|

|

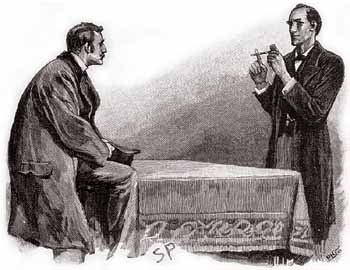

He held it up and tapped on it with his long, thin forefinger,

as a professor might who was lecturing on a bone. He held it up and tapped on it with his long, thin forefinger,

as a professor might who was lecturing on a bone.

“Pipes are occasionally of extraordinary interest,”

said he. “Nothing has more individuality, save perhaps watches and bootlaces. The

indications here, however, are neither very marked nor very important. The owner is

obviously a muscular man, left-handed, with an excellent set of teeth, careless in his

habits, and with no need to practise economy.” “Pipes are occasionally of extraordinary interest,”

said he. “Nothing has more individuality, save perhaps watches and bootlaces. The

indications here, however, are neither very marked nor very important. The owner is

obviously a muscular man, left-handed, with an excellent set of teeth, careless in his

habits, and with no need to practise economy.”

My friend threw out the information in a very offhand way, but

I saw that he cocked his eye at me to see if I had followed his reasoning. My friend threw out the information in a very offhand way, but

I saw that he cocked his eye at me to see if I had followed his reasoning.

“You think a man must be well-to-do if he smokes a

seven-shilling pipe?” said I. “You think a man must be well-to-do if he smokes a

seven-shilling pipe?” said I.

“This is Grosvenor mixture at eightpence an

ounce,” Holmes answered, knocking a little out on his palm. “As he might get an

excellent smoke for half the price, he has no need to practise economy.” “This is Grosvenor mixture at eightpence an

ounce,” Holmes answered, knocking a little out on his palm. “As he might get an

excellent smoke for half the price, he has no need to practise economy.”

“And the other points?” “And the other points?”

“He has been in the habit of lighting his pipe at lamps

and gas-jets. You can see that it is quite charred all down one side. Of course a match

could not have done that. Why should a man hold a match to the side of his pipe? But you

cannot light it at a lamp without getting the bowl charred. And it is all on the right

side of the pipe. From that I gather that he is a left-handed man. You hold your own pipe

to the lamp and see how naturally you, being right-handed, hold the left side to the

flame. You might do it once the other way, but not as a constancy. This has always been

held so. Then he has bitten through his amber. It takes a muscular, energetic fellow, and

one with a good set of teeth, to do that. But if I am not mistaken I hear him upon the

stair, so we shall have something more interesting than his pipe to study.” “He has been in the habit of lighting his pipe at lamps

and gas-jets. You can see that it is quite charred all down one side. Of course a match

could not have done that. Why should a man hold a match to the side of his pipe? But you

cannot light it at a lamp without getting the bowl charred. And it is all on the right

side of the pipe. From that I gather that he is a left-handed man. You hold your own pipe

to the lamp and see how naturally you, being right-handed, hold the left side to the

flame. You might do it once the other way, but not as a constancy. This has always been

held so. Then he has bitten through his amber. It takes a muscular, energetic fellow, and

one with a good set of teeth, to do that. But if I am not mistaken I hear him upon the

stair, so we shall have something more interesting than his pipe to study.”

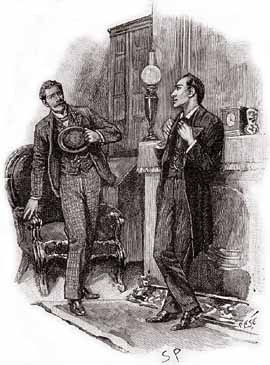

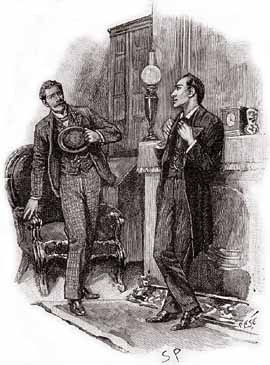

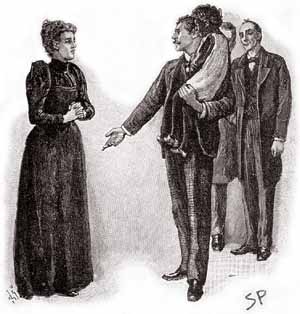

An instant later our door opened, and a tall young man entered

the room. He was well but quietly dressed in a dark gray suit and carried a brown

wideawake in his hand. I should have put him at about thirty, though he was really some

years older. An instant later our door opened, and a tall young man entered

the room. He was well but quietly dressed in a dark gray suit and carried a brown

wideawake in his hand. I should have put him at about thirty, though he was really some

years older.

“I beg your pardon,” said he with some

embarrassment, “I suppose I should have knocked. Yes, of course I should have

knocked. The fact is that I am a little upset, and you must put it all down to that.”

He passed his hand over his forehead like a man who is half dazed, and then fell rather

than sat down upon a chair. “I beg your pardon,” said he with some

embarrassment, “I suppose I should have knocked. Yes, of course I should have

knocked. The fact is that I am a little upset, and you must put it all down to that.”

He passed his hand over his forehead like a man who is half dazed, and then fell rather

than sat down upon a chair.

“I can see that you have not slept for a night or

two,” said Holmes in his easy, genial way. “That tries a man’s nerves more

than work, and more even than pleasure. May I ask how I can help you?” “I can see that you have not slept for a night or

two,” said Holmes in his easy, genial way. “That tries a man’s nerves more

than work, and more even than pleasure. May I ask how I can help you?”

“I wanted your advice, sir. I don’t know what to do,

and my whole life seems to have gone to pieces.” “I wanted your advice, sir. I don’t know what to do,

and my whole life seems to have gone to pieces.”

“You wish to employ me as a consulting detective?” “You wish to employ me as a consulting detective?”

“Not that only. I want your opinion as a judicious

man–as a man of the world. I want to know what I ought to do next. I hope to God

you’ll be able to tell me.” “Not that only. I want your opinion as a judicious

man–as a man of the world. I want to know what I ought to do next. I hope to God

you’ll be able to tell me.”

He spoke in little, sharp, jerky outbursts, and it seemed to

me that to speak at all was very painful to him, and that his will all through was

overriding his inclinations. He spoke in little, sharp, jerky outbursts, and it seemed to

me that to speak at all was very painful to him, and that his will all through was

overriding his inclinations.

[353] “It’s

a very delicate thing,” said he. “One does not like to speak of one’s

domestic affairs to strangers. It seems dreadful to discuss the conduct of one’s wife

with two men whom I have never seen before. It’s horrible to have to do it. But

I’ve got to the end of my tether, and I must have advice.” [353] “It’s

a very delicate thing,” said he. “One does not like to speak of one’s

domestic affairs to strangers. It seems dreadful to discuss the conduct of one’s wife

with two men whom I have never seen before. It’s horrible to have to do it. But

I’ve got to the end of my tether, and I must have advice.”

“My dear Mr. Grant Munro– –” began Holmes. “My dear Mr. Grant Munro– –” began Holmes.

Our visitor sprang from his chair. “What!” he

cried, “you know my name?” Our visitor sprang from his chair. “What!” he

cried, “you know my name?”

“If you wish to preserve your incognito,” said

Holmes, smiling, “I would suggest that you cease to write your name upon the lining

of your hat, or else that you turn the crown towards the person whom you are addressing. I

was about to say that my friend and I have listened to a good many strange secrets in this

room, and that we have had the good fortune to bring peace to many troubled souls. I trust

that we may do as much for you. Might I beg you, as time may prove to be of importance, to

furnish me with the facts of your case without further delay?” “If you wish to preserve your incognito,” said

Holmes, smiling, “I would suggest that you cease to write your name upon the lining

of your hat, or else that you turn the crown towards the person whom you are addressing. I

was about to say that my friend and I have listened to a good many strange secrets in this

room, and that we have had the good fortune to bring peace to many troubled souls. I trust

that we may do as much for you. Might I beg you, as time may prove to be of importance, to

furnish me with the facts of your case without further delay?”

