|

|

“ ‘Then take the treaty and lock it up there. I

shall give directions that you may remain behind when the others go, so that you may copy

it at your leisure without fear of being overlooked. When you have finished, relock both

the original and the draft in the desk, and hand them over to me personally to-morrow

morning.’ “ ‘Then take the treaty and lock it up there. I

shall give directions that you may remain behind when the others go, so that you may copy

it at your leisure without fear of being overlooked. When you have finished, relock both

the original and the draft in the desk, and hand them over to me personally to-morrow

morning.’

“I took the papers and– –” “I took the papers and– –”

“Excuse me an instant,” said Holmes. “Were you

alone during this conversation?” “Excuse me an instant,” said Holmes. “Were you

alone during this conversation?”

“Absolutely.” “Absolutely.”

“In a large room?” “In a large room?”

“Thirty feet each way.” “Thirty feet each way.”

“In the centre?” “In the centre?”

“Yes, about it.” “Yes, about it.”

“And speaking low?” “And speaking low?”

“My uncle’s voice is always remarkably low. I hardly

spoke at all.” “My uncle’s voice is always remarkably low. I hardly

spoke at all.”

“Thank you,” said Holmes, shutting his eyes;

“pray go on.” “Thank you,” said Holmes, shutting his eyes;

“pray go on.”

“I did exactly what he indicated and waited until the

other clerks had departed. One of them in my room, Charles Gorot, had some arrears of work

to make up, so I left him there and went out to dine. When I returned he was gone. I was

anxious to hurry my work, for I knew that Joseph–the Mr. Harrison whom you saw just

now–was in town, and that he would travel down to Woking by the eleven-o’clock

train, and I wanted if possible to catch it. “I did exactly what he indicated and waited until the

other clerks had departed. One of them in my room, Charles Gorot, had some arrears of work

to make up, so I left him there and went out to dine. When I returned he was gone. I was

anxious to hurry my work, for I knew that Joseph–the Mr. Harrison whom you saw just

now–was in town, and that he would travel down to Woking by the eleven-o’clock

train, and I wanted if possible to catch it.

“When I came to examine the treaty I saw at once that it

was of such importance that my uncle had been guilty of no exaggeration in what he said.

Without going into details, I may say that it defined the position of Great Britain

towards the Triple Alliance, and foreshadowed the policy which this country would pursue

in the event of the French fleet gaining a complete ascendency over that of Italy in the

Mediterranean. The questions treated in it were purely naval. At the end were the

signatures of the high dignitaries who had signed it. I glanced my eyes over it, and then

settled down to my task of copying. “When I came to examine the treaty I saw at once that it

was of such importance that my uncle had been guilty of no exaggeration in what he said.

Without going into details, I may say that it defined the position of Great Britain

towards the Triple Alliance, and foreshadowed the policy which this country would pursue

in the event of the French fleet gaining a complete ascendency over that of Italy in the

Mediterranean. The questions treated in it were purely naval. At the end were the

signatures of the high dignitaries who had signed it. I glanced my eyes over it, and then

settled down to my task of copying.

“It was a long document, written in the French language,

and containing twenty-six separate articles. I copied as quickly as I could, but at nine

o’clock I had only done nine articles, and it seemed hopeless for me to attempt to

catch my train. I was feeling drowsy and stupid, partly from my dinner and also from the

effects of a long day’s work. A cup of coffee would clear my brain. A commissionaire

remains all night in a little lodge at the foot of the stairs and is in the habit of

making coffee at his spirit-lamp for any of the officials who may be working overtime. I

rang the bell, therefore, to summon him. “It was a long document, written in the French language,

and containing twenty-six separate articles. I copied as quickly as I could, but at nine

o’clock I had only done nine articles, and it seemed hopeless for me to attempt to

catch my train. I was feeling drowsy and stupid, partly from my dinner and also from the

effects of a long day’s work. A cup of coffee would clear my brain. A commissionaire

remains all night in a little lodge at the foot of the stairs and is in the habit of

making coffee at his spirit-lamp for any of the officials who may be working overtime. I

rang the bell, therefore, to summon him.

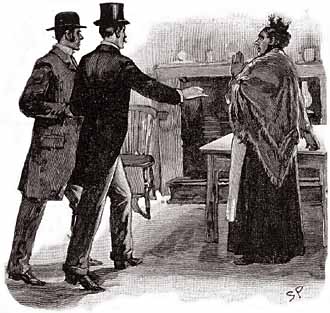

[451] “To

my surprise, it was a woman who answered the summons, a large, coarse-faced, elderly

woman, in an apron. She explained that she was the commissionaire’s wife, who did the

charing, and I gave her the order for the coffee. [451] “To

my surprise, it was a woman who answered the summons, a large, coarse-faced, elderly

woman, in an apron. She explained that she was the commissionaire’s wife, who did the

charing, and I gave her the order for the coffee.

“I wrote two more articles, and then, feeling more drowsy

than ever, I rose and walked up and down the room to stretch my legs. My coffee had not

yet come, and I wondered what the cause of the delay could be. Opening the door, I started

down the corridor to find out. There was a straight passage, dimly lighted, which led from

the room in which I had been working, and was the only exit from it. It ended in a curving

staircase, with the commissionaire’s lodge in the passage at the bottom. Halfway down

this staircase is a small landing, with another passage running into it at right angles.

This second one leads by means of a second small stair to a side door, used by servants,

and also as a short cut by clerks when coming from Charles Street. Here is a rough chart

of the place.” “I wrote two more articles, and then, feeling more drowsy

than ever, I rose and walked up and down the room to stretch my legs. My coffee had not

yet come, and I wondered what the cause of the delay could be. Opening the door, I started

down the corridor to find out. There was a straight passage, dimly lighted, which led from

the room in which I had been working, and was the only exit from it. It ended in a curving

staircase, with the commissionaire’s lodge in the passage at the bottom. Halfway down

this staircase is a small landing, with another passage running into it at right angles.

This second one leads by means of a second small stair to a side door, used by servants,

and also as a short cut by clerks when coming from Charles Street. Here is a rough chart

of the place.”

“Thank you. I think that I quite follow you,”

said Sherlock Holmes. “Thank you. I think that I quite follow you,”

said Sherlock Holmes.

“It is of the utmost importance that you should notice

this point. I went down the stairs and into the hall, where I found the commissionaire

fast asleep in his box, with the kettle boiling furiously upon the spirit-lamp. I took off

the kettle and blew out the lamp, for the water was spurting over the floor. Then I put

out my hand and was about to shake the man, who was still sleeping soundly, when a bell

over his head rang loudly, and he woke with a start. “It is of the utmost importance that you should notice

this point. I went down the stairs and into the hall, where I found the commissionaire

fast asleep in his box, with the kettle boiling furiously upon the spirit-lamp. I took off

the kettle and blew out the lamp, for the water was spurting over the floor. Then I put

out my hand and was about to shake the man, who was still sleeping soundly, when a bell

over his head rang loudly, and he woke with a start.

“ ‘Mr. Phelps, sir!’ said he, looking at me

in bewilderment. “ ‘Mr. Phelps, sir!’ said he, looking at me

in bewilderment.

“ ‘I came down to see if my coffee was ready.’ “ ‘I came down to see if my coffee was ready.’

“ ‘I was boiling the kettle when I fell asleep,

sir.’ He looked at me and then up at the still quivering bell with an ever-growing

astonishment upon his face. “ ‘I was boiling the kettle when I fell asleep,

sir.’ He looked at me and then up at the still quivering bell with an ever-growing

astonishment upon his face.

“ ‘If you was here, sir, then who rang the

bell?’ he asked. “ ‘If you was here, sir, then who rang the

bell?’ he asked.

“ ‘The bell!’ I cried. ‘What bell is

it?’ “ ‘The bell!’ I cried. ‘What bell is

it?’

“ ‘It’s the bell of the room you were working

in.’ “ ‘It’s the bell of the room you were working

in.’

