Chapter 2

SHERLOCK HOLMES DISCOURSES

IT WAS one of those dramatic moments for which my friend existed. It

would be an overstatement to say that he was shocked or even excited by the amazing

announcement. Without having a tinge of cruelty in his singular composition, he was

undoubtedly callous from long overstimulation. Yet, if his emotions were dulled, his

intellectual perceptions were exceedingly active. There was no trace then of the horror

which I had myself felt at this curt declaration; but his face showed rather the quiet and

interested composure of the chemist who sees the crystals falling into position from his

oversaturated solution.

![]() “Remarkable!” said he. “Remarkable!”

“Remarkable!” said he. “Remarkable!”

![]() “You don’t seem surprised.”

“You don’t seem surprised.”

![]() “Interested, Mr. Mac, but hardly surprised. Why should I

be surprised? I receive an anonymous communication from a quarter which I know to be

important, warning me that danger threatens a certain person. Within an hour I learn that

this danger has actually materialized and that the person is dead. I am interested; but,

as you observe, I am not surprised.”

“Interested, Mr. Mac, but hardly surprised. Why should I

be surprised? I receive an anonymous communication from a quarter which I know to be

important, warning me that danger threatens a certain person. Within an hour I learn that

this danger has actually materialized and that the person is dead. I am interested; but,

as you observe, I am not surprised.”

![]() In a few short sentences he explained to the inspector the

facts about the letter and the cipher. MacDonald sat with his chin on his hands and his

great sandy eyebrows bunched into a yellow tangle.

In a few short sentences he explained to the inspector the

facts about the letter and the cipher. MacDonald sat with his chin on his hands and his

great sandy eyebrows bunched into a yellow tangle.

![]() “I was going down to Birlstone this morning,” said

he. “I had come to ask you if you cared to come with me–you and your friend

here. But from what you say we might perhaps be doing better work in London.”

“I was going down to Birlstone this morning,” said

he. “I had come to ask you if you cared to come with me–you and your friend

here. But from what you say we might perhaps be doing better work in London.”

![]() “I rather think not,” said Holmes.

“I rather think not,” said Holmes.

![]() [775] “Hang

it all, Mr. Holmes!” cried the inspector. “The papers will be full of the

Birlstone mystery in a day or two; but where’s the mystery if there is a man in

London who prophesied the crime before ever it occurred? We have only to lay our hands on

that man, and the rest will follow.”

[775] “Hang

it all, Mr. Holmes!” cried the inspector. “The papers will be full of the

Birlstone mystery in a day or two; but where’s the mystery if there is a man in

London who prophesied the crime before ever it occurred? We have only to lay our hands on

that man, and the rest will follow.”

![]() “No doubt, Mr. Mac. But how do you propose to lay your

hands on the so-called Porlock?”

“No doubt, Mr. Mac. But how do you propose to lay your

hands on the so-called Porlock?”

![]() MacDonald turned over the letter which Holmes had handed him.

“Posted in Camberwell–that doesn’t help us much. Name, you say, is assumed.

Not much to go on, certainly. Didn’t you say that you have sent him money?”

MacDonald turned over the letter which Holmes had handed him.

“Posted in Camberwell–that doesn’t help us much. Name, you say, is assumed.

Not much to go on, certainly. Didn’t you say that you have sent him money?”

![]() “Twice.”

“Twice.”

![]() “And how?”

“And how?”

![]() “In notes to Camberwell postoffice.”

“In notes to Camberwell postoffice.”

![]() “Did you ever trouble to see who called for them?”

“Did you ever trouble to see who called for them?”

![]() “No.”

“No.”

![]() The inspector looked surprised and a little shocked. “Why

not?”

The inspector looked surprised and a little shocked. “Why

not?”

![]() “Because I always keep faith. I had promised when he

first wrote that I would not try to trace him.”

“Because I always keep faith. I had promised when he

first wrote that I would not try to trace him.”

![]() “You think there is someone behind him?”

