|

|

Will come without fail to-night and

bring new sparking plugs. Will come without fail to-night and

bring new sparking plugs.

- ALTAMONT.

“Sparking plugs, eh?” “Sparking plugs, eh?”

“You see he poses as a motor expert

and I keep a full garage. In our code everything likely to come up is named after some

spare part. If he talks of a radiator it is a battleship, of an oil pump a cruiser, and so

on. Sparking plugs are naval signals.” “You see he poses as a motor expert

and I keep a full garage. In our code everything likely to come up is named after some

spare part. If he talks of a radiator it is a battleship, of an oil pump a cruiser, and so

on. Sparking plugs are naval signals.”

“From Portsmouth at midday,”

said the secretary, examining the superscription. “By the way, what do you give

him?” “From Portsmouth at midday,”

said the secretary, examining the superscription. “By the way, what do you give

him?”

“Five hundred pounds for this

particular job. Of course he has a salary as well.” “Five hundred pounds for this

particular job. Of course he has a salary as well.”

“The greedy rogue. They are useful,

these traitors, but I grudge them their blood money.” “The greedy rogue. They are useful,

these traitors, but I grudge them their blood money.”

“I grudge Altamont nothing. He is a

wonderful worker. If I pay him well, at least he delivers the goods, to use his own

phrase. Besides he is not a traitor. I assure you that our most pan-Germanic Junker is a

sucking dove in his feelings towards England as compared with a real bitter

Irish-American.” “I grudge Altamont nothing. He is a

wonderful worker. If I pay him well, at least he delivers the goods, to use his own

phrase. Besides he is not a traitor. I assure you that our most pan-Germanic Junker is a

sucking dove in his feelings towards England as compared with a real bitter

Irish-American.”

“Oh, an Irish-American?” “Oh, an Irish-American?”

“If you heard him talk you would not

doubt it. Sometimes I assure you I can hardly understand him. He seems to have declared

war on the King’s English as well as on the English king. Must you really go? He may

be here any moment.” “If you heard him talk you would not

doubt it. Sometimes I assure you I can hardly understand him. He seems to have declared

war on the King’s English as well as on the English king. Must you really go? He may

be here any moment.”

“No. I’m sorry, but I have

already overstayed my time. We shall expect you early to-morrow, and when you get that

signal book through the little door on [974]

the Duke of York’s steps you can put a triumphant finis to your record

in England. What! Tokay!” He indicated a heavily sealed dust-covered bottle which

stood with two high glasses upon a salver. “No. I’m sorry, but I have

already overstayed my time. We shall expect you early to-morrow, and when you get that

signal book through the little door on [974]

the Duke of York’s steps you can put a triumphant finis to your record

in England. What! Tokay!” He indicated a heavily sealed dust-covered bottle which

stood with two high glasses upon a salver.

“May I offer you a glass before your

journey?” “May I offer you a glass before your

journey?”

“No, thanks. But it looks like

revelry.” “No, thanks. But it looks like

revelry.”

“Altamont has a nice taste in wines,

and he took a fancy to my Tokay. He is a touchy fellow and needs humouring in small

things. I have to study him, I assure you.” They had strolled out on to the terrace

again, and along it to the further end where at a touch from the Baron’s chauffeur

the great car shivered and chuckled. “Those are the lights of Harwich, I

suppose,” said the secretary, pulling on his dust coat. “How still and peaceful

it all seems. There may be other lights within the week, and the English coast a less

tranquil place! The heavens, too, may not be quite so peaceful if all that the good

Zeppelin promises us comes true. By the way, who is that?” “Altamont has a nice taste in wines,

and he took a fancy to my Tokay. He is a touchy fellow and needs humouring in small

things. I have to study him, I assure you.” They had strolled out on to the terrace

again, and along it to the further end where at a touch from the Baron’s chauffeur

the great car shivered and chuckled. “Those are the lights of Harwich, I

suppose,” said the secretary, pulling on his dust coat. “How still and peaceful

it all seems. There may be other lights within the week, and the English coast a less

tranquil place! The heavens, too, may not be quite so peaceful if all that the good

Zeppelin promises us comes true. By the way, who is that?”

Only one window showed a light behind

them; in it there stood a lamp, and beside it, seated at a table, was a dear old

ruddy-faced woman in a country cap. She was bending over her knitting and stopping

occasionally to stroke a large black cat upon a stool beside her. Only one window showed a light behind

them; in it there stood a lamp, and beside it, seated at a table, was a dear old

ruddy-faced woman in a country cap. She was bending over her knitting and stopping

occasionally to stroke a large black cat upon a stool beside her.

“That is Martha, the only servant I

have left.” “That is Martha, the only servant I

have left.”

The secretary chuckled. The secretary chuckled.

“She might almost personify

Britannia,” said he, “with her complete self-absorption and general air of

comfortable somnolence. Well, au revoir, Von Bork!” With a final wave of his

hand he sprang into the car, and a moment later the two golden cones from the headlights

shot forward through the darkness. The secretary lay back in the cushions of the luxurious

limousine, with his thoughts so full of the impending European tragedy that he hardly

observed that as his car swung round the village street it nearly passed over a little

Ford coming in the opposite direction. “She might almost personify

Britannia,” said he, “with her complete self-absorption and general air of

comfortable somnolence. Well, au revoir, Von Bork!” With a final wave of his

hand he sprang into the car, and a moment later the two golden cones from the headlights

shot forward through the darkness. The secretary lay back in the cushions of the luxurious

limousine, with his thoughts so full of the impending European tragedy that he hardly

observed that as his car swung round the village street it nearly passed over a little

Ford coming in the opposite direction.

Von Bork walked slowly back to the study

when the last gleams of the motor lamps had faded into the distance. As he passed he

observed that his old housekeeper had put out her lamp and retired. It was a new

experience to him, the silence and darkness of his widespread house, for his family and

household had been a large one. It was a relief to him, however, to think that they were

all in safety and that, but for that one old woman who had lingered in the kitchen, he had

the whole place to himself. There was a good deal of tidying up to do inside his study and

he set himself to do it until his keen, handsome face was flushed with the heat of the

burning papers. A leather valise stood beside his table, and into this he began to pack

very neatly and systematically the precious contents of his safe. He had hardly got

started with the work, however, when his quick ears caught the sound of a distant car.

Instantly he gave an exclamation of satisfaction, strapped up the valise, shut the safe,

locked it, and hurried out on to the terrace. He was just in time to see the lights of a

small car come to a halt at the gate. A passenger sprang out of it and advanced swiftly

towards him, while the chauffeur, a heavily built, elderly man with a gray moustache,

settled down like one who resigns himself to a long vigil. Von Bork walked slowly back to the study

when the last gleams of the motor lamps had faded into the distance. As he passed he

observed that his old housekeeper had put out her lamp and retired. It was a new

experience to him, the silence and darkness of his widespread house, for his family and

household had been a large one. It was a relief to him, however, to think that they were

all in safety and that, but for that one old woman who had lingered in the kitchen, he had

the whole place to himself. There was a good deal of tidying up to do inside his study and

he set himself to do it until his keen, handsome face was flushed with the heat of the

burning papers. A leather valise stood beside his table, and into this he began to pack

very neatly and systematically the precious contents of his safe. He had hardly got

started with the work, however, when his quick ears caught the sound of a distant car.

