|

|

“Dear me, Watson,” said Holmes, staring with great

curiosity at the slips of foolscap which the landlady had handed to him, “this is

certainly a little unusual. Seclusion I can understand; but why print? Printing is a

clumsy process. Why not write? What would it suggest, Watson?” “Dear me, Watson,” said Holmes, staring with great

curiosity at the slips of foolscap which the landlady had handed to him, “this is

certainly a little unusual. Seclusion I can understand; but why print? Printing is a

clumsy process. Why not write? What would it suggest, Watson?”

“That he desired to conceal his handwriting.” “That he desired to conceal his handwriting.”

“But why? What can it matter to him that his landlady

should have a word of his writing? Still, it may be as you say. Then, again, why such

laconic messages?” “But why? What can it matter to him that his landlady

should have a word of his writing? Still, it may be as you say. Then, again, why such

laconic messages?”

[903] “I

cannot imagine.” [903] “I

cannot imagine.”

“It opens a pleasing field for intelligent speculation.

The words are written with a broad-pointed, violet-tinted pencil of a not unusual pattern.

You will observe that the paper is torn away at the side here after the printing was done,

so that the ‘S’ of ‘SOAP’ is partly gone. Suggestive, Watson, is it

not?” “It opens a pleasing field for intelligent speculation.

The words are written with a broad-pointed, violet-tinted pencil of a not unusual pattern.

You will observe that the paper is torn away at the side here after the printing was done,

so that the ‘S’ of ‘SOAP’ is partly gone. Suggestive, Watson, is it

not?”

“Of caution?” “Of caution?”

“Exactly. There was evidently some mark, some thumbprint,

something which might give a clue to the person’s identity. Now, Mrs. Warren, you say

that the man was of middle size, dark, and bearded. What age would he be?” “Exactly. There was evidently some mark, some thumbprint,

something which might give a clue to the person’s identity. Now, Mrs. Warren, you say

that the man was of middle size, dark, and bearded. What age would he be?”

“Youngish, sir–not over thirty.” “Youngish, sir–not over thirty.”

“Well, can you give me no further indications?” “Well, can you give me no further indications?”

“He spoke good English, sir, and yet I thought he was a

foreigner by his accent.” “He spoke good English, sir, and yet I thought he was a

foreigner by his accent.”

“And he was well dressed?” “And he was well dressed?”

“Very smartly dressed, sir–quite the gentleman. Dark

clothes–nothing you would note.” “Very smartly dressed, sir–quite the gentleman. Dark

clothes–nothing you would note.”

“He gave no name?” “He gave no name?”

“No, sir.” “No, sir.”

“And has had no letters or callers?” “And has had no letters or callers?”

“None.” “None.”

“But surely you or the girl enter his room of a

morning?” “But surely you or the girl enter his room of a

morning?”

“No, sir; he looks after himself entirely.” “No, sir; he looks after himself entirely.”

“Dear me! that is certainly remarkable. What about his

luggage?” “Dear me! that is certainly remarkable. What about his

luggage?”

“He had one big brown bag with him–nothing

else.” “He had one big brown bag with him–nothing

else.”

“Well, we don’t seem to have much material to help

us. Do you say nothing has come out of that room–absolutely nothing?” “Well, we don’t seem to have much material to help

us. Do you say nothing has come out of that room–absolutely nothing?”

The landlady drew an envelope from her bag; from it she shook

out two burnt matches and a cigarette-end upon the table. The landlady drew an envelope from her bag; from it she shook

out two burnt matches and a cigarette-end upon the table.

“They were on his tray this morning. I brought them

because I had heard that you can read great things out of small ones.” “They were on his tray this morning. I brought them

because I had heard that you can read great things out of small ones.”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders. Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“There is nothing here,” said he. “The matches

have, of course, been used to light cigarettes. That is obvious from the shortness of the

burnt end. Half the match is consumed in lighting a pipe or cigar. But, dear me! this

cigarette stub is certainly remarkable. The gentleman was bearded and moustached, you

say?” “There is nothing here,” said he. “The matches

have, of course, been used to light cigarettes. That is obvious from the shortness of the

burnt end. Half the match is consumed in lighting a pipe or cigar. But, dear me! this

cigarette stub is certainly remarkable. The gentleman was bearded and moustached, you

say?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“I don’t understand that. I should say that only a

clean-shaven man could have smoked this. Why, Watson, even your modest moustache would

have been singed.” “I don’t understand that. I should say that only a

clean-shaven man could have smoked this. Why, Watson, even your modest moustache would

have been singed.”

“A holder?” I suggested. “A holder?” I suggested.

“No, no; the end is matted. I suppose there could not be

two people in your rooms, Mrs. Warren?” “No, no; the end is matted. I suppose there could not be

two people in your rooms, Mrs. Warren?”

“No, sir. He eats so little that I often wonder it can

keep life in one.” “No, sir. He eats so little that I often wonder it can

keep life in one.”

“Well, I think we must wait for a little more material.

After all, you have nothing to complain of. You have received your rent, and he is not a

troublesome lodger, though he is certainly an unusual one. He pays you well, and if he

chooses to lie concealed it is no direct business of yours. We have no excuse for an

intrusion upon his privacy until we have some reason to think that there is a guilty

reason for it. I’ve taken up the matter, and I won’t lose sight of it. Report to

me if anything fresh occurs, and rely upon my assistance if it should be needed. “Well, I think we must wait for a little more material.

After all, you have nothing to complain of. You have received your rent, and he is not a

troublesome lodger, though he is certainly an unusual one. He pays you well, and if he

chooses to lie concealed it is no direct business of yours. We have no excuse for an

intrusion upon his privacy until we have some reason to think that there is a guilty

reason for it. I’ve taken up the matter, and I won’t lose sight of it. Report to

me if anything fresh occurs, and rely upon my assistance if it should be needed.

[904] “There

are certainly some points of interest in this case, Watson,” he remarked when the

landlady had left us. “It may, of course, be trivial– individual eccentricity;

or it may be very much deeper than appears on the surface. The first thing that strikes

one is the obvious possibility that the person now in the rooms may be entirely different

from the one who engaged them.” [904] “There

are certainly some points of interest in this case, Watson,” he remarked when the

landlady had left us. “It may, of course, be trivial– individual eccentricity;

or it may be very much deeper than appears on the surface. The first thing that strikes

one is the obvious possibility that the person now in the rooms may be entirely different

from the one who engaged them.”

“Why should you think so?” “Why should you think so?”

“Well, apart from this cigarette-end, was it not

suggestive that the only time the lodger went out was immediately after his taking the

rooms? He came back–or someone came back–when all witnesses were out of the way.

We have no proof that the person who came back was the person who went out. Then, again,

the man who took the rooms spoke English well. This other, however, prints

‘match’ when it should have been ‘matches.’ I can imagine that the

word was taken out of a dictionary, which would give the noun but not the plural. The

laconic style may be to conceal the absence of knowledge of English. Yes, Watson, there

are good reasons to suspect that there has been a substitution of lodgers.” “Well, apart from this cigarette-end, was it not

suggestive that the only time the lodger went out was immediately after his taking the

rooms? He came back–or someone came back–when all witnesses were out of the way.

We have no proof that the person who came back was the person who went out. Then, again,

the man who took the rooms spoke English well. This other, however, prints

‘match’ when it should have been ‘matches.’ I can imagine that the

word was taken out of a dictionary, which would give the noun but not the plural. The

laconic style may be to conceal the absence of knowledge of English. Yes, Watson, there

are good reasons to suspect that there has been a substitution of lodgers.”

“But for what possible end?” “But for what possible end?”

“Ah! there lies our problem. There is one rather obvious

line of investigation.” He took down the great book in which, day by day, he filed

the agony columns of the various London journals. “Dear me!” said he, turning

over the pages, “what a chorus of groans, cries, and bleatings! What a rag-bag of

singular happenings! But surely the most valuable hunting-ground that ever was given to a

student of the unusual! This person is alone and cannot be approached by letter without a

breach of that absolute secrecy which is desired. How is any news or any message to reach

him from without? Obviously by advertisement through a newspaper. There seems no other

way, and fortunately we need concern ourselves with the one paper only. Here are the Daily

Gazette extracts of the last fortnight. ‘Lady with a black boa at Prince’s

Skating Club’–that we may pass. ‘Surely Jimmy will not break his

mother’s heart’– that appears to be irrelevant. ‘If the lady who

fainted in the Brixton bus’– she does not interest me. ‘Every day my heart

longs– –’ Bleat, Watson– unmitigated bleat! Ah, this is a little more

possible. Listen to this: ‘Be patient. Will find some sure means of communication.

