|

|

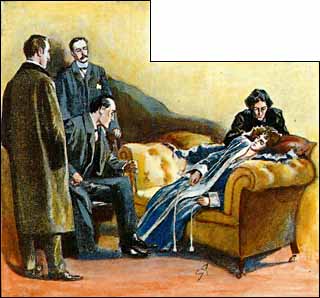

“I am the wife of Sir Eustace Brackenstall. I have been

married about a year. I suppose that it is no use my attempting to conceal that our

marriage has not been a happy one. I fear that all our neighbours would tell you that,

even if I were to attempt to deny it. Perhaps the fault may be partly mine. I was brought

up in the freer, less conventional atmosphere of South Australia, and this English life,

with its proprieties and its primness, is not congenial to me. But the main reason lies in

the one fact, which is notorious to everyone, and that is that Sir Eustace was a confirmed

drunkard. To be with such a man for an hour is unpleasant. Can you imagine what it means

for a sensitive and high-spirited woman to be tied to him for day and night? It is a

sacrilege, a crime, a villainy to hold that such a marriage is binding. I say that these

monstrous laws of yours will bring a curse upon the land–God will not let such

wickedness endure.” For an instant she sat up, her cheeks flushed, and her eyes

blazing from under the terrible mark upon her brow. Then the strong, soothing hand of the

austere maid drew her head down on to the cushion, and the wild anger died away into

passionate sobbing. At last she continued: “I am the wife of Sir Eustace Brackenstall. I have been

married about a year. I suppose that it is no use my attempting to conceal that our

marriage has not been a happy one. I fear that all our neighbours would tell you that,

even if I were to attempt to deny it. Perhaps the fault may be partly mine. I was brought

up in the freer, less conventional atmosphere of South Australia, and this English life,

with its proprieties and its primness, is not congenial to me. But the main reason lies in

the one fact, which is notorious to everyone, and that is that Sir Eustace was a confirmed

drunkard. To be with such a man for an hour is unpleasant. Can you imagine what it means

for a sensitive and high-spirited woman to be tied to him for day and night? It is a

sacrilege, a crime, a villainy to hold that such a marriage is binding. I say that these

monstrous laws of yours will bring a curse upon the land–God will not let such

wickedness endure.” For an instant she sat up, her cheeks flushed, and her eyes

blazing from under the terrible mark upon her brow. Then the strong, soothing hand of the

austere maid drew her head down on to the cushion, and the wild anger died away into

passionate sobbing. At last she continued:

“I will tell you about last night. You are aware,

perhaps, that in this house all the servants sleep in the modern wing. This central block

is made up of the dwelling-rooms, with the kitchen behind and our bedroom above. My maid,

Theresa, sleeps above my room. There is no one else, and no sound could alarm those who

are in the farther wing. This must have been well known to the robbers, or they would not

have acted as they did. “I will tell you about last night. You are aware,

perhaps, that in this house all the servants sleep in the modern wing. This central block

is made up of the dwelling-rooms, with the kitchen behind and our bedroom above. My maid,

Theresa, sleeps above my room. There is no one else, and no sound could alarm those who

are in the farther wing. This must have been well known to the robbers, or they would not

have acted as they did.

“Sir Eustace retired about half-past ten. The servants

had already gone to their quarters. Only my maid was up, and she had remained in her room

at the top of the house until I needed her services. I sat until after eleven in this

room, absorbed in a book. Then I walked round to see that all was right before I went

upstairs. It was my custom to do this myself, for, as I have explained, Sir Eustace was

not always to be trusted. I went into the kitchen, the butler’s pantry, the gun-room,

the billiard-room, the drawing-room, and finally the dining-room. As I approached the

window, which is covered with thick curtains, I suddenly felt the wind blow upon my face

and realized that it was open. I flung the curtain aside and found myself face to face

with a broad-shouldered elderly man, who had just stepped into the room. The window is a

long French one, which really forms a door leading to the lawn. I held my bedroom candle

lit in my hand, and, by its light, behind the first man I saw two others, who were in the

act of entering. I stepped back, but the fellow was on me in an instant. He caught me

first by the wrist and then by the throat. I opened my mouth to scream, but he struck me a

savage blow with his fist over the eye, and felled me to the ground. I must have been

unconscious for a few minutes, for when I came to myself, I found that they had torn down

the bell-rope, and had secured me tightly to the oaken chair which stands at the head of

the dining-table. I was so firmly bound that I could not move, and a handkerchief round my

mouth prevented me from uttering a sound. It was at this instant that my unfortunate

husband entered the room. He had evidently heard some suspicious sounds, and he came

prepared for such a scene as he found. He was dressed in nightshirt and trousers, with his

favourite blackthorn cudgel in his hand. He rushed at the burglars, but another–it

was an elderly man–stooped, picked the poker out of the grate and struck him a

horrible blow as he passed. He [639] fell

with a groan and never moved again. I fainted once more, but again it could only have been

for a very few minutes during which I was insensible. When I opened my eyes I found that

they had collected the silver from the sideboard, and they had drawn a bottle of wine

which stood there. Each of them had a glass in his hand. I have already told you, have I

not, that one was elderly, with a beard, and the others young, hairless lads. They might

have been a father with his two sons. They talked together in whispers. Then they came

over and made sure that I was securely bound. Finally they withdrew, closing the window

after them. It was quite a quarter of an hour before I got my mouth free. When I did so,

my screams brought the maid to my assistance. The other servants were soon alarmed, and we

sent for the local police, who instantly communicated with London. That is really all that

I can tell you, gentlemen, and I trust that it will not be necessary for me to go over so

painful a story again.” “Sir Eustace retired about half-past ten. The servants

had already gone to their quarters. Only my maid was up, and she had remained in her room

at the top of the house until I needed her services. I sat until after eleven in this

room, absorbed in a book. Then I walked round to see that all was right before I went

upstairs. It was my custom to do this myself, for, as I have explained, Sir Eustace was

not always to be trusted. I went into the kitchen, the butler’s pantry, the gun-room,

the billiard-room, the drawing-room, and finally the dining-room. As I approached the

window, which is covered with thick curtains, I suddenly felt the wind blow upon my face

and realized that it was open. I flung the curtain aside and found myself face to face

with a broad-shouldered elderly man, who had just stepped into the room. The window is a

long French one, which really forms a door leading to the lawn. I held my bedroom candle

lit in my hand, and, by its light, behind the first man I saw two others, who were in the

act of entering. I stepped back, but the fellow was on me in an instant. He caught me

first by the wrist and then by the throat. I opened my mouth to scream, but he struck me a

savage blow with his fist over the eye, and felled me to the ground. I must have been

unconscious for a few minutes, for when I came to myself, I found that they had torn down

the bell-rope, and had secured me tightly to the oaken chair which stands at the head of

the dining-table. I was so firmly bound that I could not move, and a handkerchief round my

mouth prevented me from uttering a sound. It was at this instant that my unfortunate

husband entered the room. He had evidently heard some suspicious sounds, and he came

prepared for such a scene as he found. He was dressed in nightshirt and trousers, with his

favourite blackthorn cudgel in his hand. He rushed at the burglars, but another–it

was an elderly man–stooped, picked the poker out of the grate and struck him a

horrible blow as he passed. He [639] fell

with a groan and never moved again. I fainted once more, but again it could only have been

for a very few minutes during which I was insensible. When I opened my eyes I found that

they had collected the silver from the sideboard, and they had drawn a bottle of wine

which stood there. Each of them had a glass in his hand. I have already told you, have I

not, that one was elderly, with a beard, and the others young, hairless lads. They might

have been a father with his two sons. They talked together in whispers. Then they came

over and made sure that I was securely bound. Finally they withdrew, closing the window

after them. It was quite a quarter of an hour before I got my mouth free. When I did so,

my screams brought the maid to my assistance. The other servants were soon alarmed, and we

sent for the local police, who instantly communicated with London. That is really all that

I can tell you, gentlemen, and I trust that it will not be necessary for me to go over so

painful a story again.”

“Any questions, Mr. Holmes?” asked Hopkins. “Any questions, Mr. Holmes?” asked Hopkins.