“You think there is someone behind him?”

![]() “I know there is.”

“I know there is.”

![]() “This professor that I’ve heard you mention?”

“This professor that I’ve heard you mention?”

![]() “Exactly!”

“Exactly!”

![]() Inspector MacDonald smiled, and his eyelid quivered as he

glanced towards me. “I won’t conceal from you, Mr. Holmes, that we think in the

C. I. D. that you have a wee bit of a bee in your bonnet over this professor. I made some

inquiries myself about the matter. He seems to be a very respectable, learned, and

talented sort of man.”

Inspector MacDonald smiled, and his eyelid quivered as he

glanced towards me. “I won’t conceal from you, Mr. Holmes, that we think in the

C. I. D. that you have a wee bit of a bee in your bonnet over this professor. I made some

inquiries myself about the matter. He seems to be a very respectable, learned, and

talented sort of man.”

![]() “I’m glad you’ve got so far as to recognize the

talent.”

“I’m glad you’ve got so far as to recognize the

talent.”

![]() “Man, you can’t but recognize it! After I heard your

view I made it my business to see him. I had a chat with him on eclipses. How the talk got

that way I canna think; but he had out a reflector lantern and a globe, and made it all

clear in a minute. He lent me a book; but I don’t mind saying that it was a bit above

my head, though I had a good Aberdeen upbringing. He’d have made a grand meenister

with his thin face and gray hair and solemn-like way of talking. When he put his hand on

my shoulder as we were parting, it was like a father’s blessing before you go out

into the cold, cruel world.”

“Man, you can’t but recognize it! After I heard your

view I made it my business to see him. I had a chat with him on eclipses. How the talk got

that way I canna think; but he had out a reflector lantern and a globe, and made it all

clear in a minute. He lent me a book; but I don’t mind saying that it was a bit above

my head, though I had a good Aberdeen upbringing. He’d have made a grand meenister

with his thin face and gray hair and solemn-like way of talking. When he put his hand on

my shoulder as we were parting, it was like a father’s blessing before you go out

into the cold, cruel world.”

![]() Holmes chuckled and rubbed his hands. “Great!” he

said. “Great! Tell me, Friend MacDonald, this pleasing and touching interview was, I

suppose, in the professor’s study?”

Holmes chuckled and rubbed his hands. “Great!” he

said. “Great! Tell me, Friend MacDonald, this pleasing and touching interview was, I

suppose, in the professor’s study?”

![]() “That’s so.”

“That’s so.”

![]() “A fine room, is it not?”

“A fine room, is it not?”

![]() “Very fine–very handsome indeed, Mr. Holmes.”

“Very fine–very handsome indeed, Mr. Holmes.”

![]() “You sat in front of his writing desk?”

“You sat in front of his writing desk?”

![]() “Just so.”

“Just so.”

![]() “Sun in your eyes and his face in the shadow?”

“Sun in your eyes and his face in the shadow?”

![]() “Well, it was evening; but I mind that the lamp was

turned on my face.”

“Well, it was evening; but I mind that the lamp was

turned on my face.”

![]() “It would be. Did you happen to observe a picture over

the professor’s head?”

“It would be. Did you happen to observe a picture over

the professor’s head?”

![]() “I don’t miss much, Mr. Holmes. Maybe I learned that

from you. Yes, I saw the picture–a young woman with her head on her hands, peeping at

you sideways.”

“I don’t miss much, Mr. Holmes. Maybe I learned that

from you. Yes, I saw the picture–a young woman with her head on her hands, peeping at

you sideways.”

![]() “That painting was by Jean Baptiste Greuze.”

“That painting was by Jean Baptiste Greuze.”

![]() [776] The

inspector endeavoured to look interested.

[776] The

inspector endeavoured to look interested.

![]() “Jean Baptiste Greuze,” Holmes continued, joining

his finger tips and leaning well back in his chair, “was a French artist who

flourished between the years 1750 and 1800. I allude, of course, to his working career.

