|

|

“Why, Mr. Holmes, I thought you knew things,” said

he. “I suppose, then, if you have never heard of Godfrey Staunton, you don’t

know Cyril Overton either?” “Why, Mr. Holmes, I thought you knew things,” said

he. “I suppose, then, if you have never heard of Godfrey Staunton, you don’t

know Cyril Overton either?”

Holmes shook his head good humouredly. Holmes shook his head good humouredly.

“Great Scott!” cried the athlete. “Why, I was

first reserve for England against Wales, and I’ve skippered the ’Varsity all

this year. But that’s nothing! I didn’t think there was a soul in England who

didn’t know Godfrey Staunton, the crack three-quarter, Cambridge, Blackheath, and

five Internationals. Good Lord! Mr. Holmes, where have you lived?” “Great Scott!” cried the athlete. “Why, I was

first reserve for England against Wales, and I’ve skippered the ’Varsity all

this year. But that’s nothing! I didn’t think there was a soul in England who

didn’t know Godfrey Staunton, the crack three-quarter, Cambridge, Blackheath, and

five Internationals. Good Lord! Mr. Holmes, where have you lived?”

Holmes laughed at the young giant’s naive astonishment. Holmes laughed at the young giant’s naive astonishment.

“You live in a different world to me, Mr. Overton–a

sweeter and healthier one. My ramifications stretch out into many sections of society, but

never, I am happy to say, into amateur sport, which is the best and soundest thing in

England. However, your unexpected visit this morning shows me that even in that world of

fresh air and fair play, there may be work for me to do. So now, my good sir, I beg you to

sit down and to tell me, slowly and quietly, exactly what it is that has occurred, and how

you desire that I should help you.” “You live in a different world to me, Mr. Overton–a

sweeter and healthier one. My ramifications stretch out into many sections of society, but

never, I am happy to say, into amateur sport, which is the best and soundest thing in

England. However, your unexpected visit this morning shows me that even in that world of

fresh air and fair play, there may be work for me to do. So now, my good sir, I beg you to

sit down and to tell me, slowly and quietly, exactly what it is that has occurred, and how

you desire that I should help you.”

Young Overton’s face assumed the bothered look of the man

who is more accustomed to using his muscles than his wits, but by degrees, with many

repetitions and obscurities which I may omit from his narrative, he laid his strange story

before us. Young Overton’s face assumed the bothered look of the man

who is more accustomed to using his muscles than his wits, but by degrees, with many

repetitions and obscurities which I may omit from his narrative, he laid his strange story

before us.

“It’s this way, Mr. Holmes. As I have said, I am the

skipper of the Rugger team of Cambridge ’Varsity, and Godfrey Staunton is my best

man. To-morrow we play Oxford. Yesterday we all came up, and we settled at Bentley’s

private hotel. At ten o’clock I went round and saw that all the fellows had gone to

roost, for I believe in strict training and plenty of sleep to keep a team fit. I had a

word or two with Godfrey before he turned in. He seemed to me to be pale and bothered. I

asked him what was the matter. He said he was all right –just a touch of headache. I

bade him good-night and left him. Half an hour later, the porter tells me that a

rough-looking man with a beard called with a note for Godfrey. He had not gone to bed, and

the note was taken to his room. Godfrey read it, and fell back in a chair as if he had

been pole-axed. The porter was so scared that he was going to fetch me, but Godfrey

stopped him, had a drink of water, and pulled himself together. Then he went downstairs,

said a few words to the man who was waiting in the hall, and the two of them went off

together. The last that the porter saw of them, they were almost running down the street

in the direction of the [624] Strand.

This morning Godfrey’s room was empty, his bed had never been slept in, and his

things were all just as I had seen them the night before. He had gone off at a

moment’s notice with this stranger, and no word has come from him since. I don’t

believe he will ever come back. He was a sportsman, was Godfrey, down to his marrow, and

he wouldn’t have stopped his training and let in his skipper if it were not for some

cause that was too strong for him. No: I feel as if he were gone for good, and we should

never see him again.” “It’s this way, Mr. Holmes. As I have said, I am the

skipper of the Rugger team of Cambridge ’Varsity, and Godfrey Staunton is my best

man. To-morrow we play Oxford. Yesterday we all came up, and we settled at Bentley’s

private hotel. At ten o’clock I went round and saw that all the fellows had gone to

roost, for I believe in strict training and plenty of sleep to keep a team fit. I had a

word or two with Godfrey before he turned in. He seemed to me to be pale and bothered. I

asked him what was the matter. He said he was all right –just a touch of headache. I

bade him good-night and left him. Half an hour later, the porter tells me that a

rough-looking man with a beard called with a note for Godfrey. He had not gone to bed, and

the note was taken to his room. Godfrey read it, and fell back in a chair as if he had

been pole-axed. The porter was so scared that he was going to fetch me, but Godfrey

stopped him, had a drink of water, and pulled himself together. Then he went downstairs,

said a few words to the man who was waiting in the hall, and the two of them went off

together. The last that the porter saw of them, they were almost running down the street

in the direction of the [624] Strand.

This morning Godfrey’s room was empty, his bed had never been slept in, and his

things were all just as I had seen them the night before. He had gone off at a

moment’s notice with this stranger, and no word has come from him since. I don’t

believe he will ever come back. He was a sportsman, was Godfrey, down to his marrow, and

he wouldn’t have stopped his training and let in his skipper if it were not for some

cause that was too strong for him. No: I feel as if he were gone for good, and we should

never see him again.”

Sherlock Holmes listened with the deepest attention to this

singular narrative. Sherlock Holmes listened with the deepest attention to this

singular narrative.

“What did you do?” he asked. “What did you do?” he asked.

“I wired to Cambridge to learn if anything had been heard

of him there. I have had an answer. No one has seen him.” “I wired to Cambridge to learn if anything had been heard

of him there. I have had an answer. No one has seen him.”

“Could he have got back to Cambridge?” “Could he have got back to Cambridge?”

“Yes, there is a late train–quarter-past

eleven.” “Yes, there is a late train–quarter-past

eleven.”

“But, so far as you can ascertain, he did not take

it?” “But, so far as you can ascertain, he did not take

it?”

“No, he has not been seen.” “No, he has not been seen.”

“What did you do next?” “What did you do next?”

“I wired to Lord Mount-James.” “I wired to Lord Mount-James.”

“Why to Lord Mount-James?” “Why to Lord Mount-James?”

“Godfrey is an orphan, and Lord Mount-James is his

nearest relative–his uncle, I believe.” “Godfrey is an orphan, and Lord Mount-James is his

nearest relative–his uncle, I believe.”

“Indeed. This throws new light upon the matter. Lord

Mount-James is one of the richest men in England.” “Indeed. This throws new light upon the matter. Lord

Mount-James is one of the richest men in England.”

“So I’ve heard Godfrey say.” “So I’ve heard Godfrey say.”

“And your friend was closely related?” “And your friend was closely related?”

“Yes, he was his heir, and the old boy is nearly

eighty–cram full of gout, too. They say he could chalk his billiard-cue with his

knuckles. He never allowed Godfrey a shilling in his life, for he is an absolute miser,

but it will all come to him right enough.” “Yes, he was his heir, and the old boy is nearly

eighty–cram full of gout, too. They say he could chalk his billiard-cue with his

knuckles. He never allowed Godfrey a shilling in his life, for he is an absolute miser,

but it will all come to him right enough.”

“Have you heard from Lord Mount-James?” “Have you heard from Lord Mount-James?”

“No.” “No.”

“What motive could your friend have in going to Lord

Mount-James?” “What motive could your friend have in going to Lord

Mount-James?”

“Well, something was worrying him the night before, and

if it was to do with money it is possible that he would make for his nearest relative, who

had so much of it, though from all I have heard he would not have much chance of getting

it. Godfrey was not fond of the old man. He would not go if he could help it.” “Well, something was worrying him the night before, and

if it was to do with money it is possible that he would make for his nearest relative, who

had so much of it, though from all I have heard he would not have much chance of getting

it. Godfrey was not fond of the old man. He would not go if he could help it.”

“Well, we can soon determine that. If your friend was

going to his relative, Lord Mount-James, you have then to explain the visit of this

rough-looking fellow at so late an hour, and the agitation that was caused by his

coming.” “Well, we can soon determine that. If your friend was

going to his relative, Lord Mount-James, you have then to explain the visit of this

rough-looking fellow at so late an hour, and the agitation that was caused by his

coming.”