“A cold hand seemed to close round my heart. Someone,

then, was in that room where my precious treaty lay upon the table. I ran frantically up

the stair and along the passage. There was no one in the corridors, Mr. Holmes. There was

no one in the room. All was exactly as I left it, save only that the papers which had been

committed to my care had been taken from the desk on which they lay. The copy was there,

and the original was gone.” “A cold hand seemed to close round my heart. Someone,

then, was in that room where my precious treaty lay upon the table. I ran frantically up

the stair and along the passage. There was no one in the corridors, Mr. Holmes. There was

no one in the room. All was exactly as I left it, save only that the papers which had been

committed to my care had been taken from the desk on which they lay. The copy was there,

and the original was gone.”

[452] Holmes

sat up in his chair and rubbed his hands. I could see that the problem was entirely to his

heart. “Pray, what did you do then?” he murmured. [452] Holmes

sat up in his chair and rubbed his hands. I could see that the problem was entirely to his

heart. “Pray, what did you do then?” he murmured.

“I recognized in an instant that the thief must have come

up the stairs from the side door. Of course I must have met him if he had come the other

way.” “I recognized in an instant that the thief must have come

up the stairs from the side door. Of course I must have met him if he had come the other

way.”

“You were satisfied that he could not have been concealed

in the room all the time, or in the corridor which you have just described as dimly

lighted?” “You were satisfied that he could not have been concealed

in the room all the time, or in the corridor which you have just described as dimly

lighted?”

“It is absolutely impossible. A rat could not conceal

himself either in the room or the corridor. There is no cover at all.” “It is absolutely impossible. A rat could not conceal

himself either in the room or the corridor. There is no cover at all.”

“Thank you. Pray proceed.” “Thank you. Pray proceed.”

“The commissionaire, seeing by my pale face that

something was to be feared, had followed me upstairs. Now we both rushed along the

corridor and down the steep steps which led to Charles Street. The door at the bottom was

closed but unlocked. We flung it open and rushed out. I can distinctly remember that as we

did so there came three chimes from a neighbouring clock. It was a quarter to ten.” “The commissionaire, seeing by my pale face that

something was to be feared, had followed me upstairs. Now we both rushed along the

corridor and down the steep steps which led to Charles Street. The door at the bottom was

closed but unlocked. We flung it open and rushed out. I can distinctly remember that as we

did so there came three chimes from a neighbouring clock. It was a quarter to ten.”

“That is of enormous importance,” said Holmes,

making a note upon his shirt-cuff. “That is of enormous importance,” said Holmes,

making a note upon his shirt-cuff.

“The night was very dark, and a thin, warm rain was

falling. There was no one in Charles Street, but a great traffic was going on, as usual,

in Whitehall, at the extremity. We rushed along the pavement, bare-headed as we were, and

at the far corner we found a policeman standing. “The night was very dark, and a thin, warm rain was

falling. There was no one in Charles Street, but a great traffic was going on, as usual,

in Whitehall, at the extremity. We rushed along the pavement, bare-headed as we were, and

at the far corner we found a policeman standing.

“ ‘A robbery has been committed,’ I gasped.

‘A document of immense value has been stolen from the Foreign Office. Has anyone

passed this way?’ “ ‘A robbery has been committed,’ I gasped.

‘A document of immense value has been stolen from the Foreign Office. Has anyone

passed this way?’

“ ‘I have been standing here for a quarter of an

hour, sir,’ said he, ‘only one person has passed during that time–a woman,

tall and elderly, with a Paisley shawl.’ “ ‘I have been standing here for a quarter of an

hour, sir,’ said he, ‘only one person has passed during that time–a woman,

tall and elderly, with a Paisley shawl.’

“ ‘Ah, that is only my wife,’ cried the

commissionaire; ‘has no one else passed?’ “ ‘Ah, that is only my wife,’ cried the

commissionaire; ‘has no one else passed?’

“ ‘No one.’ “ ‘No one.’

“ ‘Then it must be the other way that the thief

took,’ cried the fellow, tugging at my sleeve. “ ‘Then it must be the other way that the thief

took,’ cried the fellow, tugging at my sleeve.

“But I was not satisfied, and the attempts which he made

to draw me away increased my suspicions. “But I was not satisfied, and the attempts which he made

to draw me away increased my suspicions.

“ ‘Which way did the woman go?’ I cried. “ ‘Which way did the woman go?’ I cried.

“ ‘I don’t know, sir. I noticed her pass, but I

had no special reason for watching her. She seemed to be in a hurry.’ “ ‘I don’t know, sir. I noticed her pass, but I

had no special reason for watching her. She seemed to be in a hurry.’

“ ‘How long ago was it?’ “ ‘How long ago was it?’

“ ‘Oh, not very many minutes.’ “ ‘Oh, not very many minutes.’

“ ‘Within the last five?’ “ ‘Within the last five?’

“ ‘Well, it could not be more than five.’ “ ‘Well, it could not be more than five.’

“ ‘You’re only wasting your time, sir, and

every minute now is of importance,’ cried the commissionaire; ‘take my word for

it that my old woman has nothing to do with it and come down to the other end of the

street. Well, if you won’t, I will.’ And with that he rushed off in the other

direction. “ ‘You’re only wasting your time, sir, and

every minute now is of importance,’ cried the commissionaire; ‘take my word for

it that my old woman has nothing to do with it and come down to the other end of the

street. Well, if you won’t, I will.’ And with that he rushed off in the other

direction.

“But I was after him in an instant and caught him by the

sleeve. “But I was after him in an instant and caught him by the

sleeve.

“ ‘Where do you live?’ said I. “ ‘Where do you live?’ said I.

“ ‘16 Ivy Lane, Brixton,’ he answered.

‘But don’t let yourself be drawn away upon a false scent, Mr. Phelps. Come to

the other end of the street and let us see if we can hear of anything.’ “ ‘16 Ivy Lane, Brixton,’ he answered.

‘But don’t let yourself be drawn away upon a false scent, Mr. Phelps. Come to

the other end of the street and let us see if we can hear of anything.’

“Nothing was to be lost by following his advice. With the

policeman we both hurried down, but only to find the street full of traffic, many people

coming and [453] going, but

all only too eager to get to a place of safety upon so wet a night. There was no lounger

who could tell us who had passed. “Nothing was to be lost by following his advice. With the

policeman we both hurried down, but only to find the street full of traffic, many people

coming and [453] going, but

all only too eager to get to a place of safety upon so wet a night. There was no lounger

who could tell us who had passed.

“Then we returned to the office and searched the stairs

and the passage without result. The corridor which led to the room was laid down with a

kind of creamy linoleum which shows an impression very easily. We examined it very

carefully, but found no outline of any footmark.” “Then we returned to the office and searched the stairs

and the passage without result. The corridor which led to the room was laid down with a

kind of creamy linoleum which shows an impression very easily. We examined it very

carefully, but found no outline of any footmark.”

“Had it been raining all evening?” “Had it been raining all evening?”

“Since about seven.” “Since about seven.”

“How is it, then, that the woman who came into the room

about nine left no traces with her muddy boots?” “How is it, then, that the woman who came into the room

about nine left no traces with her muddy boots?”

“I am glad you raised the point. It occurred to me at the

time. The charwomen are in the habit of taking off their boots at the

commissionaire’s office, and putting on list slippers.” “I am glad you raised the point. It occurred to me at the

time. The charwomen are in the habit of taking off their boots at the

commissionaire’s office, and putting on list slippers.”

“That is very clear. There were no marks, then, though

the night was a wet one? The chain of events is certainly one of extraordinary interest.

What did you do next?” “That is very clear. There were no marks, then, though

the night was a wet one? The chain of events is certainly one of extraordinary interest.

What did you do next?”

“We examined the room also. There is no possibility of a

secret door, and the windows are quite thirty feet from the ground. Both of them were

fastened on the inside. The carpet prevents any possibility of a trapdoor, and the ceiling

is of the ordinary whitewashed kind. I will pledge my life that whoever stole my papers

could only have come through the door.” “We examined the room also. There is no possibility of a

secret door, and the windows are quite thirty feet from the ground. Both of them were

fastened on the inside. The carpet prevents any possibility of a trapdoor, and the ceiling

is of the ordinary whitewashed kind. I will pledge my life that whoever stole my papers

could only have come through the door.”

“How about the fireplace?” “How about the fireplace?”