Our visitor again passed his hand over his forehead, as if he

found it bitterly hard. From every gesture and expression I could see that he was a

reserved, self-contained man, with a dash of pride in his nature, more likely to hide his

wounds than to expose them. Then suddenly, with a fierce gesture of his closed hand, like

one who throws reserve to the winds, he began: Our visitor again passed his hand over his forehead, as if he

found it bitterly hard. From every gesture and expression I could see that he was a

reserved, self-contained man, with a dash of pride in his nature, more likely to hide his

wounds than to expose them. Then suddenly, with a fierce gesture of his closed hand, like

one who throws reserve to the winds, he began:

“The facts are these, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “I

am a married man and have been so for three years. During that time my wife and I have

loved each other as fondly and lived as happily as any two that ever were joined. We have

not had a difference, not one, in thought or word or deed. And now, since last Monday,

there has suddenly sprung up a barrier between us, and I find that there is something in

her life and in her thoughts of which I know as little as if she were the woman who

brushes by me in the street. We are estranged, and I want to know why. “The facts are these, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “I

am a married man and have been so for three years. During that time my wife and I have

loved each other as fondly and lived as happily as any two that ever were joined. We have

not had a difference, not one, in thought or word or deed. And now, since last Monday,

there has suddenly sprung up a barrier between us, and I find that there is something in

her life and in her thoughts of which I know as little as if she were the woman who

brushes by me in the street. We are estranged, and I want to know why.

“Now there is one thing that I want to impress upon you

before I go any further, Mr. Holmes. Effie loves me. Don’t let there be any mistake

about that. She loves me with her whole heart and soul, and never more than now. I know

it. I feel it. I don’t want to argue about that. A man can tell easily enough when a

woman loves him. But there’s this secret between us, and we can never be the same

until it is cleared.” “Now there is one thing that I want to impress upon you

before I go any further, Mr. Holmes. Effie loves me. Don’t let there be any mistake

about that. She loves me with her whole heart and soul, and never more than now. I know

it. I feel it. I don’t want to argue about that. A man can tell easily enough when a

woman loves him. But there’s this secret between us, and we can never be the same

until it is cleared.”

“Kindly let me have the facts, Mr. Munro,” said

Holmes with some impatience. “Kindly let me have the facts, Mr. Munro,” said

Holmes with some impatience.

“I’ll tell you what I know about Effie’s

history. She was a widow when I met her first, though quite young–only twenty-five.

Her name then was Mrs. Hebron. She went out to America when she was young and lived in the

town of Atlanta, where she married this Hebron, who was a lawyer with a good practice.

They had one child, but the yellow fever broke out badly in the place, and both husband

and child died of it. I have seen his death certificate. This sickened her of America, and

she came back to live with a maiden aunt at Pinner, in Middlesex. I may mention that her

husband had left her comfortably off, and that she had a capital of about four thousand

five hundred pounds, which had been so well invested by him that it returned an average of

seven per cent. She had only been six months at Pinner when I met her; we fell in love

with each other, and we married a few weeks afterwards. “I’ll tell you what I know about Effie’s

history. She was a widow when I met her first, though quite young–only twenty-five.

Her name then was Mrs. Hebron. She went out to America when she was young and lived in the

town of Atlanta, where she married this Hebron, who was a lawyer with a good practice.

They had one child, but the yellow fever broke out badly in the place, and both husband

and child died of it. I have seen his death certificate. This sickened her of America, and

she came back to live with a maiden aunt at Pinner, in Middlesex. I may mention that her

husband had left her comfortably off, and that she had a capital of about four thousand

five hundred pounds, which had been so well invested by him that it returned an average of

seven per cent. She had only been six months at Pinner when I met her; we fell in love

with each other, and we married a few weeks afterwards.

“I am a hop merchant myself, and as I have an income of

seven or eight hundred, we found ourselves comfortably off and took a nice

eighty-pound-a-year villa at Norbury. Our little place was very countrified, considering

that it is so close to town. We had an inn and two houses a little above us, and a single

cottage at the other side of the field which faces us, and except those there were no

houses until [354] you got

halfway to the station. My business took me into town at certain seasons, but in summer I

had less to do, and then in our country home my wife and I were just as happy as could be

wished. I tell you that there never was a shadow between us until this accursed affair

began. “I am a hop merchant myself, and as I have an income of

seven or eight hundred, we found ourselves comfortably off and took a nice

eighty-pound-a-year villa at Norbury. Our little place was very countrified, considering

that it is so close to town. We had an inn and two houses a little above us, and a single

cottage at the other side of the field which faces us, and except those there were no

houses until [354] you got

halfway to the station. My business took me into town at certain seasons, but in summer I

had less to do, and then in our country home my wife and I were just as happy as could be

wished. I tell you that there never was a shadow between us until this accursed affair

began.

“There’s one thing I ought to tell you before I go

further. When we married, my wife made over all her property to me–rather against my

will, for I saw how awkward it would be if my business affairs went wrong. However, she

would have it so, and it was done. Well, about six weeks ago she came to me. “There’s one thing I ought to tell you before I go

further. When we married, my wife made over all her property to me–rather against my

will, for I saw how awkward it would be if my business affairs went wrong. However, she

would have it so, and it was done. Well, about six weeks ago she came to me.

“ ‘Jack,’ said she, ‘when you took my

money you said that if ever I wanted any I was to ask you for it.’ “ ‘Jack,’ said she, ‘when you took my

money you said that if ever I wanted any I was to ask you for it.’

“ ‘Certainly,’ said I. ‘It’s all your

own.’ “ ‘Certainly,’ said I. ‘It’s all your

own.’

“ ‘Well,’ said she, ‘I want a hundred

pounds.’ “ ‘Well,’ said she, ‘I want a hundred

pounds.’

“I was a bit staggered at this, for I had imagined it was

simply a new dress or something of the kind that she was after. “I was a bit staggered at this, for I had imagined it was

simply a new dress or something of the kind that she was after.

“ ‘What on earth for?’ I asked. “ ‘What on earth for?’ I asked.

“ ‘Oh,’ said she in her playful way, ‘you

said that you were only my banker, and bankers never ask questions, you know.’ “ ‘Oh,’ said she in her playful way, ‘you

said that you were only my banker, and bankers never ask questions, you know.’

“ ‘If you really mean it, of course you shall have

the money,’ said I. “ ‘If you really mean it, of course you shall have

the money,’ said I.

“ ‘Oh, yes, I really mean it.’ “ ‘Oh, yes, I really mean it.’

“ ‘And you won’t tell me what you want it

for?’ “ ‘And you won’t tell me what you want it

for?’

“ ‘Some day, perhaps, but not just at present,

Jack.’ “ ‘Some day, perhaps, but not just at present,

Jack.’

“So I had to be content with that, though it was the

first time that there had ever been any secret between us. I gave her a check, and I never

thought any more of the matter. It may have nothing to do with what came afterwards, but I

thought it only right to mention it. “So I had to be content with that, though it was the

first time that there had ever been any secret between us. I gave her a check, and I never

thought any more of the matter. It may have nothing to do with what came afterwards, but I

thought it only right to mention it.

“Well, I told you just now that there is a cottage not

far from our house. There is just a field between us, but to reach it you have to go along

the road and then turn down a lane. Just beyond it is a nice little grove of Scotch firs,

and I used to be very fond of strolling down there, for trees are always a neighbourly

kind of thing. The cottage had been standing empty this eight months, and it was a pity,

for it was a pretty two-storied place, with an old-fashioned porch and a honeysuckle about

it. I have stood many a time and thought what a neat little homestead it would make. “Well, I told you just now that there is a cottage not

far from our house. There is just a field between us, but to reach it you have to go along

the road and then turn down a lane. Just beyond it is a nice little grove of Scotch firs,

and I used to be very fond of strolling down there, for trees are always a neighbourly

kind of thing. The cottage had been standing empty this eight months, and it was a pity,

for it was a pretty two-storied place, with an old-fashioned porch and a honeysuckle about

it. I have stood many a time and thought what a neat little homestead it would make.