“I will not impose any further tax upon Lady

Brackenstall’s patience and time,” said Holmes. “Before I go into the

dining-room, I should like to hear your experience.” He looked at the maid. “I will not impose any further tax upon Lady

Brackenstall’s patience and time,” said Holmes. “Before I go into the

dining-room, I should like to hear your experience.” He looked at the maid.

“I saw the men before ever they came into the

house,” said she. “As I sat by my bedroom window I saw three men in the

moonlight down by the lodge gate yonder, but I thought nothing of it at the time. It was

more than an hour after that I heard my mistress scream, and down I ran, to find her, poor

lamb, just as she says, and him on the floor, with his blood and brains over the room. It

was enough to drive a woman out of her wits, tied there, and her very dress spotted with

him, but she never wanted courage, did Miss Mary Fraser of Adelaide and Lady Brackenstall

of Abbey Grange hasn’t learned new ways. You’ve questioned her long enough, you

gentlemen, and now she is coming to her own room, just with her old Theresa, to get the

rest that she badly needs.” “I saw the men before ever they came into the

house,” said she. “As I sat by my bedroom window I saw three men in the

moonlight down by the lodge gate yonder, but I thought nothing of it at the time. It was

more than an hour after that I heard my mistress scream, and down I ran, to find her, poor

lamb, just as she says, and him on the floor, with his blood and brains over the room. It

was enough to drive a woman out of her wits, tied there, and her very dress spotted with

him, but she never wanted courage, did Miss Mary Fraser of Adelaide and Lady Brackenstall

of Abbey Grange hasn’t learned new ways. You’ve questioned her long enough, you

gentlemen, and now she is coming to her own room, just with her old Theresa, to get the

rest that she badly needs.”

With a motherly tenderness the gaunt woman put her arm round

her mistress and led her from the room. With a motherly tenderness the gaunt woman put her arm round

her mistress and led her from the room.

“She has been with her all her life,” said Hopkins.

“Nursed her as a baby, and came with her to England when they first left Australia,

eighteen months ago. Theresa Wright is her name, and the kind of maid you don’t pick

up nowadays. This way, Mr. Holmes, if you please!” “She has been with her all her life,” said Hopkins.

“Nursed her as a baby, and came with her to England when they first left Australia,

eighteen months ago. Theresa Wright is her name, and the kind of maid you don’t pick

up nowadays. This way, Mr. Holmes, if you please!”

The keen interest had passed out of Holmes’s expressive

face, and I knew that with the mystery all the charm of the case had departed. There still

remained an arrest to be effected, but what were these commonplace rogues that he should

soil his hands with them? An abstruse and learned specialist who finds that he has been

called in for a case of measles would experience something of the annoyance which I read

in my friend’s eyes. Yet the scene in the dining-room of the Abbey Grange was

sufficiently strange to arrest his attention and to recall his waning interest. The keen interest had passed out of Holmes’s expressive

face, and I knew that with the mystery all the charm of the case had departed. There still

remained an arrest to be effected, but what were these commonplace rogues that he should

soil his hands with them? An abstruse and learned specialist who finds that he has been

called in for a case of measles would experience something of the annoyance which I read

in my friend’s eyes. Yet the scene in the dining-room of the Abbey Grange was

sufficiently strange to arrest his attention and to recall his waning interest.

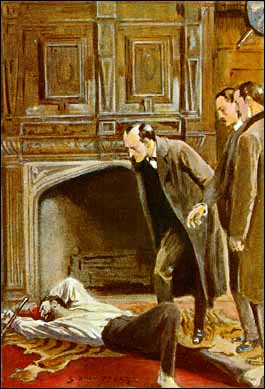

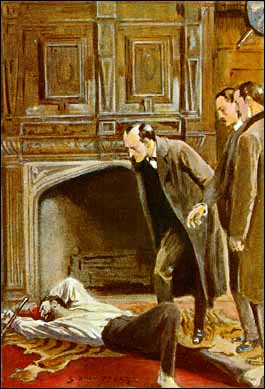

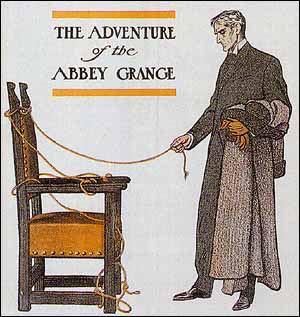

It was a very large and high chamber, with carved oak ceiling,

oaken panelling, and a fine array of deer’s heads and ancient weapons around the

walls. At the further end from the door was the high French window of which we had heard.

Three smaller windows on the right-hand side filled the apartment with cold winter

sunshine. On the left was a large, deep fireplace, with a massive, overhanging oak

mantelpiece. Beside the fireplace was a heavy oaken chair with arms and crossbars at the

bottom. In and out through the open woodwork was woven a crimson cord, which was secured

at each side to the crosspiece below. In releasing the [640] lady, the cord had been slipped off her, but the knots

with which it had been secured still remained. These details only struck our attention

afterwards, for our thoughts were entirely absorbed by the terrible object which lay upon

the tiger-skin hearthrug in front of the fire. It was a very large and high chamber, with carved oak ceiling,

oaken panelling, and a fine array of deer’s heads and ancient weapons around the

walls. At the further end from the door was the high French window of which we had heard.

Three smaller windows on the right-hand side filled the apartment with cold winter

sunshine. On the left was a large, deep fireplace, with a massive, overhanging oak

mantelpiece. Beside the fireplace was a heavy oaken chair with arms and crossbars at the

bottom. In and out through the open woodwork was woven a crimson cord, which was secured

at each side to the crosspiece below. In releasing the [640] lady, the cord had been slipped off her, but the knots

with which it had been secured still remained. These details only struck our attention

afterwards, for our thoughts were entirely absorbed by the terrible object which lay upon

the tiger-skin hearthrug in front of the fire.

It was the body of a tall, well-made man, about forty years

of age. He lay upon his back, his face upturned, with his white teeth grinning through his

short, black beard. His two clenched hands were raised above his head, and a heavy,

blackthorn stick lay across them. His dark, handsome, aquiline features were convulsed

into a spasm of vindictive hatred, which had set his dead face in a terribly fiendish

expression. He had evidently been in his bed when the alarm had broken out, for he wore a

foppish, embroidered nightshirt, and his bare feet projected from his trousers. His head

was horribly injured, and the whole room bore witness to the savage ferocity of the blow

which had struck him down. Beside him lay the heavy poker, bent into a curve by the

concussion. Holmes examined both it and the indescribable wreck which it had wrought. It was the body of a tall, well-made man, about forty years

of age. He lay upon his back, his face upturned, with his white teeth grinning through his

short, black beard. His two clenched hands were raised above his head, and a heavy,

blackthorn stick lay across them. His dark, handsome, aquiline features were convulsed

into a spasm of vindictive hatred, which had set his dead face in a terribly fiendish

expression. He had evidently been in his bed when the alarm had broken out, for he wore a

foppish, embroidered nightshirt, and his bare feet projected from his trousers. His head

was horribly injured, and the whole room bore witness to the savage ferocity of the blow

which had struck him down. Beside him lay the heavy poker, bent into a curve by the

concussion. Holmes examined both it and the indescribable wreck which it had wrought.

“He must be a powerful man, this elder Randall,” he

remarked. “He must be a powerful man, this elder Randall,” he

remarked.

“Yes,” said Hopkins. “I have some record of the

fellow, and he is a rough customer.” “Yes,” said Hopkins. “I have some record of the

fellow, and he is a rough customer.”

“You should have no difficulty in getting him.” “You should have no difficulty in getting him.”

“Not the slightest. We have been on the look-out for him,

and there was some idea that he had got away to America. Now that we know that the gang

are here, I don’t see how they can escape. We have the news at every seaport already,

and a reward will be offered before evening. What beats me is how they could have done so

mad a thing, knowing that the lady could describe them and that we could not fail to

recognize the description.” “Not the slightest. We have been on the look-out for him,

and there was some idea that he had got away to America. Now that we know that the gang

are here, I don’t see how they can escape. We have the news at every seaport already,

and a reward will be offered before evening. What beats me is how they could have done so

mad a thing, knowing that the lady could describe them and that we could not fail to

recognize the description.”