“They use none. There is a stove. The bell-rope hangs

from the wire just to the right of my desk. Whoever rang it must have come right up to the

desk to do it. But why should any criminal wish to ring the bell? It is a most insoluble

mystery.” “They use none. There is a stove. The bell-rope hangs

from the wire just to the right of my desk. Whoever rang it must have come right up to the

desk to do it. But why should any criminal wish to ring the bell? It is a most insoluble

mystery.”

“Certainly the incident was unusual. What were your next

steps? You examined the room, I presume, to see if the intruder had left any

traces–any cigar-end or dropped glove or hairpin or other trifle?” “Certainly the incident was unusual. What were your next

steps? You examined the room, I presume, to see if the intruder had left any

traces–any cigar-end or dropped glove or hairpin or other trifle?”

“There was nothing of the sort.” “There was nothing of the sort.”

“No smell?” “No smell?”

“Well, we never thought of that.” “Well, we never thought of that.”

“Ah, a scent of tobacco would have been worth a great

deal to us in such an investigation.” “Ah, a scent of tobacco would have been worth a great

deal to us in such an investigation.”

“I never smoke myself, so I think I should have observed

it if there had been any smell of tobacco. There was absolutely no clue of any kind. The

only tangible fact was that the commissionaire’s wife–Mrs. Tangey was the

name–had hurried out of the place. He could give no explanation save that it was

about the time when the woman always went home. The policeman and I agreed that our best

plan would be to seize the woman before she could get rid of the papers, presuming that

she had them. “I never smoke myself, so I think I should have observed

it if there had been any smell of tobacco. There was absolutely no clue of any kind. The

only tangible fact was that the commissionaire’s wife–Mrs. Tangey was the

name–had hurried out of the place. He could give no explanation save that it was

about the time when the woman always went home. The policeman and I agreed that our best

plan would be to seize the woman before she could get rid of the papers, presuming that

she had them.

“The alarm had reached Scotland Yard by this time, and

Mr. Forbes, the detective, came round at once and took up the case with a great deal of

energy. We hired a hansom, and in half an hour we were at the address which had been given

to us. A young woman opened the door, who proved to be Mrs. Tangey’s eldest daughter.

Her mother had not come back yet, and we were shown into the front room to wait. “The alarm had reached Scotland Yard by this time, and

Mr. Forbes, the detective, came round at once and took up the case with a great deal of

energy. We hired a hansom, and in half an hour we were at the address which had been given

to us. A young woman opened the door, who proved to be Mrs. Tangey’s eldest daughter.

Her mother had not come back yet, and we were shown into the front room to wait.

“About ten minutes later a knock came at the door, and

here we made the one serious mistake for which I blame myself. Instead of opening the door

ourselves, we allowed the girl to do so. We heard her say, ‘Mother, there are two men

in the [454] house waiting

to see you,’ and an instant afterwards we heard the patter of feet rushing down the

passage. Forbes flung open the door, and we both ran into the back room or kitchen, but

the woman had got there before us. She stared at us with defiant eyes, and then, suddenly

recognizing me, an expression of absolute astonishment came over her face. “About ten minutes later a knock came at the door, and

here we made the one serious mistake for which I blame myself. Instead of opening the door

ourselves, we allowed the girl to do so. We heard her say, ‘Mother, there are two men

in the [454] house waiting

to see you,’ and an instant afterwards we heard the patter of feet rushing down the

passage. Forbes flung open the door, and we both ran into the back room or kitchen, but

the woman had got there before us. She stared at us with defiant eyes, and then, suddenly

recognizing me, an expression of absolute astonishment came over her face.

“ ‘Why, if it isn’t Mr. Phelps, of the

office!’ she cried. “ ‘Why, if it isn’t Mr. Phelps, of the

office!’ she cried.

“ ‘Come, come, who did you think we were when you

ran away from us?’ asked my companion. “ ‘Come, come, who did you think we were when you

ran away from us?’ asked my companion.

“ ‘I thought you were the brokers,’ said she,

‘we have had some trouble with a tradesman.’ “ ‘I thought you were the brokers,’ said she,

‘we have had some trouble with a tradesman.’

“ ‘That’s not quite good enough,’ answered

Forbes. ‘We have reason to believe that you have taken a paper of importance from the

Foreign Office, and that you ran in here to dispose of it. You must come back with us to

Scotland Yard to be searched.’ “ ‘That’s not quite good enough,’ answered

Forbes. ‘We have reason to believe that you have taken a paper of importance from the

Foreign Office, and that you ran in here to dispose of it. You must come back with us to

Scotland Yard to be searched.’

“It was in vain that she protested and resisted. A

four-wheeler was brought, and we all three drove back in it. We had first made an

examination of the kitchen, and especially of the kitchen fire, to see whether she might

have made away with the papers during the instant that she was alone. There were no signs,

however, of any ashes or scraps. When we reached Scotland Yard she was handed over at once

to the female searcher. I waited in an agony of suspense until she came back with her

report. There were no signs of the papers. “It was in vain that she protested and resisted. A

four-wheeler was brought, and we all three drove back in it. We had first made an

examination of the kitchen, and especially of the kitchen fire, to see whether she might

have made away with the papers during the instant that she was alone. There were no signs,

however, of any ashes or scraps. When we reached Scotland Yard she was handed over at once

to the female searcher. I waited in an agony of suspense until she came back with her

report. There were no signs of the papers.

“Then for the first time the horror of my situation came

in its full force. Hitherto I had been acting, and action had numbed thought. I had been

so confident of regaining the treaty at once that I had not dared to think of what would

be the consequence if I failed to do so. But now there was nothing more to be done, and I

had leisure to realize my position. It was horrible. Watson there would tell you that I

was a nervous, sensitive boy at school. It is my nature. I thought of my uncle and of his

colleagues in the Cabinet, of the shame which I had brought upon him, upon myself, upon

everyone connected with me. What though I was the victim of an extraordinary accident? No

allowance is made for accidents where diplomatic interests are at stake. I was ruined,

shamefully, hopelessly ruined. I don’t know what I did. I fancy I must have made a

scene. I have a dim recollection of a group of officials who crowded round me,

endeavouring to soothe me. One of them drove down with me to Waterloo, and saw me into the

Woking train. I believe that he would have come all the way had it not been that Dr.

Ferrier, who lives near me, was going down by that very train. The doctor most kindly took

charge of me, and it was well he did so, for I had a fit in the station, and before we

reached home I was practically a raving maniac. “Then for the first time the horror of my situation came

in its full force. Hitherto I had been acting, and action had numbed thought. I had been

so confident of regaining the treaty at once that I had not dared to think of what would

be the consequence if I failed to do so. But now there was nothing more to be done, and I

had leisure to realize my position. It was horrible. Watson there would tell you that I

was a nervous, sensitive boy at school. It is my nature. I thought of my uncle and of his

colleagues in the Cabinet, of the shame which I had brought upon him, upon myself, upon

everyone connected with me. What though I was the victim of an extraordinary accident? No

allowance is made for accidents where diplomatic interests are at stake. I was ruined,

shamefully, hopelessly ruined. I don’t know what I did. I fancy I must have made a

scene. I have a dim recollection of a group of officials who crowded round me,

endeavouring to soothe me. One of them drove down with me to Waterloo, and saw me into the

Woking train. I believe that he would have come all the way had it not been that Dr.

Ferrier, who lives near me, was going down by that very train. The doctor most kindly took

charge of me, and it was well he did so, for I had a fit in the station, and before we

reached home I was practically a raving maniac.