Instantly he gave an exclamation of satisfaction, strapped up the valise, shut the safe,

locked it, and hurried out on to the terrace. He was just in time to see the lights of a

small car come to a halt at the gate. A passenger sprang out of it and advanced swiftly

towards him, while the chauffeur, a heavily built, elderly man with a gray moustache,

settled down like one who resigns himself to a long vigil.

“Well?” asked Von Bork eagerly,

running forward to meet his visitor. “Well?” asked Von Bork eagerly,

running forward to meet his visitor.

For answer the man waved a small

brown-paper parcel triumphantly above his head. For answer the man waved a small

brown-paper parcel triumphantly above his head.

[975] “You can give me the glad hand to-night,

mister,” he cried. “I’m bringing home the bacon at last.” [975] “You can give me the glad hand to-night,

mister,” he cried. “I’m bringing home the bacon at last.”

“The signals?” “The signals?”

“Same as I said in my cable. Every

last one of them, semaphore, lamp code, Marconi–a copy, mind you, not the original.

That was too dangerous. But it’s the real goods, and you can lay to that.” He

slapped the German upon the shoulder with a rough familiarity from which the other winced. “Same as I said in my cable. Every

last one of them, semaphore, lamp code, Marconi–a copy, mind you, not the original.

That was too dangerous. But it’s the real goods, and you can lay to that.” He

slapped the German upon the shoulder with a rough familiarity from which the other winced.

“Come in,” he said.

“I’m all alone in the house. I was only waiting for this. Of course a copy is

better than the original. If an original were missing they would change the whole thing.

You think it’s all safe about the copy?” “Come in,” he said.

“I’m all alone in the house. I was only waiting for this. Of course a copy is

better than the original. If an original were missing they would change the whole thing.

You think it’s all safe about the copy?”

The Irish-American had entered the study

and stretched his long limbs from the armchair. He was a tall, gaunt man of sixty, with

clear-cut features and a small goatee beard which gave him a general resemblance to the

caricatures of Uncle Sam. A half-smoked, sodden cigar hung from the corner of his mouth,

and as he sat down he struck a match and relit it. “Making ready for a move?” he

remarked as he looked round him. “Say, mister,” he added, as his eyes fell upon

the safe from which the curtain was now removed, “you don’t tell me you keep

your papers in that?” The Irish-American had entered the study

and stretched his long limbs from the armchair. He was a tall, gaunt man of sixty, with

clear-cut features and a small goatee beard which gave him a general resemblance to the

caricatures of Uncle Sam. A half-smoked, sodden cigar hung from the corner of his mouth,

and as he sat down he struck a match and relit it. “Making ready for a move?” he

remarked as he looked round him. “Say, mister,” he added, as his eyes fell upon

the safe from which the curtain was now removed, “you don’t tell me you keep

your papers in that?”

“Why not?” “Why not?”

“Gosh, in a wide-open contraption

like that! And they reckon you to be some spy. Why, a Yankee crook would be into that with

a can-opener. If I’d known that any letter of mine was goin’ to lie loose in a

thing like that I’d have been a mug to write to you at all.” “Gosh, in a wide-open contraption

like that! And they reckon you to be some spy. Why, a Yankee crook would be into that with

a can-opener. If I’d known that any letter of mine was goin’ to lie loose in a

thing like that I’d have been a mug to write to you at all.”

“It would puzzle any crook to force

that safe,” Von Bork answered. “You won’t cut that metal with any

tool.” “It would puzzle any crook to force

that safe,” Von Bork answered. “You won’t cut that metal with any

tool.”

“But the lock?” “But the lock?”

“No, it’s a double combination

lock. You know what that is?” “No, it’s a double combination

lock. You know what that is?”

“Search me,” said the American. “Search me,” said the American.

“Well, you need a word as well as a

set of figures before you can get the lock to work.” He rose and showed a

double-radiating disc round the keyhole. “This outer one is for the letters, the

inner one for the figures.” “Well, you need a word as well as a

set of figures before you can get the lock to work.” He rose and showed a

double-radiating disc round the keyhole. “This outer one is for the letters, the

inner one for the figures.”

“Well, well, that’s fine.” “Well, well, that’s fine.”

“So it’s not quite as simple as

you thought. It was four years ago that I had it made, and what do you think I chose for

the word and figures?” “So it’s not quite as simple as

you thought. It was four years ago that I had it made, and what do you think I chose for

the word and figures?”

“It’s beyond me.” “It’s beyond me.”

“Well, I chose August for the word,

and 1914 for the figures, and here we are.” “Well, I chose August for the word,

and 1914 for the figures, and here we are.”

The American’s face showed his

surprise and admiration. The American’s face showed his

surprise and admiration.

“My, but that was smart! You had it

down to a fine thing.” “My, but that was smart! You had it

down to a fine thing.”

“Yes, a few of us even then could

have guessed the date. Here it is, and I’m shutting down to-morrow morning.” “Yes, a few of us even then could

have guessed the date. Here it is, and I’m shutting down to-morrow morning.”

“Well, I guess you’ll have to

fix me up also. I’m not staying in this gol-darned country all on my lonesome. In a

week or less, from what I see, John Bull will be on his hind legs and fair ramping.

I’d rather watch him from over the water.” “Well, I guess you’ll have to

fix me up also. I’m not staying in this gol-darned country all on my lonesome. In a

week or less, from what I see, John Bull will be on his hind legs and fair ramping.

I’d rather watch him from over the water.”

“But you’re an American

citizen?” “But you’re an American

citizen?”

“Well, so was Jack James an American

citizen, but he’s doing time in Portland all the same. It cuts no ice with a British

copper to tell him you’re an American citizen. ‘It’s British law and order

over here,’ says he. By the way, mister, talking of Jack James, it seems to me you

don’t do much to cover your men.” “Well, so was Jack James an American

citizen, but he’s doing time in Portland all the same. It cuts no ice with a British

copper to tell him you’re an American citizen. ‘It’s British law and order

over here,’ says he. By the way, mister, talking of Jack James, it seems to me you

don’t do much to cover your men.”

“What do you mean?” Von Bork

asked sharply. “What do you mean?” Von Bork

asked sharply.

[976] “Well, you are their employer, ain’t you?

It’s up to you to see that they don’t fall down. But they do fall down, and when

did you ever pick them up? There’s James– –” [976] “Well, you are their employer, ain’t you?

It’s up to you to see that they don’t fall down. But they do fall down, and when

did you ever pick them up? There’s James– –”

“It was James’s own fault. You

know that yourself. He was too self-willed for the job.” “It was James’s own fault. You

know that yourself. He was too self-willed for the job.”

“James was a bonehead–I give

you that. Then there was Hollis.” “James was a bonehead–I give

you that. Then there was Hollis.”