“Exactly. One would have expected that they would silence

Lady Brackenstall as well.” “Exactly. One would have expected that they would silence

Lady Brackenstall as well.”

“They may not have realized,” I suggested,

“that she had recovered from her faint.” “They may not have realized,” I suggested,

“that she had recovered from her faint.”

“That is likely enough. If she seemed to be senseless,

they would not take her life. What about this poor fellow, Hopkins? I seem to have heard

some queer stories about him.” “That is likely enough. If she seemed to be senseless,

they would not take her life. What about this poor fellow, Hopkins? I seem to have heard

some queer stories about him.”

“He was a good-hearted man when he was sober, but a

perfect fiend when he was drunk, or rather when he was half drunk, for he seldom really

went the whole way. The devil seemed to be in him at such times, and he was capable of

anything. From what I hear, in spite of all his wealth and his title, he very nearly came

our way once or twice. There was a scandal about his drenching a dog with petroleum and

setting it on fire–her ladyship’s dog, to make the matter worse–and that

was only hushed up with difficulty. Then he threw a decanter at that maid, Theresa

Wright–there was trouble about that. On the whole, and between ourselves, it will be

a brighter house without him. What are you looking at now?” “He was a good-hearted man when he was sober, but a

perfect fiend when he was drunk, or rather when he was half drunk, for he seldom really

went the whole way. The devil seemed to be in him at such times, and he was capable of

anything. From what I hear, in spite of all his wealth and his title, he very nearly came

our way once or twice. There was a scandal about his drenching a dog with petroleum and

setting it on fire–her ladyship’s dog, to make the matter worse–and that

was only hushed up with difficulty. Then he threw a decanter at that maid, Theresa

Wright–there was trouble about that. On the whole, and between ourselves, it will be

a brighter house without him. What are you looking at now?”

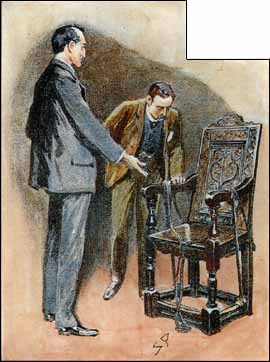

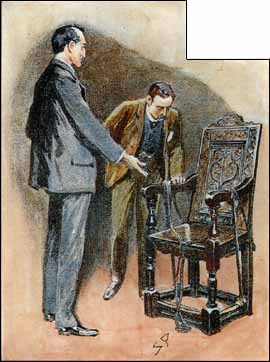

Holmes was down on his knees, examining with great attention

the knots upon the red cord with which the lady had been secured. Then he carefully

scrutinized the broken and frayed end where it had snapped off when the burglar had

dragged it down. Holmes was down on his knees, examining with great attention

the knots upon the red cord with which the lady had been secured. Then he carefully

scrutinized the broken and frayed end where it had snapped off when the burglar had

dragged it down.

“When this was pulled down, the bell in the kitchen must

have rung loudly,” he remarked. “When this was pulled down, the bell in the kitchen must

have rung loudly,” he remarked.

“No one could hear it. The kitchen stands right at the

back of the house.” “No one could hear it. The kitchen stands right at the

back of the house.”

[641] “How

did the burglar know no one would hear it? How dared he pull at a bell-rope in that

reckless fashion?” [641] “How

did the burglar know no one would hear it? How dared he pull at a bell-rope in that

reckless fashion?”

“Exactly, Mr. Holmes, exactly. You put the very question

which I have asked myself again and again. There can be no doubt that this fellow must

have known the house and its habits. He must have perfectly understood that the servants

would all be in bed at that comparatively early hour, and that no one could possibly hear

a bell ring in the kitchen. Therefore, he must have been in close league with one of the

servants. Surely that is evident. But there are eight servants, and all of good

character.” “Exactly, Mr. Holmes, exactly. You put the very question

which I have asked myself again and again. There can be no doubt that this fellow must

have known the house and its habits. He must have perfectly understood that the servants

would all be in bed at that comparatively early hour, and that no one could possibly hear

a bell ring in the kitchen. Therefore, he must have been in close league with one of the

servants. Surely that is evident. But there are eight servants, and all of good

character.”

“Other things being equal,” said Holmes, “one

would suspect the one at whose head the master threw a decanter. And yet that would

involve treachery towards the mistress to whom this woman seems devoted. Well, well, the

point is a minor one, and when you have Randall you will probably find no difficulty in

securing his accomplice. The lady’s story certainly seems to be corroborated, if it

needed corroboration, by every detail which we see before us.” He walked to the

French window and threw it open. “There are no signs here, but the ground is iron

hard, and one would not expect them. I see that these candles in the mantelpiece have been

lighted.” “Other things being equal,” said Holmes, “one

would suspect the one at whose head the master threw a decanter. And yet that would

involve treachery towards the mistress to whom this woman seems devoted. Well, well, the

point is a minor one, and when you have Randall you will probably find no difficulty in

securing his accomplice. The lady’s story certainly seems to be corroborated, if it

needed corroboration, by every detail which we see before us.” He walked to the

French window and threw it open. “There are no signs here, but the ground is iron

hard, and one would not expect them. I see that these candles in the mantelpiece have been

lighted.”

“Yes, it was by their light, and that of the lady’s

bedroom candle, that the burglars saw their way about.” “Yes, it was by their light, and that of the lady’s

bedroom candle, that the burglars saw their way about.”

“And what did they take?” “And what did they take?”

“Well, they did not take much–only half a dozen

articles of plate off the sideboard. Lady Brackenstall thinks that they were themselves so

disturbed by the death of Sir Eustace that they did not ransack the house, as they would

otherwise have done.” “Well, they did not take much–only half a dozen

articles of plate off the sideboard. Lady Brackenstall thinks that they were themselves so

disturbed by the death of Sir Eustace that they did not ransack the house, as they would

otherwise have done.”

“No doubt that is true, and yet they drank some wine, I

understand.” “No doubt that is true, and yet they drank some wine, I

understand.”

“To steady their nerves.” “To steady their nerves.”

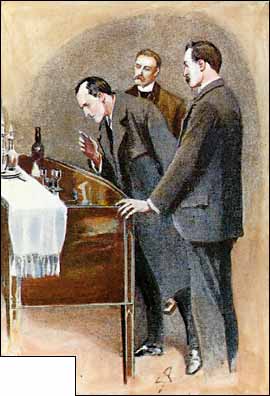

“Exactly. These three glasses upon the sideboard have

been untouched, I suppose?” “Exactly. These three glasses upon the sideboard have

been untouched, I suppose?”

“Yes, and the bottle stands as they left it.” “Yes, and the bottle stands as they left it.”

“Let us look at it. Halloa, halloa! What is

this?” “Let us look at it. Halloa, halloa! What is

this?”

The three glasses were grouped together, all of them tinged

with wine, and one of them containing some dregs of beeswing. The bottle stood near them,

two-thirds full, and beside it lay a long, deeply stained cork. Its appearance and the

dust upon the bottle showed that it was no common vintage which the murderers had enjoyed. The three glasses were grouped together, all of them tinged

with wine, and one of them containing some dregs of beeswing. The bottle stood near them,

two-thirds full, and beside it lay a long, deeply stained cork. Its appearance and the

dust upon the bottle showed that it was no common vintage which the murderers had enjoyed.

A change had come over Holmes’s manner. He had lost

his listless expression, and again I saw an alert light of interest in his keen, deep-set

eyes. He raised the cork and examined it minutely. A change had come over Holmes’s manner. He had lost

his listless expression, and again I saw an alert light of interest in his keen, deep-set

eyes. He raised the cork and examined it minutely.

“How did they draw it?” he asked. “How did they draw it?” he asked.

Hopkins pointed to a half-opened drawer. In it lay some table

linen and a large corkscrew. Hopkins pointed to a half-opened drawer. In it lay some table

linen and a large corkscrew.