Meanwhile, this column. G.’ That is two days after Mrs. Warren’s lodger arrived.

It sounds plausible, does it not? The mysterious one could understand English, even if he

could not print it. Let us see if we can pick up the trace again. Yes, here we are–

three days later. ‘Am making successful arrangements. Patience and prudence. The

clouds will pass. G.’ Nothing for a week after that. Then comes something much more

definite: ‘The path is clearing. If I find chance signal message remember code

agreed–one A, two B, and so on. You will hear soon. G.’ That was in

yesterday’s paper, and there is nothing in to-day’s. It’s all very

appropriate to Mrs. Warren’s lodger. If we wait a little, Watson, I don’t doubt

that the affair will grow more intelligible.” “Ah! there lies our problem. There is one rather obvious

line of investigation.” He took down the great book in which, day by day, he filed

the agony columns of the various London journals. “Dear me!” said he, turning

over the pages, “what a chorus of groans, cries, and bleatings! What a rag-bag of

singular happenings! But surely the most valuable hunting-ground that ever was given to a

student of the unusual! This person is alone and cannot be approached by letter without a

breach of that absolute secrecy which is desired. How is any news or any message to reach

him from without? Obviously by advertisement through a newspaper. There seems no other

way, and fortunately we need concern ourselves with the one paper only. Here are the Daily

Gazette extracts of the last fortnight. ‘Lady with a black boa at Prince’s

Skating Club’–that we may pass. ‘Surely Jimmy will not break his

mother’s heart’– that appears to be irrelevant. ‘If the lady who

fainted in the Brixton bus’– she does not interest me. ‘Every day my heart

longs– –’ Bleat, Watson– unmitigated bleat! Ah, this is a little more

possible. Listen to this: ‘Be patient. Will find some sure means of communication.

Meanwhile, this column. G.’ That is two days after Mrs. Warren’s lodger arrived.

It sounds plausible, does it not? The mysterious one could understand English, even if he

could not print it. Let us see if we can pick up the trace again. Yes, here we are–

three days later. ‘Am making successful arrangements. Patience and prudence. The

clouds will pass. G.’ Nothing for a week after that. Then comes something much more

definite: ‘The path is clearing. If I find chance signal message remember code

agreed–one A, two B, and so on. You will hear soon. G.’ That was in

yesterday’s paper, and there is nothing in to-day’s. It’s all very

appropriate to Mrs. Warren’s lodger. If we wait a little, Watson, I don’t doubt

that the affair will grow more intelligible.”

So it proved; for in the morning I found my friend standing on

the hearthrug with his back to the fire and a smile of complete satisfaction upon his

face. So it proved; for in the morning I found my friend standing on

the hearthrug with his back to the fire and a smile of complete satisfaction upon his

face.

“How’s this, Watson?” he cried, picking up the

paper from the table. “ ‘High red house with white stone facings. Third floor.

Second window left. After dusk. G.’ That is definite enough. I think after breakfast

we must make a little reconnaissance of Mrs. Warren’s neighbourhood. Ah, Mrs. Warren!

what news do you bring us this morning?” “How’s this, Watson?” he cried, picking up the

paper from the table. “ ‘High red house with white stone facings. Third floor.

Second window left. After dusk. G.’ That is definite enough. I think after breakfast

we must make a little reconnaissance of Mrs. Warren’s neighbourhood. Ah, Mrs. Warren!

what news do you bring us this morning?”

[905] Our

client had suddenly burst into the room with an explosive energy which told of some new

and momentous development. [905] Our

client had suddenly burst into the room with an explosive energy which told of some new

and momentous development.

“It’s a police matter, Mr. Holmes!” she cried.

“I’ll have no more of it! He shall pack out of there with his baggage. I would

have gone straight up and told him so, only I thought it was but fair to you to take your

opinion first. But I’m at the end of my patience, and when it comes to knocking my

old man about– –” “It’s a police matter, Mr. Holmes!” she cried.

“I’ll have no more of it! He shall pack out of there with his baggage. I would

have gone straight up and told him so, only I thought it was but fair to you to take your

opinion first. But I’m at the end of my patience, and when it comes to knocking my

old man about– –”

“Knocking Mr. Warren about?” “Knocking Mr. Warren about?”

“Using him roughly, anyway.” “Using him roughly, anyway.”

“But who used him roughly?” “But who used him roughly?”

“Ah! that’s what we want to know! It was this

morning, sir. Mr. Warren is a timekeeper at Morton and Waylight’s, in Tottenham Court

Road. He has to be out of the house before seven. Well, this morning he had not gone ten

paces down the road when two men came up behind him, threw a coat over his head, and

bundled him into a cab that was beside the curb. They drove him an hour, and then opened

the door and shot him out. He lay in the roadway so shaken in his wits that he never saw

what became of the cab. When he picked himself up he found he was on Hampstead Heath; so

he took a bus home, and there he lies now on the sofa, while I came straight round to tell

you what had happened.” “Ah! that’s what we want to know! It was this

morning, sir. Mr. Warren is a timekeeper at Morton and Waylight’s, in Tottenham Court

Road. He has to be out of the house before seven. Well, this morning he had not gone ten

paces down the road when two men came up behind him, threw a coat over his head, and

bundled him into a cab that was beside the curb. They drove him an hour, and then opened

the door and shot him out. He lay in the roadway so shaken in his wits that he never saw

what became of the cab. When he picked himself up he found he was on Hampstead Heath; so

he took a bus home, and there he lies now on the sofa, while I came straight round to tell

you what had happened.”

“Most interesting,” said Holmes. “Did he

observe the appearance of these men–did he hear them talk?” “Most interesting,” said Holmes. “Did he

observe the appearance of these men–did he hear them talk?”

“No; he is clean dazed. He just knows that he was lifted

up as if by magic and dropped as if by magic. Two at least were in it, and maybe

three.” “No; he is clean dazed. He just knows that he was lifted

up as if by magic and dropped as if by magic. Two at least were in it, and maybe

three.”

“And you connect this attack with your lodger?” “And you connect this attack with your lodger?”

“Well, we’ve lived there fifteen years and no such

happenings ever came before. I’ve had enough of him. Money’s not everything.

I’ll have him out of my house before the day is done.” “Well, we’ve lived there fifteen years and no such

happenings ever came before. I’ve had enough of him. Money’s not everything.

I’ll have him out of my house before the day is done.”

“Wait a bit, Mrs. Warren. Do nothing rash. I begin to

think that this affair may be very much more important than appeared at first sight. It is

clear now that some danger is threatening your lodger. It is equally clear that his

enemies, lying in wait for him near your door, mistook your husband for him in the foggy

morning light. On discovering their mistake they released him. What they would have done

had it not been a mistake, we can only conjecture.” “Wait a bit, Mrs. Warren. Do nothing rash. I begin to

think that this affair may be very much more important than appeared at first sight. It is

clear now that some danger is threatening your lodger. It is equally clear that his

enemies, lying in wait for him near your door, mistook your husband for him in the foggy

morning light. On discovering their mistake they released him. What they would have done

had it not been a mistake, we can only conjecture.”

“Well, what am I to do, Mr. Holmes?” “Well, what am I to do, Mr. Holmes?”

“I have a great fancy to see this lodger of yours, Mrs.

Warren.” “I have a great fancy to see this lodger of yours, Mrs.

Warren.”

“I don’t see how that is to be managed, unless you

break in the door. I always hear him unlock it as I go down the stair after I leave the

tray.” “I don’t see how that is to be managed, unless you

break in the door. I always hear him unlock it as I go down the stair after I leave the

tray.”

“He has to take the tray in. Surely we could conceal

ourselves and see him do it.” “He has to take the tray in. Surely we could conceal

ourselves and see him do it.”

The landlady thought for a moment. The landlady thought for a moment.

“Well, sir, there’s the box-room opposite. I could

arrange a looking-glass, maybe, and if you were behind the door– –” “Well, sir, there’s the box-room opposite. I could

arrange a looking-glass, maybe, and if you were behind the door– –”

“Excellent!” said Holmes. “When does he

lunch?” “Excellent!” said Holmes. “When does he

lunch?”

“About one, sir.” “About one, sir.”