Modern criticism has more than indorsed the high opinion formed of him by his

contemporaries.”

“Jean Baptiste Greuze,” Holmes continued, joining

his finger tips and leaning well back in his chair, “was a French artist who

flourished between the years 1750 and 1800. I allude, of course, to his working career.

Modern criticism has more than indorsed the high opinion formed of him by his

contemporaries.”

![]() The inspector’s eyes grew abstracted. “Hadn’t

we better– –” he said.

The inspector’s eyes grew abstracted. “Hadn’t

we better– –” he said.

![]() “We are doing so,” Holmes interrupted. “All

that I am saying has a very direct and vital bearing upon what you have called the

Birlstone Mystery. In fact, it may in a sense be called the very centre of it.”

“We are doing so,” Holmes interrupted. “All

that I am saying has a very direct and vital bearing upon what you have called the

Birlstone Mystery. In fact, it may in a sense be called the very centre of it.”

![]() MacDonald smiled feebly, and looked appealingly to me.

“Your thoughts move a bit too quick for me, Mr. Holmes. You leave out a link or two,

and I can’t get over the gap. What in the whole wide world can be the connection

between this dead painting man and the affair at Birlstone?”

MacDonald smiled feebly, and looked appealingly to me.

“Your thoughts move a bit too quick for me, Mr. Holmes. You leave out a link or two,

and I can’t get over the gap. What in the whole wide world can be the connection

between this dead painting man and the affair at Birlstone?”

![]() “All knowledge comes useful to the detective,”

remarked Holmes. “Even the trivial fact that in the year 1865 a picture by Greuze

entitled La Jeune Fille a l’Agneau fetched one million two hundred thousand

francs–more than forty thousand pounds–at the Portalis sale may start a train of

reflection in your mind.”

“All knowledge comes useful to the detective,”

remarked Holmes. “Even the trivial fact that in the year 1865 a picture by Greuze

entitled La Jeune Fille a l’Agneau fetched one million two hundred thousand

francs–more than forty thousand pounds–at the Portalis sale may start a train of

reflection in your mind.”

![]() It was clear that it did. The inspector looked honestly

interested.

It was clear that it did. The inspector looked honestly

interested.

![]() “I may remind you,” Holmes continued, “that the

professor’s salary can be ascertained in several trustworthy books of reference. It

is seven hundred a year.”

“I may remind you,” Holmes continued, “that the

professor’s salary can be ascertained in several trustworthy books of reference. It

is seven hundred a year.”

![]() “Then how could he buy– –”

“Then how could he buy– –”

![]() “Quite so! How could he?”

“Quite so! How could he?”

![]() “Ay, that’s remarkable,” said the inspector

thoughtfully. “Talk away, Mr. Holmes. I’m just loving it. It’s fine!”

“Ay, that’s remarkable,” said the inspector

thoughtfully. “Talk away, Mr. Holmes. I’m just loving it. It’s fine!”

![]() Holmes smiled. He was always warmed by genuine

admiration–the characteristic of the real artist. “What about Birlstone?”

he asked.

Holmes smiled. He was always warmed by genuine

admiration–the characteristic of the real artist. “What about Birlstone?”

he asked.

![]() “We’ve time yet,” said the inspector, glancing

at his watch. “I’ve a cab at the door, and it won’t take us twenty minutes

to Victoria. But about this picture: I thought you told me once, Mr. Holmes, that you had

never met Professor Moriarty.”

“We’ve time yet,” said the inspector, glancing

at his watch. “I’ve a cab at the door, and it won’t take us twenty minutes

to Victoria. But about this picture: I thought you told me once, Mr. Holmes, that you had

never met Professor Moriarty.”

![]() “No, I never have.”

“No, I never have.”

![]() “Then how do you know about his rooms?”

“Then how do you know about his rooms?”

![]() “Ah, that’s another matter. I have been three times

in his rooms, twice waiting for him under different pretexts and leaving before he came.