“Did Lady Brackenstall say that screw was used?” “Did Lady Brackenstall say that screw was used?”

“No, you remember that she was senseless at the moment

when the bottle was opened.” “No, you remember that she was senseless at the moment

when the bottle was opened.”

“Quite so. As a matter of fact, that screw was not used.

This bottle was opened by a pocket screw, probably contained in a knife, and not more than

an inch and a half long. If you will examine the top of the cork, you will observe that

the screw was driven in three times before the cork was extracted. It has never been [642] transfixed. This long screw

would have transfixed it and drawn it up with a single pull. When you catch this fellow,

you will find that he has one of these multiplex knives in his possession.” “Quite so. As a matter of fact, that screw was not used.

This bottle was opened by a pocket screw, probably contained in a knife, and not more than

an inch and a half long. If you will examine the top of the cork, you will observe that

the screw was driven in three times before the cork was extracted. It has never been [642] transfixed. This long screw

would have transfixed it and drawn it up with a single pull. When you catch this fellow,

you will find that he has one of these multiplex knives in his possession.”

“Excellent!” said Hopkins. “Excellent!” said Hopkins.

“But these glasses do puzzle me, I confess. Lady

Brackenstall actually saw the three men drinking, did she not?” “But these glasses do puzzle me, I confess. Lady

Brackenstall actually saw the three men drinking, did she not?”

“Yes; she was clear about that.” “Yes; she was clear about that.”

“Then there is an end of it. What more is to be said? And

yet, you must admit, that the three glasses are very remarkable, Hopkins. What? You see

nothing remarkable? Well, well, let it pass. Perhaps, when a man has special knowledge and

special powers like my own, it rather encourages him to seek a complex explanation when a

simpler one is at hand. Of course, it must be a mere chance about the glasses. Well,

good-morning, Hopkins. I don’t see that I can be of any use to you, and you appear to

have your case very clear. You will let me know when Randall is arrested, and any further

developments which may occur. I trust that I shall soon have to congratulate you upon a

successful conclusion. Come, Watson, I fancy that we may employ ourselves more profitably

at home.” “Then there is an end of it. What more is to be said? And

yet, you must admit, that the three glasses are very remarkable, Hopkins. What? You see

nothing remarkable? Well, well, let it pass. Perhaps, when a man has special knowledge and

special powers like my own, it rather encourages him to seek a complex explanation when a

simpler one is at hand. Of course, it must be a mere chance about the glasses. Well,

good-morning, Hopkins. I don’t see that I can be of any use to you, and you appear to

have your case very clear. You will let me know when Randall is arrested, and any further

developments which may occur. I trust that I shall soon have to congratulate you upon a

successful conclusion. Come, Watson, I fancy that we may employ ourselves more profitably

at home.”

During our return journey, I could see by Holmes’s

face that he was much puzzled by something which he had observed. Every now and then, by

an effort, he would throw off the impression, and talk as if the matter were clear, but

then his doubts would settle down upon him again, and his knitted brows and abstracted

eyes would show that his thoughts had gone back once more to the great dining-room of the

Abbey Grange, in which this midnight tragedy had been enacted. At last, by a sudden

impulse, just as our train was crawling out of a suburban station, he sprang on to the

platform and pulled me out after him. During our return journey, I could see by Holmes’s

face that he was much puzzled by something which he had observed. Every now and then, by

an effort, he would throw off the impression, and talk as if the matter were clear, but

then his doubts would settle down upon him again, and his knitted brows and abstracted

eyes would show that his thoughts had gone back once more to the great dining-room of the

Abbey Grange, in which this midnight tragedy had been enacted. At last, by a sudden

impulse, just as our train was crawling out of a suburban station, he sprang on to the

platform and pulled me out after him.

“Excuse me, my dear fellow,” said he, as we watched

the rear carriages of our train disappearing round a curve, “I am sorry to make you

the victim of what may seem a mere whim, but on my life, Watson, I simply can’t

leave that case in this condition. Every instinct that I possess cries out against it.

It’s wrong –it’s all wrong–I’ll swear that it’s wrong. And

yet the lady’s story was complete, the maid’s corroboration was sufficient, the

detail was fairly exact. What have I to put up against that? Three wine-glasses, that is

all. But if I had not taken things for granted, if I had examined everything with care

which I should have shown had we approached the case de novo and had no cut-and-dried

story to warp my mind, should I not then have found something more definite to go upon? Of

course I should. Sit down on this bench, Watson, until a train for Chiselhurst arrives,

and allow me to lay the evidence before you, imploring you in the first instance to

dismiss from your mind the idea that anything which the maid or her mistress may have said

must necessarily be true. The lady’s charming personality must not be permitted to

warp our judgment. “Excuse me, my dear fellow,” said he, as we watched

the rear carriages of our train disappearing round a curve, “I am sorry to make you

the victim of what may seem a mere whim, but on my life, Watson, I simply can’t

leave that case in this condition. Every instinct that I possess cries out against it.

It’s wrong –it’s all wrong–I’ll swear that it’s wrong. And

yet the lady’s story was complete, the maid’s corroboration was sufficient, the

detail was fairly exact. What have I to put up against that? Three wine-glasses, that is

all. But if I had not taken things for granted, if I had examined everything with care

which I should have shown had we approached the case de novo and had no cut-and-dried

story to warp my mind, should I not then have found something more definite to go upon? Of

course I should. Sit down on this bench, Watson, until a train for Chiselhurst arrives,

and allow me to lay the evidence before you, imploring you in the first instance to

dismiss from your mind the idea that anything which the maid or her mistress may have said

must necessarily be true. The lady’s charming personality must not be permitted to

warp our judgment.

“Surely there are details in her story which, if we

looked at in cold blood, would excite our suspicion. These burglars made a considerable

haul at Sydenham a fortnight ago. Some account of them and of their appearance was in the

papers, and would naturally occur to anyone who wished to invent a story in which

imaginary robbers should play a part. As a matter of fact, burglars who have done a good

stroke of business are, as a rule, only too glad to enjoy the proceeds in peace and quiet

without embarking on another perilous undertaking. Again, it is unusual for burglars to

operate at so early an hour, it is unusual for burglars to strike a lady to prevent her

screaming, since one would imagine that was the sure way to make her [643] scream, it is unusual for them to commit murder when

their numbers are sufficient to overpower one man, it is unusual for them to be content

with a limited plunder when there was much more within their reach, and finally, I should

say, that it was very unusual for such men to leave a bottle half empty. How do all these

unusuals strike you, Watson?” “Surely there are details in her story which, if we

looked at in cold blood, would excite our suspicion. These burglars made a considerable

haul at Sydenham a fortnight ago. Some account of them and of their appearance was in the

papers, and would naturally occur to anyone who wished to invent a story in which

imaginary robbers should play a part. As a matter of fact, burglars who have done a good

stroke of business are, as a rule, only too glad to enjoy the proceeds in peace and quiet

without embarking on another perilous undertaking. Again, it is unusual for burglars to

operate at so early an hour, it is unusual for burglars to strike a lady to prevent her

screaming, since one would imagine that was the sure way to make her [643] scream, it is unusual for them to commit murder when

their numbers are sufficient to overpower one man, it is unusual for them to be content

with a limited plunder when there was much more within their reach, and finally, I should

say, that it was very unusual for such men to leave a bottle half empty. How do all these

unusuals strike you, Watson?”

“Their cumulative effect is certainly considerable, and

yet each of them is quite possible in itself. The most unusual thing of all, as it seems

to me, is that the lady should be tied to the chair.” “Their cumulative effect is certainly considerable, and

yet each of them is quite possible in itself. The most unusual thing of all, as it seems

to me, is that the lady should be tied to the chair.”

“Well, I am not so clear about that, Watson, for it is

evident that they must either kill her or else secure her in such a way that she could not

give immediate notice of their escape. But at any rate I have shown, have I not, that

there is a certain element of improbability about the lady’s story? And now, on the

top of this, comes the incident of the wineglasses.” “Well, I am not so clear about that, Watson, for it is

evident that they must either kill her or else secure her in such a way that she could not

give immediate notice of their escape. But at any rate I have shown, have I not, that

there is a certain element of improbability about the lady’s story? And now, on the

top of this, comes the incident of the wineglasses.”