“Then Dr. Watson and I will come round in time. For the

present, Mrs. Warren, good-bye.” “Then Dr. Watson and I will come round in time. For the

present, Mrs. Warren, good-bye.”

At half-past twelve we found ourselves upon the steps of Mrs.

Warren’s house–a high, thin, yellow-brick edifice in Great Orme Street, a narrow

thoroughfare at the northeast side of the British Museum. Standing as it does near the

corner of the street, it commands a view down Howe Street, with its more pretentious [906] houses. Holmes pointed with

a chuckle to one of these, a row of residential flats, which projected so that they could

not fail to catch the eye. At half-past twelve we found ourselves upon the steps of Mrs.

Warren’s house–a high, thin, yellow-brick edifice in Great Orme Street, a narrow

thoroughfare at the northeast side of the British Museum. Standing as it does near the

corner of the street, it commands a view down Howe Street, with its more pretentious [906] houses. Holmes pointed with

a chuckle to one of these, a row of residential flats, which projected so that they could

not fail to catch the eye.

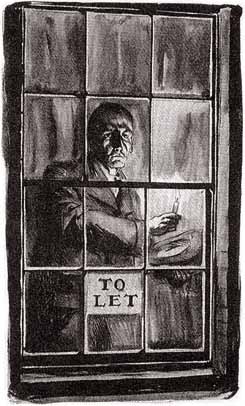

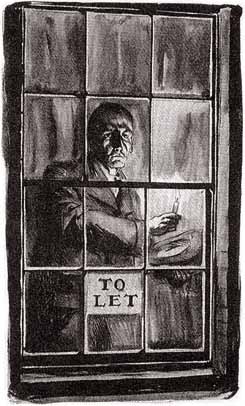

“See, Watson!” said he. “ ‘High red house

with stone facings.’ There is the signal station all right. We know the place, and we

know the code; so surely our task should be simple. There’s a ‘to let’ card

in that window. It is evidently an empty flat to which the confederate has access. Well,

Mrs. Warren, what now?” “See, Watson!” said he. “ ‘High red house

with stone facings.’ There is the signal station all right. We know the place, and we

know the code; so surely our task should be simple. There’s a ‘to let’ card

in that window. It is evidently an empty flat to which the confederate has access. Well,

Mrs. Warren, what now?”

“I have it all ready for you. If you will both come up

and leave your boots below on the landing, I’ll put you there now.” “I have it all ready for you. If you will both come up

and leave your boots below on the landing, I’ll put you there now.”

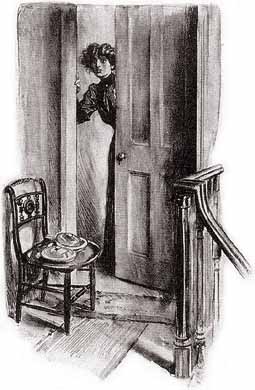

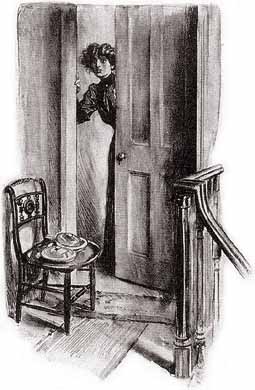

It was an excellent hiding-place which she had arranged. The

mirror was so placed that, seated in the dark, we could very plainly see the door

opposite. We had hardly settled down in it, and Mrs. Warren left us, when a distant tinkle

announced that our mysterious neighbour had rung. Presently the landlady appeared with the

tray, laid it down upon a chair beside the closed door, and then, treading heavily,

departed. Crouching together in the angle of the door, we kept our eyes fixed upon the

mirror. Suddenly, as the landlady’s footsteps died away, there was the creak of a

turning key, the handle revolved, and two thin hands darted out and lifted the tray from

the chair. An instant later it was hurriedly replaced, and I caught a glimpse of a dark,

beautiful, horrified face glaring at the narrow opening of the box-room. Then the door

crashed to, the key turned once more, and all was silence. Holmes twitched my sleeve, and

together we stole down the stair. It was an excellent hiding-place which she had arranged. The

mirror was so placed that, seated in the dark, we could very plainly see the door

opposite. We had hardly settled down in it, and Mrs. Warren left us, when a distant tinkle

announced that our mysterious neighbour had rung. Presently the landlady appeared with the

tray, laid it down upon a chair beside the closed door, and then, treading heavily,

departed. Crouching together in the angle of the door, we kept our eyes fixed upon the

mirror. Suddenly, as the landlady’s footsteps died away, there was the creak of a

turning key, the handle revolved, and two thin hands darted out and lifted the tray from

the chair. An instant later it was hurriedly replaced, and I caught a glimpse of a dark,

beautiful, horrified face glaring at the narrow opening of the box-room. Then the door

crashed to, the key turned once more, and all was silence. Holmes twitched my sleeve, and

together we stole down the stair.

“I will call again in the evening,” said he to

the expectant landlady. “I think, Watson, we can discuss this business better in our

own quarters.” “I will call again in the evening,” said he to

the expectant landlady. “I think, Watson, we can discuss this business better in our

own quarters.”

“My surmise, as you saw, proved to be correct,” said

he, speaking from the depths of his easy-chair. “There has been a substitution of

lodgers. What I did not foresee is that we should find a woman, and no ordinary woman,

Watson.” “My surmise, as you saw, proved to be correct,” said

he, speaking from the depths of his easy-chair. “There has been a substitution of

lodgers. What I did not foresee is that we should find a woman, and no ordinary woman,

Watson.”

“She saw us.” “She saw us.”

“Well, she saw something to alarm her. That is certain.

The general sequence of events is pretty clear, is it not? A couple seek refuge in London

from a very terrible and instant danger. The measure of that danger is the rigour of their

precautions. The man, who has some work which he must do, desires to leave the woman in

absolute safety while he does it. It is not an easy problem, but he solved it in an

original fashion, and so effectively that her presence was not even known to the landlady

who supplies her with food. The printed messages, as is now evident, were to prevent her

sex being discovered by her writing. The man cannot come near the woman, or he will guide

their enemies to her. Since he cannot communicate with her direct, he has recourse to the

agony column of a paper. So far all is clear.” “Well, she saw something to alarm her. That is certain.

The general sequence of events is pretty clear, is it not? A couple seek refuge in London

from a very terrible and instant danger. The measure of that danger is the rigour of their

precautions. The man, who has some work which he must do, desires to leave the woman in

absolute safety while he does it. It is not an easy problem, but he solved it in an

original fashion, and so effectively that her presence was not even known to the landlady

who supplies her with food. The printed messages, as is now evident, were to prevent her

sex being discovered by her writing. The man cannot come near the woman, or he will guide

their enemies to her. Since he cannot communicate with her direct, he has recourse to the

agony column of a paper. So far all is clear.”

“But what is at the root of it?” “But what is at the root of it?”

“Ah, yes, Watson–severely practical, as usual! What

is at the root of it all? Mrs. Warren’s whimsical problem enlarges somewhat and

assumes a more sinister aspect as we proceed. This much we can say: that it is no ordinary

love escapade. You saw the woman’s face at the sign of danger. We have heard, too, of

the attack upon the landlord, which was undoubtedly meant for the lodger. These alarms,

and the desperate need for secrecy, argue that the matter is one of life or death. The

attack upon Mr. Warren further shows that the enemy, whoever they are, are themselves not

aware of the substitution of the female lodger for the male. It is very curious and

complex, Watson.” “Ah, yes, Watson–severely practical, as usual! What

is at the root of it all? Mrs. Warren’s whimsical problem enlarges somewhat and

assumes a more sinister aspect as we proceed. This much we can say: that it is no ordinary

love escapade. You saw the woman’s face at the sign of danger. We have heard, too, of

the attack upon the landlord, which was undoubtedly meant for the lodger. These alarms,

and the desperate need for secrecy, argue that the matter is one of life or death. The

attack upon Mr. Warren further shows that the enemy, whoever they are, are themselves not

aware of the substitution of the female lodger for the male. It is very curious and

complex, Watson.”

“Why should you go further in it? What have you to gain

from it?” “Why should you go further in it? What have you to gain

from it?”

[907] “What,

indeed? It is art for art’s sake, Watson. I suppose when you doctored you found

yourself studying cases without thought of a fee?” [907] “What,

indeed? It is art for art’s sake, Watson. I suppose when you doctored you found

yourself studying cases without thought of a fee?”

“For my education, Holmes.” “For my education, Holmes.”

