

A struggle passed for a moment over McMurdo’s face; but

it ended by setting like granite. “No, here,” he said. “I’ll hold you

against the world, Ettie, right here where we are!” A struggle passed for a moment over McMurdo’s face; but

it ended by setting like granite. “No, here,” he said. “I’ll hold you

against the world, Ettie, right here where we are!”

“Why should we not leave together?” “Why should we not leave together?”

“No, Ettie, I can’t leave here.” “No, Ettie, I can’t leave here.”

“But why?” “But why?”

“I’d never hold my head up again if I felt that I

had been driven out. Besides, what is there to be afraid of? Are we not free folks in a

free country? If you love me, and I you, who will dare to come between?” “I’d never hold my head up again if I felt that I

had been driven out. Besides, what is there to be afraid of? Are we not free folks in a

free country? If you love me, and I you, who will dare to come between?”

[824] “You

don’t know, Jack. You’ve been here too short a time. You don’t know this

Baldwin. You don’t know McGinty and his Scowrers.” [824] “You

don’t know, Jack. You’ve been here too short a time. You don’t know this

Baldwin. You don’t know McGinty and his Scowrers.”

“No, I don’t know them, and I don’t fear them,

and I don’t believe in them!” said McMurdo. “I’ve lived among rough

men, my darling, and instead of fearing them it has always ended that they have feared

me–always, Ettie. It’s mad on the face of it! If these men, as your father says,

have done crime after crime in the valley, and if everyone knows them by name, how comes

it that none are brought to justice? You answer me that, Ettie!” “No, I don’t know them, and I don’t fear them,

and I don’t believe in them!” said McMurdo. “I’ve lived among rough

men, my darling, and instead of fearing them it has always ended that they have feared

me–always, Ettie. It’s mad on the face of it! If these men, as your father says,

have done crime after crime in the valley, and if everyone knows them by name, how comes

it that none are brought to justice? You answer me that, Ettie!”

“Because no witness dares to appear against them. He

would not live a month if he did. Also because they have always their own men to swear

that the accused one was far from the scene of the crime. But surely, Jack, you must have

read all this. I had understood that every paper in the United States was writing about

it.” “Because no witness dares to appear against them. He

would not live a month if he did. Also because they have always their own men to swear

that the accused one was far from the scene of the crime. But surely, Jack, you must have

read all this. I had understood that every paper in the United States was writing about

it.”

“Well, I have read something, it is true; but I had

thought it was a story. Maybe these men have some reason in what they do. Maybe they are

wronged and have no other way to help themselves.” “Well, I have read something, it is true; but I had

thought it was a story. Maybe these men have some reason in what they do. Maybe they are

wronged and have no other way to help themselves.”

“Oh, Jack, don’t let me hear you speak so! That is

how he speaks–the other one!” “Oh, Jack, don’t let me hear you speak so! That is

how he speaks–the other one!”

“Baldwin–he speaks like that, does he?” “Baldwin–he speaks like that, does he?”

“And that is why I loathe him so. Oh, Jack, now I can

tell you the truth. I loathe him with all my heart; but I fear him also. I fear him for

myself; but above all I fear him for father. I know that some great sorrow would come upon

us if I dared to say what I really felt. �hat is why I have put him off with

half-promises. It was in real truth our only hope. But if you would fly with me, Jack, we

could take father with us and live forever far from the power of these wicked men.” “And that is why I loathe him so. Oh, Jack, now I can

tell you the truth. I loathe him with all my heart; but I fear him also. I fear him for

myself; but above all I fear him for father. I know that some great sorrow would come upon

us if I dared to say what I really felt. �hat is why I have put him off with

half-promises. It was in real truth our only hope. But if you would fly with me, Jack, we

could take father with us and live forever far from the power of these wicked men.”

Again there was the struggle upon McMurdo’s face, and

again it set like granite. “No harm shall come to you, Ettie–nor to your father

either. As to wicked men, I expect you may find that I am as bad as the worst of them

before we’re through.” Again there was the struggle upon McMurdo’s face, and

again it set like granite. “No harm shall come to you, Ettie–nor to your father

either. As to wicked men, I expect you may find that I am as bad as the worst of them

before we’re through.”

“No, no, Jack! I would trust you anywhere.” “No, no, Jack! I would trust you anywhere.”

McMurdo laughed bitterly. “Good Lord! how little you know

of me! Your innocent soul, my darling, could not even guess what is passing in mine. But,

hullo, who’s the visitor?” McMurdo laughed bitterly. “Good Lord! how little you know

of me! Your innocent soul, my darling, could not even guess what is passing in mine. But,

hullo, who’s the visitor?”

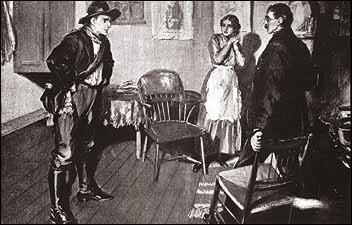

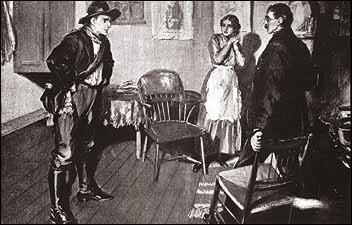

The door had opened suddenly, and a young fellow came

swaggering in with the air of one who is the master. He was a handsome, dashing young man

of about the same age and build as McMurdo himself. Under his broad-brimmed black felt

hat, which he had not troubled to remove, a handsome face with fierce, domineering eyes

and a curved hawk-bill of a nose looked savagely at the pair who sat by the stove. The door had opened suddenly, and a young fellow came

swaggering in with the air of one who is the master. He was a handsome, dashing young man

of about the same age and build as McMurdo himself. Under his broad-brimmed black felt

hat, which he had not troubled to remove, a handsome face with fierce, domineering eyes

and a curved hawk-bill of a nose looked savagely at the pair who sat by the stove.