“What about the wineglasses?” “What about the wineglasses?”

“Can you see them in your mind’s eye?” “Can you see them in your mind’s eye?”

“I see them clearly.” “I see them clearly.”

“We are told that three men drank from them. Does that

strike you as likely?” “We are told that three men drank from them. Does that

strike you as likely?”

“Why not? There was wine in each glass.” “Why not? There was wine in each glass.”

“Exactly, but there was beeswing only in one glass. You

must have noticed that fact. What does that suggest to your mind?” “Exactly, but there was beeswing only in one glass. You

must have noticed that fact. What does that suggest to your mind?”

“The last glass filled would be most likely to contain

beeswing.” “The last glass filled would be most likely to contain

beeswing.”

“Not at all. The bottle was full of it, and it is

inconceivable that the first two glasses were clear and the third heavily charged with it.

There are two possible explanations, and only two. One is that after the second glass was

filled the bottle was violently agitated, and so the third glass received the beeswing.

That does not appear probable. No, no, I am sure that I am right.” “Not at all. The bottle was full of it, and it is

inconceivable that the first two glasses were clear and the third heavily charged with it.

There are two possible explanations, and only two. One is that after the second glass was

filled the bottle was violently agitated, and so the third glass received the beeswing.

That does not appear probable. No, no, I am sure that I am right.”

“What, then, do you suppose?” “What, then, do you suppose?”

“That only two glasses were used, and that the dregs of

both were poured into a third glass, so as to give the false impression that three people

had been here. In that way all the beeswing would be in the last glass, would it not? Yes,

I am convinced that this is so. But if I have hit upon the true explanation of this one

small phenomenon, then in an instant the case rises from the commonplace to the

exceedingly remarkable, for it can only mean that Lady Brackenstall and her maid have

deliberately lied to us, that not one word of their story is to be believed, that they

have some very strong reason for covering the real criminal, and that we must construct

our case for ourselves without any help from them. That is the mission which now lies

before us, and here, Watson, is the Sydenham train.” “That only two glasses were used, and that the dregs of

both were poured into a third glass, so as to give the false impression that three people

had been here. In that way all the beeswing would be in the last glass, would it not? Yes,

I am convinced that this is so. But if I have hit upon the true explanation of this one

small phenomenon, then in an instant the case rises from the commonplace to the

exceedingly remarkable, for it can only mean that Lady Brackenstall and her maid have

deliberately lied to us, that not one word of their story is to be believed, that they

have some very strong reason for covering the real criminal, and that we must construct

our case for ourselves without any help from them. That is the mission which now lies

before us, and here, Watson, is the Sydenham train.”

The household at the Abbey Grange were much surprised at our

return, but Sherlock Holmes, finding that Stanley Hopkins had gone off to report to

headquarters, took possession of the dining-room, locked the door upon the inside, and

devoted himself for two hours to one of those minute and laborious investigations which

form the solid basis on which his brilliant edifices of deduction were reared. Seated in a

corner like an interested student who observes the demonstration of his professor, I

followed every step of that remarkable research. The window, the curtains, the carpet, the

chair, the rope –each in turn was minutely examined and duly pondered. The body of

the unfortunate baronet had been removed, and all else remained as we had seen it in the

morning. Finally, to my astonishment, Holmes climbed up on to the massive mantelpiece. Far

above his head hung the few inches of red cord which were still attached to the wire. For

a long time he [644] gazed

upward at it, and then in an attempt to get nearer to it he rested his knee upon a wooden

bracket on the wall. This brought his hand within a few inches of the broken end of the

rope, but it was not this so much as the bracket itself which seemed to engage his

attention. Finally, he sprang down with an ejaculation of satisfaction. The household at the Abbey Grange were much surprised at our

return, but Sherlock Holmes, finding that Stanley Hopkins had gone off to report to

headquarters, took possession of the dining-room, locked the door upon the inside, and

devoted himself for two hours to one of those minute and laborious investigations which

form the solid basis on which his brilliant edifices of deduction were reared. Seated in a

corner like an interested student who observes the demonstration of his professor, I

followed every step of that remarkable research. The window, the curtains, the carpet, the

chair, the rope –each in turn was minutely examined and duly pondered. The body of

the unfortunate baronet had been removed, and all else remained as we had seen it in the

morning. Finally, to my astonishment, Holmes climbed up on to the massive mantelpiece. Far

above his head hung the few inches of red cord which were still attached to the wire. For

a long time he [644] gazed

upward at it, and then in an attempt to get nearer to it he rested his knee upon a wooden

bracket on the wall. This brought his hand within a few inches of the broken end of the

rope, but it was not this so much as the bracket itself which seemed to engage his

attention. Finally, he sprang down with an ejaculation of satisfaction.

“It’s all right, Watson,” said he. “We

have got our case–one of the most remarkable in our collection. But, dear me, how

slow-witted I have been, and how nearly I have committed the blunder of my lifetime! Now,

I think that, with a few missing links, my chain is almost complete.” “It’s all right, Watson,” said he. “We

have got our case–one of the most remarkable in our collection. But, dear me, how

slow-witted I have been, and how nearly I have committed the blunder of my lifetime! Now,

I think that, with a few missing links, my chain is almost complete.”

“You have got your men?” “You have got your men?”

“Man, Watson, man. Only one, but a very formidable

person. Strong as a lion–witness the blow that bent that poker! Six foot three in

height, active as a squirrel, dexterous with his fingers, finally, remarkably

quick-witted, for this whole ingenious story is of his concoction. Yes, Watson, we have

come upon the handiwork of a very remarkable individual. And yet, in that bell-rope, he

has given us a clue which should not have left us a doubt.” “Man, Watson, man. Only one, but a very formidable

person. Strong as a lion–witness the blow that bent that poker! Six foot three in

height, active as a squirrel, dexterous with his fingers, finally, remarkably

quick-witted, for this whole ingenious story is of his concoction. Yes, Watson, we have

come upon the handiwork of a very remarkable individual. And yet, in that bell-rope, he

has given us a clue which should not have left us a doubt.”

“Where was the clue?” “Where was the clue?”

“Well, if you were to pull down a bell-rope, Watson,

where would you expect it to break? Surely at the spot where it is attached to the wire.

Why should it break three inches from the top, as this one has done?” “Well, if you were to pull down a bell-rope, Watson,

where would you expect it to break? Surely at the spot where it is attached to the wire.

Why should it break three inches from the top, as this one has done?”

“Because it is frayed there?” “Because it is frayed there?”

“Exactly. This end, which we can examine, is frayed. He

was cunning enough to do that with his knife. But the other end is not frayed. You could

not observe that from here, but if you were on the mantelpiece you would see that it is

cut clean off without any mark of fraying whatever. You can reconstruct what occurred. The

man needed the rope. He would not tear it down for fear of giving the alarm by ringing the

bell. What did he do? He sprang up on the mantelpiece, could not quite reach it, put his

knee on the bracket–you will see the impression in the dust–and so got his knife

to bear upon the cord. I could not reach the place by at least three inches–from

which I infer that he is at least three inches a bigger man than I. Look at that mark upon

the seat of the oaken chair! What is it?” “Exactly. This end, which we can examine, is frayed. He

was cunning enough to do that with his knife. But the other end is not frayed. You could

not observe that from here, but if you were on the mantelpiece you would see that it is

cut clean off without any mark of fraying whatever. You can reconstruct what occurred. The

man needed the rope. He would not tear it down for fear of giving the alarm by ringing the

bell. What did he do? He sprang up on the mantelpiece, could not quite reach it, put his

knee on the bracket–you will see the impression in the dust–and so got his knife

to bear upon the cord. I could not reach the place by at least three inches–from

which I infer that he is at least three inches a bigger man than I. Look at that mark upon

the seat of the oaken chair! What is it?”

“Blood.” “Blood.”

“Undoubtedly it is blood. This alone puts the lady’s

story out of court. If she were seated on the chair when the crime was done, how comes

that mark? No, no, she was placed in the chair after the death of her husband.