Cyril Overton pressed his hands to his head. “I can make

nothing of it, ” said he. Cyril Overton pressed his hands to his head. “I can make

nothing of it, ” said he.

“Well, well, I have a clear day, and I shall be happy to

look into the matter,” said Holmes. “I should strongly recommend you to make

your preparations for your match without reference to this young gentleman. It must, as

you say, have been an overpowering necessity which tore him away in such a fashion, and

the same necessity is likely to hold him away. Let us step round together to the hotel,

and see if the porter can throw any fresh light upon the matter.” “Well, well, I have a clear day, and I shall be happy to

look into the matter,” said Holmes. “I should strongly recommend you to make

your preparations for your match without reference to this young gentleman. It must, as

you say, have been an overpowering necessity which tore him away in such a fashion, and

the same necessity is likely to hold him away. Let us step round together to the hotel,

and see if the porter can throw any fresh light upon the matter.”

Sherlock Holmes was a past-master in the art of putting a

humble witness at his ease, and very soon, in the privacy of Godfrey Staunton’s

abandoned room, he had extracted all that the porter had to tell. The visitor of the night

before was not a gentleman, neither was he a workingman. He was simply what the porter [625] described as a

“medium-looking chap,” a man of fifty, beard grizzled, pale face, quietly

dressed. He seemed himself to be agitated. The porter had observed his hand trembling when

he had held out the note. Godfrey Staunton had crammed the note into his pocket. Staunton

had not shaken hands with the man in the hall. They had exchanged a few sentences, of

which the porter had only distinguished the one word “time.” Then they had

hurried off in the manner described. It was just half-past ten by the hall clock. Sherlock Holmes was a past-master in the art of putting a

humble witness at his ease, and very soon, in the privacy of Godfrey Staunton’s

abandoned room, he had extracted all that the porter had to tell. The visitor of the night

before was not a gentleman, neither was he a workingman. He was simply what the porter [625] described as a

“medium-looking chap,” a man of fifty, beard grizzled, pale face, quietly

dressed. He seemed himself to be agitated. The porter had observed his hand trembling when

he had held out the note. Godfrey Staunton had crammed the note into his pocket. Staunton

had not shaken hands with the man in the hall. They had exchanged a few sentences, of

which the porter had only distinguished the one word “time.” Then they had

hurried off in the manner described. It was just half-past ten by the hall clock.

“Let me see,” said Holmes, seating himself on

Staunton’s bed. “You are the day porter, are you not?” “Let me see,” said Holmes, seating himself on

Staunton’s bed. “You are the day porter, are you not?”

“Yes, sir, I go off duty at eleven.” “Yes, sir, I go off duty at eleven.”

“The night porter saw nothing, I suppose?” “The night porter saw nothing, I suppose?”

“No, sir, one theatre party came in late. No one

else.” “No, sir, one theatre party came in late. No one

else.”

“Were you on duty all day yesterday?” “Were you on duty all day yesterday?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“Did you take any messages to Mr. Staunton?” “Did you take any messages to Mr. Staunton?”

“Yes, sir, one telegram.” “Yes, sir, one telegram.”

“Ah! that’s interesting. What o’clock was

this?” “Ah! that’s interesting. What o’clock was

this?”

“About six.” “About six.”

“Where was Mr. Staunton when he received it?” “Where was Mr. Staunton when he received it?”

“Here in his room.” “Here in his room.”

“Were you present when he opened it?” “Were you present when he opened it?”

“Yes, sir, I waited to see if there was an answer.” “Yes, sir, I waited to see if there was an answer.”

“Well, was there?” “Well, was there?”

“Yes, sir, he wrote an answer.” “Yes, sir, he wrote an answer.”

“Did you take it?” “Did you take it?”

“No, he took it himself.” “No, he took it himself.”

“But he wrote it in your presence?” “But he wrote it in your presence?”

“Yes, sir. I was standing by the door, and he with his

back turned to that table. When he had written it, he said: ‘All right, porter, I

will take this myself.’” “Yes, sir. I was standing by the door, and he with his

back turned to that table. When he had written it, he said: ‘All right, porter, I

will take this myself.’”

“What did he write it with?” “What did he write it with?”

“A pen, sir.” “A pen, sir.”

“Was the telegraphic form one of these on the

table?” “Was the telegraphic form one of these on the

table?”

“Yes, sir, it was the top one.” “Yes, sir, it was the top one.”

Holmes rose. Taking the forms, he carried them over to the

window and carefully examined that which was uppermost. Holmes rose. Taking the forms, he carried them over to the

window and carefully examined that which was uppermost.

“It is a pity he did not write in pencil,” said he,

throwing them down again with a shrug of disappointment. “As you have no doubt

frequently observed, Watson, the impression usually goes through–a fact which has

dissolved many a happy marriage. However, I can find no trace here. I rejoice, however, to

perceive that he wrote with a broad-pointed quill pen, and I can hardly doubt that we will

find some impression upon this blotting-pad. Ah, yes, surely this is the very thing!” “It is a pity he did not write in pencil,” said he,

throwing them down again with a shrug of disappointment. “As you have no doubt

frequently observed, Watson, the impression usually goes through–a fact which has

dissolved many a happy marriage. However, I can find no trace here. I rejoice, however, to

perceive that he wrote with a broad-pointed quill pen, and I can hardly doubt that we will

find some impression upon this blotting-pad. Ah, yes, surely this is the very thing!”

He tore off a strip of the blotting-paper and turned towards

us the following hieroglyphic: He tore off a strip of the blotting-paper and turned towards

us the following hieroglyphic:

[626] Cyril

Overton was much excited. “Hold it to the glass!” he cried. [626] Cyril

Overton was much excited. “Hold it to the glass!” he cried.

“That is unnecessary,” said Holmes. “The paper

is thin, and the reverse will give the message. Here it is.” He turned it over, and

we read: “That is unnecessary,” said Holmes. “The paper

is thin, and the reverse will give the message. Here it is.” He turned it over, and

we read:

“So that is the tail end of the telegram which Godfrey

Staunton dispatched within a few hours of his disappearance. There are at least six words

of the message which have escaped us; but what remains–‘Stand by us for

God’s sake!’ –proves that this young man saw a formidable danger which

approached him, and from which someone else could protect him. ‘Us,’

mark you! Another person was involved. Who should it be but the pale-faced, bearded man,

who seemed himself in so nervous a state? What, then, is the connection between Godfrey

Staunton and the bearded man? And what is the third source from which each of them sought

for help against pressing danger? Our inquiry has already narrowed down to that.” “So that is the tail end of the telegram which Godfrey

Staunton dispatched within a few hours of his disappearance. There are at least six words

of the message which have escaped us; but what remains–‘Stand by us for

God’s sake!’ –proves that this young man saw a formidable danger which

approached him, and from which someone else could protect him. ‘Us,’

mark you! Another person was involved. Who should it be but the pale-faced, bearded man,

who seemed himself in so nervous a state? What, then, is the connection between Godfrey

Staunton and the bearded man? And what is the third source from which each of them sought

for help against pressing danger? Our inquiry has already narrowed down to that.”

“We have only to find to whom that telegram is

addressed,” I suggested. “We have only to find to whom that telegram is

addressed,” I suggested.

“Exactly, my dear Watson. Your reflection, though

profound, had already crossed my mind. But I daresay it may have come to your notice that,

if you walk into a postoffice and demand to see the counterfoil of another man’s

message, there may be some disinclination on the part of the officials to oblige you.

There is so much red tape in these matters. However, I have no doubt that with a little

delicacy and finesse the end may be attained. Meanwhile, I should like in your presence,

Mr. Overton, to go through these papers which have been left upon the table.” “Exactly, my dear Watson. Your reflection, though

profound, had already crossed my mind. But I daresay it may have come to your notice that,

if you walk into a postoffice and demand to see the counterfoil of another man’s

message, there may be some disinclination on the part of the officials to oblige you.

There is so much red tape in these matters. However, I have no doubt that with a little

delicacy and finesse the end may be attained. Meanwhile, I should like in your presence,

Mr. Overton, to go through these papers which have been left upon the table.”

There were a number of letters, bills, and notebooks, which

Holmes turned over and examined with quick, nervous fingers and darting, penetrating eyes.

“Nothing here,” he said, at last. “By the way, I suppose your friend was a

healthy young fellow–nothing amiss with him?” There were a number of letters, bills, and notebooks, which

Holmes turned over and examined with quick, nervous fingers and darting, penetrating eyes.