Ettie had jumped to her feet full of confusion and alarm.

“I’m glad to see you, Mr. Baldwin,” said she. “You’re earlier

than I had thought. Come and sit down.” Ettie had jumped to her feet full of confusion and alarm.

“I’m glad to see you, Mr. Baldwin,” said she. “You’re earlier

than I had thought. Come and sit down.”

Baldwin stood with his hands on his hips looking at McMurdo.

“Who is this?” he asked curtly. Baldwin stood with his hands on his hips looking at McMurdo.

“Who is this?” he asked curtly.

“It’s a friend of mine, Mr. Baldwin, a new boarder

here. Mr. McMurdo, may I introduce you to Mr. Baldwin?” “It’s a friend of mine, Mr. Baldwin, a new boarder

here. Mr. McMurdo, may I introduce you to Mr. Baldwin?”

The young men nodded in surly fashion to each other. The young men nodded in surly fashion to each other.

“Maybe Miss Ettie has told you how it is with us?”

said Baldwin. “Maybe Miss Ettie has told you how it is with us?”

said Baldwin.

“I didn’t understand that there was any relation

between you.” “I didn’t understand that there was any relation

between you.”

“Didn’t you? Well, you can understand it now. You

can take it from me that this young lady is mine, and you’ll find it a very fine

evening for a walk.” “Didn’t you? Well, you can understand it now. You

can take it from me that this young lady is mine, and you’ll find it a very fine

evening for a walk.”

“Thank you, I am in no humour for a walk.” “Thank you, I am in no humour for a walk.”

[825] “Aren’t

you?” The man’s savage eyes were blazing with anger. “Maybe you are in a

humour for a fight, Mr. Boarder!” [825] “Aren’t

you?” The man’s savage eyes were blazing with anger. “Maybe you are in a

humour for a fight, Mr. Boarder!”

“That I am!” cried McMurdo, springing to his

feet. “You never said a more welcome word.” “That I am!” cried McMurdo, springing to his

feet. “You never said a more welcome word.”

“For God’s sake, Jack! Oh, for God’s

sake!” cried poor, distracted Ettie. “Oh, Jack, Jack, he will hurt you!” “For God’s sake, Jack! Oh, for God’s

sake!” cried poor, distracted Ettie. “Oh, Jack, Jack, he will hurt you!”

“Oh, it’s Jack, is it?” said Baldwin with an

oath. “You’ve come to that already, have you?” “Oh, it’s Jack, is it?” said Baldwin with an

oath. “You’ve come to that already, have you?”

“Oh, Ted, be reasonable–be kind! For my sake, Ted,

if ever you loved me, be big-hearted and forgiving!” “Oh, Ted, be reasonable–be kind! For my sake, Ted,

if ever you loved me, be big-hearted and forgiving!”

“I think, Ettie, that if you were to leave us alone we

could get this thing settled,” said McMurdo quietly. “Or maybe, Mr. Baldwin, you

will take a turn down the street with me. It’s a fine evening, and there’s some

open ground beyond the next block.” “I think, Ettie, that if you were to leave us alone we

could get this thing settled,” said McMurdo quietly. “Or maybe, Mr. Baldwin, you

will take a turn down the street with me. It’s a fine evening, and there’s some

open ground beyond the next block.”

“I’ll get even with you without needing to dirty my

hands,” said his enemy. “You’ll wish you had never set foot in this house

before I am through with you!” “I’ll get even with you without needing to dirty my

hands,” said his enemy. “You’ll wish you had never set foot in this house

before I am through with you!”

“No time like the present,” cried McMurdo. “No time like the present,” cried McMurdo.

“I’ll choose my own time, mister. You can leave the

time to me. See here!” He suddenly rolled up his sleeve and showed upon his forearm a

peculiar sign which appeared to have been branded there. It was a circle with a triangle

within it. “D’you know what that means?” “I’ll choose my own time, mister. You can leave the

time to me. See here!” He suddenly rolled up his sleeve and showed upon his forearm a

peculiar sign which appeared to have been branded there. It was a circle with a triangle

within it. “D’you know what that means?”

“I neither know nor care!” “I neither know nor care!”

“Well, you will know, I’ll promise you that. You

won’t be much older, either. Perhaps Miss Ettie can tell you something about it. As

to you, Ettie, you’ll come back to me on your knees–d’ye hear,

girl?–on your knees–and then I’ll tell you what your punishment may be.

You’ve sowed–and by the Lord, I’ll see that you reap!” He glanced at

them both in fury. Then he turned upon his heel, and an instant later the outer door had

banged behind him. “Well, you will know, I’ll promise you that. You

won’t be much older, either. Perhaps Miss Ettie can tell you something about it. As

to you, Ettie, you’ll come back to me on your knees–d’ye hear,

girl?–on your knees–and then I’ll tell you what your punishment may be.

You’ve sowed–and by the Lord, I’ll see that you reap!” He glanced at

them both in fury. Then he turned upon his heel, and an instant later the outer door had

banged behind him.

For a few moments McMurdo and the girl stood in silence. Then

she threw her arms around him. For a few moments McMurdo and the girl stood in silence. Then

she threw her arms around him.

“Oh, Jack, how brave you were! But it is no use, you must

fly! To-night –Jack–to-night! It’s your only hope. He will have your life.

I read it in his horrible eyes. What chance have you against a dozen of them, with Boss

McGinty and all the power of the lodge behind them?” “Oh, Jack, how brave you were! But it is no use, you must

fly! To-night –Jack–to-night! It’s your only hope. He will have your life.

I read it in his horrible eyes. What chance have you against a dozen of them, with Boss

McGinty and all the power of the lodge behind them?”