“The man was mad.” “The man was mad.”

“Well, he went a bit woozy towards

the end. It’s enough to make a man bughouse when he has to play a part from morning

to night with a hundred guys all ready to set the coppers wise to him. But now there is

Steiner– –” “Well, he went a bit woozy towards

the end. It’s enough to make a man bughouse when he has to play a part from morning

to night with a hundred guys all ready to set the coppers wise to him. But now there is

Steiner– –”

Von Bork started violently, and his ruddy

face turned a shade paler. Von Bork started violently, and his ruddy

face turned a shade paler.

“What about Steiner?” “What about Steiner?”

“Well, they’ve got him,

that’s all. They raided his store last night, and he and his papers are all in

Portsmouth jail. You’ll go off and he, poor devil, will have to stand the racket, and

lucky if he gets off with his life. That’s why I want to get over the water as soon

as you do.” “Well, they’ve got him,

that’s all. They raided his store last night, and he and his papers are all in

Portsmouth jail. You’ll go off and he, poor devil, will have to stand the racket, and

lucky if he gets off with his life. That’s why I want to get over the water as soon

as you do.”

Von Bork was a strong, self-contained

man, but it was easy to see that the news had shaken him. Von Bork was a strong, self-contained

man, but it was easy to see that the news had shaken him.

“How could they have got on to

Steiner?” he muttered. “That’s the worst blow yet.” “How could they have got on to

Steiner?” he muttered. “That’s the worst blow yet.”

“Well, you nearly had a worse one,

for I believe they are not far off me.” “Well, you nearly had a worse one,

for I believe they are not far off me.”

“You don’t mean that!” “You don’t mean that!”

“Sure thing. My landlady down

Fratton way had some inquiries, and when I heard of it I guessed it was time for me to

hustle. But what I want to know, mister, is how the coppers know these things? Steiner is

the fifth man you’ve lost since I signed on with you, and I know the name of the

sixth if I don’t get a move on. How do you explain it, and ain’t you ashamed to

see your men go down like this?” “Sure thing. My landlady down

Fratton way had some inquiries, and when I heard of it I guessed it was time for me to

hustle. But what I want to know, mister, is how the coppers know these things? Steiner is

the fifth man you’ve lost since I signed on with you, and I know the name of the

sixth if I don’t get a move on. How do you explain it, and ain’t you ashamed to

see your men go down like this?”

Von Bork flushed crimson. Von Bork flushed crimson.

“How dare you speak in such a

way!” “How dare you speak in such a

way!”

“If I didn’t dare things,

mister, I wouldn’t be in your service. But I’ll tell you straight what is in my

mind. I’ve heard that with you German politicians when an agent has done his work you

are not sorry to see him put away.” “If I didn’t dare things,

mister, I wouldn’t be in your service. But I’ll tell you straight what is in my

mind. I’ve heard that with you German politicians when an agent has done his work you

are not sorry to see him put away.”

Von Bork sprang to his feet. Von Bork sprang to his feet.

“Do you dare to suggest that I have

given away my own agents!” “Do you dare to suggest that I have

given away my own agents!”

“I don’t stand for that,

mister, but there’s a stool pigeon or a cross somewhere, and it’s up to you to

find out where it is. Anyhow I am taking no more chances. It’s me for little Holland,

and the sooner the better.” “I don’t stand for that,

mister, but there’s a stool pigeon or a cross somewhere, and it’s up to you to

find out where it is. Anyhow I am taking no more chances. It’s me for little Holland,

and the sooner the better.”

Von Bork had mastered his anger. Von Bork had mastered his anger.

“We have been allies too long to

quarrel now at the very hour of victory,” he said. “You’ve done splendid

work and taken risks, and I can’t forget it. By all means go to Holland, and you can

get a boat from Rotterdam to New York. No other line will be safe a week from now.

I’ll take that book and pack it with the rest.” “We have been allies too long to

quarrel now at the very hour of victory,” he said. “You’ve done splendid

work and taken risks, and I can’t forget it. By all means go to Holland, and you can

get a boat from Rotterdam to New York. No other line will be safe a week from now.

I’ll take that book and pack it with the rest.”

The American held the small parcel in his

hand, but made no motion to give it up. The American held the small parcel in his

hand, but made no motion to give it up.

“What about the dough?” he

asked. “What about the dough?” he

asked.

“The what?” “The what?”

“The boodle. The reward. The ´┐Ż500.

The gunner turned damned nasty at the last, and I had to square him with an extra hundred

dollars or it would have been nitsky for you and me. ‘Nothin’ doin’!’

says he, and he meant it, too, but the last [977]

hundred did it. It’s cost me two hundred pound from first to last, so

it isn’t likely I’d give it up without gettin’ my wad.” “The boodle. The reward. The ´┐Ż500.

The gunner turned damned nasty at the last, and I had to square him with an extra hundred

dollars or it would have been nitsky for you and me. ‘Nothin’ doin’!’

says he, and he meant it, too, but the last [977]

hundred did it. It’s cost me two hundred pound from first to last, so

it isn’t likely I’d give it up without gettin’ my wad.”

Von Bork smiled with some bitterness.

“You don’t seem to have a very high opinion of my honour,” said he,

“you want the money before you give up the book.” Von Bork smiled with some bitterness.

“You don’t seem to have a very high opinion of my honour,” said he,

“you want the money before you give up the book.”

“Well, mister, it is a business

proposition.” “Well, mister, it is a business

proposition.”

“All right. Have your way.” He

sat down at the table and scribbled a check, which he tore from the book, but he refrained

from handing it to his companion. “After all, since we are to be on such terms, Mr.

Altamont,” said he, “I don’t see why I should trust you any more than you

trust me. Do you understand?” he added, looking back over his shoulder at the

American. “There’s the check upon the table. I claim the right to examine that

parcel before you pick the money up.” “All right. Have your way.” He

sat down at the table and scribbled a check, which he tore from the book, but he refrained

from handing it to his companion. “After all, since we are to be on such terms, Mr.

Altamont,” said he, “I don’t see why I should trust you any more than you

trust me. Do you understand?” he added, looking back over his shoulder at the

American. “There’s the check upon the table. I claim the right to examine that

parcel before you pick the money up.”

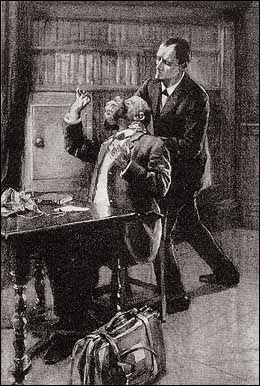

The American passed it over without a

word. Von Bork undid a winding of string and two wrappers of paper. Then he sat gazing for

a moment in silent amazement at a small blue book which lay before him. Across the cover

was printed in golden letters Practical Handbook of Bee Culture. Only for one

instant did the master spy glare at this strangely irrelevant inscription. The next he was

gripped at the back of his neck by a grasp of iron, and a chloroformed sponge was held in

front of his writhing face. The American passed it over without a

word. Von Bork undid a winding of string and two wrappers of paper. Then he sat gazing for

a moment in silent amazement at a small blue book which lay before him. Across the cover

was printed in golden letters Practical Handbook of Bee Culture. Only for one

instant did the master spy glare at this strangely irrelevant inscription. The next he was

gripped at the back of his neck by a grasp of iron, and a chloroformed sponge was held in

front of his writhing face.