“Nothing here,” he said, at last. “By the way, I suppose your friend was a

healthy young fellow–nothing amiss with him?”

“Sound as a bell.” “Sound as a bell.”

“Have you ever known him ill?” “Have you ever known him ill?”

“Not a day. He has been laid up with a hack, and once he

slipped his knee-cap, but that was nothing.” “Not a day. He has been laid up with a hack, and once he

slipped his knee-cap, but that was nothing.”

“Perhaps he was not so strong as you suppose. I should

think he may have had some secret trouble. With your assent, I will put one or two of

these papers in my pocket, in case they should bear upon our future inquiry.” “Perhaps he was not so strong as you suppose. I should

think he may have had some secret trouble. With your assent, I will put one or two of

these papers in my pocket, in case they should bear upon our future inquiry.”

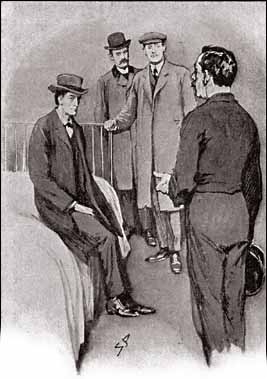

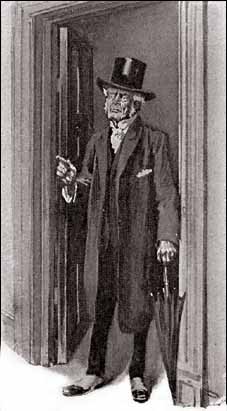

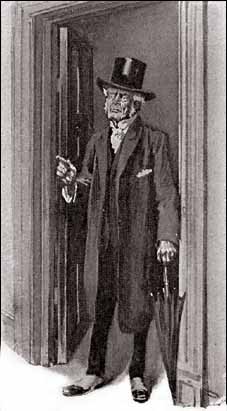

“One moment–one moment!” cried a querulous

voice, and we looked up to find a queer little old man, jerking and twitching in the

doorway. He was dressed in rusty black, with a very broad-brimmed top-hat and a loose

white necktie–the whole effect being that of a very rustic parson or of an

undertaker’s mute. Yet, in spite of his shabby and even absurd appearance, his voice

had a sharp crackle, and his manner a quick intensity which commanded attention. “One moment–one moment!” cried a querulous

voice, and we looked up to find a queer little old man, jerking and twitching in the

doorway. He was dressed in rusty black, with a very broad-brimmed top-hat and a loose

white necktie–the whole effect being that of a very rustic parson or of an

undertaker’s mute. Yet, in spite of his shabby and even absurd appearance, his voice

had a sharp crackle, and his manner a quick intensity which commanded attention.

“Who are you, sir, and by what right do you touch this

gentleman’s papers?” he asked. “Who are you, sir, and by what right do you touch this

gentleman’s papers?” he asked.

“I am a private detective, and I am endeavouring to

explain his disappearance.” “I am a private detective, and I am endeavouring to

explain his disappearance.”

“Oh, you are, are you? And who instructed you, eh?” “Oh, you are, are you? And who instructed you, eh?”

[627] “This

gentleman, Mr. Staunton’s friend, was referred to me by Scotland Yard.” [627] “This

gentleman, Mr. Staunton’s friend, was referred to me by Scotland Yard.”

“Who are you, sir?” “Who are you, sir?”

“I am Cyril Overton.” “I am Cyril Overton.”

“Then it is you who sent me a telegram. My name is Lord

Mount-James. I came round as quickly as the Bayswater bus would bring me. So you have

instructed a detective?” “Then it is you who sent me a telegram. My name is Lord

Mount-James. I came round as quickly as the Bayswater bus would bring me. So you have

instructed a detective?”

“Yes, sir.” “Yes, sir.”

“And are you prepared to meet the cost?” “And are you prepared to meet the cost?”

“I have no doubt, sir, that my friend Godfrey, when we

find him, will be prepared to do that.” “I have no doubt, sir, that my friend Godfrey, when we

find him, will be prepared to do that.”

“But if he is never found, eh? Answer me that!” “But if he is never found, eh? Answer me that!”

“In that case, no doubt his family– –” “In that case, no doubt his family– –”

“Nothing of the sort, sir!” screamed the little man.

“Don’t look to me for a penny–not a penny! You understand that, Mr.

Detective! I am all the family that this young man has got, and I tell you that I am not

responsible. If he has any expectations it is due to the fact that I have never wasted

money, and I do not propose to begin to do so now. As to those papers with which you are

making so free, I may tell you that in case there should be anything of any value among

them, you will be held strictly to account for what you do with them.” “Nothing of the sort, sir!” screamed the little man.

“Don’t look to me for a penny–not a penny! You understand that, Mr.

Detective! I am all the family that this young man has got, and I tell you that I am not

responsible. If he has any expectations it is due to the fact that I have never wasted

money, and I do not propose to begin to do so now. As to those papers with which you are

making so free, I may tell you that in case there should be anything of any value among

them, you will be held strictly to account for what you do with them.”

“Very good, sir,” said Sherlock Holmes. “May I

ask, in the meanwhile, whether you have yourself any theory to account for this young

man’s disappearance?” “Very good, sir,” said Sherlock Holmes. “May I

ask, in the meanwhile, whether you have yourself any theory to account for this young

man’s disappearance?”

“No, sir, I have not. He is big enough and old enough to

look after himself, and if he is so foolish as to lose himself, I entirely refuse to

accept the responsibility of hunting for him.” “No, sir, I have not. He is big enough and old enough to

look after himself, and if he is so foolish as to lose himself, I entirely refuse to

accept the responsibility of hunting for him.”

“I quite understand your position,” said Holmes,

with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. “Perhaps you don’t quite understand

mine. Godfrey Staunton appears to have been a poor man. If he has been kidnapped, it could

not have been for anything which he himself possesses. The fame of your wealth has gone

abroad, Lord Mount-James, and it is entirely possible that a gang of thieves have secured

your nephew in order to gain from him some information as to your house, your habits, and

your treasure.” “I quite understand your position,” said Holmes,

with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. “Perhaps you don’t quite understand

mine. Godfrey Staunton appears to have been a poor man. If he has been kidnapped, it could

not have been for anything which he himself possesses. The fame of your wealth has gone

abroad, Lord Mount-James, and it is entirely possible that a gang of thieves have secured

your nephew in order to gain from him some information as to your house, your habits, and

your treasure.”

The face of our unpleasant little visitor turned as white as

his neckcloth. The face of our unpleasant little visitor turned as white as

his neckcloth.

“Heavens, sir, what an idea! I never thought of such

villainy! What inhuman rogues there are in the world! But Godfrey is a fine lad–a

staunch lad. Nothing would induce him to give his old uncle away. I’ll have the plate

moved over to the bank this evening. In the meantime spare no pains, Mr. Detective! I beg

you to leave no stone unturned to bring him safely back. As to money, well, so far as a

fiver or even a tenner goes you can always look to me.” “Heavens, sir, what an idea! I never thought of such

villainy! What inhuman rogues there are in the world! But Godfrey is a fine lad–a

staunch lad. Nothing would induce him to give his old uncle away. I’ll have the plate

moved over to the bank this evening. In the meantime spare no pains, Mr. Detective! I beg

you to leave no stone unturned to bring him safely back. As to money, well, so far as a

fiver or even a tenner goes you can always look to me.”

Even in his chastened frame of mind, the noble miser could

give us no information which could help us, for he knew little of the private life of his

nephew. Our only clue lay in the truncated telegram, and with a copy of this in his hand

Holmes set forth to find a second link for his chain. We had shaken off Lord Mount-James,

and Overton had gone to consult with the other members of his team over the misfortune

which had befallen them. Even in his chastened frame of mind, the noble miser could

give us no information which could help us, for he knew little of the private life of his

nephew. Our only clue lay in the truncated telegram, and with a copy of this in his hand

Holmes set forth to find a second link for his chain. We had shaken off Lord Mount-James,

and Overton had gone to consult with the other members of his team over the misfortune

which had befallen them.

There was a telegraph-office at a short distance from the

hotel. We halted outside it. There was a telegraph-office at a short distance from the

hotel. We halted outside it.

“It’s worth trying, Watson,” said Holmes.

“Of course, with a warrant we could demand to see the counterfoils, but we have not

reached that stage yet. I don’t suppose they remember faces in so busy a place. Let

us venture it.” “It’s worth trying, Watson,” said Holmes.