“Well, last Monday evening I was taking a stroll down

that way when I met an empty van coming up the lane and saw a pile of carpets and things

lying about on the grass-plot beside the porch. It was clear that the cottage had at last

been let. I walked past it, and then stopping, as an idle man might, I ran my eye over it

and wondered what sort of folk they were who had come to live so near us. And as I looked

I suddenly became aware that a face was watching me out of one of the upper windows. “Well, last Monday evening I was taking a stroll down

that way when I met an empty van coming up the lane and saw a pile of carpets and things

lying about on the grass-plot beside the porch. It was clear that the cottage had at last

been let. I walked past it, and then stopping, as an idle man might, I ran my eye over it

and wondered what sort of folk they were who had come to live so near us. And as I looked

I suddenly became aware that a face was watching me out of one of the upper windows.

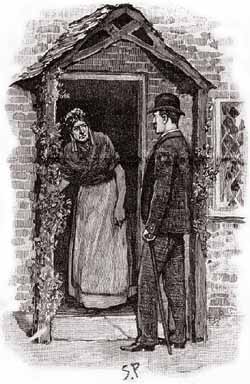

“I don’t know what there was about that face, Mr.

Holmes, but it seemed to send a chill right down my back. I was some little way off, so

that I could not make out the features, but there was something unnatural and inhuman

about the face. That was the impression that I had, and I moved quickly forward to get a

nearer view of the person who was watching me. But as I did so the face suddenly

disappeared, so suddenly that it seemed to have been plucked away into the darkness of the

room. I stood for five minutes thinking the business over and trying to analyze my

impressions. I could not tell if the face was that of a man or a woman. It had been too

far from me for that. But its colour was what had [355] impressed me most. It was of a livid chalky white, and

with something set and rigid about it which was shockingly unnatural. So disturbed was I

that I determined to see a little more of the new inmates of the cottage. I approached and

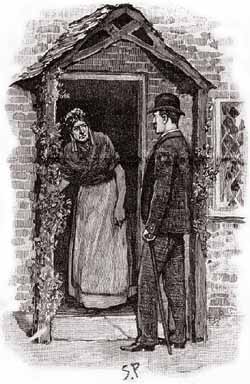

knocked at the door, which was instantly opened by a tall, gaunt woman with a harsh,

forbidding face. “I don’t know what there was about that face, Mr.

Holmes, but it seemed to send a chill right down my back. I was some little way off, so

that I could not make out the features, but there was something unnatural and inhuman

about the face. That was the impression that I had, and I moved quickly forward to get a

nearer view of the person who was watching me. But as I did so the face suddenly

disappeared, so suddenly that it seemed to have been plucked away into the darkness of the

room. I stood for five minutes thinking the business over and trying to analyze my

impressions. I could not tell if the face was that of a man or a woman. It had been too

far from me for that. But its colour was what had [355] impressed me most. It was of a livid chalky white, and

with something set and rigid about it which was shockingly unnatural. So disturbed was I

that I determined to see a little more of the new inmates of the cottage. I approached and

knocked at the door, which was instantly opened by a tall, gaunt woman with a harsh,

forbidding face.

“ ‘What may you be wantin’?’ she asked

in a Northern accent. “ ‘What may you be wantin’?’ she asked

in a Northern accent.

“ ‘I am your neighbour over yonder,’ said I,

nodding towards my house. ‘I see that you have only just moved in, so I thought that

if I could be of any help to you in any– –’ “ ‘I am your neighbour over yonder,’ said I,

nodding towards my house. ‘I see that you have only just moved in, so I thought that

if I could be of any help to you in any– –’

“ ‘Ay, we’ll just ask ye when we want ye,’

said she, and shut the door in my face. Annoyed at the churlish rebuff, I turned my back

and walked home. All evening, though I tried to think of other things, my mind would still

turn to the apparition at the window and the rudeness of the woman. I determined to say

nothing about the former to my wife, for she is a nervous, highly strung woman, and I had

no wish that she should share the unpleasant impression which had been produced upon

myself. I remarked to her, however, before I fell asleep, that the cottage was now

occupied, to which she returned no reply. “ ‘Ay, we’ll just ask ye when we want ye,’

said she, and shut the door in my face. Annoyed at the churlish rebuff, I turned my back

and walked home. All evening, though I tried to think of other things, my mind would still

turn to the apparition at the window and the rudeness of the woman. I determined to say

nothing about the former to my wife, for she is a nervous, highly strung woman, and I had

no wish that she should share the unpleasant impression which had been produced upon

myself. I remarked to her, however, before I fell asleep, that the cottage was now

occupied, to which she returned no reply.

“I am usually an extremely sound sleeper. It has been a

standing jest in the family that nothing could ever wake me during the night. And yet

somehow on that particular night, whether it may have been the slight excitement produced

by my little adventure or not I know not, but I slept much more lightly than usual. Half

in my dreams I was dimly conscious that something was going on in the room, and gradually

became aware that my wife had dressed herself and was slipping on her mantle and her

bonnet. My lips were parted to murmur out some sleepy words of surprise or remonstrance at

this untimely preparation, when suddenly my half-opened eyes fell upon her face,

illuminated by the candle-light, and astonishment held me dumb. She wore an expression

such as I had never seen before–such as I should have thought her incapable of

assuming. She was deadly pale and breathing fast, glancing furtively towards the bed as

she fastened her mantle to see if she had disturbed me. Then, thinking that I was still

asleep, she slipped noiselessly from the room, and an instant later I heard a sharp

creaking which could only come from the hinges of the front door. I sat up in bed and

rapped my knuckles against the rail to make certain that I was truly awake. Then I took my

watch from under the pillow. It was three in the morning. What on this earth could my wife

be doing out on the country road at three in the morning? “I am usually an extremely sound sleeper. It has been a

standing jest in the family that nothing could ever wake me during the night. And yet

somehow on that particular night, whether it may have been the slight excitement produced

by my little adventure or not I know not, but I slept much more lightly than usual. Half

in my dreams I was dimly conscious that something was going on in the room, and gradually

became aware that my wife had dressed herself and was slipping on her mantle and her

bonnet. My lips were parted to murmur out some sleepy words of surprise or remonstrance at

this untimely preparation, when suddenly my half-opened eyes fell upon her face,

illuminated by the candle-light, and astonishment held me dumb. She wore an expression

such as I had never seen before–such as I should have thought her incapable of

assuming. She was deadly pale and breathing fast, glancing furtively towards the bed as

she fastened her mantle to see if she had disturbed me. Then, thinking that I was still

asleep, she slipped noiselessly from the room, and an instant later I heard a sharp

creaking which could only come from the hinges of the front door. I sat up in bed and

rapped my knuckles against the rail to make certain that I was truly awake. Then I took my

watch from under the pillow. It was three in the morning. What on this earth could my wife

be doing out on the country road at three in the morning?

“I had sat for about twenty minutes turning the thing

over in my mind and trying to find some possible explanation. The more I thought, the more

extraordinary and inexplicable did it appear. I was still puzzling over it when I heard

the door gently close again, and her footsteps coming up the stairs. “I had sat for about twenty minutes turning the thing

over in my mind and trying to find some possible explanation. The more I thought, the more

extraordinary and inexplicable did it appear. I was still puzzling over it when I heard

the door gently close again, and her footsteps coming up the stairs.

“ ‘Where in the world have you been, Effie?’ I

asked as she entered. “ ‘Where in the world have you been, Effie?’ I

asked as she entered.

“She gave a violent start and a kind of gasping cry when

I spoke, and that cry and start troubled me more than all the rest, for there was

something indescribably guilty about them. My wife had always been a woman of a frank,

open nature, and it gave me a chill to see her slinking into her own room and crying out

and wincing when her own husband spoke to her. “She gave a violent start and a kind of gasping cry when

I spoke, and that cry and start troubled me more than all the rest, for there was

something indescribably guilty about them. My wife had always been a woman of a frank,

open nature, and it gave me a chill to see her slinking into her own room and crying out

and wincing when her own husband spoke to her.

“ ‘You awake, Jack!’ she cried with a nervous

laugh. ‘Why, I thought that nothing could awake you.’ “ ‘You awake, Jack!’ she cried with a nervous

laugh. ‘Why, I thought that nothing could awake you.’

“ ‘Where have you been?’ I asked, more sternly. “ ‘Where have you been?’ I asked, more sternly.