“You can imagine the state of things here when they were

roused from their beds by the doctor’s ringing and found me in this condition. Poor

Annie here and my mother were broken-hearted. Dr. Ferrier had just heard enough from the

detective at the station to be able to give an idea of what had happened, and his story

did not mend matters. It was evident to all that I was in for a long illness, so Joseph

was bundled out of this cheery bedroom, and it was turned into a sick-room for me. Here I

have lain, Mr. Holmes, for over nine weeks, unconscious, and raving with brain-fever. If

it had not been for Miss Harrison here and for the doctor’s care, I should not be

speaking to you now. She has nursed me by day and a hired nurse has looked after me by

night, for in my mad fits I was capable of anything. Slowly my reason has cleared, but it

is only during the last three days [455] that

my memory has quite returned. Sometimes I wish that it never had. The first thing that I

did was to wire to Mr. Forbes, who had the case in hand. He came out, and assures me that,

though everything has been done, no trace of a clue has been discovered. The

commissionaire and his wife have been examined in every way without any light being thrown

upon the matter. The suspicions of the police then rested upon young Gorot, who, as you

may remember, stayed over-time in the office that night. His remaining behind and his

French name were really the only two points which could suggest suspicion; but, as a

matter of fact, I did not begin work until he had gone, and his people are of Huguenot

extraction, but as English in sympathy and tradition as you and I are. Nothing was found

to implicate him in any way, and there the matter dropped. I turn to you, Mr. Holmes, as

absolutely my last hope. If you fail me, then my honour as well as my position are forever

forfeited.” “You can imagine the state of things here when they were

roused from their beds by the doctor’s ringing and found me in this condition. Poor

Annie here and my mother were broken-hearted. Dr. Ferrier had just heard enough from the

detective at the station to be able to give an idea of what had happened, and his story

did not mend matters. It was evident to all that I was in for a long illness, so Joseph

was bundled out of this cheery bedroom, and it was turned into a sick-room for me. Here I

have lain, Mr. Holmes, for over nine weeks, unconscious, and raving with brain-fever. If

it had not been for Miss Harrison here and for the doctor’s care, I should not be

speaking to you now. She has nursed me by day and a hired nurse has looked after me by

night, for in my mad fits I was capable of anything. Slowly my reason has cleared, but it

is only during the last three days [455] that

my memory has quite returned. Sometimes I wish that it never had. The first thing that I

did was to wire to Mr. Forbes, who had the case in hand. He came out, and assures me that,

though everything has been done, no trace of a clue has been discovered. The

commissionaire and his wife have been examined in every way without any light being thrown

upon the matter. The suspicions of the police then rested upon young Gorot, who, as you

may remember, stayed over-time in the office that night. His remaining behind and his

French name were really the only two points which could suggest suspicion; but, as a

matter of fact, I did not begin work until he had gone, and his people are of Huguenot

extraction, but as English in sympathy and tradition as you and I are. Nothing was found

to implicate him in any way, and there the matter dropped. I turn to you, Mr. Holmes, as

absolutely my last hope. If you fail me, then my honour as well as my position are forever

forfeited.”

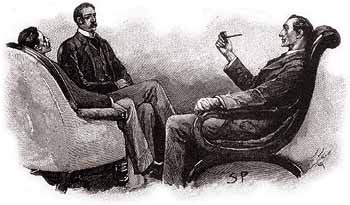

The invalid sank back upon his cushions, tired out by this

long recital, while his nurse poured him out a glass of some stimulating medicine. Holmes

sat silently, with his head thrown back and his eyes closed, in an attitude which might

seem listless to a stranger, but which I knew betokened the most intense self-absorption. The invalid sank back upon his cushions, tired out by this

long recital, while his nurse poured him out a glass of some stimulating medicine. Holmes

sat silently, with his head thrown back and his eyes closed, in an attitude which might

seem listless to a stranger, but which I knew betokened the most intense self-absorption.

“Your statement has been so explicit,” said he at

last, “that you have really left me very few questions to ask. There is one of the

very utmost importance, however. Did you tell anyone that you had this special task to

perform?” “Your statement has been so explicit,” said he at

last, “that you have really left me very few questions to ask. There is one of the

very utmost importance, however. Did you tell anyone that you had this special task to

perform?”

“No one.” “No one.”

“Not Miss Harrison here, for example?” “Not Miss Harrison here, for example?”

“No. I had not been back to Woking between getting the

order and executing the commission.” “No. I had not been back to Woking between getting the

order and executing the commission.”

“And none of your people had by chance been to see

you?” “And none of your people had by chance been to see

you?”

“None.” “None.”

“Did any of them know their way about in the

office?” “Did any of them know their way about in the

office?”

“Oh, yes, all of them had been shown over it.” “Oh, yes, all of them had been shown over it.”

“Still, of course, if you said nothing to anyone about

the treaty these inquiries are irrelevant.” “Still, of course, if you said nothing to anyone about

the treaty these inquiries are irrelevant.”

“I said nothing.” “I said nothing.”

“Do you know anything of the commissionaire?” “Do you know anything of the commissionaire?”

“Nothing except that he is an old soldier.” “Nothing except that he is an old soldier.”

“What regiment?” “What regiment?”

“Oh, I have heard–Coldstream Guards.” “Oh, I have heard–Coldstream Guards.”

“Thank you. I have no doubt I can get details from

Forbes. The authorities are excellent at amassing facts, though they do not always use

them to advantage. What a lovely thing a rose is!” “Thank you. I have no doubt I can get details from

Forbes. The authorities are excellent at amassing facts, though they do not always use

them to advantage. What a lovely thing a rose is!”

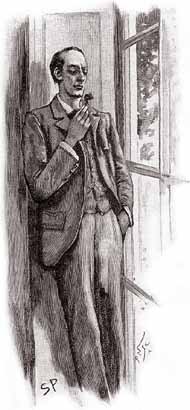

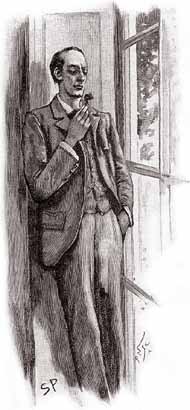

He walked past the couch to the open window and held up the

drooping stalk of a moss-rose, looking down at the dainty blend of crimson and green. It

was a new phase of his character to me, for I had never before seen him show any keen

interest in natural objects. He walked past the couch to the open window and held up the

drooping stalk of a moss-rose, looking down at the dainty blend of crimson and green. It

was a new phase of his character to me, for I had never before seen him show any keen

interest in natural objects.

“There is nothing in which deduction is so necessary as

in religion,” said he, leaning with his back against the shutters. “It can be

built up as an exact science by the reasoner. Our highest assurance of the goodness of

Providence seems to me to rest in the flowers. All other things, our powers, our desires,

our food, are all really necessary for our existence in the first instance. But this rose

is an extra. Its smell and its colour are an embellishment of life, not a condition of it.

It is only [456] goodness

which gives extras, and so I say again that we have much to hope from the flowers.” “There is nothing in which deduction is so necessary as

in religion,” said he, leaning with his back against the shutters. “It can be

built up as an exact science by the reasoner. Our highest assurance of the goodness of

Providence seems to me to rest in the flowers. All other things, our powers, our desires,

our food, are all really necessary for our existence in the first instance. But this rose

is an extra. Its smell and its colour are an embellishment of life, not a condition of it.

It is only [456] goodness

which gives extras, and so I say again that we have much to hope from the flowers.”

Percy Phelps and his nurse looked at Holmes during this

demonstration with surprise and a good deal of disappointment written upon their faces. He

had fallen into a reverie, with the moss-rose between his fingers. It had lasted some

minutes before the young lady broke in upon it. Percy Phelps and his nurse looked at Holmes during this

demonstration with surprise and a good deal of disappointment written upon their faces. He

had fallen into a reverie, with the moss-rose between his fingers. It had lasted some

minutes before the young lady broke in upon it.

“Do you see any prospect of solving this mystery, Mr.

Holmes?” she asked with a touch of asperity in her voice. “Do you see any prospect of solving this mystery, Mr.

Holmes?” she asked with a touch of asperity in her voice.

“Oh, the mystery!” he answered, coming back with a

start to the realities of life. “Well, it would be absurd to deny that the case is a

very abstruse and complicated one, but I can promise you that I will look into the matter

and let you know any points which may strike me.” “Oh, the mystery!” he answered, coming back with a

start to the realities of life. “Well, it would be absurd to deny that the case is a

very abstruse and complicated one, but I can promise you that I will look into the matter

and let you know any points which may strike me.”

“Do you see any clue?” “Do you see any clue?”

“You have furnished me with seven, but of course I must

test them before I can pronounce upon their value.” “You have furnished me with seven, but of course I must

test them before I can pronounce upon their value.”

“You suspect someone?” “You suspect someone?”

“I suspect myself.” “I suspect myself.”

“What!” “What!”

“Of coming to conclusions too rapidly.” “Of coming to conclusions too rapidly.”

“Then go to London and test your conclusions.” “Then go to London and test your conclusions.”