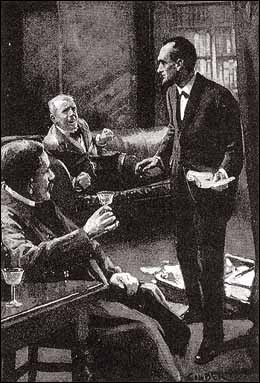

“Another glass, Watson!”

said Mr. Sherlock Holmes as he extended the bottle of Imperial Tokay. “Another glass, Watson!”

said Mr. Sherlock Holmes as he extended the bottle of Imperial Tokay.

The thickset chauffeur, who had seated

himself by the table, pushed forward his glass with some eagerness. The thickset chauffeur, who had seated

himself by the table, pushed forward his glass with some eagerness.

“It is a good wine, Holmes.” “It is a good wine, Holmes.”

“A remarkable wine, Watson. Our

friend upon the sofa has assured me that it is from Franz Josef’s special cellar at

the Schoenbrunn Palace. Might I trouble you to open the window, for chloroform vapour does

not help the palate.” “A remarkable wine, Watson. Our

friend upon the sofa has assured me that it is from Franz Josef’s special cellar at

the Schoenbrunn Palace. Might I trouble you to open the window, for chloroform vapour does

not help the palate.”

The safe was ajar, and Holmes standing in

front of it was removing dossier after dossier, swiftly examining each, and then packing

it neatly in Von Bork’s valise. The German lay upon the sofa sleeping stertorously

with a strap round his upper arms and another round his legs. The safe was ajar, and Holmes standing in

front of it was removing dossier after dossier, swiftly examining each, and then packing

it neatly in Von Bork’s valise. The German lay upon the sofa sleeping stertorously

with a strap round his upper arms and another round his legs.

“We need not hurry ourselves,

Watson. We are safe from interruption. Would you mind touching the bell? There is no one

in the house except old Martha, who has played her part to admiration. I got her the

situation here when first I took the matter up. Ah, Martha, you will be glad to hear that

all is well.” “We need not hurry ourselves,

Watson. We are safe from interruption. Would you mind touching the bell? There is no one

in the house except old Martha, who has played her part to admiration. I got her the

situation here when first I took the matter up. Ah, Martha, you will be glad to hear that

all is well.”

The pleasant old lady had appeared in the

doorway. She curtseyed with a smile to Mr. Holmes, but glanced with some apprehension at

the figure upon the sofa. The pleasant old lady had appeared in the

doorway. She curtseyed with a smile to Mr. Holmes, but glanced with some apprehension at

the figure upon the sofa.

“It is all right, Martha. He has not

been hurt at all.” “It is all right, Martha. He has not

been hurt at all.”

“I am glad of that, Mr. Holmes.

According to his lights he has been a kind master. He wanted me to go with his wife to

Germany yesterday, but that would hardly have suited your plans, would it, sir?” “I am glad of that, Mr. Holmes.

According to his lights he has been a kind master. He wanted me to go with his wife to

Germany yesterday, but that would hardly have suited your plans, would it, sir?”

“No, indeed, Martha. So long as you

were here I was easy in my mind. We waited some time for your signal to-night.” “No, indeed, Martha. So long as you

were here I was easy in my mind. We waited some time for your signal to-night.”

“It was the secretary, sir.” “It was the secretary, sir.”

“I know. His car passed ours.” “I know. His car passed ours.”

“I thought he would never go. I knew

that it would not suit your plans, sir, to find him here.” “I thought he would never go. I knew

that it would not suit your plans, sir, to find him here.”

“No, indeed. Well, it only meant

that we waited half an hour or so until I [978]

saw your lamp go out and knew that the coast was clear. You can report to

me to-morrow in London, Martha, at Claridge’s Hotel.” “No, indeed. Well, it only meant

that we waited half an hour or so until I [978]

saw your lamp go out and knew that the coast was clear. You can report to

me to-morrow in London, Martha, at Claridge’s Hotel.”

“Very good, sir.” “Very good, sir.”

“I suppose you have everything ready

to leave.” “I suppose you have everything ready

to leave.”

“Yes, sir. He posted seven letters

to-day. I have the addresses as usual.” “Yes, sir. He posted seven letters

to-day. I have the addresses as usual.”

“Very good, Martha. I will look into

them to-morrow. Good-night. These papers,” he continued as the old lady vanished,

“are not of very great importance, for, of course, the information which they

represent has been sent off long ago to the German government. These are the originals

which could not safely be got out of the country.” “Very good, Martha. I will look into

them to-morrow. Good-night. These papers,” he continued as the old lady vanished,

“are not of very great importance, for, of course, the information which they

represent has been sent off long ago to the German government. These are the originals

which could not safely be got out of the country.”

“Then they are of no use.” “Then they are of no use.”

“I should not go so far as to say

that, Watson. They will at least show our people what is known and what is not. I may say

that a good many of these papers have come through me, and I need not add are thoroughly

untrustworthy. It would brighten my declining years to see a German cruiser navigating the

Solent according to the mine-field plans which I have furnished. But you,

Watson”–he stopped his work and took his old friend by the

shoulders–“I’ve hardly seen you in the light yet. How have the years used

you? You look the same blithe boy as ever.” “I should not go so far as to say

that, Watson. They will at least show our people what is known and what is not. I may say

that a good many of these papers have come through me, and I need not add are thoroughly

untrustworthy. It would brighten my declining years to see a German cruiser navigating the

Solent according to the mine-field plans which I have furnished. But you,

Watson”–he stopped his work and took his old friend by the

shoulders–“I’ve hardly seen you in the light yet. How have the years used

you? You look the same blithe boy as ever.”

“I feel twenty years younger,

Holmes. I have seldom felt so happy as when I got your wire asking me to meet you at

Harwich with the car. But you, Holmes –you have changed very little–save for

that horrible goatee.” “I feel twenty years younger,

Holmes. I have seldom felt so happy as when I got your wire asking me to meet you at

Harwich with the car. But you, Holmes –you have changed very little–save for

that horrible goatee.”

“These are the sacrifices one makes

for one’s country, Watson,” said Holmes, pulling at his little tuft.

“To-morrow it will be but a dreadful memory. With my hair cut and a few other

superficial changes I shall no doubt reappear at Claridge’s to-morrow as I was before

this American stunt–I beg your pardon, Watson, my well of English seems to be

permanently defiled– before this American job came my way.” “These are the sacrifices one makes

for one’s country, Watson,” said Holmes, pulling at his little tuft.