I’ll wager that the black dress shows a corresponding mark to this. We have not yet

met our Waterloo, Watson, but this is our Marengo, for it begins in defeat and ends in

victory. I should like now to have a few words with the nurse, Theresa. We must be wary

for a while, if we are to get the information which we want.” “Undoubtedly it is blood. This alone puts the lady’s

story out of court. If she were seated on the chair when the crime was done, how comes

that mark? No, no, she was placed in the chair after the death of her husband.

I’ll wager that the black dress shows a corresponding mark to this. We have not yet

met our Waterloo, Watson, but this is our Marengo, for it begins in defeat and ends in

victory. I should like now to have a few words with the nurse, Theresa. We must be wary

for a while, if we are to get the information which we want.”

She was an interesting person, this stern Australian

nurse–taciturn, suspicious, ungracious, it took some time before Holmes’s

pleasant manner and frank acceptance of all that she said thawed her into a corresponding

amiability. She did not attempt to conceal her hatred for her late employer. She was an interesting person, this stern Australian

nurse–taciturn, suspicious, ungracious, it took some time before Holmes’s

pleasant manner and frank acceptance of all that she said thawed her into a corresponding

amiability. She did not attempt to conceal her hatred for her late employer.

“Yes, sir, it is true that he threw the decanter at me. I

heard him call my mistress a name, and I told him that he would not dare to speak so if

her brother had been there. Then it was that he threw it at me. He might have thrown a

dozen if he had but left my bonny bird alone. He was forever ill-treating her, and she too

proud to complain. She will not even tell me all that he has done to her. She never told

me of those marks on her arm that you saw this morning, but I know very well [645] that they come from a stab

with a hatpin. The sly devil–God forgive me that I should speak of him so, now that

he is dead! But a devil he was, if ever one walked the earth. He was all honey when first

we met him–only eighteen months ago, and we both feel as if it were eighteen years.

She had only just arrived in London. Yes, it was her first voyage–she had never been

from home before. He won her with his title and his money and his false London ways. If

she made a mistake she has paid for it, if ever a woman did. What month did we meet him?

Well, I tell you it was just after we arrived. We arrived in June, and it was July. They

were married in January of last year. Yes, she is down in the morning-room again, and I

have no doubt she will see you, but you must not ask too much of her, for she has gone

through all that flesh and blood will stand.” “Yes, sir, it is true that he threw the decanter at me. I

heard him call my mistress a name, and I told him that he would not dare to speak so if

her brother had been there. Then it was that he threw it at me. He might have thrown a

dozen if he had but left my bonny bird alone. He was forever ill-treating her, and she too

proud to complain. She will not even tell me all that he has done to her. She never told

me of those marks on her arm that you saw this morning, but I know very well [645] that they come from a stab

with a hatpin. The sly devil–God forgive me that I should speak of him so, now that

he is dead! But a devil he was, if ever one walked the earth. He was all honey when first

we met him–only eighteen months ago, and we both feel as if it were eighteen years.

She had only just arrived in London. Yes, it was her first voyage–she had never been

from home before. He won her with his title and his money and his false London ways. If

she made a mistake she has paid for it, if ever a woman did. What month did we meet him?

Well, I tell you it was just after we arrived. We arrived in June, and it was July. They

were married in January of last year. Yes, she is down in the morning-room again, and I

have no doubt she will see you, but you must not ask too much of her, for she has gone

through all that flesh and blood will stand.”

Lady Brackenstall was reclining on the same couch, but looked

brighter than before. The maid had entered with us, and began once more to foment the

bruise upon her mistress’s brow. Lady Brackenstall was reclining on the same couch, but looked

brighter than before. The maid had entered with us, and began once more to foment the

bruise upon her mistress’s brow.

“I hope,” said the lady, “that you have not

come to cross-examine me again?” “I hope,” said the lady, “that you have not

come to cross-examine me again?”

“No,” Holmes answered, in his gentlest voice,

“I will not cause you any unnecessary trouble, Lady Brackenstall, and my whole desire

is to make things easy for you, for I am convinced that you are a much-tried woman. If you

will treat me as a friend and trust me, you may find that I will justify your trust.” “No,” Holmes answered, in his gentlest voice,

“I will not cause you any unnecessary trouble, Lady Brackenstall, and my whole desire

is to make things easy for you, for I am convinced that you are a much-tried woman. If you

will treat me as a friend and trust me, you may find that I will justify your trust.”

“What do you want me to do?” “What do you want me to do?”

“To tell me the truth.” “To tell me the truth.”

“Mr. Holmes!” “Mr. Holmes!”

“No, no, Lady Brackenstall–it is no use. You may

have heard of any little reputation which I possess. I will stake it all on the fact that

your story is an absolute fabrication.” “No, no, Lady Brackenstall–it is no use. You may

have heard of any little reputation which I possess. I will stake it all on the fact that

your story is an absolute fabrication.”

Mistress and maid were both staring at Holmes with pale faces

and frightened eyes. Mistress and maid were both staring at Holmes with pale faces

and frightened eyes.

“You are an impudent fellow!” cried Theresa.

“Do you mean to say that my mistress has told a lie?” “You are an impudent fellow!” cried Theresa.

“Do you mean to say that my mistress has told a lie?”

Holmes rose from his chair. Holmes rose from his chair.

“Have you nothing to tell me?” “Have you nothing to tell me?”

“I have told you everything.” “I have told you everything.”

“Think once more, Lady Brackenstall. Would it not be

better to be frank?” “Think once more, Lady Brackenstall. Would it not be

better to be frank?”

For an instant there was hesitation in her beautiful face.

Then some new strong thought caused it to set like a mask. For an instant there was hesitation in her beautiful face.

Then some new strong thought caused it to set like a mask.

“I have told you all I know.” “I have told you all I know.”

Holmes took his hat and shrugged his shoulders. “I am

sorry,” he said, and without another word we left the room and the house. There was a

pond in the park, and to this my friend led the way. It was frozen over, but a single hole

was left for the convenience of a solitary swan. Holmes gazed at it, and then passed on to

the lodge gate. There he scribbled a short note for Stanley Hopkins, and left it with the

lodge-keeper. Holmes took his hat and shrugged his shoulders. “I am

sorry,” he said, and without another word we left the room and the house. There was a

pond in the park, and to this my friend led the way. It was frozen over, but a single hole

was left for the convenience of a solitary swan. Holmes gazed at it, and then passed on to

the lodge gate. There he scribbled a short note for Stanley Hopkins, and left it with the

lodge-keeper.

“It may be a hit, or it may be a miss, but we are

bound to do something for friend Hopkins, just to justify this second visit,” said

he. “I will not quite take him into my confidence yet. I think our next scene of

operations must be the shipping office of the Adelaide-Southampton line, which stands at

the end of Pall Mall, if I remember right. There is a second line of steamers which

connect South Australia with England, but we will draw the larger cover first.” “It may be a hit, or it may be a miss, but we are

bound to do something for friend Hopkins, just to justify this second visit,” said

he. “I will not quite take him into my confidence yet. I think our next scene of

operations must be the shipping office of the Adelaide-Southampton line, which stands at

the end of Pall Mall, if I remember right. There is a second line of steamers which

connect South Australia with England, but we will draw the larger cover first.”

Holmes’s card sent in to the manager ensured instant

attention, and he was [646] not

long in acquiring all the information he needed. In June of ’95, only one of their

line had reached a home port. It was the Rock of Gibraltar, their largest and

best boat. A reference to the passenger list showed that Miss Fraser, of Adelaide, with

her maid had made the voyage in her. The boat was now somewhere south of the Suez Canal on

her way to Australia. Her officers were the same as in ’95, with one exception. The

first officer, Mr. Jack Crocker, had been made a captain and was to take charge of their

new ship, the Bass Rock, sailing in two days’ time from Southampton. He

lived at Sydenham, but he was likely to be in that morning for instructions, if we cared

to wait for him. Holmes’s card sent in to the manager ensured instant

attention, and he was [646] not

long in acquiring all the information he needed. In June of ’95, only one of their

line had reached a home port. It was the Rock of Gibraltar, their largest and

best boat. A reference to the passenger list showed that Miss Fraser, of Adelaide, with

her maid had made the voyage in her. The boat was now somewhere south of the Suez Canal on

her way to Australia. Her officers were the same as in ’95, with one exception. The

first officer, Mr. Jack Crocker, had been made a captain and was to take charge of their

new ship, the Bass Rock, sailing in two days’ time from Southampton. He

lived at Sydenham, but he was likely to be in that morning for instructions, if we cared

to wait for him.