“Your advice is very excellent, Miss Harrison,” said

Holmes, rising. “I think, Watson, we cannot do better. Do not allow yourself to

indulge in false hopes, Mr. Phelps. The affair is a very tangled one.” “Your advice is very excellent, Miss Harrison,” said

Holmes, rising. “I think, Watson, we cannot do better. Do not allow yourself to

indulge in false hopes, Mr. Phelps. The affair is a very tangled one.”

“I shall be in a fever until I see you again,” cried

the diplomatist. “I shall be in a fever until I see you again,” cried

the diplomatist.

“Well, I’ll come out by the same train to-morrow,

though it’s more than likely that my report will be a negative one.” “Well, I’ll come out by the same train to-morrow,

though it’s more than likely that my report will be a negative one.”

“God bless you for promising to come,” cried our

client. “It gives me fresh life to know that something is being done. By the way, I

have had a letter from Lord Holdhurst.” “God bless you for promising to come,” cried our

client. “It gives me fresh life to know that something is being done. By the way, I

have had a letter from Lord Holdhurst.”

“Ha! what did he say?” “Ha! what did he say?”

“He was cold, but not harsh. I dare say my severe illness

prevented him from being that. He repeated that the matter was of the utmost importance,

and added that no steps would be taken about my future–by which he means, of course,

my dismissal–until my health was restored and I had an opportunity of repairing my

misfortune.” “He was cold, but not harsh. I dare say my severe illness

prevented him from being that. He repeated that the matter was of the utmost importance,

and added that no steps would be taken about my future–by which he means, of course,

my dismissal–until my health was restored and I had an opportunity of repairing my

misfortune.”

“Well, that was reasonable and considerate,” said

Holmes. “Come, Watson, for we have a good day’s work before us in town.” “Well, that was reasonable and considerate,” said

Holmes. “Come, Watson, for we have a good day’s work before us in town.”

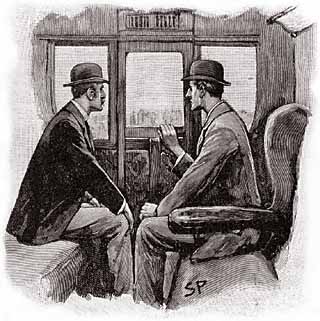

Mr. Joseph Harrison drove us down to the station, and we were

soon whirling up in a Portsmouth train. Holmes was sunk in profound thought and hardly

opened his mouth until we had passed Clapham Junction. Mr. Joseph Harrison drove us down to the station, and we were

soon whirling up in a Portsmouth train. Holmes was sunk in profound thought and hardly

opened his mouth until we had passed Clapham Junction.

“It’s a very cheery thing to come into London by any

of these lines which run high and allow you to look down upon the houses like this.” “It’s a very cheery thing to come into London by any

of these lines which run high and allow you to look down upon the houses like this.”

I thought he was joking, for the view was sordid enough,

but he soon explained himself. I thought he was joking, for the view was sordid enough,

but he soon explained himself.

“Look at those big, isolated clumps of buildings rising

up above the slates, like brick islands in a lead-coloured sea.” “Look at those big, isolated clumps of buildings rising

up above the slates, like brick islands in a lead-coloured sea.”

“The board-schools.” “The board-schools.”

“Light-houses, my boy! Beacons of the future! Capsules

with hundreds of bright [457] little

seeds in each, out of which will spring the wiser, better England of the future. I suppose

that man Phelps does not drink?” “Light-houses, my boy! Beacons of the future! Capsules

with hundreds of bright [457] little

seeds in each, out of which will spring the wiser, better England of the future. I suppose

that man Phelps does not drink?”

“I should not think so.” “I should not think so.”

“Nor should I, but we are bound to take every possibility

into account. The poor devil has certainly got himself into very deep water, and it’s

a question whether we shall ever be able to get him ashore. What do you think of Miss

Harrison?” “Nor should I, but we are bound to take every possibility

into account. The poor devil has certainly got himself into very deep water, and it’s

a question whether we shall ever be able to get him ashore. What do you think of Miss

Harrison?”

“A girl of strong character.” “A girl of strong character.”

“Yes, but she is a good sort, or I am mistaken. She and

her brother are the only children of an iron-master somewhere up Northumberland way. He

got engaged to her when travelling last winter, and she came down to be introduced to his

people, with her brother as escort. Then came the smash, and she stayed on to nurse her

lover, while brother Joseph, finding himself pretty snug, stayed on, too. I’ve been

making a few independent inquiries, you see. But to-day must be a day of inquiries.” “Yes, but she is a good sort, or I am mistaken. She and

her brother are the only children of an iron-master somewhere up Northumberland way. He

got engaged to her when travelling last winter, and she came down to be introduced to his

people, with her brother as escort. Then came the smash, and she stayed on to nurse her

lover, while brother Joseph, finding himself pretty snug, stayed on, too. I’ve been

making a few independent inquiries, you see. But to-day must be a day of inquiries.”

“My practice– –” I began. “My practice– –” I began.

“Oh, if you find your own cases more interesting than

mine– –” said Holmes with some asperity. “Oh, if you find your own cases more interesting than

mine– –” said Holmes with some asperity.

“I was going to say that my practice could get along very

well for a day or two, since it is the slackest time in the year.” “I was going to say that my practice could get along very

well for a day or two, since it is the slackest time in the year.”

“Excellent,” said he, recovering his good-humour.

“Then we’ll look into this matter together. I think that we should begin by

seeing Forbes. He can probably tell us all the details we want until we know from what

side the case is to be approached.” “Excellent,” said he, recovering his good-humour.

“Then we’ll look into this matter together. I think that we should begin by

seeing Forbes. He can probably tell us all the details we want until we know from what

side the case is to be approached.”

“You said you had a clue?” “You said you had a clue?”

“Well, we have several, but we can only test their value

by further inquiry. The most difficult crime to track is the one which is purposeless. Now

this is not purposeless. Who is it who profits by it? There is the French ambassador,

there is the Russian, there is whoever might sell it to either of these, and there is Lord

Holdhurst.” “Well, we have several, but we can only test their value

by further inquiry. The most difficult crime to track is the one which is purposeless. Now

this is not purposeless. Who is it who profits by it? There is the French ambassador,

there is the Russian, there is whoever might sell it to either of these, and there is Lord

Holdhurst.”

“Lord Holdhurst!” “Lord Holdhurst!”

“Well, it is just conceivable that a statesman might find

himself in a position where he was not sorry to have such a document accidentally

destroyed.” “Well, it is just conceivable that a statesman might find

himself in a position where he was not sorry to have such a document accidentally

destroyed.”

“Not a statesman with the honourable record of Lord

Holdhurst?” “Not a statesman with the honourable record of Lord

Holdhurst?”

“It is a possibility and we cannot afford to disregard

it. We shall see the noble lord to-day and find out if he can tell us anything. Meanwhile

I have already set inquiries on foot.” “It is a possibility and we cannot afford to disregard

it. We shall see the noble lord to-day and find out if he can tell us anything. Meanwhile

I have already set inquiries on foot.”

“Already?” “Already?”

“Yes, I sent wires from Woking station to every evening

paper in London. This advertisement will appear in each of them.” “Yes, I sent wires from Woking station to every evening

paper in London. This advertisement will appear in each of them.”

He handed over a sheet torn from a notebook. On it was

scribbled in pencil: He handed over a sheet torn from a notebook. On it was

scribbled in pencil:

�10 reward. The number of the cab which dropped a fare at

or about the door of the Foreign Office in Charles Street at quarter to ten in the evening

of May 23d. Apply 221B, Baker Street. �10 reward. The number of the cab which dropped a fare at

or about the door of the Foreign Office in Charles Street at quarter to ten in the evening

of May 23d. Apply 221B, Baker Street.

“You are confident that the thief came in a cab?” “You are confident that the thief came in a cab?”

“If not, there is no harm done. But if Mr. Phelps is

correct in stating that there is no hiding-place either in the room or the corridors, then

the person must have come from outside. If he came from outside on so wet a night, and yet

left no trace of damp upon the linoleum, which was examined within a few minutes of [458] his passing, then it is

exceedingly probable that he came in a cab. Yes, I think that we may safely deduce a

cab.” “If not, there is no harm done. But if Mr. Phelps is

correct in stating that there is no hiding-place either in the room or the corridors, then

the person must have come from outside. If he came from outside on so wet a night, and yet

left no trace of damp upon the linoleum, which was examined within a few minutes of [458] his passing, then it is

exceedingly probable that he came in a cab. Yes, I think that we may safely deduce a

cab.”