“Education never ends, Watson. It is a series of lessons

with the greatest for the last. This is an instructive case. There is neither money nor

credit in it, and yet one would wish to tidy it up. When dusk comes we should find

ourselves one stage advanced in our investigation.” “Education never ends, Watson. It is a series of lessons

with the greatest for the last. This is an instructive case. There is neither money nor

credit in it, and yet one would wish to tidy it up. When dusk comes we should find

ourselves one stage advanced in our investigation.”

When we returned to Mrs. Warren’s rooms, the gloom of a

London winter evening had thickened into one gray curtain, a dead monotone of colour,

broken only by the sharp yellow squares of the windows and the blurred haloes of the

gas-lamps. As we peered from the darkened sitting-room of the lodging-house, one more dim

light glimmered high up through the obscurity. When we returned to Mrs. Warren’s rooms, the gloom of a

London winter evening had thickened into one gray curtain, a dead monotone of colour,

broken only by the sharp yellow squares of the windows and the blurred haloes of the

gas-lamps. As we peered from the darkened sitting-room of the lodging-house, one more dim

light glimmered high up through the obscurity.

“Someone is moving in that room,” said Holmes in a

whisper, his gaunt and eager face thrust forward to the window-pane. “Yes, I can see

his shadow. There he is again! He has a candle in his hand. Now he is peering across. He

wants to be sure that she is on the lookout. Now he begins to flash. Take the message

also, Watson, that we may check each other. A single flash–that is A,

surely. Now, then. How many did you make it? Twenty. So did I. That should mean T.

AT–that’s intelligible enough! Another T. Surely

this is the beginning of a second word. Now, then–TENTA. Dead stop.

That can’t be all, Watson? ATTENTA gives no sense. Nor is it any

better as three words AT, TEN, TA, unless T.

A. are a person’s initials. There it goes again! What’s that? ATTE–why,

it is the same message over again. Curious, Watson, very curious! Now he is off once more!

AT–why, he is repeating it for the third time. ATTENTA three

times! How often will he repeat it? No, that seems to be the finish. He has withdrawn from

the window. What do you make of it, Watson?” “Someone is moving in that room,” said Holmes in a

whisper, his gaunt and eager face thrust forward to the window-pane. “Yes, I can see

his shadow. There he is again! He has a candle in his hand. Now he is peering across. He

wants to be sure that she is on the lookout. Now he begins to flash. Take the message

also, Watson, that we may check each other. A single flash–that is A,

surely. Now, then. How many did you make it? Twenty. So did I. That should mean T.

AT–that’s intelligible enough! Another T. Surely

this is the beginning of a second word. Now, then–TENTA. Dead stop.

That can’t be all, Watson? ATTENTA gives no sense. Nor is it any

better as three words AT, TEN, TA, unless T.

A. are a person’s initials. There it goes again! What’s that? ATTE–why,

it is the same message over again. Curious, Watson, very curious! Now he is off once more!

AT–why, he is repeating it for the third time. ATTENTA three

times! How often will he repeat it? No, that seems to be the finish. He has withdrawn from

the window. What do you make of it, Watson?”

“A cipher message, Holmes.” “A cipher message, Holmes.”

My companion gave a sudden chuckle of comprehension. “And

not a very obscure cipher, Watson,” said he. “Why, of course, it is Italian! The

A means that it is addressed to a woman. ‘Beware! Beware! Beware!’ How’s

that, Watson?” My companion gave a sudden chuckle of comprehension. “And

not a very obscure cipher, Watson,” said he. “Why, of course, it is Italian! The

A means that it is addressed to a woman. ‘Beware! Beware! Beware!’ How’s

that, Watson?”

“I believe you have hit it.” “I believe you have hit it.”

“Not a doubt of it. It is a very urgent message, thrice

repeated to make it more so. But beware of what? Wait a bit; he is coming to the window

once more.” “Not a doubt of it. It is a very urgent message, thrice

repeated to make it more so. But beware of what? Wait a bit; he is coming to the window

once more.”

Again we saw the dim silhouette of a crouching man and the

whisk of the small flame across the window as the signals were renewed. They came more

rapidly than before–so rapid that it was hard to follow them. Again we saw the dim silhouette of a crouching man and the

whisk of the small flame across the window as the signals were renewed. They came more

rapidly than before–so rapid that it was hard to follow them.

“PERICOLO–pericolo–eh,

what’s that, Watson? ‘Danger,’ isn’t it? Yes, by Jove, it’s a

danger signal. There he goes again! PERI. Halloa, what on earth–

–” “PERICOLO–pericolo–eh,

what’s that, Watson? ‘Danger,’ isn’t it? Yes, by Jove, it’s a

danger signal. There he goes again! PERI. Halloa, what on earth–

–”

The light had suddenly gone out, the glimmering square of

window had disappeared, and the third floor formed a dark band round the lofty building,

with its tiers of shining casements. That last warning cry had been suddenly cut short.

How, and by whom? The same thought occurred on the instant to us both. Holmes sprang up

from where he crouched by the window. The light had suddenly gone out, the glimmering square of

window had disappeared, and the third floor formed a dark band round the lofty building,

with its tiers of shining casements. That last warning cry had been suddenly cut short.

How, and by whom? The same thought occurred on the instant to us both. Holmes sprang up

from where he crouched by the window.

“This is serious, Watson,” he cried. “There is

some devilry going forward! Why should such a message stop in such a way? I should put

Scotland Yard in touch with this business–and yet, it is too pressing for us to

leave.” “This is serious, Watson,” he cried. “There is

some devilry going forward! Why should such a message stop in such a way? I should put

Scotland Yard in touch with this business–and yet, it is too pressing for us to

leave.”

“Shall I go for the police?” “Shall I go for the police?”

“We must define the situation a little more clearly. It

may bear some more innocent interpretation. Come, Watson, let us go across ourselves and

see what we can make of it.” “We must define the situation a little more clearly. It

may bear some more innocent interpretation. Come, Watson, let us go across ourselves and

see what we can make of it.”

2

[908] As

we walked rapidly down Howe Street I glanced back at the building which we had left.

There, dimly outlined at the top window, I could see the shadow of a head, a woman’s

head, gazing tensely, rigidly, out into the night, waiting with breathless suspense for

the renewal of that interrupted message. At the doorway of the Howe Street flats a man,

muffled in a cravat and greatcoat, was leaning against the railing. He started as the

hall-light fell upon our faces. [908] As

we walked rapidly down Howe Street I glanced back at the building which we had left.

There, dimly outlined at the top window, I could see the shadow of a head, a woman’s

head, gazing tensely, rigidly, out into the night, waiting with breathless suspense for

the renewal of that interrupted message. At the doorway of the Howe Street flats a man,

muffled in a cravat and greatcoat, was leaning against the railing. He started as the

hall-light fell upon our faces.

“Holmes!” he cried. “Holmes!” he cried.

“Why, Gregson!” said my companion as he shook hands

with the Scotland Yard detective. “Journeys end with lovers’ meetings. What

brings you here?” “Why, Gregson!” said my companion as he shook hands

with the Scotland Yard detective. “Journeys end with lovers’ meetings. What

brings you here?”

“The same reasons that bring you, I expect,” said

Gregson. “How you got on to it I can’t imagine.” “The same reasons that bring you, I expect,” said

Gregson. “How you got on to it I can’t imagine.”

“Different threads, but leading up to the same tangle.

I’ve been taking the signals.” “Different threads, but leading up to the same tangle.

I’ve been taking the signals.”

“Signals?” “Signals?”

“Yes, from that window. They broke off in the middle. We

came over to see the reason. But since it is safe in your hands I see no object in

continuing the business.” “Yes, from that window. They broke off in the middle. We

came over to see the reason. But since it is safe in your hands I see no object in

continuing the business.”

“Wait a bit!” cried Gregson eagerly. “I’ll

do you this justice, Mr. Holmes, that I was never in a case yet that I didn’t feel

stronger for having you on my side. There’s only the one exit to these flats, so we

have him safe.” “Wait a bit!” cried Gregson eagerly. “I’ll

do you this justice, Mr. Holmes, that I was never in a case yet that I didn’t feel

stronger for having you on my side. There’s only the one exit to these flats, so we

have him safe.”

“Who is he?” “Who is he?”