Once– well, I can hardly tell about the once to an official detective. It was on the

last occasion that I took the liberty of running over his papers–with the most

unexpected results.”

“Ah, that’s another matter. I have been three times

in his rooms, twice waiting for him under different pretexts and leaving before he came.

Once– well, I can hardly tell about the once to an official detective. It was on the

last occasion that I took the liberty of running over his papers–with the most

unexpected results.”

![]() “You found something compromising?”

“You found something compromising?”

![]() “Absolutely nothing. That was what amazed me. However,

you have now seen the point of the picture. It shows him to be a very wealthy man. How did

he acquire wealth? He is unmarried. His younger brother is a station master in the west of

England. His chair is worth seven hundred a year. And he owns a Greuze.”

“Absolutely nothing. That was what amazed me. However,

you have now seen the point of the picture. It shows him to be a very wealthy man. How did

he acquire wealth? He is unmarried. His younger brother is a station master in the west of

England. His chair is worth seven hundred a year. And he owns a Greuze.”

![]() “Well?”

“Well?”

![]() “Surely the inference is plain.”

“Surely the inference is plain.”

![]() “You mean that he has a great income and that he must

earn it in an illegal fashion?”

“You mean that he has a great income and that he must

earn it in an illegal fashion?”

![]() “Exactly. Of course I have other reasons for thinking

so–dozens of exiguous threads which lead vaguely up towards the centre of the web

where the poisonous, motionless creature is lurking. I only mention the Greuze because it

brings the matter within the range of your own observation.”

“Exactly. Of course I have other reasons for thinking

so–dozens of exiguous threads which lead vaguely up towards the centre of the web

where the poisonous, motionless creature is lurking. I only mention the Greuze because it

brings the matter within the range of your own observation.”

![]() [777] “Well,

Mr. Holmes, I admit that what you say is interesting: it’s more than

interesting–it’s just wonderful. But let us have it a little clearer if you can.

Is it forgery, coining, burglary–where does the money come from?”

[777] “Well,

Mr. Holmes, I admit that what you say is interesting: it’s more than

interesting–it’s just wonderful. But let us have it a little clearer if you can.

Is it forgery, coining, burglary–where does the money come from?”

![]() “Have you ever read of Jonathan Wild?”

“Have you ever read of Jonathan Wild?”

![]() “Well, the name has a familiar sound. Someone in a novel,

was he not? I don’t take much stock of detectives in novels–chaps that do things

and never let you see how they do them. That’s just inspiration: not business.”

“Well, the name has a familiar sound. Someone in a novel,

was he not? I don’t take much stock of detectives in novels–chaps that do things

and never let you see how they do them. That’s just inspiration: not business.”

![]() “Jonathan Wild wasn’t a detective, and he

wasn’t in a novel. He was a master criminal, and he lived last century–1750 or

thereabouts.”

“Jonathan Wild wasn’t a detective, and he

wasn’t in a novel. He was a master criminal, and he lived last century–1750 or

thereabouts.”

![]() “Then he’s no use to me. I’m a practical

man.”

“Then he’s no use to me. I’m a practical

man.”

![]() “Mr. Mac, the most practical thing that you ever did in

your life would be to shut yourself up for three months and read twelve hours a day at the

annals of crime. Everything comes in circles–even Professor Moriarty. Jonathan Wild

was the hidden force of the London criminals, to whom he sold his brains and his

organization on a fifteen per cent. commission. The old wheel turns, and the same spoke

comes up. It’s all been done before, and will be again. I’ll tell you one or two

things about Moriarty which may interest you.”

“Mr. Mac, the most practical thing that you ever did in

your life would be to shut yourself up for three months and read twelve hours a day at the

annals of crime. Everything comes in circles–even Professor Moriarty. Jonathan Wild

was the hidden force of the London criminals, to whom he sold his brains and his

organization on a fifteen per cent. commission. The old wheel turns, and the same spoke

comes up. It’s all been done before, and will be again. I’ll tell you one or two

things about Moriarty which may interest you.”