“Of course, with a warrant we could demand to see the counterfoils, but we have not

reached that stage yet. I don’t suppose they remember faces in so busy a place. Let

us venture it.”

[628] “I

am sorry to trouble you,” said he, in his blandest manner, to the young woman behind

the grating; “there is some small mistake about a telegram I sent yesterday. I have

had no answer, and I very much fear that I must have omitted to put my name at the end.

Could you tell me if this was so?” [628] “I

am sorry to trouble you,” said he, in his blandest manner, to the young woman behind

the grating; “there is some small mistake about a telegram I sent yesterday. I have

had no answer, and I very much fear that I must have omitted to put my name at the end.

Could you tell me if this was so?”

The young woman turned over a sheaf of counterfoils. The young woman turned over a sheaf of counterfoils.

“What o’clock was it?” she asked. “What o’clock was it?” she asked.

“A little after six.” “A little after six.”

“Whom was it to?” “Whom was it to?”

Holmes put his finger to his lips and glanced at me. “The

last words in it were ‘for God’s sake,’” he whispered, confidentially;

“I am very anxious at getting no answer.” Holmes put his finger to his lips and glanced at me. “The

last words in it were ‘for God’s sake,’” he whispered, confidentially;

“I am very anxious at getting no answer.”

The young woman separated one of the forms. The young woman separated one of the forms.

“This is it. There is no name,” said she, smoothing

it out upon the counter. “This is it. There is no name,” said she, smoothing

it out upon the counter.

“Then that, of course, accounts for my getting no

answer,” said Holmes. “Dear me, how very stupid of me, to be sure! Good-morning,

miss, and many thanks for having relieved my mind.” He chuckled and rubbed his hands

when we found ourselves in the street once more. “Then that, of course, accounts for my getting no

answer,” said Holmes. “Dear me, how very stupid of me, to be sure! Good-morning,

miss, and many thanks for having relieved my mind.” He chuckled and rubbed his hands

when we found ourselves in the street once more.

“Well?” I asked. “Well?” I asked.

“We progress, my dear Watson, we progress. I had seven

different schemes for getting a glimpse of that telegram, but I could hardly hope to

succeed the very first time.” “We progress, my dear Watson, we progress. I had seven

different schemes for getting a glimpse of that telegram, but I could hardly hope to

succeed the very first time.”

“And what have you gained?” “And what have you gained?”

“A starting-point for our investigation.” He hailed

a cab. “King’s Cross Station,” said he. “A starting-point for our investigation.” He hailed

a cab. “King’s Cross Station,” said he.

“We have a journey, then?” “We have a journey, then?”

“Yes, I think we must run down to Cambridge together. All

the indications seem to me to point in that direction.” “Yes, I think we must run down to Cambridge together. All

the indications seem to me to point in that direction.”

“Tell me,” I asked, as we rattled up Gray’s Inn

Road, “have you any suspicion yet as to the cause of the disappearance? I don’t

think that among all our cases I have known one where the motives are more obscure. Surely

you don’t really imagine that he may be kidnapped in order to give information

against his wealthy uncle?” “Tell me,” I asked, as we rattled up Gray’s Inn

Road, “have you any suspicion yet as to the cause of the disappearance? I don’t

think that among all our cases I have known one where the motives are more obscure. Surely

you don’t really imagine that he may be kidnapped in order to give information

against his wealthy uncle?”

“I confess, my dear Watson, that that does not appeal to

me as a very probable explanation. It struck me, however, as being the one which was most

likely to interest that exceedingly unpleasant old person.” “I confess, my dear Watson, that that does not appeal to

me as a very probable explanation. It struck me, however, as being the one which was most

likely to interest that exceedingly unpleasant old person.”

“It certainly did that; but what are your

alternatives?” “It certainly did that; but what are your

alternatives?”

“I could mention several. You must admit that it is

curious and suggestive that this incident should occur on the eve of this important match,

and should involve the only man whose presence seems essential to the success of the side.

It may, of course, be a coincidence, but it is interesting. Amateur sport is free from

betting, but a good deal of outside betting goes on among the public, and it is possible

that it might be worth someone’s while to get at a player as the ruffians of the turf

get at a race-horse. There is one explanation. A second very obvious one is that this

young man really is the heir of a great property, however modest his means may at present

be, and it is not impossible that a plot to hold him for ransom might be concocted.” “I could mention several. You must admit that it is

curious and suggestive that this incident should occur on the eve of this important match,

and should involve the only man whose presence seems essential to the success of the side.

It may, of course, be a coincidence, but it is interesting. Amateur sport is free from

betting, but a good deal of outside betting goes on among the public, and it is possible

that it might be worth someone’s while to get at a player as the ruffians of the turf

get at a race-horse. There is one explanation. A second very obvious one is that this

young man really is the heir of a great property, however modest his means may at present

be, and it is not impossible that a plot to hold him for ransom might be concocted.”

“These theories take no account of the telegram.” “These theories take no account of the telegram.”

“Quite true, Watson. The telegram still remains the only

solid thing with which we have to deal, and we must not permit our attention to wander

away from it. [629] It is to

gain light upon the purpose of this telegram that we are now upon our way to Cambridge.

The path of our investigation is at present obscure, but I shall be very much surprised if

before evening we have not cleared it up, or made a considerable advance along it.” “Quite true, Watson. The telegram still remains the only

solid thing with which we have to deal, and we must not permit our attention to wander

away from it. [629] It is to

gain light upon the purpose of this telegram that we are now upon our way to Cambridge.

The path of our investigation is at present obscure, but I shall be very much surprised if

before evening we have not cleared it up, or made a considerable advance along it.”

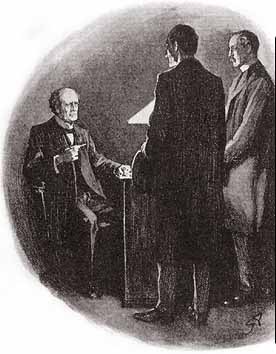

It was already dark when we reached the old university city.

Holmes took a cab at the station and ordered the man to drive to the house of Dr. Leslie

Armstrong. A few minutes later, we had stopped at a large mansion on the busiest

thoroughfare. We were shown in, and after a long wait were at last admitted into the

consulting-room, where we found the doctor seated behind his table. It was already dark when we reached the old university city.

Holmes took a cab at the station and ordered the man to drive to the house of Dr. Leslie

Armstrong. A few minutes later, we had stopped at a large mansion on the busiest

thoroughfare. We were shown in, and after a long wait were at last admitted into the

consulting-room, where we found the doctor seated behind his table.

It argues the degree in which I had lost touch with my

profession that the name of Leslie Armstrong was unknown to me. Now I am aware that he is

not only one of the heads of the medical school of the university, but a thinker of

European reputation in more than one branch of science. Yet even without knowing his

brilliant record one could not fail to be impressed by a mere glance at the man, the

square, massive face, the brooding eyes under the thatched brows, and the granite moulding

of the inflexible jaw. A man of deep character, a man with an alert mind, grim, ascetic,

self-contained, formidable–so I read Dr. Leslie Armstrong. He held my friend’s

card in his hand, and he looked up with no very pleased expression upon his dour features. It argues the degree in which I had lost touch with my

profession that the name of Leslie Armstrong was unknown to me. Now I am aware that he is

not only one of the heads of the medical school of the university, but a thinker of

European reputation in more than one branch of science. Yet even without knowing his

brilliant record one could not fail to be impressed by a mere glance at the man, the

square, massive face, the brooding eyes under the thatched brows, and the granite moulding

of the inflexible jaw. A man of deep character, a man with an alert mind, grim, ascetic,

self-contained, formidable–so I read Dr. Leslie Armstrong. He held my friend’s

card in his hand, and he looked up with no very pleased expression upon his dour features.

“I have heard your name, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and I am

aware of your profession–one of which I by no means approve.” “I have heard your name, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and I am

aware of your profession–one of which I by no means approve.”

“In that, Doctor, you will find yourself in agreement

with every criminal in the country,” said my friend, quietly. “In that, Doctor, you will find yourself in agreement

with every criminal in the country,” said my friend, quietly.