“ ‘I don’t wonder that you are surprised,’

said she, and I could see that her [356] fingers

were trembling as she undid the fastenings of her mantle. ‘Why, I never remember

having done such a thing in my life before. The fact is that I felt as though I were

choking and had a perfect longing for a breath of fresh air. I really think that I should

have fainted if I had not gone out. I stood at the door for a few minutes, and now I am

quite myself again.’ “ ‘I don’t wonder that you are surprised,’

said she, and I could see that her [356] fingers

were trembling as she undid the fastenings of her mantle. ‘Why, I never remember

having done such a thing in my life before. The fact is that I felt as though I were

choking and had a perfect longing for a breath of fresh air. I really think that I should

have fainted if I had not gone out. I stood at the door for a few minutes, and now I am

quite myself again.’

“All the time that she was telling me this story she

never once looked in my direction, and her voice was quite unlike her usual tones. It was

evident to me that she was saying what was false. I said nothing in reply, but turned my

face to the wall, sick at heart, with my mind filled with a thousand venomous doubts and

suspicions. What was it that my wife was concealing from me? Where had she been during

that strange expedition? I felt that I should have no peace until I knew, and yet I shrank

from asking her again after once she had told me what was false. All the rest of the night

I tossed and tumbled, framing theory after theory, each more unlikely than the last. “All the time that she was telling me this story she

never once looked in my direction, and her voice was quite unlike her usual tones. It was

evident to me that she was saying what was false. I said nothing in reply, but turned my

face to the wall, sick at heart, with my mind filled with a thousand venomous doubts and

suspicions. What was it that my wife was concealing from me? Where had she been during

that strange expedition? I felt that I should have no peace until I knew, and yet I shrank

from asking her again after once she had told me what was false. All the rest of the night

I tossed and tumbled, framing theory after theory, each more unlikely than the last.

“I should have gone to the City that day, but I was too

disturbed in my mind to be able to pay attention to business matters. My wife seemed to be

as upset as myself, and I could see from the little questioning glances which she kept

shooting at me that she understood that I disbelieved her statement, and that she was at

her wit’s end what to do. We hardly exchanged a word during breakfast, and

immediately afterwards I went out for a walk that I might think the matter out in the

fresh morning air. “I should have gone to the City that day, but I was too

disturbed in my mind to be able to pay attention to business matters. My wife seemed to be

as upset as myself, and I could see from the little questioning glances which she kept

shooting at me that she understood that I disbelieved her statement, and that she was at

her wit’s end what to do. We hardly exchanged a word during breakfast, and

immediately afterwards I went out for a walk that I might think the matter out in the

fresh morning air.

“I went as far as the Crystal Palace, spent an hour in

the grounds, and was back in Norbury by one o’clock. It happened that my way took me

past the cottage, and I stopped for an instant to look at the windows and to see if I

could catch a glimpse of the strange face which had looked out at me on the day before. As

I stood there, imagine my surprise, Mr. Holmes, when the door suddenly opened and my wife

walked out. “I went as far as the Crystal Palace, spent an hour in

the grounds, and was back in Norbury by one o’clock. It happened that my way took me

past the cottage, and I stopped for an instant to look at the windows and to see if I

could catch a glimpse of the strange face which had looked out at me on the day before. As

I stood there, imagine my surprise, Mr. Holmes, when the door suddenly opened and my wife

walked out.

“I was struck dumb with astonishment at the sight of her,

but my emotions were nothing to those which showed themselves upon her face when our eyes

met. She seemed for an instant to wish to shrink back inside the house again; and then,

seeing how useless all concealment must be, she came forward, with a very white face and

frightened eyes which belied the smile upon her lips. “I was struck dumb with astonishment at the sight of her,

but my emotions were nothing to those which showed themselves upon her face when our eyes

met. She seemed for an instant to wish to shrink back inside the house again; and then,

seeing how useless all concealment must be, she came forward, with a very white face and

frightened eyes which belied the smile upon her lips.

“ ‘Ah, Jack,’ she said, ‘I have just been

in to see if I can be of any assistance to our new neighbours. Why do you look at me like

that, Jack? You are not angry with me?’ “ ‘Ah, Jack,’ she said, ‘I have just been

in to see if I can be of any assistance to our new neighbours. Why do you look at me like

that, Jack? You are not angry with me?’

“ ‘So,’ said I, ‘this is where you went

during the night.’ “ ‘So,’ said I, ‘this is where you went

during the night.’

“ ‘What do you mean?’ she cried. “ ‘What do you mean?’ she cried.

“ ‘You came here. I am sure of it. Who are these

people that you should visit them at such an hour?’ “ ‘You came here. I am sure of it. Who are these

people that you should visit them at such an hour?’

“ ‘I have not been here before.’ “ ‘I have not been here before.’

“ ‘How can you tell me what you know is false?’

I cried. ‘Your very voice changes as you speak. When have I ever had a secret from

you? I shall enter that cottage, and I shall probe the matter to the bottom.’ “ ‘How can you tell me what you know is false?’

I cried. ‘Your very voice changes as you speak. When have I ever had a secret from

you? I shall enter that cottage, and I shall probe the matter to the bottom.’

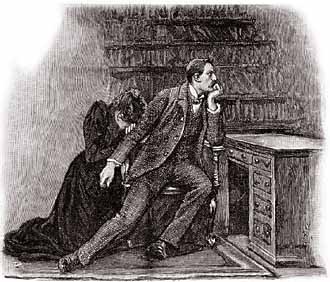

“ ‘No, no, Jack, for God’s sake!’ she

gasped in uncontrollable emotion. Then, as I approached the door, she seized my sleeve and

pulled me back with convulsive strength. “ ‘No, no, Jack, for God’s sake!’ she

gasped in uncontrollable emotion. Then, as I approached the door, she seized my sleeve and

pulled me back with convulsive strength.

“ ‘I implore you not to do this, Jack,’ she

cried. ‘I swear that I will tell you everything some day, but nothing but misery can

come of it if you enter that cottage.’ Then, as I tried to shake her off, she clung

to me in a frenzy of entreaty. “ ‘I implore you not to do this, Jack,’ she

cried. ‘I swear that I will tell you everything some day, but nothing but misery can

come of it if you enter that cottage.’ Then, as I tried to shake her off, she clung

to me in a frenzy of entreaty.

[357] “

‘Trust me, Jack!’ she cried. ‘Trust me only this once. You will never have

cause to regret it. You know that I would not have a secret from you if it were not for

your own sake. Our whole lives are at stake in this. If you come home with me all will be

well. If you force your way into that cottage all is over between us.’ [357] “

‘Trust me, Jack!’ she cried. ‘Trust me only this once. You will never have

cause to regret it. You know that I would not have a secret from you if it were not for

your own sake. Our whole lives are at stake in this. If you come home with me all will be

well. If you force your way into that cottage all is over between us.’

“There was such earnestness, such despair, in her manner

that her words arrested me, and I stood irresolute before the door. “There was such earnestness, such despair, in her manner

that her words arrested me, and I stood irresolute before the door.

“ ‘I will trust you on one condition, and on one

condition only,’ said I at last. ‘It is that this mystery comes to an end from

now. You are at liberty to preserve your secret, but you must promise me that there shall

be no more nightly visits, no more doings which are kept from my knowledge. I am willing

to forget those which are past if you will promise that there shall be no more in the

future.’ “ ‘I will trust you on one condition, and on one

condition only,’ said I at last. ‘It is that this mystery comes to an end from

now. You are at liberty to preserve your secret, but you must promise me that there shall

be no more nightly visits, no more doings which are kept from my knowledge. I am willing

to forget those which are past if you will promise that there shall be no more in the

future.’

“ ‘I was sure that you would trust me,’ she

cried with a great sigh of relief. ‘It shall be just as you wish. Come away–oh,

come away up to the house.’ “ ‘I was sure that you would trust me,’ she

cried with a great sigh of relief. ‘It shall be just as you wish. Come away–oh,

come away up to the house.’