McMurdo disengaged her hands, kissed her, and gently pushed

her back into a chair. “There, acushla, there! Don’t be disturbed or fear for

me. I’m a Freeman myself. I’m after telling your father about it. Maybe I am no

better than the others; so don’t make a saint of me. Perhaps you hate me too, now

that I’ve told you as much?” McMurdo disengaged her hands, kissed her, and gently pushed

her back into a chair. “There, acushla, there! Don’t be disturbed or fear for

me. I’m a Freeman myself. I’m after telling your father about it. Maybe I am no

better than the others; so don’t make a saint of me. Perhaps you hate me too, now

that I’ve told you as much?”

“Hate you, Jack? While life lasts I could never do that!

I’ve heard that there is no harm in being a Freeman anywhere but here; so why should

I think the worse of you for that? But if you are a Freeman, Jack, why should you not go

down and make a friend of Boss McGinty? Oh, hurry, Jack, hurry! Get your word in first, or

the hounds will be on your trail.” “Hate you, Jack? While life lasts I could never do that!

I’ve heard that there is no harm in being a Freeman anywhere but here; so why should

I think the worse of you for that? But if you are a Freeman, Jack, why should you not go

down and make a friend of Boss McGinty? Oh, hurry, Jack, hurry! Get your word in first, or

the hounds will be on your trail.”

“I was thinking the same thing,” said McMurdo.

“I’ll go right now and fix it. You can tell your father that I’ll sleep

here to-night and find some other quarters in the morning.” “I was thinking the same thing,” said McMurdo.

“I’ll go right now and fix it. You can tell your father that I’ll sleep

here to-night and find some other quarters in the morning.”

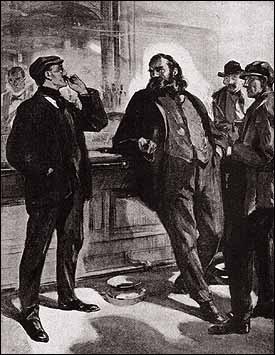

The bar of McGinty’s saloon was crowded as usual; for it

was the favourite loafing place of all the rougher elements of the town. The man was

popular; for he [826] had a

rough, jovial disposition which formed a mask, covering a great deal which lay behind it.

But apart from this popularity, the fear in which he was held throughout the township, and

indeed down the whole thirty miles of the valley and past the mountains on each side of

it, was enough in itself to fill his bar; for none could afford to neglect his good will. The bar of McGinty’s saloon was crowded as usual; for it

was the favourite loafing place of all the rougher elements of the town. The man was

popular; for he [826] had a

rough, jovial disposition which formed a mask, covering a great deal which lay behind it.

But apart from this popularity, the fear in which he was held throughout the township, and

indeed down the whole thirty miles of the valley and past the mountains on each side of

it, was enough in itself to fill his bar; for none could afford to neglect his good will.

Besides those secret powers which it was universally believed

that he exercised in so pitiless a fashion, he was a high public official, a municipal

councillor, and a commissioner of roads, elected to the office through the votes of the

ruffians who in turn expected to receive favours at his hands. Assessments and taxes were

enormous; the public works were notoriously neglected, the accounts were slurred over by

bribed auditors, and the decent citizen was terrorized into paying public blackmail, and

holding his tongue lest some worse thing befall him. Besides those secret powers which it was universally believed

that he exercised in so pitiless a fashion, he was a high public official, a municipal

councillor, and a commissioner of roads, elected to the office through the votes of the

ruffians who in turn expected to receive favours at his hands. Assessments and taxes were

enormous; the public works were notoriously neglected, the accounts were slurred over by

bribed auditors, and the decent citizen was terrorized into paying public blackmail, and

holding his tongue lest some worse thing befall him.

Thus it was that, year by year, Boss McGinty’s diamond

pins became more obtrusive, his gold chains more weighty across a more gorgeous vest, and

his saloon stretched farther and farther, until it threatened to absorb one whole side of

the Market Square. Thus it was that, year by year, Boss McGinty’s diamond

pins became more obtrusive, his gold chains more weighty across a more gorgeous vest, and

his saloon stretched farther and farther, until it threatened to absorb one whole side of

the Market Square.

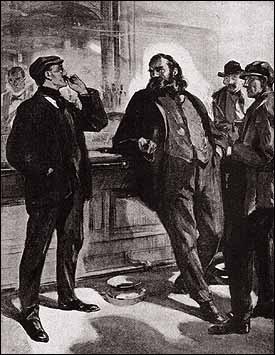

McMurdo pushed open the swinging door of the saloon and made

his way amid the crowd of men within, through an atmosphere blurred with tobacco smoke and

heavy with the smell of spirits. The place was brilliantly lighted, and the huge, heavily

gilt mirrors upon every wall reflected and multiplied the garish illumination. There were

several bartenders in their shirt sleeves, hard at work mixing drinks for the loungers who

fringed the broad, brass-trimmed counter. McMurdo pushed open the swinging door of the saloon and made

his way amid the crowd of men within, through an atmosphere blurred with tobacco smoke and

heavy with the smell of spirits. The place was brilliantly lighted, and the huge, heavily

gilt mirrors upon every wall reflected and multiplied the garish illumination. There were

several bartenders in their shirt sleeves, hard at work mixing drinks for the loungers who

fringed the broad, brass-trimmed counter.

At the far end, with his body resting upon the bar and a cigar

stuck at an acute angle from the corner of his mouth, stood a tall, strong, heavily built

man who could be none other than the famous McGinty himself. He was a black-maned giant,

bearded to the cheek-bones, and with a shock of raven hair which fell to his collar. His

complexion was as swarthy as that of an Italian, and his eyes were of a strange dead

black, which, combined with a slight squint, gave them a particularly sinister appearance. At the far end, with his body resting upon the bar and a cigar

stuck at an acute angle from the corner of his mouth, stood a tall, strong, heavily built

man who could be none other than the famous McGinty himself. He was a black-maned giant,

bearded to the cheek-bones, and with a shock of raven hair which fell to his collar. His

complexion was as swarthy as that of an Italian, and his eyes were of a strange dead

black, which, combined with a slight squint, gave them a particularly sinister appearance.