“Well, well, we score over you for once, Mr. Holmes. You

must give us best this time.” He struck his stick sharply upon the ground, on which a

cabman, his whip in his hand, sauntered over from a four-wheeler which stood on the far

side of the street. “May I introduce you to Mr. Sherlock Holmes?” he said to the

cabman. “This is Mr. Leverton, of Pinkerton’s American Agency.” “Well, well, we score over you for once, Mr. Holmes. You

must give us best this time.” He struck his stick sharply upon the ground, on which a

cabman, his whip in his hand, sauntered over from a four-wheeler which stood on the far

side of the street. “May I introduce you to Mr. Sherlock Holmes?” he said to the

cabman. “This is Mr. Leverton, of Pinkerton’s American Agency.”

“The hero of the Long Island cave mystery?” said

Holmes. “Sir, I am pleased to meet you.” “The hero of the Long Island cave mystery?” said

Holmes. “Sir, I am pleased to meet you.”

The American, a quiet, businesslike young man, with a

clean-shaven, hatchet face, flushed up at the words of commendation. “I am on the

trail of my life now, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “If I can get Gorgiano–

–” The American, a quiet, businesslike young man, with a

clean-shaven, hatchet face, flushed up at the words of commendation. “I am on the

trail of my life now, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “If I can get Gorgiano–

–”

“What! Gorgiano of the Red Circle?” “What! Gorgiano of the Red Circle?”

“Oh, he has a European fame, has he? Well, we’ve

learned all about him in America. We know he is at the bottom of fifty murders,

and yet we have nothing positive we can take him on. I tracked him over from New York, and

I’ve been close to him for a week in London, waiting some excuse to get my hand on

his collar. Mr. Gregson and I ran him to ground in that big tenement house, and

there’s only the one door, so he can’t slip us. There’s three folk come out

since he went in, but I’ll swear he wasn’t one of them.” “Oh, he has a European fame, has he? Well, we’ve

learned all about him in America. We know he is at the bottom of fifty murders,

and yet we have nothing positive we can take him on. I tracked him over from New York, and

I’ve been close to him for a week in London, waiting some excuse to get my hand on

his collar. Mr. Gregson and I ran him to ground in that big tenement house, and

there’s only the one door, so he can’t slip us. There’s three folk come out

since he went in, but I’ll swear he wasn’t one of them.”

“Mr. Holmes talks of signals,” said Gregson. “I

expect, as usual, he knows a good deal that we don’t.” “Mr. Holmes talks of signals,” said Gregson. “I

expect, as usual, he knows a good deal that we don’t.”

In a few clear words Holmes explained the situation as it had

appeared to us. The American struck his hands together with vexation. In a few clear words Holmes explained the situation as it had

appeared to us. The American struck his hands together with vexation.

“He’s on to us!” he cried. “He’s on to us!” he cried.

“Why do you think so?” “Why do you think so?”

“Well, it figures out that way, does it not? Here he is,

sending out messages to an accomplice–there are several of his gang in London. Then

suddenly, just as by [909] your

own account he was telling them that there was danger, he broke short off. What could it

mean except that from the window he had suddenly either caught sight of us in the street,

or in some way come to understand how close the danger was, and that he must act right

away if he was to avoid it? What do you suggest, Mr. Holmes?” “Well, it figures out that way, does it not? Here he is,

sending out messages to an accomplice–there are several of his gang in London. Then

suddenly, just as by [909] your

own account he was telling them that there was danger, he broke short off. What could it

mean except that from the window he had suddenly either caught sight of us in the street,

or in some way come to understand how close the danger was, and that he must act right

away if he was to avoid it? What do you suggest, Mr. Holmes?”

“That we go up at once and see for ourselves.” “That we go up at once and see for ourselves.”

“But we have no warrant for his arrest.” “But we have no warrant for his arrest.”

“He is in unoccupied premises under suspicious

circumstances,” said Gregson. “That is good enough for the moment. When we have

him by the heels we can see if New York can’t help us to keep him. I’ll take the

responsibility of arresting him now.” “He is in unoccupied premises under suspicious

circumstances,” said Gregson. “That is good enough for the moment. When we have

him by the heels we can see if New York can’t help us to keep him. I’ll take the

responsibility of arresting him now.”

Our official detectives may blunder in the matter of

intelligence, but never in that of courage. Gregson climbed the stair to arrest this

desperate murderer with the same absolutely quiet and businesslike bearing with which he

would have ascended the official staircase of Scotland Yard. The Pinkerton man had tried

to push past him, but Gregson had firmly elbowed him back. London dangers were the

privilege of the London force. Our official detectives may blunder in the matter of

intelligence, but never in that of courage. Gregson climbed the stair to arrest this

desperate murderer with the same absolutely quiet and businesslike bearing with which he

would have ascended the official staircase of Scotland Yard. The Pinkerton man had tried

to push past him, but Gregson had firmly elbowed him back. London dangers were the

privilege of the London force.

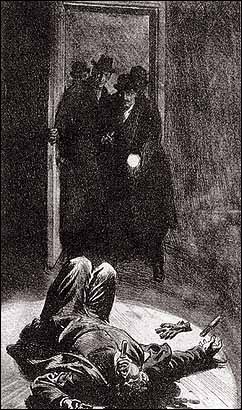

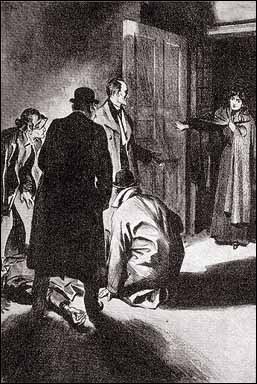

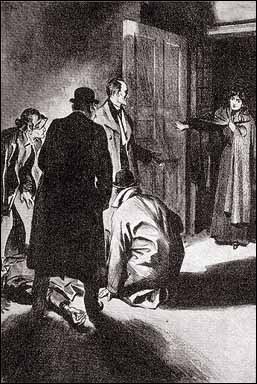

The door of the left-hand flat upon the third landing was

standing ajar. Gregson pushed it open. Within all was absolute silence and darkness. I

struck a match and lit the detective’s lantern. As I did so, and as the flicker

steadied into a flame, we all gave a gasp of surprise. On the deal boards of the

carpetless floor there was outlined a fresh track of blood. The red steps pointed towards

us and led away from an inner room, the door of which was closed. Gregson flung it open

and held his light full blaze in front of him, while we all peered eagerly over his

shoulders. The door of the left-hand flat upon the third landing was

standing ajar. Gregson pushed it open. Within all was absolute silence and darkness. I

struck a match and lit the detective’s lantern. As I did so, and as the flicker

steadied into a flame, we all gave a gasp of surprise. On the deal boards of the

carpetless floor there was outlined a fresh track of blood. The red steps pointed towards

us and led away from an inner room, the door of which was closed. Gregson flung it open

and held his light full blaze in front of him, while we all peered eagerly over his

shoulders.

In the middle of the floor of the empty room was huddled the

figure of an enormous man, his clean-shaven, swarthy face grotesquely horrible in its

contortion and his head encircled by a ghastly crimson halo of blood, lying in a broad wet

circle upon the white woodwork. His knees were drawn up, his hands thrown out in agony,

and from the centre of his broad, brown, upturned throat there projected the white haft of

a knife driven blade-deep into his body. Giant as he was, the man must have gone down like

a pole-axed ox before that terrific blow. Beside his right hand a most formidable

horn-handled, two-edged dagger lay upon the floor, and near it a black kid glove. In the middle of the floor of the empty room was huddled the

figure of an enormous man, his clean-shaven, swarthy face grotesquely horrible in its

contortion and his head encircled by a ghastly crimson halo of blood, lying in a broad wet

circle upon the white woodwork. His knees were drawn up, his hands thrown out in agony,

and from the centre of his broad, brown, upturned throat there projected the white haft of

a knife driven blade-deep into his body. Giant as he was, the man must have gone down like

a pole-axed ox before that terrific blow. Beside his right hand a most formidable

horn-handled, two-edged dagger lay upon the floor, and near it a black kid glove.

“By George! it’s Black Gorgiano himself!”

cried the American detective. “Someone has got ahead of us this time.” “By George! it’s Black Gorgiano himself!”

cried the American detective. “Someone has got ahead of us this time.”

“Here is the candle in the window, Mr. Holmes,” said

Gregson. “Why, whatever are you doing?” “Here is the candle in the window, Mr. Holmes,” said

Gregson. “Why, whatever are you doing?”