“It sounds plausible.” “It sounds plausible.”

“That is one of the clues of which I spoke. It may lead

us to something. And then, of course, there is the bell–which is the most distinctive

feature of the case. Why should the bell ring? Was it the thief who did it out of bravado?

Or was it someone who was with the thief who did it in order to prevent the crime? Or was

it an accident? Or was it– –?” He sank back into the state of intense and

silent thought from which he had emerged; but it seemed to me, accustomed as I was to his

every mood, that some new possibility had dawned suddenly upon him. “That is one of the clues of which I spoke. It may lead

us to something. And then, of course, there is the bell–which is the most distinctive

feature of the case. Why should the bell ring? Was it the thief who did it out of bravado?

Or was it someone who was with the thief who did it in order to prevent the crime? Or was

it an accident? Or was it– –?” He sank back into the state of intense and

silent thought from which he had emerged; but it seemed to me, accustomed as I was to his

every mood, that some new possibility had dawned suddenly upon him.

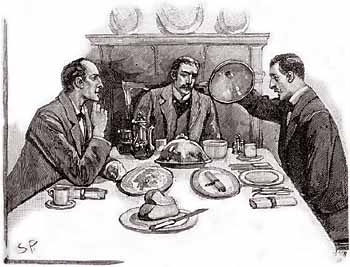

It was twenty past three when we reached our terminus, and

after a hasty luncheon at the buffet we pushed on at once to Scotland Yard. Holmes had

already wired to Forbes, and we found him waiting to receive us–a small, foxy man

with a sharp but by no means amiable expression. He was decidedly frigid in his manner to

us, especially when he heard the errand upon which we had come. It was twenty past three when we reached our terminus, and

after a hasty luncheon at the buffet we pushed on at once to Scotland Yard. Holmes had

already wired to Forbes, and we found him waiting to receive us–a small, foxy man

with a sharp but by no means amiable expression. He was decidedly frigid in his manner to

us, especially when he heard the errand upon which we had come.

“I’ve heard of your methods before now, Mr.

Holmes,” said he tartly. “You are ready enough to use all the information that

the police can lay at your disposal, and then you try to finish the case yourself and

bring discredit on them.” “I’ve heard of your methods before now, Mr.

Holmes,” said he tartly. “You are ready enough to use all the information that

the police can lay at your disposal, and then you try to finish the case yourself and

bring discredit on them.”

“On the contrary,” said Holmes, “out of my last

fifty-three cases my name has only appeared in four, and the police have had all the

credit in forty-nine. I don’t blame you for not knowing this, for you are young and

inexperienced, but if you wish to get on in your new duties you will work with me and not

against me.” “On the contrary,” said Holmes, “out of my last

fifty-three cases my name has only appeared in four, and the police have had all the

credit in forty-nine. I don’t blame you for not knowing this, for you are young and

inexperienced, but if you wish to get on in your new duties you will work with me and not

against me.”

“I’d be very glad of a hint or two,” said the

detective, changing his manner. “I’ve certainly had no credit from the case so

far.” “I’d be very glad of a hint or two,” said the

detective, changing his manner. “I’ve certainly had no credit from the case so

far.”

“What steps have you taken?” “What steps have you taken?”

“Tangey, the commissionaire, has been shadowed. He left

the Guards with a good character, and we can find nothing against him. His wife is a bad

lot, though. I fancy she knows more about this than appears.” “Tangey, the commissionaire, has been shadowed. He left

the Guards with a good character, and we can find nothing against him. His wife is a bad

lot, though. I fancy she knows more about this than appears.”

“Have you shadowed her?” “Have you shadowed her?”

“We have set one of our women on to her. Mrs. Tangey

drinks, and our woman has been with her twice when she was well on, but she could get

nothing out of her.” “We have set one of our women on to her. Mrs. Tangey

drinks, and our woman has been with her twice when she was well on, but she could get

nothing out of her.”

“I understand that they have had brokers in the

house?” “I understand that they have had brokers in the

house?”

“Yes, but they were paid off.” “Yes, but they were paid off.”

“Where did the money come from?” “Where did the money come from?”

“That was all right. His pension was due. They have not

shown any sign of being in funds.” “That was all right. His pension was due. They have not

shown any sign of being in funds.”

“What explanation did she give of having answered the

bell when Mr. Phelps rang for the coffee?” “What explanation did she give of having answered the

bell when Mr. Phelps rang for the coffee?”

“She said that her husband was very tired and she wished

to relieve him.” “She said that her husband was very tired and she wished

to relieve him.”

“Well, certainly that would agree with his being found a

little later asleep in his chair. There is nothing against them then but the woman’s

character. Did you ask her why she hurried away that night? Her haste attracted the

attention of the police constable.” “Well, certainly that would agree with his being found a

little later asleep in his chair. There is nothing against them then but the woman’s

character. Did you ask her why she hurried away that night? Her haste attracted the

attention of the police constable.”

“She was later than usual and wanted to get home.” “She was later than usual and wanted to get home.”

“Did you point out to her that you and Mr. Phelps, who

started at least twenty minutes after her, got home before her?” “Did you point out to her that you and Mr. Phelps, who

started at least twenty minutes after her, got home before her?”

“She explains that by the difference between a ’bus

and a hansom.” “She explains that by the difference between a ’bus

and a hansom.”

[459] “Did

she make it clear why, on reaching her house, she ran into the back kitchen?” [459] “Did

she make it clear why, on reaching her house, she ran into the back kitchen?”

“Because she had the money there with which to pay off

the brokers.” “Because she had the money there with which to pay off

the brokers.”

“She has at least an answer for everything. Did you ask

her whether in leaving she met anyone or saw anyone loitering about Charles Street?” “She has at least an answer for everything. Did you ask

her whether in leaving she met anyone or saw anyone loitering about Charles Street?”

“She saw no one but the constable.” “She saw no one but the constable.”

“Well, you seem to have cross-examined her pretty

thoroughly. What else have you done?” “Well, you seem to have cross-examined her pretty

thoroughly. What else have you done?”

“The clerk Gorot has been shadowed all these nine weeks,

but without result. We can show nothing against him.” “The clerk Gorot has been shadowed all these nine weeks,

but without result. We can show nothing against him.”

“Anything else?” “Anything else?”

“Well, we have nothing else to go upon–no evidence

of any kind.” “Well, we have nothing else to go upon–no evidence

of any kind.”

“Have you formed any theory about how that bell

rang?” “Have you formed any theory about how that bell

rang?”

“Well, I must confess that it beats me. It was a cool

hand, whoever it was, to go and give the alarm like that.” “Well, I must confess that it beats me. It was a cool

hand, whoever it was, to go and give the alarm like that.”

“Yes, it was a queer thing to do. Many thanks to you for

what you have told me. If I can put the man into your hands you shall hear from me. Come

along, Watson.” “Yes, it was a queer thing to do. Many thanks to you for

what you have told me. If I can put the man into your hands you shall hear from me. Come

along, Watson.”

“Where are we going to now?” I asked as we left the

office. “Where are we going to now?” I asked as we left the

office.

“We are now going to interview Lord Holdhurst, the

cabinet minister and future premier of England.” “We are now going to interview Lord Holdhurst, the

cabinet minister and future premier of England.”

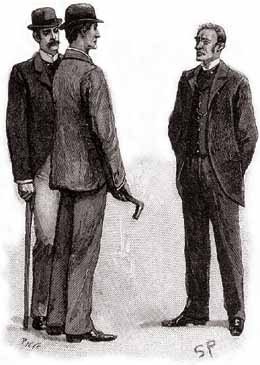

We were fortunate in finding that Lord Holdhurst was still

in his chambers in Downing Street, and on Holmes sending in his card we were instantly

shown up. The statesman received us with that old-fashioned courtesy for which he is

remarkable and seated us on the two luxuriant lounges on either side of the fireplace.