![]() “You’ll interest me, right enough.”

“You’ll interest me, right enough.”

![]() “I happen to know who is the first link in his

chain–a chain with this Napoleon-gone-wrong at one end, and a hundred broken fighting

men, pickpockets, blackmailers, and card sharpers at the other, with every sort of crime

in between. His chief of staff is Colonel Sebastian Moran, as aloof and guarded and

inaccessible to the law as himself. What do you think he pays him?”

“I happen to know who is the first link in his

chain–a chain with this Napoleon-gone-wrong at one end, and a hundred broken fighting

men, pickpockets, blackmailers, and card sharpers at the other, with every sort of crime

in between. His chief of staff is Colonel Sebastian Moran, as aloof and guarded and

inaccessible to the law as himself. What do you think he pays him?”

![]() “I’d like to hear.”

“I’d like to hear.”

![]() “Six thousand a year. That’s paying for brains, you

see–the American business principle. I learned that detail quite by chance. It’s

more than the Prime Minister gets. That gives you an idea of Moriarty’s gains and of

the scale on which he works. Another point: I made it my business to hunt down some of

Moriarty’s checks lately–just common innocent checks that he pays his household

bills with. They were drawn on six different banks. Does that make any impression on your

mind?”

“Six thousand a year. That’s paying for brains, you

see–the American business principle. I learned that detail quite by chance. It’s

more than the Prime Minister gets. That gives you an idea of Moriarty’s gains and of

the scale on which he works. Another point: I made it my business to hunt down some of

Moriarty’s checks lately–just common innocent checks that he pays his household

bills with. They were drawn on six different banks. Does that make any impression on your

mind?”

![]() “Queer, certainly! But what do you gather from it?”

“Queer, certainly! But what do you gather from it?”

![]() “That he wanted no gossip about his wealth. No single man

should know what he had. I have no doubt that he has twenty banking accounts; the bulk of

his fortune abroad in the Deutsche Bank or the Credit Lyonnais as likely as not. Sometime

when you have a year or two to spare I commend to you the study of Professor

Moriarty.”

“That he wanted no gossip about his wealth. No single man

should know what he had. I have no doubt that he has twenty banking accounts; the bulk of

his fortune abroad in the Deutsche Bank or the Credit Lyonnais as likely as not. Sometime

when you have a year or two to spare I commend to you the study of Professor

Moriarty.”

![]() Inspector MacDonald had grown steadily more impressed as the

conversation proceeded. He had lost himself in his interest. Now his practical Scotch

intelligence brought him back with a snap to the matter in hand.

Inspector MacDonald had grown steadily more impressed as the

conversation proceeded. He had lost himself in his interest. Now his practical Scotch

intelligence brought him back with a snap to the matter in hand.

![]() “He can keep, anyhow,” said he. “You’ve

got us side-tracked with your interesting anecdotes, Mr. Holmes. What really counts is

your remark that there is some connection between the professor and the crime. That you

get from the warning received through the man Porlock. Can we for our present practical

needs get any further than that?”

“He can keep, anyhow,” said he. “You’ve

got us side-tracked with your interesting anecdotes, Mr. Holmes. What really counts is

your remark that there is some connection between the professor and the crime. That you

get from the warning received through the man Porlock. Can we for our present practical

needs get any further than that?”

![]() “We may form some conception as to the motives of the

crime. It is, as I gather from your original remarks, an inexplicable, or at least an

unexplained, murder. Now, presuming that the source of the crime is as we suspect it to

be, there might be two different motives. In the first place, I may tell you that Moriarty

rules with a rod of iron over his people. His discipline is tremendous. There is only one [778] punishment in his code. It is

death. Now we might suppose that this murdered man–this Douglas whose approaching

fate was known by one of the arch-criminal’s subordinates–had in some way

betrayed the chief. His punishment followed, and would be known to all–if only to put

the fear of death into them.”