All else in the man–his noble proportions, his fine

features, and his frank bearing–fitted in with that jovial, man-to-man manner which

he affected. Here, one would say, is a bluff, honest fellow, whose heart would be sound

however rude his outspoken words might seem. It was only when those dead, dark eyes, deep

and remorseless, were turned upon a man that he shrank within himself, feeling that he was

face to face with an infinite possibility of latent evil, with a strength and courage and

cunning behind it which made it a thousand times more deadly. All else in the man–his noble proportions, his fine

features, and his frank bearing–fitted in with that jovial, man-to-man manner which

he affected. Here, one would say, is a bluff, honest fellow, whose heart would be sound

however rude his outspoken words might seem. It was only when those dead, dark eyes, deep

and remorseless, were turned upon a man that he shrank within himself, feeling that he was

face to face with an infinite possibility of latent evil, with a strength and courage and

cunning behind it which made it a thousand times more deadly.

Having had a good look at his man, McMurdo elbowed his way

forward with his usual careless audacity, and pushed himself through the little group of

courtiers who were fawning upon the powerful boss, laughing uproariously at the smallest

of his jokes. The young stranger’s bold gray eyes looked back fearlessly through

their glasses at the deadly black ones which turned sharply upon him. Having had a good look at his man, McMurdo elbowed his way

forward with his usual careless audacity, and pushed himself through the little group of

courtiers who were fawning upon the powerful boss, laughing uproariously at the smallest

of his jokes. The young stranger’s bold gray eyes looked back fearlessly through

their glasses at the deadly black ones which turned sharply upon him.

“Well, young man, I can’t call your face to

mind.” “Well, young man, I can’t call your face to

mind.”

“I’m new here, Mr. McGinty.” “I’m new here, Mr. McGinty.”

“You are not so new that you can’t give a gentleman

his proper title.” “You are not so new that you can’t give a gentleman

his proper title.”

“He’s Councillor McGinty, young man,” said a

voice from the group. “He’s Councillor McGinty, young man,” said a

voice from the group.

“I’m sorry, Councillor. I’m strange to the ways

of the place. But I was advised to see you.” “I’m sorry, Councillor. I’m strange to the ways

of the place. But I was advised to see you.”

“Well, you see me. This is all there is. What d’you

think of me?” “Well, you see me. This is all there is. What d’you

think of me?”

[827] “Well,

it’s early days. If your heart is as big as your body, and your soul as fine as your

face, then I’d ask for nothing better,” said McMurdo. [827] “Well,

it’s early days. If your heart is as big as your body, and your soul as fine as your

face, then I’d ask for nothing better,” said McMurdo.

“By Gar! you’ve got an Irish tongue in your head

anyhow,” cried the saloonkeeper, not quite certain whether to humour this audacious

visitor or to stand upon his dignity. “By Gar! you’ve got an Irish tongue in your head

anyhow,” cried the saloonkeeper, not quite certain whether to humour this audacious

visitor or to stand upon his dignity.

“So you are good enough to pass my appearance?” “So you are good enough to pass my appearance?”

“Sure,” said McMurdo. “Sure,” said McMurdo.

“And you were told to see me?” “And you were told to see me?”

“I was.” “I was.”

“And who told you?” “And who told you?”

“Brother Scanlan of Lodge 341, Vermissa. I drink your

health, Councillor, and to our better acquaintance.” He raised a glass with which he

had been served to his lips and elevated his little finger as he drank it. “Brother Scanlan of Lodge 341, Vermissa. I drink your

health, Councillor, and to our better acquaintance.” He raised a glass with which he

had been served to his lips and elevated his little finger as he drank it.

McGinty, who had been watching him narrowly, raised his thick

black eyebrows. “Oh, it’s like that, is it?” said he. “I’ll have

to look a bit closer into this, Mister– –” McGinty, who had been watching him narrowly, raised his thick

black eyebrows. “Oh, it’s like that, is it?” said he. “I’ll have

to look a bit closer into this, Mister– –”

“McMurdo.” “McMurdo.”

“A bit closer, Mr. McMurdo; for we don’t take folk

on trust in these parts, nor believe all we’re told neither. Come in here for a

moment, behind the bar.” “A bit closer, Mr. McMurdo; for we don’t take folk

on trust in these parts, nor believe all we’re told neither. Come in here for a

moment, behind the bar.”

There was a small room there, lined with barrels. McGinty

carefully closed the door, and then seated himself on one of them, biting thoughtfully on

his cigar and surveying his companion with those disquieting eyes. For a couple of minutes

he sat in complete silence. McMurdo bore the inspection cheerfully, one hand in his coat

pocket, the other twisting his brown moustache. Suddenly McGinty stooped and produced a

wicked-looking revolver. There was a small room there, lined with barrels. McGinty

carefully closed the door, and then seated himself on one of them, biting thoughtfully on

his cigar and surveying his companion with those disquieting eyes. For a couple of minutes

he sat in complete silence. McMurdo bore the inspection cheerfully, one hand in his coat

pocket, the other twisting his brown moustache. Suddenly McGinty stooped and produced a

wicked-looking revolver.

“See here, my joker,” said he, “if I thought

you were playing any game on us, it would be short work for you.” “See here, my joker,” said he, “if I thought

you were playing any game on us, it would be short work for you.”

“This is a strange welcome,” McMurdo answered with

some dignity, “for the Bodymaster of a lodge of Freemen to give to a stranger

brother.” “This is a strange welcome,” McMurdo answered with

some dignity, “for the Bodymaster of a lodge of Freemen to give to a stranger

brother.”