“Still pulling at my sleeve, she led me away from the

cottage. As we went I glanced back, and there was that yellow livid face watching us out

of the upper window. What link could there be between that creature and my wife? Or how

could the coarse, rough woman whom I had seen the day before be connected with her? It was

a strange puzzle, and yet I knew that my mind could never know ease again until I had

solved it. “Still pulling at my sleeve, she led me away from the

cottage. As we went I glanced back, and there was that yellow livid face watching us out

of the upper window. What link could there be between that creature and my wife? Or how

could the coarse, rough woman whom I had seen the day before be connected with her? It was

a strange puzzle, and yet I knew that my mind could never know ease again until I had

solved it.

“For two days after this I stayed at home, and my wife

appeared to abide loyally by our engagement, for, as far as I know, she never stirred out

of the house. On the third day, however, I had ample evidence that her solemn promise was

not enough to hold her back from this secret influence which drew her away from her

husband and her duty. “For two days after this I stayed at home, and my wife

appeared to abide loyally by our engagement, for, as far as I know, she never stirred out

of the house. On the third day, however, I had ample evidence that her solemn promise was

not enough to hold her back from this secret influence which drew her away from her

husband and her duty.

“I had gone into town on that day, but I returned by the

2:40 instead of the 3:36, which is my usual train. As I entered the house the maid ran

into the hall with a startled face. “I had gone into town on that day, but I returned by the

2:40 instead of the 3:36, which is my usual train. As I entered the house the maid ran

into the hall with a startled face.

“ ‘Where is your mistress?’ I asked. “ ‘Where is your mistress?’ I asked.

“ ‘I think that she has gone out for a walk,’

she answered. “ ‘I think that she has gone out for a walk,’

she answered.

“My mind was instantly filled with suspicion. I rushed

upstairs to make sure that she was not in the house. As I did so I happened to glance out

of one of the upper windows and saw the maid with whom I had just been speaking running

across the field in the direction of the cottage. Then of course I saw exactly what it all

meant. My wife had gone over there and had asked the servant to call her if I should

return. Tingling with anger, I rushed down and hurried across, determined to end the

matter once and forever. I saw my wife and the maid hurrying back along the lane, but I

did not stop to speak with them. In the cottage lay the secret which was casting a shadow

over my life. I vowed that, come what might, it should be a secret no longer. I did not

even knock when I reached it, but turned the handle and rushed into the passage. “My mind was instantly filled with suspicion. I rushed

upstairs to make sure that she was not in the house. As I did so I happened to glance out

of one of the upper windows and saw the maid with whom I had just been speaking running

across the field in the direction of the cottage. Then of course I saw exactly what it all

meant. My wife had gone over there and had asked the servant to call her if I should

return. Tingling with anger, I rushed down and hurried across, determined to end the

matter once and forever. I saw my wife and the maid hurrying back along the lane, but I

did not stop to speak with them. In the cottage lay the secret which was casting a shadow

over my life. I vowed that, come what might, it should be a secret no longer. I did not

even knock when I reached it, but turned the handle and rushed into the passage.

“It was all still and quiet upon the ground floor. In the

kitchen a kettle was singing on the fire, and a large black cat lay coiled up in the

basket; but there was no sign of the woman whom I had seen before. I ran into the other

room, but it was equally deserted. Then I rushed up the stairs only to find two other

rooms empty and deserted at the top. There was no one at all in the whole house. The

furniture and pictures were of the most common and vulgar description, save in the one

chamber at the window of which I had seen the strange face. That was comfortable and

elegant, and all my suspicions rose into a fierce, bitter flame [358] when I saw that on the mantelpiece stood a copy of a

full-length photograph of my wife, which had been taken at my request only three months

ago. “It was all still and quiet upon the ground floor. In the

kitchen a kettle was singing on the fire, and a large black cat lay coiled up in the

basket; but there was no sign of the woman whom I had seen before. I ran into the other

room, but it was equally deserted. Then I rushed up the stairs only to find two other

rooms empty and deserted at the top. There was no one at all in the whole house. The

furniture and pictures were of the most common and vulgar description, save in the one

chamber at the window of which I had seen the strange face. That was comfortable and

elegant, and all my suspicions rose into a fierce, bitter flame [358] when I saw that on the mantelpiece stood a copy of a

full-length photograph of my wife, which had been taken at my request only three months

ago.

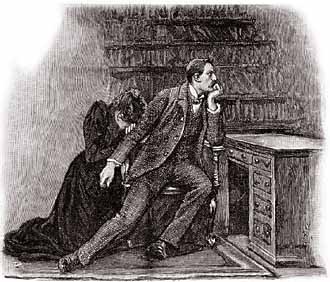

“I stayed long enough to make certain that the house was

absolutely empty. Then I left it, feeling a weight at my heart such as I had never had

before. My wife came out into the hall as I entered my house; but I was too hurt and angry

to speak with her, and, pushing past her, I made my way into my study. She followed me,

however, before I could close the door. “I stayed long enough to make certain that the house was

absolutely empty. Then I left it, feeling a weight at my heart such as I had never had

before. My wife came out into the hall as I entered my house; but I was too hurt and angry

to speak with her, and, pushing past her, I made my way into my study. She followed me,

however, before I could close the door.

“ ‘I am sorry that I broke my promise, Jack,’

said she, ‘but if you knew all the circumstances I am sure that you would forgive

me.’ “ ‘I am sorry that I broke my promise, Jack,’

said she, ‘but if you knew all the circumstances I am sure that you would forgive

me.’

“ ‘Tell me everything, then,’ said I. “ ‘Tell me everything, then,’ said I.

“ ‘I cannot, Jack, I cannot,’ she cried. “ ‘I cannot, Jack, I cannot,’ she cried.

“ ‘Until you tell me who it is that has been living

in that cottage, and who it is to whom you have given that photograph, there can never be

any confidence between us,’ said I, and breaking away from her I left the house. That

was yesterday, Mr. Holmes, and I have not seen her since, nor do I know anything more

about this strange business. It is the first shadow that has come between us, and it has

so shaken me that I do not know what I should do for the best. Suddenly this morning it

occurred to me that you were the man to advise me, so I have hurried to you now, and I

place myself unreservedly in your hands. If there is any point which I have not made

clear, pray question me about it. But, above all, tell me quickly what I am to do, for

this misery is more than I can bear.” “ ‘Until you tell me who it is that has been living

in that cottage, and who it is to whom you have given that photograph, there can never be

any confidence between us,’ said I, and breaking away from her I left the house. That

was yesterday, Mr. Holmes, and I have not seen her since, nor do I know anything more

about this strange business. It is the first shadow that has come between us, and it has

so shaken me that I do not know what I should do for the best. Suddenly this morning it

occurred to me that you were the man to advise me, so I have hurried to you now, and I

place myself unreservedly in your hands. If there is any point which I have not made

clear, pray question me about it. But, above all, tell me quickly what I am to do, for

this misery is more than I can bear.”

Holmes and I had listened with the utmost interest to this

extraordinary statement, which had been delivered in the jerky, broken fashion of a man

who is under the influence of extreme emotion. My companion sat silent now for some time,

with his chin upon his hand, lost in thought. Holmes and I had listened with the utmost interest to this

extraordinary statement, which had been delivered in the jerky, broken fashion of a man

who is under the influence of extreme emotion. My companion sat silent now for some time,

with his chin upon his hand, lost in thought.

“Tell me,” said he at last, “could you swear

that this was a man’s face which you saw at the window?” “Tell me,” said he at last, “could you swear

that this was a man’s face which you saw at the window?”

“Each time that I saw it I was some distance away from

it, so that it is impossible for me to say.” “Each time that I saw it I was some distance away from

it, so that it is impossible for me to say.”

“You appear, however, to have been disagreeably impressed

by it.” “You appear, however, to have been disagreeably impressed

by it.”

“It seemed to be of an unusual colour and to have a

strange rigidity about the features. When I approached it vanished with a jerk.” “It seemed to be of an unusual colour and to have a

strange rigidity about the features. When I approached it vanished with a jerk.”

“How long is it since your wife asked you for a hundred

pounds?” “How long is it since your wife asked you for a hundred

pounds?”

“Nearly two months.” “Nearly two months.”

“Have you ever seen a photograph of her first

husband?” “Have you ever seen a photograph of her first

husband?”

“No, there was a great fire at Atlanta very shortly after

his death, and all her papers were destroyed.” “No, there was a great fire at Atlanta very shortly after

his death, and all her papers were destroyed.”