“We may form some conception as to the motives of the

crime. It is, as I gather from your original remarks, an inexplicable, or at least an

unexplained, murder. Now, presuming that the source of the crime is as we suspect it to

be, there might be two different motives. In the first place, I may tell you that Moriarty

rules with a rod of iron over his people. His discipline is tremendous. There is only one [778] punishment in his code. It is

death. Now we might suppose that this murdered man–this Douglas whose approaching

fate was known by one of the arch-criminal’s subordinates–had in some way

betrayed the chief. His punishment followed, and would be known to all–if only to put

the fear of death into them.”

![]() “Well, that is one suggestion, Mr. Holmes.”

“Well, that is one suggestion, Mr. Holmes.”

![]() “The other is that it has been engineered by Moriarty in

the ordinary course of business. Was there any robbery?”

“The other is that it has been engineered by Moriarty in

the ordinary course of business. Was there any robbery?”

![]() “I have not heard.”

“I have not heard.”

![]() “If so, it would, of course, be against the first

hypothesis and in favour of the second. Moriarty may have been engaged to engineer it on a

promise of part spoils, or he may have been paid so much down to manage it. Either is

possible. But whichever it may be, or if it is some third combination, it is down at

Birlstone that we must seek the solution. I know our man too well to suppose that he has

left anything up here which may lead us to him.”

“If so, it would, of course, be against the first

hypothesis and in favour of the second. Moriarty may have been engaged to engineer it on a

promise of part spoils, or he may have been paid so much down to manage it. Either is

possible. But whichever it may be, or if it is some third combination, it is down at

Birlstone that we must seek the solution. I know our man too well to suppose that he has

left anything up here which may lead us to him.”

![]() “Then to Birlstone we must go!” cried MacDonald,

jumping from his chair. “My word! it’s later than I thought. I can give you,

gentlemen, five minutes for preparation, and that is all.”

“Then to Birlstone we must go!” cried MacDonald,

jumping from his chair. “My word! it’s later than I thought. I can give you,

gentlemen, five minutes for preparation, and that is all.”

![]() “And ample for us both,” said Holmes, as he sprang

up and hastened to change from his dressing gown to his coat. “While we are on our

way, Mr. Mac, I will ask you to be good enough to tell me all about it.”

“And ample for us both,” said Holmes, as he sprang

up and hastened to change from his dressing gown to his coat. “While we are on our

way, Mr. Mac, I will ask you to be good enough to tell me all about it.”

![]() “All about it” proved to be disappointingly little,

and yet there was enough to assure us that the case before us might well be worthy of the

expert’s closest attention. He brightened and rubbed his thin hands together as he

listened to the meagre but remarkable details. A long series of sterile weeks lay behind

us, and here at last there was a fitting object for those remarkable powers which, like

all special gifts, become irksome to their owner when they are not in use. That razor

brain blunted and rusted with inaction.

“All about it” proved to be disappointingly little,

and yet there was enough to assure us that the case before us might well be worthy of the

expert’s closest attention. He brightened and rubbed his thin hands together as he

listened to the meagre but remarkable details. A long series of sterile weeks lay behind

us, and here at last there was a fitting object for those remarkable powers which, like

all special gifts, become irksome to their owner when they are not in use. That razor

brain blunted and rusted with inaction.

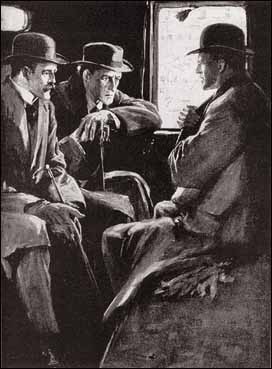

![]() Sherlock Holmes’s eyes glistened, his pale cheeks took

a warmer hue, and his whole eager face shone with an inward light when the call for work

reached him. Leaning forward in the cab, he listened intently to MacDonald’s short

sketch of the problem which awaited us in Sussex. The inspector was himself dependent, as

he explained to us, upon a scribbled account forwarded to him by the milk train in the

early hours of the morning. White Mason, the local officer, was a personal friend, and

hence MacDonald had been notified much more promptly than is usual at Scotland Yard when

provincials need their assistance. It is a very cold scent upon which the Metropolitan

expert is generally asked to run.