Standing on the rug between us, with his slight, tall figure, his sharp features,

thoughtful face, and curling hair prematurely tinged with gray, he seemed to represent

that not too common type, a nobleman who is in truth noble. We were fortunate in finding that Lord Holdhurst was still

in his chambers in Downing Street, and on Holmes sending in his card we were instantly

shown up. The statesman received us with that old-fashioned courtesy for which he is

remarkable and seated us on the two luxuriant lounges on either side of the fireplace.

Standing on the rug between us, with his slight, tall figure, his sharp features,

thoughtful face, and curling hair prematurely tinged with gray, he seemed to represent

that not too common type, a nobleman who is in truth noble.

“Your name is very familiar to me, Mr. Holmes,”

said he, smiling. “And of course I cannot pretend to be ignorant of the object of

your visit. There has only been one occurrence in these offices which could call for your

attention. In whose interest are you acting, may I ask?” “Your name is very familiar to me, Mr. Holmes,”

said he, smiling. “And of course I cannot pretend to be ignorant of the object of

your visit. There has only been one occurrence in these offices which could call for your

attention. In whose interest are you acting, may I ask?”

“In that of Mr. Percy Phelps,” answered Holmes. “In that of Mr. Percy Phelps,” answered Holmes.

“Ah, my unfortunate nephew! You can understand that our

kinship makes it the more impossible for me to screen him in any way. I fear that the

incident must have a very prejudicial effect upon his career.” “Ah, my unfortunate nephew! You can understand that our

kinship makes it the more impossible for me to screen him in any way. I fear that the

incident must have a very prejudicial effect upon his career.”

“But if the document is found?” “But if the document is found?”

“Ah, that, of course, would be different.” “Ah, that, of course, would be different.”

“I had one or two questions which I wished to ask you,

Lord Holdhurst.” “I had one or two questions which I wished to ask you,

Lord Holdhurst.”

“I shall be happy to give you any information in my

power.” “I shall be happy to give you any information in my

power.”

“Was it in this room that you gave your instructions as

to the copying of the document?” “Was it in this room that you gave your instructions as

to the copying of the document?”

“It was.” “It was.”

“Then you could hardly have been overheard?” “Then you could hardly have been overheard?”

“It is out of the question.” “It is out of the question.”

“Did you ever mention to anyone that it was your

intention to give anyone the treaty to be copied?” “Did you ever mention to anyone that it was your

intention to give anyone the treaty to be copied?”

“Never.” “Never.”

“You are certain of that?” “You are certain of that?”

[460] “Absolutely.” [460] “Absolutely.”

“Well, since you never said so, and Mr. Phelps never said

so, and nobody else knew anything of the matter, then the thief’s presence in the

room was purely accidental. He saw his chance and he took it.” “Well, since you never said so, and Mr. Phelps never said

so, and nobody else knew anything of the matter, then the thief’s presence in the

room was purely accidental. He saw his chance and he took it.”

The statesman smiled. “You take me out of my province

there,” said he. The statesman smiled. “You take me out of my province

there,” said he.

Holmes considered for a moment. “There is another very

important point which I wish to discuss with you,” said he. “You feared, as I

understand, that very grave results might follow from the details of this treaty becoming

known.” Holmes considered for a moment. “There is another very

important point which I wish to discuss with you,” said he. “You feared, as I

understand, that very grave results might follow from the details of this treaty becoming

known.”

A shadow passed over the expressive face of the statesman.

“Very grave results indeed.” A shadow passed over the expressive face of the statesman.

“Very grave results indeed.”

“And have they occurred?” “And have they occurred?”

“Not yet.” “Not yet.”

“If the treaty had reached, let us say, the French or

Russian Foreign Office, you would expect to hear of it?” “If the treaty had reached, let us say, the French or

Russian Foreign Office, you would expect to hear of it?”

“I should,” said Lord Holdhurst with a wry face. “I should,” said Lord Holdhurst with a wry face.

“Since nearly ten weeks have elapsed, then, and nothing

has been heard, it is not unfair to suppose that for some reason the treaty has not

reached them.” “Since nearly ten weeks have elapsed, then, and nothing

has been heard, it is not unfair to suppose that for some reason the treaty has not

reached them.”

Lord Holdhurst shrugged his shoulders. Lord Holdhurst shrugged his shoulders.

“We can hardly suppose, Mr. Holmes, that the thief took

the treaty in order to frame it and hang it up.” “We can hardly suppose, Mr. Holmes, that the thief took

the treaty in order to frame it and hang it up.”

“Perhaps he is waiting for a better price.” “Perhaps he is waiting for a better price.”

“If he waits a little longer he will get no price at all.

The treaty will cease to be secret in a few months.” “If he waits a little longer he will get no price at all.

The treaty will cease to be secret in a few months.”

“That is most important,” said Holmes. “Of

course, it is a possible supposition that the thief has had a sudden illness–

–” “That is most important,” said Holmes. “Of

course, it is a possible supposition that the thief has had a sudden illness–

–”

“An attack of brain-fever, for example?” asked the

statesman, flashing a swift glance at him. “An attack of brain-fever, for example?” asked the

statesman, flashing a swift glance at him.

“I did not say so,” said Holmes imperturbably.

“And now, Lord Holdhurst, we have already taken up too much of your valuable time,

and we shall wish you good-day.” “I did not say so,” said Holmes imperturbably.

“And now, Lord Holdhurst, we have already taken up too much of your valuable time,

and we shall wish you good-day.”

“Every success to your investigation, be the criminal who

it may,” answered the nobleman as he bowed us out at the door. “Every success to your investigation, be the criminal who

it may,” answered the nobleman as he bowed us out at the door.

“He’s a fine fellow,” said Holmes as we came

out into Whitehall. “But he has a struggle to keep up his position. He is far from

rich and has many calls. You noticed, of course, that his boots had been resoled. Now,

Watson, I won’t detain you from your legitimate work any longer. I shall do nothing

more to-day unless I have an answer to my cab advertisement. But I should be extremely

obliged to you if you would come down with me to Woking to-morrow by the same train which

we took yesterday.” “He’s a fine fellow,” said Holmes as we came

out into Whitehall. “But he has a struggle to keep up his position. He is far from

rich and has many calls. You noticed, of course, that his boots had been resoled. Now,

Watson, I won’t detain you from your legitimate work any longer. I shall do nothing

more to-day unless I have an answer to my cab advertisement. But I should be extremely

obliged to you if you would come down with me to Woking to-morrow by the same train which

we took yesterday.”

I met him accordingly next morning and we travelled down to

Woking together. He had had no answer to his advertisement, he said, and no fresh light

had been thrown upon the case. He had, when he so willed it, the utter immobility of

countenance of a red Indian, and I could not gather from his appearance whether he was

satisfied or not with the position of the case. His conversation, I remember, was about

the Bertillon system of measurements, and he expressed his enthusiastic admiration of the

French savant. I met him accordingly next morning and we travelled down to

Woking together. He had had no answer to his advertisement, he said, and no fresh light

had been thrown upon the case. He had, when he so willed it, the utter immobility of

countenance of a red Indian, and I could not gather from his appearance whether he was

satisfied or not with the position of the case. His conversation, I remember, was about

the Bertillon system of measurements, and he expressed his enthusiastic admiration of the

French savant.

We found our client still under the charge of his devoted

nurse, but looking [461] considerably

better than before. He rose from the sofa and greeted us without difficulty when we

entered. We found our client still under the charge of his devoted

nurse, but looking [461] considerably

better than before. He rose from the sofa and greeted us without difficulty when we

entered.

“Any news?” he asked eagerly. “Any news?” he asked eagerly.

“My report, as I expected, is a negative one,” said

Holmes. “I have seen Forbes, and I have seen your uncle, and I have set one or two

trains of inquiry upon foot which may lead to something.” “My report, as I expected, is a negative one,” said

Holmes. “I have seen Forbes, and I have seen your uncle, and I have set one or two

trains of inquiry upon foot which may lead to something.”

“You have not lost heart, then?” “You have not lost heart, then?”

“By no means.” “By no means.”

“God bless you for saying that!” cried Miss

Harrison. “If we keep our courage and our patience the truth must come out.” “God bless you for saying that!” cried Miss

Harrison. “If we keep our courage and our patience the truth must come out.”

“We have more to tell you than you have for us,”

said Phelps, reseating himself upon the couch. “We have more to tell you than you have for us,”

said Phelps, reseating himself upon the couch.