Holmes had stepped across, had lit the candle, and was passing

it backward and forward across the window-panes. Then he peered into the darkness, blew

the candle out, and threw it on the floor. Holmes had stepped across, had lit the candle, and was passing

it backward and forward across the window-panes. Then he peered into the darkness, blew

the candle out, and threw it on the floor.

“I rather think that will be helpful,” said he.

He came over and stood in deep thought while the two professionals were examining the

body. “You say that three people came out from the flat while you were waiting

downstairs,” said he at last. “Did you observe them closely?” “I rather think that will be helpful,” said he.

He came over and stood in deep thought while the two professionals were examining the

body. “You say that three people came out from the flat while you were waiting

downstairs,” said he at last. “Did you observe them closely?”

“Yes, I did.” “Yes, I did.”

“Was there a fellow about thirty, black-bearded, dark, of

middle size?” “Was there a fellow about thirty, black-bearded, dark, of

middle size?”

“Yes; he was the last to pass me.” “Yes; he was the last to pass me.”

“That is your man, I fancy. I can give you his

description, and we have a very excellent outline of his footmark. That should be enough

for you.” “That is your man, I fancy. I can give you his

description, and we have a very excellent outline of his footmark. That should be enough

for you.”

[910] “Not

much, Mr. Holmes, among the millions of London.” [910] “Not

much, Mr. Holmes, among the millions of London.”

“Perhaps not. That is why I thought it best to summon

this lady to your aid.” “Perhaps not. That is why I thought it best to summon

this lady to your aid.”

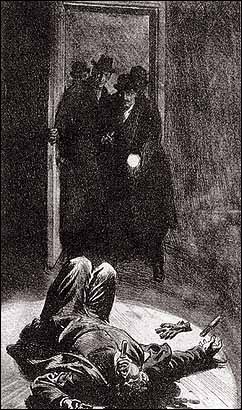

We all turned round at the words. There, framed in the

doorway, was a tall and beautiful woman–the mysterious lodger of Bloomsbury. Slowly

she advanced, her face pale and drawn with a frightful apprehension, her eyes fixed and

staring, her terrified gaze riveted upon the dark figure on the floor. We all turned round at the words. There, framed in the

doorway, was a tall and beautiful woman–the mysterious lodger of Bloomsbury. Slowly

she advanced, her face pale and drawn with a frightful apprehension, her eyes fixed and

staring, her terrified gaze riveted upon the dark figure on the floor.

“You have killed him!” she muttered. “Oh, Dio

mio, you have killed him!” Then I heard a sudden sharp intake of her breath, and

she sprang into the air with a cry of joy. Round and round the room she danced, her hands

clapping, her dark eyes gleaming with delighted wonder, and a thousand pretty Italian

exclamations pouring from her lips. It was terrible and amazing to see such a woman so

convulsed with joy at such a sight. Suddenly she stopped and gazed at us all with a

questioning stare. “You have killed him!” she muttered. “Oh, Dio

mio, you have killed him!” Then I heard a sudden sharp intake of her breath, and

she sprang into the air with a cry of joy. Round and round the room she danced, her hands

clapping, her dark eyes gleaming with delighted wonder, and a thousand pretty Italian

exclamations pouring from her lips. It was terrible and amazing to see such a woman so

convulsed with joy at such a sight. Suddenly she stopped and gazed at us all with a

questioning stare.

“But you! You are police, are you not? You have killed

Giuseppe Gorgiano. Is it not so?” “But you! You are police, are you not? You have killed

Giuseppe Gorgiano. Is it not so?”

“We are police, madam.” “We are police, madam.”

She looked round into the shadows of the room. She looked round into the shadows of the room.

“But where, then, is Gennaro?” she asked. “He

is my husband, Gennaro Lucca. I am Emilia Lucca, and we are both from New York. Where is

Gennaro? He called me this moment from this window, and I ran with all my speed.” “But where, then, is Gennaro?” she asked. “He

is my husband, Gennaro Lucca. I am Emilia Lucca, and we are both from New York. Where is

Gennaro? He called me this moment from this window, and I ran with all my speed.”

“It was I who called,” said Holmes. “It was I who called,” said Holmes.

“You! How could you call?” “You! How could you call?”

“Your cipher was not difficult, madam. Your presence here

was desirable. I knew that I had only to flash ‘Vieni’ and you would

surely come.” “Your cipher was not difficult, madam. Your presence here

was desirable. I knew that I had only to flash ‘Vieni’ and you would

surely come.”

The beautiful Italian looked with awe at my companion. The beautiful Italian looked with awe at my companion.

“I do not understand how you know these things,” she

said. “Giuseppe Gorgiano–how did he– –” She paused, and then

suddenly her face lit up with pride and delight. “Now I see it! My Gennaro! My

splendid, beautiful Gennaro, who has guarded me safe from all harm, he did it, with his

own strong hand he killed the monster! Oh, Gennaro, how wonderful you are! What woman

could ever be worthy of such a man?” “I do not understand how you know these things,” she

said. “Giuseppe Gorgiano–how did he– –” She paused, and then

suddenly her face lit up with pride and delight. “Now I see it! My Gennaro! My

splendid, beautiful Gennaro, who has guarded me safe from all harm, he did it, with his

own strong hand he killed the monster! Oh, Gennaro, how wonderful you are! What woman

could ever be worthy of such a man?”

“Well, Mrs. Lucca,” said the prosaic Gregson, laying

his hand upon the lady’s sleeve with as little sentiment as if she were a Notting

Hill hooligan, “I am not very clear yet who you are or what you are; but you’ve

said enough to make it very clear that we shall want you at the Yard.” “Well, Mrs. Lucca,” said the prosaic Gregson, laying

his hand upon the lady’s sleeve with as little sentiment as if she were a Notting

Hill hooligan, “I am not very clear yet who you are or what you are; but you’ve

said enough to make it very clear that we shall want you at the Yard.”

“One moment, Gregson,” said Holmes. “I rather

fancy that this lady may be as anxious to give us information as we can be to get it. You

understand, madam, that your husband will be arrested and tried for the death of the man

who lies before us? What you say may be used in evidence. But if you think that he has

acted from motives which are not criminal, and which he would wish to have known, then you

cannot serve him better than by telling us the whole story.” “One moment, Gregson,” said Holmes. “I rather

fancy that this lady may be as anxious to give us information as we can be to get it. You

understand, madam, that your husband will be arrested and tried for the death of the man

who lies before us? What you say may be used in evidence. But if you think that he has

acted from motives which are not criminal, and which he would wish to have known, then you

cannot serve him better than by telling us the whole story.”

“Now that Gorgiano is dead we fear nothing,” said

the lady. “He was a devil and a monster, and there can be no judge in the world who

would punish my husband for having killed him.” “Now that Gorgiano is dead we fear nothing,” said

the lady. “He was a devil and a monster, and there can be no judge in the world who

would punish my husband for having killed him.”

“In that case,” said Holmes, “my suggestion is

that we lock this door, leave things as we found them, go with this lady to her room, and

form our opinion after we have heard what it is that she has to say to us.” “In that case,” said Holmes, “my suggestion is

that we lock this door, leave things as we found them, go with this lady to her room, and

form our opinion after we have heard what it is that she has to say to us.”

Half an hour later we were seated, all four, in the small

sitting-room of Signora Lucca, listening to her remarkable narrative of those sinister

events, the ending of which we had chanced to witness. She spoke in rapid and fluent but

very [911] unconventional

English, which, for the sake of clearness, I will make grammatical. Half an hour later we were seated, all four, in the small

sitting-room of Signora Lucca, listening to her remarkable narrative of those sinister

events, the ending of which we had chanced to witness. She spoke in rapid and fluent but

very [911] unconventional

English, which, for the sake of clearness, I will make grammatical.

“I was born in Posilippo, near Naples,” said she,

“and was the daughter of Augusto Barelli, who was the chief lawyer and once the

deputy of that part. Gennaro was in my father’s employment, and I came to love him,

as any woman must. He had neither money nor position–nothing but his beauty and

strength and energy–so my father forbade the match. We fled together, were married at

Bari, and sold my jewels to gain the money which would take us to America. This was four

years ago, and we have been in New York ever since. “I was born in Posilippo, near Naples,” said she,

“and was the daughter of Augusto Barelli, who was the chief lawyer and once the

deputy of that part. Gennaro was in my father’s employment, and I came to love him,

as any woman must. He had neither money nor position–nothing but his beauty and

strength and energy–so my father forbade the match. We fled together, were married at

Bari, and sold my jewels to gain the money which would take us to America. This was four

years ago, and we have been in New York ever since.