Sherlock Holmes’s eyes glistened, his pale cheeks took

a warmer hue, and his whole eager face shone with an inward light when the call for work

reached him. Leaning forward in the cab, he listened intently to MacDonald’s short

sketch of the problem which awaited us in Sussex. The inspector was himself dependent, as

he explained to us, upon a scribbled account forwarded to him by the milk train in the

early hours of the morning. White Mason, the local officer, was a personal friend, and

hence MacDonald had been notified much more promptly than is usual at Scotland Yard when

provincials need their assistance. It is a very cold scent upon which the Metropolitan

expert is generally asked to run.

- “DEAR INSPECTOR MACDONALD [said

the letter which he read to us]:

“Official requisition for your services is in separate

envelope. This is for your private eye. Wire me what train in the morning you can get for

Birlstone, and I will meet it–or have it met if I am too occupied. This case is a

snorter. Don’t waste a moment in getting started. If you can bring Mr. Holmes, please

do so; for he will find something after his own heart. We would think the whole thing had

been fixed up for theatrical effect if there wasn’t a dead man in the middle of it.

My word! it is a snorter.”

“Official requisition for your services is in separate

envelope. This is for your private eye. Wire me what train in the morning you can get for

Birlstone, and I will meet it–or have it met if I am too occupied. This case is a

snorter. Don’t waste a moment in getting started. If you can bring Mr. Holmes, please

do so; for he will find something after his own heart. We would think the whole thing had

been fixed up for theatrical effect if there wasn’t a dead man in the middle of it.

My word! it is a snorter.”

![]() “Your friend seems to be no fool,” remarked

Holmes.

“Your friend seems to be no fool,” remarked

Holmes.

![]() “No, sir, White Mason is a very live man, if I am any

judge.”

“No, sir, White Mason is a very live man, if I am any

judge.”

![]() “Well, have you anything more?”

“Well, have you anything more?”

![]() “Only that he will give us every detail when we

meet.”

“Only that he will give us every detail when we

meet.”

![]() [779] “Then

how did you get at Mr. Douglas and the fact that he had been horribly murdered?”

[779] “Then

how did you get at Mr. Douglas and the fact that he had been horribly murdered?”

![]() “That was in the inclosed official report. It didn’t

say ‘horrible’: that’s not a recognized official term. It gave the name

John Douglas. It mentioned that his injuries had been in the head, from the discharge of a

shotgun. It also mentioned the hour of the alarm, which was close on to midnight last

night. It added that the case was undoubtedly one of murder, but that no arrest had been

made, and that the case was one which presented some very perplexing and extraordinary

features. That’s absolutely all we have at present, Mr. Holmes.”

“That was in the inclosed official report. It didn’t

say ‘horrible’: that’s not a recognized official term. It gave the name

John Douglas. It mentioned that his injuries had been in the head, from the discharge of a

shotgun. It also mentioned the hour of the alarm, which was close on to midnight last

night. It added that the case was undoubtedly one of murder, but that no arrest had been

made, and that the case was one which presented some very perplexing and extraordinary

features. That’s absolutely all we have at present, Mr. Holmes.”

![]() “Then, with your permission, we will leave it at that,

Mr. Mac. The temptation to form premature theories upon insufficient data is the bane of

our profession. I can see only two things for certain at present–a great brain in

London, and a dead man in Sussex. It’s the chain between that we are going to

trace.”

“Then, with your permission, we will leave it at that,

Mr. Mac. The temptation to form premature theories upon insufficient data is the bane of

our profession. I can see only two things for certain at present–a great brain in

London, and a dead man in Sussex. It’s the chain between that we are going to

trace.”

![]()