“To-morrow it will be but a dreadful memory. With my hair cut and a few other

superficial changes I shall no doubt reappear at Claridge’s to-morrow as I was before

this American stunt–I beg your pardon, Watson, my well of English seems to be

permanently defiled– before this American job came my way.”

“But you have retired, Holmes. We

heard of you as living the life of a hermit among your bees and your books in a small farm

upon the South Downs.” “But you have retired, Holmes. We

heard of you as living the life of a hermit among your bees and your books in a small farm

upon the South Downs.”

“Exactly, Watson. Here is the fruit

of my leisured ease, the magnum opus of my latter years!” He picked up the

volume from the table and read out the whole title, Practical Handbook of Bee Culture,

with Some Observations upon the Segregation of the Queen. “Alone I did it.

Behold the fruit of pensive nights and laborious days when I watched the little working

gangs as once I watched the criminal world of London.” “Exactly, Watson. Here is the fruit

of my leisured ease, the magnum opus of my latter years!” He picked up the

volume from the table and read out the whole title, Practical Handbook of Bee Culture,

with Some Observations upon the Segregation of the Queen. “Alone I did it.

Behold the fruit of pensive nights and laborious days when I watched the little working

gangs as once I watched the criminal world of London.”

“But how did you get to work

again?” “But how did you get to work

again?”

“Ah, I have often marvelled at it

myself. The Foreign Minister alone I could have withstood, but when the Premier also

deigned to visit my humble roof– –! The fact is, Watson, that this gentleman

upon the sofa was a bit too good for our people. He was in a class by himself. Things were

going wrong, and no one could understand why they were going wrong. Agents were suspected

or even caught, but there was evidence of some strong and secret central force. It was

absolutely necessary to expose it. Strong pressure was brought upon me to look into the

matter. It has cost me two years, Watson, but they have not been devoid of excitement.

When I say that I started my pilgrimage at Chicago, graduated in an Irish secret society

at Buffalo, gave serious trouble to the constabulary at Skibbareen, and so eventually

caught the eye of a subordinate agent of Von Bork, who recommended me as a likely man, you

will realize that the matter was complex. Since then I have been honoured by his

confidence, which has not prevented most of his plans going subtly wrong and five of his

best agents being in prison. [979] I

watched them, Watson, and I picked them as they ripened. Well, sir, I hope that you are

none the worse!” “Ah, I have often marvelled at it

myself. The Foreign Minister alone I could have withstood, but when the Premier also

deigned to visit my humble roof– –! The fact is, Watson, that this gentleman

upon the sofa was a bit too good for our people. He was in a class by himself. Things were

going wrong, and no one could understand why they were going wrong. Agents were suspected

or even caught, but there was evidence of some strong and secret central force. It was

absolutely necessary to expose it. Strong pressure was brought upon me to look into the

matter. It has cost me two years, Watson, but they have not been devoid of excitement.

When I say that I started my pilgrimage at Chicago, graduated in an Irish secret society

at Buffalo, gave serious trouble to the constabulary at Skibbareen, and so eventually

caught the eye of a subordinate agent of Von Bork, who recommended me as a likely man, you

will realize that the matter was complex. Since then I have been honoured by his

confidence, which has not prevented most of his plans going subtly wrong and five of his

best agents being in prison. [979] I

watched them, Watson, and I picked them as they ripened. Well, sir, I hope that you are

none the worse!”

The last remark was addressed to Von Bork

himself, who after much gasping and blinking had lain quietly listening to Holmes’s

statement. He broke out now into a furious stream of German invective, his face convulsed

with passion. Holmes continued his swift investigation of documents while his prisoner

cursed and swore. The last remark was addressed to Von Bork

himself, who after much gasping and blinking had lain quietly listening to Holmes’s

statement. He broke out now into a furious stream of German invective, his face convulsed

with passion. Holmes continued his swift investigation of documents while his prisoner

cursed and swore.

“Though unmusical, German is the

most expressive of all languages,” he observed when Von Bork had stopped from pure

exhaustion. “Hullo! Hullo!” he added as he looked hard at the corner of a

tracing before putting it in the box. “This should put another bird in the cage. I

had no idea that the paymaster was such a rascal, though I have long had an eye upon him.

Mister Von Bork, you have a great deal to answer for.” “Though unmusical, German is the

most expressive of all languages,” he observed when Von Bork had stopped from pure

exhaustion. “Hullo! Hullo!” he added as he looked hard at the corner of a

tracing before putting it in the box. “This should put another bird in the cage. I

had no idea that the paymaster was such a rascal, though I have long had an eye upon him.

Mister Von Bork, you have a great deal to answer for.”

The prisoner had raised himself with some

difficulty upon the sofa and was staring with a strange mixture of amazement and hatred at

his captor. The prisoner had raised himself with some

difficulty upon the sofa and was staring with a strange mixture of amazement and hatred at

his captor.

“I shall get level with you,

Altamont,” he said, speaking with slow deliberation. “If it takes me all my life

I shall get level with you!” “I shall get level with you,

Altamont,” he said, speaking with slow deliberation. “If it takes me all my life

I shall get level with you!”

“The old sweet song,” said

Holmes. “How often have I heard it in days gone by. It was a favourite ditty of the

late lamented Professor Moriarty. Colonel Sebastian Moran has also been known to warble

it. And yet I live and keep bees upon the South Downs.” “The old sweet song,” said

Holmes. “How often have I heard it in days gone by. It was a favourite ditty of the

late lamented Professor Moriarty. Colonel Sebastian Moran has also been known to warble

it. And yet I live and keep bees upon the South Downs.”

“Curse you, you double

traitor!” cried the German, straining against his bonds and glaring murder from his

furious eyes. “Curse you, you double

traitor!” cried the German, straining against his bonds and glaring murder from his

furious eyes.

“No, no, it is not so bad as

that,” said Holmes, smiling. “As my speech surely shows you, Mr. Altamont of

Chicago had no existence in fact. I used him and he is gone.” “No, no, it is not so bad as

that,” said Holmes, smiling. “As my speech surely shows you, Mr. Altamont of

Chicago had no existence in fact. I used him and he is gone.”

“Then who are you?” “Then who are you?”

“It is really immaterial who I am,

but since the matter seems to interest you, Mr. Von Bork, I may say that this is not my

first acquaintance with the members of your family. I have done a good deal of business in

Germany in the past and my name is probably familiar to you.” “It is really immaterial who I am,

but since the matter seems to interest you, Mr. Von Bork, I may say that this is not my

first acquaintance with the members of your family. I have done a good deal of business in

Germany in the past and my name is probably familiar to you.”

“I would wish to know it,” said

the Prussian grimly. “I would wish to know it,” said

the Prussian grimly.

“It was I who brought about the

separation between Irene Adler and the late King of Bohemia when your cousin Heinrich was

the Imperial Envoy. It was I also who saved from murder, by the Nihilist Klopman, Count

Von und Zu Grafenstein, who was your mother’s elder brother. It was I–

–” “It was I who brought about the

separation between Irene Adler and the late King of Bohemia when your cousin Heinrich was

the Imperial Envoy. It was I also who saved from murder, by the Nihilist Klopman, Count

Von und Zu Grafenstein, who was your mother’s elder brother. It was I–

–”

Von Bork sat up in amazement. Von Bork sat up in amazement.