“Ay, but it’s just that same that you have to

prove,” said McGinty, “and God help you if you fail! Where were you made?” “Ay, but it’s just that same that you have to

prove,” said McGinty, “and God help you if you fail! Where were you made?”

“Lodge 29, Chicago.” “Lodge 29, Chicago.”

“When?” “When?”

“June 24, 1872.” “June 24, 1872.”

“What Bodymaster?” “What Bodymaster?”

“James H. Scott.” “James H. Scott.”

“Who is your district ruler?” “Who is your district ruler?”

“Bartholomew Wilson.” “Bartholomew Wilson.”

“Hum! You seem glib enough in your tests. What are you

doing here?” “Hum! You seem glib enough in your tests. What are you

doing here?”

“Working, the same as you–but a poorer job.” “Working, the same as you–but a poorer job.”

“You have your back answer quick enough.” “You have your back answer quick enough.”

“Yes, I was always quick of speech.” “Yes, I was always quick of speech.”

“Are you quick of action?” “Are you quick of action?”

“I have had that name among those that knew me

best.” “I have had that name among those that knew me

best.”

“Well, we may try you sooner than you think. Have you

heard anything of the lodge in these parts?” “Well, we may try you sooner than you think. Have you

heard anything of the lodge in these parts?”

“I’ve heard that it takes a man to be a

brother.” “I’ve heard that it takes a man to be a

brother.”

“True for you, Mr. McMurdo. Why did you leave

Chicago?” “True for you, Mr. McMurdo. Why did you leave

Chicago?”

“I’m damned if I tell you that!” “I’m damned if I tell you that!”

[828] McGinty

opened his eyes. He was not used to being answered in such fashion, and it amused him.

“Why won’t you tell me?” [828] McGinty

opened his eyes. He was not used to being answered in such fashion, and it amused him.

“Why won’t you tell me?”

“Because no brother may tell another a lie.” “Because no brother may tell another a lie.”

“Then the truth is too bad to tell?” “Then the truth is too bad to tell?”

“You can put it that way if you like.” “You can put it that way if you like.”

“See here, mister, you can’t expect me, as

Bodymaster, to pass into the lodge a man for whose past he can’t answer.” “See here, mister, you can’t expect me, as

Bodymaster, to pass into the lodge a man for whose past he can’t answer.”

McMurdo looked puzzled. Then he took a worn newspaper cutting

from an inner pocket. McMurdo looked puzzled. Then he took a worn newspaper cutting

from an inner pocket.

“You wouldn’t squeal on a fellow?” said he. “You wouldn’t squeal on a fellow?” said he.

“I’ll wipe my hand across your face if you say such

words to me!” cried McGinty hotly. “I’ll wipe my hand across your face if you say such

words to me!” cried McGinty hotly.

“You are right, Councillor,” said McMurdo meekly.

“I should apologize. I spoke without thought. Well, I know that I am safe in your

hands. Look at that clipping.” “You are right, Councillor,” said McMurdo meekly.

“I should apologize. I spoke without thought. Well, I know that I am safe in your

hands. Look at that clipping.”

McGinty glanced his eyes over the account of the shooting of

one Jonas Pinto, in the Lake Saloon, Market Street, Chicago, in the New Year week of 1874. McGinty glanced his eyes over the account of the shooting of

one Jonas Pinto, in the Lake Saloon, Market Street, Chicago, in the New Year week of 1874.

“Your work?” he asked, as he handed back the paper. “Your work?” he asked, as he handed back the paper.

McMurdo nodded. McMurdo nodded.

“Why did you shoot him?” “Why did you shoot him?”

“I was helping Uncle Sam to make dollars. Maybe mine were

not as good gold as his, but they looked as well and were cheaper to make. This man Pinto

helped me to shove the queer– –” “I was helping Uncle Sam to make dollars. Maybe mine were

not as good gold as his, but they looked as well and were cheaper to make. This man Pinto

helped me to shove the queer– –”

“To do what?” “To do what?”

“Well, it means to pass the dollars out into circulation.

Then he said he would split. Maybe he did split. I didn’t wait to see. I just killed

him and lighted out for the coal country.” “Well, it means to pass the dollars out into circulation.

Then he said he would split. Maybe he did split. I didn’t wait to see. I just killed

him and lighted out for the coal country.”

“Why the coal country?” “Why the coal country?”

“’Cause I’d read in the papers that they

weren’t too particular in those parts.” “’Cause I’d read in the papers that they

weren’t too particular in those parts.”

McGinty laughed. “You were first a coiner and then a

murderer, and you came to these parts because you thought you’d be welcome.” McGinty laughed. “You were first a coiner and then a

murderer, and you came to these parts because you thought you’d be welcome.”

“That’s about the size of it,” McMurdo

answered. “That’s about the size of it,” McMurdo

answered.

“Well, I guess you’ll go far. Say, can you make

those dollars yet?” “Well, I guess you’ll go far. Say, can you make

those dollars yet?”

McMurdo took half a dozen from his pocket. “Those never

passed the Philadelphia mint,” said he. McMurdo took half a dozen from his pocket. “Those never

passed the Philadelphia mint,” said he.

“You don’t say!” McGinty held them to the light

in his enormous hand, which was hairy as a gorilla’s. “I can see no difference.

Gar! you’ll be a mighty useful brother, I’m thinking! We can do with a bad man

or two among us, Friend McMurdo: for there are times when we have to take our own part.

We’d soon be against the wall if we didn’t shove back at those that were pushing

us.” “You don’t say!” McGinty held them to the light

in his enormous hand, which was hairy as a gorilla’s. “I can see no difference.

Gar! you’ll be a mighty useful brother, I’m thinking! We can do with a bad man

or two among us, Friend McMurdo: for there are times when we have to take our own part.

We’d soon be against the wall if we didn’t shove back at those that were pushing

us.”