“So far as your efforts are directed towards the

suppression of crime, sir, they must have the support of every reasonable member of the

community, though I cannot doubt that the official machinery is amply sufficient for the

purpose. Where your calling is more open to criticism is when you pry into the secrets of

private individuals, when you rake up family matters which are better hidden, and when you

incidentally waste the time of men who are more busy than yourself. At the present moment,

for example, I should be writing a treatise instead of conversing with you.” “So far as your efforts are directed towards the

suppression of crime, sir, they must have the support of every reasonable member of the

community, though I cannot doubt that the official machinery is amply sufficient for the

purpose. Where your calling is more open to criticism is when you pry into the secrets of

private individuals, when you rake up family matters which are better hidden, and when you

incidentally waste the time of men who are more busy than yourself. At the present moment,

for example, I should be writing a treatise instead of conversing with you.”

“No doubt, Doctor; and yet the conversation may prove

more important than the treatise. Incidentally, I may tell you that we are doing the

reverse of what you very justly blame, and that we are endeavouring to prevent anything

like public exposure of private matters which must necessarily follow when once the case

is fairly in the hands of the official police. You may look upon me simply as an irregular

pioneer, who goes in front of the regular forces of the country. I have come to ask you

about Mr. Godfrey Staunton.” “No doubt, Doctor; and yet the conversation may prove

more important than the treatise. Incidentally, I may tell you that we are doing the

reverse of what you very justly blame, and that we are endeavouring to prevent anything

like public exposure of private matters which must necessarily follow when once the case

is fairly in the hands of the official police. You may look upon me simply as an irregular

pioneer, who goes in front of the regular forces of the country. I have come to ask you

about Mr. Godfrey Staunton.”

“What about him?” “What about him?”

“You know him, do you not?” “You know him, do you not?”

“He is an intimate friend of mine.” “He is an intimate friend of mine.”

“You are aware that he has disappeared?” “You are aware that he has disappeared?”

“Ah, indeed!” There was no change of expression in

the rugged features of the doctor. “Ah, indeed!” There was no change of expression in

the rugged features of the doctor.

“He left his hotel last night–he has not been heard

of.” “He left his hotel last night–he has not been heard

of.”

“No doubt he will return.” “No doubt he will return.”

“To-morrow is the ’Varsity football match.” “To-morrow is the ’Varsity football match.”

“I have no sympathy with these childish games. The young

man’s fate interests [630] me

deeply, since I know him and like him. The football match does not come within my horizon

at all.” “I have no sympathy with these childish games. The young

man’s fate interests [630] me

deeply, since I know him and like him. The football match does not come within my horizon

at all.”

“I claim your sympathy, then, in my investigation of Mr.

Staunton’s fate. Do you know where he is?” “I claim your sympathy, then, in my investigation of Mr.

Staunton’s fate. Do you know where he is?”

“Certainly not.” “Certainly not.”

“You have not seen him since yesterday?” “You have not seen him since yesterday?”

“No, I have not.” “No, I have not.”

“Was Mr. Staunton a healthy man?” “Was Mr. Staunton a healthy man?”

“Absolutely.” “Absolutely.”

“Did you ever know him ill?” “Did you ever know him ill?”

“Never.” “Never.”

Holmes popped a sheet of paper before the doctor’s eyes.

“Then perhaps you will explain this receipted bill for thirteen guineas, paid by Mr.

Godfrey Staunton last month to Dr. Leslie Armstrong, of Cambridge. I picked it out from

among the papers upon his desk.” Holmes popped a sheet of paper before the doctor’s eyes.

“Then perhaps you will explain this receipted bill for thirteen guineas, paid by Mr.

Godfrey Staunton last month to Dr. Leslie Armstrong, of Cambridge. I picked it out from

among the papers upon his desk.”

The doctor flushed with anger. The doctor flushed with anger.

“I do not feel that there is any reason why I should

render an explanation to you, Mr. Holmes.” “I do not feel that there is any reason why I should

render an explanation to you, Mr. Holmes.”

Holmes replaced the bill in his notebook. “If you prefer

a public explanation, it must come sooner or later,” said he. “I have already

told you that I can hush up that which others will be bound to publish, and you would

really be wiser to take me into your complete confidence.” Holmes replaced the bill in his notebook. “If you prefer

a public explanation, it must come sooner or later,” said he. “I have already

told you that I can hush up that which others will be bound to publish, and you would

really be wiser to take me into your complete confidence.”

“I know nothing about it.” “I know nothing about it.”

“Did you hear from Mr. Staunton in London?” “Did you hear from Mr. Staunton in London?”

“Certainly not.” “Certainly not.”

“Dear me, dear me–the postoffice again!” Holmes

sighed, wearily. “A most urgent telegram was dispatched to you from London by Godfrey

Staunton at six-fifteen yesterday evening–a telegram which is undoubtedly associated

with his disappearance–and yet you have not had it. It is most culpable. I shall

certainly go down to the office here and register a complaint.” “Dear me, dear me–the postoffice again!” Holmes

sighed, wearily. “A most urgent telegram was dispatched to you from London by Godfrey

Staunton at six-fifteen yesterday evening–a telegram which is undoubtedly associated

with his disappearance–and yet you have not had it. It is most culpable. I shall

certainly go down to the office here and register a complaint.”

Dr. Leslie Armstrong sprang up from behind his desk, and his

dark face was crimson with fury. Dr. Leslie Armstrong sprang up from behind his desk, and his

dark face was crimson with fury.

“I’ll trouble you to walk out of my house,

sir,” said he. “You can tell your employer, Lord Mount-James, that I do not wish

to have anything to do either with him or with his agents. No, sir–not another

word!” He rang the bell furiously. “John, show these gentlemen out!” A

pompous butler ushered us severely to the door, and we found ourselves in the street.

Holmes burst out laughing. “I’ll trouble you to walk out of my house,

sir,” said he. “You can tell your employer, Lord Mount-James, that I do not wish

to have anything to do either with him or with his agents. No, sir–not another

word!” He rang the bell furiously. “John, show these gentlemen out!” A

pompous butler ushered us severely to the door, and we found ourselves in the street.

Holmes burst out laughing.

“Dr. Leslie Armstrong is certainly a man of energy and

character,” said he. “I have not seen a man who, if he turns his talents that

way, was more calculated to fill the gap left by the illustrious Moriarty. And now, my

poor Watson, here we are, stranded and friendless in this inhospitable town, which we

cannot leave without abandoning our case. This little inn just opposite Armstrong’s

house is singularly adapted to our needs. If you would engage a front room and purchase

the necessaries for the night, I may have time to make a few inquiries.” “Dr. Leslie Armstrong is certainly a man of energy and

character,” said he. “I have not seen a man who, if he turns his talents that

way, was more calculated to fill the gap left by the illustrious Moriarty. And now, my

poor Watson, here we are, stranded and friendless in this inhospitable town, which we

cannot leave without abandoning our case. This little inn just opposite Armstrong’s

house is singularly adapted to our needs. If you would engage a front room and purchase

the necessaries for the night, I may have time to make a few inquiries.”

These few inquiries proved, however, to be a more lengthy

proceeding than Holmes had imagined, for he did not return to the inn until nearly nine

o’clock. He was pale and dejected, stained with dust, and exhausted with hunger and

fatigue. A cold supper was ready upon the table, and when his needs were satisfied and his

pipe alight he was ready to take that half comic and wholly philosophic [631] view which was natural to

him when his affairs were going awry. The sound of carriage wheels caused him to rise and

glance out of the window. A brougham and pair of grays, under the glare of a gas-lamp,

stood before the doctor’s door. These few inquiries proved, however, to be a more lengthy

proceeding than Holmes had imagined, for he did not return to the inn until nearly nine

o’clock. He was pale and dejected, stained with dust, and exhausted with hunger and

fatigue. A cold supper was ready upon the table, and when his needs were satisfied and his

pipe alight he was ready to take that half comic and wholly philosophic [631] view which was natural to

him when his affairs were going awry. The sound of carriage wheels caused him to rise and

glance out of the window. A brougham and pair of grays, under the glare of a gas-lamp,

stood before the doctor’s door.

“It’s been out three hours,” said Holmes;

“started at half-past six, and here it is back again. That gives a radius of ten or

twelve miles, and he does it once, or sometimes twice, a day.” “It’s been out three hours,” said Holmes;

“started at half-past six, and here it is back again. That gives a radius of ten or

twelve miles, and he does it once, or sometimes twice, a day.”

“No unusual thing for a doctor in practice.” “No unusual thing for a doctor in practice.”

“But Armstrong is not really a doctor in practice. He is

a lecturer and a consultant, but he does not care for general practice, which distracts

him from his literary work. Why, then, does he make these long journeys, which must be

exceedingly irksome to him, and who is it that he visits?” “But Armstrong is not really a doctor in practice. He is

a lecturer and a consultant, but he does not care for general practice, which distracts

him from his literary work. Why, then, does he make these long journeys, which must be

exceedingly irksome to him, and who is it that he visits?”