“There is only one man,” he

cried. “There is only one man,” he

cried.

“Exactly,” said Holmes. “Exactly,” said Holmes.

Von Bork groaned and sank back on the

sofa. “And most of that information came through you,” he cried. “What is

it worth? What have I done? It is my ruin forever!” Von Bork groaned and sank back on the

sofa. “And most of that information came through you,” he cried. “What is

it worth? What have I done? It is my ruin forever!”

“It is certainly a little

untrustworthy,” said Holmes. “It will require some checking and you have little

time to check it. Your admiral may find the new guns rather larger than he expects, and

the cruisers perhaps a trifle faster.” “It is certainly a little

untrustworthy,” said Holmes. “It will require some checking and you have little

time to check it. Your admiral may find the new guns rather larger than he expects, and

the cruisers perhaps a trifle faster.”

Von Bork clutched at his own throat in

despair. Von Bork clutched at his own throat in

despair.

“There are a good many other points

of detail which will, no doubt, come to light in good time. But you have one quality which

is very rare in a German, Mr. Von Bork: you are a sportsman and you will bear me no

ill-will when you realize that you, who have outwitted so many other people, have at last

been outwitted yourself. After all, you have done your best for your country, and I have

done my [980] best for mine,

and what could be more natural? Besides,” he added, not unkindly, as he laid his hand

upon the shoulder of the prostrate man, “it is better than to fall before some more

ignoble foe. These papers are now ready, Watson. If you will help me with our prisoner, I

think that we may get started for London at once.” “There are a good many other points

of detail which will, no doubt, come to light in good time. But you have one quality which

is very rare in a German, Mr. Von Bork: you are a sportsman and you will bear me no

ill-will when you realize that you, who have outwitted so many other people, have at last

been outwitted yourself. After all, you have done your best for your country, and I have

done my [980] best for mine,

and what could be more natural? Besides,” he added, not unkindly, as he laid his hand

upon the shoulder of the prostrate man, “it is better than to fall before some more

ignoble foe. These papers are now ready, Watson. If you will help me with our prisoner, I

think that we may get started for London at once.”

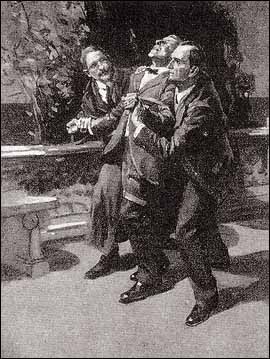

It was no easy task to move Von Bork,

for he was a strong and a desperate man. Finally, holding either arm, the two friends

walked him very slowly down the garden walk which he had trod with such proud confidence

when he received the congratulations of the famous diplomatist only a few hours before.

After a short, final struggle he was hoisted, still bound hand and foot, into the spare

seat of the little car. His precious valise was wedged in beside him. It was no easy task to move Von Bork,

for he was a strong and a desperate man. Finally, holding either arm, the two friends

walked him very slowly down the garden walk which he had trod with such proud confidence

when he received the congratulations of the famous diplomatist only a few hours before.

After a short, final struggle he was hoisted, still bound hand and foot, into the spare

seat of the little car. His precious valise was wedged in beside him.

“I trust that you are as comfortable

as circumstances permit,” said Holmes when the final arrangements were made.

“Should I be guilty of a liberty if I lit a cigar and placed it between your

lips?” “I trust that you are as comfortable

as circumstances permit,” said Holmes when the final arrangements were made.

“Should I be guilty of a liberty if I lit a cigar and placed it between your

lips?”

But all amenities were wasted upon the

angry German. But all amenities were wasted upon the

angry German.

“I suppose you realize, Mr. Sherlock

Holmes,” said he, “that if your government bears you out in this treatment it

becomes an act of war.” “I suppose you realize, Mr. Sherlock

Holmes,” said he, “that if your government bears you out in this treatment it

becomes an act of war.”

“What about your government and all

this treatment?” said Holmes, tapping the valise. “What about your government and all

this treatment?” said Holmes, tapping the valise.

“You are a private individual. You

have no warrant for my arrest. The whole proceeding is absolutely illegal and

outrageous.” “You are a private individual. You

have no warrant for my arrest. The whole proceeding is absolutely illegal and

outrageous.”

“Absolutely,” said Holmes. “Absolutely,” said Holmes.

“Kidnapping a German subject.” “Kidnapping a German subject.”

“And stealing his private

papers.” “And stealing his private

papers.”

“Well, you realize your position,

you and your accomplice here. If I were to shout for help as we pass through the

village– –” “Well, you realize your position,

you and your accomplice here. If I were to shout for help as we pass through the

village– –”

“My dear sir, if you did anything so

foolish you would probably enlarge the two limited titles of our village inns by giving us

‘The Dangling Prussian’ as a signpost. The Englishman is a patient creature, but

at present his temper is a little inflamed, and it would be as well not to try him too

far. No, Mr. Von Bork, you will go with us in a quiet, sensible fashion to Scotland Yard,

whence you can send for your friend, Baron Von Herling, and see if even now you may not

fill that place which he has reserved for you in the ambassadorial suite. As to you,

Watson, you are joining us with your old service, as I understand, so London won’t be

out of your way. Stand with me here upon the terrace, for it may be the last quiet talk

that we shall ever have.” “My dear sir, if you did anything so

foolish you would probably enlarge the two limited titles of our village inns by giving us

‘The Dangling Prussian’ as a signpost. The Englishman is a patient creature, but

at present his temper is a little inflamed, and it would be as well not to try him too

far. No, Mr. Von Bork, you will go with us in a quiet, sensible fashion to Scotland Yard,

whence you can send for your friend, Baron Von Herling, and see if even now you may not

fill that place which he has reserved for you in the ambassadorial suite. As to you,

Watson, you are joining us with your old service, as I understand, so London won’t be

out of your way. Stand with me here upon the terrace, for it may be the last quiet talk

that we shall ever have.”

The two friends chatted in intimate

converse for a few minutes, recalling once again the days of the past, while their

prisoner vainly wriggled to undo the bonds that held him. As they turned to the car Holmes

pointed back to the moonlit sea and shook a thoughtful head. The two friends chatted in intimate

converse for a few minutes, recalling once again the days of the past, while their

prisoner vainly wriggled to undo the bonds that held him. As they turned to the car Holmes

pointed back to the moonlit sea and shook a thoughtful head.

“There’s an east wind coming,

Watson.” “There’s an east wind coming,

Watson.”

“I think not, Holmes. It is very

warm.” “I think not, Holmes. It is very

warm.”