“I hoped you might have something.” “I hoped you might have something.”

“Yes, we have had an adventure during the night, and one

which might have proved to be a serious one.” His expression grew very grave as he

spoke, and a look of something akin to fear sprang up in his eyes. “Do you

know,” said he, “that I begin to believe that I am the unconscious centre of

some monstrous conspiracy, and that my life is aimed at as well as my honour?” “Yes, we have had an adventure during the night, and one

which might have proved to be a serious one.” His expression grew very grave as he

spoke, and a look of something akin to fear sprang up in his eyes. “Do you

know,” said he, “that I begin to believe that I am the unconscious centre of

some monstrous conspiracy, and that my life is aimed at as well as my honour?”

“Ah!” cried Holmes. “Ah!” cried Holmes.

“It sounds incredible, for I have not, as far as I know,

an enemy in the world. Yet from last night’s experience I can come to no other

conclusion.” “It sounds incredible, for I have not, as far as I know,

an enemy in the world. Yet from last night’s experience I can come to no other

conclusion.”

“Pray let me hear it.” “Pray let me hear it.”

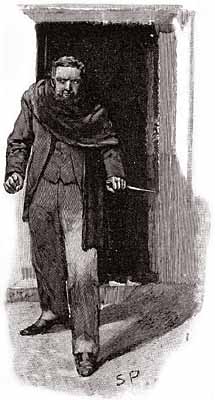

“You must know that last night was the very first night

that I have ever slept without a nurse in the room. I was so much better that I though I

could dispense with one. I had a night-light burning, however. Well, about two in the

morning I had sunk into a light sleep when I was suddenly aroused by a slight noise. It

was like the sound which a mouse makes when it is gnawing a plank, and I lay listening to

it for some time under the impression that it must come from that cause. Then it grew

louder, and suddenly there came from the window a sharp metallic snick. I sat up in

amazement. There could be no doubt what the sounds were now. The first ones had been

caused by someone forcing an instrument through the slit between the sashes, and the

second by the catch being pressed back. “You must know that last night was the very first night

that I have ever slept without a nurse in the room. I was so much better that I though I

could dispense with one. I had a night-light burning, however. Well, about two in the

morning I had sunk into a light sleep when I was suddenly aroused by a slight noise. It

was like the sound which a mouse makes when it is gnawing a plank, and I lay listening to

it for some time under the impression that it must come from that cause. Then it grew

louder, and suddenly there came from the window a sharp metallic snick. I sat up in

amazement. There could be no doubt what the sounds were now. The first ones had been

caused by someone forcing an instrument through the slit between the sashes, and the

second by the catch being pressed back.

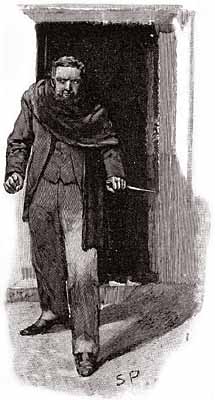

“There was a pause then for about ten minutes, as if the

person were waiting to see whether the noise had awakened me. Then I heard a gentle

creaking as the window was very slowly opened. I could stand it no longer, for my nerves

are not what they used to be. I sprang out of bed and flung open the shutters. A man was

crouching at the window. I could see little of him, for he was gone like a flash. He was

wrapped in some sort of cloak which came across the lower part of his face. One thing only

I am sure of, and that is that he had some weapon in his hand. It looked to me like a long

knife. I distinctly saw the gleam of it as he turned to run.” “There was a pause then for about ten minutes, as if the

person were waiting to see whether the noise had awakened me. Then I heard a gentle

creaking as the window was very slowly opened. I could stand it no longer, for my nerves

are not what they used to be. I sprang out of bed and flung open the shutters. A man was

crouching at the window. I could see little of him, for he was gone like a flash. He was

wrapped in some sort of cloak which came across the lower part of his face. One thing only

I am sure of, and that is that he had some weapon in his hand. It looked to me like a long

knife. I distinctly saw the gleam of it as he turned to run.”

“This is most interesting,” said Holmes. “Pray

what did you do then?” “This is most interesting,” said Holmes. “Pray

what did you do then?”

“I should have followed him through the open window if I

had been stronger. As it was, I rang the bell and roused the house. It took some little

time, for the bell rings in the kitchen and the servants all sleep upstairs. I shouted,

however, and that brought Joseph down, and he roused the others. Joseph and the groom

found marks on the bed outside the window, but the weather has been so dry lately that

they found it hopeless to follow the trail across the grass. There’s a place,

however, on the wooden fence which skirts the road which shows signs, [462] they tell me, as if someone

had got over, and had snapped the top of the rail in doing so. I have said nothing to the

local police yet, for I thought I had best have your opinion first.” “I should have followed him through the open window if I

had been stronger. As it was, I rang the bell and roused the house. It took some little

time, for the bell rings in the kitchen and the servants all sleep upstairs. I shouted,

however, and that brought Joseph down, and he roused the others. Joseph and the groom

found marks on the bed outside the window, but the weather has been so dry lately that

they found it hopeless to follow the trail across the grass. There’s a place,

however, on the wooden fence which skirts the road which shows signs, [462] they tell me, as if someone

had got over, and had snapped the top of the rail in doing so. I have said nothing to the

local police yet, for I thought I had best have your opinion first.”

This tale of our client’s appeared to have an

extraordinary effect upon Sherlock Holmes. He rose from his chair and paced about the room

in uncontrollable excitement. This tale of our client’s appeared to have an

extraordinary effect upon Sherlock Holmes. He rose from his chair and paced about the room

in uncontrollable excitement.

“Misfortunes never come single,” said Phelps,

smiling, though it was evident that his adventure had somewhat shaken him. “Misfortunes never come single,” said Phelps,

smiling, though it was evident that his adventure had somewhat shaken him.

“You have certainly had your share,” said Holmes.

“Do you think you could walk round the house with me?” “You have certainly had your share,” said Holmes.

“Do you think you could walk round the house with me?”

“Oh, yes, I should like a little sunshine. Joseph will

come, too.” “Oh, yes, I should like a little sunshine. Joseph will

come, too.”

“And I also,” said Miss Harrison. “And I also,” said Miss Harrison.

“I am afraid not,” said Holmes, shaking his head.

“I think I must ask you to remain sitting exactly where you are.” “I am afraid not,” said Holmes, shaking his head.

“I think I must ask you to remain sitting exactly where you are.”

The young lady resumed her seat with an air of displeasure.

Her brother, however, had joined us and we set off all four together. We passed round the

lawn to the outside of the young diplomatist’s window. There were, as he had said,

marks upon the bed, but they were hopelessly blurred and vague. Holmes stooped over them

for an instant, and then rose shrugging his shoulders. The young lady resumed her seat with an air of displeasure.

Her brother, however, had joined us and we set off all four together. We passed round the

lawn to the outside of the young diplomatist’s window. There were, as he had said,

marks upon the bed, but they were hopelessly blurred and vague. Holmes stooped over them

for an instant, and then rose shrugging his shoulders.

“I don’t think anyone could make much of this,”

said he. “Let us go round the house and see why this particular room was chosen by

the burglar. I should have thought those larger windows of the drawing-room and

dining-room would have had more attractions for him.” “I don’t think anyone could make much of this,”

said he. “Let us go round the house and see why this particular room was chosen by

the burglar. I should have thought those larger windows of the drawing-room and

dining-room would have had more attractions for him.”

“They are more visible from the road,” suggested Mr.

Joseph Harrison. “They are more visible from the road,” suggested Mr.

Joseph Harrison.

“Ah, yes, of course. There is a door here which he might

have attempted. What is it for?” “Ah, yes, of course. There is a door here which he might

have attempted. What is it for?”

“It is the side entrance for trades-people. Of course it

is locked at night.” “It is the side entrance for trades-people. Of course it

is locked at night.”

“Have you ever had an alarm like this before?” “Have you ever had an alarm like this before?”

“Never,” said our client. “Never,” said our client.

“Do you keep plate in the house, or anything to attract

burglars?” “Do you keep plate in the house, or anything to attract

burglars?”

“Nothing of value.” “Nothing of value.”

Holmes strolled round the house with his hands in his pockets