“Fortune was very good to us at first. Gennaro was able

to do a service to an Italian gentleman–he saved him from some ruffians in the place

called the Bowery, and so made a powerful friend. His name was Tito Castalotte, and he was

the senior partner of the great firm of Castalotte and Zamba, who are the chief fruit

importers of New York. Signor Zamba is an invalid, and our new friend Castalotte has all

power within the firm, which employs more than three hundred men. He took my husband into

his employment, made him head of a department, and showed his good-will towards him in

every way. Signor Castalotte was a bachelor, and I believe that he felt as if Gennaro was

his son, and both my husband and I loved him as if he were our father. We had taken and

furnished a little house in Brooklyn, and our whole future seemed assured when that black

cloud appeared which was soon to overspread our sky. “Fortune was very good to us at first. Gennaro was able

to do a service to an Italian gentleman–he saved him from some ruffians in the place

called the Bowery, and so made a powerful friend. His name was Tito Castalotte, and he was

the senior partner of the great firm of Castalotte and Zamba, who are the chief fruit

importers of New York. Signor Zamba is an invalid, and our new friend Castalotte has all

power within the firm, which employs more than three hundred men. He took my husband into

his employment, made him head of a department, and showed his good-will towards him in

every way. Signor Castalotte was a bachelor, and I believe that he felt as if Gennaro was

his son, and both my husband and I loved him as if he were our father. We had taken and

furnished a little house in Brooklyn, and our whole future seemed assured when that black

cloud appeared which was soon to overspread our sky.

“One night, when Gennaro returned from his work, he

brought a fellow-countryman back with him. His name was Gorgiano, and he had come also

from Posilippo. He was a huge man, as you can testify, for you have looked upon his

corpse. Not only was his body that of a giant but everything about him was grotesque,

gigantic, and terrifying. His voice was like thunder in our little house. There was scarce

room for the whirl of his great arms as he talked. His thoughts, his emotions, his

passions, all were exaggerated and monstrous. He talked, or rather roared, with such

energy that others could but sit and listen, cowed with the mighty stream of words. His

eyes blazed at you and held you at his mercy. He was a terrible and wonderful man. I thank

God that he is dead! “One night, when Gennaro returned from his work, he

brought a fellow-countryman back with him. His name was Gorgiano, and he had come also

from Posilippo. He was a huge man, as you can testify, for you have looked upon his

corpse. Not only was his body that of a giant but everything about him was grotesque,

gigantic, and terrifying. His voice was like thunder in our little house. There was scarce

room for the whirl of his great arms as he talked. His thoughts, his emotions, his

passions, all were exaggerated and monstrous. He talked, or rather roared, with such

energy that others could but sit and listen, cowed with the mighty stream of words. His

eyes blazed at you and held you at his mercy. He was a terrible and wonderful man. I thank

God that he is dead!

“He came again and again. Yet I was aware that Gennaro

was no more happy than I was in his presence. My poor husband would sit pale and listless,

listening to the endless raving upon politics and upon social questions which made up our

visitor’s conversation. Gennaro said nothing, but I, who knew him so well, could read

in his face some emotion which I had never seen there before. At first I thought that it

was dislike. And then, gradually, I understood that it was more than dislike. It was

fear–a deep, secret, shrinking fear. That night–the night that I read his

terror–I put my arms round him and I implored him by his love for me and by all that

he held dear to hold nothing from me, and to tell me why this huge man overshadowed him

so. “He came again and again. Yet I was aware that Gennaro

was no more happy than I was in his presence. My poor husband would sit pale and listless,

listening to the endless raving upon politics and upon social questions which made up our

visitor’s conversation. Gennaro said nothing, but I, who knew him so well, could read

in his face some emotion which I had never seen there before. At first I thought that it

was dislike. And then, gradually, I understood that it was more than dislike. It was

fear–a deep, secret, shrinking fear. That night–the night that I read his

terror–I put my arms round him and I implored him by his love for me and by all that

he held dear to hold nothing from me, and to tell me why this huge man overshadowed him

so.

“He told me, and my own heart grew cold as ice as I

listened. My poor Gennaro, in his wild and fiery days, when all the world seemed against

him and his mind was driven half mad by the injustices of life, had joined a Neapolitan

society, the Red Circle, which was allied to the old Carbonari. The oaths and secrets of

this brotherhood were frightful, but once within its rule no escape was possible. When we

had fled to America Gennaro thought that he had cast it all off forever. What was his

horror one evening to meet in the streets the very man who had initiated him in Naples,

the giant Gorgiano, a man who had earned the name of ‘Death’ in the south of

Italy, for he was red to the elbow in murder! He had come to New [912] York to avoid the Italian police, and he had already

planted a branch of this dreadful society in his new home. All this Gennaro told me and

showed me a summons which he had received that very day, a Red Circle drawn upon the head

of it telling him that a lodge would be held upon a certain date, and that his presence at

it was required and ordered. “He told me, and my own heart grew cold as ice as I

listened. My poor Gennaro, in his wild and fiery days, when all the world seemed against

him and his mind was driven half mad by the injustices of life, had joined a Neapolitan

society, the Red Circle, which was allied to the old Carbonari. The oaths and secrets of

this brotherhood were frightful, but once within its rule no escape was possible. When we

had fled to America Gennaro thought that he had cast it all off forever. What was his

horror one evening to meet in the streets the very man who had initiated him in Naples,

the giant Gorgiano, a man who had earned the name of ‘Death’ in the south of

Italy, for he was red to the elbow in murder! He had come to New [912] York to avoid the Italian police, and he had already

planted a branch of this dreadful society in his new home. All this Gennaro told me and

showed me a summons which he had received that very day, a Red Circle drawn upon the head

of it telling him that a lodge would be held upon a certain date, and that his presence at

it was required and ordered.

“That was bad enough, but worse was to come. I had

noticed for some time that when Gorgiano came to us, as he constantly did, in the evening,

he spoke much to me; and even when his words were to my husband those terrible, glaring,

wild-beast eyes of his were always turned upon me. One night his secret came out. I had

awakened what he called ‘love’ within him–the love of a brute– a

savage. Gennaro had not yet returned when he came. He pushed his way in, seized me in his

mighty arms, hugged me in his bear’s embrace, covered me with kisses, and implored me

to come away with him. I was struggling and screaming when Gennaro entered and attacked

him. He struck Gennaro senseless and fled from the house which he was never more to enter.

It was a deadly enemy that we made that night. “That was bad enough, but worse was to come. I had

noticed for some time that when Gorgiano came to us, as he constantly did, in the evening,

he spoke much to me; and even when his words were to my husband those terrible, glaring,

wild-beast eyes of his were always turned upon me. One night his secret came out. I had

awakened what he called ‘love’ within him–the love of a brute– a

savage. Gennaro had not yet returned when he came. He pushed his way in, seized me in his

mighty arms, hugged me in his bear’s embrace, covered me with kisses, and implored me

to come away with him. I was struggling and screaming when Gennaro entered and attacked

him. He struck Gennaro senseless and fled from the house which he was never more to enter.

It was a deadly enemy that we made that night.

“A few days later came the meeting. Gennaro returned from

it with a face which told me that something dreadful had occurred. It was worse than we

could have imagined possible. The funds of the society were raised by blackmailing rich

Italians and threatening them with violence should they refuse the money. It seems that

Castalotte, our dear friend and benefactor, had been approached. He had refused to yield

to threats, and he had handed the notices to the police. It was resolved now that such an

example should be made of him as would prevent any other victim from rebelling. At the

meeting it was arranged that he and his house should be blown up with dynamite. There was

a drawing of lots as to who should carry out the deed. Gennaro saw our enemy’s cruel

face smiling at him as he dipped his hand in the bag. No doubt it had been prearranged in

some fashion, for it was the fatal disc with the Red Circle upon it, the mandate for

murder, which lay upon his palm. He was to kill his best friend, or he was to expose

himself and me to the vengeance of his comrades. It was part of their fiendish system to

punish those whom they feared or hated by injuring not only their own persons but those

whom they loved, and it was the knowledge of this which hung as a terror over my poor

Gennaro’s head and drove him nearly crazy with apprehension. “A few days later came the meeting. Gennaro returned from

it with a face which told me that something dreadful had occurred. It was worse than we

could have imagined possible. The funds of the society were raised by blackmailing rich

Italians and threatening them with violence should they refuse the money. It seems that

Castalotte, our dear friend and benefactor, had been approached. He had refused to yield

to threats, and he had handed the notices to the police. It was resolved now that such an

example should be made of him as would prevent any other victim from rebelling. At the

meeting it was arranged that he and his house should be blown up with dynamite. There was

a drawing of lots as to who should carry out the deed. Gennaro saw our enemy’s cruel

face smiling at him as he dipped his hand in the bag. No doubt it had been prearranged in

some fashion, for it was the fatal disc with the Red Circle upon it, the mandate for

murder, which lay upon his palm. He was to kill his best friend, or he was to expose

himself and me to the vengeance of his comrades. It was part of their fiendish system to

punish those whom they feared or hated by injuring not only their own persons but those

whom they loved, and it was the knowledge of this which hung as a terror over my poor

Gennaro’s head and drove him nearly crazy with apprehension.