“Good old Watson! You are the one

fixed point in a changing age. There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind

as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us

may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a

cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared. Start

her up, Watson, for it’s time that we were on our way. I have a check for five

hundred pounds which should be cashed early, for the drawer is quite capable of stopping

it if he can.” “Good old Watson! You are the one

fixed point in a changing age. There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind

as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us

may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a

cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared. Start

her up, Watson, for it’s time that we were on our way. I have a check for five

hundred pounds which should be cashed early, for the drawer is quite capable of stopping

it if he can.”

|

![]() A remarkable man this Von Bork–a man

who could hardly be matched among all the devoted agents of the Kaiser. It was his talents

which had first recommended him for the English mission, the most important mission of

all, but since he had taken it over those talents had become more and more manifest to the

half-dozen people in the world who were really in touch with the truth. One of these was

his present companion, Baron Von Herling, the chief secretary of the legation, whose huge

100-horse-power Benz car was blocking the country lane as it waited to waft its owner back

to London.

A remarkable man this Von Bork–a man

who could hardly be matched among all the devoted agents of the Kaiser. It was his talents

which had first recommended him for the English mission, the most important mission of

all, but since he had taken it over those talents had become more and more manifest to the

half-dozen people in the world who were really in touch with the truth. One of these was

his present companion, Baron Von Herling, the chief secretary of the legation, whose huge

100-horse-power Benz car was blocking the country lane as it waited to waft its owner back

to London.![]() “So far as I can judge the trend of

events, you will probably be back in Berlin within the week,” the secretary was

saying. “When you get there, my dear Von Bork, I think you will be surprised at the

welcome you will receive. I happen to know what is thought in the highest quarters of your

work in this country.” He was a huge man, the secretary, deep, broad, and tall, with

a slow, heavy fashion of speech which had been his main asset in his political career.

“So far as I can judge the trend of

events, you will probably be back in Berlin within the week,” the secretary was

saying. “When you get there, my dear Von Bork, I think you will be surprised at the

welcome you will receive. I happen to know what is thought in the highest quarters of your

work in this country.” He was a huge man, the secretary, deep, broad, and tall, with

a slow, heavy fashion of speech which had been his main asset in his political career.![]() Von Bork laughed.

Von Bork laughed.![]() “They are not very hard to

deceive,” he remarked. “A more docile, simple folk could not be imagined.”

“They are not very hard to

deceive,” he remarked. “A more docile, simple folk could not be imagined.”![]() “I don’t know about that,”

said the other thoughtfully. “They have strange limits and one must learn to observe

them. It is that surface simplicity of theirs which makes a trap for the stranger.

One’s first impression is that they are entirely soft. Then one comes suddenly upon

something very hard, and you know that you have reached the limit and must adapt yourself

to the fact. They have, for example, their insular conventions which simply must

be observed.”

“I don’t know about that,”

said the other thoughtfully. “They have strange limits and one must learn to observe

them. It is that surface simplicity of theirs which makes a trap for the stranger.

One’s first impression is that they are entirely soft. Then one comes suddenly upon

something very hard, and you know that you have reached the limit and must adapt yourself

to the fact. They have, for example, their insular conventions which simply must

be observed.”![]() “Meaning, ‘good form’ and

that sort of thing?” Von Bork sighed as one who had suffered much.

“Meaning, ‘good form’ and

that sort of thing?” Von Bork sighed as one who had suffered much.![]() “Meaning British prejudice in all

its queer manifestations. As an example I may quote one of my own worst blunders–I

can afford to talk of my blunders, for you know my work well enough to be aware of my

successes. It was on my first arrival. I was invited to a week-end gathering at the

country house of a cabinet minister. The conversation was amazingly indiscreet.”

“Meaning British prejudice in all

its queer manifestations. As an example I may quote one of my own worst blunders–I

can afford to talk of my blunders, for you know my work well enough to be aware of my

successes. It was on my first arrival. I was invited to a week-end gathering at the

country house of a cabinet minister. The conversation was amazingly indiscreet.”![]() Von Bork nodded. “I’ve been

there,” said he dryly.

Von Bork nodded. “I’ve been

there,” said he dryly.![]() “Exactly. Well, I naturally sent a

r´┐Żsum´┐Ż of the information to Berlin. Unfortunately our good chancellor is a little

heavy-handed in these matters, and he transmitted a remark which showed that he was aware

of what had been said. This, of course, took the trail straight up to me. You’ve no

idea the harm that it did me. There was nothing soft about our British hosts on that

occasion, I can assure you. I was two years living it down. Now you, with this sporting

pose of yours– –”

“Exactly. Well, I naturally sent a

r´┐Żsum´┐Ż of the information to Berlin. Unfortunately our good chancellor is a little

heavy-handed in these matters, and he transmitted a remark which showed that he was aware

of what had been said. This, of course, took the trail straight up to me. You’ve no

idea the harm that it did me. There was nothing soft about our British hosts on that

occasion, I can assure you. I was two years living it down. Now you, with this sporting

pose of yours– –”![]() “No, no, don’t call it a pose.

A pose is an artificial thing. This is quite natural. I am a born sportsman. I enjoy

it.”

“No, no, don’t call it a pose.

A pose is an artificial thing. This is quite natural. I am a born sportsman. I enjoy

it.”![]() “Well, that makes it the more

effective. You yacht against them, you hunt with them, you play polo, you match them in

every game, your four-in-hand takes the [972]

prize at Olympia. I have even heard that you go the length of boxing with

the young officers. What is the result? Nobody takes you seriously. You are a ‘good

old sport,’ ‘quite a decent fellow for a German,’ a hard-drinking,

night-club, knock-about-town, devil-may-care young fellow. And all the time this quiet

country house of yours is the centre of half the mischief in England, and the sporting

squire the most astute secret-service man in Europe. Genius, my dear Von

Bork–genius!”

“Well, that makes it the more

effective. You yacht against them, you hunt with them, you play polo, you match them in

every game, your four-in-hand takes the [972]

prize at Olympia. I have even heard that you go the length of boxing with

the young officers. What is the result? Nobody takes you seriously. You are a ‘good

old sport,’ ‘quite a decent fellow for a German,’ a hard-drinking,

night-club, knock-about-town, devil-may-care young fellow. And all the time this quiet

country house of yours is the centre of half the mischief in England, and the sporting

squire the most astute secret-service man in Europe. Genius, my dear Von

Bork–genius!”![]() “You flatter me, Baron. But

certainly I may claim that my four years in this country have not been unproductive.

I’ve never shown you my little store. Would you mind stepping in for a moment?”

“You flatter me, Baron. But

certainly I may claim that my four years in this country have not been unproductive.

I’ve never shown you my little store. Would you mind stepping in for a moment?”![]() The door of the study opened straight on

to the terrace. Von Bork pushed it back, and, leading the way, he clicked the switch of

the electric light. He then closed the door behind the bulky form which followed him and

carefully adjusted the heavy curtain over the latticed window. Only when all these

precautions had been taken and tested did he turn his sunburned aquiline face to his

guest.

The door of the study opened straight on

to the terrace. Von Bork pushed it back, and, leading the way, he clicked the switch of

the electric light. He then closed the door behind the bulky form which followed him and

carefully adjusted the heavy curtain over the latticed window. Only when all these

precautions had been taken and tested did he turn his sunburned aquiline face to his

guest.![]() “Some of my papers have gone,”

said he. “When my wife and the household left yesterday for Flushing they took the

less important with them. I must, of course, claim the protection of the embassy for the

others.”