“Well, I guess I’ll do my share of shoving with the

rest of the boys.” “Well, I guess I’ll do my share of shoving with the

rest of the boys.”

“You seem to have a good nerve. You didn’t squirm

when I shoved this gun at you.” “You seem to have a good nerve. You didn’t squirm

when I shoved this gun at you.”

“It was not me that was in danger.” “It was not me that was in danger.”

“Who then?” “Who then?”

“It was you, Councillor.” McMurdo drew a cocked

pistol from the side pocket of his pea-jacket. “I was covering you all the time. I

guess my shot would have been as quick as yours.” “It was you, Councillor.” McMurdo drew a cocked

pistol from the side pocket of his pea-jacket. “I was covering you all the time. I

guess my shot would have been as quick as yours.”

“By Gar!” McGinty flushed an angry red and then

burst into a roar of laughter. “Say, we’ve had no such holy terror come to hand

this many a year. I reckon [829] the

lodge will learn to be proud of you. . . . Well, what the hell do you want? And can’t

I speak alone with a gentleman for five minutes but you must butt in on us?” “By Gar!” McGinty flushed an angry red and then

burst into a roar of laughter. “Say, we’ve had no such holy terror come to hand

this many a year. I reckon [829] the

lodge will learn to be proud of you. . . . Well, what the hell do you want? And can’t

I speak alone with a gentleman for five minutes but you must butt in on us?”

The bartender stood abashed. “I’m sorry, Councillor,

but it’s Ted Baldwin. He says he must see you this very minute.” The bartender stood abashed. “I’m sorry, Councillor,

but it’s Ted Baldwin. He says he must see you this very minute.”

The message was unnecessary; for the set, cruel face of the

man himself was looking over the servant’s shoulder. He pushed the bartender out and

closed the door on him. The message was unnecessary; for the set, cruel face of the

man himself was looking over the servant’s shoulder. He pushed the bartender out and

closed the door on him.

“So,” said he with a furious glance at McMurdo,

“you got here first, did you? I’ve a word to say to you, Councillor, about this

man.” “So,” said he with a furious glance at McMurdo,

“you got here first, did you? I’ve a word to say to you, Councillor, about this

man.”

“Then say it here and now before my face,” cried

McMurdo. “Then say it here and now before my face,” cried

McMurdo.

“I’ll say it at my own time, in my own way.” “I’ll say it at my own time, in my own way.”

“Tut! Tut!” said McGinty, getting off his barrel.

“This will never do. We have a new brother here, Baldwin, and it’s not for us to

greet him in such fashion. Hold out your hand, man, and make it up!” “Tut! Tut!” said McGinty, getting off his barrel.

“This will never do. We have a new brother here, Baldwin, and it’s not for us to

greet him in such fashion. Hold out your hand, man, and make it up!”

“Never!” cried Baldwin in a fury. “Never!” cried Baldwin in a fury.

“I’ve offered to fight him if he thinks I have

wronged him,” said McMurdo. “I’ll fight him with fists, or, if that

won’t satisfy him, I’ll fight him any other way he chooses. Now, I’ll leave

it to you, Councillor, to judge between us as a Bodymaster should.” “I’ve offered to fight him if he thinks I have

wronged him,” said McMurdo. “I’ll fight him with fists, or, if that

won’t satisfy him, I’ll fight him any other way he chooses. Now, I’ll leave

it to you, Councillor, to judge between us as a Bodymaster should.”

“What is it, then?” “What is it, then?”

“A young lady. She’s free to choose for

herself.” “A young lady. She’s free to choose for

herself.”

“Is she?” cried Baldwin. “Is she?” cried Baldwin.

“As between two brothers of the lodge I should say that

she was,” said the Boss. “As between two brothers of the lodge I should say that

she was,” said the Boss.

“Oh, that’s your ruling, is it?” “Oh, that’s your ruling, is it?”

“Yes, it is, Ted Baldwin,” said McGinty, with a

wicked stare. “Is it you that would dispute it?” “Yes, it is, Ted Baldwin,” said McGinty, with a

wicked stare. “Is it you that would dispute it?”

“You would throw over one that has stood by you this five

years in favour of a man that you never saw before in your life? You’re not

Bodymaster for life, Jack McGinty, and by God! when next it comes to a vote–

–” “You would throw over one that has stood by you this five

years in favour of a man that you never saw before in your life? You’re not

Bodymaster for life, Jack McGinty, and by God! when next it comes to a vote–

–”

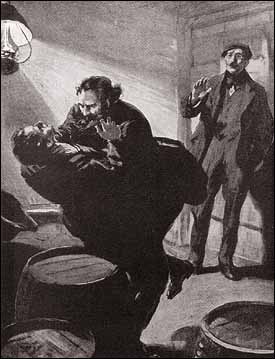

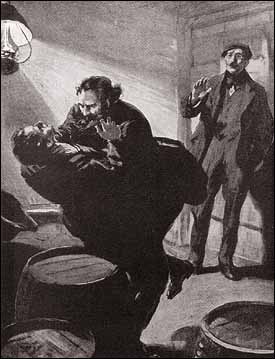

The Councillor sprang at him like a tiger. His hand closed

round the other’s neck, and he hurled him back across one of the barrels. In his mad

fury he would have squeezed the life out of him if McMurdo had not interfered. The Councillor sprang at him like a tiger. His hand closed

round the other’s neck, and he hurled him back across one of the barrels. In his mad

fury he would have squeezed the life out of him if McMurdo had not interfered.

“Easy, Councillor! For heaven’s sake, go

easy!” he cried, as he dragged him back. “Easy, Councillor! For heaven’s sake, go

easy!” he cried, as he dragged him back.

McGinty released his hold, and Baldwin, cowed and shaken,

gasping for breath, and shivering in every limb, as one who has looked over the very edge

of death, sat up on the barrel over which he had been hurled. McGinty released his hold, and Baldwin, cowed and shaken,

gasping for breath, and shivering in every limb, as one who has looked over the very edge

of death, sat up on the barrel over which he had been hurled.