“His coachman– –” “His coachman– –”

“My dear Watson, can you doubt that it was to him that I

first applied? I do not know whether it came from his own innate depravity or from the

promptings of his master, but he was rude enough to set a dog at me. Neither dog nor man

liked the look of my stick, however, and the matter fell through. Relations were strained

after that, and further inquiries out of the question. All that I have learned I got from

a friendly native in the yard of our own inn. It was he who told me of the doctor’s

habits and of his daily journey. At that instant, to give point to his words, the carriage

came round to the door.” “My dear Watson, can you doubt that it was to him that I

first applied? I do not know whether it came from his own innate depravity or from the

promptings of his master, but he was rude enough to set a dog at me. Neither dog nor man

liked the look of my stick, however, and the matter fell through. Relations were strained

after that, and further inquiries out of the question. All that I have learned I got from

a friendly native in the yard of our own inn. It was he who told me of the doctor’s

habits and of his daily journey. At that instant, to give point to his words, the carriage

came round to the door.”

“Could you not follow it?” “Could you not follow it?”

“Excellent, Watson! You are scintillating this evening.

The idea did cross my mind. There is, as you may have observed, a bicycle shop next to our

inn. Into this I rushed, engaged a bicycle, and was able to get started before the

carriage was quite out of sight. I rapidly overtook it, and then, keeping at a discreet

distance of a hundred yards or so, I followed its lights until we were clear of the town.

We had got well out on the country road, when a somewhat mortifying incident occurred. The

carriage stopped, the doctor alighted, walked swiftly back to where I had also halted, and

told me in an excellent sardonic fashion that he feared the road was narrow, and that he

hoped his carriage did not impede the passage of my bicycle. Nothing could have been more

admirable than his way of putting it. I at once rode past the carriage, and, keeping to

the main road, I went on for a few miles, and then halted in a convenient place to see if

the carriage passed. There was no sign of it, however, and so it became evident that it

had turned down one of several side roads which I had observed. I rode back, but again saw

nothing of the carriage, and now, as you perceive, it has returned after me. Of course, I

had at the outset no particular reason to connect these journeys with the disappearance of

Godfrey Staunton, and was only inclined to investigate them on the general grounds that

everything which concerns Dr. Armstrong is at present of interest to us, but, now that I

find he keeps so keen a look-out upon anyone who may follow him on these excursions, the

affair appears more important, and I shall not be satisfied until I have made the matter

clear.” “Excellent, Watson! You are scintillating this evening.

The idea did cross my mind. There is, as you may have observed, a bicycle shop next to our

inn. Into this I rushed, engaged a bicycle, and was able to get started before the

carriage was quite out of sight. I rapidly overtook it, and then, keeping at a discreet

distance of a hundred yards or so, I followed its lights until we were clear of the town.

We had got well out on the country road, when a somewhat mortifying incident occurred. The

carriage stopped, the doctor alighted, walked swiftly back to where I had also halted, and

told me in an excellent sardonic fashion that he feared the road was narrow, and that he

hoped his carriage did not impede the passage of my bicycle. Nothing could have been more

admirable than his way of putting it. I at once rode past the carriage, and, keeping to

the main road, I went on for a few miles, and then halted in a convenient place to see if

the carriage passed. There was no sign of it, however, and so it became evident that it

had turned down one of several side roads which I had observed. I rode back, but again saw

nothing of the carriage, and now, as you perceive, it has returned after me. Of course, I

had at the outset no particular reason to connect these journeys with the disappearance of

Godfrey Staunton, and was only inclined to investigate them on the general grounds that

everything which concerns Dr. Armstrong is at present of interest to us, but, now that I

find he keeps so keen a look-out upon anyone who may follow him on these excursions, the

affair appears more important, and I shall not be satisfied until I have made the matter

clear.”

“We can follow him to-morrow.” “We can follow him to-morrow.”

“Can we? It is not so easy as you seem to think. You are

not familiar with Cambridgeshire scenery, are you? It does not lend itself to concealment.

All this country that I passed over to-night is as flat and clean as the palm of your

hand, and the man we are following is no fool, as he very clearly showed to-night. I have

wired to Overton to let us know any fresh London developments at this address, and in the

meantime we can only concentrate our attention upon Dr. Armstrong, [632] whose name the obliging young lady at the office

allowed me to read upon the counterfoil of Staunton’s urgent message. He knows where

the young man is–to that I’ll swear, and if he knows, then it must be our own

fault if we cannot manage to know also. At present it must be admitted that the odd trick

is in his possession, and, as you are aware, Watson, it is not my habit to leave the game

in that condition.” “Can we? It is not so easy as you seem to think. You are

not familiar with Cambridgeshire scenery, are you? It does not lend itself to concealment.

All this country that I passed over to-night is as flat and clean as the palm of your

hand, and the man we are following is no fool, as he very clearly showed to-night. I have

wired to Overton to let us know any fresh London developments at this address, and in the

meantime we can only concentrate our attention upon Dr. Armstrong, [632] whose name the obliging young lady at the office

allowed me to read upon the counterfoil of Staunton’s urgent message. He knows where

the young man is–to that I’ll swear, and if he knows, then it must be our own

fault if we cannot manage to know also. At present it must be admitted that the odd trick

is in his possession, and, as you are aware, Watson, it is not my habit to leave the game

in that condition.”

And yet the next day brought us no nearer to the solution of

the mystery. A note was handed in after breakfast, which Holmes passed across to me with a

smile. And yet the next day brought us no nearer to the solution of

the mystery. A note was handed in after breakfast, which Holmes passed across to me with a

smile.

- SIR [it ran]:

I can assure you that you are wasting your time in dogging my

movements. I have, as you discovered last night, a window at the back of my brougham, and

if you desire a twenty-mile ride which will lead you to the spot from which you started,

you have only to follow me. Meanwhile, I can inform you that no spying upon me can in any

way help Mr. Godfrey Staunton, and I am convinced that the best service you can do to that

gentleman is to return at once to London and to report to your employer that you are

unable to trace him. Your time in Cambridge will certainly be wasted. I can assure you that you are wasting your time in dogging my

movements. I have, as you discovered last night, a window at the back of my brougham, and

if you desire a twenty-mile ride which will lead you to the spot from which you started,

you have only to follow me. Meanwhile, I can inform you that no spying upon me can in any

way help Mr. Godfrey Staunton, and I am convinced that the best service you can do to that

gentleman is to return at once to London and to report to your employer that you are

unable to trace him. Your time in Cambridge will certainly be wasted.

- Yours faithfully,

- LESLIE ARMSTRONG.

“An outspoken, honest antagonist is the doctor,”

said Holmes. “Well, well, he excites my curiosity, and I must really know before I

leave him.” “An outspoken, honest antagonist is the doctor,”

said Holmes. “Well, well, he excites my curiosity, and I must really know before I

leave him.”

“His carriage is at his door now,” said I.

“There he is stepping into it. I saw him glance up at our window as he did so.

Suppose I try my luck upon the bicycle?” “His carriage is at his door now,” said I.

“There he is stepping into it. I saw him glance up at our window as he did so.

Suppose I try my luck upon the bicycle?”

“No, no, my dear Watson! With all respect for your

natural acumen, I do not think that you are quite a match for the worthy doctor. I think

that possibly I can attain our end by some independent explorations of my own. I am afraid

that I must leave you to your own devices, as the appearance of two inquiring strangers

upon a sleepy countryside might excite more gossip than I care for. No doubt you will find

some sights to amuse you in this venerable city, and I hope to bring back a more

favourable report to you before evening.” “No, no, my dear Watson! With all respect for your

natural acumen, I do not think that you are quite a match for the worthy doctor. I think

that possibly I can attain our end by some independent explorations of my own. I am afraid

that I must leave you to your own devices, as the appearance of two inquiring strangers

upon a sleepy countryside might excite more gossip than I care for. No doubt you will find

some sights to amuse you in this venerable city, and I hope to bring back a more

favourable report to you before evening.”

Once more, however, my friend was destined to be disappointed.

He came back at night weary and unsuccessful. Once more, however, my friend was destined to be disappointed.

He came back at night weary and unsuccessful.