“And yet she had a certificate of death. You say that you

saw it.” “And yet she had a certificate of death. You say that you

saw it.”

“Yes, she got a duplicate after the fire.” “Yes, she got a duplicate after the fire.”

“Did you ever meet anyone who knew her in America?” “Did you ever meet anyone who knew her in America?”

“No.” “No.”

“Did she ever talk of revisiting the place?” “Did she ever talk of revisiting the place?”

“No.” “No.”

“Or get letters from it?” “Or get letters from it?”

“No.” “No.”

“Thank you. I should like to think over the matter a

little now. If the cottage is now permanently deserted we may have some difficulty. If, on

the other hand, as I fancy is more likely, the inmates were warned of your coming and left

before you entered yesterday, then they may be back now, and we should clear it all up [359] easily. Let me advise you,

then, to return to Norbury and to examine the windows of the cottage again. If you have

reason to believe that it is inhabited, do not force your way in, but send a wire to my

friend and me. We shall be with you within an hour of receiving it, and we shall then very

soon get to the bottom of the business.” “Thank you. I should like to think over the matter a

little now. If the cottage is now permanently deserted we may have some difficulty. If, on

the other hand, as I fancy is more likely, the inmates were warned of your coming and left

before you entered yesterday, then they may be back now, and we should clear it all up [359] easily. Let me advise you,

then, to return to Norbury and to examine the windows of the cottage again. If you have

reason to believe that it is inhabited, do not force your way in, but send a wire to my

friend and me. We shall be with you within an hour of receiving it, and we shall then very

soon get to the bottom of the business.”

“And if it is still empty?” “And if it is still empty?”

“In that case I shall come out to-morrow and talk it over

with you. Good-bye, and, above all, do not fret until you know that you really have a

cause for it.” “In that case I shall come out to-morrow and talk it over

with you. Good-bye, and, above all, do not fret until you know that you really have a

cause for it.”

“I am afraid that this is a bad business, Watson,”

said my companion as he returned after accompanying Mr. Grant Munro to the door.

“What do you make of it?” “I am afraid that this is a bad business, Watson,”

said my companion as he returned after accompanying Mr. Grant Munro to the door.

“What do you make of it?”

“It had an ugly sound,” I answered. “It had an ugly sound,” I answered.

“Yes. There’s blackmail in it, or I am much

mistaken.” “Yes. There’s blackmail in it, or I am much

mistaken.”

“And who is the blackmailer?” “And who is the blackmailer?”

“Well, it must be the creature who lives in the only

comfortable room in the place and has her photograph above his fireplace. Upon my word,

Watson, there is something very attractive about that livid face at the window, and I

would not have missed the case for worlds.” “Well, it must be the creature who lives in the only

comfortable room in the place and has her photograph above his fireplace. Upon my word,

Watson, there is something very attractive about that livid face at the window, and I

would not have missed the case for worlds.”

“You have a theory?” “You have a theory?”

“Yes, a provisional one. But I shall be surprised if it

does not turn out to be correct. This woman’s first husband is in that cottage.” “Yes, a provisional one. But I shall be surprised if it

does not turn out to be correct. This woman’s first husband is in that cottage.”

“Why do you think so?” “Why do you think so?”

“How else can we explain her frenzied anxiety that her

second one should not enter it? The facts, as I read them, are something like this: This

woman was married in America. Her husband developed some hateful qualities, or shall we

say he contracted some loathsome disease and became a leper or an imbecile? She flies from

him at last, returns to England, changes her name, and starts her life, as she thinks,

afresh. She has been married three years and believes that her position is quite secure,

having shown her husband the death certificate of some man whose name she has assumed,

when suddenly her whereabouts is discovered by her first husband, or, we may suppose, by

some unscrupulous woman who has attached herself to the invalid. They write to the wife

and threaten to come and expose her. She asks for a hundred pounds and endeavours to buy

them off. They come in spite of it, and when the husband mentions casually to the wife

that there are newcomers in the cottage, she knows in some way that they are her pursuers.

She waits until her husband is asleep, and then she rushes down to endeavour to persuade

them to leave her in peace. Having no success, she goes again next morning, and her

husband meets her, as he has told us, as she comes out. She promises him then not to go

there again, but two days afterwards the hope of getting rid of those dreadful neighbours

was too strong for her, and she made another attempt, taking down with her the photograph

which had probably been demanded from her. In the midst of this interview the maid rushed

in to say that the master had come home, on which the wife, knowing that he would come

straight down to the cottage, hurried the inmates out at the back door, into the grove of

fir-trees, probably, which was mentioned as standing near. In this way he found the place

deserted. I shall be very much surprised, however, if it is still so when he reconnoitres

it this evening. What do you think of my theory?” “How else can we explain her frenzied anxiety that her

second one should not enter it? The facts, as I read them, are something like this: This

woman was married in America. Her husband developed some hateful qualities, or shall we

say he contracted some loathsome disease and became a leper or an imbecile? She flies from

him at last, returns to England, changes her name, and starts her life, as she thinks,

afresh. She has been married three years and believes that her position is quite secure,

having shown her husband the death certificate of some man whose name she has assumed,

when suddenly her whereabouts is discovered by her first husband, or, we may suppose, by

some unscrupulous woman who has attached herself to the invalid. They write to the wife

and threaten to come and expose her. She asks for a hundred pounds and endeavours to buy

them off. They come in spite of it, and when the husband mentions casually to the wife

that there are newcomers in the cottage, she knows in some way that they are her pursuers.

She waits until her husband is asleep, and then she rushes down to endeavour to persuade

them to leave her in peace. Having no success, she goes again next morning, and her

husband meets her, as he has told us, as she comes out. She promises him then not to go

there again, but two days afterwards the hope of getting rid of those dreadful neighbours

was too strong for her, and she made another attempt, taking down with her the photograph

which had probably been demanded from her. In the midst of this interview the maid rushed

in to say that the master had come home, on which the wife, knowing that he would come

straight down to the cottage, hurried the inmates out at the back door, into the grove of

fir-trees, probably, which was mentioned as standing near. In this way he found the place

deserted. I shall be very much surprised, however, if it is still so when he reconnoitres

it this evening. What do you think of my theory?”

“It is all surmise.” “It is all surmise.”

“But at least it covers all the facts. When new facts

come to our knowledge [360] which

cannot be covered by it, it will be time enough to reconsider it. We can do nothing more

until we have a message from our friend at Norbury.” “But at least it covers all the facts. When new facts

come to our knowledge [360] which

cannot be covered by it, it will be time enough to reconsider it. We can do nothing more

until we have a message from our friend at Norbury.”

But we had not a very long time to wait for that. It came just

as we had finished our tea. But we had not a very long time to wait for that. It came just

as we had finished our tea.

The cottage is still tenanted [it said]. Have seen the face

again at the window. Will meet the seven-o’clock train and will take no steps until

you arrive. The cottage is still tenanted [it said]. Have seen the face

again at the window. Will meet the seven-o’clock train and will take no steps until

you arrive.

He was waiting on the platform when we stepped out, and we

could see in the light of the station lamps that he was very pale, and quivering with

agitation. He was waiting on the platform when we stepped out, and we

could see in the light of the station lamps that he was very pale, and quivering with

agitation.

“They are still there, Mr. Holmes,” said he, laying

his hand hard upon my friend’s sleeve. “I saw lights in the cottage as I came

down. We shall settle it now once and for all.” “They are still there, Mr. Holmes,” said he, laying

his hand hard upon my friend’s sleeve. “I saw lights in the cottage as I came

down. We shall settle it now once and for all.”

“What is your plan, then?” asked Holmes as he walked

down the dark tree-lined road. “What is your plan, then?” asked Holmes as he walked

down the dark tree-lined road.

“I am going to force my way in and see for myself who is

in the house. I wish you both to be there as witnesses.” “I am going to force my way in and see for myself who is

in the house. I wish you both to be there as witnesses.”

“You are quite determined to do this in spite of your

wife’s warning that it is better that you should not solve the mystery?” “You are quite determined to do this in spite of your

wife’s warning that it is better that you should not solve the mystery?”