“You’ve been asking for it this many a day, Ted

Baldwin–now you’ve got it!” cried McGinty, his huge chest rising and

falling. “Maybe you think if I was voted down from Bodymaster you would find yourself

in my shoes. It’s for the lodge to say that. But so long as I am the chief I’ll

have no man lift his voice against me or my rulings.” “You’ve been asking for it this many a day, Ted

Baldwin–now you’ve got it!” cried McGinty, his huge chest rising and

falling. “Maybe you think if I was voted down from Bodymaster you would find yourself

in my shoes. It’s for the lodge to say that. But so long as I am the chief I’ll

have no man lift his voice against me or my rulings.”

“I have nothing against you,” mumbled Baldwin,

feeling his throat. “I have nothing against you,” mumbled Baldwin,

feeling his throat.

“Well, then,” cried the other, relapsing in a moment

into a bluff joviality, “we are all good friends again and there’s an end of the

matter.” “Well, then,” cried the other, relapsing in a moment

into a bluff joviality, “we are all good friends again and there’s an end of the

matter.”

He took a bottle of champagne down from the shelf and twisted

out the cork. He took a bottle of champagne down from the shelf and twisted

out the cork.

“See now,” he continued, as he filled three high

glasses. “Let us drink the quarrelling toast of the lodge. After that, as you know,

there can be no bad blood between us. Now, then, the left hand on the apple of my throat.

I say to you, Ted Baldwin, what is the offense, sir?” “See now,” he continued, as he filled three high

glasses. “Let us drink the quarrelling toast of the lodge. After that, as you know,

there can be no bad blood between us. Now, then, the left hand on the apple of my throat.

I say to you, Ted Baldwin, what is the offense, sir?”

[830] “The

clouds are heavy,” answered Baldwin. [830] “The

clouds are heavy,” answered Baldwin.

“But they will forever brighten.” “But they will forever brighten.”

“And this I swear!” “And this I swear!”

The men drank their glasses, and the same ceremony was

performed between Baldwin and McMurdo. The men drank their glasses, and the same ceremony was

performed between Baldwin and McMurdo.

“There!” cried McGinty, rubbing his hands.

“That’s the end of the black blood. You come under lodge discipline if it goes

further, and that’s a heavy hand in these parts, as Brother Baldwin knows–and as

you will damn soon find out, Brother McMurdo, if you ask for trouble!” “There!” cried McGinty, rubbing his hands.

“That’s the end of the black blood. You come under lodge discipline if it goes

further, and that’s a heavy hand in these parts, as Brother Baldwin knows–and as

you will damn soon find out, Brother McMurdo, if you ask for trouble!”

“Faith, I’d be slow to do that,” said McMurdo.

He held out his hand to Baldwin. “I’m quick to quarrel and quick to forgive.

It’s my hot Irish blood, they tell me. But it’s over for me, and I bear no

grudge.” “Faith, I’d be slow to do that,” said McMurdo.

He held out his hand to Baldwin. “I’m quick to quarrel and quick to forgive.

It’s my hot Irish blood, they tell me. But it’s over for me, and I bear no

grudge.”

Baldwin had to take the proffered hand; for the baleful eye of

the terrible Boss was upon him. But his sullen face showed how little the words of the

other had moved him. Baldwin had to take the proffered hand; for the baleful eye of

the terrible Boss was upon him. But his sullen face showed how little the words of the

other had moved him.

McGinty clapped them both on the shoulders. “Tut! These

girls! These girls!” he cried. “To think that the same petticoats should come

between two of my boys! It’s the devil’s own luck! Well, it’s the colleen

inside of them that must settle the question; for it’s outside the jurisdiction of a

Bodymaster– and the Lord be praised for that! We have enough on us, without the women

as well. You’ll have to be affiliated to Lodge 341, Brother McMurdo. We have our own

ways and methods, different from Chicago. Saturday night is our meeting, and if you come

then, we’ll make you free forever of the Vermissa Valley.” McGinty clapped them both on the shoulders. “Tut! These

girls! These girls!” he cried. “To think that the same petticoats should come

between two of my boys! It’s the devil’s own luck! Well, it’s the colleen

inside of them that must settle the question; for it’s outside the jurisdiction of a

Bodymaster– and the Lord be praised for that! We have enough on us, without the women

as well. You’ll have to be affiliated to Lodge 341, Brother McMurdo. We have our own

ways and methods, different from Chicago. Saturday night is our meeting, and if you come

then, we’ll make you free forever of the Vermissa Valley.”

|

![]() And yet he showed again and again, as he had shown in the

railway carriage, [821] a

capacity for sudden, fierce anger, which compelled the respect and even the fear of those

who met him. For the law, too, and all who were connected with it, he exhibited a bitter

contempt which delighted some and alarmed others of his fellow boarders.

And yet he showed again and again, as he had shown in the

railway carriage, [821] a

capacity for sudden, fierce anger, which compelled the respect and even the fear of those

who met him. For the law, too, and all who were connected with it, he exhibited a bitter

contempt which delighted some and alarmed others of his fellow boarders.![]() From the first he made it evident, by his open admiration,

that the daughter of the house had won his heart from the instant that he had set eyes

upon her beauty and her grace. He was no backward suitor. On the second day he told her

that he loved her, and from then onward he repeated the same story with an absolute

disregard of what she might say to discourage him.

From the first he made it evident, by his open admiration,

that the daughter of the house had won his heart from the instant that he had set eyes

upon her beauty and her grace. He was no backward suitor. On the second day he told her

that he loved her, and from then onward he repeated the same story with an absolute

disregard of what she might say to discourage him.![]() “Someone else?” he would cry. “Well, the worse

luck for someone else! Let him look out for himself! Am I to lose my life’s chance

and all my heart’s desire for someone else? You can keep on saying no, Ettie: the day

will come when you will say yes, and I’m young enough to wait.”