No, Mr. Holmes had no desire to see him, but would be glad to

know more about his record and character. No, Mr. Holmes had no desire to see him, but would be glad to

know more about his record and character.

His record was magnificent. There was not an officer in the

fleet to touch him. As to his character, he was reliable on duty, but a wild, desperate

fellow off the deck of his ship–hot-headed, excitable, but loyal, honest, and

kind-hearted. That was the pith of the information with which Holmes left the office of

the Adelaide-Southampton company. Thence he drove to Scotland Yard, but, instead of

entering, he sat in his cab with his brows drawn down, lost in profound thought. Finally

he drove round to the Charing Cross telegraph office, sent off a message, and then, at

last, we made for Baker Street once more. His record was magnificent. There was not an officer in the

fleet to touch him. As to his character, he was reliable on duty, but a wild, desperate

fellow off the deck of his ship–hot-headed, excitable, but loyal, honest, and

kind-hearted. That was the pith of the information with which Holmes left the office of

the Adelaide-Southampton company. Thence he drove to Scotland Yard, but, instead of

entering, he sat in his cab with his brows drawn down, lost in profound thought. Finally

he drove round to the Charing Cross telegraph office, sent off a message, and then, at

last, we made for Baker Street once more.

“No, I couldn’t do it, Watson,” said he, as we

reentered our room. “Once that warrant was made out, nothing on earth would save him.

Once or twice in my career I feel that I have done more real harm by my discovery of the

criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather

play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience. Let us know a little more

before we act.” “No, I couldn’t do it, Watson,” said he, as we

reentered our room. “Once that warrant was made out, nothing on earth would save him.

Once or twice in my career I feel that I have done more real harm by my discovery of the

criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather

play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience. Let us know a little more

before we act.”

Before evening, we had a visit from Inspector Stanley Hopkins.

Things were not going very well with him. Before evening, we had a visit from Inspector Stanley Hopkins.

Things were not going very well with him.

“I believe that you are a wizard, Mr. Holmes. I really do

sometimes think that you have powers that are not human. Now, how on earth could you know

that the stolen silver was at the bottom of that pond?” “I believe that you are a wizard, Mr. Holmes. I really do

sometimes think that you have powers that are not human. Now, how on earth could you know

that the stolen silver was at the bottom of that pond?”

“I didn’t know it.” “I didn’t know it.”

“But you told me to examine it.” “But you told me to examine it.”

“You got it, then?” “You got it, then?”

“Yes, I got it.” “Yes, I got it.”

“I am very glad if I have helped you.” “I am very glad if I have helped you.”

“But you haven’t helped me. You have made the affair

far more difficult. What sort of burglars are they who steal silver and then throw it into

the nearest pond?” “But you haven’t helped me. You have made the affair

far more difficult. What sort of burglars are they who steal silver and then throw it into

the nearest pond?”

“It was certainly rather eccentric behaviour. I was

merely going on the idea that if the silver had been taken by persons who did not want

it–who merely took it for a blind, as it were–then they would naturally be

anxious to get rid of it.” “It was certainly rather eccentric behaviour. I was

merely going on the idea that if the silver had been taken by persons who did not want

it–who merely took it for a blind, as it were–then they would naturally be

anxious to get rid of it.”

“But why should such an idea cross your mind?” “But why should such an idea cross your mind?”

“Well, I thought it was possible. When they came out

through the French window, there was the pond with one tempting little hole in the ice,

right in front of their noses. Could there be a better hiding-place?” “Well, I thought it was possible. When they came out

through the French window, there was the pond with one tempting little hole in the ice,

right in front of their noses. Could there be a better hiding-place?”

“Ah, a hiding-place–that is better!” cried

Stanley Hopkins. “Yes, yes, I see it all now! It was early, there were folk upon the

roads, they were afraid of being seen with the silver, so they sank it in the pond,

intending to return for it when the coast was clear. Excellent, Mr. Holmes–that is

better than your idea of a blind.” “Ah, a hiding-place–that is better!” cried

Stanley Hopkins. “Yes, yes, I see it all now! It was early, there were folk upon the

roads, they were afraid of being seen with the silver, so they sank it in the pond,

intending to return for it when the coast was clear. Excellent, Mr. Holmes–that is

better than your idea of a blind.”

“Quite so, you have got an admirable theory. I have no

doubt that my own ideas [647] were

quite wild, but you must admit that they have ended in discovering the silver.” “Quite so, you have got an admirable theory. I have no

doubt that my own ideas [647] were

quite wild, but you must admit that they have ended in discovering the silver.”

“Yes, sir–yes. It was all your doing. But I have had

a bad setback.” “Yes, sir–yes. It was all your doing. But I have had

a bad setback.”

“A setback?” “A setback?”

“Yes, Mr. Holmes. The Randall gang were arrested in New

York this morning.” “Yes, Mr. Holmes. The Randall gang were arrested in New

York this morning.”

“Dear me, Hopkins! That is certainly rather against your

theory that they committed a murder in Kent last night.” “Dear me, Hopkins! That is certainly rather against your

theory that they committed a murder in Kent last night.”

“It is fatal, Mr. Holmes–absolutely fatal. Still,

there are other gangs of three besides the Randalls, or it may be some new gang of which

the police have never heard.” “It is fatal, Mr. Holmes–absolutely fatal. Still,

there are other gangs of three besides the Randalls, or it may be some new gang of which

the police have never heard.”

“Quite so, it is perfectly possible. What, are you

off?” “Quite so, it is perfectly possible. What, are you

off?”

“Yes, Mr. Holmes, there is no rest for me until I have

got to the bottom of the business. I suppose you have no hint to give me?” “Yes, Mr. Holmes, there is no rest for me until I have

got to the bottom of the business. I suppose you have no hint to give me?”

“I have given you one.” “I have given you one.”

“Which?” “Which?”

“Well, I suggested a blind.” “Well, I suggested a blind.”

“But why, Mr. Holmes, why?” “But why, Mr. Holmes, why?”

“Ah, that’s the question, of course. But I commend

the idea to your mind. You might possibly find that there was something in it. You

won’t stop for dinner? Well, good-bye, and let us know how you get on.” “Ah, that’s the question, of course. But I commend

the idea to your mind. You might possibly find that there was something in it. You

won’t stop for dinner? Well, good-bye, and let us know how you get on.”

Dinner was over, and the table cleared before Holmes alluded

to the matter again. He had lit his pipe and held his slippered feet to the cheerful blaze

of the fire. Suddenly he looked at his watch. Dinner was over, and the table cleared before Holmes alluded

to the matter again. He had lit his pipe and held his slippered feet to the cheerful blaze

of the fire. Suddenly he looked at his watch.

“I expect developments, Watson.” “I expect developments, Watson.”

“When?” “When?”

“Now–within a few minutes. I dare say you thought I

acted rather badly to Stanley Hopkins just now?” “Now–within a few minutes. I dare say you thought I

acted rather badly to Stanley Hopkins just now?”

“I trust your judgment.” “I trust your judgment.”

“A very sensible reply, Watson. You must look at it this

way: what I know is unofficial, what he knows is official. I have the right to private

judgment, but he has none. He must disclose all, or he is a traitor to his service. In a

doubtful case I would not put him in so painful a position, and so I reserve my

information until my own mind is clear upon the matter.” “A very sensible reply, Watson. You must look at it this

way: what I know is unofficial, what he knows is official. I have the right to private

judgment, but he has none. He must disclose all, or he is a traitor to his service. In a

doubtful case I would not put him in so painful a position, and so I reserve my

information until my own mind is clear upon the matter.”