“Some of my papers have gone,”

said he. “When my wife and the household left yesterday for Flushing they took the

less important with them. I must, of course, claim the protection of the embassy for the

others.”![]() “Your name has already been filed as

one of the personal suite. There will be no difficulties for you or your baggage. Of

course, it is just possible that we may not have to go. England may leave France to her

fate. We are sure that there is no binding treaty between them.”

“Your name has already been filed as

one of the personal suite. There will be no difficulties for you or your baggage. Of

course, it is just possible that we may not have to go. England may leave France to her

fate. We are sure that there is no binding treaty between them.”![]() “And Belgium?”

“And Belgium?”![]() “Yes, and Belgium, too.”

“Yes, and Belgium, too.”![]() Von Bork shook his head. “I

don’t see how that could be. There is a definite treaty there. She could never

recover from such a humiliation.”

Von Bork shook his head. “I

don’t see how that could be. There is a definite treaty there. She could never

recover from such a humiliation.”![]() “She would at least have peace for

the moment.”

“She would at least have peace for

the moment.”![]() “But her honour?”

“But her honour?”![]() “Tut, my dear sir, we live in a

utilitarian age. Honour is a mediaeval conception. Besides England is not ready. It is an

inconceivable thing, but even our special war tax of fifty million, which one would think

made our purpose as clear as if we had advertised it on the front page of the Times,

has not roused these people from their slumbers. Here and there one hears a question. It

is my business to find an answer. Here and there also there is an irritation. It is my

business to soothe it. But I can assure you that so far as the essentials go–the

storage of munitions, the preparation for submarine attack, the arrangements for making

high explosives–nothing is prepared. How, then, can England come in, especially when

we have stirred her up such a devil’s brew of Irish civil war, window-breaking

Furies, and God knows what to keep her thoughts at home.”

“Tut, my dear sir, we live in a

utilitarian age. Honour is a mediaeval conception. Besides England is not ready. It is an

inconceivable thing, but even our special war tax of fifty million, which one would think

made our purpose as clear as if we had advertised it on the front page of the Times,

has not roused these people from their slumbers. Here and there one hears a question. It

is my business to find an answer. Here and there also there is an irritation. It is my

business to soothe it. But I can assure you that so far as the essentials go–the

storage of munitions, the preparation for submarine attack, the arrangements for making

high explosives–nothing is prepared. How, then, can England come in, especially when

we have stirred her up such a devil’s brew of Irish civil war, window-breaking

Furies, and God knows what to keep her thoughts at home.”![]() “She must think of her future.”

“She must think of her future.”![]() “Ah, that is another matter. I fancy

that in the future we have our own very definite plans about England, and that your

information will be very vital to us. It is to-day or to-morrow with Mr. John Bull. If he

prefers to-day we are perfectly ready. If it is to-morrow we shall be more ready still. I

should think they would be wiser to fight with allies than without them, but that is their

own affair. This week is their week of destiny. But you were speaking of your

papers.” He sat in the armchair with the light shining upon his broad bald head,

while he puffed sedately at his cigar.

“Ah, that is another matter. I fancy

that in the future we have our own very definite plans about England, and that your

information will be very vital to us. It is to-day or to-morrow with Mr. John Bull. If he

prefers to-day we are perfectly ready. If it is to-morrow we shall be more ready still. I

should think they would be wiser to fight with allies than without them, but that is their

own affair. This week is their week of destiny. But you were speaking of your

papers.” He sat in the armchair with the light shining upon his broad bald head,

while he puffed sedately at his cigar.![]() The large oak-panelled, book-lined room

had a curtain hung in the further corner. When this was drawn it disclosed a large,

brass-bound safe. Von Bork [973] detached

a small key from his watch chain, and after some considerable manipulation of the lock he

swung open the heavy door.

The large oak-panelled, book-lined room

had a curtain hung in the further corner. When this was drawn it disclosed a large,

brass-bound safe. Von Bork [973] detached

a small key from his watch chain, and after some considerable manipulation of the lock he

swung open the heavy door.![]() “Look!” said he, standing

clear, with a wave of his hand.

“Look!” said he, standing

clear, with a wave of his hand.![]() The light shone vividly into the opened

safe, and the secretary of the embassy gazed with an absorbed interest at the rows of

stuffed pigeon-holes with which it was furnished. Each pigeon-hole had its label, and his

eyes as he glanced along them read a long series of such titles as “Fords,”

“Harbour-defences,” “Aeroplanes,” “Ireland,”

“Egypt,” “Portsmouth forts,” “The Channel,”

“Rosythe,” and a score of others. Each compartment was bristling with papers and

plans.

The light shone vividly into the opened

safe, and the secretary of the embassy gazed with an absorbed interest at the rows of

stuffed pigeon-holes with which it was furnished. Each pigeon-hole had its label, and his

eyes as he glanced along them read a long series of such titles as “Fords,”

“Harbour-defences,” “Aeroplanes,” “Ireland,”

“Egypt,” “Portsmouth forts,” “The Channel,”

“Rosythe,” and a score of others. Each compartment was bristling with papers and

plans.![]() “Colossal!” said the secretary.

Putting down his cigar he softly clapped his fat hands.

“Colossal!” said the secretary.

Putting down his cigar he softly clapped his fat hands.![]() “And all in four years, Baron. Not

such a bad show for the hard-drinking, hard-riding country squire. But the gem of my

collection is coming and there is the setting all ready for it.” He pointed to a

space over which “Naval Signals” was printed.

“And all in four years, Baron. Not

such a bad show for the hard-drinking, hard-riding country squire. But the gem of my

collection is coming and there is the setting all ready for it.” He pointed to a

space over which “Naval Signals” was printed.![]() “But you have a good dossier there

already.”

“But you have a good dossier there

already.”![]() “Out of date and waste paper. The

Admiralty in some way got the alarm and every code has been changed. It was a blow,

Baron–the worst setback in my whole campaign. But thanks to my check-book and the

good Altamont all will be well to-night.”

“Out of date and waste paper. The

Admiralty in some way got the alarm and every code has been changed. It was a blow,

Baron–the worst setback in my whole campaign. But thanks to my check-book and the

good Altamont all will be well to-night.”![]() The Baron looked at his watch and gave a

guttural exclamation of disappointment.

The Baron looked at his watch and gave a

guttural exclamation of disappointment.![]() “Well, I really can wait no longer.

You can imagine that things are moving at present in Carlton Terrace and that we have all

to be at our posts. I had hoped to be able to bring news of your great coup. Did Altamont

name no hour?”

“Well, I really can wait no longer.

You can imagine that things are moving at present in Carlton Terrace and that we have all

to be at our posts. I had hoped to be able to bring news of your great coup. Did Altamont

name no hour?”![]() Von Bork pushed over a telegram.

Von Bork pushed over a telegram.