“I have had a blank day, Watson. Having got the

doctor’s general direction, I spent the day in visiting all the villages upon that

side of Cambridge, and comparing notes with publicans and other local news agencies. I

have covered some ground. Chesterton, Histon, Waterbeach, and Oakington have each been

explored, and have each proved disappointing. The daily appearance of a brougham and pair

could hardly have been overlooked in such Sleepy Hollows. The doctor has scored once more.

Is there a telegram for me?” “I have had a blank day, Watson. Having got the

doctor’s general direction, I spent the day in visiting all the villages upon that

side of Cambridge, and comparing notes with publicans and other local news agencies. I

have covered some ground. Chesterton, Histon, Waterbeach, and Oakington have each been

explored, and have each proved disappointing. The daily appearance of a brougham and pair

could hardly have been overlooked in such Sleepy Hollows. The doctor has scored once more.

Is there a telegram for me?”

“Yes, I opened it. Here it is: “Yes, I opened it. Here it is:

- “Ask for Pompey from Jeremy Dixon, Trinity College.

I don’t understand it.”

“Oh, it is clear enough. It is from our friend Overton,

and is in answer to a question from me. I’ll just send round a note to Mr. Jeremy

Dixon, and then I have no doubt that our luck will turn. By the way, is there any news of

the match?” “Oh, it is clear enough. It is from our friend Overton,

and is in answer to a question from me. I’ll just send round a note to Mr. Jeremy

Dixon, and then I have no doubt that our luck will turn. By the way, is there any news of

the match?”

“Yes, the local evening paper has an excellent account in

its last edition. Oxford won by a goal and two tries. The last sentences of the

description say: “Yes, the local evening paper has an excellent account in

its last edition. Oxford won by a goal and two tries. The last sentences of the

description say:

[633] “The

defeat of the Light Blues may be entirely attributed to the unfortunate absence of the

crack International, Godfrey Staunton, whose want was felt at every instant of the game.

The lack of combination in the three-quarter line and their weakness both in attack and

defence more than neutralized the efforts of a heavy and hard-working pack.” [633] “The

defeat of the Light Blues may be entirely attributed to the unfortunate absence of the

crack International, Godfrey Staunton, whose want was felt at every instant of the game.

The lack of combination in the three-quarter line and their weakness both in attack and

defence more than neutralized the efforts of a heavy and hard-working pack.”

“Then our friend Overton’s forebodings have been

justified,” said Holmes. “Personally I am in agreement with Dr. Armstrong, and

football does not come within my horizon. Early to bed to-night, Watson, for I foresee

that to-morrow may be an eventful day.” “Then our friend Overton’s forebodings have been

justified,” said Holmes. “Personally I am in agreement with Dr. Armstrong, and

football does not come within my horizon. Early to bed to-night, Watson, for I foresee

that to-morrow may be an eventful day.”

I was horrified by my first glimpse of Holmes next morning,

for he sat by the fire holding his tiny hypodermic syringe. I associated that instrument

with the single weakness of his nature, and I feared the worst when I saw it glittering in

his hand. He laughed at my expression of dismay and laid it upon the table. I was horrified by my first glimpse of Holmes next morning,

for he sat by the fire holding his tiny hypodermic syringe. I associated that instrument

with the single weakness of his nature, and I feared the worst when I saw it glittering in

his hand. He laughed at my expression of dismay and laid it upon the table.

“No, no, my dear fellow, there is no cause for alarm. It

is not upon this occasion the instrument of evil, but it will rather prove to be the key

which will unlock our mystery. On this syringe I base all my hopes. I have just returned

from a small scouting expedition, and everything is favourable. Eat a good breakfast,

Watson, for I propose to get upon Dr. Armstrong’s trail to-day, and once on it I will

not stop for rest or food until I run him to his burrow.” “No, no, my dear fellow, there is no cause for alarm. It

is not upon this occasion the instrument of evil, but it will rather prove to be the key

which will unlock our mystery. On this syringe I base all my hopes. I have just returned

from a small scouting expedition, and everything is favourable. Eat a good breakfast,

Watson, for I propose to get upon Dr. Armstrong’s trail to-day, and once on it I will

not stop for rest or food until I run him to his burrow.”

“In that case,” said I, “we had best carry our

breakfast with us, for he is making an early start. His carriage is at the door.” “In that case,” said I, “we had best carry our

breakfast with us, for he is making an early start. His carriage is at the door.”

“Never mind. Let him go. He will be clever if he can

drive where I cannot follow him. When you have finished, come downstairs with me, and I

will introduce you to a detective who is a very eminent specialist in the work that lies

before us.” “Never mind. Let him go. He will be clever if he can

drive where I cannot follow him. When you have finished, come downstairs with me, and I

will introduce you to a detective who is a very eminent specialist in the work that lies

before us.”

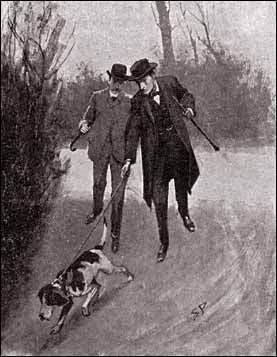

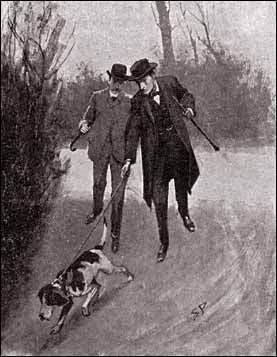

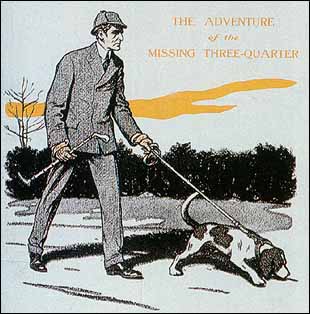

When we descended I followed Holmes into the stable yard,

where he opened the door of a loose-box and led out a squat, lop-eared, white-and-tan dog,

something between a beagle and a foxhound. When we descended I followed Holmes into the stable yard,

where he opened the door of a loose-box and led out a squat, lop-eared, white-and-tan dog,

something between a beagle and a foxhound.

“Let me introduce you to Pompey,” said he.

“Pompey is the pride of the local draghounds–no very great flier, as his build

will show, but a staunch hound on a scent. Well, Pompey, you may not be fast, but I expect

you will be too fast for a couple of middle-aged London gentlemen, so I will take the

liberty of fastening this leather leash to your collar. Now, boy, come along, and show

what you can do.” He led him across to the doctor’s door. The dog sniffed round

for an instant, and then with a shrill whine of excitement started off down the street,

tugging at his leash in his efforts to go faster. In half an hour, we were clear of the

town and hastening down a country road. “Let me introduce you to Pompey,” said he.

“Pompey is the pride of the local draghounds–no very great flier, as his build

will show, but a staunch hound on a scent. Well, Pompey, you may not be fast, but I expect

you will be too fast for a couple of middle-aged London gentlemen, so I will take the

liberty of fastening this leather leash to your collar. Now, boy, come along, and show

what you can do.” He led him across to the doctor’s door. The dog sniffed round

for an instant, and then with a shrill whine of excitement started off down the street,

tugging at his leash in his efforts to go faster. In half an hour, we were clear of the

town and hastening down a country road.

“What have you done, Holmes?” I asked. “What have you done, Holmes?” I asked.

“A threadbare and venerable device, but useful upon

occasion. I walked into the doctor’s yard this morning, and shot my syringe full of

aniseed over the hind wheel. A draghound will follow aniseed from here to John o’

Groat’s, and our friend, Armstrong, would have to drive through the Cam before he

would shake Pompey off his trail. Oh, the cunning rascal! This is how he gave me the slip

the other night.” “A threadbare and venerable device, but useful upon

occasion. I walked into the doctor’s yard this morning, and shot my syringe full of

aniseed over the hind wheel. A draghound will follow aniseed from here to John o’

Groat’s, and our friend, Armstrong, would have to drive through the Cam before he

would shake Pompey off his trail. Oh, the cunning rascal! This is how he gave me the slip

the other night.”

The dog had suddenly turned out of the main road into a

grass-grown lane. Half a mile farther this opened into another broad road, and the trail

turned hard to the right in the direction of the town, which we had just quitted. The road

took a sweep to the south of the town, and continued in the opposite direction to that in

which we started. The dog had suddenly turned out of the main road into a

grass-grown lane. Half a mile farther this opened into another broad road, and the trail

turned hard to the right in the direction of the town, which we had just quitted. The road

took a sweep to the south of the town, and continued in the opposite direction to that in

which we started.