“Yes, I am determined.” “Yes, I am determined.”

“Well, I think that you are in the right. Any truth is

better than indefinite doubt. We had better go up at once. Of course, legally, we are

putting ourselves hopelessly in the wrong; but I think that it is worth it.” “Well, I think that you are in the right. Any truth is

better than indefinite doubt. We had better go up at once. Of course, legally, we are

putting ourselves hopelessly in the wrong; but I think that it is worth it.”

It was a very dark night, and a thin rain began to fall as we

turned from the highroad into a narrow lane, deeply rutted, with hedges on either side.

Mr. Grant Munro pushed impatiently forward, however, and we stumbled after him as best we

could. It was a very dark night, and a thin rain began to fall as we

turned from the highroad into a narrow lane, deeply rutted, with hedges on either side.

Mr. Grant Munro pushed impatiently forward, however, and we stumbled after him as best we

could.

“There are the lights of my house,” he murmured,

pointing to a glimmer among the trees. “And here is the cottage which I am going to

enter.” “There are the lights of my house,” he murmured,

pointing to a glimmer among the trees. “And here is the cottage which I am going to

enter.”

We turned a corner in the lane as he spoke, and there was the

building close beside us. A yellow bar falling across the black foreground showed that the

door was not quite closed, and one window in the upper story was brightly illuminated. As

we looked, we saw a dark blur moving across the blind. We turned a corner in the lane as he spoke, and there was the

building close beside us. A yellow bar falling across the black foreground showed that the

door was not quite closed, and one window in the upper story was brightly illuminated. As

we looked, we saw a dark blur moving across the blind.

“There is that creature!” cried Grant Munro.

“You can see for yourselves that someone is there. Now follow me, and we shall soon

know all.” “There is that creature!” cried Grant Munro.

“You can see for yourselves that someone is there. Now follow me, and we shall soon

know all.”

We approached the door, but suddenly a woman appeared out of

the shadow and stood in the golden track of the lamplight. I could not see her face in the

darkness, but her arms were thrown out in an attitude of entreaty. We approached the door, but suddenly a woman appeared out of

the shadow and stood in the golden track of the lamplight. I could not see her face in the

darkness, but her arms were thrown out in an attitude of entreaty.

“For God’s sake, don’t, Jack!” she cried.

“I had a presentiment that you would come this evening. Think better of it, dear!

Trust me again, and you will never have cause to regret it.” “For God’s sake, don’t, Jack!” she cried.

“I had a presentiment that you would come this evening. Think better of it, dear!

Trust me again, and you will never have cause to regret it.”

“I have trusted you too long, Effie,” he cried

sternly. “Leave go of me! I must pass you. My friends and I are going to settle this

matter once and forever!” He pushed her to one side, and we followed closely after

him. As he threw the door open an old woman ran out in front of him and tried to bar his

passage, but he thrust her back, and an instant afterwards we were all upon the stairs.

Grant Munro rushed into the lighted room at the top, and we entered at his heels. “I have trusted you too long, Effie,” he cried

sternly. “Leave go of me! I must pass you. My friends and I are going to settle this

matter once and forever!” He pushed her to one side, and we followed closely after

him. As he threw the door open an old woman ran out in front of him and tried to bar his

passage, but he thrust her back, and an instant afterwards we were all upon the stairs.

Grant Munro rushed into the lighted room at the top, and we entered at his heels.

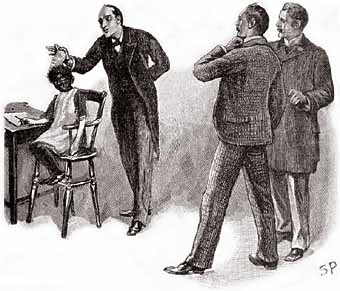

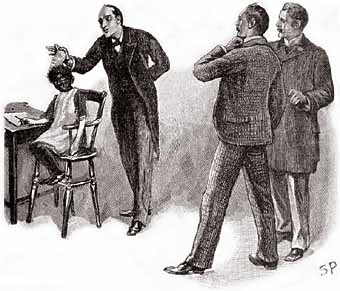

It was a cosy, well-furnished apartment, with two candles

burning upon the table and two upon the mantelpiece. In the corner, stooping over a desk,

there sat [361] what

appeared to be a little girl. Her face was turned away as we entered, but we could see

that she was dressed in a red frock, and that she had long white gloves on. As she whisked

round to us, I gave a cry of surprise and horror. The face which she turned towards us was

of the strangest livid tint, and the features were absolutely devoid of any expression. An

instant later the mystery was explained. Holmes, with a laugh, passed his hand behind the

child’s ear, a mask peeled off from her countenance, and there was a little

coal-black negress, with all her white teeth flashing in amusement at our amazed faces. I

burst out laughing, out of sympathy with her merriment; but Grant Munro stood staring,

with his hand clutching his throat. It was a cosy, well-furnished apartment, with two candles

burning upon the table and two upon the mantelpiece. In the corner, stooping over a desk,

there sat [361] what

appeared to be a little girl. Her face was turned away as we entered, but we could see

that she was dressed in a red frock, and that she had long white gloves on. As she whisked

round to us, I gave a cry of surprise and horror. The face which she turned towards us was

of the strangest livid tint, and the features were absolutely devoid of any expression. An

instant later the mystery was explained. Holmes, with a laugh, passed his hand behind the

child’s ear, a mask peeled off from her countenance, and there was a little

coal-black negress, with all her white teeth flashing in amusement at our amazed faces. I

burst out laughing, out of sympathy with her merriment; but Grant Munro stood staring,

with his hand clutching his throat.

“My God!” he cried. “What can be the meaning

of this?” “My God!” he cried. “What can be the meaning

of this?”

“I will tell you the meaning of it,” cried the lady,

sweeping into the room with a proud, set face. “You have forced me, against my own

judgment, to tell you, and now we must both make the best of it. My husband died at

Atlanta. My child survived.” “I will tell you the meaning of it,” cried the lady,

sweeping into the room with a proud, set face. “You have forced me, against my own

judgment, to tell you, and now we must both make the best of it. My husband died at

Atlanta. My child survived.”

“Your child?” “Your child?”

She drew a large silver locket from her bosom. “You have

never seen this open.” She drew a large silver locket from her bosom. “You have

never seen this open.”

“I understood that it did not open.” “I understood that it did not open.”

She touched a spring, and the front hinged back. There was a

portrait within of a man strikingly handsome and intelligent-looking, but bearing

unmistakable signs upon his features of his African descent. She touched a spring, and the front hinged back. There was a

portrait within of a man strikingly handsome and intelligent-looking, but bearing

unmistakable signs upon his features of his African descent.

“That is John Hebron, of Atlanta,” said the lady,

“and a nobler man never walked the earth. I cut myself off from my race in order to

wed him, but never once while he lived did I for an instant regret it. It was our

misfortune that our only child took after his people rather than mine. It is often so in

such matches, and little Lucy is darker far than ever her father was. But dark or fair,

she is my own dear little girlie, and her mother’s pet.” The little creature ran

across at the words and nestled up against the lady’s dress. “When I left her in

America,” she continued, “it was only because her health was weak, and the

change might have done her harm. She was given to the care of a faithful Scotch woman who

had once been our servant. Never for an instant did I dream of disowning her as my child.

But when chance threw you in my way, Jack, and I learned to love you, I feared to tell you

about my child. God forgive me, I feared that I should lose you, and I had not the courage

to tell you. I had to choose between you, and in my weakness I turned away from my own

little girl. For three years I have kept her existence a secret from you, but I heard from

the nurse, and I knew that all was well with her. At last, however, there came an

overwhelming desire to see the child once more. I struggled against it, but in vain.