“Someone else?” he would cry. “Well, the worse

luck for someone else! Let him look out for himself! Am I to lose my life’s chance

and all my heart’s desire for someone else? You can keep on saying no, Ettie: the day

will come when you will say yes, and I’m young enough to wait.”![]() He was a dangerous suitor, with his glib Irish tongue, and his

pretty, coaxing ways. There was about him also that glamour of experience and of mystery

which attracts a woman’s interest, and finally her love. He could talk of the sweet

valleys of County Monaghan from which he came, of the lovely, distant island, the low

hills and green meadows of which seemed the more beautiful when imagination viewed them

from this place of grime and snow.

He was a dangerous suitor, with his glib Irish tongue, and his

pretty, coaxing ways. There was about him also that glamour of experience and of mystery

which attracts a woman’s interest, and finally her love. He could talk of the sweet

valleys of County Monaghan from which he came, of the lovely, distant island, the low

hills and green meadows of which seemed the more beautiful when imagination viewed them

from this place of grime and snow.![]() Then he was versed in the life of the cities of the North, of

Detroit, and the lumber camps of Michigan, and finally of Chicago, where he had worked in

a planing mill. And afterwards came the hint of romance, the feeling that strange things

had happened to him in that great city, so strange and so intimate that they might not be

spoken of. He spoke wistfully of a sudden leaving, a breaking of old ties, a flight into a

strange world, ending in this dreary valley, and Ettie listened, her dark eyes gleaming

with pity and with sympathy–those two qualities which may turn so rapidly and so

naturally to love.

Then he was versed in the life of the cities of the North, of

Detroit, and the lumber camps of Michigan, and finally of Chicago, where he had worked in

a planing mill. And afterwards came the hint of romance, the feeling that strange things

had happened to him in that great city, so strange and so intimate that they might not be

spoken of. He spoke wistfully of a sudden leaving, a breaking of old ties, a flight into a

strange world, ending in this dreary valley, and Ettie listened, her dark eyes gleaming

with pity and with sympathy–those two qualities which may turn so rapidly and so

naturally to love.![]() McMurdo had obtained a temporary job as bookkeeper; for he

was a well educated man. This kept him out most of the day, and he had not found occasion

yet to report himself to the head of the lodge of the Eminent Order of Freemen. He was

reminded of his omission, however, by a visit one evening from Mike Scanlan, the fellow

member whom he had met in the train. Scanlan, the small, sharp-faced, nervous, black-eyed

man, seemed glad to see him once more. After a glass or two of whisky he broached the

object of his visit.

McMurdo had obtained a temporary job as bookkeeper; for he

was a well educated man. This kept him out most of the day, and he had not found occasion

yet to report himself to the head of the lodge of the Eminent Order of Freemen. He was

reminded of his omission, however, by a visit one evening from Mike Scanlan, the fellow

member whom he had met in the train. Scanlan, the small, sharp-faced, nervous, black-eyed

man, seemed glad to see him once more. After a glass or two of whisky he broached the

object of his visit.![]() “Say, McMurdo,” said he, “I remembered your

address, so I made bold to call. I’m surprised that you’ve not reported to the

Bodymaster. Why haven’t you seen Boss McGinty yet?”

“Say, McMurdo,” said he, “I remembered your

address, so I made bold to call. I’m surprised that you’ve not reported to the

Bodymaster. Why haven’t you seen Boss McGinty yet?”![]() “Well, I had to find a job. I have been busy.”

“Well, I had to find a job. I have been busy.”![]() “You must find time for him if you have none for anything

else. Good Lord, man! you’re a fool not to have been down to the Union House and

registered your name the first morning after you came here! If you run against

him–well, you mustn’t, that’s all!”

“You must find time for him if you have none for anything

else. Good Lord, man! you’re a fool not to have been down to the Union House and

registered your name the first morning after you came here! If you run against

him–well, you mustn’t, that’s all!”![]() McMurdo showed mild surprise. “I’ve been a member of

the lodge for over two years, Scanlan, but I never heard that duties were so pressing as

all that.”

McMurdo showed mild surprise. “I’ve been a member of

the lodge for over two years, Scanlan, but I never heard that duties were so pressing as

all that.”![]() “Maybe not in Chicago.”

“Maybe not in Chicago.”![]() “Well, it’s the same society here.”

“Well, it’s the same society here.”![]() “Is it?”

“Is it?”![]() Scanlan looked at him long and fixedly. There was something

sinister in his eyes.

Scanlan looked at him long and fixedly. There was something

sinister in his eyes.![]() [822] “Isn’t

it?”

[822] “Isn’t

it?”![]() “You’ll tell me that in a month’s time. I hear

you had a talk with the patrolmen after I left the train.”

“You’ll tell me that in a month’s time. I hear

you had a talk with the patrolmen after I left the train.”![]() “How did you know that?”

“How did you know that?”![]() “Oh, it got about–things do get about for good and

for bad in this district.”

“Oh, it got about–things do get about for good and

for bad in this district.”![]() “Well, yes. I told the hounds what I thought of

them.”

“Well, yes. I told the hounds what I thought of

them.”![]() “By the Lord, you’ll be a man after McGinty’s

heart!”

“By the Lord, you’ll be a man after McGinty’s

heart!”![]() “What, does he hate the police too?”

“What, does he hate the police too?”![]() Scanlan burst out laughing. “You go and see him, my

lad,” said he as he took his leave. “It’s not the police but you that

he’ll hate if you don’t! Now, take a friend’s advice and go at once!”

Scanlan burst out laughing. “You go and see him, my

lad,” said he as he took his leave. “It’s not the police but you that

he’ll hate if you don’t! Now, take a friend’s advice and go at once!”