“But when will that be?” “But when will that be?”

“The time has come. You will now be present at the last

scene of a remarkable little drama.” “The time has come. You will now be present at the last

scene of a remarkable little drama.”

There was a sound upon the stairs, and our door was opened

to admit as fine a specimen of manhood as ever passed through it. He was a very tall young

man, golden-moustached, blue-eyed, with a skin which had been burned by tropical suns, and

a springy step, which showed that the huge frame was as active as it was strong. He closed

the door behind him, and then he stood with clenched hands and heaving breast, choking

down some overmastering emotion. There was a sound upon the stairs, and our door was opened

to admit as fine a specimen of manhood as ever passed through it. He was a very tall young

man, golden-moustached, blue-eyed, with a skin which had been burned by tropical suns, and

a springy step, which showed that the huge frame was as active as it was strong. He closed

the door behind him, and then he stood with clenched hands and heaving breast, choking

down some overmastering emotion.

“Sit down, Captain Crocker. You got my telegram?” “Sit down, Captain Crocker. You got my telegram?”

Our visitor sank into an armchair and looked from one to the

other of us with questioning eyes. Our visitor sank into an armchair and looked from one to the

other of us with questioning eyes.

“I got your telegram, and I came at the hour you said. I

heard that you had been down to the office. There was no getting away from you. Let’s

hear the worst. What are you going to do with me? Arrest me? Speak out, man! You

can’t sit there and play with me like a cat with a mouse.” “I got your telegram, and I came at the hour you said. I

heard that you had been down to the office. There was no getting away from you. Let’s

hear the worst. What are you going to do with me? Arrest me? Speak out, man! You

can’t sit there and play with me like a cat with a mouse.”

[648] “Give

him a cigar,” said Holmes. “Bite on that, Captain Crocker, and don’t let

your nerves run away with you. I should not sit here smoking with you if I thought that

you were a common criminal, you may be sure of that. Be frank with me and we may do some

good. Play tricks with me, and I’ll crush you.” [648] “Give

him a cigar,” said Holmes. “Bite on that, Captain Crocker, and don’t let

your nerves run away with you. I should not sit here smoking with you if I thought that

you were a common criminal, you may be sure of that. Be frank with me and we may do some

good. Play tricks with me, and I’ll crush you.”

“What do you wish me to do?” “What do you wish me to do?”

“To give me a true account of all that happened at the

Abbey Grange last night–a true account, mind you, with nothing added and

nothing taken off. I know so much already that if you go one inch off the straight,

I’ll blow this police whistle from my window and the affair goes out of my hands

forever.” “To give me a true account of all that happened at the

Abbey Grange last night–a true account, mind you, with nothing added and

nothing taken off. I know so much already that if you go one inch off the straight,

I’ll blow this police whistle from my window and the affair goes out of my hands

forever.”

The sailor thought for a little. Then he struck his leg with

his great sunburned hand. The sailor thought for a little. Then he struck his leg with

his great sunburned hand.

“I’ll chance it,” he cried. “I believe you

are a man of your word, and a white man, and I’ll tell you the whole story. But one

thing I will say first. So far as I am concerned, I regret nothing and I fear nothing, and

I would do it all again and be proud of the job. Damn the beast, if he had as many lives

as a cat, he would owe them all to me! But it’s the lady, Mary–Mary

Fraser–for never will I call her by that accursed name. When I think of getting her

into trouble, I who would give my life just to bring one smile to her dear face, it’s

that that turns my soul into water. And yet–and yet–what less could I do?

I’ll tell you my story, gentlemen, and then I’ll ask you, as man to man, what

less could I do? “I’ll chance it,” he cried. “I believe you

are a man of your word, and a white man, and I’ll tell you the whole story. But one

thing I will say first. So far as I am concerned, I regret nothing and I fear nothing, and

I would do it all again and be proud of the job. Damn the beast, if he had as many lives

as a cat, he would owe them all to me! But it’s the lady, Mary–Mary

Fraser–for never will I call her by that accursed name. When I think of getting her

into trouble, I who would give my life just to bring one smile to her dear face, it’s

that that turns my soul into water. And yet–and yet–what less could I do?

I’ll tell you my story, gentlemen, and then I’ll ask you, as man to man, what

less could I do?

“I must go back a bit. You seem to know everything, so I

expect that you know that I met her when she was a passenger and I was first officer of

the Rock of Gibraltar. From the first day I met her, she was the only woman to

me. Every day of that voyage I loved her more, and many a time since have I kneeled down

in the darkness of the night watch and kissed the deck of that ship because I knew her

dear feet had trod it. She was never engaged to me. She treated me as fairly as ever a

woman treated a man. I have no complaint to make. It was all love on my side, and all good

comradeship and friendship on hers. When we parted she was a free woman, but I could never

again be a free man. “I must go back a bit. You seem to know everything, so I

expect that you know that I met her when she was a passenger and I was first officer of

the Rock of Gibraltar. From the first day I met her, she was the only woman to

me. Every day of that voyage I loved her more, and many a time since have I kneeled down

in the darkness of the night watch and kissed the deck of that ship because I knew her

dear feet had trod it. She was never engaged to me. She treated me as fairly as ever a

woman treated a man. I have no complaint to make. It was all love on my side, and all good

comradeship and friendship on hers. When we parted she was a free woman, but I could never

again be a free man.

“Next time I came back from sea, I heard of her marriage.

Well, why shouldn’t she marry whom she liked? Title and money–who could carry

them better than she? She was born for all that is beautiful and dainty. I didn’t

grieve over her marriage. I was not such a selfish hound as that. I just rejoiced that

good luck had come her way, and that she had not thrown herself away on a penniless

sailor. That’s how I loved Mary Fraser. “Next time I came back from sea, I heard of her marriage.

Well, why shouldn’t she marry whom she liked? Title and money–who could carry

them better than she? She was born for all that is beautiful and dainty. I didn’t

grieve over her marriage. I was not such a selfish hound as that. I just rejoiced that

good luck had come her way, and that she had not thrown herself away on a penniless

sailor. That’s how I loved Mary Fraser.

“Well, I never thought to see her again, but last voyage

I was promoted, and the new boat was not yet launched, so I had to wait for a couple of

months with my people at Sydenham. One day out in a country lane I met Theresa Wright, her

old maid. She told me all about her, about him, about everything. I tell you, gentlemen,

it nearly drove me mad. This drunken hound, that he should dare to raise his hand to her,

whose boots he was not worthy to lick! I met Theresa again. Then I met Mary

herself–and met her again. Then she would meet me no more. But the other day I had a

notice that I was to start on my voyage within a week, and I determined that I would see

her once before I left. Theresa was always my friend, for she loved Mary and hated this

villain almost as much as I did. From her I learned the ways of the house. Mary used to

sit up reading in her own little room downstairs. I crept round there last night and

scratched at the window. At first she would not open to me, but in her heart I know that

now she loves me, and she could not leave me in the frosty night. She whispered to me to

come [649] round to the big

front window, and I found it open before me, so as to let me into the dining-room. Again I

heard from her own lips things that made my blood boil, and again I cursed this brute who

mishandled the woman I loved. Well, gentlemen, I was standing with her just inside the

window, in all innocence, as God is my judge, when he rushed like a madman into the room,

called her the vilest name that a man could use to a woman, and welted her across the face

with the stick he had in his hand. I had sprung for the poker, and it was a fair fight

between us. See here, on my arm, where his first blow fell. Then it was my turn, and I

went through him as if he had been a rotten pumpkin. Do you think I was sorry? Not I! It

was his life or mine, but far more than that, it was his life or hers, for how could I

leave her in the power of this madman? That was how I killed him. Was I wrong? Well, then,

what would either of you gentlemen have done, if you had been in my position?” “Well, I never thought to see her again, but last voyage

I was promoted, and the new boat was not yet launched, so I had to wait for a couple of

months with my people at Sydenham. One day out in a country lane I met Theresa Wright, her

old maid. She told me all about her, about him, about everything. I tell you, gentlemen,