Though I knew the danger, I determined to have the child over, if it were but for a few

weeks. I sent a hundred pounds to the nurse, and I gave her instructions about this

cottage, so that she might come as a neighbour, without my appearing to be in any way

connected with her. I pushed my precautions so far as to order her to keep the child in

the house during the daytime, and to cover up her little face and hands so that even those

who might see her at the window should not gossip about there being a black child in the

neighbourhood. If I had been less cautious I might have been more wise, but I was half

crazy with fear that you should learn the truth. “That is John Hebron, of Atlanta,” said the lady,

“and a nobler man never walked the earth. I cut myself off from my race in order to

wed him, but never once while he lived did I for an instant regret it. It was our

misfortune that our only child took after his people rather than mine. It is often so in

such matches, and little Lucy is darker far than ever her father was. But dark or fair,

she is my own dear little girlie, and her mother’s pet.” The little creature ran

across at the words and nestled up against the lady’s dress. “When I left her in

America,” she continued, “it was only because her health was weak, and the

change might have done her harm. She was given to the care of a faithful Scotch woman who

had once been our servant. Never for an instant did I dream of disowning her as my child.

But when chance threw you in my way, Jack, and I learned to love you, I feared to tell you

about my child. God forgive me, I feared that I should lose you, and I had not the courage

to tell you. I had to choose between you, and in my weakness I turned away from my own

little girl. For three years I have kept her existence a secret from you, but I heard from

the nurse, and I knew that all was well with her. At last, however, there came an

overwhelming desire to see the child once more. I struggled against it, but in vain.

Though I knew the danger, I determined to have the child over, if it were but for a few

weeks. I sent a hundred pounds to the nurse, and I gave her instructions about this

cottage, so that she might come as a neighbour, without my appearing to be in any way

connected with her. I pushed my precautions so far as to order her to keep the child in

the house during the daytime, and to cover up her little face and hands so that even those

who might see her at the window should not gossip about there being a black child in the

neighbourhood. If I had been less cautious I might have been more wise, but I was half

crazy with fear that you should learn the truth.

“It was you who told me first that the cottage was

occupied. I should have waited for the morning, but I could not sleep for excitement, and

so at last I slipped out, knowing how difficult it is to awake you. But you saw me go, and

that was [362] the beginning

of my troubles. Next day you had my secret at your mercy, but you nobly refrained from

pursuing your advantage. Three days later, however, the nurse and child only just escaped

from the back door as you rushed in at the front one. And now to-night you at last know

all, and I ask you what is to become of us, my child and me?” She clasped her hands

and waited for an answer. “It was you who told me first that the cottage was

occupied. I should have waited for the morning, but I could not sleep for excitement, and

so at last I slipped out, knowing how difficult it is to awake you. But you saw me go, and

that was [362] the beginning

of my troubles. Next day you had my secret at your mercy, but you nobly refrained from

pursuing your advantage. Three days later, however, the nurse and child only just escaped

from the back door as you rushed in at the front one. And now to-night you at last know

all, and I ask you what is to become of us, my child and me?” She clasped her hands

and waited for an answer.

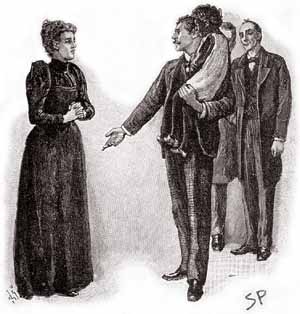

It was a long ten minutes before Grant Munro broke the

silence, and when his answer came it was one of which I love to think. He lifted the

little child, kissed her, and then, still carrying her, he held his other hand out to his

wife and turned towards the door. It was a long ten minutes before Grant Munro broke the

silence, and when his answer came it was one of which I love to think. He lifted the

little child, kissed her, and then, still carrying her, he held his other hand out to his

wife and turned towards the door.

“We can talk it over more comfortably at home,”

said he. “I am not a very good man, Effie, but I think that I am a better one than

you have given me credit for being.” “We can talk it over more comfortably at home,”

said he. “I am not a very good man, Effie, but I think that I am a better one than

you have given me credit for being.”

Holmes and I followed them down the lane, and my friend

plucked at my sleeve as we came out. Holmes and I followed them down the lane, and my friend

plucked at my sleeve as we came out.

“I think,” said he, “that we shall be of more

use in London than in Norbury.” “I think,” said he, “that we shall be of more

use in London than in Norbury.”

Not another word did he say of the case until late that night,

when he was turning away, with his lighted candle, for his bedroom. Not another word did he say of the case until late that night,

when he was turning away, with his lighted candle, for his bedroom.

“Watson,” said he, “if it should ever strike

you that I am getting a little over-confident in my powers, or giving less pains to a case

than it deserves, kindly whisper ‘Norbury’ in my ear, and I shall be infinitely

obliged to you.” “Watson,” said he, “if it should ever strike

you that I am getting a little over-confident in my powers, or giving less pains to a case

than it deserves, kindly whisper ‘Norbury’ in my ear, and I shall be infinitely

obliged to you.”

|

[In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous

cases in which my companion’s singular gifts have made us the listeners to, and

eventually the actors in, some strange drama, it is only natural that I should dwell

rather upon his successes than upon his failures. And this not so much for the sake of his

reputation–for, indeed, it was when he was at his wit’s end that his energy and

his versatility were most admirable–but because [351] where he failed it happened too often that no one else

succeeded, and that the tale was left forever without a conclusion. Now and again,

however, it chanced that even when he erred the truth was still discovered. I have noted

of some half-dozen cases of the kind; the adventure of the Musgrave Ritual and that which

I am about to recount are the two which present the strongest features of interest.]

[In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous

cases in which my companion’s singular gifts have made us the listeners to, and

eventually the actors in, some strange drama, it is only natural that I should dwell

rather upon his successes than upon his failures. And this not so much for the sake of his

reputation–for, indeed, it was when he was at his wit’s end that his energy and

his versatility were most admirable–but because [351] where he failed it happened too often that no one else

succeeded, and that the tale was left forever without a conclusion. Now and again,

however, it chanced that even when he erred the truth was still discovered. I have noted

of some half-dozen cases of the kind; the adventure of the Musgrave Ritual and that which

I am about to recount are the two which present the strongest features of interest.]![]() One day in early spring he had so far relaxed as to go for a

walk with me in the Park, where the first faint shoots of green were breaking out upon the

elms, and the sticky spear-heads of the chestnuts were just beginning to burst into their

fivefold leaves. For two hours we rambled about together, in silence for the most part, as

befits two men who know each other intimately. It was nearly five before we were back in

Baker Street once more.

One day in early spring he had so far relaxed as to go for a

walk with me in the Park, where the first faint shoots of green were breaking out upon the

elms, and the sticky spear-heads of the chestnuts were just beginning to burst into their

fivefold leaves. For two hours we rambled about together, in silence for the most part, as

befits two men who know each other intimately. It was nearly five before we were back in

Baker Street once more.![]() “Beg pardon, sir,” said our page-boy as he opened

the door. “There’s been a gentleman here asking for you, sir.”

“Beg pardon, sir,” said our page-boy as he opened

the door. “There’s been a gentleman here asking for you, sir.”![]() Holmes glanced reproachfully at me. “So much for

afternoon walks!” said he. “Has this gentleman gone, then?”

Holmes glanced reproachfully at me. “So much for

afternoon walks!” said he. “Has this gentleman gone, then?”![]() “Yes, sir.”

“Yes, sir.”![]() “Didn’t you ask him in?”

“Didn’t you ask him in?”![]() “Yes, sir, he came in.”

“Yes, sir, he came in.”![]() “How long did he wait?”

“How long did he wait?”![]() “Half an hour, sir. He was a very restless gentleman,

sir, a-walkin’ and a-stampin’ all the time he was here. I was waitin’

outside the door, sir, and I could hear him. At last he outs into the passage, and he

cries, ‘Is that man never goin’ to come?’ Those were his very words, sir.

‘You’ll only need to wait a little longer,’ says I. ‘Then I’ll

wait in the open air, for I feel half choked,’ says he. ‘I’ll be back

before long.’ And with that he ups and he outs, and all I could say wouldn’t

hold him back.”

“Half an hour, sir. He was a very restless gentleman,

sir, a-walkin’ and a-stampin’ all the time he was here. I was waitin’

outside the door, sir, and I could hear him. At last he outs into the passage, and he

cries, ‘Is that man never goin’ to come?’ Those were his very words, sir.

‘You’ll only need to wait a little longer,’ says I. ‘Then I’ll

wait in the open air, for I feel half choked,’ says he. ‘I’ll be back

before long.’ And with that he ups and he outs, and all I could say wouldn’t