“All that night we sat together, our arms round each

other, each strengthening each for the troubles that lay before us. The very next evening

had been fixed for the attempt. By midday my husband and I were on our way to London, but

not before he had given our benefactor full warning of his danger, and had also left such

information for the police as would safeguard his life for the future. “All that night we sat together, our arms round each

other, each strengthening each for the troubles that lay before us. The very next evening

had been fixed for the attempt. By midday my husband and I were on our way to London, but

not before he had given our benefactor full warning of his danger, and had also left such

information for the police as would safeguard his life for the future.

“The rest, gentlemen, you know for yourselves. We were

sure that our enemies would be behind us like our own shadows. Gorgiano had his private

reasons for vengeance, but in any case we knew how ruthless, cunning, and untiring he

could be. Both Italy and America are full of stories of his dreadful powers. If ever they

were exerted it would be now. My darling made use of the few clear days which our start

had given us in arranging for a refuge for me in such a fashion that no possible danger

could reach me. For his own part, he wished to be free that he might communicate both with

the American and with the Italian police. I do not myself know where he lived, or how. All

that I learned was through the columns of a newspaper. But once as I looked through my

window, I saw two Italians watching the house, and I understood that in some way Gorgiano

had found out our retreat. Finally Gennaro told me, through the paper, that he would

signal to [913] me from a

certain window, but when the signals came they were nothing but warnings, which were

suddenly interrupted. It is very clear to me now that he knew Gorgiano to be close upon

him, and that, thank God! he was ready for him when he came. And now, gentlemen, I would

ask you whether we have anything to fear from the law, or whether any judge upon earth

would condemn my Gennaro for what he has done?” “The rest, gentlemen, you know for yourselves. We were

sure that our enemies would be behind us like our own shadows. Gorgiano had his private

reasons for vengeance, but in any case we knew how ruthless, cunning, and untiring he

could be. Both Italy and America are full of stories of his dreadful powers. If ever they

were exerted it would be now. My darling made use of the few clear days which our start

had given us in arranging for a refuge for me in such a fashion that no possible danger

could reach me. For his own part, he wished to be free that he might communicate both with

the American and with the Italian police. I do not myself know where he lived, or how. All

that I learned was through the columns of a newspaper. But once as I looked through my

window, I saw two Italians watching the house, and I understood that in some way Gorgiano

had found out our retreat. Finally Gennaro told me, through the paper, that he would

signal to [913] me from a

certain window, but when the signals came they were nothing but warnings, which were

suddenly interrupted. It is very clear to me now that he knew Gorgiano to be close upon

him, and that, thank God! he was ready for him when he came. And now, gentlemen, I would

ask you whether we have anything to fear from the law, or whether any judge upon earth

would condemn my Gennaro for what he has done?”

“Well, Mr. Gregson,” said the American, looking

across at the official, “I don’t know what your British point of view may be,

but I guess that in New York this lady’s husband will receive a pretty general vote

of thanks.” “Well, Mr. Gregson,” said the American, looking

across at the official, “I don’t know what your British point of view may be,

but I guess that in New York this lady’s husband will receive a pretty general vote

of thanks.”

“She will have to come with me and see the chief,”

Gregson answered. “If what she says is corroborated, I do not think she or her

husband has much to fear. But what I can’t make head or tail of, Mr. Holmes, is how

on earth you got yourself mixed up in the matter.” “She will have to come with me and see the chief,”

Gregson answered. “If what she says is corroborated, I do not think she or her

husband has much to fear. But what I can’t make head or tail of, Mr. Holmes, is how

on earth you got yourself mixed up in the matter.”

“Education, Gregson, education. Still seeking knowledge

at the old university. Well, Watson, you have one more specimen of the tragic and

grotesque to add to your collection. By the way, it is not eight o’clock, and a

Wagner night at Covent Garden! If we hurry, we might be in time for the second act.” “Education, Gregson, education. Still seeking knowledge

at the old university. Well, Watson, you have one more specimen of the tragic and

grotesque to add to your collection. By the way, it is not eight o’clock, and a

Wagner night at Covent Garden! If we hurry, we might be in time for the second act.”

|

![]() But the landlady had the pertinacity and also the cunning of

her sex. She held her ground firmly.

But the landlady had the pertinacity and also the cunning of

her sex. She held her ground firmly.![]() “You arranged an affair for a lodger of mine last

year,” she said–“Mr. Fairdale Hobbs.”

“You arranged an affair for a lodger of mine last

year,” she said–“Mr. Fairdale Hobbs.”![]() “Ah, yes–a simple matter.”

“Ah, yes–a simple matter.”![]() “But he would never cease talking of it–your

kindness, sir, and the way in which you brought light into the darkness. I remembered his

words when I was in doubt and darkness myself. I know you could if you only would.”

“But he would never cease talking of it–your

kindness, sir, and the way in which you brought light into the darkness. I remembered his

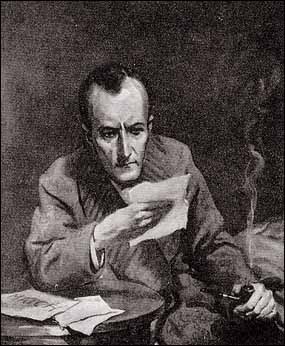

words when I was in doubt and darkness myself. I know you could if you only would.”![]() Holmes was accessible upon the side of flattery, and also, to

do him justice, upon the side of kindliness. The two forces made him lay down his

gum-brush with a sigh of resignation and push back his chair.

Holmes was accessible upon the side of flattery, and also, to

do him justice, upon the side of kindliness. The two forces made him lay down his

gum-brush with a sigh of resignation and push back his chair.![]() “Well, well, Mrs. Warren, let us hear about it, then. You

don’t object to tobacco, I take it? Thank you, Watson–the matches! You are

uneasy, as I understand, because your new lodger remains in his rooms and you cannot see

him. Why, bless you, Mrs. Warren, if I were your lodger you often would not see me for

weeks on end.”

“Well, well, Mrs. Warren, let us hear about it, then. You

don’t object to tobacco, I take it? Thank you, Watson–the matches! You are

uneasy, as I understand, because your new lodger remains in his rooms and you cannot see

him. Why, bless you, Mrs. Warren, if I were your lodger you often would not see me for

weeks on end.”![]() “No doubt, sir; but this is different. It frightens me,

Mr. Holmes. I can’t sleep for fright. To hear his quick step moving here and moving

there from early morning [902] to

late at night, and yet never to catch so much as a glimpse of him–it’s more than

I can stand. My husband is as nervous over it as I am, but he is out at his work all day,

while I get no rest from it. What is he hiding for? What has he done? Except for the girl,

I am all alone in the house with him, and it’s more than my nerves can stand.”

“No doubt, sir; but this is different. It frightens me,

Mr. Holmes. I can’t sleep for fright. To hear his quick step moving here and moving

there from early morning [902] to

late at night, and yet never to catch so much as a glimpse of him–it’s more than

I can stand. My husband is as nervous over it as I am, but he is out at his work all day,

while I get no rest from it. What is he hiding for? What has he done? Except for the girl,

I am all alone in the house with him, and it’s more than my nerves can stand.”![]() Holmes leaned forward and laid his long, thin fingers upon the

woman’s shoulder. He had an almost hypnotic power of soothing when he wished. The

scared look faded from her eyes, and her agitated features smoothed into their usual

commonplace. She sat down in the chair which he had indicated.

Holmes leaned forward and laid his long, thin fingers upon the

woman’s shoulder. He had an almost hypnotic power of soothing when he wished. The

scared look faded from her eyes, and her agitated features smoothed into their usual