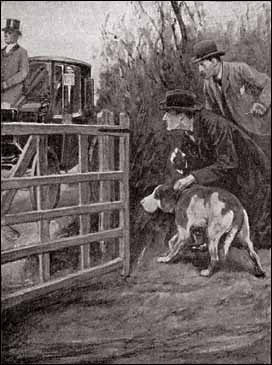

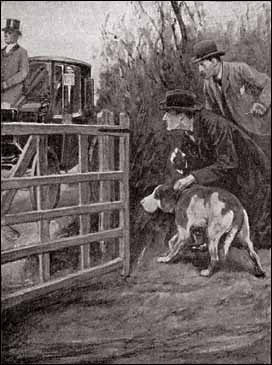

[634] “This

d�tour has been entirely for our benefit, then?” said Holmes. “No

wonder that my inquiries among those villagers led to nothing. The doctor has certainly

played the game for all it is worth, and one would like to know the reason for such

elaborate deception. This should be the village of Trumpington to the right of us. And, by

Jove! here is the brougham coming round the corner. Quick, Watson–quick, or we are

done!” [634] “This

d�tour has been entirely for our benefit, then?” said Holmes. “No

wonder that my inquiries among those villagers led to nothing. The doctor has certainly

played the game for all it is worth, and one would like to know the reason for such

elaborate deception. This should be the village of Trumpington to the right of us. And, by

Jove! here is the brougham coming round the corner. Quick, Watson–quick, or we are

done!”

He sprang through a gate into a field, dragging the reluctant

Pompey after him. We had hardly got under the shelter of the hedge when the carriage

rattled past. I caught a glimpse of Dr. Armstrong within, his shoulders bowed, his head

sunk on his hands, the very image of distress. I could tell by my companion’s graver

face that he also had seen. He sprang through a gate into a field, dragging the reluctant

Pompey after him. We had hardly got under the shelter of the hedge when the carriage

rattled past. I caught a glimpse of Dr. Armstrong within, his shoulders bowed, his head

sunk on his hands, the very image of distress. I could tell by my companion’s graver

face that he also had seen.

“I fear there is some dark ending to our quest,”

said he. “It cannot be long before we know it. Come, Pompey! Ah, it is the cottage in

the field!” “I fear there is some dark ending to our quest,”

said he. “It cannot be long before we know it. Come, Pompey! Ah, it is the cottage in

the field!”

There could be no doubt that we had reached the end of our

journey. Pompey ran about and whined eagerly outside the gate, where the marks of the

brougham’s wheels were still to be seen. A footpath led across to the lonely cottage.

Holmes tied the dog to the hedge, and we hastened onward. My friend knocked at the little

rustic door, and knocked again without response. And yet the cottage was not deserted, for

a low sound came to our ears–a kind of drone of misery and despair which was

indescribably melancholy. Holmes paused irresolute, and then he glanced back at the road

which he had just traversed. A brougham was coming down it, and there could be no

mistaking those gray horses. There could be no doubt that we had reached the end of our

journey. Pompey ran about and whined eagerly outside the gate, where the marks of the

brougham’s wheels were still to be seen. A footpath led across to the lonely cottage.

Holmes tied the dog to the hedge, and we hastened onward. My friend knocked at the little

rustic door, and knocked again without response. And yet the cottage was not deserted, for

a low sound came to our ears–a kind of drone of misery and despair which was

indescribably melancholy. Holmes paused irresolute, and then he glanced back at the road

which he had just traversed. A brougham was coming down it, and there could be no

mistaking those gray horses.

“By Jove, the doctor is coming back!” cried Holmes.

“That settles it. We are bound to see what it means before he comes.” “By Jove, the doctor is coming back!” cried Holmes.

“That settles it. We are bound to see what it means before he comes.”

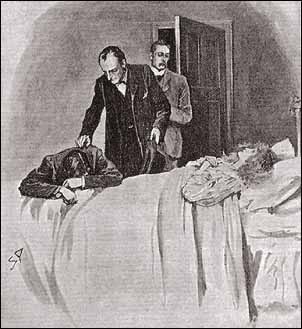

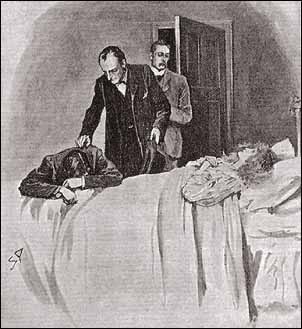

He opened the door, and we stepped into the hall. The droning

sound swelled louder upon our ears until it became one long, deep wail of distress. It

came from upstairs. Holmes darted up, and I followed him. He pushed open a half-closed

door, and we both stood appalled at the sight before us. He opened the door, and we stepped into the hall. The droning

sound swelled louder upon our ears until it became one long, deep wail of distress. It

came from upstairs. Holmes darted up, and I followed him. He pushed open a half-closed

door, and we both stood appalled at the sight before us.

A woman, young and beautiful, was lying dead upon the bed. Her

calm, pale face, with dim, wide-opened blue eyes, looked upward from amid a great tangle

of golden hair. At the foot of the bed, half sitting, half kneeling, his face buried in

the clothes, was a young man, whose frame was racked by his sobs. So absorbed was he by

his bitter grief, that he never looked up until Holmes’s hand was on his shoulder. A woman, young and beautiful, was lying dead upon the bed. Her

calm, pale face, with dim, wide-opened blue eyes, looked upward from amid a great tangle

of golden hair. At the foot of the bed, half sitting, half kneeling, his face buried in

the clothes, was a young man, whose frame was racked by his sobs. So absorbed was he by

his bitter grief, that he never looked up until Holmes’s hand was on his shoulder.

“Are you Mr. Godfrey Staunton?” “Are you Mr. Godfrey Staunton?”

“Yes, yes, I am–but you are too late. She is

dead.” “Yes, yes, I am–but you are too late. She is

dead.”

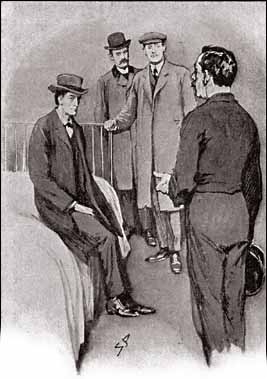

The man was so dazed that he could not be made to understand

that we were anything but doctors who had been sent to his assistance. Holmes was

endeavouring to utter a few words of consolation and to explain the alarm which had been

caused to his friends by his sudden disappearance when there was a step upon the stairs,

and there was the heavy, stern, questioning face of Dr. Armstrong at the door. The man was so dazed that he could not be made to understand

that we were anything but doctors who had been sent to his assistance. Holmes was

endeavouring to utter a few words of consolation and to explain the alarm which had been

caused to his friends by his sudden disappearance when there was a step upon the stairs,

and there was the heavy, stern, questioning face of Dr. Armstrong at the door.

“So, gentlemen,” said he, “you have attained

your end and have certainly chosen a particularly delicate moment for your intrusion. I

would not brawl in the presence of death, but I can assure you that if I were a younger

man your monstrous conduct would not pass with impunity.” “So, gentlemen,” said he, “you have attained

your end and have certainly chosen a particularly delicate moment for your intrusion. I

would not brawl in the presence of death, but I can assure you that if I were a younger

man your monstrous conduct would not pass with impunity.”

“Excuse me, Dr. Armstrong, I think we are a little at

cross-purposes,” said my friend, with dignity. “If you could step downstairs

with us, we may each be able to give some light to the other upon this miserable

affair.” “Excuse me, Dr. Armstrong, I think we are a little at

cross-purposes,” said my friend, with dignity. “If you could step downstairs

with us, we may each be able to give some light to the other upon this miserable

affair.”

A minute later, the grim doctor and ourselves were in the

sitting-room below. A minute later, the grim doctor and ourselves were in the

sitting-room below.

[635] “Well,

sir?” said he. [635] “Well,

sir?” said he.

“I wish you to understand, in the first place, that I am

not employed by Lord Mount-James, and that my sympathies in this matter are entirely

against that nobleman. When a man is lost it is my duty to ascertain his fate, but having

done so the matter ends so far as I am concerned, and so long as there is nothing criminal

I am much more anxious to hush up private scandals than to give them publicity. If, as I

imagine, there is no breach of the law in this matter, you can absolutely depend upon my

discretion and my cooperation in keeping the facts out of the papers.” “I wish you to understand, in the first place, that I am

not employed by Lord Mount-James, and that my sympathies in this matter are entirely

against that nobleman. When a man is lost it is my duty to ascertain his fate, but having